Abstract

Community groups and local air pollution control agencies have identified the San Bernardino Railyard (SBR) as a significant public health and environmental justice issue. In response, the authors conducted a comprehensive study with community members living in close proximity to the rail yard. The purpose of this article is to share the community's perceptions about the rail yard and ideas on sustainable change. A qualitative study using key informant interviews and focus group discussions was conducted and resulted in four emerging themes. Themes emerged as follows: “health as an unattainable value,” “air quality challenges,” “rail yard pros and cons,” and “violence and unemployment ripple effect.” Community participants expressed concern for poor air quality, but other challenges took priority. The authors' findings suggest that future mitigation work to reduce air pollution exposure should not only focus on reducing risk from air pollution but address significant cooccurring community challenges. A “Health in All Policies” approach is warranted in addressing impacted communities in close proximity to the goods movement industry.

Introduction

The transportation of goods can both promote and adversely impact health. Goods movement activities can promote health, for example, by enabling access to employment and better services. Transportation of goods, however, can also degrade quality of life and be health damaging because of various environmental and societal impacts such as air pollution, climate change, injuries, noise, landscape disruption, loss of sense of community, stress, and anxiety (Mindell, Watkins, & Cohen, 2011). Environmental health scientists are beginning to elucidate the linkages between the air pollution from international trade and goods movement and health (Hricko, 2006, 2008).

Mounting research indicates that persons living near transportation hubs and corridors are exposed to higher levels of airborne pollutants, including diesel exhaust and other emissions. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) has determined that diesel exhaust is “likely to be carcinogenic to humans by inhalation (National Environmental Justice Advisory Committee, 2009).” Health impacts from the air pollution associated with goods movement include respiratory illnesses, increased premature death, risk of heart disease, cancer risk, adverse birth outcomes, effects on the immune system, multiple respiratory effects, and neurotoxicity (Attfield et al., 2012; Brauer et al., 2007; California Air Resources Board [CARB], 2005; Chen, Schreier, Strunk, & Brauer, 2008; Edwards, Walters, & Griffiths, 1994; Hoffmann et al., 2009; Jerrett et al., 2005; Mack, 2004; Salam, Islam, & Gilliland, 2008; Silverman et al., 2012). Furthermore, the strengths of associations described for traffic-related exposures are directly related to the proximity to major roadways (Margolis et al., 2009; Newcomb & Li, 2008). Children are especially vulnerable and those living near freeways have shown to have substantial deficits in lung function and development as well as asthma exacerbations (Gauderman et al., 2007; Gruzieva et al., 2013; Perez et al., 2009; Schultz et al., 2012; Spira-Cohen, Chen, Kendall, Lall, & Thurston, 2011); others have linked traffic exposure to increased risk of low birth weight and premature birth (Brauer et al., 2008).

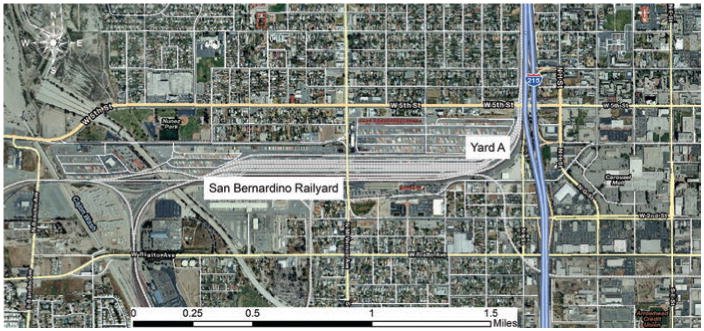

Growing emissions from trucks and trains in regions that contain major segments of the goods movement network can add to existing air quality problems and impact specific local communities. In the city of San Bernardino, California, one such community is located in close proximity to a major freight rail yard. We identified this as the San Bernardino Railyard (SBR). The SBR is one of the busiest facilities of its kind in California and a major inland hub for goods shipped from the ports of Los Angeles (Figure 1). The city of San Bernardino and the railroads have been interlinked throughout the nearly 200-year history of the city, with railroad operations changing to predominately freight-based operations since the 1990s. With operations running 24/7, the SBR is a crucial hub for freight and shipping for the entire U.S. Given the nature and intensity of the work performed at the SBR, it is not unrealistic to think air pollution levels in the immediately surrounding areas would be higher relative to other locations within the city. The potential health impacts could also be significant since the facility is in close proximity to residential neighborhoods and other sensitive receptors such as daycare facilities and an elementary school located within 500 yards of the rail yard.

Figure 1. Aerial Map of the San Bernardino Railyard and Surrounding Community.

Based on the risk assessments conducted by the California Air Resources Board (CARB), the SBR facility ranks among the top five most polluting rail yards in California and first in terms of community health risk due to the large population living in the immediate vicinity (CARB, 2008). Table 1 summarizes the key sociodemographic indicators of the community members residing within one half-mile of the surrounding rail yard, obtained through Census 2010 data and modeled with GIS software. The population immediately around the SBR is defined primarily by young (including a large proportion of children), low income, and largely Latino members. Available health outcomes data suggest tremendous health disparities between the region's African-Americans and Latinos and the Caucasian population. While the overall county's poverty rate is 15.8%, the rate for Latinos stands at 34.9%, which far exceeds the overall poverty rate for the state (14.2%), the nation (12.4%), and even California's Latino poverty rate of 28% (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Further limiting available support for community members was the 2012 bankruptcy of the city of San Bernardino, which made this one of the area's poorest municipalities, with a disproportionate number of neighborhoods facing a host of economic, educational, health, and environmental challenges.

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Community Residing Within One-Half Mile Surrounding the San Bernardino Railyard.

| Sociodemographic Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Total population | 7,172 |

| Households | 1,895 |

| % African-Americans | 9.0 |

| % Hispanics | 82.3 |

| % Children <5 years of age | 11.7 |

| % Children 5–17 years of age | 27.5 |

| Median age (yrs.) | 25.2 |

| Average household size (persons) | 3.9 |

| Median household income | $28,214 |

Fueled by the CARB report on the potential health effects for residents, some community members voiced an urgent call to action to the city's mayor, politicians, and local researchers to address these environmental justice issues. In response, researchers, in collaboration with residents and a local community-based organization, formed the Environmental Railyard Research Impacting Community Health (ENRRICH) Project. Using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) agenda, ENRRICH aimed to explore the health risks of residents living in close proximity to the rail yard and to support the development of a community response plan. While the overall study goals involve quantitative community and child assessments, the initial research phase used qualitative methods to better understand the context of risk experienced by the residents. As a CBPR study, ENRRICH emphasizes the significant role of community input, ownership, and concerted actions in risk reduction to produce appropriate, innovative, and practical solutions that are cost-effective and sustainable (Israel, Eng, Schulz, Parker, & Satcher, 2005). We therefore conducted a qualitative study to gain community member's perspectives about life near the rail yard.

Methods

We conducted this qualitative inquiry using inductive grounded theory (GT) methods that included participant and site observations that were carefully documented. A GT approach was selected because this method gives participants a “voice,” allowing them to share their reality and in fact creating a “theory of their lives,” grounded in their self-described reality. Rather than following up on our own “expert” thoughts, this approach best enabled discovery of the participants' main concerns and how they try to solve the challenges, without any prior preconceived hypothesis influencing the results. Founded on GT methods, we collected resident feedback about their perceptions on life near the rail yard through the conduct of semistructured key informant interviews (N = 12) that were coded and themed. The results were then used to design the validation focus groups (N = 5 with 8–13 participants each). The focus groups were conducted by trained bilingual facilitators and lasted 60–90 minutes. Participants were selected using theoretical sampling to assure triangulation to present a broad variety of perspectives (politicians, community organizers, business owners, and community members representing the local community makeup and in ethnicity breakdowns). More specifically we asked residents about their lives, exploring their perceived quality of life and health challenges, including their perceptions of the potential effects of air pollution on themselves and their children, and their thoughts on the nearby rail yard. Four of the focus groups (two in Spanish with monolingual Latino residents, one each in English with Latino and African-American residents) were conducted at a community center near the SBR, while one (conducted in English) was convened at a nearby homeless shelter. Each participant signed informed consent forms that were approved by the Loma Linda University's institutional review board. All interviews and focus groups were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Once transcribed, the text was coded for emergent codes and a final codebook was developed. Transcripts were read and coded independently by several research assistants, using the coding in conjunction with a constant comparison method; emergent themes were then determined.

Results

A total of 65 adults participated in the key informant interviews and focus groups. Participants included male and female community members ranging in age from 18 to 60+. Four major themes emerged and are described below: 1) violence and unemployment ripple effect, 2) air quality challenges, 3) rail yard pros and cons, and 4) health as an unattainable value. Further analysis of themes led to the integration of all four into one core concept: Experiences of the rail yard community: Life is hard. Table 2 includes a sample of quotes from the community members surrounding each of the identified themes.

Table 2. Community Participant Responses on the Thematic Topics Regarding Life Near A Major Rail Yard.

| Violence and Employment Challenges |

|---|

| Community violence and unemployment rates affected residents' feelings about their exposure to polluted air, ranking it lower than other, more immediate priorities related to day-to-day survival. |

|

1) “Oh. There's a little bit of everything…. People trying to rob you…. You just can find yourself in the wrong place, who knows…you might came up on a nice pair of shoes and this dude comes along with a gun and they will be his.” —Male 2) “…. There's more to worry about than the actual air.”—Hispanic Male 3) “We were at the park…next thing you know, my girls are seeing a stabbing and they, they don't need to see that….”—Female 4) “….Trust me, I want good health, I want good air, I want the city to be awesome by the time my great-grandkids live here, you know what I mean? But by the same token, I think other things need to be fixed beside that.”—Male 5) “…If you're in San Bernardino and you're in the slum ain't nothing gonna change.”—Male |

| Participants reported feeling powerless to reduce the level of violence in their area, and high levels of concern for their children's safety. |

|

6) “I'm worried about the safety of my children…you can't just have them outside….”—Female 7) “I think for the youths, they don't have nothing to do…there's a lot of youngsters from all different areas that hang out right there…these kids need something to do with their lives.”—Female |

| Empty lots with overgrown weeds and businesses that have relocated out of the city: these are some of the factors negatively impacting the health and vitality of their community. |

|

8) “…There is just too many abandoned buildings…”—Female 9) “I've seen this community go from a family neighborhood to run-down or abandoned houses, empty lots, and growing weeds.”—Male 10) “Most of the businesses are leaving San Bernardino for other cities in the area. We used to have a mall down the street; it's all gone now.”—Male |

| Community members said they would like to move out of the area, but couldn't afford to. |

|

11) “I do not like this place, but we chose it because it was the place we could afford. I have lived here for seven years and the city is cheap; we are here because we don't have more resources to be in another area.”—Caucasian Female 12) “Unfortunately this is one of the most economical places to live, but the consequences for living here is too great, not for what you pay financially, but that your health is seriously affected.”—Hispanic Female |

|

|

| Air Quality Challenges |

|

|

| Participants pointed out that children are most vulnerable and voiced a growing concern that poor air quality may be affecting their children's health. |

|

13) “I have a nephew and he has allergies awfully bad and it's like blowing his nose and stuff 24 hours a day; every time I see him he blowing his nose and it seems like the air is more toxic and makes it worse.”—Hispanic Female 14) “The people more affected are the kids because they go to school and are breathing contaminated air inside and outside the classroom…here we have one school, less than half a mile from the rail yard, and the number of asthma cases is increasing.”—Hispanic Female |

| Some community participants noted the difference in air quality at different times of the day and seasons. |

|

15) “I'll wake up in the mornings, like, I can't breathe.”—Hispanic Female 16) “When the weather is the hottest, that is when we have the most kids that are sick, with little kids getting sick with a horrendous cough, like a smoker's cough.”—Hispanic Female |

|

|

| Rail Yard Challenges |

|

|

| Members understand that semitrailer truck movement around the rail yard is necessary but are frustrated by spotty enforcement of truck idling laws. |

|

17) “… They're idling in their trucks and there are signs out there saying ‘do not park your vehicles there.’”—African-American Female 18) “They'll park their trucks wherever they wanna park it, and there is nothing to be said about it. You got to go to the right places and get to the right people to respond, because if you don't, they ain't gonna do nothing about it.”—African-American Male |

| Noise pollution causes sleep disturbances and other stressors, including physical “rattling and shaking” of nearby homes caused by rail yard activities. |

|

19) “I guess it was naïve of me to think that when the traffic dies down so will the noise, but there is still a lot of noise happening within the night. I know that it's affecting me and it's also affecting others in the community because they report hearing this especially when they are sleeping.”—Hispanic Female 20) “Yeah it's pretty loud. You hear it in the middle of the night, BOOM it wakes you up. I live about two blocks away and you can still hear it real loud.”—African-American Female 21) “The noise bothers me too much. I live in a mobile home and when the train passes by my house, the whole house shakes. That's where I live and it's a house that I am paying for and that is the sacrifice we are all doing.”—Hispanic Female |

| Participants felt that they have sacrificed overall quality of life for the benefit of the rail yard, and are concerned about health impacts on their families, especially their children. |

|

22) “I think we like the package from where we live, what we do not like is that the railway is so close because that affects us. My husband has symptoms of asthma, and then allergies follow. My youngest daughter also gets the flu and bronchitis. We would like for the rail yard to be more careful.”—Hispanic Female 23) “I want to say that the contamination that the train brings and the type of fuel that it uses is reflected in the kids' health; for me it is obvious that they go hand in hand.”—Hispanic Female 24) “ …because they continue to use dirty equipment, then that pollutes the air, which harms the neighbors. So all we want is really for them to be good neighbors; to be responsible.”—Hispanic Female 25) “Companies are the masters of the nation and they do not listen to our concerns because for all the calls that have been done to tell them to maintain and update their equipment it appears that we have not done the petition correctly.”—Caucasian Female |

|

|

| Health Care Challenges |

|

|

| Community participants view health and access to health care as an unattainable value for themselves, but haven't given up hope of obtaining it for their children. |

|

26) “The community worries me, but first I have to worry about my family. Many of us have no health insurance and these diseases, tumors, asthma, having to constantly go to the doctor is expensive, that worries the mom, dad, children, and the whole family.”—Hispanic Female 27) “I am a grandmother to six kids and I don't matter much, but the little ones do.”—Hispanic Female 28) “The situation with children in this community is very bad. My granddaughter was not sick so often, but since she moved and lives with me she constantly gets sick.”—Hispanic Female |

Violence and Unemployment: the Ripple Effect

Even though we discussed other community issues and challenges in the context of air pollution and concerns regarding the rail yard it is noteworthy that the high levels of violence, homelessness, and unemployment experienced by many members in this community emerged as a primary issue. At numerous points during the group discussions, the conversation turned to these topics as they clearly affected almost everyone in the community. Drug use and distribution, gang violence, and robberies were cited as daily occurrences, and the safety of family and friends was a top priority. Associated with high unemployment and prominent in the conversations were reports of increasing numbers of individuals and entire families that were homeless. Together these reports paint a picture of a struggling community plagued with violence and poverty, conditions that some participants felt would not improve. Indeed, this affected the way many residents felt about their exposure to polluted air; while they recognized it as negative, they clearly placed it further down their list of priorities compared to daily survival.

Adding to concerns about these pressing community problems was the fear that their children would become just another violence statistic. Participants said that families are increasingly headed by a single parent who must provide for the entire family, and as a result the children and youth often do not have the necessary supervision required. Many saw this as a contributing factor to an increase in youth-related crime and gang violence. Interviewees expressed a concern about the lack of alternatives and programs for young people in the community. The local community center was identified as the one remaining safe and fun place to take their kids; the lone asset. Overall, safety for themselves and their families was found to be a top priority for participants, with many expressing desperation and a general lack of control over improving the level of community violence.

Community infrastructure was cited as a contributing factor in the level of violence. Since the economic downturn, the few remaining community businesses in the area included liquor and convenience stores, auto shops, bail bondsmen, payday loan stores, and nightclubs, most of which were not viewed as supportive of a healthy lifestyle or environment by the community members. Participants also reported serious problems in the city's infrastructure, such as the lack of sidewalks, faulty or nonexistent street lights, increasing numbers of abandoned houses, empty lots with overgrown weeds, poorly maintained parks and community centers, and businesses that increasingly relocated out of the city, all of which negatively impacted their already struggling community.

As mentioned earlier we had conducted ethnographies and observed community life as part of our qualitative inquiry. When comparing the neighborhoods surrounding the rail yard with other nearby communities, a tangible difference existed in the environment. The area is eerily gray and dusty and feels abandoned despite its high population density. This, in combination with the ever-present clanging noises of the rail yard, creates a feeling of an industrial desert in which residents are somewhat hidden, quickly entering and exiting their homes that provide them some respite from the dust, heat, and noise. Many community members considered moving away from the area because of this, but the low cost of living compared to surrounding communities keeps them there. Residents felt torn between keeping their families in an area that exposes them to many health and safety hazards they can afford living in versus moving to a healthier but more costly area beyond their financial means.

Air Quality Challenges

A second emergent theme, air quality, was woven into the experiences of people living in the area already known for its poor air quality. The majority of participants reported that their adult families or friends often experience poor health and disease, but few saw a potential link between the air pollution and poor health. For children, respiratory illnesses such as asthma, allergies, and chronic cough were reported as common ongoing health problems, with many acknowledging that the surrounding environment likely affects their child's condition. Some community participants pointed out children's particular vulnerability, voicing growing concerns that poor air quality may be affecting their children's health. Even so, during the discussion about air quality, the conversation often returned to the issue of violence and safety as more urgent. Many interviewees acknowledged the air quality was not the best but felt that poor air quality was the least of their worries. They seemed resigned to their lack of control on the air quality issue, and that they are simply trying to “get by” and coexist with the problem.

Rail Yard Pros and Cons

A third emergent theme, rail yard pros and cons, was centered on interviewees' shared perceptions about life near a major rail yard. For them, the rail yard was seen as both an asset and a barrier to their ability to live a better life. Participants felt that the rail yard had a positive reputation and was highly valued for the jobs and economic growth it provides. It was also perceived, however, as a major contributor to both the surrounding poor air quality as well as the noise pollution. Several participants believed that living in such close proximity to the rail yard had caused ailments in family, friends, and neighbors, as well as themselves. Despite the fact that none of our respondents reported working, having worked, or having a relative or a friend work for the rail yard, however, none of the community members participating in our study wanted the rail yard to close or relocate. Their own experience with unemployment made them value the potential for jobs for others even if they themselves couldn't benefit. Many expressed a strong desire for the rail yard to “step up,” be a good neighbor and make reasonable changes to help protect the surrounding community from the noise and air pollution it generates. Attendees felt that the rail yard did not listen to suggestions (e.g., alternate routes, more updated equipment) from residents about ways to reduce the impact their facility has on the surrounding community. Some participants felt that they have sacrificed for the benefit of the rail yard and were concerned about the health impact of life near such a busy rail yard, especially for their children.

More noted than air pollution, a recurring comment from community members was the unrelenting noise emanating from the rail yard, where operations are conducted 24/7. Community members voiced annoyance with the noise, specifically citing the noise of trains and associated semitrailer trucks, whistles sounding in the night, and boxcars crashing up against one another. Community members reported that the noise affected their sleep, causing side effects such as tiredness and lack of concentration at school for the kids and on the job for themselves. Many also noted that in addition to the noise, the physical “rattling and shaking” has affected them as well as their homes.

In addition, the semitrailer trucks driving in and out of the rail yard to load and unload freight were seen as major contributors to rail yard pollution. Residents noted that despite posted signs for parking prohibition and idling in residential areas, trucks continue to do so near homes and the community park. They report that little to no enforcement of these posted rules occurs, a fact that was validated during our ethnographies.

Health as an Unattainable Value

Our final theme centered on the idea that our participants felt that for them personally as adults, achieving optimal personal health and gaining access to health care are for the most part out of their reach— “unattainable”—as they are far from what they can realistically expect for themselves. They have, however, not yet given up hope that their children will live a better and healthier life that includes access to routine medical services. The reality for our participants is that despite their needs for medical care, few have health insurance or the financial resources to take their children to the physician for either regular exams or when they are sick. Many parents interviewed reported that they saw their children and a large proportion of the children in the community as chronically ill, especially with respiratory illnesses, and that they saw it as inevitable that more and more will develop chronic respiratory illnesses.

Interrelationships Among the Themes

Our four emergent themes, while separate, are also clearly interwoven into a single core concept—Experiences of the rail yard community: Life is hard. The “life is hard” theme sums up the experiences of the residents who live adjacent to the rail yard. While no one raised the issue of fairness, the residents seem somewhat resigned to their situation, especially for themselves as adults; the only resistance to the status quo came when discussing their children's health. The theme of violence and unemployment was directly linked with the theme of health as an unattainable value, since many community participants reported that lack of jobs translates into a lack of health care access for themselves and their families. Adding to the challenge of not having access to health care is the fact that living in close proximity to the rail yard negatively impacts the respiratory health of children, exacerbating problems and further increasing the need for health care services, clearly a less than ideal situation for raising a healthy family.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that members residing near the rail yard live in a community that has multiple significant barriers to their quality of life, with many factors interrelated and stemming from the economic downturn. The major concerns voiced by our participants centered on the high level of community violence; serious economic problems; homelessness; rail yard–related noise exposure; and lack of access to health care, especially for their children, many of whom suffer from poor respiratory health. Public health scientists are beginning to point to the linkages between the way that goods and services are accessed and distributed across the nation and various environmental and societal impacts such as air pollution, noise, stress and anxiety, and loss of land and planning blight that can burden local communities (Mindell et al., 2011). Increasing evidence mentioned by the governor's environmental action plan, that communities near goods movement ports are subsidizing the movement of goods with their own health, highlights the need for continued intervention and policy advancement aimed at diesel exposure reduction to protect the health of the public (Hricko, 2006).

The health of this community, particularly the more vulnerable subpopulations (e.g., children and elderly), is of great concern given the environment in which they live, their lack of access to health care, and stresses related to violence. It has been well documented that neighborhood-level conditions have a strong impact on individual health status including morbidity and mortality (Cubbin, LeClere, & Smith, 2000; Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997; Schulz et al., 2000). Additionally, research suggests that disadvantaged populations who suffer from chronic stressors experience even greater susceptibility to environmental hazards (Gee & Payne-Sturges, 2004). In our target community, 27.6% of residents live below the poverty line and FBI crime statistics report a per capita violent crime rate nearly 2.5 times the national average. This “double jeopardy” of life stress and pollution-related stressors points to an even greater potential vulnerability for this underserved and overlooked community.

Researchers have identified a strong association between ambient air pollution and other sociodemographically related stressors and adverse health outcomes. Clougherty and co-authors (2007) have reported the synergistic effect of traffic-related air pollution and exposure to violence on urban asthma etiology. Chen and co-authors (2008) have reported that chronic trafficrelated air pollution and stress interact to predict biologic and clinical outcomes in asthma that are stronger than either factor alone. Research conducted in Southern California indicates that children from stressful households are more susceptible to the negative effects of traffic-related air pollution on respiratory health (Islam et al., 2011; Shankardass et al., 2009). Clearly, living in an area in which the adverse health effects associated with air pollution are magnified in the presence of other non-pollution-related stressors highlights a critical need for routine medical services and additional support for positive community change.

In our inquiry it became clear that many of the community members felt overwhelmed with the day-to-day challenges of simply surviving and providing for their families in this challenged community; everyday challenges often outweighed their concern about the poor air quality that all acknowledged as existing. Indeed, a few times during the focus groups some members were irritated with the discussion of air quality and suggested focusing on more pressing issues. Only a small number of participants were vocal about the health effects associated with air pollution while many others had resigned themselves to coexisting with the poor air quality. The internal pressures of day-to-day living for a person can greatly influence their perception of the surrounding community environment and their subsequent behavior, especially given the severity of the daily burdens just to survive (Balcetis & Dunning, 2007). In light of the daily challenges faced by the residents, it is not difficult to understand why air quality might rank lower on their list of priorities.

One notable exception was the parents' deep concern for the health of their children. Some awareness existed that the number of asthma cases are increasing and many believed that most children in the area either already have asthma or will develop it in the future. Only a few parents, however, connected increased asthma incidence with exposure to pollution from the nearby rail yard. As this line of discussion continued, it became apparent that some parents were angry that air pollution from the rail yard may be jeopardizing their children's health or the health of children in their community. They found it deeply upsetting that rail yard–related air pollution may not only increase their child's risk of developing asthma, but may exacerbate the asthma symptoms of children already diagnosed with the condition, in essence increasing the need for medical services that many families already find difficult or impossible to access. During the discussions it became evident that their children's health was a unifying issue for the community and potential mobilization point.

Implications for Change

In addition to the participant feedback about their experiences we were also able to identify suggestions for improvements for this dire situation that involved things that could be done by the rail yard and by other local agencies, businesses, institutions, and medical centers. The suggestions focused on improvements that included increased access to medical services and routine health screenings, development of a more extensive vegetation barrier and community-wide tree planting campaign, relocation of the entry gate to the rail yard to remove truck traffic and related idling, and provision of safe and pollution “freer” places for children to play in. Other efforts discussed included bringing upgraded air filters to local schools and implementation of community noise and pollution reduction programs. Table 3 describes the suggested changes for the area in promoting a healthier community. A report by the National Environmental Justice Advisory Council (NEJAC) to the U.S. EPA titled, “Reducing Air Emissions Associated With Goods Movement: Working Towards Environmental Justice” contains advice and recommendations about how U.S. EPA can most effectively promote strategies in partnership with federal, state, tribal, and local government agencies and other stakeholders to identify, mitigate, or prevent the disproportionate burden on communities of air pollution resulting from goods movement (NEJAC, 2009). The NEJAC report encourages a sense of urgency in developing strategies and taking action and advocates for additional research with strong community involvement and community capacity building. For this underserved community an immediate and great need exists for sustainable community improvements that address the air quality issues but also consideration for the other pressing needs identified by community participants as well (Bell & Standish, 2005).

Table 3. Community Challenges and Suggestions for Positive Change.

| Community Challenge | Suggestions for Improvement |

|---|---|

| Noise |

|

| Poor air quality |

|

| Lack of health services |

|

| Violence |

|

The health and environmental challenges faced by this community are most likely a common phenomenon faced by communities in close proximity to major goods movement facilities across the nation. Given the gravity of the situation and their challenges, the needs of this community and similar communities should be addressed by policy leaders and advocates taking a Health in All Policies Approach (HiAP). According to the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), HiAP is a change in the systems that determine how policy decisions are developed and implemented to ensure that policy decisions do not negatively impact determinants of health, but rather strive for beneficial effects (NACCHO, 2013). HiAP is an innovative and strategic approach through which policies are created and implemented, emphasizing the need for input and collaboration across industry and sectors to ultimately achieve common health goals. The enormity and complexity of the desperate conditions faced by the community residents call for the use of a HiAP approach in addressing their health and environmental challenges. Only through a coordinated effort from numerous surrounding key government, business, and institutional agencies will positive improvements be implemented and sustained. Linking community planning to goals of increasing population health and decreasing exposure to harmful risk factors can be successfully implemented and sustained (Morland, Wing, Diez Roux, & Poole, 2002; Pucher & Dijkstra, 2003). A combined approach focusing on the goods movement communities and prevention that addresses the multitude of factors determining their health will get at the heart of the problem that is drastically and negatively influencing the health trajectory of the community members (Bell & Standish, 2005).

Limitations

Given the qualitative nature of our study, some noteworthy limitations are present. The information we gained is the opinions of a sample of our target community and may not represent the views of all community members. We conducted systematic, theoretical sampling to recruit participants from each community stratum to accurately represent community demographics, however. As a result we managed to recruit an ethnically diverse group of community participants, from varying educational backgrounds and work profiles, including the unemployed and homeless.

Conclusion

Our inquiry was successful in providing important insights into the life of community members who live adjacent to a rail yard that has been identified as a major source of pollution. Our findings suggest that future efforts to reduce exposure to air pollution must take into consideration other major community challenges, including increased access to health care and a reduction in community violence. Most importantly a need exists for a coordinated effort of governmental and private entities to strategically address these challenges and provide support for this truly underserved and isolated community. A systematic approach should be taken by policy leaders and advocates with policy development grounded in a HiAP addressing communities across the nation that are impacted by the goods movement industry. As we all are the beneficiaries of inexpensive goods shipped through this and other container yards, we have an ethical obligation to support positive community improvements for those who carry an undue health burden as a side effect of our access to inexpensive goods.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the South Coast Air Quality Management District/BP West Coast Products Oversight Committee, LLC, grant # 659005 and also supported by National Institutes of Health #1P20MD006988.

Contributor Information

Rhonda Spencer-Hwang, School of Public Health, Loma Linda University.

Susanne Montgomery, School of Behavioral Health, Loma Linda University.

Molly Dougherty, School of Public Health, Loma Linda University.

Johanny Valladares, School of Public Health, Loma Linda University.

Sany Rangel, School of Public Health, Loma Linda University.

Peter Gleason, School of Public Health, Loma Linda University.

Sam Soret, School of Public Health, Loma Linda University.

References

- Attfield MD, Schleiff PL, Lubin JH, Blair A, Stewart PA, Vermeulen R, Coble JB, Silverman DT. The diesel exhaust in miners study: A cohort mortality study with emphasis on lung cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104(11):869–883. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcetis E, Dunning D. Cognitive dissonance and the perception of natural environments. Psychological Science. 2007;18(10):917–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J, Standish M. Communities and health policy: A pathway for change. Health Affairs. 2005;24(2):339–342. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer M, Hoek G, Smit HA, de Jongste JC, Gerritsen J, Postma DS, Kerkhof M, Brunekreef B. Air pollution and development of asthma, allergy, and infections in a birth cohort. The European Respiratory Journal. 2007;29(5):879–888. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00083406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer M, Lencar C, Tamburic L, Koehoorn M, Demers P, Karr C. A cohort study of traffic-related air pollution impacts on birth outcomes. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008;116(5):680–686. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Air Resources Board. Public health impacts Draft emission reduction plan for ports and international goods movement. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.arb.ca.gov/planning/gmerp/dec1plan/chapter3.pdf.

- California Air Resources Board. Health risk assessment for the BNSF San Bernardino railyard. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.arb.ca.gov/railyard/hra/bnsf_sb_final.pdf.

- Chen E, Schreier HM, Strunk RC, Brauer M. Chronic traffic-related air pollution and stress interact to predict biologic and clinical outcomes in asthma. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008;116(7):970–975. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clougherty JE, Levy JI, Kubzansky LD, Ryan PB, Suglia SF, Canner MJ, Wright RJ. Synergistic effects of traffic-related air pollution and exposure to violence on urban asthma etiology. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007;115(8):1140–1146. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubbin C, LeClere FB, Smith GS. Socioeconomic status and injury mortality: Individual and neighbourhood determinants. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2000;54(7):517–524. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.7.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan G, Prestemon J. The effect of trees on crime in Portland, Oregon. Environment and Behavior. 2010;44(1):3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Walters S, Griffiths RK. Hospital admissions for asthma in preschool children: Relationship to major roads in Birmingham, United Kingdom. Archives of Environmental Health. 1994;49(4):223–227. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1994.9937471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Zhiyi B, Zhujun Z, Jiani L. The investigation of noise attenuation by plants and the corresponding noise-reducing spectrum. Journal of Environmental Health. 2010;72(8):8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauderman WJ, Vora H, McConnell R, Berhane K, Gilliland F, Thomas D, Lurmann F, Avol E, Kunzli N, Jerrett M, Peters J. Effect of exposure to traffic on lung development from 10 to 18 years of age: A cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369(9561):571–577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Payne-Sturges DC. Environmental health disparities: A framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2004;112(17):1645–1653. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruzieva O, Bergström A, Hulchiy O, Kull I, Lind T, Melén E, Moskalenko V, Pershagen G, Bellander T. Exposure to air pollution from traffic and childhood asthma until 12 years of age. Epidemiology. 2013;24(1):54–61. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318276c1ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C, Zurakowski D, Bennet J, Walker-White R, Osman JL, Quarles A, Oriol N. Knowledgeable neighbors: A mobile clinic model for disease prevention and screening in underserved communities. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(3):406–410. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann B, Moebus S, Kröger K, Stang A, Möhlenkamp S, Dragano N, Schmermund A, Memmesheimer M, Erbel R, Jöckel KH. Residential exposure to urban air pollution, ankle-brachial index, and peripheral arterial disease. Epidemiology. 2009;20(2):280–288. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181961ac2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hricko A. Global trade comes home: Community impacts of goods movement. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008;116(2):A78–81. doi: 10.1289/ehp.116-a78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hricko AM. Ships, trucks, and trains: Effects of goods movement on environmental health. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2006;114(4):A204–205. doi: 10.1289/ehp.114-a204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam T, Urman R, Gauderman WJ, Milam J, Lurmann F, Shankardass K, Avol E, Gilliland F, McConnell R. Parental stress increases the detrimental effect of traffic exposure on children's lung function. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2011;184(7):822–827. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0720OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Satcher D. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Ma R, Pope CA, 3rd, Krewski D, Newbold KB, Thurston G, Shi Y, Finkelstein N, Calle EE, Thun MJ. Spatial analysis of air pollution and mortality in Los Angeles. Epidemiology. 2005;16(6):727–736. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181630.15826.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo FE, Sullivan WC. Environment and crime in the inner city: Does vegetation reduce crime? Environment and Behavior. 2001;33(3):343–367. [Google Scholar]

- Mack T. Cancers in the urban environment. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel J. Clamoring for quiet: New ways to mitigate noise. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005;113(1):A46–49. doi: 10.1289/ehp.113-a46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis HG, Mann JK, Lurmann FW, Mortimer KM, Balmes JR, Hammond SK, Tager IB. Altered pulmonary function in children with asthma associated with highway traffic near residence. International Journal of Environmental Health Research. 2009;19(2):139–155. doi: 10.1080/09603120802415792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JS, Watkins SJ, Cohen JM, editors. Health on the move 2 Policies for health promoting transport. Stockport, UK: Transport and Health Study Group; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Morani A, Nowak DJ, Hirabayashib S, Calfapietraa C. How to select the best tree planting locations to enhance air pollution removal in the MillionTreesNYC initiative. Environmental Pollution. 2011;159(5):1040–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of County and City Health Officials. Health in all policies. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.naccho.org/topics/environmental/HiAP/

- National Environmental Justice Advisory Council. Reducing air emissions associated with goods movement: Working towards environmental justice. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/resources/publications/nejac/2009-goods-movement.pdf.

- Newcomb P, Li J. Predicting admissions for childhood asthma based on proximity to major roadways. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2008;40(4):319–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak D. Tree species selection, design, and management to improve air quality. 2000 Retrieved from http://www.fs.fed.us/ccrc/topics/urban-forests/docs/Nowak_Trees%20for%20air%20quality.pdf.

- Nowak D, Crane D, Stevens JC. Air pollution removal by urban trees and shrubs in the United States. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2006;4:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Onder S, Kockbeker Z. Importance of the green belts to reduce noise pollution and determination of roadside noise reduction effectiveness of bushes in Konya, Turkey. World Academy of Science, Engineering, and Technology. 2012;66(6):11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Painter K, Farrington D. Evaluating situational crime prevention using a young people's survey: Part II making sense of the elite police voice. The British Journal of Criminology. 2001;41(2):266–284. [Google Scholar]

- Perez L, Künzli N, Avol E, Hricko AM, Lurmann F, Nicholas E, Gilliland F, Peters J, McConnell R. Global goods movement and the local burden of childhood asthma in southern California. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl. 3):S622–628. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucher J, Dijkstra L. Promoting safe walking and cycling to improve public health: Lessons from The Netherlands and Germany. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(9):1509–1516. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe JJ, Thompson CW, Aspinall PA, Brewer MJ, Duff EI, Miller D, Mitchell R, Clow A. Green space and stress: Evidence from cortisol measures in deprived urban communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013;10(9):4086–4103. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10094086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salam MT, Islam T, Gilliland FD. Recent evidence for adverse effects of residential proximity to traffic sources on asthma. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2008;14(1):3–8. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3282f1987a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz ES, Gruzieva O, Bellander T, Bottai M, Hallberg J, Kull I, Svartengren M, Melén E, Pershagen G. Traffic-related air pollution and lung function in children at 8 years of age: A birth cohort study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012;186(12):1286–1291. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1045OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz A, Williams D, Israel B, Becker A, Parker E, James SA, Jackson J. Unfair treatment, neighborhood effects, and mental health in the Detroit metropolitan area. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(3):314–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankardass K, McConnell R, Jerrett M, Milam J, Richardson J, Berhane K. Parental stress increases the effect of traffic-related air pollution on childhood asthma incidence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(30):12406–12411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812910106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman DT, Samanic CM, Lubin JH, Blair AE, Stewart PA, Vermeulen R, Coble JB, Rothman N, Schleiff PL, Travis WD, Ziegler RG, Wacholder S, Attfield MD. The diesel exhaust in miners study: A nested case-control study of lung cancer and diesel exhaust. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104(11):855–868. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spira-Cohen A, Chen LC, Kendall M, Lall R, Thurston GD. Personal exposures to traffic-related air pollution and acute respiratory health among Bronx schoolchildren with asthma. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119(4):559–565. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2010 Census. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/2010census/data/