Abstract

After long periods of deforestation, forest transition has occurred globally, but the causes of forest transition in different countries are highly variable. Conservation policies may play important roles in facilitating forest transition around the world, including China. To restore forests and protect the remaining natural forests, the Chinese government initiated two nationwide conservation policies in the late 1990s -- the Natural Forest Conservation Program (NFCP) and the Grain-To-Green Program (GTGP). While some studies have discussed the environmental and socioeconomic effects of each of these policies independently and others have attributed forest recovery to both policies without rigorous and quantitative analysis, it is necessary to rigorously quantify the outcomes of these two conservation policies simultaneously because the two policies have been implemented at the same time. To fill the knowledge gap, this study quantitatively evaluated the effects of the two conservation policies on forest cover change between 2001 and 2008 in 108 townships located in two important giant panda habitat regions -- the Qinling Mountains region in Shaanxi Province and the Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary in Sichuan Province. Forest cover change was evaluated using a land-cover product (MCD12Q1) derived from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS). This product proved to be highly accurate in the study region (overall accuracy was ca. 87%, using 425 ground truth points collected in the field), thus suitable for the forest change analysis performed. Results showed that within the timeframe evaluated, most townships in both regions exhibited either increases or no changes in forest cover. After accounting for a variety of socioeconomic and biophysical attributes, an Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression model suggests that the two policies had statistically significant positive effects on forest cover change after seven years of implementation, while population density, percent agricultural population, road density, and initial forest cover (i.e. in 2001) had significant negative effects. The methods and results from this study will be useful for continuing the implementation of these conservation policies, for the development of future giant panda habitat conservation projects, and for achieving forest sustainability in China and elsewhere.

Keywords: Conservation Policy, Forest Cover Change, Panda Habitat Region, China

INTRODUCTION

Unprecedented rates of human population growth and other factors (e.g. timber harvest, cropland cultivation, infrastructure construction) have caused the conversion of natural forests to other land cover types across the world (Myers 1990, Pahari and Murai 1999, Carr 2004, 2005). However, while the overall amount of forest cover has been declining worldwide, an opposite trend -- forest expansion -- started to occur in France in the late 18th century (Mather 1992), and then spread to other European, North American and Asian countries (Totman 1986, Foster et al. 1998). With the spread of industrialization and urbanization, the trend of increase in forest cover also appeared later in many developing countries across the world. For instance, four major developing countries in Asia -- China, India, Vietnam, and Bangladesh -- have been experiencing forest regeneration since the 1980s (Rudel 2005, Mather 2007). During recent decades, a similar trend of positive forest cover change has also been identified in Central and South American countries such as Mexico, Ecuador, and Brazil (Klooster 2003, Baptista and Rudel 2006, Farley 2007). This turning point of forest cover change from negative to positive was termed ‘forest transition’ (Mather 1992, Mather et al. 1998, Mather et al. 1999, Mather and Fairbairn 2000, Mather 2004).

Forest transition has been reported for many places around the world, and has been documented at length (Mather 1992, Grainger 1995, Mather and Needle 1998, Rudel 1998, Rudel et al. 2005, Mather 2007, Barbier et al. 2010, Rudel et al. 2010). In addition, an extensive body of literature exists on the many factors that play important roles as determinants of forest transition across the world (Kaimowitz 1997, Foster and Rosenzweig 2003, Klooster 2003, Perz and Skole 2003, Nagendra et al. 2005, Pan and Bilsborrow 2005, Lambin and Meyfroidt 2010). But two arguments have been suggested to generalize the observed patterns (Rudel 1998, Rudel et al. 2005). The first one establishes that deforestation raises the price of wood and wood products, which not only induces people to harvest the remaining primary forests but also encourages them to plant more trees (Prunty 1956, Hart 1968, 1980, Sedjo and Clawson 1983, Royer 1987, Rush 1991, Haeuber 1993, Fairhead and Leach 1995, Hardie and Parks 1996, Walters 1997). The second one states that industrialization creates many off-farm job opportunities that attract laborers to shift from farm to off-farm economic activities, leading to the abandonment of marginal farmland and its re-conversion to forests (Hart 1968, Bentley 1989). However, this binary rationale (i.e., wood scarcity and economic development) does not explain all forest-transition phenomena. A variety of causal factors (driving forces) that operate under different environmental, socioeconomic, and political contexts are also important (Mather 2007), since neither development nor forest plantation alone can guarantee the emergence of a forest transition (Klooster 2003, Perz and Skole 2003, Perz 2007). Therefore, it is important to develop a thorough understanding of the driving forces behind forest transitions under different contexts.

Governments play important roles in facilitating forest transition by establishing different mechanisms (e.g., policies) that try to preserve and/or restore forest cover (Grainger 1995, Mather 2007, Nagendra 2007). Therefore, the role of government policies should not be overlooked in forest transition theory (Viña et al. 2011), particularly in developing countries (Jack et al. 2008). As a part of government activities, Payments for Environmental (or Ecosystem) Services (PES) have emerged globally during the past few decades (Ferraro and Kiss 2002). These programs provide direct (e.g. land purchases, leases, and easements) or indirect (i.e. alternative economic and social benefits) incentives to individuals or communities for mitigating the overexploitation of natural resources and stopping the degradation of natural systems associated with them (Ferraro and Kiss 2002). However, many externalities (e.g. natural disasters and economic recession) may lower the cost-effectiveness of indirect approaches (Ferraro 2001, Ferraro and Kiss 2002, Ferraro and Simpson 2002). Therefore, direct incentives have become prevalent, and more direct conservation payment programs have been initiated by governments and international non-governmental organizations around the world (Milne and Niesten 2009). These programs not only reward local communities for conservation activities, but also help them to develop alternative income opportunities (James et al. 1999, Ferraro 2001).

The demands of its large population and booming economy have caused deforestation and many other environmental problems in China, particularly during the last 60 years (Liu 2010). Excessive timber harvest of natural forests and reclaiming farmland on hillsides of the upper reaches of the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers are considered the main reasons for the frequent droughts and floods during the 1990’s in the Yangtze and Yellow rivers floodplain areas (World Wildlife Fund 2003, Liu and Diamond 2005, Hu et al. 2006); which have demonstrated the urgency of stopping deforestation and expanding the areas under forest cover (World Wildlife Fund 2003). But it was only after suffering severe droughts in 1997 and huge floods in 1998 (Weyerhaeuser et al. 2005, Liu et al. 2008) that the Chinese government initiated two nationwide PES programs [the Natural Forest Conservation Program (NFCP) and the Grain-to-Green Program (GTGP) in 1998 and 1999 respectively] to restore the degraded forest ecosystems.

The main goals of the NFCP and GTGP are to conserve (e.g., through logging bans) and restore (through afforestation and reforestation) forests in ecologically sensitive areas (e.g., areas with steep slopes). Details of these programs have been summarized in previous studies (Zhang et al. 2000, Xu et al. 2006, Liu et al. 2008, Chen et al. 2009). Government reports declare that both conservation policies have achieved the established goals. For instance, it has been reported that by the end of 2008, the NFCP had protected around 108 million ha of natural forests and planted about 5.7 million ha with trees (State Forestry Administration 2009a). It has also been reported that by the end of 2008, about 9.1 million ha of cropland in steep areas and 13.6 million ha of barren land have been planted with trees through the GTGP (State Forestry Administration 2010a). In addition, results of the 7th national forest resources survey (2004 through 2008) showed that forest cover in China grew steadily since the previous survey, from 18.21% of the country’s area by the end of 2003 to 20.36% by the end of 2008 (State Forestry Administration 2010b).

These two conservation programs have drawn worldwide attention due to their operating scales, amount of public investments, and environmental implications (Xu et al. 2000, Zhao et al. 2000, Ye et al. 2003, Xu et al. 2004, Shen et al. 2006, Uchida et al. 2007, Wang et al. 2007, Xu et al. 2007, Liu et al. 2008, Uchida et al. 2009, Cao et al. 2010). However, most published studies have focused on the evaluation of social, economic, and ecological effects of each of these programs independently, and acting at either the national level or the household level (Uchida et al. 2007, Xu et al. 2007, Liu et al. 2008), while very few studies have been conducted at township and county levels (Trac et al. 2007, Zhou et al. 2007). The township level, in particular, is highly relevant because townships constitute the basic implementation unit of the NFCP and GTGP (Zhu and Feng 2003). In addition, township is the basic stratum of the overall 5-level planning system (i.e. National-Provincial-City-County-Township) for land use in China (Ou et al. 2002). As a basic administrative level, township-level statistical data are often collected each year, which are not only an important data source of statistical yearbooks for higher administrative levels (e.g. county, province), but also provide relatively sufficient, proximate and accurate socioeconomic indicators that can be used for identifying driving forces of land-cover change. Township governments are in charge of making specific annual plans based on socioeconomic and biophysical conditions of the township, as well as tasks directly assigned by higher level governments (Zhu and Feng 2003). So each township may have different specific implementation schemes under the general regulation, which may produce various outcomes (e.g., differential changes in forest cover). In addition, very few studies have evaluated the simultaneous environmental effects of these two programs (Viña et al. 2011). This is important since conservation policies, such as the NFCP and GTGP, together with other driving forces (e.g. demographic, economic, technological, cultural and biophysical) may be some of the most important determinants of land use/cover change (Turner et al. 1993, Geist and Lambin 2001). As budgets for conservation programs are usually limited, it is absolutely crucial to evaluate the effectiveness of conservation programs in different contexts, which will guarantee scarce funds to go as far as possible in achieving conservation goals (James et al. 1999, Ferraro and Pattanayak 2006, Chen et al. 2010).

The main goal of this study was to evaluate the dynamics of forest cover at township level (a basic administrative and management unit in China) and their relations with the simultaneous implementation of NFCP and GTGP. Specifically, the study attempted to answer three questions: (1) What are the patterns of forest cover change since the implementation of conservation policies? (2) What driving forces underlie these forest cover change patterns? (3) Do conservation policies have positive effects on forest cover?

METHODS

Study Area

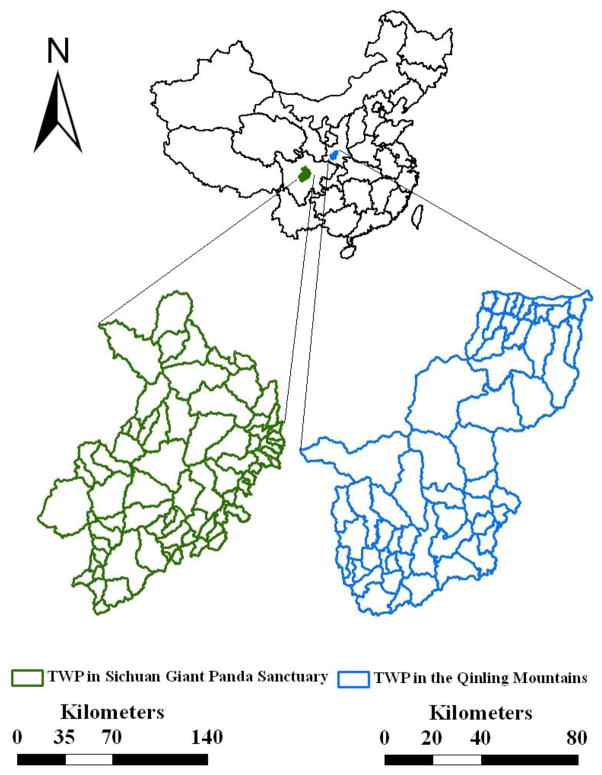

The study area is composed of two regions located in two different provinces. The first region is located in the middle part of the Qinling Mountains, Shaanxi Province. It includes 57 townships in three counties (Zhouzhi, Foping, and Yang). The second study region is the UNESCO Giant Panda Sanctuary, located in Sichuan province, and includes 72 townships in twelve counties (Baoxing, Chongzhou, Dayi, Dujiangyan, Kangding, Li, Luding, Lushan, Qionglai, Tianquan, Wenchuan, and Xiaojin) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Two study regions and their locations in China (Left: Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary; Right: the Qinling Moutains).

The study area includes two parts, one is green boundary map on the left that is the Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary including 72 townships in twelve counties; the other is blue boundary map on the right that is another study region in the Qinling Mountains of Shaanxi Province including 57 townships within three counties. Of the 129 townships, 108 townships were included in the final analysis while the remaining 21 were excluded due to reasons such as data availability.

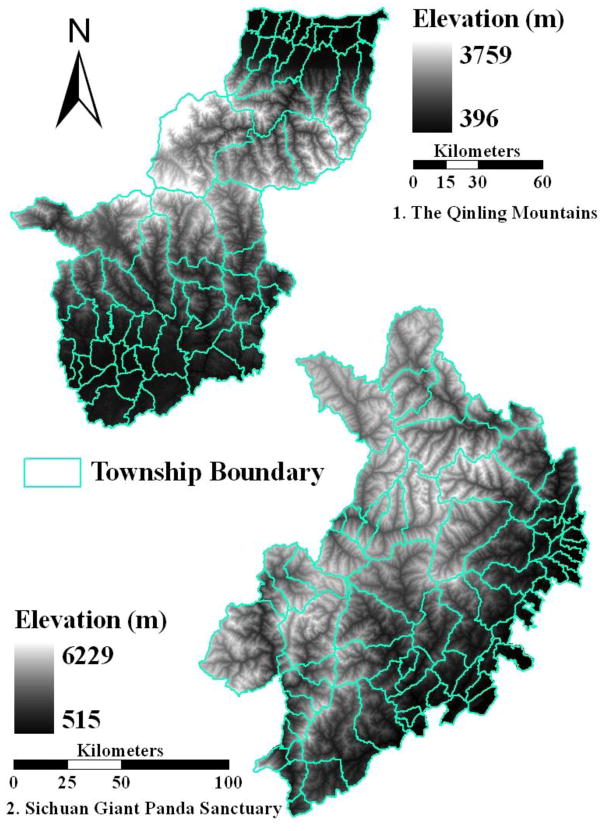

The Qinling Mountains are an important landmark in China. They not only constitute the natural boundary between southern and northern China, but also divide the Yangtze and Yellow River basins (Pan et al. 1988, Loucks et al. 2003). The Qinling Mountains are also a region with abundant biodiversity and home to many rare species, including the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Approximately twenty percent of all wild giant pandas (ca. 1,600 individuals) live in the Qinling Mountains (State Forestry Administration 2006). This region has been recognized as the one of the Global 200 Ecoregions defined by WWF (Olson et al. 2001). The elevation of the Qinling Mountains ranges from less than 1000 m to 3750 m (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Elevation ranges of the two study regions (1. The Qingling Mountains; 2.Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary).

The elevation raster data obtained from a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM). A continuous color legend was employed to show elevation change in both study regions. Areas with darker color have lower elevation. The elevation of the Qinling Mountains ranges from 396 m to 3750 m; compared with elevation of the Qinling Mountains region, the Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary has higher elevation difference, from the lowest 515 m to the highest 6229 m.

The Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary was established as a member of the UNESCO World Heritage System in 2006. It is not only a refuge to diverse vertebrate and plant species, but also home to more than thirty percent of the entire wild giant panda population (State Forestry Administration 2006). In fact, the region has been classified as part of the world’s top 25 Biodiversity Hotspots (Myers et al. 2000, Liu et al. 2003) and also constitutes one of the Global 200 Ecoregions defined by WWF (Olson et al. 2001). The elevation within the Sanctuary varies significantly (from ca. 400 to 6,200 m) (Figure 2).

In addition to their enormous conservation value, both regions are ideal for evaluating the effects of conservation policies on forest cover changes. First, both areas suffered intensive commercial logging before 1998, when the national logging ban was implemented (Pan et al. 1988, Yang and Li 1992). In 2000, the NFCP and GTGP started in both regions. Second, townships in both regions have various biophysical attributes and socioeconomic characteristics that may cause different effects brought by similar conservation efforts, thus contribute to different patterns of forest cover change. Third, as most townships in the two study regions have systematically published township-level statistical data in multiple consecutive years, it is possible to obtain the necessary socioeconomic data at the township level. Finally, both regions include important giant panda habitat, so the study of forest cover change will provide information useful for giant panda habitat conservation because forest cover is an essential part of panda habitat.

Forest Cover Change Detection

The MODIS Land Cover Type product (MCD12Q1 Yearly L3 Global 500 m SIN Grid) was used for assessing forest cover changes. The International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) scheme, the primary one of five land cover classification schemes of this product, was used since it is specifically designed for the improvement of large-scale vegetation models needed for global and regional assessments (International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme 2010) and has been proven to exhibit high accuracy in identifying land-cover types in China, especially after aggregating the original 17 classes into few combined land-cover classes (Wu et al. 2008, Ran et al. 2010).

Eight consecutive years of the MODIS Land Cover Type product (from 2001 to 2008) were downloaded from the Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC) (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/lpdaac/products/modis_products_table). The 17 different land-cover classes (i.e., water, evergreen needleleaf forest, evergreen broadleaf forest, deciduous needleleaf forest, deciduous broadleaf forest, mixed forest, closed shrublands, open shrublands, woody savannas, savannas, grasslands, permanent wetlands, croplands, urban and built-up, cropland/natural vegetation mosaic, snow and ice, and barren or sparsely vegetated) of the IGBP classification scheme were reclassified into two categories (forest and non-forest).

A total of 425 ground-truth plots with land-cover type information collected in both study regions (Qinling and Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary) from 2004 to 2007 were used to evaluate the accuracy of the forest/non-forest reclassification of the IGBP scheme. Among them, 175 and 250 points were collected in the Qinling Mountains and the Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary, respectively. The user’s accuracy for non-forest and forest areas was 84% and 87% respectively, and the overall accuracy was 87% (Table 1). Thus, the IGBF land-cover product merged into forest/non-forest cover provides sufficient classification accuracy to be used for detecting forest cover change in the two study regions.

Table 1.

Error Matrix of the MODIS derived IGBP classification scheme, merged into two land cover classes (forest and non-forest). The matrix was generated using 425 ground truth points collected in the field between 2004 and 2007.

| Ground Truth Points | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-forest | Forest | Row Total | ||

| MODIS product | Non-forest | 16 | 3 | 19 |

| Forest | 53 | 353 | 406 | |

| Column Total | 69 | 356 | 425 | |

| User’s Accuracy | ||||

| Non-forest = 16/19 = 84% | ||||

| Forest = 353/406 = 87% | ||||

| Overall Accuracy = (16+353)/425 = 87% | ||||

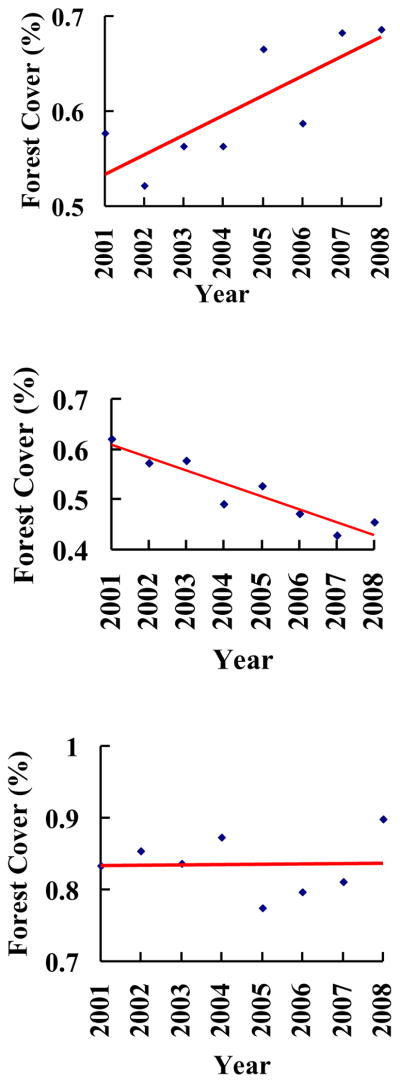

Forest cover information from each township was extracted from the MODIS Land-Cover product by using a corresponding digitized township-boundary file. The proportion of each township under forest cover in each of the eight years available (2001 through 2008) was calculated by dividing the number of forest pixels by the total number of pixels within each township’s boundary. Considering the inter-annual variability observed in the MODIS Land-Cover Type product, a linear-regression analysis was employed on a per-township basis to detect the trend of forest cover change between 2001 and 2008. If the regression line showed a significant (p<0.05) trend (either positive or negative) of percent forest cover change with respect to time (i.e., year), then the values of forest cover change (Δ forest) between 2001 and 2008 were calculated per township based on the empirical equation obtained by each regression analysis., In contrast, if the regression line showed a non-significant trend, the difference of forest cover change between 2001 and 2008 was considered as 0. Examples of these trends in three different townships are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Examples of three types of forest cover change.

Three representative townships were chosen to illustrate three trends of forest cover change. For each township, X-axis and Y-axis represent year and percentage of forest cover, respectively; each black dot represents percentage of forest cover of the township in specific year between 2001 and 2008; the red line was drawn by regression analysis of values of X and Y, which shows trend of forest cover change of each township from 2001 to 2008. Top: Daheba Township had a significant increase (+ Δ forest); middle: Shiguan Township had a significant decrease (− Δ forest); bottom: Wushan Township had insignificant change (Δ forest = 0).

Forest Cover Change Attribution

An Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression model was employed to estimate the effects of socioeconomic factors, biophysical factors, and conservation implementation status (GTGP and NFCP) on the forest cover change. In the model, the dependent variable was forest cover change at the township level between 2001 and 2008. The OLS regression was defined as:

| (1) |

Where y is the dependent variable, β is the vector of coefficients, X is the set of dependent variables, and ε is the vector of random error terms. The selection of potential explanatory variables (e.g. socioeconomic and biophysical) was based not only on the approaches undertaken in previous studies by combining remote-sensing data with spatially-explicit information (Pahari and Murai 1999, Mertens et al. 2000, Gautam et al. 2004, Ali et al. 2005, Armenteras et al. 2006, Chowdhury 2006, Ferreira et al. 2007), but also on the availability of data for the entire study area. Both demographic and economic data at township level were acquired from the statistical yearbooks of each county. Information on the implementation of the NFCP and GTGP (e.g. implementation date, total planned area, and total implemented area) was obtained from government sources (i.e., Forestry Bureau, Center of NFCP and Office of GTGP) and from published reports of the NFCP and GTGP implementation, when available. Topographic data (i.e. elevation and slope) were obtained from a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) (90m × 90m) (Rabus et al. 2003). Data on elevation and slope were averaged by all pixel values within each township boundary in order to obtain specific topographic attribute (i.e. slope and elevation) for each township. Table 2 shows the explanatory variables included in the regression model.

Table 2.

Explanatory variables used in the Ordinary Least Square regression model developed in the study

| Variable | Definition | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| POPDEN | population density of a township | individuals/km2 |

| PAPOP | percentage of agricultural population | % |

| HHSIZE | average household size | number of individuals/household |

| PCROPL | percentage of cropland area within the township boundary | % |

| UPCROP | unit production of cropland | ton/mu* |

| FOR2001 | forest cover in year 2001 | % |

| ELEVATION | average elevation of the township | m |

| SLOPE | average slope of the township | ° |

| RDDEN | road density of each township | km/km2 |

| GTGP | percentage of the GTGP area within a township boundary | % |

| NFCP | NFCP implementation status; a dummy variable with 0 representing non-NFCP implementation and 1 NFCP implementation; | N/A |

| REGION | regional difference; a dummy variable with 1 representing townships in the Qinling Mountain region, and 0 representing townships in the Giant Panda Sanctuary. | N/A |

1 mu = 1/15 ha

In order to reduce the impacts of multicollinearity on individual variables of the regression model (Lipovetsky and Conklin 2001, Ott and Longnecker 2001), a collinearity diagnostic was conducted. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and tolerance and multiple correlation analysis were combined to make a final selection of variables to be retained. A common rule of thumb is that if VIF is higher than 5, then multi-collinearity is of concern (O’Brien 2007). Moreover, based on our knowledge of the study regions and a correlation matrix of all variables (Table 4), the first three variables [i.e. SLOPE (slope), PCROPL (percentage of cropland) and ELEVATION (elevation)] exhibiting higher VIF values were excluded (Table 3). POPDEN (population density) is a direct indicator of human pressure on land-cover change, which can reflect the level of human demand [i.e. PCROPL (percentage of cropland)] in our study regions. Therefore, it is reasonable to retain POPDEN. Moreover, SLOPE and ELEVATION had higher correlation with REGION (regional difference) and both variables are significantly different between the two regions (p<0.01) but relatively consistent within each region. So REGION can be used as a proxy of the topographic difference in the two study regions. Except these three excluded variables, all other variables were retained in the regression model.

Table 4.

Correlation Matrix of Pre-Selected Explanatory Variables

| POPDEN | PAPOP | HHSIZE | PCROPL | UPCROP | ELEVAT | SLOPE | RDDEN | GTGP | NFCP | REGION | FOR2001 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POPDEN | 1.0000 | |||||||||||

| PAPOP | −0.3840 | 1.0000 | ||||||||||

| HHSIZE | −0.3078 | 0.5123 | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| PCROPL | 0.8399 | −0.1332 | −0.1886 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| UPCROP | 0.3339 | −0.0598 | −0.2081 | 0.3340 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| ELEVATION | −0.4763 | 0.0319 | 0.3296 | −0.5517 | −0.5534 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| SLOPE | −0.7447 | 0.0608 | 0.3107 | −0.8513 | −0.3858 | 0.7392 | 1.0000 | |||||

| RDDEN | 0.4405 | −0.2331 | −0.1831 | 0.4885 | 0.2654 | −0.5412 | −0.6167 | 1.0000 | ||||

| PGTGP | 0.2304 | −0.0338 | −0.2506 | 0.2967 | 0.1687 | −0.5701 | −0.4839 | 0.4087 | 1.0000 | |||

| NFCP | −0.3846 | −0.0349 | 0.2018 | −0.3645 | −0.0725 | 0.3392 | 0.4588 | −0.1505 | −0.2235 | 1.0000 | ||

| REGION | 0.3413 | 0.1716 | −0.1944 | 0.4328 | 0.1176 | −0.6807 | −0.6217 | 0.2929 | 0.4453 | −0.4028 | 1.0000 | |

| FOR2001 | −0.5750 | 0.0474 | 0.0802 | −0.6675 | 0.1290 | 0.1003 | 0.5957 | −0.3293 | −0.2544 | 0.2649 | −0.2525 | 1.0000 |

Table 3.

Values of Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of All Pre-Selected Explanatory Variables

| Variable | VIF |

|---|---|

| SLOPE | 9.82 |

| PCROPL | 7.01 |

| ELEVATION | 6.42 |

| POPDEN | 5.27 |

| FOR 2001 | 3.69 |

| REGION | 2.85 |

| PAPOP | 2.42 |

| UPCROP | 2.13 |

| RDDEN | 2.09 |

| HHSIZE | 1.83 |

| GTGP | 1.81 |

| NFCP | 1.43 |

| Mean VIF | 3.90 |

After considering the results of multi-collinearity diagnostics, the specification of the final regression model was as follows:

| (2) |

Where Y is the forest cover change between 2001 and 2008 for each township, and Xk stands for the explanatory variables POPDEN, PAPOP (percentage of agricultural population), HHSIZE (household size), UPCROP (unit production of cropland), RDDEN (road density), GTGP (percentage of the GTGP area), NFCP (NFCP implementation status), REGION and FOR2001 (forest cover in year 2001), respectively; and ε is the term representing the vector of random errors. Since statistical yearbooks of 11 townships (5 townships in Lushan County and 6 townships in Dujiangyan County) in the Sichuan Panda Sanctuary were not available and the 10 townships in Zhouzhi County of Shaanxi Province are located in flat areas with neither forest cover present nor conservation policy implementation within their boundaries, a total of 108 townships (83.7 % of all townships in the two study regions) in 13 counties were selected for the final OLS model.

RESULTS

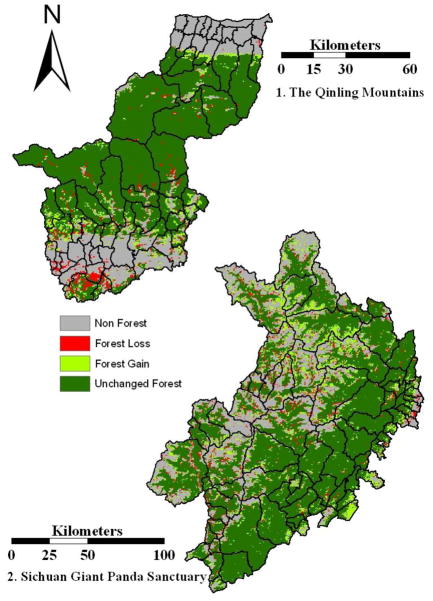

Across the entire study areas, after seven years of GTGP and NFCP implementation, the forest areas expanded and the non-forest areas decreased in many townships (Figure 4). Visually, many forest patches connected with each other and many non-forest patches disappeared. However, in both study regions, besides areas with forest gain, forest loss can still be observed, particularly in the lower part of Qinling Mountains region.

Figure 4. Forest cover change at pixel level from 2001 to 2008 (1. The Qinling Mountains; 2. The Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary).

Four different colors represent four types of land cover change from 2001 to 2008 in both study regions. Gray represents non-forest areas (i.e. non-forest in both 2001 and 2008); red represents areas with forest loss (i.e. from forest in 2001 to non-forest in 2008); light green represents areas with forest restoration (i.e. from non-forest in 2001 to forest in 2008); dark green represents area with stable forest cover (i.e. forest in both 2001 and 2008).

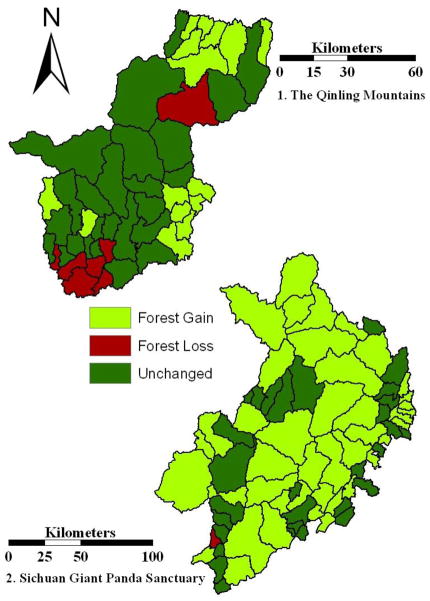

Results from the regression analysis of forest cover change vs. time at the township level showed that 43% of the townships (i.e., 46 out of 108) had a significant increase while 7% (i.e., 8 out of 108) had a significant decrease in forest cover change from 2001 to 2008. The remaining townships (i.e., 54 of 108) did not show significant changes in forest cover (Figures 5). Most of the townships in the Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary exhibited forest cover gains, while in the Qinling Mountains, most of the townships showed no change in forest cover. In addition, most of the townships that exhibited significant forest cover losses were located in the Qinling Mountains region (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Forest cover change at township level from 2001 to 2008 (1. The Qinling Mountains; 2. Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary).

Three colors represent three types of township with different trends of forest cover change. Townships assigned by light green means their forest cover increased from 2001 to 2008 (i.e. + Δ forest); townships assigned by dark green represent no change in forest cover from 2001 to 2008 (i.e. Δ forest = 0); townships assigned by red color means their forest cover decreased from 2001 to 2008 (i.e. − Δ forest).

Table 5 shows the results of the OLS model. Among the five socioeconomic variables, population density (POPDEN), percentage of agricultural population (PAPOP), and road density (RDDEN) had a significant negative effect on forest cover change. The initial forest cover in 2001 (FOR 2001) also showed a significant negative effect on forest cover change. In contrast, both conservation policy variables had significant positive effects on forest cover change.

Table 5.

Coefficients of the Ordinary Least Squares regression model developed at township level

| Variable Category | Variables | Coefficients | Std. Error | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic Variables | POPDEN | −0.011 | 0.006 | 0.069* |

| PAPOP | −16.650 | 8.120 | 0.043** | |

| HHSIZE | 3.159 | 2.163 | 0.147 | |

| UPCROP | 4.957 | 7.614 | 0.517 | |

| RDDEN | −0.014 | 0.006 | 0.029** | |

| Biophysical Attributes | FOR 2001 | −0.099 | 0.043 | 0.022** |

| REGION | −0.817 | 2.167 | 0.707 | |

| Conservation Policies | GTGP | 45.081 | 25.601 | 0.081* |

| NFCP | 5.180 | 3.021 | 0.090* | |

| Adjusted R2 = 0.129 | ||||

0.05<P < 0.1;

P < 0.05

All the 108 townships in the study area are partly or entirely located in the mountainous region and covered by one or both conservation policies. There are 13 townships covered by one conservation policy, including 12 townships that are only covered by the GTGP and 1 township only covered by the NFCP. All other townships are covered by both conservation policies. Among the 13 townships with single conservation policy implementation, six showed forest cover losses from 2001 to 2008, and two showed stable forest cover. Based on this small sample size, it is not possible to empirically quantify the effects of one vs two policies on forest cover change. However, theoretically the implementation of a single policy may produce less forest cover gain due to a smaller implementation area than two policies.

DISCUSSION

Results of the linear regression model show that forest cover change is best explained by multiple factors acting synergistically rather than by single-factor causation, which is in accordance with many other studies about causes of forest cover change (Burgess and Sharpe 1981, Southgate et al. 1991, Bawa and Dayanandan 1997, Geist and Lambin 2001). The township-level forest cover change map (Figure 5) shows that although both regions started implementing conservation policies at about the same time, they had quite different recovery patterns and processes. Most of the townships in the Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary experienced forest cover gains, while most of the townships in the Qinling Mountains showed unchanged forest cover. Historically, most changes in forest cover result from human activities (Houghton 1991, Meyer and Turner 1992, Jorgenson and Burns 2007, Carr 2008), so various demographic pressures may cause significant differences in forest cover change between the two study regions. Since township population density in the Qinling Mountains is significantly higher than in the townships of Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary (p<0.01), forests in the Qinling Mountains region may face higher human pressures than those in the Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary.

Moreover, results showed that demographic characteristics are important determinants of forest cover change, having significantly negative effects. This supports the negative relationship between forest cover and population pressure reported by previous studies (Allen and Barnes 1985, Carr et al. 2005, Jha and Bawa 2006). The change in population alters the demand for land and forests, which are expected to supply food, fuel, and environmental services for local people (Mikesell 1960, Allen and Barnes 1985, Williams 1989). Before conservation policies were implemented, larger populations meant more demands on natural resources (e.g. timber, fuelwood, and forestry products) and more land conversion from forest to non-forest. After 2000, both the NFCP and GTGP were implemented in these regions, and logging was strictly banned. Although large-scale commercial timber harvest has ceased and illegal logging has been controlled (Zhang 2006), higher population pressures may reduce the forest cover gains. In order to meet the demands of local people, fuelwood consumption and timber used in new housing construction still has a significant impact on forest restoration. A higher percentage of agricultural population may also cause greater dependency on fuelwood for cooking and heating (Krutilla et al. 1995). In addition, other activities, such as cultivation and grazing conducted by local agricultural populations, may also offset part of the forest gains brought about by conservation policy implementation.

As a development indicator, roads also had a significantly negative impact on forest cover change in the study regions. Many previous studies indicated that roads are considered an important factor behind deforestation and forest fragmentation (Young 1994, Pfaff 1999, Nagendra et al. 2003, Soares et al. 2004, Fearnside 2007, 2008). Roads not only directly impact forest resources through road construction (Laurance et al. 2009), but also have a key role in facilitating the exploitation of forest regions (Ali et al. 2005, Pfaff et al. 2007, Laurance et al. 2009). Thus, road networks, which provide market access to remote areas, may induce local people to exploit more natural resources. Moreover, road construction for timber harvesting sometimes provides access for agricultural populations in search of new land to clear and farm (Allen and Barnes 1985, Southgate et al. 1991, Nepstad et al. 2001, Soares et al. 2004, Fearnside 2007). In the study area, the road networks may have particularly negative effects on forest cover change. On the one hand, widening old roads and construction of new roads may directly cause forest cover losses. In both study regions, a new round of road-network extension projects named “roads to every village” has been conducted since 2005 (Sichuan Provincial People’s Government 2006). Many counties in both study regions have achieved the goal of connecting every village with paved roads (Y. Li, Pers. Obs.). On the other hand, with growing road networks and improved road conditions, many townships in both study regions have developed or are planning to develop tourism activities (Li and Han 2001, Fang 2002, Li 2004, He et al. 2008, Luo and Zheng 2008). For example, the number of tourists in Wolong Nature Reserve, one of the most important giant panda nature reserves in China and located within the Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuary, increased from 130,000 in 2000 to 206,100 in 2005 (He et al. 2008). The booming tourism causes more wood consumption in both study regions, since more fuelwood is required to meet demands of tourists (e.g. cooking, heating, making smoked pork) (Gaughan et al. 2008) and many conventional tourism facilities (e.g. restaurants, hotels) have been constructed, which usually consume fuelwood (Field Observation).

The initial forest cover often determined the level of implementation of conservation policies. In order to preserve species and their habitat or prevent flooding and soil erosion, local governments are under pressure to protect the remaining forests and implement conservation policies (Grainger 1995). Forest plantation is a fast and direct way to help forest recovery and reach the transition point (i.e., from forest cover loss to forest cover gain). In townships with a larger area of clear-/selectively-cut areas, barren lands, or sloping croplands it may be a priority to apply reforestation and afforestation methods such as tree planting and aerial seeding. On the contrary, in townships with larger areas of remaining forest, forest protection and surveillance will be applied first, and forest restoration will rely mainly on natural regeneration. Since reforestation and afforestation usually produce faster effects than natural regeneration during a short period, the townships with lower initial percent forest cover may have relatively greater forest cover gains as compared with other townships with larger initial percent forest cover.

Contrary to the effects of the previously described variables, in the study area both conservation policies had positive effects on forest cover change. In mountain regions, cropland is a major non-forest land cover type. The GTGP helps local farmer households to convert steep-slope cropland into ecological or economic forests. This program appears to contribute to forest cover gains in most townships with the GTGP implementation. Usually, fast-growing local tree species are selected for tree planting under the GTGP (Chen et al. In press). These planted tree species may not only benefit the environment (e.g., reduce soil erosion and increase tree cover) but also increase the income of enrolled local farmer households within a relatively short period of time (Zhang et al. 2003). In addition, substantial labor supplies have been released from agriculture and attracted to local off-farm work or even more urbanized regions through labor migration (Peng et al. 2007, Uchida et al. 2009), which not only enhance the conversion of abandoned marginal cropland to forest, but also reduce the pressure of local populations on natural resources (Peng et al. 2007, Qin 2010).

Compared with the single method (i.e. tree planting) of the GTGP, the NFCP consists of four different forest restoration/conservation methods (i.e. forest conservation and management, mountain closure, tree planting and aerial seeding). All methods should show positive effects on forest cover in the NFCP implementation areas.

CONCLUSIONS

After seven years of implementation, conservation policies seem to be achieving their goals of restoring forest cover and conserving natural forests (Liu et al. 2008). Most townships in the study area exhibited either forest regeneration or have effectively protected their remaining forests. Continuous conservation efforts through the GTGP and the NFCP are therefore important for preventing deforestation and forest degradation in China. Fortunatly, the GTGP was recently renewed for another eight years while the NFCP was renewed for another 10 years. However, results of the regression model suggest that demographic factors have significant negative effects on forest cover change. Specifically, population density and percentage of agricultural population were strongly and negatively related to forest cover change. In addition, as a proxy of development, road density also had significantly negative effects on forest cover change. Extension of road networks may not only directly result in forest cover losses but also increase wood consumption caused by tourism development and other types of forest exploitation. Although in some areas, road networks increase access to other types of energy (e.g. coal and electricity), in the study regions the use of coal and electricity as an alternative to fuelwood is still low (Wang et al. 2010). In order to mitigate the negative effects caused by the above driving forces and enhance the positive effects of conservation policies on forest cover change, local governments should consider implementing two additional actions. On the one hand, they should help local households switch their energy sources from fuelwood to others, such as electricity and methane. Generally, methane has the advantages of being cheap, easy to generate, and multifunctional, as it can be generated by fermentation of human and livestock waste, or of corn and/or wheat stalks, thus providing energy for cooking and heating. For the households that cannot switch from fuelwood to other energy sources, the government and non-governmental organizations (e.g. World Wide Fund for Nature) may help them change their stoves to fuelwood-saving types. Fortunately, both study regions have started to use these strategies to reduce the negative effects on forest cover change (World Wildlife Fund 2004, State Forestry Administration 2009b). On the other hand, besides energy substitution strategies, rural-urban labor migration may also reduce human impacts on forests. For this, local governments should provide training for local people in order to increase their skills to obtain job opportunities in urban areas.

Forest transition in China is not a unique case in Asia. India and Vietnam have also undergone forest transition during the last decade (Foster and Rosenzweig 2003, Meyfroidt and Lambin 2009). In addition, many other developing countries around the world have slowed down deforestation and may step into a forest transition within the near future (Henson 2005, Wannitikul 2005). Therefore, it is necessary to understand the underlying driving forces of these observed patterns and their ecological effects, which may contribute to understanding a possible emerging trend that would have important implications for future forest resources worldwide.

Finally, although conservation policies have shown positive effects on forest cover not only in the study area, but also in China as a whole (Liu et al. 2008), we should not ignore their potential global environmental implications (Liu and Raven 2010). Today, China has become a world-leading timber importer and wood product exporter (U.S. office of the Environmental Investigation Agency 2007). Implementation of forest conservation policies in China have raised global concerns that as a result of these policies, China’s timber import is exerting enormous pressures on the forests of other regions such as Southeast Asia (e.g. Burma and Indonesia), Madagascar, and eastern Russia, often in the form of illegal logging (Laurance 2008, Center for International Forestry Research 2010). Future research, therefore, needs to assess the effects of China’s domestic forest conservation policies on forest resources in other countries.

Acknowledgments

We thank Heming Zhang of Wolong National Nature Reserve in Sichuan Province and Yang Xu of Forestry Bureau of Hanzhong City in Shaanxi Province for the support with fieldwork logistics. Dong Chen and Ligui Wan for their invaluable assistance during field work. We are grateful to Runsheng Yin for helpful discussion. This study was supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

References

- Ali J, Benjaminsen TA, Hammad AA, Dick OB. The road to deforestation: An assessment of forest loss and its causes in Basho Valley, Northern Pakistan. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions. 2005;15:370–380. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JC, Barnes DF. The causes of deforestation in developing-countries. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 1985;75:163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Armenteras D, Rudas G, Rodriguez N, Sua S, Romero M. Patterns and causes of deforestation in the Colombian Amazon. Ecological Indicators. 2006;6:353–368. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista SR, Rudel TK. A re-emerging Atlantic forest? Urbanization, industrialization and the forest transition in Santa Catarina, southern Brazil. Environmental Conservation. 2006;33:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier EB, Burgess JC, Grainger A. The forest transition: Towards a more comprehensive theoretical framework. Land Use Policy. 2010;27:98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bawa KS, Dayanandan S. Socioeconomic factors and tropical deforestation. Nature. 1997;386:562–563. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley JW. Bread forests and new fields: the ecology of reforestation and forest clearing among small-woodland owners in Portugal. Journal of Forest History. 1989;33:188–195. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess RL, Sharpe DM, editors. Forest Island dynamics in man dominated landscapes. Springer; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cao SX, Wang XQ, Song YZ, Chen L, Feng Q. Impacts of the Natural Forest Conservation Program on the livelihoods of residents of Northwestern China: Perceptions of residents affected by the program. Ecological Economics. 2010;69:1454–1462. [Google Scholar]

- Carr DL. Proximate population factors and deforestation in tropical agricultural frontiers. Population and Environment. 2004;25:585–612. doi: 10.1023/B:POEN.0000039066.05666.8d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DL. Forest clearing among farm households in the Maya Biosphere Reserve. Professional Geographer. 2005;57:157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Carr DL. Migration to the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Guatemala: Why place matters. Human Organization. 2008;67:37–48. doi: 10.17730/humo.67.1.lvk2584002111374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DL, Suter L, Barbieri A. Population dynamics and tropical deforestation: State of the debate and conceptual challenges. Population and Environment. 2005;27:89–113. doi: 10.1007/s11111-005-0014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for International Forestry Research. Report. 2010. China’s timber imports raises concerns. [Google Scholar]

- Chen XD, Lupi F, An L, Sheely R, Viña A, Liu JG. Agent-based modeling of the effects of social norms on enrollment in payments for ecosystem services. Ecological Modeling. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2011.06.007. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XD, Lupi F, He GM, Liu JG. Linking social norms to efficient conservation investment in payments for ecosystem services. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:11812–11817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809980106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XD, Lupi F, Vina A, He GM, Liu JG. Using cost-effective targeting to enhance the efficiency of conservation investments in Payments for Ecosystem Services. Conservation Biology. 2010;24:1469–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury RR. Driving forces of tropical deforestation: The role of remote sensing and spatial models. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography. 2006;27:82–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fairhead J, Leach M. False forest history, complicit social analysis-rethinking some west-African envrionmental narratives. World Development. 1995;23:1023–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Fang YP. Ecotourism in Western Sichuan, China - Replacing the forestry-based economy. Mountain Research and Development. 2002;22:113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Farley KA. Grasslands to tree plantations: Forest transition in the andes of Ecuador. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2007;97:755–771. [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside PM. Brazil’s Cuiaba-Santarem (BR-163) Highway: The environmental cost of paving a soybean corridor through the amazon. Environmental Management. 2007;39:601–614. doi: 10.1007/s00267-006-0149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside PM. The Roles and Movements of Actors in the Deforestation of Brazilian Amazonia. Ecology and Society. 2008;13:22. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro PJ. Global habitat protection: Limitations of development interventions and a role for conservation performance payments. Conservation Biology. 2001;15:990–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro PJ, Kiss A. Ecology - Direct payments to conserve biodiversity. Science. 2002;298:1718–1719. doi: 10.1126/science.1078104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro PJ, Pattanayak SK. Money for nothing? A call for empirical evaluation of biodiversity conservation investments. Plos Biology. 2006;4:482–488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro PJ, Simpson RD. The cost-effectiveness of conservation payments. Land Economics. 2002;78:339–353. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira NC, Ferreira LG, Miziara F. Deforestation hotspots in the Brazilian Amazon: Evidence and causes as assessed from remot sensing and census data. Earth Interactions. 2007:11. [Google Scholar]

- Foster AD, Rosenzweig MR. Economic growth and the rise of forests. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2003;118:601–637. [Google Scholar]

- Foster DR, Motzkin G, Slater B. Land-use history as long-term broad-scale disturbance: Regional forest dynamics in central New England. Ecosystems. 1998;1:96–119. [Google Scholar]

- Gaughan AE, Binford MW, Southworth J. Tourism, forest conversion, and land transformations in the Angkor basin, Cambodia. Applied Geography. 2008;29:212–223. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam AP, Shivakoti GP, Webb EL. Forest cover change, physiography, local economy, and institutions in a mountain watershed in Nepal. Environmental Management. 2004;33:48–61. doi: 10.1007/s00267-003-0031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geist HJ, Lambin EF. What drives tropical deforestation? A meta-analysis of proximate and underlying causes of deforestation based on subnational case study evidence. LUCC report 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Grainger A. The forest transition: An alternative approach. Area. 1995;27:242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Haeuber R. Development and deforestation - Indian forestry in perspective. Journal of Developing Areas. 1993;27:485–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie IW, Parks PJ. Program enrollment and acreage response to reforestation cost-sharing programs. Land Economics. 1996;72:248–260. [Google Scholar]

- Hart JF. Loss and abandonment of cleared farm land in eastern united-states. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 1968;58:417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Hart JF. Land-use change in a piedmont county. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 1980;70:492–527. [Google Scholar]

- He GM, Chen XD, Liu W, Bearer S, Zhou SQ, Cheng LY, Zhang HM, Ouyang ZY, Liu JG. Distribution of economic benefits from ecotourism: a case study of Wolong Nature Reserve for Giant Pandas in China. Environmental Management. 2008;42:1017–1025. doi: 10.1007/s00267-008-9214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson IE. An assessment of changes in biomass carbon stocks in tree crops and forests in Malaysia. Journal of Tropical Forest Science. 2005;17:279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton RA. Tropical deforestation and atmospheric carbon-dioxide. Climatic Change. 1991;19:99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Hu CX, Fu BJ, Chen LD, Gulinck H. Farmer’s attitudes towards the Grain-for-Green programme in the Loess hilly area, China: A case study in two small catchments. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology. 2006;13:211–220. [Google Scholar]

- International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme. Refining plant functional classifications for earth system modeling. 2010 http://www.igbp.net/page.php?pid=369.

- Jack BK, Kousky C, Sims KRE. Designing payments for ecosystem services: Lessons from previous experience with incentive-based mechanisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:9465–9470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705503104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AN, Gaston KJ, Balmford A. Balancing the Earth’s accounts. Nature. 1999;401:323–324. doi: 10.1038/43774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha S, Bawa KS. Population growth, human development, and deforestation in biodiversity hotspots. Conservation Biology. 2006;20:906–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson AK, Burns TJ. Effects of rural and urban population dynamics and national development on deforestation in less-developed countries, 1990–2000. Sociological Inquiry. 2007;77:460–482. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimowitz D. Factors determining low deforestation: The Bolivian Amazon. Ambio. 1997;26:537–540. [Google Scholar]

- Klooster D. Forest transitions in Mexico: Institutions and forests in a globalized countryside. Professional Geographer. 2003;55:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Krutilla K, Hyde WF, Barnes D. Periurban deforestation in developing-countries. Forest Ecology and Management. 1995;74:181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Lambin EF, Meyfroidt P. Land use transitions: Socio-ecological feedback versus socio-economic change. Land Use Policy. 2010;27:108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Laurance WF. The need to cut China’s illegal timber imports. Science. 2008;319:1184–1184. doi: 10.1126/science.319.5867.1184b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurance WF, Goosem M, Laurance SGW. Impacts of roads and linear clearings on tropical forests. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2009;24:659–669. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WJ. Environmental management indicators for ecotourism in China’s nature reserves: A case study in Tianmushan Nature Reserve. Tourism Management. 2004;25:559–564. [Google Scholar]

- Li WJ, Han NY. Ecotourism management in China’s nature reserves. Ambio. 2001;30:62–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lipovetsky S, Conklin M. Analysis of regression in game theory approach. Applied Stochastic Models in Business and Industry. 2001;17:319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Liu JG. China’s Road to Sustainability. Science. 2010;328:50–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1186234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JG, Daily GC, Ehrlich PR, Luck GW. Effects of household dynamics on resource consumption and biodiversity. Nature. 2003;421:530–533. doi: 10.1038/nature01359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JG, Diamond J. China’s environment in a globalizing world. Nature. 2005;435:1179–1186. doi: 10.1038/4351179a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JG, Li SX, Ouyang ZY, Tam C, Chen XD. Ecological and socioeconomic effects of China’s policies for ecosystem services. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:9477–9482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706436105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JG, Raven PH. China’s environmental challenges and implications for the World. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 2010;40:823–851. [Google Scholar]

- Loucks CJ, Zhi L, Dinerstein E, Wang D, Fu D, Wang H. The giant pandas of the Qinling Mountains, China: a case study in designing conservation landscapes for elevational migrants. Conservation Biology. 2003;17:558–565. [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Zheng J. Ecotourism in nature reserves in China: current situation, problems and solutions. Forestry Studies in China. 2008;10:130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Mather AS. The forest transition. Area. 1992;24:367–379. [Google Scholar]

- Mather AS. Forest transition theory and the reforesting of Scotland. Scottish Geographical Journal. 2004;120:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Mather AS. Recent Asian forest transitions in relation to forest-transition theory. International Forestry Review. 2007;9:491–502. [Google Scholar]

- Mather AS, Fairbairn J. From floods to reforestation: the forest transition in Switzerland. Environment and History. 2000;6:399–421. [Google Scholar]

- Mather AS, Fairbairn J, Needle CL. The course and drivers of the forest transition: the case of France. Journal of Rural Studies. 1999;15:65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mather AS, Needle CL. The forest transition: a theoretical basis. Area. 1998;30:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Mather AS, Needle CL, Coull JR. From resource crisis to sustainability: the forest transition in Denmark. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology. 1998;5:182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens B, Sunderlin WD, Ndoye O, Lambin EF. Impact of macroeconomic change on deforestation in South Cameroon: Integration of household survey and remotely-sensed data. World Development. 2000;28:983–999. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer WB, Turner BL. Human-population growth and global land-use cover change. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1992;23:39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Meyfroidt P, Lambin EF. Forest transition in Vietnam and displacement of deforestation abroad. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:16139–16144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904942106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikesell MW. Deforestation in northern. Morocco Science. 1960;132:441–448. doi: 10.1126/science.132.3425.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne S, Niesten E. Direct payments for biodiversity conservation in developing countries: practical insights for design and implementation. Oryx. 2009;43:530–541. [Google Scholar]

- Myers N. The world’s forests and human populations: The environmental interconnections. Population and Development Review. 1990;16:237–251. [Google Scholar]

- Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. NATURE. 2000;403:853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagendra H. Drivers of reforestation in human-dominated forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:15218–15223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702319104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagendra H, Karmacharya M, Karna B. Evaluating forest management in Nepal: Views across space and time. Ecology and Society. 2005:10. [Google Scholar]

- Nagendra H, Southworth J, Tucker C. Accessibility as a determinant of landscape transformation in western Honduras: linking pattern and process. Landscape Ecology. 2003;18:141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Nepstad D, Carvalho G, Barros AC, Alencar A, Capobianco JP, Bishop J, Moutinho P, Lefebvre P, Silva UL, Prins E. Road paving, fire regime feedbacks, and the future of Amazon forests. Forest Ecology and Management. 2001;154:395–407. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity. 2007;41:673–690. [Google Scholar]

- Olson DM, Dinerstein E, Wikramanayake ED, Burgess ND, Powell GVN, Underwood EC, D’Amico JA, Itoua I, Strand HE, Morrison JC, Loucks CJ, Allnutt TF, Ricketts TH, Kura Y, Lamoreux JF, Wettengel WW, Hedao P, Kassem KR. Terrestrial ecoregions of the worlds: A new map of life on Earth. Bioscience. 2001;51:933–938. [Google Scholar]

- Ott RL, Longnecker M. An introduction to statistical methods and data analysis (Fifth Edition) Duxbury; Pacific Grove: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ou H, Wu C, Gao H. A study aiming at working out the standard and methodology of mapping in the comprehensive land use plannning at village and town level. Journal of Zhejiang University. 2002;28:4. [Google Scholar]

- Pahari K, Murai S. Modelling for prediction of global deforestation based on the growth of human population. Isprs Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. 1999;54:317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Pan WKY, Bilsborrow RE. The use of a multilevel statistical model to analyze factors influencing land use: a study of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Global and Planetary Change. 2005;47:232–252. [Google Scholar]

- Pan WS, Gao ZS, Lv Z. The giant panda’s natural refuge in the Qinling Mountains (in Chinese) Peking University Press; Beijing: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Cheng G, Xu Z, Yin Y, Xu W. Social, economic, and ecological impacts of the “Grain for Green” project in China: A preliminary case in Zhangye, Northwest China. Journal of Environmental Management. 2007;85:774–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perz SG. Grand theory and context-specificity in the study of forest dynamics: Forest transition theory and other directions. Professional Geographer. 2007;59:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Perz SG, Skole DL. Secondary forest expansion in the Brazilian Amazon and the refinement of forest transition theory. Society & Natural Resources. 2003;16:277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff A, Robalino J, Walker R, Aldrich S, Caldas M, Reis E, Perz S, Bohrer C, Arima E, Laurance W, Kirby K. Roads and deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Journal of Regional Science. 2007;47:109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff ASP. What drives deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon? Evidence from satellite and socioeconomic data. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management. 1999;37:26–43. [Google Scholar]

- Prunty M. Recent expansions in the southern pulp-paper industries Economic Geography 32:51–57 1956 [Google Scholar]

- Qin H. Rural-to-Urban Labor Migration, Household Livelihoods, and the Rural Environment in Chongqing Municipality, Southwest China. Human Ecology. 2010;38:675–690. doi: 10.1007/s10745-010-9353-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabus B, Eineder M, Roth A, Bamler R. The shuttle radar topography mission - a new class of digital elevation models acquired by spaceborne radar. Isprs Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. 2003;57:241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ran YH, Li X, Lu L. Evaluation of four remote sensing based land cover products over China. International Journal of Remote Sensing. 2010;31:391–401. [Google Scholar]

- Royer JP. Determinants of reforestation behavior among southern landowners. Forest Science. 1987;33:654–667. [Google Scholar]

- Rudel TK. Is there a forest transition? Deforestation, reforestation, and development. Rural Sociology. 1998;63:533–552. [Google Scholar]

- Rudel TK. Tropical Forests. Columbia University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rudel TK, Coomes OT, Moran E, Achard F, Angelsen A, Xu JC, Lambin E. Forest transitions: towards a global understanding of land use change. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions. 2005;15:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rudel TK, Schneider L, Uriarte M. Forest transitions: An introduction. Land Use Policy. 2010;27:95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rush J. The last tree: reclaiming the environment in tropical Asia. The Asia Society; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sedjo RA, Clawson M. How serious is tropical deforestation. Journal of Forestry. 1983;81:792–794. [Google Scholar]

- Shen YQ, Liao XC, Yin RS. Measuring the socioeconomic impacts of China’s Natural Forest Protection Program. Environment and Development Economics. 2006;11:769–788. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan Provincial People’s Government. Government Document. 2006. Suggestion for accelerating rural road networks in Sichuan Province (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Soares B, Alencar A, Nepstad D, Cerqueira G, Diaz MDV, Rivero S, Solorzano L, Voll E. Simulating the response of land-cover changes to road paving and governance along a major Amazon highway: the Santarem-Cuiaba corridor. Global Change Biology. 2004;10:745–764. [Google Scholar]

- Southgate D, Sierra R, Brown L. The causes of tropical deforestation in Ecuador - A statistical – analysis. World Development. 1991;19:1145–1151. [Google Scholar]

- State Forestry Administration. The 3rd national survey report on giant panda in China (in Chinese) Science Press; Beijing: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- State Forestry Administration. Review for 10-year implementation of Natural Forest Conservation Program in China (in Chinese) 2009a http://www.forestry.gov.cn/ZhuantiAction.do?dispatch=content&id=266161&name=ly60.

- State Forestry Administration. WWF will cooperate with Wolong Nature Reserve in constructing beautiful new Wolong (in Chinese) 2009b http://www.forestry.gov.cn/portal/main/s/438/content-32548.html.

- State Forestry Administration. Government Report. 2010a. 2009 forest development report of China (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- State Forestry Administration. Results of the 7th national forest resouces survey (in Chinese) 2010b http://www.forestry.gov.cn/portal/main/s/65/content-326341.html.

- Totman C. Plantation forestry in early-modern Japan - economic - aspects of its emergence. Agricultural History. 1986;60:23–51. [Google Scholar]

- Trac CJ, Harrell S, Hinckley TM, Henck AC. Reforestation programs in southwest China: Reported success, observed failure, and the reasons why. Journal of Mountain Science. 2007;4:275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Turner BL, Moss RH, Skole DL. Relating land use and global land-cover change: A proposal for an IGBP-HDP core project. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. office of the Environmental Investigation Agency. No questions asked-the impacts of U.S. market demand for illeagal timber-and the potential for change. Report 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Uchida E, Rozelle S, Xu JT. Conservation payments, liquidity constraints, and off-farm labor: impact of the Grain-for-Green Program on rural households in China. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2009;91:70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Uchida E, Xu JT, Xu ZG, Rozelle S. Are the poor benefiting from China’s land conservation program? Environment and Development Economics. 2007;12:593–620. [Google Scholar]

- Viña A, Chen XD, McConnell WJ, Liu W, Xu WH, Ouyang ZY, Zhang HM, Liu JG. Effects of Natural Disasters on Conservation Policies: The Case of the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake, China. Ambio. 2011;40:274–284. doi: 10.1007/s13280-010-0098-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters BB. Human ecological questions for tropical restoration: experiences from planting native upland trees and mangroves in the Philippines. Forest Ecology and Management. 1997;99:275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Wen Y, Yang L. Economic dependence of communities surrounding the giant panda nature reserve on natural resources in the Qinling Mountains: a case study on the Foping Nature Reserve (in Chinese) Resources Science. 2010;32:8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang GY, Innes JL, Lei JF, Dai SY, Wu SW. Ecology - China’s forestry reforms. Science. 2007;318:1556–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1147247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannitikul G. Deforestation in northeast Thailand, 1975–91: Results of a general statistical model. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography. 2005;26:102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Weyerhaeuser H, Wilkes A, Kahrl F. Local impacts and responses to regional forest conservation and rehabilitation programs in China’s northwest Yunnan province. Agricultural Systems. 2005;85:234–253. [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. Deforestation-past and present. Progress in Human Geography. 1989;13:176–208. [Google Scholar]

- World Wildlife Fund. Report suggests China’s ‘Grain-to-Green’ plan is fundamental to managing water and soil erosion. 2003 http://www.wwfchina.org/english/loca.php?loca=159.

- World Wildlife Fund. Ecological conservation and sustainable socioeconomic development projects in the Qinling Mountains (in Chinese) 2004 http://www.wwfchina.org/aboutwwf/whatwedo/species/qinling.shtm.

- Wu W, Shibasaki R, Yang P, Ongaro L, Zhou Q, Tang H. Validation and comparison of 1 km global land cover products in China. International Journal of Remote Sensing. 2008;29:3769–3785. [Google Scholar]

- Xu JT, Tao R, Xu ZG. Sloping land conversion program: cost-effectiveness, structural effect and economic sustainability (in Chinese) China Economic Quarterly. 2004;4:24. [Google Scholar]

- Xu JY, Chen LD, Lu YH, Fu BJ. Sustainability evaluation of the grain for green project: From local people’s responses to ecological effectiveness in wolong nature reserve. Environmental Management. 2007;40:113–122. doi: 10.1007/s00267-006-0113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Qi Y, Gong P. China’s new forest policy. Science. 2000;289:2049–2049. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2049b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu WH, Ouyang Z, Vina A, Zheng H, Liu JG, Xiao Y. Designing a conservation plan for protecting the habitat for giant pandas in the Qionglai mountain range, China. Diversity and Distributions. 2006;12:610–619. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Li C, editors. Forest of Sichuan Province (in Chinese) China Forestry Express; Beijing: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ye YQ, Chen GJ, Hong F. Impacts of the “Grain for Green” project on rural communities in the Upper Min River Basin, Sichuan, China. Mountain Research and Development. 2003;23:345–352. [Google Scholar]

- Young KR. Roads and the envrionmental degradation of tropical Montane forests. Conservation Biology. 1994;8:972–976. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang PC, Shao GF, Zhao G, Le Master DC, Parker GR, Dunning JB, Li QL. Ecology - China’s forest policy for the 21st century. Science. 2000;288:2135–2136. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. Review of the Tenth Five-year Plan and view of the Eleventh Five-year Plan in Natural Forest Protection Program (in Chinese) Forestry Economics. 2006;1:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Yang Z, Zhu Y, Wang X. Tree species selection of Grain-to-Green Program in Northewestern China (in Chinese) Protection Forest Science and Technology. 2003;4:59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G, Shao GF, Zhang PC, Bai GX. China’s new forest policy - Response. Science. 2000;289:2049–2050. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Yin Y, Xu W, Ji Z, Caldwell I, Ren J. The costs and benefits of reforestation in Liping County, Guizhou province, China. Journal of Environmental Management. 2007;85:722–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CQ, Feng GQ. Research for Grain to Green policy and case study of management in China (in Chinese) Science Press; Beijing: 2003. [Google Scholar]