SUMMARY

Myoendothelial junctions are specialised projections of cell:cell contact through the internal elastic lamina between endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells. These junctions allow for endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells to make direct membrane apposition and are involved in cell:cell communication. In the current study, we evaluated for the presence of myoendothelial junctions in murine corporal tissue and used plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 deficient mice, that lack myoendothelial junctions, to determine if myoendothelial junctions affect erectile function.

Transmission electron microscopy demonstrated the presence of myoendothelial junctions in corporal tissue of wild type mice and confirmed decreased junction numbers in the tissue of PAI-1−/− mice. A potential role for myoendothelial junctions in tumescence was established; in that, PAI-1−/− mice demonstrated a significantly longer time to achieve maximal intracavernous pressure. Treatment of PAI-1−/− mice with recombinant PAI-1 restored the number of myoendothelial junctions in the corporal tissue and also induced a significant decrease in time to maximal corporal pressures. Myoendothelial junctions were similarly identified in human corporal tissue.

These results suggest a critical role for myoendothelial junctions in erectile pathophysiology and therapies aimed at restoring myoendothelial junction numbers in the corporal tissue may provide a novel therapy for erectile dysfunction.

Keywords: Cell communication, endothelial cells, erectile dysfunction, plasminogen activators, vascular smooth muscle

INTRODUCTION

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a major men’s health issue affecting 30 million men in the United States alone and this number is expected to increase two-fold in the next 20 years with the aging population (Haczynski et al., 2006). Normal erectile function requires that a number of different cell types and systems work in concert. This includes neural input from the cavernous nerves and the generation of nitric oxide (NO) by the corporal endothelial cells (ECs) for vascular smooth muscle cell relaxation. This coordinated response leads to vasodilation, expansion of the corpus cavernosum, and the entrapment of blood via compression of the emissary veins (Burnett et al., 1992). Thus, heterocellular signaling or communication between corporal endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscles cells (VSMCs) is essential for a normal erectile response.

Myoendothelial cell junctions (MEJs) are distinct areas in a vessel where cellular extensions pierce through the internal elastic lamina so that the ECs form heterocellular contact with VSMCs (Heberlein et al., 2009). They are unique to the resistance vasculature and are thought to serve as specialised cell-signaling domains, aiding in EC to VSMC communication. Results from several studies suggest that MEJs may play an important role in vasomotor tone and, in certain pathologic conditions where vasoreactivity is altered, changes in the number of MEJs have been noted (Fukao et al., 1997, Makino et al., 2000; Heberlein et al., 2009, 2010).

Formation of MEJs has recently been shown to be associated with the localisation and activity of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) (Heberlein et al., 2010). By inhibiting urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), and thus the plasminogen activator system, PAI-1 aids in maintaining a balance between matrix degradation and cell adhesion. Interestingly, in humans, increased circulating levels of PAI-1 are considered a biomarker for certain vascular disorders. In mice deficient in PAI-1 (PAI-1−/−), significantly fewer MEJs have been noted in several microvascular beds and exposure of PAI-1−/− mice to circulating PAI-1 effectively restored the ability to form MEJs (Heberlein et al., 2010).

Based on the importance of EC – VSMC communication during tumescence and the suggested role of MEJs, we employed wild type (WT), PAI-1−/−, and PAI-1−/− mice treated with recombinant PAI-1 to determine if MEJs have a role in erectile function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

This work was conducted in accordance with the Guiding Principles of the Care and Use of Research Animals promulgated by the University of Virginia. All mice were fed standard chow and maintained on a 12-hour dark-light cycle. All animals used in the studies were eight to ten week-old C57Bl/6 (control wild type; WT; n=7) mice or PAI-1−/− mice (n=7) (Jackson Labs).

Human corporal tissue

Following institutional review board approval, human corporal tissue was obtained from men undergoing penile implant surgery (IRB# 14608). Once retrieved, it was washed in physiologic balanced saline (PBS) and minced into 1 mm pieces. The tissue was subsequently fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde at 4°C and ultrastructural TEM images were obtained as described (Johnstone et al., 2009b).

Electron microscopy on murine corporal tissue

Murine penises were harvested immediately after sacrificing the animals. Corporal tissues, inclusive of the sinusoidal bodies, were carefully dissected and were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde at 4°C and ultrastructural transmission electron microscopic (TEM) images were obtained as described (Johnstone et al., 2009a). Samples were taken from the dorsal aspect of the proximal portion of the penile shaft. The number of MEJs was quantified as previously described (Heberlein et al., 2010).

Intracavernous pressure monitoring

Intracavernous pressures (ICPs) were measured before and during continuous cavernous nerve electrical stimulation (CNES) in murine penises after induction of adequate anesthesia by administering 35-mg/kg sodium pentobarbital intraperitoneally. Baseline ICPs and CNES ICPs were obtained as previously described (Sezen & Burnett, 2000; Boyette et al., 2007). Briefly, the penis was denuded of skin, the scrotum was incised in the midline to offer exposure to the crus of the corpora, and the ischiocavernous muscles were swept off of the tunica albuginea. A heparinised (100 U/ml) 25 gauge needle attached to PE-30 tubing, which was connected to a BD™ pressure transducer (BD™, Franklin Lakes, NJ), was inserted into the cavernous tissue at the crus to monitor ICPs. A low midline abdominal incision was made, the CNs were identified, and CNES was performed with an A-M Systems, Inc.® 2100 isolated pulse generator (A-M Systems, Inc.®, Carlsborg, WA) using 0.2-second pulses of 1.5 mA current at a rate of 20 Hz. Baseline ICPs were obtained and measurements were continued during and after CNES. The ICPs were amplified and recorded using the PolyView 2.1 data acquisition and analysis software system (Grass Technologies, West Warwik, RI).

Systemic administration of recombinant PAI-1 versus saline as controls

Tail vein injections of recombinant PAI-1 (rPAI-1) were performed as previously described (Heberlein et al., 2010). Briefly, fifty microliters of rPAI-1 (1000 ng/μg) or saline was injected into PAI-1−/− mice via the lateral tail vein every 12 hours for five days and the tissue was harvested for TEM.

Statistics

Significance for all experiments was at P<0.05 and determined by one-way ANOVA (Bonferroni post hoc test) or unpaired t-test where noted; error bars are ±SE using Origin Pro 6.0 software.

RESULTS

Characterisation of MEJs in the corpus cavernosum from wild type and PAI-1−/− mice

The presence of MEJs within the corpus cavernosum was established using TEM ultrastructure analysis, performed on sinusoidal bodies from the corporal tissue isolated from WT mice. As evident in Figure 1A, extensions of ECs traversing the internal elastic lamina (IEL) and approaching VSMCs are present in the corporal tissue.

Figure 1. Characterisation and effect of PAI-1 on MEJs in murine corporal tissue.

Ultrastructural TEM images of corpus cavernosum tissue from wild type C57Bl/6 mice (A), PAI-1−/− mice (B), PAI-1−/− mice injected with saline (C), or rPAI-1 injected PAI-1−/− mice (D). The number of MEJs per 10 μm for each experimental paradigm is quantified in (E). In all images, arrows indicate MEJs. Scale bar in is 1 micrometer (μm). In (E), *P<0.05 when compared to wild type. N=7 mice per experimental paradigm, 5 images per mouse.

To determine if the corpus cavernosum from PAI-1−/− mice has reduced MEJs, as has been reported in other vessels from these mice, the corporal tissue inclusive of the sinusoidal bodies were also analysed by TEM. Compared to corporal tissue from WT mice, corporal tissue from PAI-1−/− mice had significantly fewer MEJs (Figures 1B and D).

Treatment with rPAI-1 restores MEJs in the corpus cavernosum of PAI-1 null mice

To determine whether exposure of the PAI-1−/− mice to circulating PAI-1 would restore MEJ formation and numbers, active rPAI-1 or saline control was injected every 12 hours for 5 days via the lateral tail vein (Heberlein et al., 2010). Exposure to circulating rPAI-1 restored MEJ formation to levels observed in WT mice (Figures 1C and D).

PAI-1−/− mice demonstrate an increase in time to achieve maximal ICP

We measured and compared ICPs from WT mice, PAI-1−/− mice and PAI-1−/− mice treated with rPAI-1 to test the functional effects of decreased MEJ formation on erectile function in PAI-1−/− mice. When compared to WT mice, the PAI-1−/− mice displayed a significant increase in the amount of time necessary to achieve tumescence, defined as the time needed to reach maximum ICP after beginning continuous CNES (Figure 2A and B). A representative tracing of an ICP from a WT (blue) and PAI-1−/− (red) mouse is shown in Figure 2A. The change in ICPs during CNES between WT and PAI-1−/− mice was not significantly different, 39±9.3 vs 37±16 mmHg respectively.

Figure 2. Effects of PAI-1 on erectile function.

A representative tracing of ICPs from a wild type mouse (blue) and a PAI-1−/− mouse (red) is displayed. The arrow indicates CNES (A). The time taken to achieve maximum intracavernous pressure (ICP) is quantified from wild type C57Bl/6 mice, PAI-1−/− mice and rPAI-1 injected PAI-1−/− mice (B). N=7 mice per experimental paradigm. *P<0.05.

To test whether the changes in erectile function were associated with changes in MEJ formation, we treated PAI-1−/− mice with rPAI-1 to restore MEJ formation (Figure 1B and C). Following treatment with rPAI-1, we detected no significant difference in the time needed to reach maximum ICP (Figure 2B), suggesting MEJs may play an important role in the transmission of signals necessary to achieve an increase in ICP in a timely manner. While quantification of gap junctions was not performed, our previous research has demonstrated no change in the expression of vascular specific connexins or gap junction function with the addition of rPAI-1 (Heberlein et al., 2010).

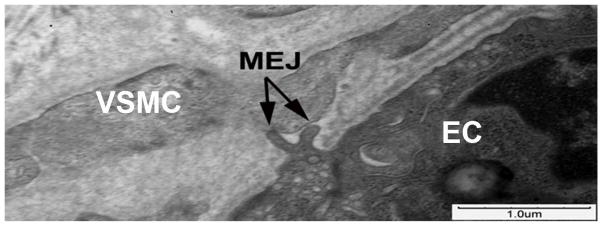

MEJs in the human corpus cavernosum

Based on the above data, that MEJs may have a functional role in tumescence, we sought to determine if they were present in human corporal tissue. TEM of human corporal tissue indeed revealed MEJs with the characteristic EC extension penetrating through the IEL to contact the VSMC (Figure 3).

Figure 3. MEJs in human corporal tissue.

Ultrastructural TEM images of human corporal tissue reveals the presence of an MEJ (arrow) between a corporal EC and VSMC.

DISCUSSION

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is clinically defined as the inability to achieve and maintain an erection, sufficient for satisfactory sexual performance.(NIH, 1992) Importantly, normal erectile function is the result of the coordinated interplay of several physiological systems and the cause of ED can result from a defect in one or multiple components, including normal vascular function (Adams et al., 1997, Albersen et al., 2011). Vasculogenic ED is the result of disruption of vascular mechanisms that promote the ability of VSMCs to relax, a key factor in tumescence (Albersen et al., 2011). As such, we examined a potential role in erectile function for MEJs, a prominent signaling conduit in the resistance vasculature now shown in this study to be present in the corpus cavernosum (Figures 1 and 3) (Heberlein et al., 2009).

While MEJs have been reported in the resistance vasculature, they have not been reported in the corpus cavernosum of either the mouse or human; thus, initial studies were simply to identify if MEJs are present in the corpus cavernosum. The presence of MEJs in both the mouse and human corporal tissue indicates that MEJs are not only in the resistance vasculature but also within the venous lacunae of the corporal bodies and suggests they may be important for efficient communication between corporal EC and VSMCs (Figures 1 and 3).

The development of vasculogenic ED results from the deregulation of normal vascular mechanisms. The MEJ is suggested to be crucial for the coordination of vascular signaling which has been indirectly associated with several vascular disease states (Fukao et al., 1997, Makino et al., 2000; Heberlein et al., 2009; Heberlein et al., 2010). We hypothesised the MEJ may also be crucial for normal erectile function and that loss of MEJ formation in the corpus cavernosum would result in ED. To test this hypothesis, we used a genetic model, PAI-1−/− mice, which were previously characterised as having abrogated MEJ formation and quantified MEJ formation in the corpus cavernosum, as well as measured erectile function (Heberlein et al., 2010). When compared to WT mice, the PAI-1−/− mice had significantly fewer MEJs present in the vasculature of the corpus cavernosum (Figure 1) and took significantly longer to reach maximum ICP (Figure 2). It has been suggested that the inhibition of uPA by PAI-1 decreases extracellular matrix degradation and maintains localised areas of extracellular matrix to aid the extensions of the ECs to penetrate the IEL and form MEJs.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is the major regulator of the fibrinolytic system, mediating the activation of the two plasminogen activators (PAs), effectively controlling the degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components (Lijnen, 2005). Indeed, in pathological conditions where PAI-1 is increased, there is a propensity for fibrotic conditions to occur (Ghosh & Vaughan, 2012). Paradoxically, there are some instances where depletion of PAI-1 has led to fibrotic conditions, likely through a TGF-β mediated mechanism (Ghosh et al., 2010, Ghosh & Vaughan, 2012). The activation of TGF-β is enhanced by various forms of αv integrins that are found at the cell surface and regulated by PAI-1 mediated internalisation (Czekay et al., 2003). When integrins remain at the cell surface, as shown in cells with depleted PAI-1, there is an enhancement of TGF-β activity, which leads to increased collagen deposition and tissue fibrosis (Pedroja et al., 2009; Ghosh & Vaughan, 2012). Importantly TGF-β expression has been correlated with corporal veno-occlusive dysfunction in humans (Nehra et al., 1996).

In the penis, fibrosis is an additional risk factor for the development of vasculogenic ED (Nehra et al., 1996; Gonzalez-Cadavid, 2009). It is possible that the increased matrix production observed in the PAI-1−/− mice may also contribute to ED. Interestingly, it has recently been suggested that ED due to injury of the cavernous nerve, which is common in patients undergoing a radical prostatectomy, may be due to an increase in TGF-β signaling and the progression of penile fibrosis (Moreland et al., 1998; Jin et al., 2010; Cho et al., 2011). While the mechanism for MEJ formation has yet to be further defined, it has been shown using an in vitro model of the MEJ, that MEJs are unable to form through an ECM comprised of collagen (Heberlein et al., 2010). This suggests that an increase in collagen production, as seen in cases of penile fibrosis, may inhibit the formation of MEJs and disrupt the vascular signaling pathways important for the relaxation of VSMC and erectile function.

Conclusions

MEJs exist between ECs and VSMCs in the human and murine corpus cavernosum and are specialised structures for cell-cell signaling pathways that are important to erectile function. In a genetic model of MEJ deficiency (PAI-1−/− mice), a significant increase in the time to reach maximum intracorporal pressure was observed suggesting an important role for MEJs in EC-VSMC communication and normal erectile function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan Redick and Stacey Guillot at the University of Virginia Advanced Microscopy Core for extensive help with electron microscopy. This work was supported by NIH HL088554 (BEI), AHA SDG (BEI), an AHA pre-doctoral fellowship (KRH), and an NRSA post-doctoral fellowship (ACS).

Abbreviations

- CNES

Cavernous nerve electrical stimulation

- EC

Endothelial cells

- ED

Erectile dysfunction

- ICP

Intracavernous pressure

- MEJ

Myoendothelial junctions

- PAI

Plasminogen activator inhibitor

- rPAI-1

Recombinant plasminogen activator inhibitor

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- uPA

Urokinase plasminogen activator

- VSMC

Vascular smooth muscle cells

- WT

Wild type

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ADAMS MA, BANTING JD, MAURICE DH, MORALES A, HEATON JP. Vascular control mechanisms in penile erection: phylogeny and the inevitability of multiple and overlapping systems. Int J Impot Res. 1997;9:85–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALBERSEN M, MWAMUKONDA KB, SHINDEL AW, LUE TF. Evaluation and treatment of erectile dysfunction. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:201–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYETTE LB, REARDON MA, MIRELMAN AJ, KIRKLEY TD, LYSIAK JJ, TUTTLE JB, STEERS WD. Fiberoptic imaging of cavernous nerves in vivo. J Urol. 2007;178:2694–2700. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNETT AL, LOWENSTEIN CJ, BREDT DS, CHANG TS, SNYDER SH. Nitric oxide: a physiologic mediator of penile erection. Science. 1992;257:401–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1378650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHO MC, PARK K, CHAI JS, LEE SH, KIM SW, PAICK JS. Involvement of sphingosine-1-phosphate/RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling pathway in corporal fibrosis following cavernous nerve injury in male rats. J Sex Med. 2011;8:712–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CZEKAY RP, AERTGEERTS K, CURRIDEN SA, LOSKUTOFF DJ. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 detaches cells from extracellular matrices by inactivating integrins. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:781–791. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUKAO M, HATTORI Y, KANNO M, SAKUMA I, KITABATAKE A. Alterations in endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization and relaxation in mesenteric arteries from streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1383–1391. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHOSH AK, BRADHAM WS, GLEAVES LA, DE TAEYE B, MURPHY SB, COVINGTON JW, VAUGHAN DE. Genetic deficiency of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promotes cardiac fibrosis in aged mice: involvement of constitutive transforming growth factor-beta signaling and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Circulation. 2010;122:1200–1209. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.955245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHOSH AK, VAUGHAN DE. PAI-1 in tissue fibrosis. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:493–507. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ-CADAVID NF. Mechanisms of penile fibrosis. J Sex Med. 2009;6 (Suppl 3):353–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HACZYNSKI J, LEW-STAROWICZ Z, DAREWICZ B, KRAJKA K, PIOTROWICZ R, CIESIELSKA B. The prevalence of erectile dysfunction in men visiting outpatient clinics. Int J Impot Res. 2006;18:359–363. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEBERLEIN KR, STRAUB AC, BEST AK, GREYSON MA, LOOFT-WILSON RC, SHARMA PR, MEHER A, LEITINGER N, ISAKSON BE. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 regulates myoendothelial junction formation. Circ Res. 2010;106:1092–102. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.215723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEBERLEIN KR, STRAUB AC, ISAKSON BE. The myoendothelial junction: breaking through the matrix? Microcirculation. 2009;16:307–322. doi: 10.1080/10739680902744404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIN HR, CHUNG YG, KIM WJ, ZHANG LW, PIAO S, TUVSHINTUR B, YIN GN, SHIN SH, TUMURBAATAR M, HAN JY, RYU JK, SUH JK. A mouse model of cavernous nerve injury-induced erectile dysfunction: functional and morphological characterization of the corpus cavernosum. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3351–3364. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSTONE SR, ROSS J, RIZZO MJ, STRAUB AC, LAMPE PD, LEITINGER N, ISAKSON BE. Oxidized phospholipid species promote in vivo differential cx43 phosphorylation and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Pathol. 2009a;175:916–924. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSTONE SR, ROSS J, RIZZO MJ, STRAUB AC, LAMPE PD, LEITINGER N, ISAKSON BE. Oxidized phospholipid species promote in vivo differential cx43 phosphorylation and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Pathol. 2009b;175:916–924. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIJNEN HR. Pleiotropic functions of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:35–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAKINO A, OHUCHI K, KAMATA K. Mechanisms underlying the attenuation of endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in the mesenteric arterial bed of the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:549–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORELAND RB, GUPTA S, GOLDSTEIN I, TRAISH A. Cyclic AMP modulates TGF-beta 1-induced fibrillar collagen synthesis in cultured human corpus cavernosum smooth muscle cells. Int J Impot Res. 1998;10:159–163. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEHRA A, GOLDSTEIN I, PABBY A, NUGENT M, HUANG YH, DE LAS MORENAS A, KRANE RJ, UDELSON D, SAENZ DE TEJADA I, MORELAND RB. Mechanisms of venous leakage: a prospective clinicopathological correlation of corporeal function and structure. J Urol. 1996;156:1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65578-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH. Impotence. NIH Consensus Statement. 1992;10:1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEDROJA BS, KANG LE, IMAS AO, CARMELIET P, BERNSTEIN AM. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 regulates integrin alphavbeta3 expression and autocrine transforming growth factor beta signaling. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20708–20717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEZEN SF, BURNETT AL. Intracavernosal pressure monitoring in mice: responses to electrical stimulation of the cavernous nerve and to intracavernosal drug administration. J Androl. 2000;21:311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]