Abstract

Background and Objectives

Inherited disorders of GABA metabolism include SSADH and GABA-transaminase deficiencies. The clinical features, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of both are discussed, including an updated list of ALDH5A1 mutations causing SSADH deficiency.

Methods

Our SSADH patient database was analyzed and murine and translational studies leading to clinical trials are reviewed.

Results

The database containing 112 SSADH-deficient patients (71 pediatric and adolescent subjects, 41 adults) indicates that developmental delay and hypotonia are the most common presenting symptoms. Epilepsy is present in 2/3 of patients by adulthood. Murine genetic model, and human studies using flumazenil-PET and transcranial magnetic stimulation, have led to therapeutic trials and identified additional metabolic disruptions. Suggestions for new therapies have arisen from findings of GABAergic effects on autophagy with enhanced activation of the mTor pathway. A total of 45 pathogenic mutations have been reported in SSADH deficiency including the discovery of three previously unreported.

Conclusions

Investigations into the disorders of GABA metabolism provide fundamental insights into mechanisms underlying epilepsy and support the development of biomarkers and clinical trials. Comprehensive definition of the phenotypes of both SSADH and GABA-T deficiencies may increase our knowledge of the neurophysiological consequences of a hyperGABAergic state.

Keywords: SSADH deficiency, GABA-transaminase deficiency, neurometabolic diseases, epileptic encephalopathy, seizures

The GABA metabolic pathway and its disruptions

After discovery by Roberts and Frankel in 1950,1 GABA was proposed to be an inhibitory neurotransmitter.2,3 GABA is in fact the brain’s major inhibitory neurotransmitter, with thirty to forty percent of cerebral synapses using it to facilitate inhibition. Only the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate is more prevalent in the central nervous system.

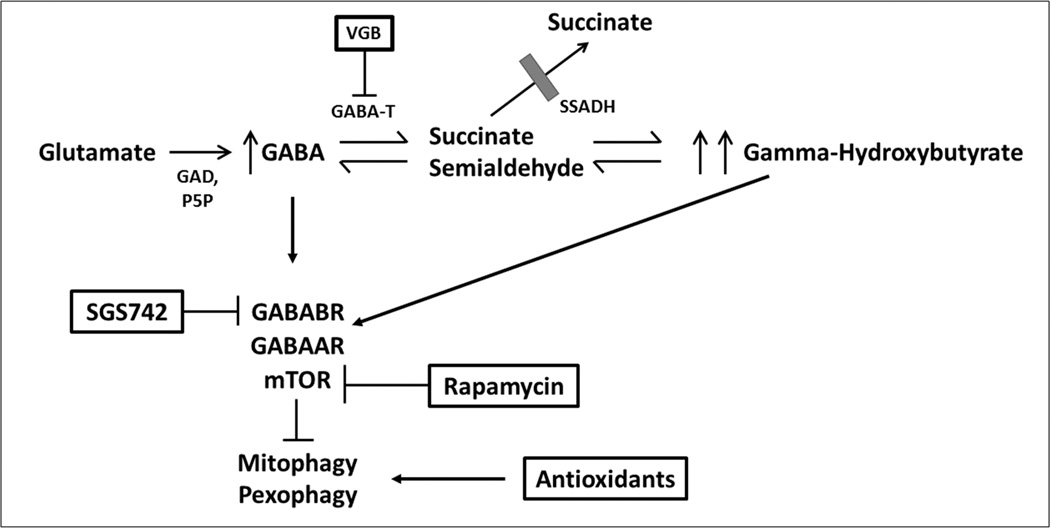

GABA results from a conversion of L-glutamate via glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) (Figure). Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) and GABA-transaminase (GABA-T) work in tandem to convert GABA to succinate. Specifically, GABA-T metabolizes GABA to succinic semialdehyde, which is rapidly metabolized to succinic acid and then enters the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Through the transamination of alpha-ketoglutarate, the closed loop of this process returns to glutamate and its conversion to GABA via GAD.

Figure.

The metabolic pathway of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and potential targets for therapeutic trials in SSADH deficiency.

GAD = glutamic acid decarboxylase

P5P = pyridoxal-5’-phosphate

VGB = vigabatrin

GABA-T = GABA-transaminase

SSADH = succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase

GABABR = GABAB receptor

GABAAR = GABAA receptor

mTOR = mammalian target of rapamycin

For the transamination of GABA to succinic semialdehyde, alpha-ketoglutarate must be present to accept the amine group, a process which restores glutamate. The neurotransmitter pool is constantly replenished as one mole of glutamate is produced for each mole of GABA that is converted to succinate4.

In a metabolite cycle known as the glutamine-glutamate shuttle, GABA is taken up by glial cells and converted to glutamine via glutamine synthetase in the absence of GAD. Glutamine is returned to the neuron and is then converted back to glutamate via glutaminase, ultimately recycling glutamate. This completes the loop and conserves the supply of GABA precursor.

The GABA metabolic pathway is disrupted by deficiencies in GABA-T and SSADH.5,6 This review will focus on deficiencies in SSADH and GABA-T, both of which are inherited as autosomal recessive disorders.

In brief, SSADH deficiency is a rare inborn neurometabolic disorder with clinical manifestations including developmental delay and early hypotonia, later expressive language impairment and obsessive-compulsive disorder, hyporeflexia, nonprogressive ataxia and epilepsy. The diagnosis is indicated by the accumulation of GABA and its metabolite, gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), in the absence of SSADH. SSADH deficiency has been identified in hundreds of patients worldwide and sequencing reveals homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations identified in the ALDH5A1 gene in nearly all families.

GABA-T deficiency is associated with neonatal seizures, profound developmental impairment, and growth acceleration. The diagnosis requires CSF analysis of GABA concentrations. GABA-T deficiency has been confirmed in two unrelated patients and suspected in an older sibling of one of these patients, who died at the age of 1 year with a clinical picture similar to that of his affected sibling.

Biochemical characteristics

The mitochondrial protein, succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) is in the aldehyde dehydrogenase family (subfamily 5A1). SSADH locates to the ALDH5A1 gene at chromosome 6p22.3 and produces succinic acid. The mitochondrial protein, 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase (GABA-T) locates to the ABAT gene at chromosome 16p13.2. The product of GABA-T is succinic semialdehyde.

Pathophysiology of SSADH and GABA-T deficiencies

Gibson and colleagues7 created a mouse model of SSADH deficiency via gene targeting in which the aldh5a1−/− mouse developed fatal status epilepticus and died between postnatal days 20–26. The development of this murine model has facilitated numerous opportunities for researchers to reconsider the pathophysiology of general inborn metabolic disorders and SSADH deficiency in particular.8

The murine model demonstrates a progression from initial absence seizures to tonicclonic convulsions to lethal status epilepticus.9–12 Both transcranial magnetic stimulation and flumazenil-PET studies have evinced GABA-dependent down-regulation of GABAA and GABAB receptors in animal studies as well as patients.13,14 Due to the high content of the sulfonated amino acid, taurine, in dam’s milk and knowledge of lethal status epilepticus occurrence during the weaning period of newborn mice, taurine was studied and shown to significantly extend lifespan in affected mice. Also extending lifespan were the GABAB receptor antagonist CGP-35348, vigabatrin, and the high-affinity GHB receptor antagonist NCS-382,15,16 as well as a 4:1 ketogenic diet.17 Maximal life extension for aldh5a1−/− mice was provided by the GHB receptor antagonist NCS-382, suggesting for a role of GHB in the pathophysiology. Mehta and colleagues,18 however, did not find alterations in number of GHB receptors, binding affinity and expression in aldh5a1−/− brain sections. Study limitations included the possibilities that reduced lifespan prohibited GHB receptor down-regulation, the use of only a single pH for binding studies, the lack of specificity of the ligand (NCS-382), and that down-regulation of GHB receptors may have been transient. However, high-dose GHB, as found in SSADH-deficient brains, activates a specific subset of GABAB receptors,19 and recent studies on recombinant GABAA receptors indicate GHB activates a specific GABAA subset of receptors as well.20

Other metabolites accumulate in addition to GABA and GHB, including 4,5-dihydroxyhexanoic acid and homocarnosine; furthermore, glutamine homeostasis is disrupted based on evidence from the animal model.22,23 Recent studies indicate GABA-mediated activation of the mTOR pathway, as shown by increased mitochondria in the mutant mouse, associated with increased biomarkers of oxidative stress.4 This suggests a potential role for the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin as well as antioxidant therapy in this disorder. Vigabatrin, an irreversible inhibitor of GABA transaminase, will reduce GHB levels as shown in CSF of treated patients.21 Thus, combination therapy, for example of vigabatrin and rapamycin, are in development in phase 1 animal studies.

In deficiency of the enzyme GABA-transaminase, CSF GABA levels have been reported as 16–60 times elevated.24,25 The finding of growth acceleration in GABA-T deficiency may be related to the effect of GABA on the release of growth hormone.26

METHODS

Our SSADH patient database was analyzed and murine and translational studies leading to clinical trials are reviewed. All previously reported mutations associated with pathogenicity in SSADH deficiency were reviewed and previously unreported mutations identified within our database are presented. This study was approved by the Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board (protocol 3660).

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics

SSADH deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder identified in several hundred patients.6,27–29 Onset of symptoms occurs at a mean age of 11 months (range 0–44 months).30 The disease usually has a nonprogressive course and is difficult to distinguish from static encephalopathy, although early-onset cases may have a more severe course, with extrapyramidal signs and death in infancy, and some patients show regression.31

Typical clinical manifestations are hypotonia, developmental delay, ataxia, and hyporeflexia. Nearly all patients present with hypotonia and developmental delay. The ataxia is nonprogressive and tends to improve with time. Hyporeflexia is noted on most patients on the neurological examination. Cognitive impairment is typical and expressive language deficits are prominent.33 In about half of patients, epilepsy usually occurs as generalized tonic-clonic seizures, although absence and myoclonic seizures occur.29 Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) has been reported.43 Additionally, extrapyramidal signs may be present, including dystonia, myoclonus, and choreoathetosis.

Neuropsychiatric problems tend to be the most problematic for quality of life and are marked by inattention and aggression in early childhood, and disabling obsessive-compulsive disorder in adolescence and beyond.34,35 The most common sleep disturbance is insomnia, and overnight sleep studies show decreased stage REM percentage and prolonged latency to stage REM, with decreased mean sleep latency on daytime studies consistent with excessive daytime somnolence.36–38

GABA-T deficiency has been detected in one index sibship and one additional patient from an unrelated family.32 Other cases may be undetected because of the general lack of testing for CSF GABA quantification. The phenotype is that of a severe neonatal or infantile epileptic encephalopathy. Clinical features reported have been neonatal seizures, lethargy, hypotonia, hyperreflexia, poor feeding, and rapid cranial growth acceleration, as well as myoclonic seizures in infancy. Neuroimaging showed severe enlargement of CSF containing spaces, and neuropathology of the index patient’s sibling showing spongiform white matter changes with decreased myelination.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of SSADH deficiency should be taken into consideration if cases present with slowly progressive or static encephalopathy and late-infantile to early-childhood onset with the primary clinical features noted above, especially the motor and language delays.

Urine organic acid analysis, specifically gas chromatography mass spectrometry, produces the most reliable laboratory test findings. The presence of persistent GHB on urine organic acid analysis [100–1200 mmol/mol creatine (normal, 0–7 mmol/mol creatinine)] is consistent with a diagnosis of SSADH deficiency. In patients whose neuropsychiatric disturbances or developmental delays are of unknown etiology, urine organic acid analysis should be considered with specific attention to the presence of 4-OH-butyric acid.

EEG studies, while nonspecific, indicate background slowing and semirhythmic to rhythmic spike-and-wave paroxysms seen diffusely that may have asynchrony or variable hemispheric dominance.37 Photosensitivity and electrographic status epilepticus of slow wave sleep have been rarely recorded.

Brain MRI shows a characteristic pattern of hyperintensity of the globus pallidus, cerebellar dentate nucleus, and subthalamic nucleus. These lesions are typically, but not always, bilateral and symmetrical. Additional imaging findings are hyperintensities in subcortical white matter and brain stem, including substantia nigra, and cerebral hemispheric and cerebellar atrophy. Brain MRS shows increased endogenous GABA in brain parenchyma.58

A diagnosis of SSADH deficiency may be confirmed by enzymatic quantification, although is now done by most laboratories as sequencing, or if indicated deletion/duplication testing, of the ALDH5A1 gene. Sequence analysis identifies pathogenic variants in the majority of families.40 Table 1 lists published mutations associated with causation of the condition as well as new mutations being reported in this manuscript.

Table.

Summary of Disease-Associated Mutations in ALDH5A1 (SSADH Deficiency)

| Exon | Nucleotide change |

Change in protein |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | c.34dupG | p.a12fsX123 | 39 |

| 1 | c.103_121del | p.S35fsX49 | 51 |

| 1 | c.160_161delCT | p.S55fsX79 | 39 |

| 1 | c.235C>T | p.Q79X | 39 |

| 1 | c.278G>T | p.C93F | 39 |

| 1 | c.278_298dup | p.C93_R99dup | 39 |

| 1 | c.384C>G | p.Y128X | 39 |

| 1 | c.412C>T | p.L138F | * |

| 1 | c.455_456dupAG | p.A153fsX12 | 39 |

| 1 | c.460_473del | p.H154fsX10 | 39 |

| 1 | c.466G>A | p.E156K | 56 |

| Exon 2 / Exon 5 |

r.EX2_EX5del | p.E119_K290del | 39 |

| 2 | c.517C>T | p.R173C | 56 |

| 2 | c.526G>A | p.G176R | 39 |

| 2 | c.527G>A | p.N176S | 53 |

| 2 | c.574A>T | p.K192X | 39 |

| 3 | c.587G>A | p.G196D | 55 |

| Intron 3 / Exon 4 |

IVS3—2 A>G (r.439_452del) |

p.K148fsX16 | 39 |

| 3 | c.612G>A | p.W204X | 39 |

| 3 | c.621delC | p.S208fsX2 | 39, 46 |

| 3 | c.608C>T | p.P203L | 57 |

| 3 | c.668G>A | p.C223Y | 39 |

| 3 | c.691G>A | p.N231D | 53 |

| 3 | c.698C>T | p.T233M | 39 |

| 4 | c.754G>T | p.Q252X | * |

| 4 | c.764A>G | p.N255S | 39 |

| 4 | c.781C>T | p.R261X | 39 |

| 5 | c.803G>A | p.G268E | 39 |

| Exon 5 / Intron 5 |

IVS5+1G>A (r.EX5del) |

p.L243_K290del | 39 |

| Exon 5 / Intron 5 |

IVS5+1G>T (r.EX5del) |

p.L243_K290del | 39 |

| 5 | c.901A>G | p.K301E | 52 |

| 5 | c.1005C>A | p.N335K | 39 |

| 6 | c.1145C>T | p.P382L | 39 |

| 6 | c.1145C>A | p.382Q | 39 |

| 7 | c.1226G>A | p.G409D | 39, 54 |

| 7 | c.1234C>T | p.R412X | 39 |

| 8 | c.1323dupG | p.P442fsX18 | 39 |

| Exon 8 / Intron 8 |

IVS8+1delG; IVS8+3A>T (rEX8del) |

p.V392fsX10 | 39 |

| Exon 9 / Intron 9 |

IVS9+1G>T (r.EX9del) |

p.F449fsX53 | 39 |

| 8 | c.1333A>C | p.M445L | 60 |

| 8 | c.1360G>A | p.A454T | * |

| 8 | c.1460T>A | p.V487E | 51 |

| 9 | c.1540C>T | p.R514X | 39 |

| 10 | c.1557T>G | p.Y519X | 45 |

| 10 | c.1597G>A | p.G533R | 39 |

(* previously unpublished)

Diagnosis of GABA-T deficiency relies on a high index of suspicion and detecting elevated amino acids in CSF, specifically GABA and beta-alanine although not GHB. MR spectroscopy for elevated GABA using voxels of the basal ganglia has been used to identify the diagnosis. Both patients confirmed were compound heterozygotes. The index patient had an A-to-G transition at a highly conserved site, affecting binding of the cofactor pyridoxal-5-phosphate, which is required for the transamination of GABA to succinic semialdehyde. The second allele was a T-to-C transition causing a substitution of leucine to proline. The unrelated patient had a missense mutation and a deletion of the GABA-transaminase coding region.26

Other diagnostic issues

Prenatal diagnosis is made possible through amniocentesis for measurement of amniotic fluid GHB for SSADH deficiency, or of GABA and beta-alanine for GABA-T deficiency, or chorionic villus tissue and cultured amniocytes for metabolite measurements or gene testing. The technical feasibility of dried blood spot testing for GHB, applicable to newborn screening for SSADH deficiency, was demonstrated by Forni et al.41 Late diagnosis, however, remains problematic as the non-specific clinical phenotype has caused adult patients to be improperly diagnosed or undiagnosed for decades.42

Long-term outlook

SSADH deficiency in adults causes disabling problems with obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety. SSADH-deficient adults in general require supervised living arrangements. Our database of 112 patients presenting with SSADH deficiency includes 41 adults age 18 years and older of which 27 (66%) have epilepsy, usually accompanied by generalized convulsive and nonconvulsive seizures.42 Reports have been made of sudden unexpected death (SUDEP),43 and progressive worsening with accelerating convulsive seizures and dementia in patients up to 63 years of age.61 Additional frequent reports of neuropsychiatric complications and sleep disturbances also persist, as well as notable anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder in adolescence and adulthood.

In GABA-T deficiency, both index family patients died at 1 and 2 years of age. The unrelated patient was alive at 28 months of age, the time of the report.

ALDH5A1 MUTATIONS

Pathogenic mutations in the ALDH5A1 gene (SSADH deficiency), including three previously unreported mutations from our database, are listed in the following table:

DISCUSSION

Neurotoxicity and implications in development

Although the exact mechanisms of GHB neurotoxicity in humans is still a topic of study, the neurotoxic effects of elevated endogenous GHB concentrations have shown to significantly increase various parameters of oxidative stress in recent murine studies. It is postulated that GHB neurotoxicity causes accumulation of lipid peroxidative byproducts (thiobarbituric acid reactive substances) and significantly diminishes antioxidant reactivity, thereby exacerbating neurodegeneration in patients presenting with SSADH deficiency. Excessively damaged mitochondria will induce the cell to undergo apoptosis as markedly high GHB levels in the central nervous system (CNS) likely have the capacity of causing oxidative stress. It is, however, uncertain whether this oxidative stress is a primary contributor to the onset of neurodegeneration or if its manifestation is secondary in the neurodegenerative process of SSADHD.59

It has been noted that not all SSADH-deficient patients exhibit the same response to a single potential therapeutic. The inconsistency in effectiveness of therapeutics for SSADH-deficient patients, but heterogeneity of clinical manifestations, may be due to variances in the developmental onset of circuit aberrations in SSADH deficient patients. Prior to undertaking its role as the key inhibitory neurotransmitter in mature neuronal networks, GABA is excitatory in the developing brain due to high intracellular chloride concentrations. Chronically elevated cerebral GABA and GHB concentrations during the crucial developmental stages may have different effects on neurotransmission.13

Treatment

There are no specific pharmacological strategies to address the metabolic defects. Thus, therapy is targeted, especially in terms of antiepileptic agents. Characterization of epilepsy as seen in SSADH-deficient patients guides antiepileptic drug therapy to agents used for generalized seizures. Valproate is not used first-line due to inhibition of any residual enzymatic activity,47 although magnesium valproate treatment controlled refractory epilepsy in a single SSADH-deficient patient, associated with improved behavior and EEG findings.48 Patients have shown reasonable seizure control with lamotrigine and carbamazepine. Results have been inconsistent with vigabatrin.44,45 Vigabatrin has been associated with a demonstrable decrease in CSF GHB concentration in occasional case reports.62 Taurine was associated with developmental improvement in a two-year-old boy in an anecdotal report57, while an open label clinical trial did not yield significant improvements in adaptive behavioral functioning.49

Novel directions

Studies of SSADH and reports of GABA-T deficiencies have engendered new discernments into GABA-related biology, expanding our understanding of GABA beyond its role as an inhibitory neurotransmitter. They also provide opportunities to rethink fundamental questions encompassing epileptic mechanisms.4 The rarity of GABA-transaminase deficiency suggests the mutation may be lethal in utero or that the phenotype is far from defined, with lack of CSF GABA determination being a major diagnostic obstacle.

The SSADH murine knockout model has informed us of the neurophysiological consequences of a hyperGABAergic state, accumulation of GABA, GHB, and related metabolites and disruption of the glial-neuronal glutamine shuttle. Overuse dependent downregulation of both GABA(A) and (B) receptors has been demonstrated in the animal model, and then replicated in affected patients whereas flumazenil-PET showed decreased GABA(A) receptor binding,50 and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) indicated reduction of the cortical silent period and long interval intracortical inhibition consistent with GABA(B) receptor underactivity.33 This work has led to clinical trials, from taurine intervention to a currently enrolling trial of the GABAB receptor antagonist, SGS-742 (www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT01608178; NCT02019667). Implementation of a combination of interventions may be necessary to address the complex clinical representation and offer maximum benefit.

What this paper adds.

Translational studies from a murine knockout model confirm overuse dependent downregulation of GABAA and GABAB receptors in patients.

Biomarker development during translational trials has enabled a pathway to clinical trials now in progress for subjects with SSADH deficiency.

An updated comprehensive table of published mutations identified in ALDH5A1 including three previously unreported.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Shaye Moore and Elizabeth Jarvis for their technical assistance. Grant/research support from NIH/NINDS: NCT02019667.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roberts E, Frankel S. gamma-Aminobutyric acid in brain: its formation from glutamic acid. J Biol Chem. 1950 Nov;187(1):55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtis DR, Watkins JC. The excitation and depression of spinal neurones by structurally related amino acids. J Neurochem. 1960 Sep;6:117–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1960.tb13458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krnjevic K, Schwartz S. The action of gamma-aminobutyric acid on cortical neurones. Exp Brain Res. 1967;3(4):320–336. doi: 10.1007/BF00237558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lakhani R, Vogel KR, Till A, Liu J, Burnett SF, Gibson KM, et al. Defects in GABA metabolism affect selective autophagy pathways and are alleviated by mTOR inhibition. EMBO Mol Med. 2014 Apr 1;6(4):551–566. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201303356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson KM, Nyhan WL, Jaeken J. Inborn errors of GABA metabolism. Bioessays. 1986 Jan;4(1):24–27. doi: 10.1002/bies.950040107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson KM, Jakobs C. Disorders of beta- and alpha-amino acids in free and peptide-linked forms. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Childs B, Kinzler KW, et al., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8th ed. New York NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 2079–2105. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson KM, Jakobs C, Pearl PL, Snead OC. Murine succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) deficiency, a heritable disorder of GABA metabolism with epileptic phenotype. IUBMB Life. 2005 Sep;57(9):639–644. doi: 10.1080/15216540500264588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KJ, Pearl PL, Jensen K, Snead OC, Malaspina P, Jakobs C, et al. Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase: biochemical-molecular-clinical disease mechanisms, redox regulation, and functional significance. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011 Aug 1;15(3):691–718. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortez MA, Wu Y, Gibson KM, Snead OC., 3rd Absence seizures in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficient mice: a model of juvenile absence epilepsy. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004 Nov;79(3):547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buzzi A, Wu Y, Frantseva MV, Perez Velazquez JL, Cortez MA, Liu CC, et al. Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency: GABAB receptor-mediated function. Brain Res. 2006 May 23;1090(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Buzzi A, Frantseva M, Velazquez JP, Cortez M, Liu C, et al. Status epilepticus in mice deficient for succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase: GABAA receptor-mediated mechanisms. Ann Neurol. 2006 Jan;59(1):42–52. doi: 10.1002/ana.20686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogel KR, Pearl PL, Theodore WH, McCarter RC, Jakobs C, Gibson KM. Thirty years beyond discovery--clinical trials in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency, a disorder of GABA metabolism. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013 May;36(3):401–410. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9499-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reis J, Cohen LG, Pearl PL, Fritsch B, Jung NH, Dustin I, et al. GABAB-ergic motor cortex dysfunction in SSADH deficiency. Neurology. 2012 Jul 3;79(1):47–54. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825dcf71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearl PL, Gibson KM, Quezado Z, Dustin I, Taylor J, Trzcinski S, et al. Decreased GABA-A binding on FMZ-PET in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency. Neurology. 2009 Aug 11;73(6):423–429. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b163a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogema BM, Akaboshi S, Taylor M, Salomons GS, Jakobs C, Schutgens RB, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency: increased accuracy employing DNA, enzyme, and metabolite analyses. Mol Genet Metab. 2001 Mar;72(3):218–222. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta M, Greven R, Jansen EE, Jakobs C, Hogema BM, Froestl W, et al. Therapeutic intervention in mice deficient for succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (gamma-hydroxybutyric aciduria) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002 Jul;302(1):180–187. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nylen K, Velazquez JL, Likhodii SS, Cortez MA, Shen L, Leshchenko Y, et al. A ketogenic diet rescues the murine succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficient phenotype. Exp Neurol. 2008 Apr;210(2):449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta AK, Gould GG, Gupta M, Carter LP, Gibson KM, Ticku MK. Succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency does not down-regulate gamma-hydroxybutyric acid binding sites in the mouse brain. Mol Genet Metab. 2006 May;88(1):86–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bay T, Eghorn LF, Klein AB, Wellendorph P. GHB receptor targets in the CNS: focus on high-affinity binding sites. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014 Jan 15;87(2):220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Absalom N, Eghorn LF, Villumsen IS, Karim N, Bay T, Olsen JV, Knudsen GM, Brauner-Osborne H, Frolund B, Clausen RP, Chebib M, Wellendorph P. GABA(A) receptors are high-affinity targets for gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2012;109(33):13404–13409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204376109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson KM. Gamma-hydroxybutyric aciduria: a biochemist's education from a heritable disorder of GABA metabolism. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28(3):247–265. doi: 10.1007/s10545-005-7053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sgaravatti AM, Sgarbi MB, Testa CG, Durigon K, Pederzolli CD, Prestes CC, et al. Gamma-hydroxybutyric acid induces oxidative stress in cerebral cortex of young rats. Neurochem Int. 2007 Feb;50(3):564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latini A, Scussiato K, Leipnitz G, Gibson KM, Wajner M. Evidence for oxidative stress in tissues derived from succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase-deficient mice. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007 Oct;30(5):800–810. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0599-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakobs C, Jaeken J, Gibson KM. Inherited disorders of GABA metabolism. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1993;16(4):704–715. doi: 10.1007/BF00711902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuji M, Aida N, Obata T, Tomiyasu M, Furuya N, Kurosawa K, et al. A new case of GABA transaminase deficiency facilitated by proton MR spectroscopy. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010 Feb;33(1):85–90. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-9022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaeken J, Casaer P, Haegele KD, Schechter PJ. Review: Normal and abnormal central nervous system GABA metabolism in childhood. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1990;13(6):793–801. doi: 10.1007/BF01800202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jakobs C, Bojasch M, Monch E, Rating D, Siemes H, Hanefeld F. Urinary excretion of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid in a patient with neurological abnormalities. The probability of a new inborn error of metabolism. Clin Chim Acta. 1981 Apr 9;111(2–3):169–178. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(81)90184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibson KM, Christensen E, Jakobs C, Fowler B, Clarke MA, Hammersen G, et al. The clinical phenotype of succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency (4-hydroxybutyric aciduria): case reports of 23 new patients. Pediatrics. 1997 Apr;99(4):567–574. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearl PL, Gibson KM, Acosta MT, Vezina LG, Theodore WH, Rogawski MA, et al. Clinical spectrum of succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency. Neurology. 2003 May 13;60(9):1413–1417. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000059549.70717.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearl PL, Gibson KM, Cortez MA, Wu Y, Carter Snead O, 3rd, Knerr I, et al. Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency: lessons from mice and men. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009 Jun;32(3):343–352. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-1034-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearl PL, Acosta MT, Wallis DD, Bottiglieri T, Miotto K, Jakobs C, et al. Dyskinetic features of succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency, a GABA degradative defect. In: Fernandez-Alvarez E, Arzimanoglou A, Tolosa E, editors. Paediatric Movement Disorders: Progress in Understanding. Surrey UK: John Libbey Eurotext; 2005. pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medina-Kauwe LK, Tobin AJ, De Meirleir L, Jaeken J, Jakobs C, Nyhan WL, et al. 4-Aminobutyrate aminotransferase (GABA-transaminase) deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1999 Jun;22(4):414–427. doi: 10.1023/a:1005500122231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearl PL, Capp PK, Novotny EJ, Gibson KM. Inherited disorders of neurotransmitters in children and adults. Clin Biochem. 2005 Dec;38(12):1051–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearl PL, Gibson KM. Clinical aspects of the disorders of GABA metabolism in children. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004 Apr;17(2):107–113. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knerr I, Gibson KM, Jakobs C, Pearl PL. Neuropsychiatric morbidity in adolescent and adult succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency patients. CNS Spectr. 2008 Jul;13(7):598–605. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900016874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Philippe A, Deron J, Genevieve D, de Lonlay P, Gibson KM, Rabier D, et al. Neurodevelopmental pattern of succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency (gamma-hydroxybutyric aciduria) Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004 Aug;46(8):564–568. doi: 10.1017/s0012162204000933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnulf I, Konofal E, Gibson KM, Rabier D, Beauvais P, Derenne JP, et al. Effect of genetically caused excess of brain gamma-hydroxybutyric acid and GABA on sleep. Sleep. 2005 Apr;28(4):418–424. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearl PL, Shamim S, Theodore WH, Gibson KM, Forester K, Combs SE, et al. Polysomnographic abnormalities in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) deficiency. Sleep. 2009 Dec;32(12):1645–1648. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.12.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janssen AJ, Schuelke M, Smeitink JA, Trijbels FJ, Sengers RC, Lucke B, et al. Muscle 3243A-->G mutation load and capacity of the mitochondrial energy-generating system. Ann Neurol. 2008 Apr;63(4):473–481. doi: 10.1002/ana.21328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akaboshi S, Hogema BM, Novelletto A, Malaspina P, Salomons GS, Maropoulos GD, et al. Mutational spectrum of the succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH5A1) gene and functional analysis of 27 novel disease-causing mutations in patients with SSADH deficiency. Hum Mutat. 2003 Dec;22(6):442–450. doi: 10.1002/humu.10288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forni S, Pearl PL, Gibson KM, Yu Y, Sweetman L. Quantitation of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid in dried blood spots: feasibility assessment for newborn screening of succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2013 Jul;109(3):255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parviz M, Vogel K, Gibson KM, Pearl PL. Disorders of GABA Metabolism: SSADH and GABA-transaminase Deficiencies. J Pediatr Epilepsy. 2014 Oct;3(3) doi: 10.3233/PEP-14097. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knerr I, Gibson KM, Murdoch G, Salomons GS, Jakobs C, Combs S, et al. Neuropathology in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency. Pediatr Neurol. 2010 Apr;42(4):255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matern D, Lehnert W, Gibson KM, Korinthenberg R. Seizures in a boy with succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency treated with vigabatrin (gamma-vinyl-GABA) J Inherit Metab Dis. 1996;19(3):313–318. doi: 10.1007/BF01799261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gropman A. Vigabatrin and newer interventions in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency. Ann Neurol. 2003;54(Suppl 6):S66–S72. doi: 10.1002/ana.10626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Casarano M, Alessandri MG, Salomons GS, Moretti E, Jakobs C, Gibson KM, et al. Efficacy of vigabatrin intervention in a mild phenotypic expression of succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency. JIMD Rep. 2012;2:119–123. doi: 10.1007/8904_2011_60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shinka T, Ohfu M, Hirose S, Kuhara T. Effect of valproic acid on the urinary metabolic profile of a patient with succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2003 Jul 15;792(1):99–106. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(03)00276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vanadia E, Gibson KM, Pearl PL, Trapolino E, Mangano S, Vanadia F. Therapeutic efficacy of magnesium valproate in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency. JIMD Rep. 2013;8:133–137. doi: 10.1007/8904_2012_170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pearl PL, Schreiber J, Theodore WH, McCarter R, Barrios ES, Yu J, et al. Taurine trial in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency and elevated CNS GABA. Neurology. 2014 Mar 18;82(11):940–944. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearl PL, Taylor JL, Trzcinski S, Sokohl A, Dustin I, Reeves-Tyer P, et al. 11C-Flumazenil PET imaging in patients with SSADH deficiency (Abstract) J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30(Suppl 1):43. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim YG, Lee S, Kwon OS, Park SY, Lee SJ, Park BJ, et al. Redox-switch modulation of human SSADH by dynamic catalytic loop. Embo J. 2009 Apr 8;28(7):959–968. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aoshima T, Kajita M, Sekido Y, Ishiguro Y, Tsuge I, Kimura M, et al. Mutation analysis in a patient with succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency: a compound heterozygote with 103–121del and 1460T >A of the ALDH5A1 gene. Hum Hered. 2002;53(1):42–44. doi: 10.1159/000048603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Puttmann L, Stehr H, Garshasbi M, Hu H, Kahrizi K, Lipkowitz B, et al. A novel ALDH5A1 mutation is associated with succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency and severe intellectual disability in an Iranian family. Am J Med Genet A. 2013 Aug;161A(8):1915–1922. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang SZ, Shu JB, Zhang YQ, Fan WX, Meng YT, Song L. [Analysis of ALDH5A1 gene mutation in a Chinese Han family with succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency] Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2013 Aug;30(4):389–393. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lemes A, Blasi P, Gonzales G, Russi ME, Quadrelli R, Novelletto A, et al. Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) deficiency: Molecular analysis in a South American family. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006 Aug;29(4):587. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jung R, Rauch A, Salomons GS, Verhoeven NM, Jakobs C, Michael Gibson K, et al. Clinical, cytogenetic and molecular characterization of a patient with combined succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency and incomplete WAGR syndrome with obesity. Mol Genet Metab. 2006 Jul;88(3):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saronwala A, Tournay AE, Gargus JJ. Genetic inborn error of metabolism provides unique window into molecular mechanisms underlying taurine therapy. Taurine in Health and Disease. 2012:357–369. ISBN: 978-81-7895-520-9. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Novotny EJ, Jr, Fulbright RK, Pearl PL, Gibson KM, Rothman DL. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of neurotransmitters in the human brain. Ann Neurol. 2003;54(Suppl 6):S25–S31. doi: 10.1002/ana.10697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sgaravatti AM, Magnusson AS, Oliveira AS, Mescka F, Zanin F, et al. Effects of 1,4-butanediol administration on oxidative stress in rat brain: Study of the neurotoxicity of γ-hydroxybutyric acid in vivo. J Metabolic Brain Disease. 2009;24:271–282. doi: 10.1007/s11011-009-9136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamakawa Y, Nakazawa T, Ishida A, Saito N, Komatsu M, Matsubara T, Obinata K, Hirose S, Okumura A, Shimizu T. Brain Dev. 2012 Feb;34(2):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2011.05.003. Epub 2011 May 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lapalme-Remis S, Lewis E, Gibson KM, Pearl PL. 99Natural history of SSADH deficiency in adulthood. (Submitted). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ergezinger K, Jeschke R, Frauendienst-Egger G, et al. Monitoring of 4-hydroxybutyric acid levels in body fluids during vigabatrin treatment in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:686–689. doi: 10.1002/ana.10752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]