Abstract

Amniotic epithelial cells (AEC) derived from human placenta represent a useful and noncontroversial source for liver-based regenerative medicine. Previous studies suggested that human- and rat-derived AEC differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells upon transplantation. In the retrorsine (RS) model of liver repopulation, clusters of donor-derived cells engrafted in the recipient liver and, importantly, showed characteristics of mature hepatocytes. The aim of the current study was to investigate the possible involvement of cell fusion in the emergence of hepatocyte clusters displaying a donor-specific phenotype. To this end, 4-week-old GFP+/DPP-IV− rats were treated with RS and then transplanted with undifferentiated AEC isolated from the placenta of DPP-IV+ pregnant rats at 16–19 days of gestational age. Results indicated that clusters of donor-derived cells were dipeptidyl peptidase type IV (DPP-IV) positive, but did not express the green fluorescent protein (GFP), suggesting that rat amniotic epithelial cells (rAEC) did not fuse within the host parenchyma, as no colocalization of the two tags was observed. Moreover, rAEC-derived clusters expressed markers of mature hepatocytes (eg, albumin, cytochrome P450), but were negative for the expression of biliary/progenitor markers (eg, epithelial cell adhesion molecule [EpCAM]) and did not express the marker of preneoplastic hepatic nodules glutathione S-transferase P (GST-P). These results extend our previous findings on the potential of AEC to differentiate into mature hepatocytes and suggest that this process can occur in the absence of cell fusion with host-derived cells. These studies support the hypothesis that amnion-derived epithelial cells can be an effective cell source for the correction of liver disease.

Introduction

In recent years, stem-cell research has demonstrated that embryonic, adult, or induced pluripotent stem cells possess great plasticity and are regarded as potent tools for regenerative medicine in the near future. Several stem cell types have been reported to differentiate in vivo toward the cell type of the tissue in which they engraft [1–4]. However, it has been shown that cell fusion between donor cells and the host tissue is a rare, but possible, mechanism by which a mature tissue phenotype can be generated [5–7]. As a result, cell fusion may be mistaken for stem cell plasticity and differentiation.

The use of stem cells in regenerative medicine of the liver has been proposed as a possible source for isolated hepatocyte transplantation [8–10].

We recently reported that amniotic epithelial cells (AEC) derived from human placenta retain stem cell characteristics, can differentiate into hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo, and were able to correct a mouse model of maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) [11–14]. Moreover, syngeneic rat-derived AEC differentiated into hepatocyte-like cells upon transplantation in the Retrorsine (RS) model of liver repopulation. Clusters of donor-derived cells engrafted in the recipient liver. However, the possibility that transplanted cells fused with cells in the host parenchyma was not assessed. The aim of the current study was to investigate the possible involvement of cell fusion in the emergence of hepatocyte clusters displaying a donor-specific phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Animals and treatments

All animals were maintained on daily cycles of alternating 12-h light–12-h darkness with food and water available ad libitum. They were fed a Purina Rodent Lab Chow diet throughout the experiment and received humane care according to the criteria outlined in the National Institutes of Health Publication 86-23, revised 1985. Animal studies were reviewed and approved by the University of Cagliari Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation.

Fischer 344 rats carrying an enhanced green fluorescent protein transgene under the control of a ubiquitin C promoter were provided by the Rat Resource and Research Center, University of Missouri (Columbia, MO). Homozygous rats from this strain (hereafter referred as GFP+) were crossed with DPP-IV-deficient syngeneic rats, available at the animal facility of our University. Heterozygous F1 generation was intercrossed and about 11% of F2 was GFP+/DPP-IVnull. Homozygosis of GFP was assessed by polymerase chain reaction as instructed by the provider. DPP-IV deficiency was assessed by histochemical detection of the enzyme on a tail snip [15]. F3 GFP+/DPP-IVnull progeny was used as a recipient. Four-week-old rats were given two intraperitoneal injections of 30 mg/kg RS (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 2 weeks apart.

rAEC isolation and transplantation

Donor rat amniotic epithelial cells (rAEC) were isolated from the placentae of syngeneic GFP−/DPP-IV+ pregnant rats at 16–19 days of gestational age as previously described [16]. Briefly, the yolk-sac membrane was carefully peeled and the inner white avascular membrane (amniotic membrane) was collected. After a quick wash in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), amniotic membranes were digested in Trypsin/EDTA 0.05% (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C for 20–30 min. The cell suspension was passed through a 100-μm strainer, centrifuged, and resuspended in PBS. The cell viability was assessed by Trypan Blue dye exclusion and consistently exceeded 98%. One month after RS treatment, recipient animals received 2/3 partial hepatectomy and 1.5×106 freshly isolated rAEC were injected through a mesenteric vein. Animals were sacrificed 8 months after cell transplant.

Immunofluorescence analyses

To preserve the native GFP, fresh liver tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose solution for 24 h at 4°C, and then frozen. To detect the DPP-IV enzyme (also referred as CD26 surface antigen), 5-μm-thick PFA/Sucrose sections were blocked for 30′ with goat serum and incubated for 1 h at RT with anti-CD26 antibody (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA). Sections were then incubated with Alexa 555-conjugated secondary anti-mouse IgG (Life Technologies) for 30′ at RT. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Double immunofluorescence staining for CD26 and albumin, cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2E1 and 3A1, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF 4α), β-catenin, cytokeratin 7 (CK 7), EpCAM, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) (all from Abcam), connexin 32 (Life Technologies), oval cell marker 6 (OV6) (Santa Cruz), and glutathione S-transferase P (GST-P) (LifeSpan Biosciences, Seattle, WA) was performed on 5-μm-thick sections from snap-frozen liver tissues, where the native GFP is lost. Briefly, slides were fixed in cold acetone for 10′, blocked for 30′ with goat serum, and incubated for 1 h at RT (or overnight at 4°C for albumin) with the primary antibody of interest. Sections were then washed and incubated with Atto 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (Abcam) for 30′ at RT (except for albumin, which was an FITC-conjugated antibody). After wash, slides were further incubated for CD26 staining as described above. All slides were examined with an IX71 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

rAEC engraft and form clusters of DPP-IV+/GFP− cells indicating that no fusion occurred

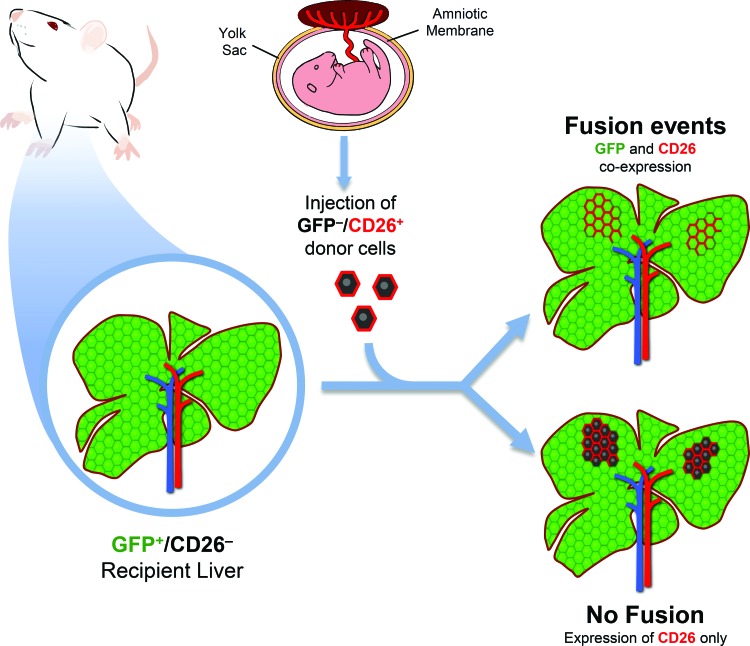

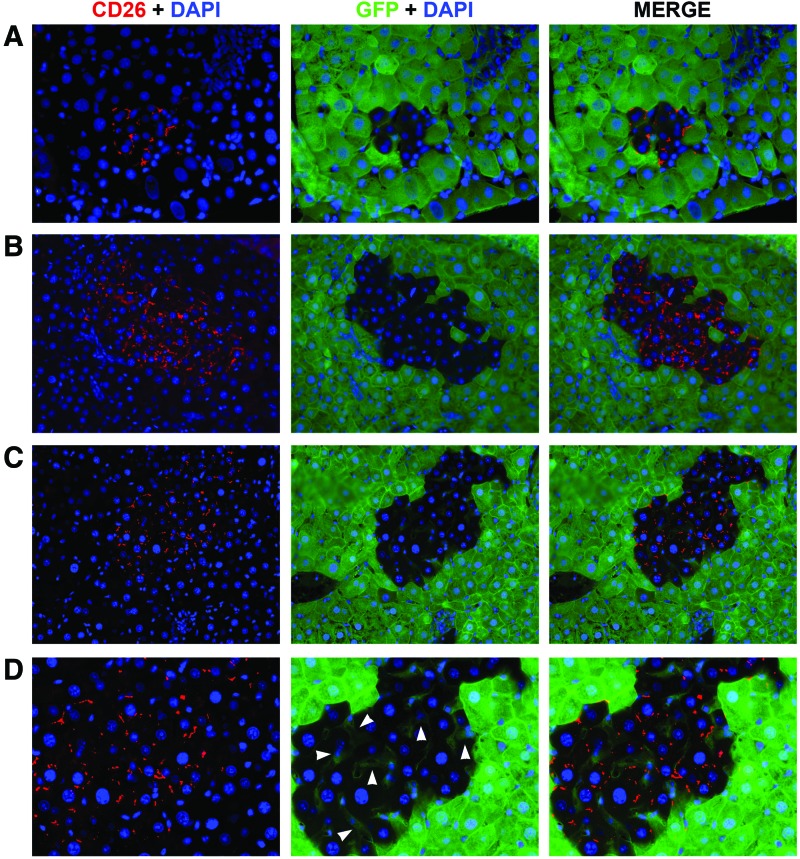

To determine if fusion events occurred, we utilized a transplantation model in which recipient animals ubiquitously expressed GFP and were deficient for the expression of DPP-IV (hereafter referred as CD26). On the contrary, donor rAEC were isolated from CD26-expressing pregnant rats that did not express GFP. Both gene products are expressed by a dominant allele, so that heterozygous animals are also phenotypically positive. Therefore, as depicted in Figure 1, in the presence of fusion events, fused cells would share genetic information and coexpress GFP (from the recipient cell) and CD26 (from the donor cell). On the other hand, in the absence of cell fusion, clusters of donor-derived cells would retain their original phenotype, thus expressing only CD26. Eight months after cell transplant, PFA/sucrose sections were analyzed (Fig. 2). Immunofluorescence staining for CD26 showed that clusters of donor-derived origin were present in the recipient liver, thus confirming that syngeneic rAEC were able to engraft and replicate. Moreover, all the observed clusters were devoid of GFP expression with no signs of colocalization with the CD26 antigen (Fig. 2A–C). This suggests that rAEC did not fuse with cells in the host parenchyma.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the experimental design. Recipient animals ubiquitously expressed green fluorescent protein (GFP) and were deficient for the expression of CD26. Donor amniotic epithelial cells (AECs) were isolated from CD26-expressing rats that did not express GFP. In the presence of fusion events, fused cells would share genetic information and coexpress GFP and CD26, whereas in the absence of cell fusion, clusters of donor-derived cells would only express CD26. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

FIG. 2.

Rat amniotic epithelial cells (rAEC) engraft in the host liver and do not fuse with recipient cells. (A–C) Immunofluorescence images of three representative clusters: donor-derived cells expressed CD26 (left column) and no colocalization with GFP (center column) was observed, whereas the recipient liver surrounding the cluster only showed GFP expression (200× magnification). Right column shows merged images. (D) Magnification of cell clusters shown in C: arrowheads indicate GFP+/CD26− sinusoidal cells of recipient origin within the clusters (400×). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

rAEC replace resident hepatocytes and acquire a mature hepatocyte phenotype

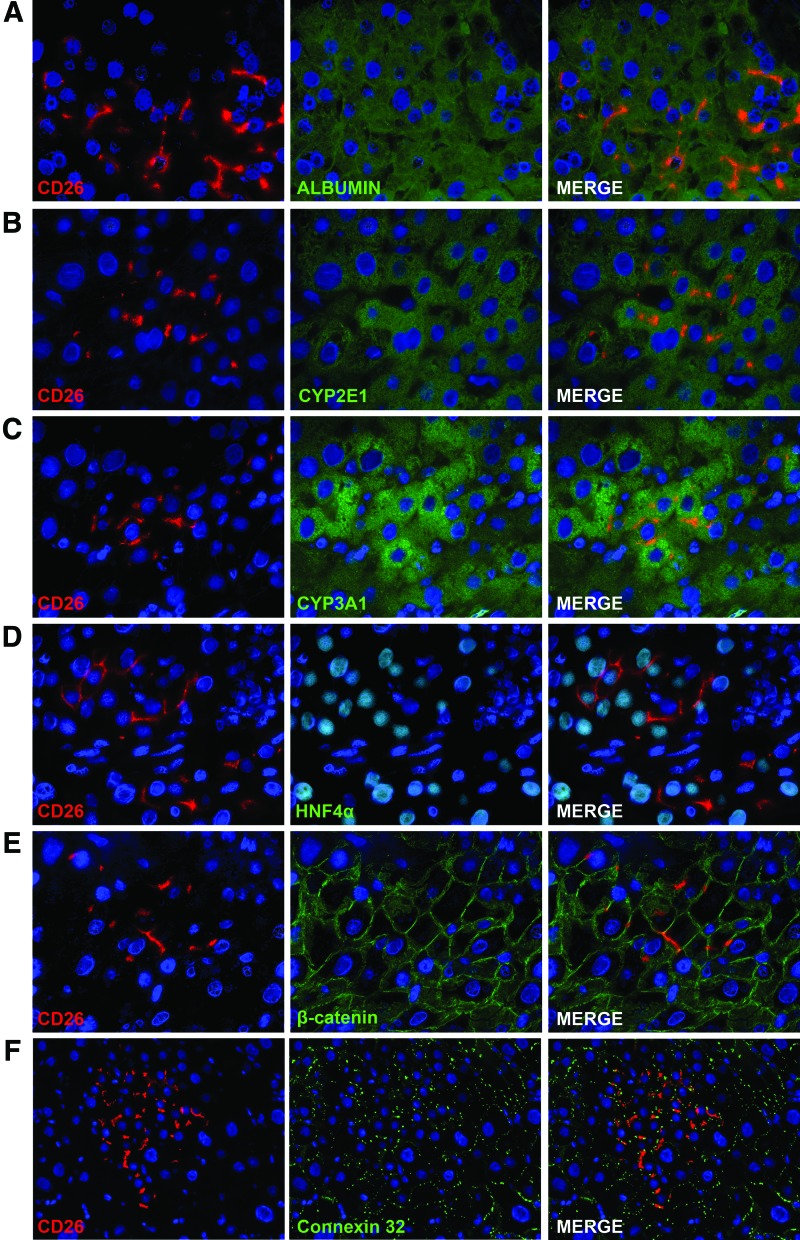

The CD26 protein in normal polarized hepatocytes is localized at the bile canaliculi between two hepatocytes [17]. In other liver cell types, such as sinusoidal cells and cholangiocytes, CD26 staining is normally faint and diffuses in the cytoplasm (data not shown). The expression pattern of CD26 in rAEC-derived clusters was spotted and localized to the membrane as observed in mature hepatocytes (Fig. 2). Interestingly, sinusoidal cells within the clusters were of recipient origin as determined by the sole expression of GFP and no cytoplasmic expression of CD26 (Fig. 2D arrowheads), thus suggesting that transplanted rAEC only differentiate into hepatocytes under the present experimental conditions. To further evaluate the phenotype of rAEC-derived clusters, frozen liver sections were stained with a panel of markers of mature hepatocytes (Fig. 3). Transplanted cells expressed albumin, two major isoforms of the cytochrome P450 family in the rat, CYP 2E1 and 3A1, HNF 4α, β-catenin, and connexin 32. The levels of expression of these markers were comparable to the surrounding liver, suggesting that rAEC were functionally integrated and acquired the phenotype of mature hepatocytes.

FIG. 3.

rAEC acquire a mature hepatocyte phenotype. Immunofluorescence staining of donor-derived clusters expressing CD26 (left column) and different markers of mature hepatocytes (center column): right column shows merged images. (A) albumin; (B) CYP 2E1; (C) CYP 3A1; (D) hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF 4α); (E) β-catenin; (F) connexin 32. (A–E 600×; F 400×). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

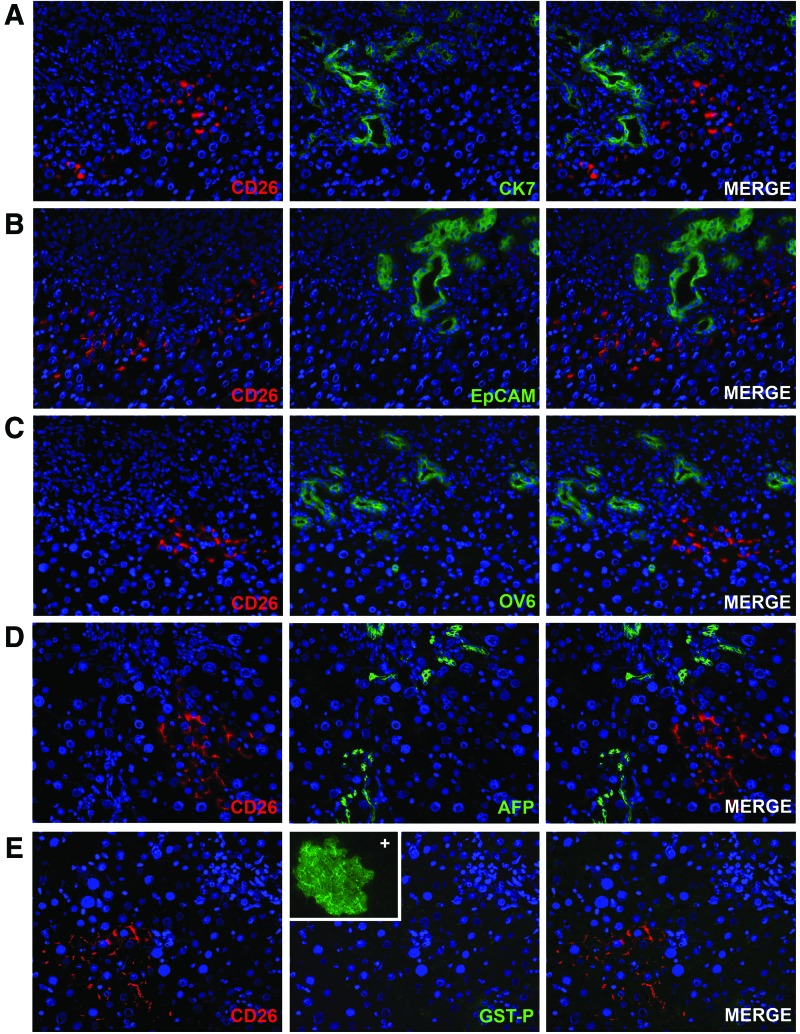

rAEC do not express markers of biliary/progenitor cells and do not display a preneoplastic phenotype

When liver damage is extensive and mature hepatocyte replication is inhibited, the parabiliary area has been reported to give rise to bipotential progenitor cells (also called oval cells) that can give rise to both biliary cells and hepatocytes [18,19]. In particular, EpCAM-positive oval cells have been reported to be bipotential adult hepatic epithelial progenitors [20]. We assessed the possibility that transplanted rAEC express biliary or progenitor markers together with the hepatocyte markers, thus displaying a mixed phenotype, resembling that of hepatic progenitors rather than mature hepatocytes. To this end, frozen liver sections were stained for markers expressed by both mature biliary cells and bipotent progenitor cells (Fig. 4A–C) [21]. rAEC-derived clusters were negative for the expression of CK 7, EpCAM, OV6, and AFP, reinforcing the hypothesis that they differentiate to fully mature hepatocytes. Moreover, the expression of GST-P, a marker of early hepatic neoplastic lesions, was evaluated in rAEC-derived clusters (Fig. 4D). No positive staining was found throughout the liver tissue (inset shows positive control slide), excluding the possibility that differentiating/replicating rAEC have acquired a preneoplastic phenotype.

FIG. 4.

rAEC do not express markers of biliary/progenitor cells and do not display a preneoplastic phenotype. (A–C) Immunofluorescence staining of liver section with donor-derived clusters expressing CD26 (left column) and bile ducts expressing biliary/progenitor markers (center column): right column shows merged images. (A) cytokeratin 7 (CK 7); (B) epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM); (C) OV6; (D) alpha-fetoprotein (AFP); (E) immunofluorescence image of donor-derived clusters expressing CD26 (left) and negative for the expression of glutathione S-transferase P (GST-P) marker of preneoplastic nodules; inset shows a nodule positive for GST-P in a control slide (200×). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Discussion

Although rat and human placentae are anatomically different, amniotic membrane-derived cells share morphological and molecular characteristics [16,22,23]. In this study, we extended our previous results on the hepatic differentiation of rat-derived AEC [11]. We reported evidence of differentiation of human amniotic epithelial cells (hAEC) toward functional hepatocytes. In vitro differentiated cells expressed mature hepatocyte marker genes and activities, including some of the major metabolizing enzymes, such as CYP 3A4, 3A7, 1A1, 1A2, 2B6, 2D6, and uridine diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1. Following in vitro differentiation, the level of expression of most liver genes was more similar to fetal rather than adult hepatocytes. On the contrary, in vivo studies showed that upon transplantation into a severe combined immunodeficient mouse, pretreated with RS, naive hAEC differentiate to cells with characteristics of mature adult hepatocytes. Moreover, we recently reported that undifferentiated hAEC transplantation was effective for the correction of the serum amino acid and brain neurochemical imbalances normally observed in a mouse model of MSUD [12,13], providing additional evidence that, when transplanted into the liver, naive hAEC express mature liver genes at levels sufficient to correct a metabolic liver disease. To detect transplanted cells in the host liver and rule out the possibility of rejection by the immune system, a similar experiment was conducted with the use of undifferentiated rAEC that were injected into a syngeneic recipient rat pretreated with RS. Clusters of donor-derived cells showing characteristics of mature hepatocytes were present in the recipient liver [11]. However, these earlier studies did not rule out the possibility of fusion between transplanted AEC and host hepatocytes.

Other stem cell types, including bone marrow-derived cells (BMC), were initially reported to differentiate into hepatocytes and other tissue-specific cells upon transplantation [1–4]. However, later and more definitive studies confirmed that BMC acquire the phenotype of other cell types through cell fusion, rather than transdifferentiation [5–7].

Therefore, it is important to determine if the mature phenotype observed following the transplantation of AEC into the liver is the result of cell fusion or cell differentiation.

In the present study, we showed that AEC isolated from rat placenta were able to engraft and were maintained up to 8 months after transplantation. Donor-derived cells replicated in the host liver without evidence of cell fusion. Morphological and molecular analyses suggested that clusters originating from rAEC contained mature hepatocytes. Under the present experimental conditions, transplanted rAEC only differentiated into hepatocytes, while sinusoidal cells within the clusters were of recipient origin. Appropriate integration into the host liver parenchyma was confirmed by the expression of CD26 that was localized in polarized cells at the bile canaliculi between two adjacent hepatocytes. Moreover, connexin 32, the predominant gap junction protein that mediates communication between adjacent hepatocytes in the liver, was normally expressed by transplanted cells. Furthermore, immunofluorescence analysis of donor-derived clusters revealed that transplanted cells expressed other protein characteristics of mature hepatocytes, including albumin, CYP 2E1 and 3A1, HNF 4α, and β-catenin, at levels comparable to those observed in the surrounding liver. We also examined the possibility that rAEC displayed characteristics attributed to so-called hepatic progenitors. However, donor-derived clusters did not express CK 7, EpCAM, OV6, and AFP, which are normally expressed by biliary/progenitor liver cells. Moreover, transplanted cells did not express GST-P, suggesting that rAEC do not acquire a preneoplastic phenotype during differentiation or replication in vivo.

Previous studies indicated that hAEC transplants corrected the biochemical and neurological imbalances normally observed in two relevant mouse models of human metabolic liver diseases and completely reversed the lethal effects of galactosamine in a mouse model of acute liver failure [8]. The present results extend our previous findings on the potential use of AEC as a source of cells for liver-based regenerative medicine. The presence of donor-derived hepatocytes in the host parenchyma in the absence of cell fusion represents conclusive evidence that AEC have the ability to differentiate to mature hepatocytes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Sardinian Regional Government (RAS). S.C.S. was supported by Torsten och Ragnar Söderberg Stiftelse and Ventenskaprådet (Swedish Research Council). We thank Anna Saba, Giovanna Porqueddu, and Roberto Marras for their excellent technical and secretarial assistance.

Part of this study was presented at “The International Liver Congress™ 2014—49th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver” April 9–13, 2014.

Author Disclosure Statement

SCS owns stock in Stemnion LLC. No cells or products from Stemnion LLC were used in these studies.

References

- 1.Lagasse E, Connors H, Al-Dhalimy M, Reitsma M, Dohse M, Osborne L, Wang X, Finegold M, Weissman IL. and Grompe M. (2000). Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo. Nat Med 6:1229–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson KA, Majka SM, Wang H, Pocius J, Hartley CJ, Majesky MW, Entman ML, Michael LH, Hirschi KK. and Goodell MA. (2001). Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. J Clin Investig 107:1395–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, Neutzel S. and Sharkis SJ. (2001). Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell 105:369–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamoto R, Yajima T, Yamazaki M, Kanai T, Mukai M, Okamoto S, Ikeda Y, Hibi T, Inazawa J. and Watanabe M. (2002). Damaged epithelia regenerated by bone marrow-derived cells in the human gastrointestinal tract. Nat Med 8:1011–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Willenbring H, Akkari Y, Torimaru Y, Foster M, Al-Dhalimy M, Lagasse E, Finegold M, Olson S. and Grompe M. (2003). Cell fusion is the principal source of bone-marrow-derived hepatocytes. Nature 422:897–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vassilopoulos G, Wang PR. and Russell DW. (2003). Transplanted bone marrow regenerates liver by cell fusion. Nature 422:901–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terada N, Hamazaki T, Oka M, Hoki M, Mastalerz DM, Nakano Y, Meyer EM, Morel L, Petersen BE. and Scott EW. (2002). Bone marrow cells adopt the phenotype of other cells by spontaneous cell fusion. Nature 416:542–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strom SC, Skvorak K, Gramignoli R, Marongiu F. and Miki T. (2013). Translation of amnion stem cells to the clinic. Stem Cells Dev 22:96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox IJ, Daley GQ, Goldman SA, Huard J, Kamp TJ. and Trucco M. (2014). Stem cell therapy. Use of differentiated pluripotent stem cells as replacement therapy for treating disease. Science 345:1247391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marongiu F, Serra MP, Sini M, Laconi E, Hansel MC, Skvorak KJ, Gramignoli R. and Strom. SC. (2013). Advances and possible applications of human amnion for the management of liver disease. In: Perinatal Stem Cells. Cetrulo KJ, Cetrulo CL, Taghizadeh RR, eds. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York City, NY, pp. 197–208 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marongiu F, Gramignoli R, Dorko K, Miki T, Ranade AR, Paola Serra M, Doratiotto S, Sini M, Sharma S, et al. (2011). Hepatic differentiation of amniotic epithelial cells. Hepatology 53:1719–1729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skvorak KJ, Dorko K, Marongiu F, Tahan V, Hansel MC, Gramignoli R, Arning E, Bottiglieri T, Gibson KM. and Strom SC. (2013). Improved amino acid, bioenergetic metabolite and neurotransmitter profiles following human amnion epithelial cell transplant in intermediate maple syrup urine disease mice. Mol Genet Metab 109:132–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skvorak KJ, Dorko K, Marongiu F, Tahan V, Hansel MC, Gramignoli R, Gibson KM. and Strom SC. (2013). Placental stem cell correction of murine intermediate maple syrup urine disease. Hepatology 57:1017–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miki T, Lehmann T, Cai H, Stolz DB. and Strom SC. (2005). Stem cell characteristics of amniotic epithelial cells. Stem Cells 23:1549–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laconi S, Pani P, Pillai S, Pasciu D, Sarma DS. and Laconi E. (2001). A growth-constrained environment drives tumor progression invivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:7806–7811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajima T, Enosawa S, Mitani T, Li XK, Suzuki S, Amemiya H, Koiwai O. and Sakuragawa N. (2001). Cytological examination of rat amniotic epithelial cells and cell transplantation to the liver. Cell Transplant 10:423–427 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stecca BA, Nardo B, Chieco P, Mazziotti A, Bolondi L. and Cavallari A. (1997). Aberrant dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV/CD26) expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 27:337–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorrell C. and Grompe M. (2005). Liver repair by intra- and extrahepatic progenitors. Stem Cell Rev 1:61–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newsome PN, Hussain MA. and Theise ND. (2004). Hepatic oval cells: helping redefine a paradigm in stem cell biology. Curr Top Dev Biol 61:1–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yovchev MI, Grozdanov PN, Zhou H, Racherla H, Guha C. and Dabeva MD. (2008). Identification of adult hepatic progenitor cells capable of repopulating injured rat liver. Hepatology 47:636–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yovchev MI, Grozdanov PN, Joseph B, Gupta S. and Dabeva MD. (2007). Novel hepatic progenitor cell surface markers in the adult rat liver. Hepatology 45:139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus AJ, Coyne TM, Rauch J, Woodbury D. and Black IB. (2008). Isolation, characterization, and differentiation of stem cells derived from the rat amniotic membrane. Differentiation 76:130–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parolini O, Alviano F, Bagnara GP, Bilic G, Buhring HJ, Evangelista M, Hennerbichler S, Liu B, Magatti M, et al. (2008). Concise review: isolation and characterization of cells from human term placenta: outcome of the first international Workshop on Placenta Derived Stem Cells. Stem Cells 26:300–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]