SUMMARY

The developing limb is a useful model for studying organogenesis and developmental processes. Although Cre alleles exist for conditional loss- or gain-of-function in limbs, Cre alleles targeting specific limb subdomains are desirable. Here we report on the generation of the Hoxa13:Cre line, in which the Cre gene is inserted in the endogenous Hoxa13 gene. We provide evidence that the Cre is active in embryonic tissues/ regions where the endogenous Hoxa13 gene is expressed. Our results show that cells expressing Hoxa13 in developing limb buds contribute to the entire autopod (hand/feet) skeleton and validate Hoxa13 as a distal limb marker as far as the skeleton is concerned. In contrast, in the limb musculature, Cre-based fate mapping shows that almost all muscle masses of the zeugopod (forearm) and part of the triceps contain Hoxa13-expressing cells and/or their descendants. Besides the limb, the activity of the Cre is detectable in the urogenital system and the hindgut, primarily in the epithelium and smooth muscles. Together our data show that the Hoxa13:Cre allele is a useful tool for conditional gene manipulation in the urogenital system, posterior digestive tract, autopod and part of the limb musculature.

Keywords: genetics, process, mammal, organism, organogenesis, process, fate specification, process, limb/wing/appendage, tissue, muscle, tissue, skeletal, tissue, reproductive, tissue, gut, tissue

INTRODUCTION

The Hox family of transcription factors plays a key role in the establishment of the body architecture (Iimura and Pourquie, 2007; Kmita and Duboule, 2003; Krumlauf, 1994; Young and Deschamps, 2009). In the course of evolution, Hox genes have been repetitively recruited to achieve novel functions, as illustrated with their role in vertebrate limb morphogenesis (Zakany and Duboule, 2007). In mammals, there are 39 Hox genes organized in four clusters, referred to as HoxA, B, C, and D. Each Hox cluster contains a series of 9 to 11 contiguous genes transcribed from the same DNA strand, thus defining a 5′ to 3′ polarity to the cluster. Hoxa13 is the most 5′ member of the HoxA cluster. In the mouse, its expression is first detected at embryonic day 7.5 (E7.5) in the allantois (Scotti and Kmita, 2012; Shaut et al., 2008), an epiblast derivative located in the exocoelom. At E9.5, Hoxa13 mRNA is observed in the tail bud, and by E10 in the distal posterior region of the developing forelimb bud mesenchyme (Haack and Gruss, 1993). A similar expression pattern is detected in the hindlimb by E11. Subsequently, Hoxa13 expression domain in the limb encompasses the mesenchyme of the entire presumptive autopod (hand/foot) and by E14, it becomes restricted to peridigital tissue and interarticular condensations of digits (Stadler et al., 2001). A fainter Hoxa13 expression is also found in the zeugopod (forearm) and stylopod (arm), in a domain corresponding to the developing musculature (Yamamoto and Kuroiwa, 2003). Finally, Hoxa13 is expressed in the genital bud starting from E11.5, and at E14 in the urogenital system and gastrointestinal tract (Warot et al., 1997).

In mouse, Hoxa13 loss of function is embryonic lethal at mid-gestation due to impaired development of the vasculature within the placental labyrinth (Fromental-Ramain et al., 1996; Scotti and Kmita, 2012; Shaut et al., 2008). Mutant embryos also display a severely defective urogenital system, characterized by hypoplasia of the urogenital sinus and abnormal localization of ureters extremities (Warot et al., 1997). In the limb, inactivation of Hoxa13 causes defects in the autopod, including the lack of digit 1, shortening and malformation of the other digits and fusion of the interdigital tissue (Fromental-Ramain et al., 1996; Perez et al., 2010). The autopod phenotype of Hoxa13−/− mutants is, at least in part, due to cell adhesion defects in cartilage condensations and reduced apoptosis in the interdigital tissue (Knosp et al., 2004; Salsi and Zappavigna, 2006; Stadler et al., 2001). Hoxa13−/− mutants have also defects in the placenta and this phenotype is associated with Hoxa13 expression in the allantois (Scotti and Kmita, 2012), which contains precursor cells of the fetal vasculature of the placenta. Such delay between gene expression and its functional outcome prompted us to identify all tissues and organs originating from Hoxa13-expressing cells. To this end, we took advantage of the loxP-Cre system to perform fate-mapping experiments and generated a novel Cre allele, in which the Cre gene is inserted at the Hoxa13 start codon. Here, we describe the generation of the Hoxa13:Cre allele and report on the fate of Hoxa13 expressing cells. These data also reveal the tissues/organs in which the Hoxa13:Cre allele can be used as a tool for conditional gain- and loss-of-function.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

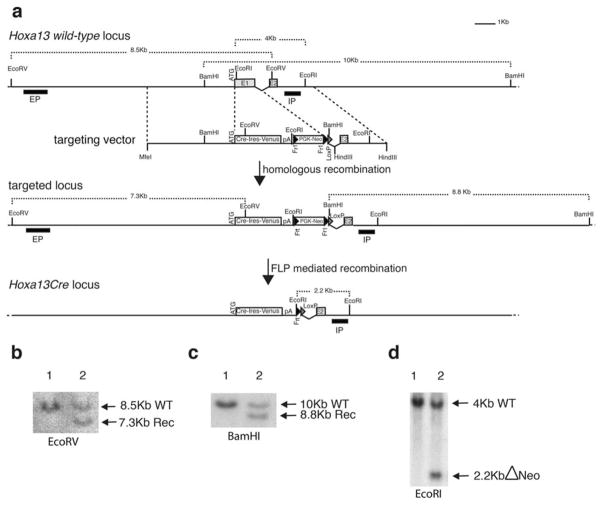

To genetically label Hoxa13-expressing cells and their descendants, we targeted a Cre:Ires:Venus cassette into the Hoxa13 start codon via homologous recombination in ES cells (Fig. 1a). Successful targeting was confirmed F1 by restriction fragment length polymorphism detectable using a probe external to the targeting vector while the absence of additional random insertion was verified using an internal probe (Fig. 1b,c). Two targeted clones were injected into mouse blastocysts to generate chimeras. Following germline transmission of the Hoxa13:Creneo+ allele, the neomycin selection cassette was eliminated in vivo by crossing Hoxa13:Creneo+/+ mice with FLPeR partners (Farley et al., 2000) (Fig. 1d). Hoxa13:Creneo−/+ animals (Hoxa13:Cre/+ hereafter) are fully viable and fertile but Hoxa13:Cre homozygous mutants die at mid-gestation of placental defects, consistent with the lethality of other Hoxa13-null mutant previously reported (Fromental-Ramain et al., 1996; Shaut et al., 2008; Stadler et al., 2001). While an IRES-Venus cassette was inserted downstream of the Cre coding sequence to directly monitor Hoxa13-Cre expression, we were unable to detect any fluorescence from the IRES-Venus cassette. We therefore focused our analyses on the expression of the Cre-reporter transgenes.

FIG. 1.

Generation of the Hoxa13:Cre mouse line. (a) Targeting of the endogenous Hoxa13 locus. (Top) Wild-type Hoxa13 locus. The targeting vector is shown below and dotted lines indicate the position of the homologous arms. (Middle) Scheme of the targeted locus after homologous recombination in ES cells. The position of the internal (IP) and external probes (EP) and restriction sites used for Southern analysis are indicated. (Bottom) The targeted locus after FLP-mediated deletion of the PGK-Neo selection cassette. (b) Southern blots of ES clones using the external probe and (c) the internal probe to detect the targeted allele (lane 2). (d) Southern blot analysis of wild type (lane 1) and heterozygous (lane 2) mice after in vivo FLP-mediated deletion.

We first compared the Cre-reporter expression with Hoxa13 expression pattern at various stages of development. For whole-mount Cre-reporter expression, we used the Rosa26R reporter mice (Soriano, 1999). In Hoxa13:Cre/+;Rosa26R/+ embryos, a transcriptional stop cassette is excised in presence of the Cre recombinase, irreversibly activating the β-gal reporter expression in all Hoxa13 expressing cells and their descendants (hereafter referred to as Hoxa13lin+ cells). As previously reported, Hoxa13 expression in the developing forelimb initiates at E10.0 in the distal bud (Fig. 2a, arrowhead). In contrast, X-gal staining starts to be detectable in the forelimb bud at E10.75 (Fig. 2b,e), consistent with the delay existing between the transcriptional activation of the Cre gene and the synthesis of the β-gal reporter protein (Scotti and Kmita, 2012). X-gal staining is also observed in the tail bud (Fig. 2b–c,e–f) consistent with Hoxa13 expression (Fig. 2a,d), which is first observed in this tissue at E9.0 (not shown). Subsequently, X-gal positive cells are located in the posterior mesoderm and neural tube, with a rostral limit being more posterior in the mesoderm (Fig. 2f,i,l). Hoxa13lin+ cells are also detected in the umbilical cord and developing genitals (Fig. 2c,f,l), reminiscent of Hoxa13 expression in these structures (Warot et al., 1997).

FIG. 2.

Comparison between Hoxa13 expression and the localization of Hoxa13lin+ cells in the developing embryo. (a, d, g, j, m, p) Whole-mount in situ hybridization of wild-type embryos with the Hoxa13 RNA probe. (b, c, e, f, h, i, k, l, n, o) Whole-mount X-gal staining of Hoxa13:Cre/+; Rosa26R/+ embryos. Black arrowhead in (a) indicates Hoxa13 expression domain in the developing limb bud. Dotted lines in (b) demarcate the forelimb bud. (o) X-gal staining of the gastro-intestinal track. TB: tail bud; UC: umbilical cord; US: urogenital sinus; NT: neural tube; s: stomach; ce: caecum; co: colon; re: rectum.

In order to get a more precise characterization of the fate of Hoxa13-expressing cells, in particular within internal organs, we generated Hoxa13:Cre; mT-mG embryos to analyze the Cre-reporter expression on sections. The Cre reporter mT-mG produces red fluorescence in cells in which the Cre has never been expressed and green fluorescence after Cre-mediated recombination (Muzumdar et al., 2007). In the urogenital system, Hoxa13lin+ cells are found posterior to the kidneys (Fig. 3a–e) in the developing ureters (Fig. 3a–j), bladder (Fig. 3p–t), urethra (Fig. 3u–y). Interestingly, Hoxa13lin+ cells are found only in the smooth muscle compartment in the ureters (Fig. 3k–o) and uterus (Fig. 3u–y) while they are also present in the epithelium of the bladder and urethra (Fig. 3p–y). Hoxa13lin+ cells are also observed in the gastro-intestinal tract, posterior to the caecum (Fig. 2o), although few scattered Hoxa13lin+ cells are detectable in the caecum (Supporting Information Fig. 1). Reminiscent of the fate-map in the bladder and urethra, Hoxa13lin+ cells are found in the epithelium lining the lumen of the developing colon (Fig. 4a,b,f,g). Co-immunostaining for GFP and smooth muscle actin also reveals that in the developing hindgut, Hoxa13lin+ cells are located in the smooth muscle layers but not in the enteric plexus (Fig. 4b–e, g–j and Supporting Information Fig. 2).

FIG. 3.

Contribution of Hoxa13lin+ cells to the urogenital system. (a–y) Co-immunostaining for GFP and alpha smooth muscle actin (SMA) on cryosections of E18.5 Hoxa13Cre/+; mT/mG fetuses. (a–e) Frontal section showing the presence Hoxa13lin+ cells in ureter but not to the adrenal (suprarenal) gland (ag) nor kidney (K). (f–j) Higher magnification of the proximal region of the ureter. Note the absence of Hoxa13lin+ cells in the kidney-ureter junction. (k–o) Transverse section through the ureter. (p–t) Frontal sections of the bladder. Nuclei are stained with DAPI in panels a, f, k, p, u. mT (red fluorescence) is shown as a control of GFP-negative cells. ad: adventitia; ag: adrenal gland; ct: connective tissue; ilm: inner longitudinal muscular layer; k: kidney; lu: lumen; ocm: outer circular muscular layer; sm: smooth muscle; u: ureter; ur: urethra; uro: urothelium; ut: uterus; vc: vesicular cavity.

FIG. 4.

Fate map of Hoxa13-expressing cells in the developing hindgut. (a–j) Transverse section of E18.5 developing colon isolated from Hoxa13Cre/+; mT-mG/+ embryos. (f–j) High magnification of the dotted square in panels a–e. Hoxa13lin+ cells (green, mG-expressing cells) are present in the serosa (se), longitudinal fibers (lf), and circular fibers (cf) (muscular coat), mucous coat (mc) and the epithelium lining the lumen (ep). en: enteric plexus.

As far as the developing limb is concerned, Hoxa13lin+ cells are initially located in the distal limb bud (Fig. 2e), similar to Hoxa13 expression (Fig. 2d). Analysis of longitudinal sections of E10.5 limb buds shows that Hoxa13lin+ cells are in the mesenchyme of the distal limb, but not in the ectoderm nor in blood vessels (Supporting Information Fig. 2a). From E11.5 to 2 E12.5, Hoxa13lin+ cells are primarily found in the presumptive autopod although few Hoxa13lin+ cells are also observed in more proximal regions of the developing limb (Fig. 2h–k and Supporting Information Fig. 3b). From E12.5 onwards, the β-gal expression pattern in the proximal domain suggests that Hoxa13lin+ cells are located in the developing limb musculature, primarily in the zeugopod muscles and part of the developing triceps (Fig. 5a). Although Hoxa13 expression in the proximal limb domain is barely detectable by whole-mount in situ hybridization, previous analysis on sections revealed expression in the developing muscles of the zeugopod and stylopod in both mice and chick (Dolle and Duboule, 1989; Haack and Gruss, 1993; Perez et al., 2010; Yamamoto et al., 1998; Yamamoto and Kuroiwa, 2003). Limb muscles consist of two different components: muscle cells derived from Pax3-expressing myogenic progenitors that delaminate from the hypaxial dermomyotome and migrate in the limb bud and connective tissue originating from the limb mesenchyme (reviewed in e.g. (Murphy and Kardon, 2011)). The latter eventually gives rise to tendons and three layers of connective tissue that surround the muscular mass (Hasson, 2011). We thus performed immunostaining for Pax3 on sagittal cryosections of Hoxa13:Cre/+;mT-mG forelimbs to establish the identity of Hoxa13lin+ cells in the forming muscles. At 47-somite stage (E11.5), few isolated GFP+ cells are located in the proximal limb bud (Supporting Information Fig. 4a). Co-immunostaining for Pax3 and GFP suggests that these Hoxa13lin+ cells are most likely myoblasts (Supporting Information Fig. 4b,c, dotted box and arrowhead). By 53-somite stage (E12.5), there is a significant increase of GFP+ cells in the dorsal pre-muscular mass (Supporting Information Fig. 4d–f and dotted boxes). To further test for the identity of the proximal Hoxa13lin+ cells, we performed co-immunostaining for the Myosin Heavy Chain (my-32) and GFP on sections of E14.5 Hoxa13:Cre/+;mT-mG forelimbs. Analysis of both dorsal and ventral muscle masses of the zeugopod shows that a large proportion of GFP+ cells also express my-32, thereby indicating that Hoxa13lin+ cells contribute to the myogenic lineage (Figs. 5 and 6). Yet, we also found few Hoxa13lin+ cells that do not express my-32 (Fig. 5b–g, arrows), raising the possibility that Hoxa13lin+ cells also contribute to the connective tissue. We thus performed co-immunostaining for GFP and Tcf4, a marker for connective tissue, and found that the vast majority of Hoxa13lin+ cells do not express Tcf4 (Fig. 5h–m). Only few scattered Hoxa13lin+ cells seem to also express Tcf4 (Fig. 5k–m, white arrows). Together these data indicate that the proximal Hoxa13lin+ cells are primarily part of the myogenic lineage. This result reveals a major difference between Hoxa13 and its neighboring gene Hoxa11, which expression in limb muscle masses was recently shown to be restricted to the connective tissue (Swinehart et al., 2013) Co-immunostaining for my-32 and GFP confirms that Hoxa13lin+ cells are present in almost all muscle masses of zeugopod (Fig. 6) while in the stylopod, they are present primarily in the triceps brachii lateralis (#18 in Fig. 6p–r,g–i). Because the localization of Hoxa13lin+ cells is bias toward distal muscles, the contribution of Hoxa13lin+ cells to the myogenic lineage may be the consequence of a mechanism that takes place after muscle progenitors have entered the limb bud, which could be triggered by (unknown) signaling emanating from the distal limb bud.

FIG. 5.

Cre reporter expression in the developing forelimb muscles. (a) Whole-mount X-gal staining of Hoxa13:Cre/1;Rosa26R/1 forelimb buds from e12.5 to postnatal day 2 (P2). The Cre reporter expression is observed in the entire autopod as well as in more proximal regions of the developing limb, where its expression suggests expression in the developing limb musculature and/or associated connective tissue. Scale bars5100 mm. (b–g) Co-immunostaining for GFP and fast skeletal Myosin on transverse section of the Hoxa13:Cre/1; mT-mG/1 zeupogod at E14.5. View of the flexor digitorium sublimis (b–d) and extensor digitorium communis (e–g). Note that there are few scattered Hoxa13lin1 cells that do not express fast skeletal Myosin (white arrows). (h–m) Co-immunostaining for GFP and Tcf4. (h–j) View of the extensor digitorium communis and lateralis. (k–m) high magnification of the dotted rectangles in panels h to j. Yellow arrowheads point to example of cells expressing Tcf4 but not GFP (i.e. cells that are not Hoxa13lin+ cells). White arrowheads point to the few Hoxa13lin+ cells that express Tcf4, though at lower level compared with the other Tcf4-expressing cells. (n–p) Transverse section of Hoxa13:Cre/+; mT-mG/ + zeupogod at E14.5 showing the overall distribution of Hoxa13lin positive cells (mG-expressing cells in green) and Hoxa13lin negative cells (mT-expressing cells in red). Note the nonuniform distribution of mG-expressing cells, in particular in the Extensor Carpi Ulnaris (dotted rectangle), suggesting a clonal contribution of Hoxa13lin+ cells to the various muscles.

FIG. 6.

Differential contribution of Hoxa13lin+ cells to the limb muscles. Expression pattern of GFP and fast skeletal Myosin (my-32) on transverse sections of Hoxa13:Cre/+; mT-mG/+ forelimb bud at E14.5 (a–i) and E18.5 (j–r). Transverse sections through the distal (a–c; j–l) and proximal part (d–f; m–o) of the zeugopod and through the stylopod (g–i; p–r). For muscle nomenclature, see Table 1. R: radius; U: ulna; H: humerus; dor: dorsal; ven: ventral; ant: anterior; post: posterior.

Hoxa13 is widely used as an autopod marker based on its expression pattern. To establish the contribution of Hoxa13lin+ cells to the limb skeletal elements we examined sagittal sections of Hoxa13:Cre/+; mT-mG/ + limbs. At E14.5, the entire autopod is formed of Hoxa13lin+ cells (Fig. 7a–c) except the ectoderm and capillaries (mT+ cells in Supporting Information Fig. 6). As far as the skeleton is concerned, the wrist appears to be the boundary between Hoxa13lin+ and Hoxa13lin- cells. To define more precisely this limit, we analyze E18.5 limbs, which confirmed that the entire skeleton of the autopod is composed of Hoxa13lin+ cells (Fig. 7d–f) with the exception of few cells in the most proximal carpal elements (Fig. 7g–i, GFP-negative, mT-positive cells in the ulnare). In contrast, no Hoxa13lin+ cell was detected in the radius, and only few Hoxa13lin+ cells are found in the ulnar head (Fig. 7g–i). These results confirm the previous assumption that the autopod skeleton originates from Hoxa13-expressing cells. Thus, as far as skeletal elements are concerned, Hoxa13 can be considered as a bona fide marker of autopod progenitors. Nonetheless, from E11.5 onwards, the contribution of Hoxa13-expressing cells to more proximal muscles should be taken into account when using Hoxa13 to mark or verify the presence of cells committed to an “autopod” fate.

FIG. 7.

Hoxa13-expressing cells give rise to all bones of the autopod and mark the boundary between the wrist and the zeugopod. (a–c) Sagittal section through a E14.5 Hoxa13:Cre/+;mT-mG/+ forelimb showing the overall distribution of Hoxa13lin positive cells (mG-expressing cells; green) and Hoxa13lin negative cells (mT-expressing cells; red). Distal is on the left and anterior is up. (d–f) Sagittal section at the autopod-zeugopod boundary of E18.5 Hoxa13:Cre/+;mT-mG/+ forelimb. Hoxa13lin+ cells are visualized by direct detection of GFP fluorescence from the Cre reported allele (green) and immunostaining for my-32 (red) marks muscles. Note that all carpal bones are GFP+ and only few GFP+ cells are present in the ulna head (U). (g–i) high magnification of the ulna head (U) and ulnare (ul) showing few Hoxa13lin negative cells in the ulnare (mT-expressing cells; red) while a small cluster of Hoxa13lin+ cells (green) are present in the ulna head (U). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). R: radius; U: ulna; ra: radiale; i: intermedium; ul: ulnare.

In summary, our study establishes the fate of Hoxa13-expressing cells in the developing embryo and identifies the tissues/organs in which conditional gene loss- or gain-of-function can be achieved with the Hoxa13-Cre allele, i.e. the autopod, the hindgut, the urogenital system posterior to the kidneys and part of the limb musculature.

METHODS

Generation of the Hoxa13:Cre Mice

To generate the targeting vector, a 5.2 kb MfeI-HindIII DNA fragment containing Hoxa13 exon 1 and a 2.5 kb HindIII DNA fragment containing the exon 2 were ligated and inserted into a modified pBluescript SK+ vector. A Cre:Ires:Venus cassette (modified from the Venus/PCS2 vector obtained from Atsushi Miyawaki) was inserted at the Hoxa13 ATG using the Recombineering technique (Copeland et al., 2001) and replaces the entire exon 1. The SV40 666bp sequence and neomycin cassette flanked by two Frt sites and a loxP site (from the PL451 plasmid obtained from N. Copeland, NCI Frederick) were added to the 3′ end of the Cre:Ir-es:Venus cassette. The vector backbone was eliminated by PacI digest prior electroporation into R1 ES cells. Following selection with G418, approximately 400 individual ES cell clones were analyzed by Southern blot for homologous recombination. Two independent clones were injected into blastocysts obtained from C57BL/6J mice, subsequently implanted into pseudo-pregnant females. Germline transmission of the Hoxa13:Cre allele was obtained for both clones and the F1 offspring were intercrossed with homozygous FLPeR mice (Farley et al., 2000) to delete the neomycin cassette. The Hoxa13:Cre mouse line will be publically available upon acceptance of the manuscript. All animal experiments described in this article were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal (protocol #2010-03).

Genotyping and Mating Schemes

Genotyping of ES cells, tail biopsies and yolk sacs was performed by Southern blot analysis. A scheme with restriction sites and probes used for ES cell genotyping is presented in Figure 1. Hoxa13:Cre mice were genotyped using the internal probe described in Figure 1 and EcoRI digest. The Cre recombinase reporter lines were genotyped by PCR as previously described: Rosa26R ((Soriano, 1999) and mT/mG (Muzumdar et al., 2007). For fate mapping, we crossed Hoxa13:-Cre/+ males with Rosa26R or mT/mG homozygous females and used double heterozygous embryos and newborns.

Whole Mount In Situ Hybridization, X-Gal Staining, and Imaging

Whole mount in situ hybridizations were performed using previously described protocol (Kondo et al., 1998) and probe (Warot et al., 1997). Whole mount X-gal staining was performed using standard protocols (Zakany et al., 1988). After staining, embryos and newborn specimens were washed three times for 1 h in PBS and stored in 4% PFA at 4°C. All specimens were imaged using the Leica DFC320 camera. X-gal staining was performed on a minimum of five samples per stage.

Immunostaining

Whole embryos and limbs were dissected in ice cold PBS and fixed 1 to 2 h in 4% PFA on ice, rinsed three times 10 min in PBS an then placed in 30% sucrose in PBS overnight. Specimens were then embedded in a 1:1 mix of 30% sucrose in PBS and Cryomatrix (Thermo Shandon). Immunostaining for my-32 (1:750, Sigma) was performed using the M.O.M kit (Vector) as in (Warot et al., 1997). Immunostaining with anti Pax3 (1:250, concentrate, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) was performed on 12 μm cryosections as previously described (Relaix et al., 2003). Primary and Secondary antibodies used in this work are presented in Supporting Information Table 2. All images were captured using a ZEISS LSM710 confocal microscope. At least three samples per stage and 10 sections per sample were analyzed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: Canadian Institute for Health Research, Contract grant number: MOP-126110; Contract grant sponsors: Canada Research Chair program (to M.K.) and Molecular Biology Program of the University of Montréal (to M.S. and Y.K.).

The authors are particularly grateful to Qinzhang Zhu from the IRCM transgenic core facility for the ES cell work and production of chimeras. The authors thank Annie Dumouchel for technical help and Drs. Artur Kania and Maëva Luxey for critical reading of the manuscript as well as lab members for insightful discussions and sharing reagents.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

LITERATURE CITED

- Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Court DL. Recombineering: A powerful new tool for mouse functional genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:769–779. doi: 10.1038/35093556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolle P, Duboule D. Two gene members of the murine HOX-5 complex show regional and cell-type specific expression in developing limbs and gonads. EMBO J. 1989;8:1507–1515. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley FW, Soriano P, Steffen LS, Dymecki SM. Widespread recombinase expression using FLPeR (flipper) mice. Genesis. 2000;28:106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromental-Ramain C, Warot X, Messadecq N, LeMeur M, Dolle P, Chambon P. Hoxa-13 and Hoxd-13 play a crucial role in the patterning of the limb auto-pod. Development. 1996;122:2997–3011. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haack H, Gruss P. The establishment of murine Hox-1 expression domains during patterning of the limb. Dev Biol. 1993;157:410–422. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson P. "Soft" tissue patterning: Muscles and tendons of the limb take their form. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:1100–1107. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iimura T, Pourquie O. Hox genes in time and space during vertebrate body formation. Dev Growth Differ. 2007;49:265–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2007.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kmita M, Duboule D. Organizing axes in time and space; 25 years of colinear tinkering. Science. 2003;301:331–333. doi: 10.1126/science.1085753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knosp WM, Scott V, Bachinger HP, Stadler HS. HOXA13 regulates the expression of bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 7 to control distal limb morphogenesis. Development. 2004;131:4581–4592. doi: 10.1242/dev.01327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Zakany J, Duboule D. Control of colinearity in AbdB genes of the mouse HoxD complex. Mol Cell. 1998;1:289–300. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumlauf R. Hox genes in vertebrate development. Cell. 1994;78:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M, Kardon G. Origin of vertebrate limb muscle: The role of progenitor and myoblast populations. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2011;96:1–32. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385940-2.00001-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez WD, Weller CR, Shou S, Stadler HS. Survival of Hoxa13 homozygous mutants reveals a novel role in digit patterning and appendicular skeletal development. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:446–457. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Polimeni M, Rocancourt D, Ponzetto C, Schafer BW, Buckingham M. The transcriptional activator PAX3-FKHR rescues the defects of Pax3 mutant mice but induces a myogenic gain-of-function phenotype with ligand-independent activation of Met signaling in vivo. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2950–2965. doi: 10.1101/gad.281203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsi V, Zappavigna V. Hoxd13 and Hoxa13 directly control the expression of the EphA7 Ephrin tyrosine kinase receptor in developing limbs. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1992–1999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotti M, Kmita M. Recruitment of 5′ Hoxa genes in the allantois is essential for proper extra-embryonic function in placental mammals. Development. 2012;139:731–739. doi: 10.1242/dev.075408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaut CA, Keene DR, Sorensen LK, Li DY, Stadler HS. HOXA13 Is essential for placental vascular patterning and labyrinth endothelial specification. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler HS, Higgins KM, Capecchi MR. Loss of Eph-receptor expression correlates with loss of cell adhesion and chondrogenic capacity in Hoxa13 mutant limbs. Development. 2001;128:4177–4188. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.21.4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warot X, Fromental-Ramain C, Fraulob V, Chambon P, Dolle P. Gene dosage-dependent effects of the Hoxa-13 and Hoxd-13 mutations on morphogenesis of the terminal parts of the digestive and urogenital tracts. Development. 1997;124:4781–4791. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Gotoh Y, Tamura K, Tanaka M, Kawakami A, Ide H, Kuroiwa A. Coordinated expression of Hoxa-11 and Hoxa-13 during limb muscle patterning. Development. 1998;125:1325–1335. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.7.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Kuroiwa A. Hoxa-11 and Hoxa-13 are involved in repression of MyoD during limb muscle development. Dev Growth Differ. 2003;45:485–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169x.2003.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T, Deschamps J. Hox, Cdx, and anteroposterior patterning in the mouse embryo. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2009;88:235–255. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(09)88008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakany J, Duboule D. The role of Hox genes during vertebrate limb development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakany J, Tuggle CK, Patel MD, Nguyen-Huu MC. Spatial regulation of homeobox gene fusions in the embryonic central nervous system of transgenic mice. Neuron. 1988;1:679–691. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.