Abstract

As the core nationally representative health expenditure survey in the United States, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) is increasingly being used by statistical agencies to track expenditures by disease. However, while MEPS provides a wealth of data, its small sample size precludes examination of spending on all but the most prevalent health conditions. To overcome this issue, statistical agencies have turned to other public data sources, such as Medicare and Medicaid claims data, when available. No comparable publicly available data exist for those with employer-sponsored insurance. While large proprietary claims databases may be an option, the relative accuracy of their spending estimates is not known. This study compared MEPS and MarketScan estimates of annual per person health care spending on individuals with employer-sponsored insurance coverage. Both total spending and the distribution of annual per person spending differed across the two data sources, with MEPS estimates 10 percent lower on average than estimates from MarketScan. These differences appeared to be a function of both underrepresentation of high expenditure cases and underestimation across the remaining distribution of spending.

I. Introduction

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) estimates that health care expenditures reached a share of 16 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2006; the BEA is responding to this trend by working to develop an understanding of what the increased expenditure share represents. Existing health measures in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs) and the National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA) provide estimates on medical care that individuals purchase (i.e. doctor's office visit or purchase of a drug) and how these purchases are financed (i.e. private insurance, government assistance, or out of pocket) (Sensenig and Wilcox (2001); Heffler et al. 2009). While these estimates are useful for some purposes, they do not provide information on the particular disease being treated with each purchase. Estimates of spending by disease are required for measuring the returns to treatment, whether or not the expenditure is beneficial, because that benefit depends on the particular disease one has. For statistical agencies, spending by disease is required to properly measure real output, inflation and productivity for this important sector.

In this light, efforts are now focused on measuring health expenditures, and creating subsequent health care price indexes, by disease (Rosen and Cutler 2007; Rosen and Cutler 2009). To take on such a task requires data on the health conditions driving spending. Initial efforts have turned to the national expenditure surveys for these data – most notably, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, or MEPS (Bradley et. al 2009).

While MEPS provides a wealth of data, its small sample size precludes examination of spending on all but the most prevalent health conditions (Machlin et al. 2009; Mackie 2009). To overcome this issue, statistical agencies have turned to other public data sources when available. For example, the Bureau of Economic Analysis is considering commercial claims data as a potential data source to measure medical care spending in the national accounts (Aizcorbe, Retus and Smith 2007).

Despite the availability of quality data for patients covered by public programs, such as Medicare, there remains a lack of publicly available health care data on the largest segment of U.S. healthcare users: commercially insured patients and their families, who account for an estimated 68% of the total population.1 For the commercially-insured population, multiple large proprietary databases exist; however, it is not clear how representative these data truly are. Before we can confidently rely on these datasets for their sufficient sample size for disease-based pricing, we need to understand more generally how the heath care expenditures in these commercial databases compare with expenditures in MEPS. While some differences are to be expected, if we understand these differences, we may be able to adjust for them.

This paper compares the 2005 MEPS expenditure estimates of people with coverage through employers to the 2005 Thomson Healthcare MarketScan claims. Our objectives are to better understand how the MarketScan database compares to MEPS and to identify areas requiring further investigation.

II. Study data

The data needed for our disease-based spending estimates must have both expenditures and information on patients' illnesses. While data are typically collected from providers at the encounter level, we need data at the patient level, including information on all the care received from the different types of providers. For commercially-insured patients, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey is the only government source for this type of information. While the MEPS data are nationally representative, the small sample size precludes examination of health expenditures for all but the most prevalent health conditions (Machlin et al. 2009; Mackie 2009).

Commercial claims data, on the other hand, provide much larger sample sizes but at the cost of representativeness (Mackie 2009; Rosen and Cutler 2009). The claims data may be adjusted with sampling weights to provide nationally-representative estimates.

A. Medical expenditure panel survey (MEPS)

The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, which is conducted by the Department of Health and Human Services' Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is a nationally representative survey of the health care utilization and expenditures of the civilian non-institutionalized U.S. population. The survey sample is drawn from the prior year's National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) sampling frame. The survey uses an overlapping panel design in which the data are collected through a series of five rounds of interviews; the data from the overlapping panels are then used to produce annual estimates. For each household surveyed, MEPS interviews a single respondent – the family member most knowledgeable about the entire household's health and healthcare use (Zuvekas and Olin 2009a). The sample includes approximately 15,000 families and 35,000 individuals each year (Cohen, Cohen and Banthin 2009).

MEPS provides both household and patient-level data on personal health care expenditures. The survey contains data on health services used as well as the frequency with which households use them, their cost, and how they are paid for. MEPS actually consists of a family of 3 interrelated surveys: the Household Component (HC), the Medical Provider Component (MPC), and the Insurance Component (IC). The Household Component of the survey interviews individuals and families; the Medical Provider Component supplements this information by verifying prices, but not quantities, from medical providers and pharmacies. The final component is the Insurance Component, which collects data from employers regarding the employers’ characteristics and the insurance they offer their employees (Sing et. al.2006; Zuvekas and Olin 2009b; and Cohen, Cohen and Banthin 2009).

As a data source, MEPS has some key advantages over insurance claims data. It is a well-known, nationally representative sample, and is generally regarded as a high-quality source of data on high-prevalence health conditions. Another important strength of the MEPS data is its ability to directly link expenditures from all services (across all types of providers) to patient care events (Mackie 2009; Sing et. al. 2006). Finally, MEPS is the only data set available to capture the expenditures of the uninsured (Cohen 2009).

B. Marketscan

The Thomson Healthcare MarketScan Research Databases are a nationwide convenience sample of patients from all providers of care. MarketScan collects data from employers, health plans, and state-level Medicaid agencies and all claims have been paid and adjudicated. Each enrollee has a unique identifier and can be identified at the three-digit zip code level2. This paper uses the Commercial Claims and Encounters Database portion of the MarketScan Databases, which includes health care utilization and cost records at the encounter level, with patient identifiers that may be used to sum expenditures to the patient level.

The Commercial Claims and Encounters Database contains data from employer and health plan sources concerning medical and drug data for several million employer-sponsored insurance (ESI)-covered individuals, including employees, their spouses, and dependents. These enrollees obtain health care under fee-for-service plans, full and partially capitated plans, preferred and exclusive provider organizations, point of service plans, indemnity plans, health maintenance organizations, and consumer-directed health plans (Adamson, Chang and Hansen 2008).

III. Methods

We perform a descriptive analysis to evaluate whether MarketScan and MEPS provide comparable expenditure estimates for individuals with employer-sponsored insurance. This population makes up 91% of enrollees in private insurance plans.

Our analytic files were constructed from the 2005 MEPS) and data on a similar population from MarketScan for 2005. We identified individuals with ESI coverage in the MEPS data as individuals who reported having had coverage at any point in the calendar year through their current or past job, or through their union. We include all the enrollees in the MarketScan database, since they all have ESI coverage. For both datasets, we excluded patients 65 and over, as this population is measured by other datasets. The final sample sizes included 15,300 MEPS respondents and 24.8 million individuals in the MarketScan sample, representing 165.05 million individuals with ESI coverage.

A. Enrollment

For each of the datasets, we created summary measures of enrollment using data from the enrollment files in the respective databases (the Full Year Consolidated Data File in MEPS and the Enrollment Summary file in the MarketScan data). We grouped enrollees into demographic groups for age, gender and region. The age and region variables from the MEPS are self-reported at various points of the year while those in the MarketScan data are only from the beginning of the 2005.

We also applied statistical weights to each sample to obtain population estimates. The MEPS data provides sample weights that take into account the complex sampling design of the survey making adjustments for survey nonresponse rates (Ezzati-Rice, Rohde and Greenblat 2000). There are similar weights available for the MarketScan data; those weights are formed by comparing enrollment by age, gender, and region groups in the MarketScan convenience sample to those in the MEPS. The age groups used in deriving the MarketScan weights were broader than those used in our study (0-18, 18-44, 45-64). So, although the weighted datasets should, by construction, give very similar enrollment counts for gender and region, we do not expect each dataset's population estimates for enrollment for very granular age groups to be very similar.

B. Expenditures

We calculated total expenditures by summing expenditures that were reported by respondents, and then verified with providers (MEPS), or that were associated with claims submitted by enrollees (MarketScan). We define expenditures as total gross payments to providers for services (rather than just out-of-pocket spending or the amount paid by the insurance company). We included service categories that would yield comparable total spending estimates from the two datasets: care at hospitals (inpatient, outpatient, and emergency room), office visits, and prescription drugs. Because not all enrollees had prescription drug coverage, the MarketScan data likely underreports drug spending. Inpatient care is self-reported in MEPS and identified in MarketScan as hospital care that involved a room and board charge. The inpatient care category is essentially acute care: the MEPS sampling frame excludes individuals residing in long-term care and the MarketScan data contain very few claims from long-term facilities.

IV. Study findings

A. Enrollment

Table 1 illustrates that sampling weights can be applied to convenience samples to obtain better population estimates. The first column of table 1 gives enrollment counts by demographic groups for the 24.8 million enrollees in the MarketScan sample; the second column does the same for the 15,300 individuals in the MEPS sample.

Table 1. Distribution of NonElderly Individuals Enrolled in ESI Plans, 2005 (Percent of Total).

| Number of Enrollees | Sample | ESI Population Estimates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| MarketScan | MEPS | MarketScan | MEPS | |

|

|

|

|||

| 24.8 mil | 15,300 | 165.1 mil | 165.0 mil | |

| 0 to 4 years | 7.1 | 6.4 | 6.9 | 6.4 |

| 5 to 17 years | 19.2 | 20.1 | 18.6 | 18.6 |

| 18 to 24 years | 9.9 | 8.7 | 9.4 | 8.8 |

| 25 to 44 years | 31.6 | 33.8 | 33.5 | 33.9 |

| 45 to 64 years | 32.3 | 30.9 | 31.5 | 32.3 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

|

| ||||

| Male | 48.2 | 49.1 | 50.1 | 50.1 |

| Female | 51.8 | 50.9 | 49.9 | 49.9 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

|

| ||||

| Northeast | 9.5 | 17.1 | 19.9 | 19.9 |

| Midwest | 20.2 | 21.8 | 23.8 | 23.7 |

| South | 45.4 | 36.5 | 34.0 | 34.1 |

| West | 24.9 | 24.5 | 22.3 | 22.3 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

The population estimates derived by applying the MarketScan weights are shown in the third column. The distribution of age groups was similar between the sample and estimated population (columns 1 and 3), but the gender and region distributions were quite different. The percent of enrollees that were female is about 50 percent in the population estimate, or two percent lower than the percent in the sample. The percentage of enrollees living in the South and West regions was lower in the population estimates (a combined 56 percent of enrollees) than in the sample (70 percent of the enrollees).

The MarketScan estimates for the distribution of enrollees in the population were very similar to those derived from the MEPS data (columns 3 and 4).

B. Expenditures

Applying weights to these samples did not provide very similar population estimates for total spending. Estimated total spending according to the MarketScan data was about 10 percent higher than that from the MEPS data ($453 billion and $408 billion, respectively). As shown in table 2, the differences were not uniform across demographic groups. For example, the MarketScan estimate of total spending by males was 15 percent higher than MEPS and 8 percent higher for females. These differences arose from differences in either the proportion of enrollees that were treated or the average expenditures for those patients.

Table 2. Differences in Spending for NonElderly Individuals Enrolled in ESI Plans, 2005.

| MarketScan | MEPS | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| (1)/(2) | |||

| 0 to 4 years | $20.8 | $14.4 | 1.44 |

| 5 to 17 years | $30.3 | $33.3 | 0.91 |

| 18 to 24 years | $19.8 | $17.3 | 1.14 |

| 25 to 44 years | $121.6 | $122.7 | 0.99 |

| 45 to 64 years | $260.4 | $220.2 | 1.18 |

|

| |||

| Total | $452.9 | $408.0 | 1.11 |

|

| |||

| Male | $251.9 | $233.1 | 1.08 |

| Female | $201.0 | $174.9 | 1.15 |

|

| |||

| Total | $201.0 | $174.9 | 1.15 |

|

| |||

| Northeast | $89.7 | $77.4 | 1.16 |

| Midwest | $122.4 | $112.2 | 1.09 |

| South | $162.1 | $132.5 | 1.22 |

| West | $78.6 | $85.9 | 0.92 |

|

| |||

| Total | $452.9 | $408.0 | 1.11 |

Note: All Estimates are Weighted

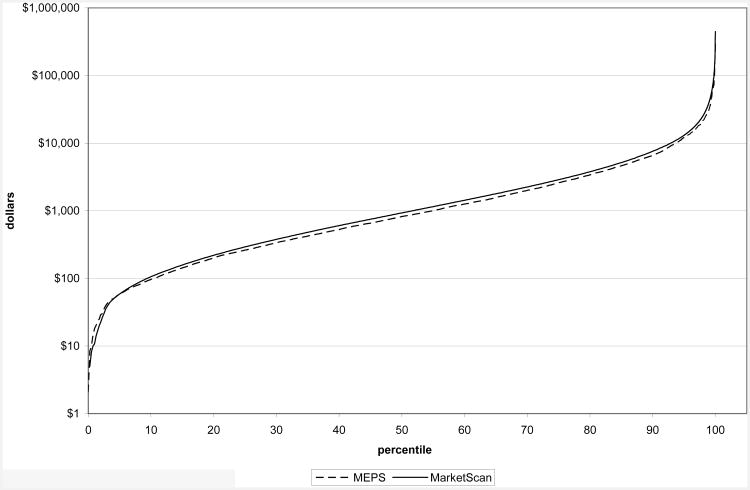

The per person spending distributions varied across the two data sources as well. The MarketScan estimate for mean annual per person spending was higher than that in MEPS: $2,740 (with a 95% confidence interval of $2735 to $2745) in MarketScan and $2,472 (with a 95% confidence interval of $2314 to $2629) in MEPS. Excluding enrollees with zero spending magnified the differences in mean spending to about $500 per patient (from less than $300 for per patient). The distribution of annual per person spending in each data source shown in Figure 1 demonstrates that these differences existed at most points in the distribution.

Figure 1. Distribution of Spending per Patient.

Note: Excludes enrollees with zero spending

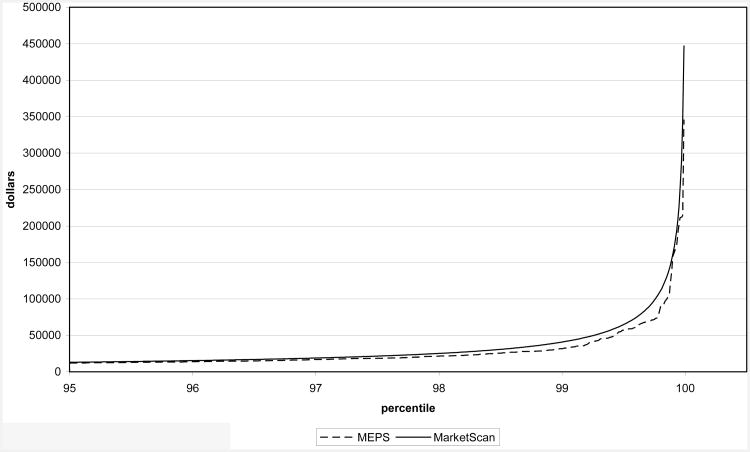

Focusing on the right tail of the distribution, in the MEPS data, the maximum annual spending per patient was around $345,000 dollars while the maximum spending per patient in the MarketScan data was $4 million dollars. Figure 2 shows the considerable differences across the two data sources in the distribution of spending in the top 5th percentile of spenders. The higher spending at the tail end of the distribution in the MarketScan data came from a relatively small number of patients (20,000, or less than 1% of the total) that had spending higher than the highest spender reported in the MEPS data: $345,882. When we excluded these high spenders from the claims data, mean per patient spending remained higher in the MarketScan data than in the MEPS data ($3,465 and $3,045, respectively).

Figure 2. Distribution of Spending per Patient, top 5th percentile.

Note: Excludes enrollees with zero spending

V. Discussion

We compared 2005 MEPS health expenditure estimates for people with employer-sponsored insurance to the spending estimates from 2005 MarketScan claims data for a large, convenience sample of individuals with ESI. We found that MEPS underestimated expenditures in the ESI population, particularly at the high end of the expenditure distribution. Truncating the MarketScan spending distribution, the differences narrowed somewhat but MEPS continued to underestimate spending relative to MarketScan, suggesting that there is also some ‘across the board’ underreporting of service use (and associated expenditures) in MEPS. This persistent deviation is despite a likely undercount in the MarketScan data for prescription drugs (since not all enrollees had drug coverage).

Our finding that MEPS underestimates annual expenditures for individuals with ESI is consistent with past research demonstrating MEPS' underestimation of spending on other populations, including non-institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries (Zuvekas and Olin 2009b; Zuvekas and Olin 2009a) and Medicaid enrollees (Mark et. al. 2003). More broadly, these findings are consistent with MEPS' known underestimation of NHEA personal health expenditures (Selden et. al. 2001; Sing et. al. 2006). Further, as in these past studies, the results of the current study suggest that the underestimation of expenditures in MEPS is largely a function both of 1) underrepresentation of high expenditure cases, and 2) underestimation of spending on the remaining covered lives.

The striking underrepresentation of high cost spenders in MEPS is likely due to multiple factors.3 While the MEPS sampling frame excludes individuals residing in long-term care facilities, MEPS respondents living in the community can be institutionalized subsequent to their entry into the MEPS sample. Yet, those MEPS respondents who leave the community for a health care institution (as well as other institutions) suspend their medical care utilization and expenditure reporting while institutionalized. Respondents who eventually return to the community are again eligible for participation and resume reporting medical utilization and spending (Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research 2005). Still, a vast gap in these individuals’ spending remains. Hospital expenditures may also be underestimated because MEPS treats hospitalizations longer than 45 days as an institutional stay, resulting in the exclusion from MEPS of the costs of these prolonged hospitalizations (Sing 2006). In turn, for high cost individuals who are included in MEPS, total expenditures may be underestimated due to under-reporting of spending in the setting of major health changes. For example, the survey may miss some of the high cost expenditures that occur just before a sampled person dies or is institutionalized. Finally, there is some evidence that individuals using such services as renal dialysis clinics, outpatient alcohol treatment, and family planning centers, are not only underreported by households, but these households are not likely to be surveyed at all (Selden et al 2001). To the extent these are high cost patients (certainly, dialysis patients are), this will further reduce the representation of high cost individuals in MEPS.

Even after accounting for the poor capture of very high cost patients, MEPS underestimates spending relative to MarketScan data.4 These differences could be caused by several different factors. The accuracy of survey estimates are inseparably linked to the underlying survey design and response rates; errors may arise from sampling bias, non-response bias, attrition, and any of a number of other measurement errors (Cohen 2003). Underreporting of health services utilization is also a matter of import. A recent review of 42 studies identified underreporting as the most common problem affecting the accuracy of self-reported utilization data (Bhandari and Wagner 2006). While MEPS has the Medical Provider and Pharmacy Components to verify household reported costs, it does not use these components to verify the quantity of services utilized; the household reports are the sole source of quantity data, and underreported quantities will miss the corresponding spending (Zuvekas and Olin 2009b).

MEPS may underestimate spending to a greater degree in some service categories than others. For example, laboratory studies are one such source of underestimation. MEPS captures expenditures for laboratory studies billed by physicians offices and outpatient care centers. However, laboratory services that are billed independently - by the laboratories themselves – are not captured in MEPS (Selden et. al. 2001). In addition, due to complex payment structures and third-party payers, household reports are likely to be inaccurate and surveys of providers and pharmacies do not cover all services, requiring costs to be imputed for certain services. As with any imputation, this presents problems of both random and nonrandom error in the expenditure data (Zuvekas and Olin 2009b).

This study had some limitations of note. First, while we attempted to make the MEPS and MarketScan ESI populations as comparable as possible, some differences may have remained. MEPS is a relatively small sample, but should be nationally representative once weights are applied to account for sample design and nonresponse rate. The enrollee counts in the MarketScan data can also be made representative by applying weights; however, some notable differences remained in the weighted data. The age profiles of the MarketScan-based population estimates differed somewhat from those from the MEPS. Further, a lower proportion of MarketScan enrollees submitted claims than in MEPS (78% versus 81%).5 Our findings beg the question of how best to combine the power (or sample size) of the MarketScan claims databases with the representativeness of the MEPS household surveys. If differences between the two data sources were uniform across the distribution of spending, statistical adjustments could readily be made to correct the expenditures in both. However, the expenditure differences are substantially greater at the high end of the spending distribution and more work will be needed to assess the consistency across the remaining distribution.

VI. Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that, for individuals with employer-sponsored insurance, MEPS underestimates health care expenditures relative to MarketScan. This appears to be a result of underrepresentation of high cost spenders, as well as a more general underestimation of spending across the distribution of health care expenditures in MEPS. With the rapid pace of change in the financing and delivery of health care, the demand for more clinically-nuanced measures of health care productivity will be critical for policymaking and planning. To provide these estimates, statistical agencies will increasingly rely on different sources of national expenditure data. The increased sample size provided by MarketScan data will allow for more clinically detailed expenditure estimates, however, the differences between this proprietary claims database and the comparable population in MEPS suggest the need for additional research focused on reconciling key differences.

Table 3. Mean Annual Spending for ESI Enrollees, 2005.

| MarketScan | MEPS | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Enrollees in Sample | 24.8 mil | 15,300 |

|

| ||

| Estimated Population | 165.1 mil | 165.0 mil |

| Percent with Spending | 71.5% | 80.8% |

|

| ||

| Mean Annual Spending | ||

| All Enrollees | $2,740 | $2,472 |

| Enrollees with nonzero spending | $3,568 | $3,045 |

| Truncated spending* | $3,465 | $3,045 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

Spending is truncated at highest MEPS expenditure.

Footnotes

Estimate is current as of 2008 and is for people ages 18-64. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/hinsure.htm

MarketScan User Guide: National Weights (White Paper)

A very similar problem arises when forming estimates for wealth, another variable with a highly skewed distribution. Kennickell (2007) showed summary measure of wealth derived from the Survey of Consumer Finances administered by the Federal Reserve Board were significantly improved by their oversampling of wealthy households.

A similar problem arises with other expenditure surveys. See Garner, Janini, Passero, Paskiewicz and Vendemia (2006) for a discussion of the issues in the context of the Consumer Expenditure Survey administered by the Bureau of Labor Statistics

Some of this difference might be explained by lack of prescription drug coverage for patients in the MarketScan sample.

References

- Adamson DM, Chang S, Hansen LG. Health Research Data for the Real World: The MarketScan Databases. Thomson Healthcare; Jan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. MEPS-HC-097: 2005 Full Year Consolidated File. Center for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends; Rockville, MD: Nov, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aizcorbe A, Nestoriak N. Changes in Treatment Intensity, Treatment Substitution, and Price Indexes for Health Care Services. National Bureau of Economic Research Productivity Workshop; Cambridge, MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aizcorbe A, Retus B, Smith S. Toward a Health Care Satellite Account. Survey of Current Business. 2008 May;88:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-Reported Utilization of Health Care Services: Improving Measurement Accuracey. Medical Care Research and Review. 2006;63:217–235. doi: 10.1177/1077558705285298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R, Cardenas E, Ginsburg DH, Rozental L, Velez F. Producing disease-based price indexes. Monthly Labor Review. 2010 Feb;:20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JW, Cohen SB, Banthin JS. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: A National Information Resource to Support Healthcare Cost Research and Inform Policy and Practice. Medical Care. 2009 Jul;47:S44–S50. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a23e3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SB. Design Strategies and Innovations in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Medical Care. 2003;41:III5–III2. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000076048.11549.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SB, Wun LM. A comparison of household and medical provider reported health care utilization and an estimation strategy to correct for response error. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement. 2005;30:115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Rosen AB, Vijan S. Value of Medical Innovation in the United States: 1960-2000. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006:920–927. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WN, Levy H, Simon KI. Data Watch Research in Health Economics. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2000 Autumn;14:203–216. doi: 10.1257/jep.14.4.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati-Rice T, Rohde F, Greenblatt J. Sample Design of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component, 1998-2007. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Mar, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garner TI, Janini G, Passero W, Paszkiewicz L, Vendemia M. The CE and the PCE: a comparison. Monthly Labor Review. 2006 Sep;:20–46. [Google Scholar]

- Heffler S, Nuccio O, Freeland M. An Overview of the NHEA With Implications for Cost Analysis Researchers. Medical Care. 2009;47:S37–S43. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a4f46a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennickell AB. The Role of Over-sampling of the Wealthy in the Survey of Consumer Finances. Federal Reserve Board; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Machlin S, Cohen J, Elixhauser A, Beauregard K, Steiner C. Sensitivity of Household Reported Medical Conditions in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Medical Care. 2009;47:618–625. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318195fa79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie C, editor. Strategies for a BEA Satellite Health Care Account: Summary of a Workshop. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2009. Pages. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Levit KR, Buck JA, Coffey RM, Vandivort-Warren R. Mental Health Treatment Expenditure Trends, 1986-2003. Psychiatric Services. 2007 Aug;58:1041–1048. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.8.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen AB, Cutler DM. Measuring Medical Care Productivity: A Proposal for the US National Health Account. Survey of Current Business. 2007;87:54–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen AB, Cutler DM. Reconciling National Health Expenditure Accounts and cost-of-illness studies. Medical Care. 2009 Jul;47:S7–S13. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a23e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen AB, Bondarenko I, Messer K, Raghunathan T, Cutler DM. Measuring Chronic Disease Prevalence in the US Elderly: A Comparison of Two National Expenditure Surveys [Google Scholar]

- Selden TM, Levit KR, Cohen JW, Zuvekas SH, Moeller JF, McKusick D, Arnett RH. Reconciing Medical Expenditure Estimates from the MEPS and NHA, 1996. Health Care Financing Review. 2001 Fall;23:161–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensenig A, Wilcox E. National Health Accounts/National Income and Product Accounts Reconciliation -- Hospital Care and Physician Services. In: Cutler DM, Berndt ER, editors. Medical Care Output and Productivity. University of Chicago Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research; Chicago: 2001. pp. 271–302. [Google Scholar]

- Sing M, Banthin JS, Seldin TM, Cowan CA, Keehan SP. Reconciling Medical Expenditure Estimates from the MEPS and NHEA, 2002. Health Care Financing Review. 2006 Fall;28:25–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Marder WD, Houchens R, Conklin JE, Bradley R. Can A Disease-Based Price Index Improve the Estimation of the Medical Consumer Price Index? In: Diewert WE, et al., editors. Price Index Concepts and Measurements. The University of Chicago Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research; Chicago: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton MW. The High Concentration of US Health Care Expenditures. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Jun, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH, Olin GL. Validating Household Reports of Health Care Use in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Health Services Research. 2009a Oct;44:1679–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH, Olin GL. Accuracy of Medicare Expenditures in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Inquiry. 2009b Spring;46:92–108. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_46.01.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]