Abstract

Objective

In the US, young men who have sex with men (YMSM) are disproportionately affected by HIV, with YMSM of color being the most impacted by the epidemic.

Methods

To advance prevention research, we examined race-based differences in gay-related stress in conjunction with the moderating role of mental health on substance use and sexual risk among 206 high-risk YMSM, recruited September 2007–2010.

Results

Negative binomial regressions and three-way interaction graphs indicated that psychological distress and acute gay-related stigma placed all participants at most risk for HIV acquisition. Low psychological distress appeared to “buffer” all YMSM against HIV risk, while the reverse was evidenced for those reporting low gay-related stigma and psychological distress. YMSM of color reported more risk behavior, and less decreases in risk with attenuated psychological distress, compared to white YMSM. We hypothesize these trends to be associated with experiencing multiple stigmatized identities, indicating points of intervention for YMSM of color to achieve positive identity integration. There were sharper increases in HIV risk behavior for white YMSM with increasing gay-related stigma than for YMSM of color, which could be attributed to the latter’s prolonged exposure to discrimination necessitating building coping skills to manage the influx of adversity.

Conclusions

Emphases on: 1) identity-based interventions for YMSM of color; and 2) skills-based interventions for white YMSM should supplement existing successful HIV-risk reduction programs. Lastly, mental health needs to be a target of intervention, as it constitutes a protective factor against HIV risk for all YMSM.

Considerable attention has been given to factors driving infection rates among men who have sex with men (MSM), with significant emphasis on the notion that substance use and condomless sexual behavior function synergistically to exacerbate the burden of HIV incidence and prevalence (Halkitis et al., 2006; Halkitis et al., 2009; Halkitis & Parsons, 2002; Parsons et al., 2013; Stall et al., 2003). As such, substance use is a strong predictor of condomless anal sex (Colfax et al., 2004; Parsons et al., 2013), greater sexual partners, and increased likelihood of HIV seroconversion (Halkitis et al., 2006; Stall et al., 2003; Stall et al., 2001). Further, studies have also sought an explanation for the differential rates of HIV among white MSM and MSM of color. Intriguingly, researcher reports consistently demonstrate lower rates of sexual risk and substance use behavior among MSM of color compared to white MSM, suggesting that behavioral risk factors alone cannot explain the elevated rates of HIV among MSM of color, especially among Black MSM (Bingham et al., 2003; Harawa et al., 2004; Koblin et al., 2006; Millett et al., 2007; Millett et al., 2006). Given the concerning rises in HIV rates among YMSM of color in the U.S., and the high HIV rates maintained among white YMSM (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010, 2012, 2013; Mustanski et al., 2010), it is imperative that we continue to deepen our understanding of HIV risk associations among YMSM of different racial/ethnic groups in order to inform more efficacious, group-specific prevention.

Social factors including stigma and structural barriers in accessing resources and health care have been posited as explanations for discrepancies in HIV rates by race/ethnicity (Donovan, 1997; Heckman et al., 1999; Malebranche et al., 2004; Millett et al., 2006; Peterson et al., 1992), and researchers have called for a shift in prevention by grounding interventions in relevant theories to examine the complexities in which above-individual-level factors contribute to the burden of HIV infection among YMSM of color (Ford et al., 2007; Millett et al., 2012). Below we review literature related to the relationship among perceived sexual minority stigma, mental health, and their association with HIV risk behavior, particularly for YMSM of color.

Emerging literature has explored the relationship between mental health and sexual minority status, and their association with HIV risk behavior (Diaz et al., 2001; Magnus et al., 2010; Hatzenbuehler, 2009, 2010; Stirratt et al., 2008). Minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) has been applied to understand elevated rates of mental health disparities in sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals (Almeida et al., 2009; Hatzenbuehler, 2009, 2010; Hatzenbuehler, 2011). This theory attributes mental health disparities to added stressors (e.g. “hostile and stressful social environment”, Meyer, 2003, p. 674) that come with membership in a stigmatized minority group (e.g., exposure to violence and victimization across one’s lifespan, anticipation and experiences of rejection/discrimination, and internalized homophobia) (Meyer, 2003). Environmental and other external, objective stressors may lead some individuals to expect rejection or internalize social negative attitudes and prejudices (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Meyer, 2003). The anticipation or internalization of stigma can result in escape avoidance, where individuals coping responses could promote risky behaviors, such has sexual risk behavior and substance use (Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2013; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Mustanski et al., 2007; Mustanski et al., 2011).

Further, exposure to gay-related stigma has been associated with poor mental health (Balsam et al., 2011; Diaz et al., 2001), as well as engaging in sexual risk and substance use (Hatzenbuelher et al, 2011), which are especially salient to consider among YMSM of color, who have the complex task of integrating multiple marginalized identities (Balsam et al., 2011; Stirratt et al., 2008). Current research documents that YMSM of color undergo a complex process of coming to terms with their gender, sexual, and ethnic/racial identities, which has been shown to have significant associations with mental health outcomes, such as depression and anxiety (Balsam et al., 2011; Diaz et al., 2001; Meyer & Ouellette, 2009; Stirratt et al., 2008). Social psychology and health research suggest that YMSM of color must manage the multiple burdens of stigma derived from racial/ethnic prejudice, sexual identity-related discrimination, objectification, harassment and ignorance associated with being non-heterosexual and non-white (Battle, 2002; Diaz et al., 2001; Ford et al., 2007; Teunis, 2007; Voisin et al., 2012), which often result in conflict and elevated rates of depression and anxiety.

Moreover, scholars have posited that experiencing gay-related minority stressors has the potential to impact behavior in the form of sexual risk taking due to increased mental health burden resulting from experiences of marginalization and ostracism as sexual minorities (Halkitis, 2010; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2013; Parsons et al., 2013). Poor mental health, including depression and anxiety, has been found to be positively associated with HIV risk behavior (Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2013; Mustanski et al., 2007; Mustanski et al., 2011; Parsons et al., 2013). To date, some studies have found associations between experiences of gay-related stressors, such as internalized homophobia and condomless anal sex among Black MSM (Jeffries IV et al., 2012), and others have found that experienced homophobia increased the likelihood of Latino MSM encountering sexual situations that promote HIV transmission (e.g., having sex while under the influence of substances) (Bruce et al., 2008). As a consequence of these stressors, depression can lead to a lack of adopting and/or maintaining health-promoting behaviors, while anxiety can diminish protection against risk and thus increase odds of contracting HIV (Mustanski et al., 2011).

Given the notable rises in HIV incidence and prevalence rates among YMSM of color in the U.S., as well as the high HIV rates maintained among white YMSM (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010, 2012, 2013; Mustanski et al., 2010), it is imperative that we continue to deepen our understanding of the interactions among gay-related stressors, mental health, and sexual risk behavior for YMSM of different racial backgrounds. To guide the evolution of tailored prevention research, our study aimed to expand on previous findings by hypothesizing that there would be differences in the relationship between stigma, mental health and HIV risk (condomless anal sex and substance use) by race/ethnicity. Specifically, we tested if YMSM of color, compared to white YMSM, would experience higher risk behavior in relation to increased stigma and more acute reports of anxiety and depression due to their exacerbated syndemics in a sample of YMSM of negative or unknown HIV status at risk for HIV acquisition.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

We report on baseline data collected from YMSM recruited in the New York City (NYC) metropolitan area for the Young Men’s Health Project, a study focused on substance use and sexual risk behavior (Golub et al., 2010; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2013; Parsons et al., 2013; Wells et al., 2010). Participants were recruited through a multi-method approach in diverse geographic areas of NYC using techniques previously effective in the recruitment and enrollment of ethnically and racially diverse, substance-using YMSM (Grov et al., 2009; Morgenstern et al., 2009; Parsons et al., 2012). During active recruitment, trained field recruitment staff screened potential participants for eligibility using Palm Pilots in a variety of venues catering to gay, bisexual, and other MSM - including bars, sex venues, streets in predominately gay neighborhoods, and LGBT community events. For passive recruitment, tear-off flyers and project recruitment cards were distributed to potential participants or left on premises of various relevant venues. These cards included a project phone number to be called for eligibility screening. We also used internet-based recruitment (via chat rooms and banner advertisements), friendship referrals, and print advertisement. For the final sample, 71% were enrolled through active field recruitment, 12% through passive recruitment, 9% through internet-based efforts, and 8% through friendship referrals. The 2-hour study visits took place at a research center in NYC, and participants were compensated $40. All participants were English-speaking and assessments were conducted in English. Upon the completion of the baseline assessment, participants were offered the option to enroll in a randomized controlled trial of a behavioral intervention (Parsons et al., 2014). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the investigators’ institution.

Between September 2007- 2010, the study conducted 1,951 eligibility screenings, of which 602 men were preliminarily eligible. Eligible participants were: born and self-identified as male; at least 18 years of age; reported a negative or unknown HIV status; had used drugs – specifically cocaine, methamphetamine, GHB, ecstasy, Ketamine, or poppers – on at least 5 of the past 90 days; and had at least 1 incident of condomless anal sex with a high risk partner (HIV-positive or unknown status main partner or casual partners of any HIV status) in the past 90 days. A total of 351 eligible men presented for a baseline assessment, of which 36 men were dropped from the study for various reasons (e.g., participant-initiated withdrawal, having reported a false HIV negative/unknown status, incarceration, etc), resulting in a total final sample of 315 men. As our interest is to document patterns of HIV risk associations among YMSM, the current analyses drew on a subsample of the Young Men’s Health Project by specifically including only participants between the ages of 18 and 29 (n = 206).

Measures

Demographics

Participants self-reported their age (M = 24.7, SD = 7.1), sexual identity (91% gay), race/ethnicity (66% of color), income (66% earning less than $30,000 annually), education (78% having at least some college education), and relationship status (76% being single) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of sample (N=206).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black | 39 | 19% |

| Latino | 70 | 34% |

| White | 71 | 34% |

| Other/Mixed | 26 | 13% |

| Income | ||

| <30K | 136 | 66% |

| >=30K | 70 | 34% |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 45 | 22% |

| At least some college | 161 | 78% |

| Parental Social Class | ||

| Working Class or Poor | 77 | 37% |

| Middle Class and Above | 129 | 63% |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Gay | 187 | 91% |

| Bisexual | 19 | 9% |

| Relationship status | ||

| In a relationship | 50 | 24% |

| Single | 156 | 76% |

In these analyses, we hypothesized that YMSM of color, compared to white YMSM, would experience higher risk behavior in relation to increased stigma and more acute reports of anxiety and depression due to their exacerbated syndemics. We therefore included measures of sexual and substance use behavior, stigma and mental health.

Outcome variables

The outcomes of interest – high risk sex (or condomless anal sex) with a casual partner (overall and under the influence of drugs/alcohol) and number of days of substance use were collected using a 30-day Timeline Follow Back (TLFB) instrument (Parsons et al., 2013; Sobell & Sobell, 1993). Critical life events e.g., vacations, birthdays, paycheck days, parties) were reviewed retrospectively to prompt recall of daily sex and substance use. The TLFB has previously demonstrated good test-retest reliability, convergent validity, and agreement with collateral reports for drug abuse (Fals-Stewart et al., 2000) and sexual behavior (Carey et al., 2001; Weinhardt et al., 1998), and has been previously utilized with substance-using MSM (Irwin et al., 2006; Morgenstern et al., 2009; Velasquez et al., 2009). Staff received extensive training in the administration of the TLFB, and demonstrated skills (reinforced by ongoing review of audiotapes of the TLFB interviews and supervision) in developing rapport with YMSM participants. Staff were also trained in being non-judgmental and sex-positive in order to facilitate honest self-reports and respect the values and behaviors of all participants. Each day was coded for substance use (alone and with sex), heavy drinking (5 or more drinks that day), sexual partner and type (main/casual), and condom use during anal sex.

Predictor variables

The Gay-Related Stigma Scale (GRS) (Frost et al., 2007) is a modified version of the HIV Stigma Scale (Berger et al., 2001). The GRS is a 10-item scale (α=0.93), with a possible range of scores between 10–50, and assesses perceived stigma from friends and family in relation to disclosing sexual orientation. Participants answered, on a scale from 1–4, with questions such as “I have been hurt by how people reacted to learning that I’m GBT” or “Since realizing that I’m GBT, I feel isolated from the rest of the world”. Mental health was operationalized by using anxiety and depression measures, assessed via the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) Scale (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983), a 12-item scale (α =0.85) with a possible range of scores between 0–48. Participants are asked, on a Likert scale, whether they experienced a variety of symptoms in the previous seven days, such as “nervousness or shakiness inside” or “spells of terror or panic”. Lastly, we used participants’ reported race/ethnicity as a predictor of sexual risk and substance use in the past 30 days. Due to the fact that the sample was not large enough to examine associations by type of race/ethnicity (e.g., Black versus white or Hispanic versus white), we had to dichotomize this variable into YMSM of color versus white YMSM subcategories.

Data Analysis

Prior to conducting regression analyses, differences in scores between YMSM of color and white YMSM’s predictor and outcome variables were examined preliminarily to detect possible distribution differences across these two groups by using t-tests. To prepare for conducting regression analyses, we created a dichotomized race/ethnicity variable (due to the aforementioned small cells for the various racial/ethnic groups), mean-centered stigma and mental health scores, and created interaction terms for stigma, mental health and race/ethnicity. Although anxiety and depression measures could plausibly interact differently with our outcomes, based on the separate models we fit for depression and for anxiety, we obtained the same effects, therefore decided to include the combined anxiety and depression scale in the models presented here. Further, the term “poor mental health” indicates that individuals scored high on both anxiety and depression, and vice versa. Preliminary descriptive analyses indicated that although the continuous predictor variables were normally distributed, the outcomes were skewed. Examination of deviance values for the total number of high sex risk acts, number high risk sex acts under the influence, and number of drugs used suggested that the amount of over-dispersion in outcome variables exceeded the tolerance of the Poisson distribution (Coxe et al., 2009): skewness ≥ 2.46, SE = 0.17; kurtosis ≥ 4.67, SE = 0.34. We therefore tested our hypotheses using generalized linear modeling in SPSS version 20. Generalized linear models allows for the specification of error distributions other than normal distributions (Gardner, Mulvey, & Shaw, 1995). The interpretation of these models is similar to that of the ordinary least squares regression models, although a χ2 test of overall model fit is used rather than an F test. Exponentiated regression coefficients, or risk rate (RRs), are used as a standardized effect size. For all dependent variables, we specified the negative binomial distribution with a log link. Similar to the Poisson distribution, the negative binomial is appropriate for count data (i.e., nonnegative integers) with positive skew. Use of the Poisson distribution, however, additionally assumes that the mean is equal to the variance, whereas the negative binomial distribution allows for overdispersion, which is common in sexual behavior and substance use data (Gardner et al., 1995). Therefore, we used negative binomial regression for the models presented in this paper. All continuous predictor variables were standardized (e.g., mean-centered) to ease interpretation of RRs. None of the demographic variables were associated with our outcomes, therefore it was not necessary to adjust for these in our models. After fitting main effects binomial regression models for each outcome and entering the interaction terms, we plotted the three-way interactions for white YMSM and YMSM of color by using variable means to display graphical representations of our findings.

Results

Bivariate preliminary analyses indicated that YMSM of color reported significantly higher stigma scores and substance use, compared to their white counterparts, with no other group differences noted (Table 2). There were no significant differences in mental health, stigma, sexual risk or substance use between Latino and Black YMSM (data not shown).

Table 2.

Mean comparisons for predictors and outcome variables by race.

| White YMSM (n=71)

|

YMSM of Color (n=135)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | |

| Gay Related Stigma * | 16.4 | 5.7 | 10–32 | 19.3 | 7.2 | 0–40 |

| Mental Health | 9.9 | 7.8 | 0–44 | 11.0 | 9.3 | 0–45 |

| Total Number of High Risk Sex Acts | 4.0 | 6.6 | 0–38 | 6.4 | 13.9 | 0–118 |

| Total Number of High Risk Sex Acts Under the Influence | 3.3 | 6.5 | 0–38 | 5.2 | 13.3 | 0–108 |

| Total Number of Drugs Used per Day* | 8.5 | 8.3 | 0–42 | 12.6 | 12.4 | 0–79 |

p<.01

Table 3 presents the simultaneous binomial regression model testing for the three-way interactions.

Table 3.

Outcomes predicted by gay-related stigma, mental health, and race.

| Predictors | Model 1: High Risk Sex Acts | Model 2: High Risk Sex Acts UI | Model 3: Drug Use | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Exp(B) | 95% CI | B | Exp(B) | 95% CI | B | Exp(B) | 95% CI | |

| Stigma | 0.002 | 1.00 | 0.97–1.04 | −0.008 | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | −0.009 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 |

| Mental Health | 0.018 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 0.015 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.03 |

| Race | −0.468* | 0.63 | 0.42–0.93 | −0.605** | 0.55 | 0.34–0.89 | −0.491*** | 0.61 | 0.47–0.80 |

| Stigma* Mental Health | 0.002 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.002 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 |

| Race* Stigma | 0.013 | 1.01 | 0.95–1.08 | 0.017 | 1.02 | 1.94–1.09 | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 |

| Race* Mental Health | −0.011 | 0.99 | 0.94–1.04 | −0.16 | 0.98 | 0.93–1.04 | 0.005 | 1.00 | 0.97–1.04 |

| Stigma* Mental Health* Race | 0.007* | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.011* | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.005* | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 |

|

| |||||||||

| Log likelihood ratio χ2 (7) = 33.82*** | Log likelihood ratio χ2 (7) = 29.65*** | Log likelihood ratio χ2 (7) = 22.66** | |||||||

| R2deviance =0.005 | R2deviance =0.004 | R2deviance =0.002 | |||||||

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

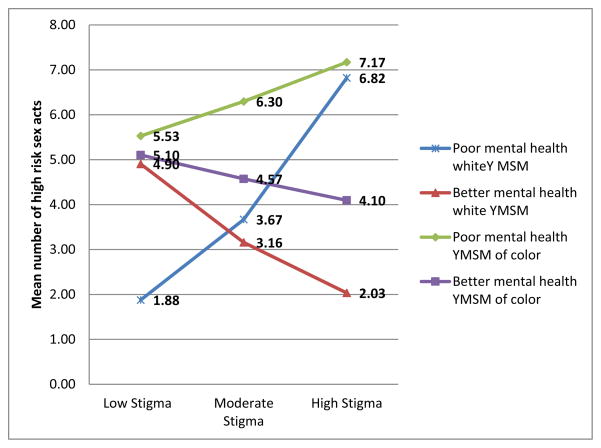

Confirming our hypothesis, race/ethnicity independently predicted the outcome in each model, such that YMSM of color had increased odds of high risk sex (Model 1: B = −0.468, expβ = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.42–0.93, p < .05), high-risk sex under the influence (Model 2: B = −0.605, expβ = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.34–0.89, p < .01), and substance use (Model 3: B = −0.491, expβ = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.47–0.80, p < .001) compared to white YMSM. None of the two-way interaction terms predicted our three outcomes. However, as we hypothesized, the race/ethnicity-stigma-mental health interaction significantly predicted each of our three outcomes: B = 0.007, expβ = 1.01, 95% CI: 1.00 – 1.01, p < .05 for Model 1, high risk sex acts; B = 0.011, expβ: 1.01, 95% CI: 1.0 – 1.2, p < .05 for Model 2, high risk sex acts under the influence; and B = 0.005, expβ = 1.01, 95% CI: 1.00 – 1.02, p < .05 for Model 3, number of drugs used. The interpretation of how the three terms interacted to predict HIV risk differentially for YMSM of color and white YMSM becomes evident by examining their slopes in Figures 1 and 2, described below.

Figure 1.

Mean number of high risk sex acts as a function of mental health and gay-related stigma levels.

Figure 2.

Mean number of drugs used as a function of mental health and gay-related stigma levels.

Figures 1 and 2 display graphical representations of our interaction terms for high risk sex acts and number of drugs used. Results for high risk sex under the influence showed similar trends to those for high risk sex overall, therefore we have omitted a graph for these interactions. The figures elucidate the interaction effects in Table 3, and how these factors interact to create some similar but also notably different trends for white YMSM and YMSM of color. As shown in Figure 1 (high risk sex acts outcome), white YMSM with low gay-related stigma scores and poorer mental health reported fewer high risk sex acts than white YMSM with low gay-related stigma scores and better mental health (M=1.87 vs. M=4.90). As gay-related stigma increases, white YMSM with poorer mental health had greater odds of engaging in high risk sex acts compared to white YMSM with better mental health, for whom a reduction in sexual risk occurred rather than an increase (M=6.82 vs. 2.03). For YMSM of color (Figure 1), those with low gay-related stigma scores, regardless of their mental health status, reported similar numbers of high risk sex acts (M=5.52 and M=5.10). Those with poorer mental health were at higher odds of engaging in high risk sex with increasing stigma, while those with better mental health had less risky sex as stigma increased (M=7.1 vs. M=4.09). Examining these slopes across the racial/ethnic groups, several aspects can be noted. First, all YMSM with poor mental health reported increasing sex risk with increasing stigma, and all YMSM with better mental health reported decreasing sex risk with increasing stigma. Second, YMSM of color reported more sex risk than white YMSM regardless of mental health, and had less of a decrease in high risk sex with improving mental health than their white counterparts. Third, white YMSM with poor mental health evidenced a sharper increase in sex risk with increasing stigma compared to YMSM of color, while white YMSM with better mental health evidenced a sharper decrease in sex risk with increasing stigma compared to YMSM of color. We were unable, however, to test these differences statistically because the groups were underpowered.

Some new patterns were found in the three-way interactions for substance use. Figure 2 illustrates that YMSM of color present notably higher rates of substance use than white YMSM, and those who report poorer mental health maintained a stable rate of substance use with increased stigma (M=14.01). Although we were underpowered to statistically test the differences among the slopes, Figure 2 illustrate that, regardless of race/ethnicity, YMSM who report better mental health are using less drugs as gay-related stigma scores increase (M=12.18 vs. M=9.49). The slopes illustrate visually that reductions in substance use were less drastic for YMSM of color than for white YMSM (M=9.49 vs. M=3.86), which was, again, a difference we were unable to test due to the small cell size within each group. Further, white YMSM who reported poorer mental health showed increases in their substance use as their gay-related stigma scores increased (M=7.10 vs. M=11.36), although it does not reach the same levels as YMSM of color who also reported poorer mental health (M=14.01).

Discussion

Prior studies have shown that gay, bisexual, and other MSM experience high rates of gay-related stigma (Frost et al., 2007) and mental health issues (Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010), and that both of these factors are associated with substance use and sexual risk behavior (Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2013; Parsons et al., 2013). Studies have suggested that YMSM of color report more gay-related stigma, such as negative family reactions to their sexual orientation, compared to white YMSM (Ryan et al., 2009). YMSM of color may also experience increased homophobia from their communities due to less cultural acceptance of sexual diversity (Ford et al., 2007; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2011). They also need to contend with multiple stigmas, which imposed compounded adversity (Voisin et al., 2012). Given the disproportionately growing rates of HIV among YMSM of color, we sought to examine the complexity of race-based differences in the impact of gay-related stigma and mental health on sexual risk behavior and substance use among a community sample of YMSM, postulating that, despite some commonalities, prevention needs and areas of target would vary based on the racial/ethnic group for whom the intervention should be tailored.

We found several similarities between YMSM of color and white YMSM. For all participants, poorer mental health (higher levels of depression/anxiety) and acute experiences of gay-related stigma placed them at most risk for HIV acquisition both in terms of risky sex and substance use. Further, for both white YMSM and YMSM of color, better mental health, even with high levels of gay-related stigma present, appeared to buffer against HIV risk behavior, which was intriguing, although less so for YMSM of color than white YMSM. The reverse was evidenced for those who reported low stigma and better mental health, as they reported increased HIV risk behavior. While these findings seem puzzling, it is possible that YMSM who experience high levels of gay-related stigma (even in the absence of mental health issues) are potentially isolated and disengage from an active social life, which in a gay community often involves substance use and consequently higher rates of condomless sex (Halkitis et al., 2006; Halkitis & Parsons, 2002; Halkitis et al., 2003; Parsons et al., 2006; Parsons et al., 2013); whereas, those not experiencing elevated mental health issues or perceived gay-related stigma may be participating more fully in nightlife and have higher risk exposure. Hatzenbuehler’s “psychological mediation framework” (Hatzenbuehler, 2009) hypothesizes that coping strategies mediate the relationship between gay-related stigma and mental health problems. These pathways include coping/emotional regulation (e.g., strategies used to increase, decrease, or maintain an emotional response), social/interpersonal problems (e.g., isolating oneself from others), and maladaptive cognitive constructs (e.g., negative beliefs about oneself; thoughts of hopelessness). Thus, future research is warranted to examine the ways in which optimal and maladaptive coping strategies may mediate the relationship between gay-related stigma and mental health issues, thereby having the potential to modulate subsequent sexual risk behavior and substance use.

Important differences emerged in this sample, as we originally hypothesized, with YMSM of color reporting overall higher levels of risk behavior, but less decreases in condomless anal sex and substance use with lower reports of mental health issues than evidenced in white YMSM. These trends, evidenced both in the preliminary and final modeling of our current analyses, resonate, as we hypothesized, with the burden associated with carrying multiple identities that are often the target of marginalization by mainstream society, and have been addressed by minority stress theories as explanations for increased risk (Balsam et al., 2011; Meyer, 2003; Stirratt et al., 2008). While we acknowledge that deleterious outcomes for YMSM of color are associated with multiple marginalized identities, these concrete results of stigmatization shed light on points of intervention to shield racial and sexual minorities from socially determined adversity (Hatzenbuehler, 2010) by conveying to them instrumental coping skills.

The ways in which some YMSM are able to cope with stigma become important, especially for intervention purposes. For example, those YMSM of color who are able to achieve a positive integrated identity as a sexual minority person of color report higher self-esteem, greater levels of life satisfaction, and lower levels of mental health issues compared to YMSM who do not achieve an integrated identity (Crawford et al., 2002; Harper et al., 2004; Siegel & Epstein, 1996; Stirratt et al., 2008). Intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991), a strength-based approach, acknowledges that those situated at the intersection of social margins may embrace their difference as a source of strength. In fact, research on identity has shown that people can hold several, even seemingly conflicting identities, while maintaining a coherent unified sense of self (McAdams, 1997; Meyer & Ouellette, 2009; Narváez et al., 2009; Singer, 2004), whose incorporation into prevention research and practice would be beneficial.

The notable high rates of HIV risk behavior among YMSM of color in our sample suggest that additional pathways need to be considered to explain and address these elevated rates of risk behavior. Prevention research needs to incorporate intersections of identity in its components, specifically how YMSM of color cope with gay-related stigma added to feeling stigmatized based on race (Millett et al., 2007; Millett et al., 2012; Millett et al., 2006), and factor in related forms of adversity such as poverty and homelessness. Structural barriers that have been attributed to existing health disparities above and beyond HIV, such as lesser opportunities for education, professional development and suboptimal access to health care and social support resources, need to make their way into the field of prevention in the form of creating more comprehensive interventions. These ought to focus on improving the overall well-being of individuals of color, not on mere reductions of risk acts, and add intervention components that target youth’s educational and vocational development, population-resonant social supports and culturally sensitive health care settings. The racial/ethnic differences we found indicate the need to account for racial/ethnic identity in future research and certainly intervention, above and beyond treating it as a control variable.

Strengths-based prevention is a promising and useful framework to adopt when working with YMSM of color (Lambert et al., 2006; Nicolas et al., 2008), and could also be applied with white YMSM in confronting gay-related stigma. We found sharper increases in HIV risk behavior for white YMSM with increasing gay-related stigma compared to YMSM of color, even with the higher reports of gay-related stigma by YMSM of color in this sample. We interpret these differences as YMSM of color having had prolonged exposure to stigma and discrimination due to their racial/ethnic minority identity, which over time necessitates building coping skills to manage a constant influx of adversity (Nettle & Pleck, 1996). These may protect YMSM of color against sharper increases in risk behavior with increasing gay-related stigma and adverse mental health outcomes, yet do not buffer against existing high levels of risk in our sample. It is also possible that racial/ethnic-based stigma, which we did not measure in this study, supersedes gay-related stigma for YMSM of color, therefore the latter may have had less of an impact on risk behavior in this sample of YMSM of color than it did for white YMSM.

Our findings suggest substantive clinical implications for interventions tailored to different racial/ethnic groups. As such, building white YMSM’s coping skills and mechanisms towards resilience may be key to maintaining low levels of risk and. Conversely, YMSM of color may already have unique coping skills that could be honed to facilitate HIV risk reduction efforts, while supporting their multiple identity integration and self-worth. Thus, emphases on 1) identity-based interventions for YMSM of color and 2) skills-based interventions for white YMSM should be considered to supplement existing successful HIV-risk reduction interventions (Herbst et al., 2007; Herbst et al., 2005; Morgenstern et al., 2009; Morgenstern et al., 2005; Morgenstern et al., 2007; Mustanski et al., 2011; Parsons et al., 2014). Consistent with prior research, our results illustrate that for all YMSM, mental health needs to be a point of intervention in reducing HIV risk regardless of race, as it can act as a protective factor (Safren et al., 2010). As such, behavioral interventions may only be efficacious for those with low levels of anxiety and depression (Safren et al., 2010).

This study is not without limitations. Given that the original scope of the research did not focus on addressing racial/ethnic differences, we did not include a measure of racial/ethnic stigma in our assessments, therefore being unable to account for how much of the risk behavior could be attributed to this aspect. Further, we did not have sufficient power in each group (e.g., YMSM of color vs. white YMSM with low stigma and low mental health issues) to compare differences in risk behavior in the three-way interaction analyses. The same sample size limitation did not allow us to analyze the data based on the range of racial/ethnic groups represented in the study (e.g., Latino, Black/African American, Asian), prompting us to form the non-distinct group of “YMSM of color”, therefore preventing us from observing nuanced differences among racial/ethnic groups of color which other studies have explored. Additionally, the application of our findings to YMSM in general needs caution given that our sample is characterized by quite specific risk profiles, therefore our findings may not be relevant for all YMSM. Lastly, our measures did not include structurally-determined aspects (e.g., poverty, homelessness, survival sex), which are important factors to be included in future research.

Our findings, nevertheless, point to the importance of accounting for individuals’ different sociocultural locations/positions and the valence of their intersectionality to advance HIV preventative efforts in a more meaningful manner that will resonate with their recipients’ identities and overall needs, above and beyond HIV concerns. We also need to think innovatively about the unique prevention needs of YMSM of color. While youth of color may develop coping skills and supportive relationships with others to buffer against adversity (Akers et al., 2010; Arnold & Bailey, 2009), these coping mechanisms do not buffer sufficiently against HIV. For them, HIV transmission has been linked to their social and sexual networks (Fuqua et al., 2012; Millett et al., 2007; Millett et al., 2006; Peterson et al., 2009; Peterson & Jones, 2009; Schneider et al., 2012), which researchers have begun mapping to understand their nature and role as mechanisms for both transmission, but also as potential preventive conduits. Therefore, interventions building on the strengths of YMSM of color’s communities are part of the next generation of prevention approaches.

Acknowledgments

The Young Men’s Health Project was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (R01-DA020366, Jeffrey T. Parsons, Principal Investigator). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors acknowledge the contributions of the Young Men’s Health Project Team—Michael Adams, Aaron Breslow, Christian Grov, Chris Hietikko, Zak Hill-Whilton, Catherine Holder, Anna Johnson, Juline Koken, Mark Pawson, Gregory Payton, Jonathon Rendina, Kevin Robin, Joel Rowe, Tyrel Starks, Anthony Surace, Julia Tomassilli, Andrea Vial, Brooke Wells, and the CHEST recruitment team. We especially appreciate the dedicated commitment of Anthony Bamonte and John Pachankis over the duration of the project, and we gratefully acknowledge Richard Jenkins for his support of the project.

Contributor Information

Corina Lelutiu-Weinberger, Email: clelutiu@hunter.cuny.edu.

Kristi E. Gamarel, Email: kgamarel@hunter.cuny.edu.

Sarit A. Golub, Email: sgolub@hunter.cuny.edu.

Jeffrey T. Parsons, Email: jeffrey.parsons@hunter.cuny.edu.

References

- Akers AY, Youmans S, Lloyd SW, Coker-Appiah DS, Banks B, Blumenthal C, et al. Views of young, rural African Americans of the role of community social institutions’ in HIV prevention. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21:1. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1001–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold EA, Bailey MM. Constructing home and family: How the ballroom community supports African American GLBTQ youth in the face of HIV/AIDS. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services: Issues in Practice, Policy & Research. 2009;21:171–188. doi: 10.1080/10538720902772006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Beadnell B, Simoni J, Walters K. Measuring multiple minority stress: the LGBT people of color microaggressions scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:163–174. doi: 10.1037/a0023244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle J. Say it loud, I’m Black and I’m proud: Black Pride Survey 2000. Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing and Health. 2001;24:518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham TA, Harawa NT, Johnson DF, Secura GM, MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA. The effect of partner characteristics on HIV infection among African American men who have sex with men in the Young Men’s Survey, Los Angeles, 1999–2000. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15:39–52. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.5.39.23613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D, Ramirez-Valles J, Campbell RT. Stigmatization, substance use, and sexual risk behavior among Latino gay and bisexual men and transgender persons. Journal of Drug Issues. 2008;38:235–260. [Google Scholar]

- Carey M, Carey K, Maisto S, Gordon C, Weinhardt L. Assessing sexual risk behaviour with the Timeline Followback (TLFB) approach: Continued development and psychometric evaluation with psychiatric outpatients. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2001;12:365–375. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance in Adolescents and Young Adults. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV Incidence Among Adults and Adolescents in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among African Americans. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, McKirnan D, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, et al. Substance use and sexual risk: A participant-and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159:1002–1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxe S, West SG, Aiken LS. The analysis of count data: A gentle introduction to Poisson regression and its alternatives. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009;91:121–136. doi: 10.1080/00223890802634175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford I, Allison KW, Zamboni BD, Soto T. The influence of dual-identity development on the psychosocial functioning of African-American gay and bisexual men. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39:179–189. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review. 1991;43:1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan P. Confronting a hidden epidemic: The Institute of Medicine’s report on sexually transmitted diseases. Family Planning Perspectives. 1997;29:87–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell T, Freitas T, McFarlin S, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CL, Whetten KD, Hall SA, Kaufman JS, Thrasher AD. Black sexuality, social construction, and research targeting ‘The Down Low’(‘The DL’) Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Parsons JT, Nanin JE. Stigma, concealment and symptoms of depression as explanations for sexually transmitted infections among gay men. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12:636–640. doi: 10.1177/1359105307078170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua V, Chen YH, Packer T, Dowling T, Ick TO, Nguyen B, et al. Using social networks to reach black MSM for HIV testing and linkage to care. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:256–265. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9918-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner W, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:392–404. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub SA, Kowalczyk W, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Parsons JT. Preexposure prophylaxis and predicted condom use among high-risk men who have sex with men. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;54:548–555. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e19a54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Bux D, Jr, Parsons J, Morgenstern J. Recruiting hard-to-reach drug-using men who have sex with men into an intervention study: Lessons learned and implications for applied research. Substance Use and Misuse. 2009;44:1855–1871. doi: 10.3109/10826080802501570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis P, Green K, Carragher D. Methamphetamine use, sexual behavior, and HIV seroconversion. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2006;10:95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis P, Mukherjee P, Palamar J. Longitudinal modeling of methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviors in gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:783–791. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9432-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis P, Parsons J. Recreational drug use and HIV risk sexual behavior among men frequenting urban gay venues. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 2002;14:19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis P, Parsons J, Wilton L. Barebacking among gay and bisexual men in New York City: Explanations for the emergence of intentional unsafe behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32:351–357. doi: 10.1023/a:1024095016181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN. Reframing HIV prevention for gay men in the United States. American Psychologist. 2010;65:752. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.65.8.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harawa NT, Greenland S, Bingham TA, Johnson DF, Cochran SD, Cunningham WE, et al. Associations of race/ethnicity with HIV prevalence and HIV-related behaviors among young men who have sex with men in 7 urban centers in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;35:526–536. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Jernewall N, Zea MC. Giving voice to emerging science and theory for lesbian, gay, and bisexual people of color. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10:187. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. Social factors as determinants of mental health disparities in LGB populations: Implications for public policy. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2010;4:31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127:896–903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Erickson SJ. Minority stress predictors of HIV risk behavior, substance use, and depressive symptoms: Results from a prospective study of bereaved gay men. Health Psychology. 2008;27:455–462. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman TG, Kelly JA, Bogart LM, Kalichman SC, Rompa DJ. HIV risk differences between African-American and white men who have sex with men. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1999;91:92–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Beeker C, Mathew A, McNally T, Passin WF, Kay LS, et al. The effectiveness of individual-, group-, and community-level HIV behavioral risk-reduction interventions for adult men who have sex with men: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:38–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Sherba RT, Crepaz N, DeLuca JB, Zohrabyan L, Stall RD, et al. A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;39:228–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Phillips G, Jones KC, Outlaw AY, Fields SD, Smith JC. Racial and sexual identity-related maltreatment among minority YMSM: Prevalence, perceptions, and the association with emotional distress. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2011;25:S39–S45. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin TW, Morgenstern J, Parsons JT, Wainberg M, Labouvie E. Alcohol and sexual HIV risk behavior among problem drinking men who have sex with men: An event level analysis of timeline followback data. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:299–307. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries WL, IV, Marks G, Lauby J, Murrill CS, Millett GA. Homophobia is associated with sexual behavior that increases risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV infection among black men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;17:1442–1453. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0189-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, Huang Y, Madison M, Mayer K, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20:731–739. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MC, Rowan GT, Longhurst J, Kim S. Strengths as the foundation for intervention with black youth. Reclaiming Children & Youth. 2006;15:147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Pachankis JE, Walker JJ, Bamonte A, Golub SA, Parsons JT. Age cohort differences in the effects of gay-related stigma, anxiety and identification with the gay community on risky sex and substance use. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:340–349. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0070-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus M, Jones K, Phillips G, Binson D, Hightow-Weidman LB, Richards-Clarke C, et al. Characteristics associated with retention among African American and Latino adolescent HIV-positive men: Results from the outreach, care, and prevention to engage HIV-seropositive young MSM of color special project of national significance initiative. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;53:529–536. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b56404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, Peterson JL, Fullilove RE, Stackhouse RW. Race and sexual identity: Perceptions about medical culture and healthcare among Black men who have sex with men. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2004;96:97–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP. The case for unity in the (post) modern self. Self and Identity: Fundamental Issues. 1997;1:46–78. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Ouellette SC. Unity and purpose at the intersections of racial/ethnic and sexual identities. In: Hammack PL, Cohler BJ, editors. The story of sexual identity: Narrative perspectives on the Gay and Lesbian Life Course. New Yor, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2009. pp. 79–106. [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21:2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries WL, Wilson PA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: A meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2012;9839:341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. Journal Information. 2006;96:1007–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Bux D, Jr, Parsons J, Hagman B, Wainberg M, Irwin T. Randomized trial to reduce club drug use and HIV risk behaviors among men who have sex with men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:645–656. doi: 10.1037/a0015588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Irwin T, Parsons JT, Wainberg M, Bux D. Cognitive behavioral risk reduction intervention versus MET for HIV- MSM with alcohol disorders. Paper presented at the Working Group of NIAAA Grantees in the Prevention of HIV/AIDS Meeting; Bethesda, MD. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Irwin T, Wainberg M, Parsons J, Muench F, Bux D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of goal choice interventions for alcohol use disorders among men who have sex with men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:72–84. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, Donenberg G. Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: Preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;34:37–45. doi: 10.1080/08836610701495268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS, Garofalo R, Emerson EM. Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:2426–2432. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS, Newcomb ME, Du Bois SN, Garcia SC, Grov C. HIV in young men who have sex with men: A review of epidemiology, risk and protective factors, and interventions. Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48:218–253. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.558645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narváez RF, Meyer IH, Kertzner RM, Ouellette SC, Gordon AR. A qualitative approach to the intersection of sexual, ethnic, and gender identities. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2009;9:63–86. doi: 10.1080/15283480802579375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nettle SM, Pleck JH. Risk, resilience, and development: The multiple ecologies of black adolescents in the United States. In: Haggerty RJ, Sherrod LR, Garmezy N, Rutter M, editors. Stress, risk, and resilience in children and adolescents: Processes, mechanisms, and interventions. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 147–181. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas G, Helms JE, Jernigan MM, Sass T, Skrzypek A, DeSilva AM. A conceptual framework for understanding the strengths of Black youths. Journal of Black Psychology. 2008;34:261–280. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J, Halkitis P, Bimbi D. Club drug use among young adults frequenting dance clubs and other social venues in New York City. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2006;15:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Botsko M, Golub S. Predictors of day-level sexual risk for young gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:1465–1477. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J, Vial A, Starks T, Golub S. Recruiting drug using men who have sex with men in behavioral intervention trials: A comparison of internet and field-based strategies. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;17:688–699. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0231-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Botsko M, Golub SA. A randomized controlled trial utilizing motivational interviewing to reduce HIV risk and drug use in young gay and bisexual men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;17:2986–2998. doi: 10.1037/a0035311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J, Rothenberg R, Kraft J, Beeker C, Trotter R. Perceived condom norms and HIV risks among social and sexual networks of young African American men who have sex with men. Health Education Research. 2009;24:119–127. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Coates TJ, Catania JA, Middleton L, Hilliard B, Hearst N. High-risk sexual behavior and condom use among gay and bisexual African-American men. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82:1490–1494. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.11.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Jones KT. HIV prevention for Black men who have sex with men in the United States. Journal Information. 2009;99:976–980. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Reisner SL, Herrick A, Mimiaga MJ, Stall RD. Mental health and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;55:S74–S77. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbc939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JA, Walsh T, Cornwell B, Ostrow D, Michaels S, Laumann EO. HIV health center affiliation networks of black men who have sex with men: Disentangling fragmented patterns of HIV prevention service utilization. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2012;39:598–604. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182515cee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Epstein JA. Ethnic-racial differences in psychological stress related to gay lifestyle among HIV-positive men. Psychological Reports. 1996;79:303–312. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1996.79.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JA. Narrative identity and meaning making across the adult lifespan: An introduction. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:437–460. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell M, Sobell L. Problem drinkers: Guided self-change treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:939–942. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, Pollack LM, Bein E, Crosby GM, et al. Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: the Urban Men’s Health Study. Addiction. 2001;96:1589–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirratt MJ, Meyer IH, Ouellette SC, Gara MA. Measuring identity multiplicity and intersectionality: Hierarchical classes analysis (HICLAS) of sexual, racial, and gender identities. Self and Identity. 2008;7:89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Teunis N. Sexual objectification and the construction of whiteness in the gay male community. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2007;9:263–275. doi: 10.1080/13691050601035597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez MM, von Sternberg K, Johnson DH, Green C, Carbonari JP, Parsons JT. Reducing sexual risk behaviors and alcohol use among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:657–667. doi: 10.1037/a0015519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR, Bird JD, Shiu CS, Krieger C. “It’s crazy being a Black, gay youth.” Getting information about HIV prevention: A pilot study. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;36:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt L, Carey M, Maisto S, Carey K, Cohen M, Wickramasinghe S. Reliability of the timeline follow-back sexual behavior interview. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;20:25–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02893805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells BE, Golub SA, Parsons JT. An Integrated Theoretical Approach to Substance Use and Risky Sexual Behavior Among Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;15:509–520. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9767-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]