Abstract

We designed a decision analysis model comparing four treatment strategies for severe sickle cell disease: no intervention, hydroxyurea, chronic transfusion, or stem cell transplant. The treatment strategy associated with the highest average utility (quality of life) was stem cell transplant (0.85). Average utilities for no treatment, chronic transfusion, and hydroxyurea were 0.68, 0.71, and 0.80, respectively. Our model was quite sensitive to quality of life estimates, indicating that a true comparison of hydroxyurea and transplantation cannot occur until investigators directly measure the health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease during hydroxyurea therapy and after stem cell transplant.

Keywords: Sickle cell disease, sickle cell anemia, decision analysis, decision making, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disease in which the substitution of a single amino acid causes the production of the abnormal hemoglobin S. Despite a common genotype, there is a large degree of clinical variability in the pattern and severity of disease manifestations. Patients with a history of sickle cell-related complications, such as recurrent acute chest syndrome and three or more episodes of vaso-occlusive events within 12 months have been classified as having severe disease in previous clinical trials for adult and pediatric patients with SCD [1-3].

To date, three interventional treatments have been separately tested and shown to be effective in decreasing the acute and long-term complications of sickle cell disease: hydroxyurea therapy, chronic transfusions, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [1, 3, 4]. These treatments have different efficacy and toxicity rates, but no randomized studies have been conducted to compare them directly. Because of the variation in risk-benefit profiles for each intervention, there is little consensus among sickle cell clinicians when recommending a therapy.

When definitive answers from randomized clinical trials are not available to answer a clinical question, decision analysis can be used as a tool in medical decision making. In this simulation model-based technique, an investigator combines information from a variety of sources to create a mathematical model representing a clinical decision [5]. First, the investigator structures the clinical problem as a decision tree representing the temporal sequence of possible clinical events. Next, data are collected to estimate the probability of each event, as well as the expected risks, benefits, and sometimes costs of each strategy. The decision tree is then analyzed to identify which strategy has the highest expected value, and is therefore the preferred course of action. The probabilities for an outcome or health state should be estimated from the best available information source, such as a significant clinical trial published in the area.

Decision analysis can also consider the patient's individual preference for a health state (utility). Health state utilities are usually assessed relative to two extremes, referred to as anchor states. Commonly used anchor states are “death,” assigned value of 0, and “live in perfect health”, assigned value of 1. Utility can be estimated or measured. Estimation can be performed in three different ways: arbitrarily assigning values based on an expert's judgment, asking a group of experts to reach a consensus, or searching for relevant published utility values in the literature. Utility can be directly measured in subjects using reliable and valid techniques such as time-trade off, standard gambling, and visual analog scales [6]. Utility can also be measured using preference-based quality of life inventories such as the Health Utility Index or the EuroQol-5D.

Few decision analysis studies have been published in sickle cell disease. Mazumdar et al explored the optimal frequency of transcranial Doppler screening [7]. Nietert et al compared stem cell transplant to periodic blood transfusions in patients with abnormal transcranial Dopplers [8]. Our objective was to develop a preliminary decision analysis model for pediatric patients with severe sickle cell disease due to recurrent vaso-occlusive events to identify key variables of interest to guide future research. The model takes into account current knowledge of treatment risks and benefits for the three available treatments for sickle cell disease (hydroxyurea, chronic transfusions, and stem cell transplantation) as well as estimated patient preferences for health states.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

As reviewed by Burd and Sonnenberg, there are four basic steps to applying decision analysis to a given clinical dilemma [5]. These steps include: 1) identify and define the scope of the problem, 2) structure the problem in the form of a decision tree, 3) collect data to estimate the probability of each event and quantify outcomes, and 4) analyze the decision tree to determine the preferred course of action.

Identify and define the scope of the problem

In decision analysis, it is critical to precisely define both the patient population under study, and the clinical strategies being compared. In our model, the study population was comprised of patients with clinically severe SCD followed over a five-year time period. Although the appropriate definition of severe SCD remains debated within the field, we chose a definition used in previously published multicenter studies of hydroxyurea and stem cell transplant [1-3, 9]. Therefore, severe disease was defined as patients with HbSS or HbSβ°thalassemia and ≥2 acute chest syndrome events in a two-year period, ≥3 pain episodes requiring emergency room visit or hospital admission in a 12-month period, or a combination of any of the two totaling 3 episodes in a 12-month period. The clinical decision in our model involves a choice between 1) no intervention, 2) hydroxyurea (HU), 3) chronic transfusion (CTX), and 4) stem cell transplant (SCT).

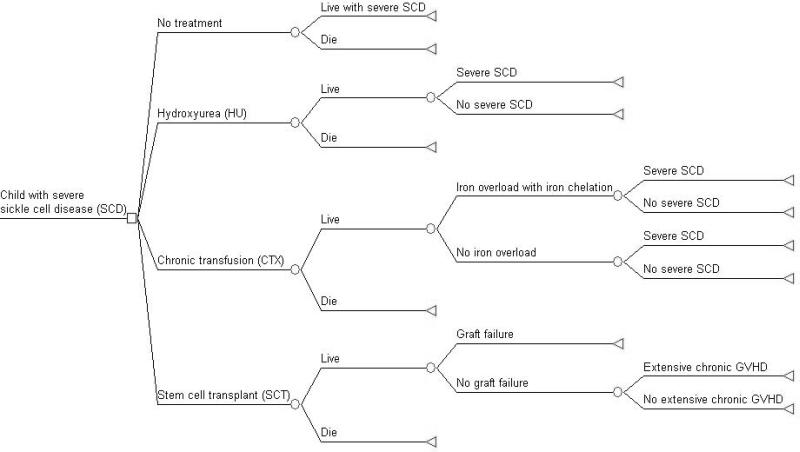

Constructing the decision tree

Once the study population and problem are defined, the problem is structured in the form of a decision tree (Figure 1). The square node represents the decision to choose one of four possible treatment strategies. Once the strategy has been chosen, subsequent events occur by chance, and are called “chance nodes” represented by circles, such as the chance of developing graft versus host disease after a stem cell transplant. At the end of each tree branch is a terminal node (represented by a triangle) which represents the health outcomes associated with the full sequence of events in that pathway. In this model, the health outcome of interested was quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). We constructed and analyzed our model using TreeAge Pro Suite 2008 (TreeAge, Williamstown, MA).

FIGURE ONE.

A schematic representation of the decision analysis model. The square node on the left represents the decision to choose one of four possible treatment strategies. Circular nodes represent chance events, such as the five-year probability of iron overload, graft failure, or death. Triangular nodes at the end of each path in the tree represent the health state utility (quality of life) associated with the full sequence of events in that particular path.

Estimating probabilities and outcome measures

Model estimation involves assigning estimates for clinical probabilities and quality of life measures to each branch of the decision tree. Usually the exact value cannot be estimated with certainty. Therefore, the value that is believed to be the best estimate is used in the base case analysis. We obtained probabilities for most health states from a literature search using PubMed and OVID search engines. The following key words were used: sickle cell disease, hydroxyurea, chronic transfusion, stem cell transplant, mortality, side effects, pediatrics, children, iron overload, GVHD, and graft failure. Five- year probabilities for survival, treatment efficacies, and complications were extracted from published pediatric studies (Table 1). When more than one study was available for a particular clinical probability, the study with the largest sample size was used for the base case estimate. Utilities for various health states were estimated by a physician with experience in treating patients with sickle cell disease (JSH), based on values used in a published decision analysis comparing stem cell transplant to chronic transfusion in SCD patients with abnormal transcranial Dopplers [8]. Our utility estimates for SCD (0.7 for untreated severe SCD) were also comparable to those reported for more common chronic conditions in the Health and Activity Limitation Index (HALex), such as diabetes (mean HALex=0.62) and congenital heart disease (mean HALex=0.68) [10]. As death from iron overload due to heart dysfunction from myocardium iron accumulation is extremely low in SCD, particularly in our brief five-year time period, mortality attributed to blood transfusions was estimated based on mortality rates from transfusion-associated lung injury [11, 12]. No deaths attributed to hydroxyurea therapy have been found in the literature in the pediatric population, and an adult study of long-term use of hydroxyurea did not find hydroxyurea toxicity as the cause of death in a cohort of 152 treated adults [13, 14].

TABLE 1. Estimates for Clinical Probabilities and Quality of Life Measures.

For clinical probabilities, base case estimates were extracted from published pediatric studies with the largest sample size. The range of estimates was based on all identified studies in the pediatric literature, or from adult literature if pediatric-specific data were not available. For utility estimates, the range is the base case estimate ± 0.2.

| Base case estimate | Range | References or sources | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLINICAL PARAMETERS | |||

| Probability of severe SCD | |||

| Hydroxyurea (HU) | 27% | 20-45% | [2, 18-22] |

| Chronic transfusion (CTX) | 15% | 6-15% | [4, 23, 24] |

| Probability of mortality | |||

| No treatment | 3% | 1-40% | [25, 26] |

| Hydroxyurea | 0% | 0-10% | [14, 27] |

| Chronic transfusion | 1.1% | 1-50% | [11] |

| Stem Cell Transplant (SCT) | 6% | 1-10% | [3, 28-30] |

| Probability of iron overload with CTX | 95% | 0-100% | [31, 32] |

| Probability of graft failure with SCT | 10% | 10-18% | [3, 28-30] |

| Probability of chronic GVHD with SCT | 3.8% | 7.7-22% | [3, 28-30] |

| QUALITY OF LIFE MEASURES (UTILITIES) | |||

| Alive, no treatment, severe disease | 0.7 | 0.5-0.9 | [8, 10] |

| Alive, on HU, severe disease | 0.65 | 0.45-0.85 | [8, 10] |

| Alive, on HU, no severe disease | 0.85 | 0.65-1 | [8, 10] |

| Alive, on CTX, severe disease, iron overload | 0.55 | 0.35-0.75 | [8, 10] |

| Alive, on CTX, no severe disease, iron overload | 0.75 | 0.55-0.95 | [8, 10] |

| Alive, on CTX, severe disease, no iron overload | 0.60 | 0.40-0.80 | [8, 10] |

| Alive, on CTX, no severe disease, no iron overload | 0.80 | 0.60-1 | [8, 10] |

| Alive, SCT, graft failure | 0.55 | 0.35-0.75 | [8, 10] |

| Alive, SCT, no graft failure, chronic GVHD | 0.65 | 0.45-0.85 | [8, 10] |

| Alive, SCT, no graft failure, no chronic GVHD | 0.95 | 0.75-1 | [8, 10] |

| Death | 0 | --- | [8, 10] |

Choosing the preferred course of action (model analysis)

Decision trees are analyzed from right to left using a process called rolling back. In this model, each chance node was assigned a value equal to the sum of the utility for each branch weighted by their respective probabilities. The strategy associated with the highest utility was defined as the preferred course of action.

Sensitivity analysis is an important tool for handling the uncertainty inherent in any decision analysis model and evaluates the effect of alternative assumptions on the final result. If changing a variable over a reasonable range of values changes the preferred strategy, the model is considered sensitive to that variable. We performed one-way sensitivity analysis, in which each model input is varied one at a time, for all probabilities and utilities in the model (Table 1). All probabilities from published pediatric studies, or in a few cases adult studies, were used as plausible ranges in sensitivity analysis for clinical probabilities. Finally, we performed an additional sensitivity analysis in which we varied probabilities widely to identify any threshold values at which the preferred strategy changed. Due to the uncertainty in utility estimates, each estimate was widely ranged between +0.2 and −0.2 the baseline utility.

RESULTS

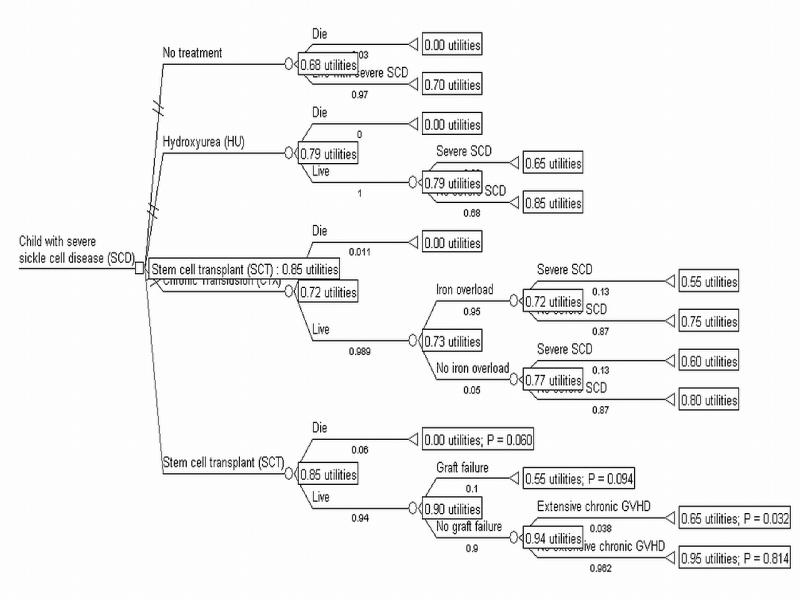

Analysis, or rolling back, or our decision tree revealed that the treatment strategy associated with the highest average utility (quality of life) over a five-year period was stem cell transplant (0.85) (Figure 2). Average utilities for no treatment, chronic transfusion, and hydroxyurea were 0.68, 0.71, and 0.80 respectively. (To put these numbers into perspective, recall that utilities range from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health).)

FIGURE TWO.

The decision analysis model after rollback analysis. The stem cell transplant strategy has the highest quality of life, which an average utility of 0.85. Numbers under each branch of the tree represent the probability estimate used in the base case analysis. For example, the mortality of stem cell transplant was estimated to be 6%.

One-way sensitivity analysis of clinical parameters over plausible ranges based on variation seen in the published literature revealed that stem cell transplant was the preferred strategy in the large majority of scenarios. One exception was that if the estimated utility of a patient status-post SCT was <0.89, then HU would be preferred over SCT (Table 2). When varying probability estimates over ranges beyond our original sensitivity analysis, we identified additional scenarios in which hydroxyurea would be preferred over stem cell transplant; for example, if the mortality of SCT is >11%, or the probability of graft failure is >23%.

TABLE 2. Threshold Values Identified in Sensitivity Analysis.

We performed one-way sensitivity analysis, in which the value of each clinical probability and quality of life estimate was varied one at a time over a wide range of values. In the majority of cases, estimates had to be varied outside of the plausible range for an intervention other than stem cell transplant to be the preferred strategy.

| Plausible range based on published literature | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| CLINICAL PARAMETERS | ||

| Probability of severe SCD | ||

| Hydroxyurea (HU) | 20-45% | If probability of severe disease <1%, HU preferred over SCT If probability of severe disease >60%, CTX preferred over HU |

| Chronic transfusion (CTX) | 6-15% | If probability of severe disease >43%, no treatment preferred |

| Probability of mortality | ||

| Hydroxyurea | 0-10% | SCT always preferred |

| Chronic transfusion | 1-50% | SCT always preferred |

| Stem Cell Transplant (SCT) | 1-10% | If SCT mortality ≥11%, HU becomes preferred strategy |

| Probability of iron overload with CTX | 0-100% | SCT always preferred |

| Probability of graft failure with SCT | 10-18% | If probability of graft failure ≥23%, HU becomes preferred strategy |

| Probability of chronic GVHD with SCT | 7.7-14% | If probability of GVHD ≥23%, HU becomes preferred strategy |

| QUALITY OF LIFE MEASURES (UTILITIES) | ||

| Alive, on HU, severe disease | 0.45-0.85 | If utility >0.843, HU becomes preferred strategy |

| Alive, on HU, no severe disease | 0.65-1 | If utility >0.914, HU becomes preferred strategy |

| Alive, on CTX, severe disease, iron overload | 0.35-0.75 | SCT always preferred |

| Alive, on CTX, no severe disease, iron overload | 0.55-0.95 | SCT always preferred |

| Alive, on CTX, severe disease, no iron overload | 0.40-0.80 | SCT always preferred |

| Alive, on CTX, no severe disease, no iron overload | 0.60-1 | SCT always preferred |

| Alive, SCT, graft failure | 0.35-0.75 | If utility is <0.04, SCT no longer preferred |

| Alive, SCT, no graft failure, chronic GVHD | 0.45-0.85 | SCT always preferred |

| Alive, SCT, no graft failure, no chronic GVHD | 0.75-1 | If utility is <0.89, HU becomes preferred strategy |

We found that our model was more sensitive to variation in quality of life measurements than the probability of clinical complications. When varying utility estimates, we found that our model was quite sensitive to the quality of life experienced by children on hydroxyurea therapy (both those who continue to have severe disease and those who respond well to HU) and the quality of life experienced by children who undergo SCT not complicated by graft failure or chronic GVHD.

DISCUSSION

This appears to be the first time decision analysis has been used to compare treatment strategies in children with clinically severe SCD. We found that stem cell transplant was associated with the highest average quality of life, followed by hydroxyurea and chronic transfusions. Unfortunately, all of the data available regarding SCD and stem cell transplant are based on SCT performed using HLA-matched sibling donors, and <10% of patients with SCD have a matched sibling. Even in patients with matched siblings, however, recommending stem cell transplant over hydroxyurea remains a difficult decision for clinicians as transplant is associated with its own morbidity and low, but not negligible, mortality. The results of our model demonstrate that quality of life is also an important factor to consider in this decision.

Our decision analysis model has several limitations that should be noted. First, our model of SCD only follows patients for five years, and is simplistic given the heterogeneity and complexity of this patient population. Even the definition of “severe sickle cell disease” remains a hotly debated point within the field. Our definition was based on definitions used in the clinical trials we extracted data from. However, this definition does not include patients with stroke or those with repetitive pain episodes which are managed at home but have substantial negative impacts on quality of life. The probability of adherence to therapy and the effects of poor adherence on health outcomes were also not considered. We view this model as a “place to start” in the consideration of the impact of clinical probabilities and quality of life in therapeutic decision making for patients with severe SCD. As more data accumulates on the use of hydroxyurea and stem cell transplant in sickle cell disease, and in particular data on the long term outcome of these patients, we hope that future models will able to handle additional complexity and a longer time frame. As there are few published pediatrics studies, our clinical probability estimates were dependant on small cohorts with limited follow-up periods. Larger studies with much longer longitudinal follow up would allow for more accurate mortality rates. For example, we found that if the mortality of stem cell transplant is ≥11%, then transplant is no longer the preferred strategy, a number that is not much higher than published estimates.

Due to the absence of direct reports of quality of life from patients with SCD, the most important limitation of our study is that health state utilities were estimated by a physician, with input from a previously published decision analysis and the Health and Activity Limitation Index. However, this previously published model comparing stem cell transplant to chronic transfusion in SCD patients with abnormal transcranial Doppler was similarly limited [8]. Ideally, utilities should be measured directly from patients experiencing the health state in question, which can be done in several different ways. An investigator can measure utilities directly by performing a choice-based valuation technique such as the standard gamble or time trade-off [15]. However, these are time consuming and complex tasks. They are particularly challenging in pediatric research because they require a lengthy attention span and a minimum sixth-grade reading level [16].

The sensitivity of our model to utility estimates, however, demonstrates the necessity of eliciting quality of life data from children with SCD who undergo stem cell transplant or hydroxyurea therapy. An alternative, and more feasible, method of directly measuring utilities would be to use a pre-scored multiattribute health status classification system, such as the Health Utilities Index or the EuroQol-5D [6]. Formulas have been developed to calculate utilities using patient responses to these generic quality-of-life instruments, which are easier and faster to administer and require less advanced reading levels. Panepinto et al recently showed the feasibility of directly measuring utilities by demonstrating that the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory generic core scales (PedsQL) is a feasible, reliable, and valid tool to measure health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease, and that the parent proxy-report differentiates well between children with mild and severe disease [17].

In summary, we performed an initial decision analysis model to identify variables of interest when comparing four clinical strategies for severe sickle cell disease - no treatment, hydroxyurea therapy, chronic transfusions, and stem cell transplantation. Our model reveals that a true comparison of hydroxyurea and stem cell transplant, the two most attractive strategies, cannot occur until investigators directly measure the health-related quality of life in sickle cell patients after stem cell transplant and during hydroxyurea therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1317–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferster A, Tahriri P, Vermylen C, et al. Five years of experience with hydroxyurea in children and young adults with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2001;97:3628–32. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walters MC, Storb R, Patience M, et al. Impact of bone marrow transplantation for symptomatic sickle cell disease: an interim report. Multicenter investigation of bone marrow transplantation for sickle cell disease. Blood. 2000;95:1918–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller ST, Wright E, Abboud M, et al. Impact of chronic transfusion on incidence of pain and acute chest syndrome during the Stroke Prevention Trial (STOP) in sickle-cell anemia. J Pediatr. 2001;139:785–9. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.119593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burd RS, Sonnenberg FA. Decision analysis: a basic overview for the pediatric surgeon. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2002;11:46–54. doi: 10.1053/spsu.2002.29370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O'Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 3rd edition. Oxford Unversity Press; Oxford [England]; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazumdar M, Heeney MM, Sox CM, et al. Preventing stroke among children with sickle cell anemia: an analysis of strategies that involve transcranial Doppler testing and chronic transfusion. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1107–16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nietert PJ, Abboud MR, Silverstein MD, et al. Bone marrow transplantation versus periodic prophylactic blood transfusion in sickle cell patients at high risk of ischemic stroke: a decision analysis. Blood. 2000;95:3057–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott JP, Hillery CA, Brown ER, et al. Hydroxyurea therapy in children severely affected with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 1996;128:820–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold MR, Franks P, McCoy KI, et al. Toward consistency in cost-utility analyses: using national measures to create condition-specific values. Med Care. 1998;36:778–92. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199806000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zambon M, Vincent JL. Mortality rates for patients with acute lung injury/ARDS have decreased over time. Chest. 2008;133:1120–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood JC, Tyszka JM, Carson S, et al. Myocardial iron loading in transfusion-dependent thalassemia and sickle cell disease. Blood. 2004;103:1934–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brawley OW, Cornelius LJ, Edwards LR, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement: hydroxyurea treatment for sickle cell disease. Annals of internal medicine. 2008;148:932–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-12-200806170-00220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinberg MH, Barton F, Castro O, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on mortality and morbidity in adult sickle cell anemia: risks and benefits up to 9 years of treatment. JAMA. 2003;289:1645–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Brien SH. Decision analysis in pediatric hematology. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2008;55:287–304, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griebsch I, Coast J, Brown J. Quality-adjusted life-years lack quality in pediatric care: a critical review of published cost-utility studies in child health. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e600–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panepinto JA, Pajewski NM, Foerster LM, et al. The performance of the PedsQL generic core scales in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:666–73. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31817e4a44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferster A, Vermylen C, Cornu G, et al. Hydroxyurea for treatment of severe sickle cell anemia: a pediatric clinical trial. Blood. 1996;88:1960–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hankins JS, Ware RE, Rogers ZR, et al. Long-term hydroxyurea therapy for infants with sickle cell anemia: the HUSOFT extension study. Blood. 2005;106:2269–75. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jayabose S, Tugal O, Sandoval C, et al. Clinical and hematologic effects of hydroxyurea in children with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr. 1996;129:559–65. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koren A, Segal-Kupershmit D, Zalman L, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea in sickle cell anemia: a clinical trial in children and teenagers with severe sickle cell anemia and sickle cell beta-thalassemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;16:221–32. doi: 10.1080/088800199277272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers ZR. Hydroxyurea therapy for diverse pediatric populations with sickle cell disease. Semin Hematol. 1997;34:42–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hankins J, Jeng M, Harris S, et al. Chronic transfusion therapy for children with sickle cell disease and recurrent acute chest syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:158–61. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000157789.73706.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Styles LA, Vichinsky E. Effects of a long-term transfusion regimen on sickle cell-related illnesses. J Pediatr. 1994;125:909–11. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leikin SL, Gallagher D, Kinney TR, et al. Mortality in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatrics. 1989;84:500–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad R, Hasan S, Castro O, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with sickle cell disease and frequent vaso-occlusive crises. Am J Med Sci. 2003;325:107–9. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200303000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakanay SM, Dainer E, Clair B, et al. Mortality in sickle cell patients on hydroxyurea therapy. Blood. 2005;105:545–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernaudin F, Souillet G, Vannier JP, et al. Report of the French experience concerning 26 children transplanted for severe sickle cell disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19(Suppl. 2):112–115. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vermylen C, Cornu G, Ferster A, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for sickle cell anaemia: the first 50 patients transplanted in Belgium. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:1–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panepinto JA, Walters MC, Carreras J, et al. Matched-related donor transplantation for sickle cell disease: report from the Center for International Blood and Transplant Research. British journal of haematology. 2007;137:479–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harmatz P, Butensky E, Quirolo K, et al. Severity of iron overload in patients with sickle cell disease receiving chronic red blood cell transfusion therapy. Blood. 2000;96:76–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karam LB, Disco D, Jackson SM, et al. Liver biopsy results in patients with sickle cell disease on chronic transfusions: poor correlation with ferritin levels. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2008;50:62–5. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]