Abstract

Significance: Methods employed for preventing and eliminating biofilms are limited in their efficacy on mature biofilms. Despite this a number of antibiofilm formulations and technologies incorporating ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) have demonstrated efficacy on in vitro biofilms. The aim of this article is to critically review EDTA, in particular tetrasodium EDTA (tEDTA), as a potential antimicrobial and antibiofilm agent, in its own right, for use in skin and wound care. EDTA's synergism with other antimicrobials and surfactants will also be discussed.

Recent Advances: The use of EDTA as a potentiating and sensitizing agent is not a new concept. However, currently the application of EDTA, specifically tEDTA as a stand-alone antimicrobial and antibiofilm agent, and its synergistic combination with other antimicrobials to make a “multi-pronged” approach to biofilm control is being explored.

Critical Issues: As pathogenic biofilms in the wound increase infection risk, tEDTA could be considered as a potential “stand-alone” antimicrobial/antibiofilm agent or in combination with other antimicrobials, for use in both the prevention and treatment of biofilms found within abiotic (the wound dressing) and biotic (wound bed) environments. The ability of EDTA to chelate and potentiate the cell walls of bacteria and destabilize biofilms by sequestering calcium, magnesium, zinc, and iron makes it a suitable agent for use in the management of biofilms.

Future Direction: tEDTA's excellent inherent antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity and proven synergistic and permeating ability results in a very beneficial agent, which could be used for the development of future antibiofilm technologies.

Steven L. Percival, PhD

Scope and Significance

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) is a well known metal-chelating agent, extensively used for the treatment of patients who have been poisoned with heavy metal ions such as mercury and lead. More recently EDTA has been used as a permeating and sensitizing agent for treating biofilm-associated conditions in dentistry, on medical devices, and in veterinary medicine. In the case of veterinary medicine, EDTA is formulated as an EDTA solution that is commercially used to treat biofilm-related infections within the ears of dogs.1 In human medicine EDTA is presently formulated into commercially available wound dressings that are used to modulate matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) and manage wound infections.2 EDTA compositions are also being developed and employed for reducing biofilms in intravascular and urinary catheters and therefore represents an antibiofilm agent, which can significantly help to reduce catheter-related bloodstream infections.3–5 EDTA has been utilized for the control of microorganisms and biofilms often by being combined with other actives, which have included alcohol, antibiotics, citric acid, polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) quaternary ammonium compounds, silver, iodine, surfactants, and other antiseptics.

There is growing evidence that EDTA, specifically tetrasodium EDTA (tEDTA), is an antimicrobial and antibiofilm agent in its own right. Based on the characteristics of EDTA it is the aim of this article to critically review tEDTA as a potential antimicrobial and antibiofilm agent for use in skin and wound care.

Translational Relevance

Infections are a significant problem in many medical and environmental situations. These infections are caused by an array of different microorganisms including bacteria, protozoa, fungi, yeasts, and viruses. The prevention of infections, and reduction or elimination of an infection once it is established is of importance,6 particularly in the area of skin and wound care. Environments that increase a patient's risk to infection include the surfaces of objects (internally and externally), fluids and fluid conduits. In healthcare, infections lead to longer hospital stays for patients and increased hospital costs. Even worse, a large number of patient deaths are attributed to infections.

In wound care specifically wound dressings are routinely used in the management of wounds. However, often overlooked is the fact that the wound dressing itself constitutes a potential major source of infection, a hypothetical phenomenon referred to as the “ping-pong pathogenicity theory.”7 The model suggests that biofilms, which grow on the surface of a wound dressing, will disseminate and slough off into the wound bed. The virulence of these detached biofilms will be high, when compared with that of the individual planktonic microbes found within the wound exudate. Consequently, the microbial load within the wound bed will increase and the tolerance to antimicrobial interventions will be enhanced overall by the preformed biofilm disseminating from the wound dressing and entering the wound bed.

Wound dressings are being extensively used for the delivery of actives and antimicrobials to both prevent and treat wound infections; however, they must also be able to control the biofilm that forms on them, the abiotic biofilm.8,9 As pathogenic biofilms in the wound prolong wound healing and increase its infection risk EDTA should be considered a potential agent, either alone or depending on the clinical requirements in combination with antimicrobials and surfactants, for use in the prevention and management of biofilms within both the abiotic and biotic environment. The effect of EDTA and its ability to chelate and potentiate the cell walls of bacteria and its ability to destabilize a biofilm by sequestering calcium, magnesium, zinc, and iron makes it a suitable agent for use in the prevention and management of biofilms. However, further clinical and in vitro evidence is required to warrant its usage in both acute and chronic wounds.

Clinical Relevance

Microorganisms are found contaminating or colonizing all wounds.10 When a wound is colonized with microorganisms they survive as polymicrobial communities encased within a matrix of extracellular polymeric substance (EPS). This community of microorganisms are attached to each other, often in conjunction with a surface, and form cellular aggregates. These cellular aggregates are referred to as microcolonies. The combination of a community of microorganisms, encased within self-generated EPS and attached onto a surface (liquid or solid) is simply defined as a biofilm.10

Biofilms form within all wounds but presently used practices prevent a true picture of their incidence, prevalence, and pathogenicity.10,11 The properties of the biofilm provide a barrier to phagocytic host cells and antimicrobial agents, in particular antibiotics, which delay wound healing and increase a patient's infection risk. One specific mechanism that a biofilm possesses, in its defensive armory, is the ability to sequester antimicrobials. This sequestration process is made possible by the presence of EPS, which provides the biofilm with an inherent tolerance to antimicrobial interventions. Consequently, the use of antimicrobials alone to prevent and control biofilms is often reported to be unsuccessful in medical conditions and on medical devices. This is due to the fact the antimicrobials in general are specifically designed and developed to kill microorganisms not to “break up” the “house” of the biofilm.

A common treatment in both dentistry and the food/water industry is the use of antibiofilm agents, such as EDTA for controlling biofilms. Such an approach could be considered appropriate for preventing and treating biofilms in wounds and other areas linked to the healthcare environment.12

Background

Free-floating or planktonic microorganisms are generally vulnerable to antimicrobials. However, when microorganisms attach to a surface, the predominant microbial state, they often become recalcitrant to many antimicrobials. As discussed, this is because at any biotic or abiotic surface microorganisms proliferate culminating into the formation of an antimicrobial tolerant biofilm. Biofilm formation is a natural, inherent, and genetically controlled process that occurs in the life cycle of microbes within both the natural and medical environments. The development and complete formation of a biofilm community occurs in several phases forming within a few hours. However, this rate of growth is influenced by environmental surroundings and the physical and chemical composition of the surface.

As microorganisms develop into a biofilm significant upregulation of cellular processes by the microorganisms occurs, which ultimately increases their tolerance to antimicrobials, when compared with planktonic growth. Evidence of biofilm tolerance to antimicrobials and immune responses has been documented in many studies and has also been highlighted within in vivo studies in animal wounds. Many chronic wound infections are the result of biofilm formation by microbes, which contributes to the delayed healing process observed.13–15

Discussion of Findings and Relevant Literature

The ability of the EPS within the biofilm to sequester and degrade therapeutic agents indicates a possible key factor as to why many chronic wounds fail to heal in a timely manner. In very early studies polysaccharides were thought to be the major component of EPS. However, more recently it has been shown that EPS is a heterogeneous matrix of polymers, including polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, glycoproteins, metal ions, and phospholipids.16 The composition of EPS will be determined by the location of the biofilm and its microbiota.

As discussed within biofilms microorganisms are known to exhibit an altered phenotype, with different growth and metabolic rates when compared to planktonic microbes. Further to this the synergistic interaction of microorganisms, which coinhabit within the multispecies biofilms, also adds another obstacle impeding effective treatment. Wound biofilms are not composed of single individual microbes. The synergistic interactions between microbes add complexity to the biofilm's chemical and biological make up, which aid enhanced tolerance to fluctuating pH, temperature, nutrients, antimicrobials, and enhanced virulence when interactions between aerobic and anaerobic species occurs.17 Strategies for disrupting the protective biofilm EPS in wounds would be advantageous because this would allow antimicrobials to penetrate and kill the residing microbes that are otherwise protected by the EPS.

EDTA is a typical antimicrobial and chelating agent that has been previously used to extract the EPS from a variety of bacterium for composition determination.18 EDTA has been used to decrease the cation concentration and so increase EPS water solubility and availability to antimicrobials by reduction in crosslinking of the EPS.19

Uses of EDTA in healthcare

Healthcare areas in which infections and biofilms present a problem, and where the use of EDTA, particularly tEDTA may be useful include medical devices and materials used in connection with the eyes, such as contact lenses, wounds, scleral buckles, suture materials, intraocular lenses, catheters, catheter insertion points, endotracheal tubes, skin, and the like. Certain forms of EDTA have been utilized for treating many of these infections. One example would be the use of tEDTA instead of heparin. In view of its low cost, effectiveness as an anticoagulant, antibiofilm, and antimicrobial activity tEDTA, in particular, has been proposed as a replacement for heparin solutions for the maintenance of intravenous catheters in patients.20

EDTA is presently used intravenously for heart and blood vessel conditions including irregular heartbeat, atherosclerosis, angina, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol. Due to calcium being found in atheromatous plaques, early researchers have hypothesized that EDTA might be effective in treating ischemic heart disease by liberating plaque calcium with subsequent positive changes to the properties of the plaque.21

Use of EDTA as an antiseptic

The effect of EDTA on bacteria was reported 50 years ago.22 Numerous EDTA compositions and combinations provide powerful antiseptic activities and function as antimicrobial agents against bacteria and pathogenic yeast.23 EDTA compositions are highly effective in eliminating existing biofilms, and preventing biofilm formation.24,25

The majority of EDTA based antiseptic solutions generally consist of, at least one EDTA salt in solution with efficacy determined by the pH of the environment being treated. The sodium salts of EDTA commonly used as antiseptics or antibiofilm agents include disodium, trisodium, and tetrasodium salts. However, other EDTA salts, including ammonium, di-ammonium, potassium, di-potassium, cupric disodium, magnesium disodium, ferric sodium, and other combinations have been shown to have antimicrobial and antibiofilm capabilities.25,26 The pH of the disinfecting environment will affect efficacy of EDTA and should be a factor of significance during antibiofilm design. For example, a 5% solution of disodium EDTA has a pH of 4.0–5.5, trisodium EDTA a pH range of 7.0–8.0, and tEDTA 8.50–10 and above as specified in the British Pharmacopoeia. For the use of EDTA at physiological pH there will be a combination of sodium EDTAs that exist, namely disodium and trisodium EDTA, with the trisodium salt of EDTA predominating.

EDTA as a potentiating agent

Walsh et al.27 suggested that the binding of cations by EDTA and subsequent weakening of the microbial cell may be responsible for the potentiation against planktonic Staphylococcus aureus. Sharma et al.28 reported that EDTA enhances the use of a photodynamic agent against S. aureus biofilms, with EDTA reported to act as a sequester of Mg2+ and Ca2+ from the EPS of the biofilm. In a more recent study Yoshizumi et al.29 reported that Ca-EDTA was used to enhance the activity of imipenem on a model sepsis mouse model. The potential of EDTA to enhance antimicrobials30 and photodynamic agents is not a new concept and has been realized for decades with other examples readily available.22,31 Table 1 provides a brief overview of some of the combinations of EDTA with antimicrobial agents commonly researched.

Table 1.

Combination of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid with various antimicrobial agents

| Antimicrobial Agent (in Combination with EDTA) | Planktonic Bacteria | Biofilm Bacteria | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eugenol | Staphylococcus aureus Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

27 | |

| Toluidine | Staphylococcus epidermis | 28 | |

| Imipenem | Escherichia coli | 29 | |

| Polymyxin B sulfate Benzylalkonium chloride Chlorohexidine diacetate |

P. aeruginosa | 22 | |

| Penicillin Oxytetracydine Chloramphenicol |

E. coli | 45 | |

| Benzalkonium chloride Cetylpyridinum Chloroxylenol Tricolsan Chlorohexidine |

P. aeruginosa | 46 |

EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid.

EDTA chemistry

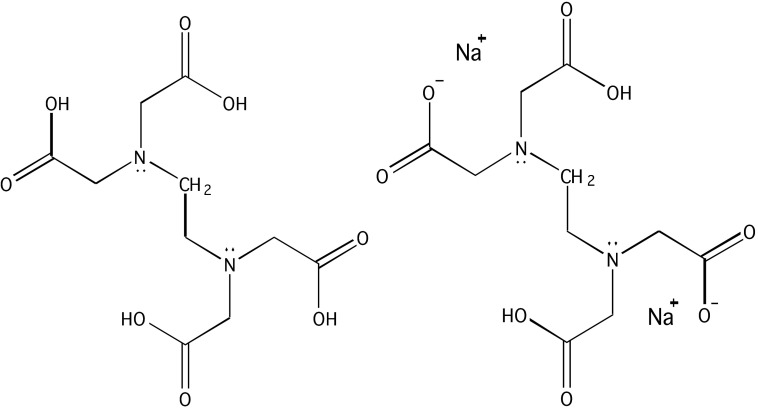

The structure EDTA,4 is the conjugate base that is the ligand, and H4EDTA, is the precursor to that ligand. At very low pH the fully protonated H6EDTA2+ form predominates, whereas at very high pH or very basic conditions, the fully deprotonated EDTA4− form is prevalent.32 EDTA has traditionally been useful as a metal chelator due to its high density of ligands and resulting affinity for metal ions with binding typically occurring through its two amines and four carboxylate groups. Figure 1 shows the conjugate base of EDTA.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of EDTA. Left: Conjugate base of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) fully protonated. Right: disodium EDTA.

Mode of action

The antimicrobial effects of EDTA have been demonstrated for a range of clinical microorganisms that include Gram-negative and -positive bacteria, yeasts, amoeba, and fungi. The integrity of the outer leaflet of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is maintained by hydrophobic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) interactions and LPS-protein interactions. Divalent cations such as Mg2+ are essential for stabilizing the negative charges of the oligosaccharide chain of the LPS component. EDTA has been shown to remove Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions from the outer cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria, thereby liberating up to 50% of the LPS molecules and exposing phospholipids of the inner membrane, enhancing the efficacy of other antimicrobials.33 Similarly, the effect of EDTA on yeasts is said to act by complexing with the Mg and Ca ions of the membrane with the different efficacies of EDTA being attributed to the different yeast species. This effect could be due to the subtle differences in the phospholipid composition of the membranes. The antifungal activity of EDTA is said to be likely via the inhibitory affect on growth causing fungal death by competing with siderophores for any of the trace iron and calcium ions that are essential for the maintenance of the life cycle of fungi.34

Control of biofilms with EDTA

Methods presently employed for preventing and eliminating biofilms are limited specifically in their efficacy on mature well-established biofilms with a complex polymicrobial microbiology. Despite this a number of antibiofilm formulations and technologies have demonstrated efficacy. These include lytic enzymes, which are thought to breakdown the EPS, use of bacteriophages, ultrasonic waves, electrolytic agents, quorum-sensing blocking agents, maggot therapy, topical negative pressure, and gallium compounds. Aside from these, over the last decade, EDTA has demonstrated very good efficacy on biofilms when used by itself as tEDTA.

At low concentrations EDTA has been shown to prevent biofilms by inhibiting the adhesion of bacteria.35 Furthermore, it has also been shown to reduce biofilm colonization and proliferation.36 A study by Juda et al.37 demonstrated that biofilm formation could be inhibited, after 72 h by treatment, with 2 mM EDTA. A later study by O'May et al.38 showed that EDTA was dose-dependent in its efficacy in both preventing and reducing biofilm development. Studies by Percival et al.39 reported a significant reduction in biofilms when treated with different EDTA compositions and solutions. A later study by Banin et al.36 demonstrated that treatment with 50 mM EDTA resulted in biofilm dissolution. Lambert et al.5 has shown a nonlinear relationship between a range of antimicrobials and EDTA.

The action of EDTA may enhance the therapeutic effect of other antimicrobials by disrupting the biofilm structure in which the target microorganisms are encased. This has been reported by Percival et al.40

Use of EDTA in wound care

Commercially available wound care products that contain EDTA include RescuDerm® (NociPharm, Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada) and Biostep® (Smith & Nephew Wound Management, Inc., Largo, FL). RescuDerm is available as a water-soluble gel that contains 0.1% EDTA. In addition to EDTA it contains acetic acid, citric acid, and carbopol. The antibiofilm ability of RescuDerm has been demonstrated on in vitro grown Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus epidermis biofilms.41 Furthermore, Martineau and Dosch42 demonstrated the ability of RescuDerm to prevent P. aeruginosa biofilm in full-thickness wound models in rats.

The Biostep collagen dressing is an MMP inhibiting dressing.2 With this technology it could be assumed that EDTA acts to chelate cations, thereby enzymatic activity, which is known to be contributing to wound inflammation. Further, EDTA would provide antibiofilm ability by chelating calcium and magnesium ions, which maintain the structure of the biofilm, and remove iron which is vital to microbial virulence and pathogenicity. Interestingly Biostep-Ag® has been developed and commercialized. The combination of EDTA and silver is known to have a significant antibiofilm ability as reported in the patent application by Percival et al.40

Summary

EDTA, in particular tEDTA, clearly has both antimicrobial and antibiofilm properties.43,44 Furthermore, when combined with different antimicrobials its synergistic ability for enhancing the antimicrobial efficacy is also evident. As nonhealing wounds are a direct result of the presence, persistence, and growth of pathogenic biofilms EDTA could be very useful not only for the removal of biofilms, when used by itself, but also when used alongside appropriate antimicrobials and surfactants. tEDTA's excellent proven safety and antimicrobial/antibiofilm ability makes it an ideal candidate for use in the development of future antibiofilm technologies.

Take-Home Messages.

• EDTA, in particular tEDTA, has been shown to have antimicrobial and antibiofilm abilities.

• EDTA is a very good potentiating and synergistic agent when used in conjunction with antimicrobials.

• The form in which sodium-based EDTA takes in solution is pH dependent.

• Gram-negative bacterial cell walls in particular are disrupted with EDTA.

• The affinity of EDTA toward metal ions (in particular divalent ions) is high leading to the breakdown of a biofilm.

• The EPS, which makes up approximately 80% of the biofilm structure, is disrupted by EDTA.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EPS

extracellular polymeric substance

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- tEDTA

tetrasodium EDTA

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

No funding was obtained for this review article.

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

No competing financial interests exist. The content of this article was expressly written by the authors listed. No ghostwriters were used to write this article.

About the Authors

Simon Finnegan obtained his MCHEM in Biological Chemistry in 2010 from the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom. Since then, Simon has undertaken a DTC-TERM PhD position at the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom, designing novel silicones to be used in currently available wound dressings in collaboration with Scapa healthcare. Steven L Percival holds a PhD in medical microbiology and biofilms, a BSc in Applied Biological Sciences, Postgraduate Certificate in Education, diploma in Business Administration, an MSc in Public Health, and an MSc in Medical and Molecular Microbiology. Early in his career, Steven held R&D and commercial positions at The British Textile Technology Group Plc, followed by 6 years as a senior university lecturer in medical microbiology, and later the positions of Director of Research and Development and Chief Scientific Officer at Aseptica, Inc. and senior clinical fellowships at the Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, and Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust, Leeds, United Kingdom. More recently, Steven held senior R&D positions at Bristol Myers Squibb, Advanced Medical Solutions PLC. In 2011, Steven joined Scapa Healthcare PLC as Vice President of Global R&D, Healthcare. He has written over 300 scientific publications and conference abstracts on biofilms, antimicrobials, and infection control and has authored and edited seven textbooks. He also holds the position of honorary Professor in the Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease and Surface Science Research Centre at the University of Liverpool.

References

- 1.Guardabassi L, Houser GA, Frank LA, Papich MG. Guidelines for antimicrobial use in dogs and cats. Guide to antimicrobial use in animals 2008;183–206 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dere K, et al. The 21st century treatment of venous stasis ulcers. Long-Term Care Interface 2006:34–37 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomsen TR, Hall-Stoodley L, Moser C, Stoodley P. The role of bacterial biofilms in infections of catheters and shunts. In: Bjarnsholt Thomas, Jensen Peter Østrup. Moser Claus, Høiby Niels, eds. Biofilm Infections. New York: Springer, 2011:91–109 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoodley P, Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, et al. Biofilms, biomaterials, and device-related infections. In: Ratner BD, Hoffman AS, Schoen FJ, Lemons JE, eds. Biomaterials Science an Introduction to Materials in Medicine, 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Elsevier, 2012:565–583 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert RJW, Hanlon GW, Denyer SP. The synergistic effect of EDTA/antimicrobial combinations on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Appl Microbiol 2004;96:244–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarty S, Jones EM, Finnegan S, Woods E, Cochrane CA, Percival SL. Wound infection and biofilms, Chapter 18. In: Percival SL, Williams DW, Randle J, Cooper T, eds. Biofilms in Infection Prevention and Control. Boston: Academic Press, 2014:339–358 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas J, Motlagh H, Povey S. The role of micro-organisms and biofilms in dysfunctional wound healing. Adv Wound Repair Ther 2011;39 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inngjerdingen K, Nergard CS, Diallo D, Mounkoro PP, Paulsen BS. An ethnopharmacological survey of plants used for wound healing in Dogonland, Mali, West Africa. J Ethnopharmacol 2004;92:233–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purner SK, Babu M. Collagen based dressings—a review. Burns 26:54–62. 69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Percival SL, Dowd S. The microbiology of wounds. In: Percival SL, Cutting K, eds. Microbiology of Wounds. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2010:187–218 [Google Scholar]

- 11.James GA, Swogger E, Wolcott R, et al. Biofilms in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhoads DD, Wolcott RD, Percival SL. Biofilms in wounds: management strategies. J Wound Care 2008;17:502–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Percival SL, Hill KE, Williams DW, Hooper SJ, Thomas DW, Costerton JW. A review of the scientific evidence for biofilms in wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2012;20:647–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis SC, Ricotti C, Cazzaniga A, et al. Microscopic and physiologic evidence for biofilmassociated wound colonization in vivo. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Percival SL, Bowler PG, Dolman J. Antimicrobial activity of silver-containing dressings on wound microorganisms using an in vitro biofilm model. Int Wound J 2007;4:186–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McSwain BS, Irvine RL, Hausner M, Wilderer PA. Composition and distribution of extracellular polymeric substances in aerobic flocs and granular sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005;71:1051–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehrlich GD, Hu FZ, Shen K, et al. Bacterial plurality as a general mechanism driving persistence in chronic infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005;437:20–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metzger U, Lankes U, Fischpera K, Frimmel FH. The concentration of polysaccharides and proteins in EPS of Pseudomonas putida and Aureobasidum pullulans as revealed by 13C CPMAS NMR spectroscopy. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2009;85:197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wingender J, Neu TR, Flemming HC. Extraction of EPS. In: Wingender J, Neu TR, Flemming HC, eds. Microbial Extracellular Polymeric Substances. Berlin: Springer, 1999:49–69 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Root JL, McIntyre OR, Jacobs NJ, Daghlian CP. Inhibitory effect of disodium EDTA upon the growth of Staphylococcus epidermidis in vitro: relation to infection prophylaxis of Hickman catheters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1988;32:1627–1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clarke NE, Clarke CN, Mosher RE. Treatment of angina pectoris with disodium ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid. Am J Med Sci 1960;232:654–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown MR, Richards RM. Effect of ethylenediamine tetraacetate on the resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to antibacterial agents. Nature 1965;207:1391–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kite P, Hatton D. U.S. Patent No. 8,703,053. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherertz RJ, Boger MS, Collins CA, Mason L, Raad II. Comparative in vitro efficacies of various catheter lock solutions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006;50:1865–1868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kite P, Hatton D. U.S. Patent No. 20,040,047,763. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kite P, Eastwood K, Percival SL. Assessing the effectiveness of EDTA formulations for use as a novel catheter lock solution for the eradication of biofilms. In: McBain A, Allison D, Pratten J, Spratt D, Upton M, Verran J, eds. Biofilms, Persistence and Ubiquity. Cardiff: Bioline, 2005:181–190 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh SE, Maillard JY, Russell AD, Catrenich CE, Charbonneau DL, Bartolo RG. Activity and mechanisms of action of selected biocidal agents on Gram-positive and-negative bacteria. J Appl Microbiol 2003;94:240–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma M, Visai L, Bragheri F, Cristiani I, Gupta PK, Speziale P. Toluidine blue- mediated photodynamic effects on staphylococcal biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008;52:299–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshizumi A, Ishii Y, Livermore DM, et al. Efficacies of calcium–EDTA in combination with imipenem in a murine model of sepsis caused by Escherichia coli with NDM-1 β-lactamase. J Infect Chemother 2013;19:992–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nezval J, Smékal E, Skotáková M, Rýc M. A contribution to studies on the influence of EDTA and Ca2+ on the antibacterial activity of neomycin on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Scr Med (Brno) 1965;38:311–316 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebashi S, Ebashi F, Fukie Y. The effect of EDTA and its analogues on glycerinated muscle fibers and myosin adenosinetriphosphatase. J Biochem 1960;47:54–59 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Douglas BE, Radanović DJ. Coordination chemistry of hexadentate EDTA-type ligands with M (III) ions. Coord Chem Rev 1993;128:139–165 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leive L. Release of lipopolysaccharide by EDTA treatment of E. coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1965;21:290–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amich J, Calera JA. Zinc acquisition: a key aspect in Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. Mycopathologia (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang Y, Gu W, McLandsborough L. Low concentration of ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) affects biofilm formation of Listeria monocytogenes by inhibiting its initial adherence. Food Microbiol 2012;29:10–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banin E, Brady KM, Greenberg EP. Chelator-induced dispersal and killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells in a biofilm. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006;72:2064–2069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juda M, Paprota K, Jaloza D, et al. EDTA as a potential agent preventing formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm on polichloride vinyl biomaterials. Ann Agric Environ Med 2008;15:237–241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'May CY, Sanderson K, Roddam LF, et al. Iron-binding compounds impair Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation, especially under anaerobic conditions. J Med Microbiol 2009;58:765–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Percival SL, Kite P, Eastwood K, et al. Tetrasodium EDTA as a novel central venous catheter lock solution against biofilm. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2005;26:515–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Percival SL, Bowler P, Parson D. (2005) Antimicrobial composition. US/WO patent is http://www.google.com.bz/patents/WO2007068938A2?cl=en

- 41.Martineau L, Dosch HM. Biofilm reduction by a new burn gel that targets nociception. J Appl Microbiol 2007;103:297–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martineau L, Dosch HM. Management of bioburden with a burn gel that targets nociceptors. J Wound Care 2007;16:157–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kite P, Eastwood K, Sugden S, Percival SL. Use of in vivo-generated biofilms from hemodialysis catheters to test the efficacy of a novel antimicrobial catheter lock for biofilm eradication in vitro. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42:3073–3076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Percival SL, Sabbuba NA, Kite P, Stickler DJ. The effect of EDTA instillations on the rate of development of encrustation and biofilms in Foley catheters. Urol Res 2009;37:205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wooley RE, Jones MS. Action of EDTA-Tris and antimicrobial agent combinations on selected pathogenic bacteria. Vet Microbiol 1983;8:271–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ayres HM, Payne DN, Furr JR, Russell AD. Effect of permeabilizing agents on antibacterial activity against a simple Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. Lett Appl Microbiol 1998;2:79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]