Abstract

Background

Stroke survivors represent a target population in need of intervention strategies to promote cognitive function and prevent dementia. Both exercise and recreational activities are promising strategies. We assessed the effect of a six-month exercise and recreation program on executive functions in adults with chronic stroke.

Methods

A six-month ancillary study within a multi-centre randomized trial. Twenty-eight chronic stroke survivors (i.e., ≥ 12 months since an index stroke) were randomized to one of two experimental groups: intervention (INT; n=12) or delayed intervention (D-INT; n=16). Participants of the INT group received a six-month community-based structured program that included two sessions of exercise training and one session of recreation and leisure activities per week. Participants of the D-INT group received usual care. The primary outcome measure was the Stroop Test, a cognitive test of selective attention and conflict resolution. Secondary cognitive measures included set shifting and working memory. Mood, functional capacity, and general balance and mobility were additional secondary outcome measures.

Results

Compared with the D-INT group, the INT group significantly improved selective attention and conflict resolution (p=0.02), working memory (p=0.04), and functional capacity (p=0.02) at the end of the six-month intervention period. Improved selective attention and conflict resolution was significantly associated with functional capacity at six months (r=0.39; p=0.04).

Conclusions

This is the first randomized study to demonstrate that an exercise and recreation program can significantly benefit executive functions in community-dwelling chronic stroke survivors who are mildly cognitively impaired – a population at high-risk for dementia and functional decline. Thus, clinicians should consider prescribing exercise and recreational activities in the cognitive rehabilitation of chronic stroke survivors.

Clinical Trial Registration

http://clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT01085240.

Keywords: Exercise, Socialization, Executive Functions, Chronic Stroke

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is the number one cause of neurological disability worldwide and is characterized by both cognitive and motor impairments which contribute to functional dependence and reduced quality of life. Critically, cerebrovascular disease – such as stroke – is the second most common cause of dementia (1). Specifically, having a stroke doubles one’s risk for dementia (2). Thus, stroke survivors represent a target population in need of intervention strategies to promote cognitive function and prevent dementia.

Impaired executive functions are one of the most common cognitive consequences of stroke; 19% to 75% of stroke survivors have impaired executive functions (3). Executive functions are higher order cognitive processes that include the ability to concentrate, attend selectively, plan, and strategize. Critically, executive functions play a significant role in determining functional recovery post-stroke (4,5). Thus, promoting executive functions post-stroke is of significant clinical importance.

Current evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that targeted exercise training –including aerobic exercise, resistance training, and balance exercises – is an effective strategy to promote executive functions in older adults (6–8). However, there is insufficient quality evidence for targeted exercise training as an effective strategy to promote cognitive function in stroke survivors (9–11) – especially among those with chronic stroke (i.e., ≥ 12 months since an index stroke). Yet, up to 30% of stroke survivors develop dementia or cognitive impairment 15 months post-stroke (12). To our knowledge, only one randomized controlled trial to date has been conducted to primarily examine the effect of targeted exercise training on cognitive function in this population (13).

Engagement in intellectual and social activities (e.g., Bridge, Charades, volunteering, etc.) may also promote cognitive function in chronic stroke survivors. This hypothesis is supported by evidence from both animal (14) and human studies (15,16). In a community-based cohort of 1203 non-demented individuals, Fratiglioni and colleagues (16) demonstrated that an extensive social network protects against dementia. Specifically, a poor or limited social network increased the risk of dementia by 60%.

We previously demonstrated that a six-month exercise and recreation program could promote executive functions in chronic stroke survivors (17). However, our previous work used a single group pre-test/post-test design and this is a significant limitation. This is also a key limitation of recent published studies examining the effect of targeted exercise training on cognitive function in chronic stroke survivors (18,19).

To extend our previous work, we conducted an ancillary proof-of-concept study within a Canadian multi-centre randomized trial aimed at enhancing life participation after stroke, known as “Getting On with the Rest of Your Life after a Stroke”. The primary objective of this multi-centre study was to determine the extent to which participation in life’s roles can be optimized through the provision of a community-based structured program providing the opportunity for physical activity, leisure, and social interaction. The primary objective of our ancillary study was to assess if an exercise and recreation program could significantly improve executive function in adults with chronic stroke compared with a delayed intervention group (i.e., control). Secondary outcomes measures of interest include mood, functional capacity, and general balance and mobility.

METHODS

Study Design

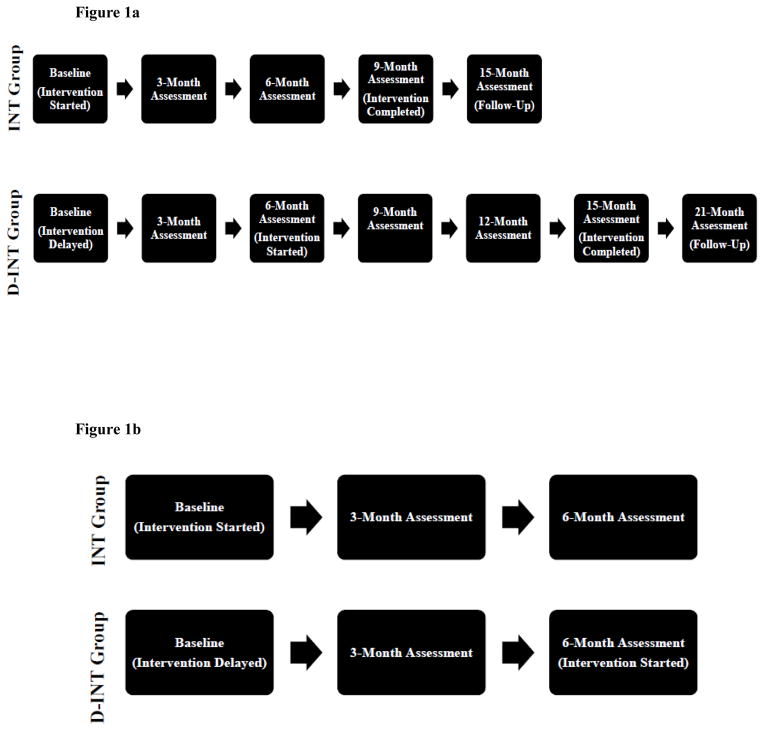

The “Getting On with the Rest of Your Life” study (http://clinicaltrials.gov; NCT01085240) had six Canadian study sites in total and used a randomized, single-blinded, cross-over design (Figure 1a). Specifically, participants were randomized to one of two experimental groups (i.e., intervention or delayed intervention). There was a six-month lag between the two experimental groups. For each experimental group, there was a nine-month intervention period with a six-month follow-up period (i.e., 15 months in total). Throughout the intervention period, assessments occurred every three months with blinded assessors. A single assessment occurred at the end of the six-month follow-up period. For our ancillary proof-of-concept study, we collected additional outcome measures from the University of British Columbia site and analyzed the data acquired from the first six months of the randomized trial (Figure 1b). We restricted our ancillary proof-of-concept study to the first six months because the delayed intervention group (i.e., wait-list control) began their intervention at that point in time.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Overall study design for “Getting On with the Rest of Your Life after a Stroke” (NCT01085240).

Figure 1b. Study design for ancillary proof-of-concept study.

Participants

We recruited participants through advertisements in local newspapers and community centers. We included those who: 1) had a single stroke greater ≥ 1 year onset and had completed their rehabilitation; 2) lived in their own home; 3) were aged ≥ 19 years and older; and 4) were able to walk > 10 meters independently (with or without walking aids). We excluded those could not safely participate in a physical activity program (e.g. serious cardiac disease).

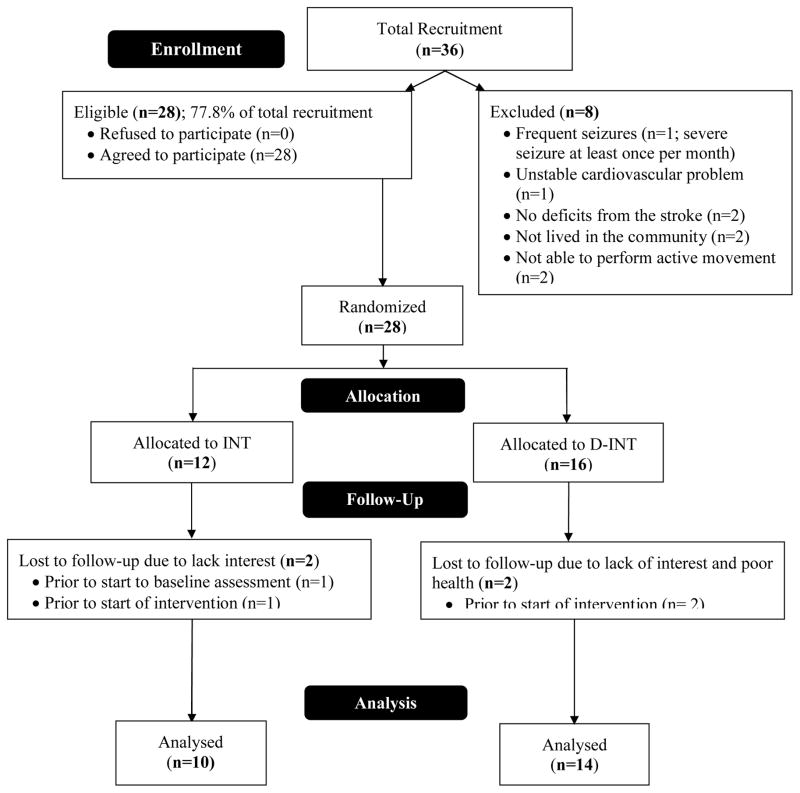

Figure 2, the CONSORT flow diagram, shows the number of participants in the treatment arms at each stage of the study. Ethical approval was obtained from the local university and hospital review boards. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Sample Size

We highlight this was a proof-of-concept study. However, we did calculate a sample size based on our previous work on exercise and cognitive function (7,17). We estimated the INT group will improve 10% on the Stroop Test, our primary measure of executive functions, while the DINT group will remain the same after six months. Assuming a common standard deviation of 32 for the mean change scores and a correlation of 0.90, 10 participants per group ensured a power of 0.70 (20).

Descriptive Variables

Global cognitive state was assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (21). The MoCA is a brief 30-point screening tool for mild cognitive impairment (21) with high sensitivity and specificity. Instrumental ADLs was assessed using the self-report Lawton and Brody (22) IADLs Scale. Type of stroke was determined by family physicians or participant’s hospital medical record.

Executive Functions

This study focused on three executive cognitive functions: selective attention and conflict resolution, set shifting, and working memory. We used the Stroop Test (23) to assess selective attention and conflict resolution and calculated the time difference between naming the ink colour in which the words were printed (while ignoring the word itself) and naming coloured Xs. Smaller time differences indicate better performance.

We used the Trail Making Tests (Part A & B) to assess set shifting (24); this test requires participants to draw lines connecting encircled numbers sequentially (Part A) or alternating between numbers and letters (Part B). The difference in time to complete Part B and Part A was calculated, with smaller difference scores indicating better performance.

We used the verbal digits forward and backward tests to index working memory (24). Participants repeated progressively longer random number sequences in the same order as presented (forward) and the reversed order (backward). Successful performance on the verbal digits span backward test represents a measure of central executive function due to the additional requirement of manipulation of information within temporary storage (25). Thus, we subtracted the verbal digits backward test score from the verbal digits forward test score to provide an index of working memory with smaller difference scores indicating better performance.

Mood

Depression is a prevalent clinical entity in the stroke population – it has been reported to be as high as 38% (26). We used the 17-item Stroke Specific Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (27) to assess for the presence of depression; a cut-off score of ≥ 6 has been suggested by the authors (personal communication).

Functional Capacity

We measured functional capacity using the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) (28), a walking test of physical status to assess general cardiovascular capacity in seniors. It is reliable and is related to other measures of walking ability and function that are commonly used during stroke rehabilitation (29). The total distance walked in six minutes was recorded.

Balance and Mobility

We measured general balance and mobility using the Berg Balance Scale (30) (BBS). The BBS is a 14-item test (maximum 56 points) and is a valid and reliable measure of functional balance (31).

Randomization

Participants were enrolled and randomised by the Research Coordinator using concealed allocation to one of two experimental groups: immediate intervention (INT; n=12) or delayed intervention (D-INT; n=16). The D-INT group started the community-based structured program six months after the INT group (Figure 1A). Participants of the D-INT group received usual care for the first six months of the study.

Intervention

The community-based structured program included two sessions per week focusing on resistance, balance, and aerobic exercise training. The exercises conducted were based on the FAME program (32), which has proven to be beneficial for individuals with stroke. Each session was 60 minutes in duration and was led by certified fitness instructors.

In addition to the exercise training sessions, participants attended an additional hour of recreation and leisure activities per week. A recreation programmer provided the recreation and leisure program. The recreation and leisure sessions included social activities as well as specific group activities that emphasize planning, strategy, decision making, and learning, such as playing billiards, bowling, arts and crafts, and cooking. Attendance was recorded daily by the assistants. Compliance, expressed as the percentage of the total classes attended, was calculated from these attendance sheets.

Adverse Effects

Participants were questioned about the presence of any adverse effects, such as musculoskeletal pain or discomfort, at each exercise session. All instructors also monitored participants for symptoms of angina and shortness of breath during the exercise classes.

Data Analysis

All analyses were “full analysis set” (33) (defined as the analysis set which is as complete and as close as possible to the intention-to-treat ideal of including all randomized participants). Descriptive data are reported for variables of interest. Data were analyzed using SPSS Windows Version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and Matlab Version 7.6 (Mathworks). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess for normal distribution among the outcome variables of interest. Non-parametric tests were used when variables were not normally distributed.

All three measures of executive functions and BBS were not normally distributed. Thus, the Kolmogrov-Smirnov Z test was applied to statistically test for significant between-group differences in the changes scores of these measures at three and six months. The Kolmogrov-Smirnov two-sample test has greater statistical power than the Mann-Whitney test when the study samples are small (34).

Both mood and functional capacity were normally distributed. Thus, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to statistically test for significant between-group differences, with baseline scores as covariates.

Finally, Pearson correlations were computed to determine whether changes in executive functions were related to functional capacity and BBS at six months. The overall alpha was set at p≤0.05.

RESULTS

Participants and Compliance

Three participants dropped out post randomization but prior to baseline assessment (Figure 2). Of the 25 participants who were randomized and completed baseline assessment, one participant dropped out of the INT group. Thus, 24 participants completed this 15-month randomized crossover study. Baseline demographic and characteristics of the 25 participants are shown in Table 1. With the exception for height (p=0.01), there were no significant differences between the two groups (p≥0.20). Based on the mean MoCA and GDS scores, our participants were mildly cognitive impaired and were borderline depressed. Based on the BBS scores, the participants in the INT-group were at risk for falls (35). Compliance for the INT group was 83% over the six-month period.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants (N=25).

| Variable* | INT (n=11) Mean (SD) |

D-INT (n=14) Mean (SD) |

Total (N=25) Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 62.9 (12.1) | 66.9 (9.0) | 65.2 (10.4) |

| Height (cm) | 163.5 (9.9) | 175.5 (9.2)‡ | 169.8 (11.1) |

| Weight (kg) | 75.7 (16.3) | 83.0 (17.0) | 80.0 (16.7) |

| MoCA Score (max. 30 pts) | 24.8 (2.6) | 21.8 (6.9) | 23.0 (5.6) |

| Time Since Stroke (yr) | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.9 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.1) |

| IADLs (max. 8 pts) | 5.9 (2.7) | 4.6 (1.8) | 5.2 (2.3) |

| Sex - Male† | 4 (36.3) | 11 (78.6) | 15 (60.0) |

| Ischemic Strokes† | 6 (54.5) | 9 (64.3) | 14 (56.0) |

| Hemorrhage Strokes† | 5 (45.5) | 5 (35.7) | 10 (40.0) |

| Affected Side - Right† | 4 (36.4) | 7 (50.0) | 11 (44.0) |

MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living (Lawton and Brody IADLs Scale).

Count = number of “yes” cases within each group. (%) = percent of “yes” within each group.

Significantly different between the two groups (p=0.01).

Executive Functions, Mood, Functional Capacity, and BBS

Table 2 reports the data for all outcome measures of interest. The results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test revealed a significant between-group difference in set shifting performance at three months (p=0.03). At the end of the six-month intervention period, there were significant between-group differences in both selective attention and conflict resolution (p=0.02) and working memory (p=0.04). There were no significant between-group differences in BBS (p≥0.92).

Table 2.

Mean values (SDs) for outcome measures.

| Variable* | Baseline Mean (SD) |

3-Month Mean (SD) |

6-Month Mean (SD) |

Mean 6-Month Change† Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INT | n=11 | n=10 | n=10 | n=10 |

| Stroop CW – Stroop C (sec)‡ | 85.3 (63.8) | 85.6 (100.5) | 60.8 (34.8) | 24.6 (33.6)** |

| Trail B – Trail A (sec) | 63.6 (32.4) | 53.5 (37.2) | 63.2 (41.5) | 0.4 (52.8) |

| Digit Forward – Digit Backward‡‡ | 4.9 (2.0) | 5.0 (2.5) | 2.8 (2.4) | 2.1 (1.1)** |

| Geriatric Depression Scale | 5.5 (4.4) | 2.4 (2.6) | 2.9 (4.9) | 2.6 (6.5) |

| Berg Balance Test (max. 56 pts) | 48.2 (8.2) | 48.6 (8.1) | 48.9 (7.8) | −1.3 (1.5) |

| 6-Minute Walk Test (m)# | 330.5 (174.4) | 343.1 (165.9) | 363.3 (173.4) | −44.5 (48.6)** |

| D-INT | n=14 | n=14 | n=14 | n=14 |

| Stroop CW – Stroop C (sec)‡ | 82.5 (68.2) | 85.4 (91.0) | 75.4 (78.3) | 6.7 (34.1) |

| Trail B – Trail A (sec) | 58.4 (57.8) | 65.8 (41.3) | 87.3 (59.8) | −28.9 (49.2) |

| Digit Forward – Digit Backward‡‡ | 5.6 (3.2) | 6.3 (2.6) | 4.7 (3.0) | 0.92 (2.7) |

| Geriatric Depression Scale | 5.8 (4.6) | 4.1 (2.7) | 3.9 (3.2) | 1.9 (5.6) |

| Berg Balance Test (max. 56 pts) | 41.1 (12.9) | 43.5 (13.5) | 42.9 (12.9) | −1.8 (3.5) |

| 6-Minute Walk Test (m)# | 254.2 (168.0) | 253.1 (167.7) | 272.7 (172.8) | −3.0 (26.0) |

Stroop CW = Stroop colour-words condition; Stroop C = Stroop coloured-X’s condition; sec = seconds; m = meters.

Significantly different from the D-INT group at p<0.05.

Mean change = baseline value minus final value. Positive value indicates improvement except for Geriatric Depression Scale and 6-Minute Walk Test.

INT baseline n=10, 3-month n=9, 6-month n=9; D-INT baseline n=12, 3-month n=13, 6-month n=12.

INT baseline n=10, 3-month n=9, 6-month n=9; D-INT baseline n=14, 3-month n=13, 6-month n=13.

INT baseline n=11, 3-month n=10, 6-month n=10; D-INT baseline n=14, 3-month n=13, 6-month n=14.

The results of the ANCOVA indicated no significant between-group differences in mood at three and six months (p≥0.14). However, there was a significant between-group difference in functional capacity at six months (p=0.02).

Improvement in selective attention and conflict resolution over the six-month intervention period was significantly associated with functional capacity at six months (r=0.39; p=0.04).

Adverse Events

No significant adverse events were reported by the INT group throughout the six-month intervention period. Only mild complaints were reported and they all resolved within two weeks of onset.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial to demonstrate that an exercise and recreation program can significantly benefit executive functions in community-dwelling chronic stroke survivors who are mildly cognitively impaired – a population at high-risk for dementia and functional decline.

Our current finding concurs with and extends our previous work (17). Specifically, using a single group pre-test/post-test design, we previously demonstrated that six months of exercise and recreation program significantly improved Stroop Test performance by 7% among 11 chronic stroke survivors (17). In the current study, we found a 29% improvement in task performance after six months. This exceeds the magnitude of benefit observed in previous studies with healthy community-dwelling older adults (11% to 13% improvement in selective attention and conflict resolution) (7,36) and older adults with mild cognitive impairment (17% improvement) (37). Furthermore, we observed a significant 43% improvement in working memory among participants in the INT group compared with those in the D-INT group.

The greater and broader benefit observed in this study may be related to participant characteristics. In our current study, there were seven females and four males in the INT-group. Our previous study included three females and seven males (17). A previous meta-analysis indicated that studies with more females than males have a greater effect size compared with studies with more males than females (0.60 vs. 0.15) (6).

To date, Quaney and colleagues (13) published the only randomized controlled trial of exercise and cognitive function in chronic stroke survivors. They conducted an eight week randomized controlled trial of thrice-weekly progressive resistive stationary bicycle training. In contrast to our findings, they observed no significant between-group differences in executive functions, as measured by Stroop Test and Trail Making Tests, at trial completion. Differences in both the duration (i.e., eight versus six months) and type of training (i.e., aerobic versus mulitmodal exercise training) are probable contributing factors. It is noteworthy that Colcombe and Kramer (6) reported that the effect size of multimodal exercise training was larger than aerobic training (0.41 versus 0.59).

Our recreation and leisure activities may have also promoted executive functions among the INT participants. To reiterate, we purposively included group activities that emphasized planning, strategy, decision making, and learning. Complex patterns of mental activity in early, mid-life, and late-life stages is associated with a significant reduction in dementia incidence (15). Critically, increased complex mental activity in late life was associated with lower dementia rates independent of other predictors; a dose-response relationship was also evident between extent of complex mental activities in late life and dementia risk. Furthermore, cohort studies have highlighted the benefit of socialization in reducing dementia risk (16,38). Recent randomized controlled trials also show that activities such as computer lessons (39) and playing a real-time strategy video game (40) provide cognitive benefits for older adults.

We also demonstrated that improved selective attention and conflict resolution was associated with greater functional capacity. This concurs with and extends our previous observation that Stroop Test performance was significantly associated with 6MWT performance in chronic stroke survivors (4).

We acknowledge the limitations of our study. In terms of lesion site, size, and stroke type, our study cohort of chronic stroke survivors is a heterogeneous sample and this may have limited our ability to detect between-group differences. Thus, we may be providing conservative estimates of efficacy of exercise training and recreational activities on executive cognitive performance in chronic stroke survivors. Second, our study sample of older adults with mild chronic stroke limits the generalizability of our results to those with more severe stroke-related impairments. Third, the small number of participants in this proof-of-concept study increased the possibility of Type II error (20) and imbalance in baseline characteristics (e.g. cognitive function, sex, and functional ability). Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm our current findings and to extend our understanding of the role of exercise training and recreational activities in promoting executive functions in stroke survivors.

In conclusion, our proof-of-concept study suggests that a six-month program of exercise and recreation is a promising strategy for promoting executive functions in older adults with mild chronic stroke. Thus, clinicians should consider prescribing exercise and recreational activities in the cognitive rehabilitation of chronic stroke survivors (41).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following people for their assistance in facilitating the classes or study protocol: Chihya Hung, Amira Tawashy, Dominik Zbogar, Alvin Ip, Silvia Hua, Jennifer Lee, Jacqulyne Cragg, Debbie Rand, Kristen Kokotilo, and Janet Soucy. We also acknowledge Drs. Nancy Mayo and Mark Bayley for their project leadership.

Funding: The Canadian Stroke Network provided funding for this study. TLA is a Canada Research Chair Tier II in Physical Activity, Mobility, and Cognitive Neuroscience and was supported by a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award, a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award, and a Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada’s Henry JM Barnett’s Scholarship. Further support for this study was provided to J.J.E. in a career scientist award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MSH 63617)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Sponsor’s Role: None.

Author Contributions: TLA and JJE: Study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript, and critical review of manuscript.

All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Erkinjuntti T, Bowler JV, DeCarli CS, et al. Imaging of static brain lesions in vascular dementia: Implications for clinical trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13 (Suppl 3):S81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kokmen E, Whisnant JP, O’Fallon WM, Chu CP, Beard CM. Dementia after ischemic stroke: A population-based study in rochester, minnesota (1960–1984) Neurology. 1996;46:154–159. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker-Collo S, Feigin V. The impact of neuropsychological deficits on functional stroke outcomes. Neuropsychol Rev. 2006;16:53–64. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu-Ambrose T, Pang MY, Eng JJ. Executive function is independently associated with performances of balance and mobility in community-dwelling older adults after mild stroke: Implications for falls prevention. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23:203–210. doi: 10.1159/000097642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lesniak M, Bak T, Czepiel W, Seniow J, Czlonkowska A. Frequency and prognostic value of cognitive disorders in stroke patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26:356–363. doi: 10.1159/000162262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colcombe S, Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: A meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:125–130. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu-Ambrose T, Nagamatsu LS, Graf P, Beattie BL, Ashe MC, Handy TC. Resistance training and executive functions: A 12-month randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:170–178. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu-Ambrose T, Donaldson MG, Ahamed Y, et al. Otago home-based strength and balance retraining improves executive functioning in older fallers: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1821–1830. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cumming TB, Tyedin K, Churilov L, Morris ME, Bernhardt J. The effect of physical activity on cognitive function after stroke: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics. 2011;14:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonnell MN, Smith AE, Mackintosh SF. Aerobic exercise to improve cognitive function in adults with neurological disorders: A systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:1044–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pang MYC, Charlesworth SA, Lau RWK, Chung RCK. Using aerobic exercise to improve health outcomes and quality of life in stroke: Evidence-based exercise prescription recommendations. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2013;35:7–22. doi: 10.1159/000346075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballard C, Rowan E, Stephens S, Kalaria R, Kenny RA. Prospective follow-up study between 3 and 15 months after stroke: Improvements and decline in cognitive function among dementia-free stroke survivors >75 years of age. Stroke. 2003;34:2440–2444. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000089923.29724.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quaney BM, Boyd LA, McDowd JM, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognition and motor function poststroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23:879–885. doi: 10.1177/1545968309338193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansson BB, Belichenko PV. Neuronal plasticity and dendritic spines: Effect of environmental enrichment on intact and postischemic rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:89–96. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200201000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valenzuela MJ, Sachdev P. Brain reserve and dementia: A systematic review. Psychol Med. 2006;36:441–454. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fratiglioni L, Wang HX, Ericsson K, Maytan M, Winblad B. Influence of social network on occurrence of dementia: A community-based longitudinal study. Lancet. 2000;355:1315–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rand D, Eng JJ, Liu-Ambrose T, Tawashy AE. Feasibility of a 6-month exercise and recreation program to improve executive functioning and memory in individuals with chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24:722–729. doi: 10.1177/1545968310368684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kluding PM, Tseng BY, Billinger SA. Exercise and executive function in individuals with chronic stroke: A pilot study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2011;35:11–17. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e318208ee6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marzolini S, Oh P, McIlroy W, Brooks D. The effects of an aerobic and resistance exercise training program on cognition following stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1545968312465192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: Applications to practice. Norwalk: Appleton and Lange; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The montreal cognitive assessment, moca: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graf P, Uttl B, Tuokko H. Color- and picture-word stroop tests: Performance changes in old age. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1995;17:390–415. doi: 10.1080/01688639508405132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spreen O, Strauss E. A compendium of neurological tests. 2. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baddeley A. Working memory. Science. 1992;255:556–559. doi: 10.1126/science.1736359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carod-Artal J, Egido JA, Gonzalez JL, Varela de Seijas E. Quality of life among stroke survivors evaluated 1 year after stroke: Experience of a stroke unit. Stroke. 2000;31:2995–3000. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.12.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cinamon JS, Finch L, Miller S, Higgins J, Mayo N. Preliminary evidence for the development of a stroke specific geriatric depression scale. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:188–198. doi: 10.1002/gps.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enright PL, McBurnie MA, Bittner V, et al. The 6-min walk test: A quick measure of functional status in elderly adults. Chest. 2003;123:387–398. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fulk GD, Echternach JL. Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change of gait speed in individuals undergoing rehabilitation after stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2008;32:8–13. doi: 10.1097/NPT0b013e31816593c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berg K, Wood-Dauphinee S, Gayton D. Measuring balance in the elderly: Preliminary development of an instrument. Physiotherapy Canada. 1989;41:304–310. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blum L, Korner-Bitensky N. Usefulness of the berg balance scale in stroke rehabilitation: A systematic review. PHYS THER. 2008;88:559–566. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pang MY, Eng JJ, Dawson AS, McKay HA, Harris JE. A community-based fitness and mobility exercise program for older adults with chronic stroke: A randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1667–1674. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ICH Expert Working Group. Ich harmonised tripartite guideline: Statistical principals in clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine. 1999;18:1905–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegle S. Nonparametric statistics for the behavioural sciences. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, Maki B. Measuring balance in the elderly: Validation of an instrument. Can J Public Health. 1992;83 (Suppl 2):S7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colcombe SJ, Kramer AF, Erickson KI, et al. Cardiovascular fitness, cortical plasticity, and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3316–3321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400266101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagamatsu LS, Handy TC, Hsu CL, Voss M, Liu-Ambrose T. Resistance training promotes cognitive and functional brain plasticity in seniors with probable mild cognitive impairment. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:666–668. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helmer C, Damon D, Letenneur L, et al. Marital status and risk of alzheimer’s disease: A french population-based cohort study. Neurology. 1999;53:1953–1958. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klusmann V, Evers A, Schwarzer R, et al. Complex mental and physical activity in older women and cognitive performance: A 6-month randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:680–688. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basak C, Boot WR, Voss MW, Kramer AF. Can training in a real-time strategy video game attenuate cognitive decline in older adults? Psychol Aging. 2008;23:765–777. doi: 10.1037/a0013494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt W, Endres M, Dimeo F, Jungehulsing GJ. Train the vessel, gain the brain: Physical activity and vessel function and the impact on stroke prevention and outcome in cerebrovascular disease. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2013;35:303–312. doi: 10.1159/000347061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]