Abstract

Importance

NRAS and BRAF mutations in melanoma inform current treatment paradigms but their role in survival from primary melanoma has not been established. Identification of patients at high risk of melanoma-related death based on their primary melanoma characteristics before evidence of recurrence could inform recommendations for patient follow-up and eligibility for adjuvant trials.

Objective

To determine tumor characteristics and survival from primary melanoma by somatic NRAS and BRAF status.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A population-based study with median follow-up of 7.6 years for 912 patients with first primary cutaneous melanoma analyzed for NRAS and BRAF mutations diagnosed in the year 2000 from the United States and Australia in the Genes, Environment and Melanoma Study and followed through 2007.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Tumor characteristics and melanoma-specific survival of primary melanoma by NRAS and BRAF mutational status.

Results

The melanomas were 13% NRAS+, 30% BRAF+, and 57% with neither NRAS nor BRAF mutation (wildtype). In a multivariable model including clinicopathologic characteristics, NRAS+ melanoma was associated (P<.05) with mitoses, lower tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) grade, and anatomic site other than scalp/neck and BRAF+ melanoma was associated with younger age, superficial spreading subtype, and mitoses, relative to wildtype melanoma. There was no significant difference in melanoma-specific survival for melanoma harboring mutations in NRAS (HR 1.7, 95% CI, 0.8–3.4) or BRAF (HR, 1.5, 95% CI, 0.8–2.9) compared to wildtype melanoma adjusted for age, sex, site, AJCC tumor stage, TIL grade, and study center. However, melanoma-specific survival was significantly poorer for higher risk (T2b or higher stage) tumors with NRAS (HR 2.9; 95% CI 1.1–7.7) or BRAF (HR 3.1; 95% CI 1.2–8.5) mutations but not for lower risk (T2a or lower) tumors (P=.65) adjusted for age, sex, site, AJCC tumor stage, TIL grade, and study center.

Conclusions and Relevance

Lower TIL grade for NRAS+ melanoma suggests it has a more immunosuppressed microenvironment, which may impact its response to immunotherapies. Further, the approximately three-fold increased death rate for higher risk tumors harboring NRAS or BRAF mutations compared to wildtype melanomas after adjusting for other prognostic factors indicates that the prognostic implication of NRAS and BRAF mutations deserves further investigation, particularly in higher AJCC stage primary melanomas.

Keywords: oncogene, epidemiology, pathology, RAS, RAF, b-raf, n-ras, neoplasm staging, tumor microenvironment, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

Melanomas frequently harbor mutually exclusive BRAF or NRAS mutations that arise early in tumor progression and persist throughout the course of the disease.1,2 These mutations influence tumor development and maintenance through constitutive activation of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway.1,3 Their clinical relevance is underscored by improved survival of Stage IV patients with BRAF-mutant melanomas treated with BRAF inhibitors alone or in combination with MEK inhibition.4–6 These targeted therapies along with new immunotherapies7,8 are rapidly changing treatment paradigms for metastatic melanoma, and some are under investigation as adjuvant therapies.9 Identification of patients at high risk of death from melanoma based on their primary melanoma tumor characteristics before sign of recurrence remains important to inform evidence-based follow-up of patients and adjuvant trials. Equally important is identification of patients who rarely die from melanoma as they can be spared the risks of adjuvant therapy. However, it remains unknown whether the primary melanoma NRAS/BRAF mutational status influences survival from melanoma during the natural course of the disease.

To date, studies of NRAS and BRAF mutations in primary melanoma have mostly been retrospective and examined all-cause rather than disease-specific survival.10–17 Many selected cases based on referral to a particular center,11–15,17 applied additional criteria such as selection of frozen16 or metastatic14 tissues for analysis, or included only nodular18 or vertical growth phase19 melanoma. Several studies determined BRAF but not NRAS mutations.12,17,20 Only two studies included more than one center and examined NRAS and BRAF mutations in relationship to melanoma-specific survival. Of these, Devitt et al.21 found that NRAS exon 3 and BRAF V600E mutations translated into worse melanoma-specific survival in a prospective cohort of 249 primary melanoma cases from two Australian tertiary melanoma referral centers. Wu et al.22 found BRAF V600E mutation to be associated with an unfavorable melanoma-specific survival for 127 primary melanomas diagnosed in women enrolled in the Nurse’s Health Study.

We examined tumor characteristics and melanoma-specific survival by NRAS and BRAF mutation status in 912 incident first primary cutaneous invasive melanomas from patients diagnosed in 2000 from Australia (New South Wales) or the United States (North Carolina, Michigan, and California) enrolled in the population-based Genes, Environment, and Melanoma (GEM) Study. The primary melanomas were analyzed for NRAS and BRAF mutations. Our median 7.6-year observation period concluded prior to 2011 when the US Food and Drug Administration and Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration began approving new systemic therapies that improve overall survival in metastatic melanoma patients.

METHODS

Study Population

The GEM study included single and multiple primary cutaneous melanoma patients diagnosed between 1998 and 2003 from Australia, Canada, Italy and the United States.23–27 The institutional review board at the coordinating center, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and each participating institution approved the study protocol. Each study participant provided informed written consent. We sought tumor sections from 1,547 participants’ first primary invasive melanoma diagnosed in 2000 from New South Wales (Australia), California, North Carolina, and Michigan.

Histopathology slides were centrally reviewed as previously described.28,29 Mitoses were defined as present or absent.30 TIL grade was scored as absent, nonbrisk, or brisk using a previously defined grading system.31 All data items were available for the T classification describing the state of the primary tumor in the AJCC TNM (tumor, regional nodes, distant metastasis) melanoma staging system; data on regional nodal and distant metastases were not available.

Melanoma treatment information was not available; however, the follow-up period at all study centers ended before recent approvals of new systemic agents that alter the natural course of disease.4–8 Information about deaths from melanoma or other causes was obtained for participants from the National Death Index for the US study centers and the cancer registry for the Australian study center as previously described.28 Patient follow-up for vital status was complete to the end of 2007.

NRAS and BRAF Mutational Analysis

Of eligible GEM participants, 912 (59% of 1,547) had formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded melanomas successfully analyzed for NRAS and BRAF mutations. When indicated because of small tumor size or admixture of nonmalignant cells, tumor cells were selectively procured using laser capture microdissection. Tumor DNA was analyzed for BRAF exon 15 (including codon 600) and NRAS exon 2 and 3 (including codons 61, 12, 13) mutations using single-strand conformational polymorphism (SSCP) analysis and radiolabeled sequencing of SSCP-positive samples as previously described.32,33 All mutations were confirmed by sequencing an independently amplified DNA fragment to eliminate mutational artifacts. The NRAS/BRAF status of 214 (98% of 218) cases from North Carolina previously had been reported.33

Statistical Methods

BRAF and NRAS mutations were mutually exclusive, and melanomas were grouped as: NRAS+ (exon 2 or 3 mutation), BRAF+ (exon 15 mutation), or wildtype (neither NRAS nor BRAF mutation) for analyses. Pearson’s chi-square tests and Wilcoxon tests were used to compare cases analyzed for NRAS and BRAF mutations to those not analyzed.

To identify factors that independently distinguished NRAS+ or BRAF+ from wildtype melanoma, a multivariable model was developed that included all clinicopathologic features and study center. We used polytomous logistic regression for this purpose to estimate simultaneously the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) with NRAS+ and BRAF+ compared to wildtype melanoma adjusted for study center. Statistical significance was assessed using Wald tests. Linear trend was tested when appropriate using the Wald statistic with those variables treated as a single ordinal variable. We also report results from a similar model examining the association of NRAS+ and BRAF+ compared to wildtype melanoma with AJCC tumor stage. . Statistical tests were two-sided with P<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Survival time was accumulated from the diagnosis date until date of death due to melanoma or the end of follow-up (censored patients). Patients were censored at the time of death from any cause other than melanoma. Of the 912 patients who entered the study with first primary melanoma, 40 developed a second primary melanoma during the ascertainment period, and the occurrence of a second primary was included as a time-dependent covariate. The NRAS/BRAF mutational status and pathologic characteristics of their thicker melanoma was utilized in the survival analysis, as previously published.28,29

Survival curves by NRAS and BRAF status were visualized using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using a log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CI by NRAS/BRAF status were estimated in Cox regression models adjusted for age, sex, study center, and the time-dependent covariate and then in fully adjusted models that also included anatomic site, TIL grade, and AJCC tumor stage. Scalp/neck and face/ears were included as separate covariates as scalp/neck, but not face/ear, melanoma predicts worse survival.34–36 TIL grade was included as higher TIL grade of primary melanoma is associated with better melanoma-specific survival.29 To account for the competing risk of death from other causes, we performed Fine and Gray’s proportional subdistribution hazards regression models37 to assess the effects of covariates on the subdistribution hazard for death as a result of melanoma. The likelihood ratio test was used to test each interaction, comparing a model with the main effects to a model with the main effects and the interaction term with an a priori alpha of 0.238

Tests based on Schoenfeld residuals and graphical methods using Kaplan-Meier curves showed no evidence that proportional hazards assumptions were violated for mutational status. SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) version 9.3 was used for all analyses except for Kaplan-Meier curves, which were implemented in STATA/IC 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The participants whose tumors were analyzed for NRAS and BRAF mutations (n=912) were compared to 635 participants whose tumors were unavailable (n=560), insufficient (n=43), or failed molecular analysis (n=32). There were no significant differences (all P>.05) based on median age, sex, site, median Breslow thickness, or melanoma death.

Of the 912 participants with NRAS/BRAF mutational status of their first primary invasive melanomas available, 54% were from Australia and 46% from the United States (Table 1). The participants were 54% male with a median age of 57 years. The median melanoma Breslow thickness was 0.74 mm.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 912 First Primary Invasive Cutaneous Melanoma Analyzed for BRAF and NRAS Mutations

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Australia | 488 (54) |

| United States | 424 (46) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 501 (55) |

| Female | 411 (45) |

| Age at diagnosis, years | |

| Median (IQR) | 57 (25) |

| Breslow thickness, mm | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.74 (0.89) |

| BRAF and NRAS mutation | |

| Wildtype (NRAS−/BRAF−) | 516 (57) |

| NRAS+ | 123 (13) |

| BRAF+ | 273 (30) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range.

NRAS and BRAF Mutational Frequencies and Spectra

The melanomas were 13% NRAS+, 30% BRAF+, and 57% wildtype (with neither NRAS nor BRAF mutation (Table 1 and eTable 1). Of NRAS+ melanomas, 92% harbored mutations in exon 3 and 8% in exon 2; 93% of exon 3 mutations were at codon 61. Of BRAF+ melanomas, 72% carried BRAF V600E, 21% BRAF V600K, and 7% other BRAF exon 15 mutations.

Clinicopathologic Features

We examined age, sex, and pathologic characteristics comparing NRAS+ and BRAF+ to wildtype melanoma for the 892 melanomas with complete data for all variables (Table 2). After adjustment for study center, NRAS+ melanoma was significantly associated (P<.05) with each of the pathologic characteristics, but not sex or age; and BRAF+ melanoma was associated (P<.05) with each of the clinicopathologic characteristics, but not sex, ulceration or TIL grade.

Table 2.

Relationship between Tumor NRAS+ and BRAF+ Mutational Status and Cliniopathologic Features for First Primary Melanomas from 892 Patientsa

| Adjusted for Study Centerb | Fully Adjustedc | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Compared with Wildtype Melanomas | Compared with Wildtype Melanomas | |||||||||

| Wildtype | NRAS+ | BRAF+ | Adjusted NRAS+ | Adjusted BRAF+ | Adjusted NRAS+ | Adjusted BRAF+ | |||||

| Characteristic | (n = 503) | (n = 122) | (n = 267) | OR (95% CI) | Pd | OR (95% CI) | Pd | OR (95% CI) | Pd | OR (95% CI) | Pd |

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 279 (55) | 70 (57) | 144 (54) | Reference | .83 | Reference | .54 | Reference | .59 | Reference | .33 |

| Female | 224 (45) | 52 (43) | 123 (46) | 1.0 (0.6–1.4) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | ||||

| Age at diagnosis, years |

|||||||||||

| <50 | 149 (30) | 25 (21) | 125 (47) | Reference | .07d | Reference | <.001d | Reference | .11d | Reference | .001d |

| 50–69 | 201 (40) | 54 (44) | 100 (37) | 1.6 (1.0–2.7) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | ||||

| >70 | 153 (30) | 43 (35) | 44 (16) | 1.7 (1.0–3.0) | 0.4 (0.2–0.5) | 1.7 (0.9–3.1) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | ||||

| Anatomic site | |||||||||||

| Trunk/pelvis | 198 (39) | 54 (44) | 147 (55) | Reference | .007 | Reference | <.001 | Reference | .011 | Reference | .13 |

| Scalp/neck | 40 (8) | 1 (1) | 11 (4) | 0.1 (0.01–0.7) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 0.1 (0.01–0.6) | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | ||||

| Face/ears/othere | 69 (14) | 10 (8) | 18 (7) | 0.5 (0.3–1.1) | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | ||||

| Upper extremities | 95 (19) | 37 (30) | 43 (16) | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | ||||

| Lower extremities | 101 (20) | 20 (16) | 48 (18) | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | ||||

| Histologic subtype | |||||||||||

| Superficial spreading |

320 (64) | 80 (66) | 227 (85) | Reference | .002 | Reference | <.001 | Reference | .17 | Reference | <.001 |

| Nodular | 38 (8) | 21 (17) | 17 (6) | 2.2 (1.2–4.0) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 1.1 (0.6–2.3) | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | ||||

| Lentigo maligna | 90 (18) | 9 (7) | 15 (6) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | ||||

| Unclassified/otherf | 55 (11) | 12 (10) | 8 (3) | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | ||||

| Breslow thickness, mm |

|||||||||||

| 0.01–1.00 | 349 (69) | 59 (48) | 164 (61) | Reference | <.001 | Reference | .01 | Reference | .87 | Reference | .34 |

| 1.01–2.00 | 86 (17) | 34 (28) | 74 (28) | 2.3 (1.4–3.8) | 1.8 (1.2–2.6) | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | ||||

| 2.01–4.00 | 49 (10) | 19 (16) | 21 (8) | 2.2 (1.2–4.1) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | ||||

| >4.00 | 19 (4) | 10 (8) | 8 (3) | 3.2 (1.4–7.3) | 0.9 (0.4–2.1) | 1.3 (0.4–3.7) | 0.9 (0.3–2.7) | ||||

| Ulceration | |||||||||||

| Absent | 467 (93) | 104 (85) | 248 (93) | Reference | .013 | Reference | .84 | Reference | .85 | Reference | .54 |

| Present | 36 (7) | 18 (15) | 19 (7) | 2.2 (1.2–4.0) | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | 1.3 (0.6–2.6) | ||||

| Mitoses | |||||||||||

| Absent | 319 (63) | 43 (35) | 129 (48) | Reference | <.001 | Reference | <.001 | Reference | .04 | Reference | .02 |

| Present | 184 (37) | 79 (65) | 138 (52) | 3.1 (2.1–4.8) | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | 1.8 (1.0–3.3) | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) | ||||

| Growth phase | |||||||||||

| Radial | 196 (39) | 22 (18) | 68 (25) | Reference | <.001 | Reference | .002 | Reference | .11 | Reference | .12 |

| Vertical | 307 (61) | 100 (82) | 199 (75) | 3.2 (1.9–5.3) | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 1.7 (0.9–3.2) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | ||||

| TIL grade | |||||||||||

| Absent | 96 (19) | 38 (31) | 45 (17) | Reference | <.001d | Reference | .39d | Reference | .002d | Reference | .74d |

| Nonbrisk | 334 (66) | 75 (61) | 186 (70) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 1.3 (0.8–1.9) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | ||||

| Brisk | 73 (15) | 9 (7) | 36 (13) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | ||||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; TIL, tumor infiltrating lymphocyte.

We used polytomous logistic regression to estimate the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals with NRAS+ and BRAF+ melanoma simultaneously compared to wildtype. Melanomas (n = 20) with one or more data points missing for ulceration (n = 19), mitoses (n = 19), growth phase (n = 19), or TIL grade (n = 20) were excluded.

Adjusted for study center.

Included all variables in the table and adjusted for study center.

Where noted for, linear trend was tested using the Wald statistic with the variable treated as a single ordinal variable.

Other includes melanomas on the face/ears and other head/neck melanomas with unspecified sites.

Other includes acral lentiginous, spindle cell, nevoid, and Spitzoid melanomas.

When all clinicopathologic characteristics were included in one model adjusted for study center, NRAS+ tumors were significantly associated (P<.05) with anatomic site other than scalp/neck (OR 0.1, 95% CI, 0.01–0.6 for scalp/neck vs. trunk/pelvis), presence of mitoses (OR 1.8, 95% CI, 1.0–3.3), and lower TIL grade (ORs 0.5, 95% CI, 0.3–0.8 for nonbrisk and 0.3, 95% CI, 0.5–0.7 for brisk, vs. absent TILs). In this model, BRAF+ melanoma was associated with younger age (ORs 0.7, 95% CI, 0.5–1.0 for ages 50–69 and 0.5, 95% CI, 0.3–0.8 for >70, vs. <50 years), superficial spreading subtype (ORs 0.5, 95% CI, 0.2–1.0 for nodular, 0.4, 95% CI, 0.2–0.7 for lentigo maligna, and 0.2, 95% CI, 0.1–0.5 for unclassified/other, vs. superficial spreading), and presence of mitoses (OR 1.7, 95% CI, 1.1–2.6) (Table 2).

The relationships between NRAS+ and BRAF+ tumors with AJCC tumor stage relative to wildtype tumors were examined, adjusted for other prognostic factors (age, sex, anatomic site, and TIL grade) and study center (Table 3). NRAS+ and BRAF+ melanomas were each more frequent among higher tumor stages (P for trend<.001 and P for trend=.04, respectively).

Table 3.

Relationships between Tumor NRAS and BRAF Mutational Status and AJCC Tumor Stage for 892 First Primary Melanomasa

| No. (%) | Compared with Wildtype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wildtype | NRAS+ | BRAF+ | Adjusted NRAS+c | Adjusted BRAF+c | |||

| AJCC Tumor Stageb |

(n = 503) | (n = 122) | (n = 267) | OR | Ptrendd | OR | Ptrendd |

| T1a | 286 (57) | 36 (30) | 121 (46) | Reference | <.001 | Reference | .04 |

| T1b/T2a | 143 (28) | 53 (43) | 111 (41) | 2.7 (1.6–4.3) | 1.8 (1.3–2.6) | ||

| T2b/T3a | 38 (8) | 16 (13) | 19 (7) | 2.9 (1.4–5.8) | 1.4 (0.7–2.5) | ||

| T3b/T4a | 26 (5) | 11 (9) | 11 (4) | 3.1 (1.3–7.1) | 1.3 (0.6–2.7) | ||

| T4b | 10 (2) | 6 (5) | 5 (2) | 3.8 (1.2–12.0) | 1.9 (0.6–5.9) | ||

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; OR, odds ratio; TIL, tumor infiltrating lymphocyte.

We used polytomous logistic regression to estimate the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals with NRAS+ and BRAF+ melanoma simultaneously compared to wildtype. Melanomas (n = 20) with one or more data points missing for ulceration (n = 19), mitoses (n = 19), or TIL grade (n = 20) were excluded.

T1a, Breslow thickness ≤1.0 mm and no ulceration and absent mitoses; T1b, Breslow thickness ≤1.0 mm and presence of ulceration or present mitoses; T2a, Breslow thickness 1.01–2.0 mm without ulceration; T2b, Breslow thickness 1.01–2.0 mm with ulceration; T3a, Breslow thickness 2.01–4.0 mm without ulceration; T3b, Breslow thickness 2.01–4.0 mm with ulceration, T4a, Breslow thickness >4.0 mm without ulceration; T4b, Breslow thickness >4.0 mm with ulceration.

Adjusted for age (<50, 50–69, >70), sex, anatomic site (scalp/neck, face/ears/other, trunk/pelvis, upper extremities, lower extremities), TIL grade, study center.

Linear trend was tested using the Wald statistic when AJCC tumor stage was treated as a single ordinal variable.

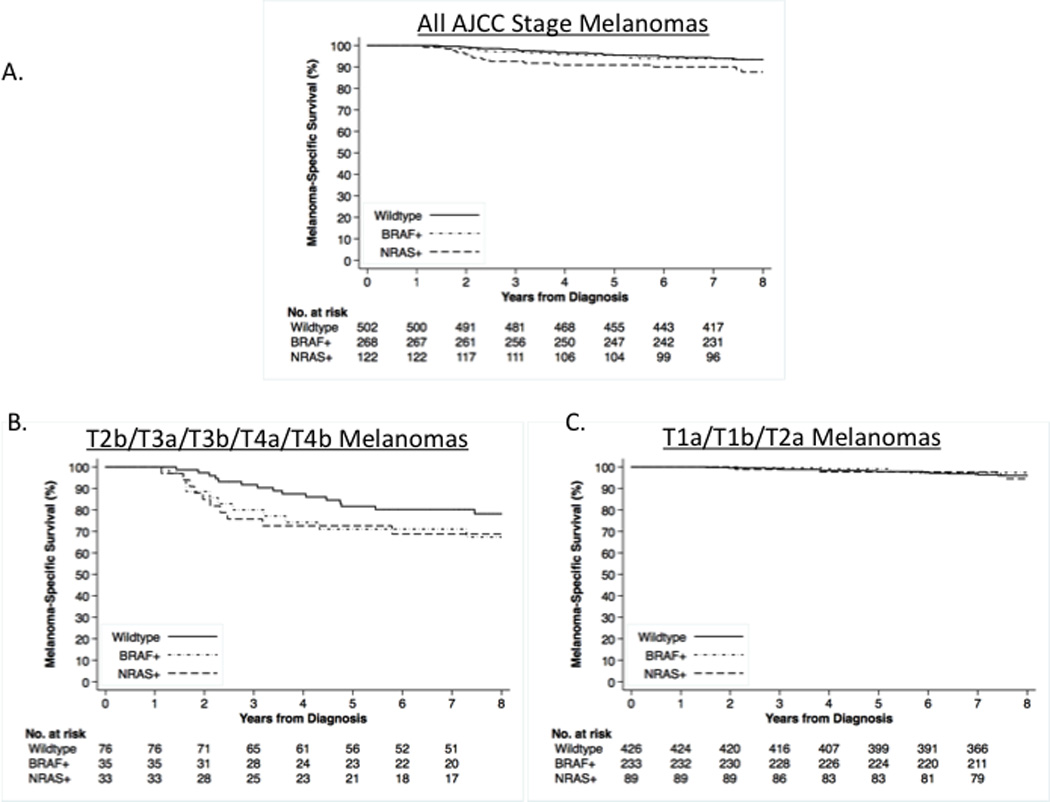

Melanoma-Specific Survival

There were 62 melanoma deaths in 892 patients with complete AJCC tumor stage and TIL grade information during a median follow-up time of 7.6 years. Five-year survival was 91% (95% CI, 86–96%) with NRAS+; 95% (95% CI, 93–98%) with BRAF+; and 95% (95% CI, 94–97%) with wildtype melanoma (log-rank test P=.088) (Figure 1a).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier melanoma-specific survival probabilities by primary melanoma NRAS and BRAF mutational status are shown for participants with melanomas (n=892). Patients with single primary melanoma were diagnosed in 2000. Patient follow-up for vital status was complete to the end of 2007. A. Melanoma-specific survival for all primary melanomas; B. Melanoma-specific survival for higher risk (T2b or higher AJCC stage) primary melanomas); C. Melanoma-specific survival for lower risk (T2a or lower AJCC stage) primary melanomas.

In a Cox model adjusted for age, sex, and study center, NRAS+ (HR 1.8, 95% CI, 0.9–3.4) and BRAF+ (HR 1.3, 95% CI, 0.7–2.4) relative to wildtype melanoma were not significantly associated with melanoma-specific survival (P=.19). Further adjusting for anatomic site, tumor stage, and TIL grade, the HR for NRAS+ melanoma was 1.7 while the HR of BRAF+ melanoma increased to 1.5; the results remained non-significant (P=.27) (Table 4). In the fully adjusted model, younger age, upper extremities relative to trunk, and lower tumor stage were significantly (P<.05) associated with improved melanoma-specific survival, while scalp/neck site was associated with worse melanoma-specific survival (HR 2.1; 95% CI, 0.9 to 5.1) (eTable 2). We found a significant interaction of NRAS/BRAF mutational status with tumor stage (P for interaction=.04) but not with age, sex, site, TIL grade, or study center in the full model.

Table 4.

Hazard Ratios for Melanoma-Specific Death According to Tumor BRAF and NRAS Mutational Status Among 892 Patients with Primary Melanoma

| Cox Proportional Hazards Model | Proportional Subdistribution

Hazards Model for Competing-Risks |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Censored | Melanoma Death |

Death from Other Cause |

Partially Adjustedb | Fully Adjustedc | Partially Adjustedb | Fully Adjustedc | |||||

| Characteristic | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | sHR (95% CI) |

P | sHR (95% CI) | P |

| All primary melanomasa | |||||||||||

| All stage melanomas | (n=750) | (n = 62) | (n=80) | ||||||||

| NRAS/BRAF Status | |||||||||||

| Wildtype (NRAS−/BRAF−) | 420 (84) | 31 (6) | 51 (10) | Reference | .19 | Reference | .27 | Reference | .18 | Reference | .28 |

| NRAS+ | 94 (77) | 14 (11) | 14 (11) | 1.8 (0.9–3.4) | 1.7 (0.8–3.4) | 1.8 (1–3.5) | 1.7 (0.8–3.6) | ||||

| BRAF+ | 236 (88) | 17 (6) | 15 (6) | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) | 1.5 (0.8–2.9) | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) | 1.6 (0.8–3.2) | ||||

| Stratified by AJCC Stage | |||||||||||

| Stage T1a/T1b/T2a | (n=667) | (n = 26) | (n=55) | ||||||||

| NRAS/BRAF Status | |||||||||||

| Wildtype (NRAS−/BRAF−) | 374 (88) | 16 (4) | 36 (8) | Reference | .84 | Reference | .65 | Reference | .83 | Reference | .67 |

| NRAS+ | 77 (87) | 4 (4) | 8 (9) | 1.1 (0.4–3.4) | 0.9 (0.3–3.0) | 1.2 (0.4–3.5) | 0.9 (0.3–2.9) | ||||

| BRAF+ | 216 (93) | 6 (3) | 11 (5) | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) | 0.8 (0.3–2) | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) | ||||

|

Stage T2b/T3a/T3b/T4a/T4b |

(n=83) | (n = 36) | (n=25) | ||||||||

| NRAS/BRAF Status | |||||||||||

| Wildtype (NRAS−/BRAF−) | 46 (61) | 15 (20) | 15 (20) | Reference | .13 | Reference | .04 | Reference | .09 | Reference | .02 |

| NRAS+ | 17 (52) | 10 (30) | 6 (18) | 1.7 (0.8–3.9) | 2.9 (1.1–7.7) | 1.8 (0.8–4.2) | 3 (1.1–8.2) | ||||

| BRAF+ | 20 (57) | 11 (31) | 4 (11) | 2.3 (1.0–5.1) | 3.1 (1.2–8.5) | 2.4 (1.1–5.3) | 3.6 (1.3–9.5) | ||||

| Primary melanomas limited to NRAS codon 61 and BRAF V600E mutant and wildtype melanomas | |||||||||||

| All stage melanomas | (n=685) | (n = 57) | (n=67) | ||||||||

| NRAS/BRAF Status | |||||||||||

| Wildtype (NRAS−/BRAF−) | 420 (84) | 31 (6) | 51 (10) | Reference | .12 | Reference | .17 | Reference | .11 | Reference | .19 |

| NRAS codon 61+ | 90 (79) | 13 (11) | 11 (10) | 1.9 (1.0–3.6) | 1.9 (0.9–4.0) | 1.9 (1–3.7) | 1.9 (0.9–4.2) | ||||

| BRAF V600E+ | 175 (91) | 13 (7) | 5 (3) | 1.6 (0.8–3.0) | 1.7 (0.8–3.5) | 1.6 (0.8–3.2) | 1.8 (0.8–4) | ||||

| Stratified by AJCC Stage | |||||||||||

| Stage T1a/T1b/T2a | (n=607) | (n = 25) | (n=45) | ||||||||

| NRAS/BRAF Status | |||||||||||

| Wildtype (NRAS−/BRAF−) | 374 (88) | 16 (4) | 36 (8) | Reference | .92 | Reference | .87 | Reference | .91 | Reference | .89 |

| NRAS codon 61+ | 74 (88) | 4 (5) | 6 (7) | 1.3 (0.4–3.8) | 1.1 (0.3–3.6) | 1.3 (0.4–3.7) | 1.1 (0.4–3.4) | ||||

| BRAF V600E+ | 159 (95) | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 1.0 (0.4–2.8) | 0.8 (0.3–2.3) | 1 (0.4–2.8) | 0.8 (0.2–2.5) | ||||

|

Stage T2b/T3a/T3b/T4a/T4b |

(n=78) | (n = 32) | (n=22) | ||||||||

| NRAS/BRAF Status | |||||||||||

| Wildtype (NRAS−/BRAF−) | 46 (61) | 15 (20) | 15 (20) | Reference | .13 | Reference | .04 | Reference | .10 | Reference | .03 |

| NRAS codon 61+ | 16 (53) | 9 (30) | 5 (17) | 1.7 (0.7–3.9) | 3.2 (1.1–9.7) | 1.8 (0.7–4.2) | 3.3 (1.1–10.1) | ||||

| BRAF V600E+ | 16 (62) | 8 (31) | 2 (8) | 2.4 (1.0–6.0) | 3.8 (1.2–11.8) | 2.6 (1–6.6) | 4.3 (1.3–14.8) | ||||

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; HR, hazard ratio; sHR, subdistribution hazard ratio; TIL, tumor infiltrating lymphocyte.

Of the 912 patients who entered the study with first primary melanoma, 40 developed a second melanoma during the ascertainment period and were treated as time-dependent and the BRAF/NRAS mutational status and pathologic characteristics of their thicker melanoma was utilized in the survival analysis. Excluded from this analysis wee 20 participants with missing AJCC tumor stage or TIL grade for their melanoma. In the cox models death from other causes were considered as censored.

The Cox models /proportional subdistribution hazards models were adjusted for age (continuous), sex, and study center.

The Cox models/proportional subdistribution hazards models were adjusted for age (continuous), sex, anatomic site (trunk/pelvis, scalp/neck, face/ears/other, upper extremities, lower extremities), AJCC tumor stage (T1a, T1b/T2a, T2b/T3a, T3b/T4a, T4b), TIL grade, and study center.

Given the significant interaction with stage, we categorized tumors as in higher (T2b/T3a/T3b/T4a/T4b) and lower (T1a/T1b/T2a) risk AJCC stages39 (Table 4). In our study, 25% (36/144) of patients with higher risk tumors died of melanoma compared to 3.5% (26/748) with lower risk tumors. For higher risk tumors, 5-year survival was 73% for NRAS+; 71% for BRAF+; and 82% for wildtype melanoma (log-rank test P=.28) (Figure 1b). For lower risk tumors, 5-year survival was 98% for NRAS+; 99% for BRAF+; and 98% for wildtype melanoma (log-rank test P=.61) (Figure 1c).

For higher risk tumors adjusted for age, sex, and study center, the HRs were 1.7 (95% CI, 0.8–3.9) for NRAS+ and 2.3 (95% CI, 1.0–5.1) for BRAF+ compared to wildtype melanoma (P=.13) (Table 4). Further adjusting for anatomic site, tumor stage, and TIL grade, the HRs for NRAS+ and BRAF+ melanoma strengthened to 2.9 (95% CI, 1.1–7.7) and 3.1 (95% CI, 1.2–8.5), respectively, compared to wildtype melanoma (P=.04). Addition of anatomic site in the model explained the strengthening of the estimates for NRAS and BRAF mutations in the full model. For lower risk tumors, NRAS/BRAF mutational subtype was not positively associated with hazard of death in either the partially or fully adjusted models. Similar patterns of higher ORs for higher compared to lower risk tumors were seen in reanalyses stratified by continent despite.

In a reanalysis including only NRAS codon 61 and BRAF V600E and wildtype melanomas, melanoma-specific survival differences based on mutational status remained limited to higher risk tumors (Table 4).

The associations remained similar in competing risk models (Tables 4 and eTable 2)

DISCUSSION

We present data from the largest population-based study to date analyzing tumor characteristics and melanoma specific survival by NRAS and BRAF mutational subtypes. NRAS+ melanoma was associated with anatomic site other than the scalp/neck, presence of mitoses, and lower TIL grade and BRAF+ melanoma with younger age, superficial spreading subtype, and presence of mitoses independently of other clinicopathologic characteristics. We found no significant difference for the risk of melanoma-related death from NRAS+ or BRAF+ compared to wildtype melanoma adjusted for other prognostic factors. However, there was an approximately three-fold increase in melanoma-related death for higher risk (T2b or higher stage) NRAS+ and BRAF+ tumors compared to wildtype, but not for lower risk (T2a or lower stage) tumors adjusting for other prognostic factors.

The NRAS and BRAF mutational frequencies, 13% and 30%, respectively, in our study are within previously reported ranges for primary melanoma.13,21,40 Other studies similarly reported associations of NRAS+ melanoma with older age, trunk and extremity locations, nodular subtype, increased Breslow thickness, and mitoses.13,14,21,40,41 We also confirm BRAF+ melanoma associations with younger age, trunk location, superficial spreading melanoma, mitoses, and vertical growth phase.11,13,14,21,40–44 Ellerhorst et al. in a hospital-based study similarly found that NRAS+ and BRAF+ melanomas tended to present at more advanced AJCC tumor stage,13 while Devitt et al.21 found that NRAS+ tended to be higher stage.

No prior study has reported an association of mitoses with NRAS+ and BRAF+ compared to wildtype melanoma independently of Breslow thickness and other clinicopathologic characteristics. This association may reflect NRAS and BRAF oncogenic activation of the mitogenic RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway.1 Mitoses are considered as a marker for tumor growth.45 Melanoma growth rate, based on self-report, correlates positively with mitotic rate,46 and, thus, NRAS+ and BRAF+ melanomas’ associations with mitoses suggests that they may grow faster than wildtype melanomas. It is in agreement with a significant association between either BRAF or NRAS mutation and fast growing melanomas, calculated by using self-reported time on the skin and Breslow thickness.47

Similar to our results, NRAS+ melanoma has been identified frequently arising on the trunk40 or on the upper13,14 or lower extremities.22 We further refine this knowledge with our report of an inverse association of NRAS+ melanoma for scalp or neck location; the majority of scalp/neck melanomas in GEM were wildtype. This finding and the 2-fold worse survival in GEM for scalp/neck melanoma adjusted for mutational subtype indicate that the poor prognosis of scalp/neck melanoma34–36 is unlikely to be related to NRAS/BRAF mutational status.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to report lower TIL grade for NRAS+ compared to wildtype melanoma. Notably, TIL grade remained associated with NRAS+ melanoma independently of other factors (age, anatomic site, histologic subtype, and Breslow thickness) that we previously found to be associated with TIL grade in GEM.29 Our observation is plausible as oncogenic RAS pathway activation can disrupt antitumor immunity by decreasing expression of antigen-presenting major histocompatibility complexes on the surface of tumor cells and recruiting immunosuppressive regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells to the tumor site.48 Unlike Edlundh-Rose et al.,14 we did not find BRAF+ relative to wildtype melanoma to be associated with higher lymphocyte infiltration; however, their study design and lymphocyte scoring differed from GEM.

We compare our results to other multi-site studies examining melanoma-specific survival by NRAS/BRAF primary melanoma status. Although not reaching statistical significance, our findings of poorer melanoma-specific survival for NRAS+ and BRAF+ (adjusted HRs of 1.7 and 1.5, respectively) compared to wildtype melanoma are in the same direction found by Devitt et al. for NRAS+ and BRAF+ (adjusted HRs of 2.96 and 1.7, respectively) melanoma despite different study designs and adjustments.21 Wu et al. similarly found that NRAS+ and BRAF+ had shorter melanoma-specific survival than wildtype melanoma, with BRAF+ compared to wildtype reaching statistical significance. Thus, these studies and our results combined indicate a modestly worse prognosis for NRAS+ and BRAF+ tumors overall for melanoma-specific survival.

Our study suggests that melanoma-specific survival differences based on NRAS and BRAF mutational status are limited to higher risk tumors. Few deaths occurred in lower risk tumors, and we found no effect of mutational status on survival among lower risk tumors. Thus, our results provide evidence that NRAS/BRAF mutational status may add prognostic information for higher risk tumors. A possible explanation for the increased proportion of deaths for NRAS+ and BRAF+ melanoma limited to higher risk tumors is that higher risk tumors may have acquired another contributing genetic alteration during their progression. Our finding, however, requires confirmation. We are not aware of another study that has analyzed survival by NRAS and BRAF status stratified by tumor stage.

Advantages of our study are its large size, use of current AJCC tumor staging, centralized pathology review by expert dermatopathologists, and comparatively long observational period ending before recent approvals of new systemic agents that alter the natural course of disease.4–8 Any future study examining NRAS and BRAF mutations in primary melanomas in relationship to survival will be confounded by these new treatments.

Our tumor collection and mutational analysis rate of all eligible primary melanomas is similar to or higher than comparable melanoma studies.21,22,49–51 Further, our results are representative of the entire population of melanoma participants enrolled into GEM, as we found no significant differences comparing clinicopathologic characteristics of cases with and without mutation analysis. Population-based prevalence estimates of mutations provided may be useful for budgetary and economic evaluations in present and future pharmacoeconomics studies. Some mutations may have been misclassified, but we minimized this possibility by using laser capture microdissection for all small samples and independently confirming mutations on a separately amplified DNA fragment.

A limitation is that we did not obtain sentinel lymph node (SLN) status so we could not determine whether NRAS/BRAF status provides information beyond SLN status for outcome prediction. We also did not obtain information regarding therapies potentially utilized, such as regional radiation, systemic interferon, or clinical trial participation, which could confound our results. Information on relapse was also not available.

In conclusion, our finding that NRAS+ and BRAF+ melanomas are associated with higher tumor stage at diagnosis indicates that NRAS+ and BRAF+ are less likely than wildtype melanoma to be diagnosed when lower risk and surgically curable. NRAS+ melanoma’s association with lower TIL grade may influence its response to immunotherapies. In GEM, the approximately three-fold increased risk of death from NRAS+ and BRAF+ compared to wildtype melanoma limited to higher risk tumors after adjusting for other prognostic factors indicates that mutational status may be prognostic for this group. This finding could be useful in the identification of patients at high risk of death from melanoma based on their primary melanoma tumor characteristics to inform evidence-based follow-up of patients and determination of eligibility for novel systemic therapy adjuvant trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants R01CA112243, R01CA112524, R01CA112243-05S1, R01CA112524-05S2, U01CA83180, CA098438, R33CA10704339, P30CA016086, P30CA014089, and P30CA008748; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P30ES010126); University of Sydney Medical Foundation Program grant (Bruce Armstrong).

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the preparation of the manuscript; or in the review or approval of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- GEM

Genes, Environment, and Melanoma Study

- HR

hazard ratio

- IQR

interquartile range

- OR

odds ratio

GEM Study Group

Coordinating Center, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY: Marianne Berwick, M.P.H., Ph.D. (Principal Investigator (PI), currently at the University of New Mexico), Colin B. Begg, Ph.D. (co-PI), Irene Orlow, Ph.D. (co-Investigator), Klaus J. Busam, M.D. (Dermatopathologist), Anne S. Reiner, M.P.H. (Biostatistician), Pampa Roy, Ph.D. (Laboratory Technician), Ajay Sharma, M.S. (Laboratory Technician), Emily La Pilla (Laboratory Technician). University of New Mexico, Albuquerque: Marianne Berwick, M.P.H., Ph.D. (PI), Li Luo, Ph.D. (Biostatistician), Kirsten White, MSc (Laboratory Manager), Susan Paine, M.P.H. (Data Manager). Study centers included the following: The University of Sydney and The Cancer Council New South Wales, Sydney, Australia: Bruce K. Armstrong M.B.B.S.; D.Phil., (PI), Anne Kricker, Ph.D. (co-PI), Anne E. Cust, Ph.D. (co-Investigator); Menzies Research Institute Tasmania, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia: Alison Venn, Ph.D. (current PI), Terence Dwyer, M.D. (PI, currently at University of Oxford, United Kingdom), Paul Tucker, M.D. (Dermatopathologist); British Columbia Cancer Research Centre, Vancouver, Canada: Richard P. Gallagher, M.A. (PI), Donna Kan (Coordinator); Cancer Care Ontario, Toronto, Canada: Loraine D. Marrett, Ph.D. (PI), Elizabeth Theis, M.Sc. (co-Investigator), Lynn From, M.D. (Dermatopathologist); CPO, Center for Cancer Prevention, Torino, Italy: Roberto Zanetti, M.D (PI), Stefano Rosso, M.D., M.Sc. (co-PI); University of California, Irvine, CA: Hoda Anton-Culver, Ph.D. (PI), Argyrios Ziogas, Ph.D. (Statistician); University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: Stephen B. Gruber, M.D., M.P.H., Ph.D. (PI, currently at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA), Timothy Johnson, M.D. (Director of Melanoma Program), Duveen Sturgeon, M.S.N. (co-Investigator, joint at USC-University of Michigan); University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC: Nancy E. Thomas, M.D., Ph.D. (PI), Robert C. Millikan, Ph.D. (previous PI, deceased), David W. Ollila, M.D. (co-Investigator), Kathleen Conway, Ph.D. (co-Investigator), Pamela A. Groben, M.D. (Dermatopathologist), Sharon N. Edmiston, B.A. (Research Analyst), Honglin Hao (Laboratory Specialist), Eloise Parrish, MSPH (Laboratory Specialist), Jill S. Frank, M.S. (Research Assistant), David C. Gibbs, B.S. (Research Assistant), Jennifer I. Bramson (Research Assistant); University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA: Timothy R. Rebbeck, Ph.D. (PI), Peter A. Kanetsky, M.P.H., Ph.D. (co-Investigator, currently at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, Florida); UV data consultants: Julia Lee Taylor, Ph.D. and Sasha Madronich, Ph.D., National Centre for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO.

Footnotes

Author Attributions and Financial Disclosures

Author Contributions: Dr. Nancy E. Thomas had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Thomas, Armstrong, Anton-Culver, Begg, Berwick, Gruber, Kricker.

Acquisition of data: Thomas, Alexander, Armstrong, Anton-Culver, Berwick, Busam, Conway, Edmiston, Frank, From, Groben, Gruber, Hao, Kricker, Ollila, Paine, Parrish

Analysis and interpretation of data: Thomas, Armstrong, Anton-Culver, Berwick, Bramson, Busam, Conway, Cust, Dwyer, Edmiston, Frank, From, Gallagher, Groben, Gruber, Kanetsky, Kricker, Luo, Marrett, Ollila, Orlow, Rosso, Zanetti

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Obtained funding: Thomas, Armstrong, Anton-Culver, Berwick, Conway, Gruber

Administrative, technical, and material support: Thomas, Armstrong, Anton-Culver, Begg, Berwick, Gruber, Kricker.

Study supervision: Thomas, Armstrong, Anton-Culver, Begg, Berwick, Gruber, Kricker.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417(6892):949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omholt K, Platz A, Kanter L, Ringborg U, Hansson J. NRAS and BRAF mutations arise early during melanoma pathogenesis and are preserved throughout tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(17):6483–6488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wellbrock C, Ogilvie L, Hedley D, et al. V599EB-RAF is an oncogene in melanocytes. Cancer Res. 2004;64(7):2338–2342. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60868-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):107–114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):134–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davar D, Tarhini AA, Kirkwood JM. Adjuvant therapy for melanoma. Cancer J. 2012;18(2):192–202. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31824f118b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broekaert SM, Roy R, Okamoto I, et al. Genetic and morphologic features for melanoma classification. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23(6):763–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagore E, Requena C, Traves V, et al. Prognostic value of BRAF mutations in localized cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):858–862. e851–e852. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meckbach D, Bauer J, Pflugfelder A, et al. Survival according to BRAF-V600 tumor mutations--an analysis of 437 patients with primary melanoma. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellerhorst JA, Greene VR, Ekmekcioglu S, et al. Clinical correlates of NRAS and BRAF mutations in primary human melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(2):229–235. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edlundh-Rose E, Egyhazi S, Omholt K, et al. NRAS and BRAF mutations in melanoma tumours in relation to clinical characteristics: a study based on mutation screening by pyrosequencing. Melanoma Res. 2006;16(6):471–478. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000232300.22032.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houben R, Becker JC, Kappel A, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Carcinog. 2004;3(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kannengiesser C, Spatz A, Michiels S, et al. Gene expression signature associated with BRAF mutations in human primary cutaneous melanomas. Molecular oncology. 2008;1(4):425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shinozaki M, Fujimoto A, Morton DL, Hoon DS. Incidence of BRAF oncogene mutation and clinical relevance for primary cutaneous melanomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(5):1753–1757. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akslen LA, Angelini S, Straume O, et al. BRAF and NRAS mutations are frequent in nodular melanoma but are not associated with tumor cell proliferation or patient survival. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(2):312–317. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griewank KG, Murali R, Puig-Butille JA, et al. TERT promoter mutation status as an independent prognostic factor in cutaneous melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(9) doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maldonado JL, Fridlyand J, Patel H, et al. Determinants of BRAF mutations in primary melanomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(24):1878–1890. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devitt B, Liu W, Salemi R, et al. Clinical outcome and pathological features associated with NRAS mutation in cutaneous melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu S, Kuo H, Li WQ, Canales AL, Han J, Qureshi AA. Association between BRAFV600E and NRASQ61R mutations and clinicopathologic characteristics, risk factors and clinical outcome of primary invasive cutaneous melanoma. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25(10):1379–1386. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0443-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Begg CB, Hummer AJ, Mujumdar U, et al. A design for cancer case-control studies using only incident cases: experience with the GEM study of melanoma. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(3):756–764. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Begg CB, Hummer A, Mujumdar U, et al. Familial aggregation of melanoma risks in a large population-based sample of melanoma cases. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15(9):957–965. doi: 10.1007/s10522-004-2474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Millikan RC, Hummer A, Begg C, et al. Polymorphisms in nucleotide excision repair genes and risk of multiple primary melanoma: the Genes Environment and Melanoma Study. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(3):610–618. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orlow I, Begg CB, Cotignola J, et al. CDKN2A germline mutations in individuals with cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(5):1234–1243. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murali R, Goumas C, Kricker A, et al. Clinicopathologic features of incident and subsequent tumors in patients with multiple primary cutaneous melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(3):1024–1033. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2058-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas NE, Kricker A, Waxweiler WT, et al. Comparison of Clinicopathologic Features and Survival of Histopathologically Amelanotic and Pigmented Melanomas: A Population-Based Study. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(12):1306–1314. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas NE, Busam KJ, From L, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte grade in primary melanomas is independently associated with melanoma-specific survival in the population-based genes, environment and melanoma study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(33):4252–4259. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piris A, Mihm MC, Jr, Duncan LM. AJCC melanoma staging update: impact on dermatopathology practice and patient management. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38(5):394–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elder DE, Gimotty PA, Guerry D. Cutaneous melanoma: estimating survival and recurrence risk based on histopathologic features. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(5):369–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2005.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas NE, Alexander A, Edmiston SN, et al. Tandem BRAF mutations in primary invasive melanomas. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122(5):1245–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas NE, Edmiston SN, Alexander A, et al. Number of nevi and early-life ambient UV exposure are associated with BRAF-mutant melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(5):991–997. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lachiewicz AM, Berwick M, Wiggins CL, Thomas NE. Survival differences between patients with scalp or neck melanoma and those with melanoma of other sites in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(4):515–521. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tseng WH, Martinez SR. Tumor location predicts survival in cutaneous head and neck melanoma. J Surg Res. 2011;167(2):192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green AC, Baade P, Coory M, Aitken JF, Smithers M. Population-based 20-year survival among people diagnosed with thin melanomas in Queensland, Australia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13):1462–1467. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selvin S. A Note on the Power to Detect Interaction Effects. In: Kesley J, Marmot M, Stolley P, Vessey M, editors. Statistical Analysis of Epidemiologic Data. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 213–214. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6199–6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hacker E, Hayward NK, Dumenil T, James MR, Whiteman DC. The Association between MC1R Genotype and BRAF Mutation Status in Cutaneous Melanoma: Findings from an Australian Population. J Invest Dermatol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goel VK, Lazar AJ, Warneke CL, Redston MS, Haluska FG. Examination of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and PTEN in primary cutaneous melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(1):154–160. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viros A, Fridlyand J, Bauer J, et al. Improving melanoma classification by integrating genetic and morphologic features. PLoS Med. 2008;5(6):e120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu W, Kelly JW, Trivett M, et al. Distinct clinical and pathological features are associated with the BRAF(T1799A(V600E)) mutation in primary melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(4):900–905. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Estrozi B, Machado J, Rodriguez R, Bacchi CE. Clinicopathologic findings and BRAF mutation in cutaneous melanoma in young adults. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2014;22(1):57–64. doi: 10.1097/pdm.0b013e318298c1d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chung KT, Nilson EH, Case MJ, Marr AG, Hungate RE. Estimation of growth rate from the mitotic index. Applied microbiology. 1973;25(5):778–780. doi: 10.1128/am.25.5.778-780.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu W, Dowling JP, Murray WK, et al. Rate of growth in melanomas: characteristics and associations of rapidly growing melanomas. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(12):1551–1558. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.12.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagore E, Hacker E, Martorell-Calatayud A, et al. Prevalence of BRAF and NRAS mutations in fast-growing melanomas. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2013;26(3):429–431. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mandala M, Merelli B, Massi D. Nras in melanoma: Targeting the undruggable target. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fargnoli MC, Pike K, Pfeiffer RM, et al. MC1R variants increase risk of melanomas harboring BRAF mutations. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(10):2485–2490. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee EY, Williamson R, Watt P, Hughes MC, Green AC, Whiteman DC. Sun exposure and host phenotype as predictors of cutaneous melanoma associated with neval remnants or dermal elastosis. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(3):636–642. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richmond-Sinclair NM, Lee E, Cummings MC, et al. Histologic and epidemiologic correlates of P-MAPK, Brn-2, pRb, p53, and p16 immunostaining in cutaneous melanomas. Melanoma Res. 2008;18(5):336–345. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32830d8329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.