Abstract

Statement of Problem

Even though high precision technologies have been used in computer-guided implant surgery, studies have shown that linear and angular deviations between the planned and placed implants can be expected.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of operator experience on the accuracy of implant placement with a computer-guided surgery protocol.

Material and Methods

Ten surgically experienced and 10 surgically inexperienced operators participated in this study. Each operator placed 1 dental implant (Replace Select) on the partially edentulous mandibular model that had been planned with software by following a computer-guided surgery (NobelGuide) protocol. Three-dimensional information of the planned and placed implants were then superimposed. The horizontal and vertical linear deviations at both the apex and platform levels and the angular deviation were measured and compared between the experienced and inexperienced groups with the independent t test with Bonferroni adjustment (α=.01). The magnitude and direction of the horizontal deviations were also measured and recorded.

Results

No significant differences were found in the angular and linear deviations between the 2 groups (P>.01). Although not statistically significant (P>.01), the amount of vertical deviation in the coronal direction of the implants placed by the inexperienced operators was about twice that placed by the experienced operators. Overall, buccal apical deviations were most frequent and of the highest magnitude.

Conclusion

When a computer-guided protocol was used, the accuracy of the vertical dimension (depth of implant placement) was most influenced by the operator’s level of experience.

INTRODUCTION

Proper implant position is fundamental to an esthetic and functional implant-supported restoration. Therefore, the implant must be placed accurately according to the treatment plan. A radiographic template in conjunction with cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) is considered a standard tool in dental implant diagnosis and treatment planning.1 Once proper planning is accomplished, the radiographic template can be manually converted to a surgical template to be used during implant placement surgery. However, while the manual conversion of radiographic to surgical templates is reasonably effective, it is subjective, as the accuracy of the surgical template cannot be verified radiographically.

Computer-guided surgery uses computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) technology in conjunction with CBCT.2,3 With this technique, implant planning is done digitally, and the relationship between the implant position and radiographic template can be used to fabricate a stereolithographic surgical template.2,3 The precision guide incorporated into the surgical template allows the clinician to place the implant in the planned position more accurately than when using a non-CAD/CAM surgical guide.4 Even though high precision technologies are used in such processes, studies have shown that some linear and angular deviations between the planned and placed implants can be expected.5–12 However, the effect of the clinician’s level of experience on the accuracy of implant placement with a computer-guided surgery protocol has not been reported.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the accuracy of computer-guided dental implant placement with CBCT and to determine whether the operator’s level of experience had an effect on the accuracy of implant placement with a computer-guided surgery protocol. The null hypotheses for this study were that no angular and linear (horizontal and vertical) deviations would be found between the planned and placed implant positions with a computer-guided surgery protocol and that the magnitudes of angular and linear (horizontal and vertical) deviations, if present, would not be affected by the operator’s level of experience.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Loma Linda University and was conducted at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry, Calif. Ten inexperienced operators were recruited from the third year student dentists, who received classroom lectures on implant dentistry but did not have any experience in making implant osteotomy or placing dental implants. The 10 experienced operators comprised the graduate students and fellows in the Advanced Education in Implant Dentistry Program, who had placed more than 20 implants. The operators consented to participation in this study.

Drillable/surgical polyurethane mandibular models with radiopaque teeth from left to right first molars with the edentulous spaces on the second premolars bilaterally were fabricated (Paradigm Dental Models) (Fig. 1). The radiographic guide for planning implants in the mandibular second premolar spaces was fabricated from clear acrylic resin (Orthodontic Resin; Harry J Bosworth Co) with 6 radiopaque markers (Dental Stopping; Coltène/Whaledent Inc) according to the NobelGuide System’s protocol (Nobel Biocare) (Fig. 2). Double CBCT scans (radiographic guide only and model with radiographic guide) were made (i-CAT; Imaging Sciences Intl). A NobelGuide calibration object (Nobel Biocare) had been previously scanned and used as the reference scan so that the correct isovalue of the radiographic guide scan could be identified. Digital imaging and communication in medicine (DICOM) files of the CBCT images were transferred to the NobelGuide software, where 2 implants were planned at the left and right mandibular second premolar positions. The planned implants were NobelReplace Tapered Groovy RP 4.3×13 mm implants (Nobel Biocare) (Fig. 3). This information was used to fabricate the stereolithographic surgical template (Fig. 4). The surgical template, in conjunction with the NobelGuide Surgical System, was used during the osteotomy and placement of the mandibular second premolar implants.

Fig. 1.

Partially edentulous (missing second premolars bilaterally) mandibular model with radiopaque teeth.

Fig. 2.

Radiographic guide made of clear acrylic resin.

Fig. 3.

Planning of implant position with NobelGuide software A, Buccolingual view. B, Mesiodistal view.

Fig. 4.

Stereolithographic surgical template.

The mandibular model was firmly attached to a customized base that could be assembled with the maxillary typodont. The customized typodont assembly was then mounted on a mannequin head to simulate an intraoral situation (Fig. 5). A step-by-step sequence of computer-guided surgery was verbally and visually (by means of a computer presentation) explained to each operator (Figs. 6–8). Each operator placed 1 dental implant with a computer-guided surgery (NobelGuide) protocol. For each model, implants on the left and right mandibular second premolars were placed by an experienced and an inexperienced operator in a randomized (coin toss) but equally distributed fashion. Therefore, the left and right mandibular second premolar implants were both placed by 5 experienced and 5 inexperienced operators. The models, with the original radiographic guide in place, were then rescanned with CBCT (i-CAT).

Fig. 5.

Mandibular model with maxillary typodont mounted on mannequin head to simulate intraoral situation.

Fig. 6.

Sequential osteotomy. A, Note flange on drill. B, Flange in contact with metal sleeve of surgical template to control depth of osteotomy.

Fig. 7.

A, Initial implant placement with surgical handpiece. B, Final implant placement with manual torque wrench at ≤ 45 Ncm.

Fig. 8.

Occlusal view of implants in position.

The DICOM files of the planned and placed implant were transported to NobelGuide Validation Software Version 2.0.0.4 (Nobel Biocare c/o Medicim NV) for 3-dimensional (3D) superimposition and measurement. The superimposition was performed with an automatic matching procedure based on multimodality image registration by maximizing the mutual information of the planned and placed 3D images (Fig. 9). The 3D coordinates of the centers of the platform and the apex of the planned and placed implants were then determined and used to measure the angular and linear deviations between the planned and placed implants.

Fig. 9.

Three-dimensional superimposition of planned (yellow) and placed (light blue) implants.

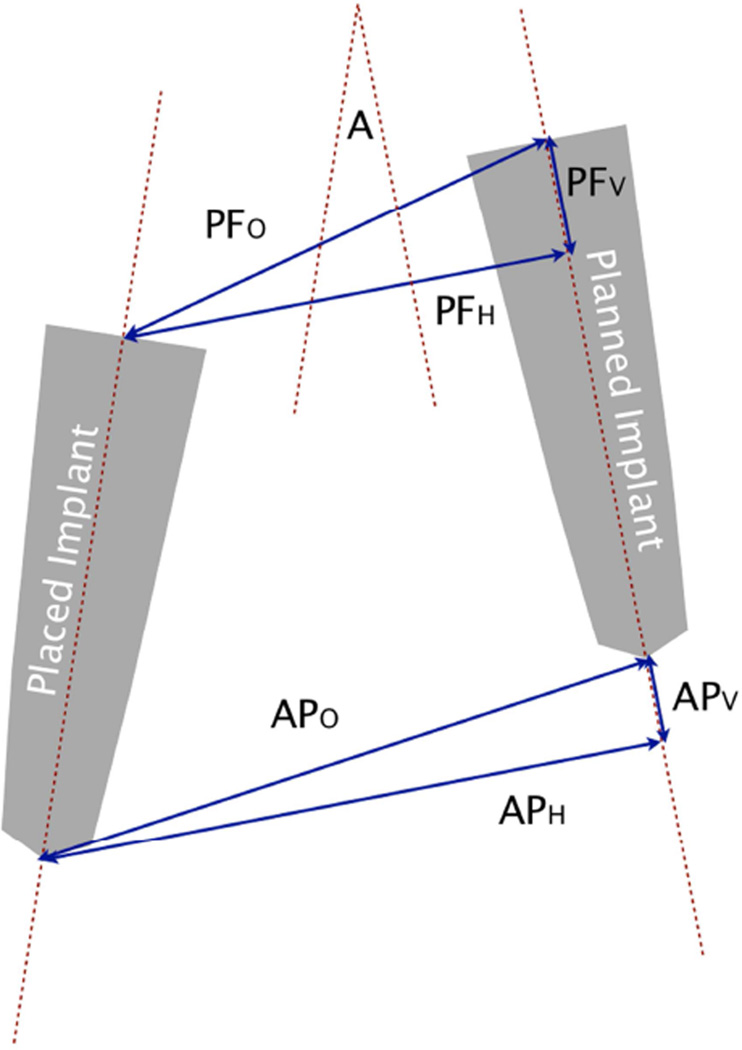

The linear and angular deviations of the respective planned and placed implants were measured and recorded as shown in Figure 10. The vectors (Mesial-Distal [M-D] and Buccal-Lingual [B-L]) of the horizontal deviations at both the platform and apex levels were also recorded. All linear and angular deviations were compared between the experienced and inexperienced groups with the independent t test with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple testing (α=.01).

Fig. 10.

Measurements of linear and angular deviations between planned and placed implants.

A: Angular deviation between planned and placed implants

PFO: Overall deviation at implant platform level

PFH: Horizontal deviation at implant platform level

PFV: Vertical deviation at implant platform level

APO: Overall deviation at implant apex level

APH: Horizontal deviation at implant apex level

APV: Vertical deviation at implant apex level

RESULTS

The means and standard deviations of the linear and angular deviations of the experienced and inexperienced groups are presented and compared in Table 1. No significant differences were found in the angular and linear deviations between the 2 groups (P>.01; Table 1). The distributions of the M-D and B-L deviations at the platform and apex level are shown in Figures 11 and 12.

Table 1.

Comparison of angular and linear deviations between experienced and inexperienced groups using independent t test with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple testing (α=.01)

| Mean ± SD deviation between planned and placed implants | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Experienced (n=10) | Inexperienced ( n=10) | P | |

| A (degree) | 4.11 ± 0.76 | 3.21 ± 1.99 | .196 |

| PFO (mm) | 0.47 ± 0.15 | 0.64 ± 0.21 | .049 |

| PFH (mm) | 0.36 ± 0.13 | 0.37 ± 0.21 | .861 |

| PFV (mm) | −0.23 ±.22 | −0.49 ± 0.21 | .015 |

| APO (mm) | 1.32 ± 0.25 | 1.22 ± 0.63 | .617 |

| APH (mm) | 1.28 ± 0.24 | 1.07 ± 0.66 | .348 |

| APV (mm) | −0.26 ± 0.23 | −0.51 ± 0.21 | .019 |

A: Angular deviation between planned and placed implants

PFO: Overall deviation at implant platform level

PFH: Horizontal deviation at implant platform level

PFV: Vertical deviation at implant platform level

APO: Overall deviation at implant apex level

APH: Horizontal deviation at implant apex level

APV: Vertical deviation at implant apex level

Fig. 11.

Overall frequency distribution of horizontal deviation in mesiodistal direction. M = mesial; D = distal.

Fig. 12.

Overall frequency distribution of horizontal deviation in buccolingual direction. B = buccal; L = lingual.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study support the rejection of the null hypothesis that stated that no angular and linear (horizontal and vertical) deviations would be found between the planned and placed implant position. However, the results of this study support the acceptance of the null hypothesis that stated that the angular and linear deviations would not be affected by the operator’s level of experience (P>.01) (Table 1).

Studies have revealed inherent errors in computer-guided implant surgery systems that result in inaccurate implant placement.5–9 Besides the surgical errors during the implant placement, inaccuracy can be compounded by the errors accumulated during CT image acquisition and data processing,10 stereolithographic surgical template production,11 and the tolerance of the guiding sleeve.12 A systematic review of the accuracy of computer-guided implant surgery has reported mean linear deviations of 1.07 mm at the entry point and 1.63 mm at the apex, a mean height deviation of 0.43 mm, and a mean angular deviation of 5.26 degrees.5 The results of this study (mean linear deviations of 0.36 to 0.64 mm at the platform level and 1.07 to 1.32 mm at the apex, mean height deviations of 0.23 to 0.51 mm, and mean angular deviations of 3.21 to 4.11 degrees [Table 1]), are within the range of the reported data and comparable with the mean values from the studies where the surgical templates were supported by teeth (mean linear deviations of 0.84 mm at the entry point and 1.20 mm at the apex and a mean angular deviation of 2.82 degrees).5–8 As a certain degree of deviation can be expected with computer-guided implant surgery, a periodic verification of the osteotomy should be practiced during implant surgery, especially when there are risks of violating vital structures.

In this study, no significant differences were found in the angular and linear deviations between the experienced and inexperienced operators (P>.01; Table 1). These results suggest that both groups are similarly prone to the errors inherent in the computer-guided system, regardless of the experience level. Almost all implants (95%) were placed more coronally than the planned position. As the depth/vertical position of the osteotomy/implant is controlled by the contact between the flange of the drill/implant mount and the guiding sleeve of the surgical template (Figs. 6, 7), angular deviation would cause the premature contact of the surfaces, resulting in a more coronally placed implant position than the planned implant position. Though not statistically significant (P>.01 [Table 1]), the fact that the amount of vertical deviation (PFV and APV [Table 1]) in the coronal direction of the implants placed by the inexperienced operators was about twice that placed by the experienced operators implies that the inexperienced operators might be more cautious and/or less certain about the implant depth than the experienced group. Nevertheless, these results suggest that the vertical position control of the computer-guided system provides adequate safety features, as most of the errors were in the coronal direction; therefore, the risk of encroaching on vital structures (such as inferior alveolar nerve, maxillary sinus) is minimal. However, coronally placed implants might compromise the prosthetic emergence profile. In such circumstances, the definitive vertical implant position should be verified to ensure satisfactory esthetic results.

When evaluating the direction of horizontal linear deviation, it was observed that at both platform and apex levels, the deviations were mostly in the mesial (85% [Fig. 11]) and buccal (85–90% [Fig. 12]) directions. At platform level, most of the deviations were within 0.5 mm in both M-D (90%) and B-L (95%) directions. However, at apex level, the deviations were within 0.5 mm in M-D direction 60% of the time, whereas only 30% were observed in B-L direction (Fig. 11, 12). Greater than 1.0 mm deviations were observed more frequently in B-L (35%) than M-D (3/20=15%) directions (Fig. 11, 12). These results indicate that the buccal apical deviations are most frequent and of the highest magnitude.

Therefore, the buccal bone available must be taken into consideration when computer-guided implant surgery is planned. Nonetheless, this study was performed in the posterior mandibular area, and so the results should only be applied to this specific area and not other areas in the mouth. Furthermore, even though the implants were placed in the model mounted to the mannequin head to simulate the intraoral situation, it did not take into account the limit of the maximum opening and the presence of the tongue, cheek, saliva, and/or blood in the clinical situation, which may compromise access and visibility during implant surgery. These limitations may contribute to the different magnitude and direction of the deviations. In vivo studies at multiple implant sites will provide more information regarding the effect of the experience level on the accuracy of computer-guided implant surgery.

This study only investigated the implant placement procedure and not other aspects of implant treatment, including proper diagnosis and treatment planning, surgical procedure (including soft and hard tissue management), and prosthodontic procedure. While the results of this study demonstrate that the differences in implant deviations between experienced and inexperienced operators using a computer-guided template were not significant, they by no means suggest that the inexperienced operators were as qualified as the experienced operators in performing implant procedures. However, the results seem to indicate that, with the inclusion of appropriate implant knowledge in the curriculum and under close supervision, an inexperienced operator (student dentist) may perform implant placement with computer-guided protocol.

CONCLUSIONS

Within the limitations of this study, the following conclusions can be made regarding computer-guided implant surgery:

A certain degree of angular and linear deviations can be expected between the planned and placed implants.

No significant differences were found in the angular and linear deviations between the experienced and inexperienced operators (P>.01).

Though not statistically significant (P>.01), the amount of vertical deviation in the coronal direction of implants placed by inexperienced operators was about twice that placed by experienced operators.

The buccal apical deviations were most frequent and of the highest magnitude.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS.

The results indicate that, with the inclusion of appropriate implant knowledge in the curriculum and under close supervision, an inexperienced operator may perform implant placement with a computer-guided protocol.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Grenith Zimmerman for the statistical advice; and Dr. Pakawat Chatriyanuyoke, Dr. Petch Oonpat and Dr. Peder Nordberg for their contribution in the project.

This study was supported by NIH Grant #1 R 15 DE017625-01A1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kourtis S, Skondra E, Roussou I, Skondras EV. Presurgical planning in implant restorations: Correct interpretation of cone-beam computed tomography for improved imaging. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2012;24:321–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2012.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchack CB. An immediately loaded CAD/ CAM-guided definitive prosthesis: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;931:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarment D, Al-Shammari K, Kazor C. Stereolithographic surgical templates for placement of dental implants in complex cases. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2003;23:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noharet R, Pettersson A, Bourgeois D. Accuracy of implant placement in the posterior maxilla as related to 2 types of surgical guides: A pilot study in the human cadaver. J Prosthet Dent. 2014;112:526–532. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider D, Marquardt P, Zwahlen M, Jung RE. A systematic review on the accuracy and the clinical outcome of computer guided template-based implant dentistry. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20:73–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Giacomo GA, Cury PR, de Araujo NS, Sendyk WR, Sendyk CL. Clinical application of stereolithographic surgical guides for implant placement: preliminary results. J Periodontol. 2005;76:503–507. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozan O, Turkyilmaz I, Ersoy AE, McGlumphy EA, Rosenstiel SF. Clinical accuracy of 3 14 different types of computed tomographyderived stereolithographic surgical guides in implant placement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Assche N, van Steenberghe D, Guerrero ME, Hirsch E, Schutyser F, Quirynen M, et al. Accuracy of implant placement based on pre-surgical planning of three-dimensional cone-beam images: a pilot study. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:816–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettersson A, Kero T, Gillot L, Cannas B, Fäldt J, Söderberg R, et al. Accuracy of CAD/CAM-guided surgical template implant surgery on human cadavers: Part I. J Prosthet Dent. 2010;103:334–342. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(10)60072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy MS, Mayfield-Doahoo T, Vanderven FJ, Jeffcoat MK. A comparison of the diagnostic advantages of panoramic radiography and computed tomography scanning for placement of root-form dental implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1994;5:229–238. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1994.050406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Steenberghe D, Naert I, Andersson M, Brajnovic I, Van Cleynenbreugel J, Suetens P. A custom template and definitive prosthesis allowing immediate implant loading in the maxilla: a clinical report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2002;17:663–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Assche N, Quirynen M. Tolerance within a surgical guide. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21:455–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]