Abstract

Objectives

The endothelial lipase gene (LIPG) is one of the important genes in the metabolism of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and may be involved in the pathogenesis of coronary artery disease (CAD).

Materials and methods

To investigate the relationship between the common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) 584C/T (rs2000813) and −384A/C (rs3813082) in the LIPG gene and CAD, allele and genotype frequencies of the two SNPs were analysed in 287 Chinese patients with CAD and 367 controls by the high-resolution melting curve (HRM) method.

Results

For 584C/T, no significant difference in polymorphic distribution was observed between patients and controls. However, the frequencies of allele C (20.2% vs 15%, p=0.013, OR=1.437, 95% CI 1.078 to 1.915) at −384A/C were significantly increased in patients compared with controls. Haplotype analysis also showed that haplotype CT (12.37% vs 8.72%, p=0.035, OR=1.478, 95% CI 1.034 to 2.112) was significantly higher in patients compared with controls.

Conclusions

These results suggested that the SNP −384A/C in the LIPG gene may be associated with risk for CAD and the LIPG gene may play a role in CAD in the Han Chinese.

Keywords: Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), Endothelial lipase gene (LIPG), Association

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The results suggested that the −384A/C variation in LIPG gene may be a genetic risk factor for coronary artery disease (CAD).

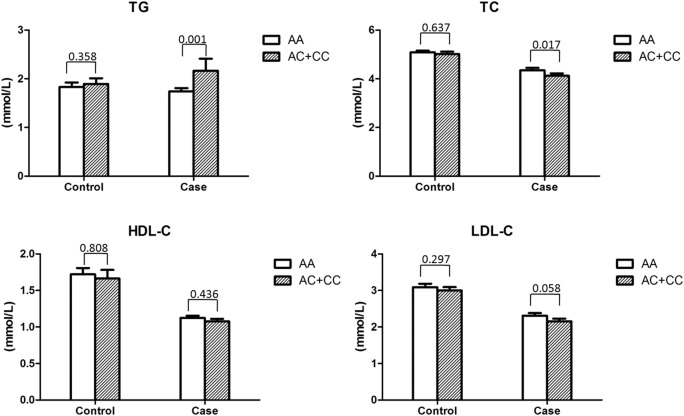

There were significant changes of the triglyceride (TG) level and the total cholesterol (TC) level in the male patients with C allele of SNP −384A/C compared with those in the male control individuals.

The population size is limited and future studies with larger population sizes are needed to test our results.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is one of the major causes of death around the world. It is well known that as a complex disease, CAD is due to both environmental and genetic aetiological determinants. Previous studies suggested that decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and raised triglyceride (TG) levels are well-known risk factors for the pathogenesis of the disease.1 It is generally accepted that HDL-C levels are inversely associated with risk of CAD.2 At least 80% of the blood level of HDL-C levels in humans is genetically determined. Therefore, the researchers are interested in the variations of the genes responsible for regulating the HDL metabolism, such as hepatic lipase (LIPC), lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT), cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), and phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) genes. Over the past few years, the genetic variations have been systematically explored in some ethic groups (reviewed in3).

As a new member of the triglyceride (TG) lipase gene family, the endothelial lipase (EL), synthesised by endothelial cell and expressing in a variety of tissues including the coronary arteries, liver, lung, kidney, ovary, thyroid gland, testis and placenta, has been identified.4 EL shares a 45%, 40% and 27% homologous amino acid sequence with lipoprotein lipase (LPL), hepatic lipase (HL) and pancreatic lipase (PL), respectively. It keeps many characteristic features of LPL and HL such as catalytic triad, heparin-binding sites, lipid-binding regions and cysteine residues necessary for enzyme activity. In contrast to LPL and HL, EL shows substantial phospholipase activity and less triglyceride lipase activity. However, EL prefers to catalyse the phospholipids within HDL and plays an important role in the regulation of plasma HDL-C levels.4

The endothelial lipase gene (LIPG) was cloned and characterised in 1999 by two independently different groups. It is located on chromosome 18q12.1–q12.3, spans about 30 kb with 10 exons and encodes a polypeptide of 500 amino acids. Experimentally, overexpression of the gene can reduce plasma concentrations of HDL-C5–7 and its inhibition results in increased HDL-C level.8 9 Also, previous studies showed that EL was a negative regulator of HDL-C in vivo.8 10 11 These data suggested that LIPG played an important role in HDL-C metabolism and may be a putative new target for prevention and treatment of CAD. Thus, exploring the associations between genetic polymorphisms in the LIPG gene and CAD is important. There were several studies focusing on the common variations in the LIPG gene.12–15 Among the common variations, −384A>C (rs3813082) in the promoter region has been associated with acute coronary syndrome in the Han and Uygur Chinese populations.16 17 Meanwhile, another single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) 584C>T (rs2000813) in exon 3 was suggested as a protective effector of CAD in Han Chinese people,13 which was challenged by a recent meta-analysis.18 As the results were contrary in the present study, the frequencies of −384A>C (rs3813082) and 584C>T (rs2000813) were investigated in patients with CAD and compared with those in controls in order to explore the possible association between the two SNPs and CAD in a Han Chinese population.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Two hundred eighty-seven unrelated patients with CAD were recruited from the West China Hospital, Sichuan University. The diagnosis was confirmed by coronary angiography using the Judkins technique. An individual having at least one stenosis >60% in any of the major branches of a coronary artery (left anterior descending, left circumflex and right coronary artery) was qualified as a ‘CAD patient’. None of the patients took hypolipidemic drugs prior to the angiography and lipid measurement. In addition, 367 unrelated persons, free of any clinical or biochemical signs of CAD, were selected via health examinations at the same hospital as controls. Informed consents were obtained from all the persons in this study.

Measurement of lipids and lipoproteins

Blood samples were collected at baseline from patients and controls after an overnight fast. Plasma was separated from cells and used immediately for lipid and lipoprotein analyses. The levels of plasma total cholesterol (TC), TG, HDL-C and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) were determined by an automated chemistry analyzer (Olympus AU5400, Japan) with an enzymatic kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany).

DNA preparation, PCR amplification and genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from leucocytes of peripheral blood samples using a DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany). Primers were designed with Primer3 and synthesised by Invitrogen (Life Technologies, USA). Primer sequences were shown in table 1. Polymorphisms of the two SNPs were detected by the high-resolution melting curve (HRM) method. PCR amplifications and HRM procedures were performed in 96-well plates in the LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Bavaria, Germany).

Table 1.

Primer sequences for genotyping polymorphisms.

| Polymorphism | Gene | Reference SNP ID | Ref SNP Alleles | Primer sequences | Product lengh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −384 | LIPG | rs3813082 | A/C | F: 5′-CCCAGGGAGCGGATAGACCAC-3′ R: 5′-AGTGGCGGAGGCGGACATTTC-3′ |

127 bp |

| 584 | LIPG | rs2000813 | C/T | F: 5′-GAGCGGTATCTTTGAAAACTGG-3′ R: 5′-TATTATTGACCGCATCCGTGT-3′ |

131 bp |

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphisms.

The PCR reaction (10 μL) contained 20 ng of genomic DNA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 μΜ of each primer (forward and reverse), respectively and 2×of the LightCycler480 High Resolution Melting Master Mix (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA). PCR amplification was carried out as the following procedure: initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, amplification for 45 cycles including denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, annealing at 60°C (62°C for 584C/A) for 15 s and extension at 72°C for 25 s. After amplification was finished, a high-resolution melting curve analysis protocol was performed for the PCR products following the procedure: first, denaturing at 95°C for 1 min and cooling to 40°C for 1 min; second, gradually increasing the temperature from 65°C to 95°C at a rate of 0.01°C/s; finally, the instrument cooled down to 40°C. After PCR amplification and melting curve analysis, data were analysed by the LightCycler 480 Gene Scanning software V.2.0 (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). DNA samples with known genotypes were used as reference samples for HRM analysis of the two polymorphisms. For each SNP, three reference DNA samples were added in each run.

Portions of PCR products were selected and sequenced for the verification of melting curve results. Sequencing primers were the same primers used in the PCRs. Nucleotide sequencing was performed by the BigDye Terminator V.3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and ABI 3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analysis

The allele and genotype frequencies were determined by counting. The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was tested with HWE software.19 The differences in genotypic and allelic distribution between patients and controls were evaluated by χ2 or Fisher's exact tests (when appropriate). Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the OR for CAD after adjusting for other factors. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between the SNPs was assessed using the 2LD program (http://www.iop.kcl.ac.uk/iop/Departments/PsychMed/GEpiBSt/software.shtml). The haplotype frequencies were estimated by PHASE software20 21 (http://www.stat.washington.edu/stephens/software.html). Relative risk was presented as ORs. The distribution of continuous variables was expressed as mean±SD. The lipid phenotypic data of patients and controls were compared by Student t test.

Results

The clinical data of the patients with CAD are listed in table 2. The demographics and lipid profiles of the patients and controls with CAD are listed in table 3. The levels of TC, HDL-C and LDL-C were significantly lower in the patients with CAD than in the controls, without statistically significant differences between males and females.

Table 2.

Clinical data of patients with CAD

| N | Gender (M/F) | Diabetes (%) | Hypertension (%) | Family history (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 287 | 204/83 | 18.12 | 53.66 | 8.71 |

CAD, coronary artery disease.

Table 3.

Demographics and lipid profiles of patients and controls with CAD

| Trait* | CAD |

Control |

p Value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=204) | Female (n=83) | Male (n=233) | Female (n=134) | M vs M | F vs F | |

| Age | 59.88±9.20 | 61.01±8.33 | 61.26±8.93 | 58.69±8.54 | NS | 0.05 |

| BMI | 24.6±1.25 | 23.7±1.13 | 24.4±1.22 | 23.4±1.11 | NS | NS |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.90±1.51 | 2.17±1.43 | 1.85±1.13 | 1.95±1.19 | NS | NS |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.26±1.03 | 4.61±1.06 | 5.07±0.85 | 5.21±0.85 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.11±0.32 | 1.21±0.28 | 1.70±1.08 | 1.62±0.48 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.25±0.78 | 2.32±0.81 | 3.06±1.11 | 3.17±0.81 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

*All levels are given in mmol/L except body mass index (BMI) which is given in kg/m2 and age given in years.

NS, no significant difference (p>0.05).

BMI, body mass index, HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDC-C; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NS, not significant; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

Table 4 showed the genotypic and allelic frequencies of polymorphisms −384A/C and 584C/T in the LIPG gene in the patients and controls with CAD. The distributions of genotypes of the two SNPs were in the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the CAD and control groups (data not shown).

Table 4.

Genotypic and allelic frequency distribution of −384A/C and 584C/T polymorphic of the LIPG gene in patients and controls with CAD

| CAD n=287 |

Control n=367 |

p Value* | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIPG −384A/C (rs3813082) | |||||

| Genotype frequency | AA | 184 (64.1%) | 267 (72.8%) | Reference | |

| AC | 90 (31.4%) | 90 (24.5%) | |||

| CC | 13 (4.5%) | 10 (2.7%) | 0.051 | ||

| AC+CC | 103 (35.9%) | 100 (27.2%) | 0.018 | 1.495 (1.071 to 2.085) | |

| 0.071† | 1.524 (0.964 to 2.410)† | ||||

| Allele frequency | A | 458 (79.8%) | 624 (85.0%) | Reference | |

| C | 116 (20.2%) | 110 (15.0%) | 0.013 | 1.437 (1.078 to 1.915) | |

| LIPG 584C/T (rs2000813) | |||||

| Genotype frequency | CC | 160 (55.7%) | 216 (58.9%) | Reference | |

| CT | 116 (40.4%) | 139 (37.9%) | |||

| TT | 11 (3.8%) | 12 (3.3%) | 0.711 | ||

| CT+TT | 127 (44.3%) | 151 (41.1%) | 0.427 | 1.135 (0.831 to 1.552) | |

| Allele frequency | C | 436 (76.0%) | 571 (77.8%) | Reference | |

| T | 138 (24.0%) | 163 (22.2%) | 0.467 | 1.109 (0.856 to 1.436) | |

*Compared with controls.

†Adjusted by age, gender, TC, TG, HDL-C and LDL-C.

HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDC-C; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

As shown in tables 4, at −384A/C locus the frequency of C allele carriers (AC+CC) was significantly higher in CAD patients than that in controls (35.9% vs 27.2%, p=0.018, OR=1.495, 95% CI 1.071 to 2.085). However, when adjusted by age, gender, TC, TG, HDL-C and LDL-C, the difference in the frequencies of C allele carriers between patients and controls was no longer significant (p=0.071, OR=1.524, 95% CI 0.964 to 2.410).

At the 584C/T locus, no significant differences in genotype or allele frequencies between patients and controls were observed. After stratification by gender, significant differences in frequencies of C allele carriers (AC+CC) between patients and controls at −384A/C still existed between patients and controls in males (tables 5 and 6, 38.7% vs 29.6%, p=0.045, OR=1.502, 95% CI 1.009 to 2.237). However, when adjusted by age, gender, TC, TG, HDL-C and LDL-C, the significance disappeared (p=0.180, OR=1.425, 95% CI 0.849 to 2.390).

Table 5.

Genotypic and allelic frequency distribution of −384A/C and 584C/T polymorphic of the LIPG gene in male patients and male controls with CAD

| CAD n=204 |

Control n=233 |

p Value* | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −384A/C | |||||

| Genotype frequency | AA | 125 (61.3%) | 164 (70.4%) | Reference | |

| AC | 71 (34.8%) | 61 (26.2%) | |||

| CC | 8 (3.9%) | 8 (3.4%) | 0.128 | ||

| AC+CC | 79 (38.7%) | 69 (29.6%) | 0.045 | 1.502 (1.009 to 2.237) | |

| 0.180† | 1.425(0.849 to 2.390)† | ||||

| Allele frequency | A | 321 (78.7%) | 389 (83.5%) | Reference | |

| C | 87 (21.3%) | 77 (16.5%) | 0.070 | 1.369 (0.974 to 1.924) | |

| 584C/T | |||||

| Genotype frequency | CC | 114 (55.9%) | 127 (54.5%) | Reference | |

| CT | 79 (38.7%) | 98 (42.1%) | |||

| TT | 11 (5.4%) | 8 (3.4%) | 0.523 | ||

| CT+TT | 90 (44.1%) | 106 (45.5%) | 0.773 | 0.946 (0.648 to 1.380) | |

| Allele frequency | C | 307 (75.2%) | 352 (75.5%) | Reference | |

| T | 101 (24.8%) | 114 (24.5%) | 0.921 | 1.016 (0.746 to 1.383) | |

*Compared with controls.

†Adjusted by age, gender, TC, TG, HDL-C and LDL-C.

CAD, coronary artery disease; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LIPG, endothelial lipase gene; LDC-C; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

Table 6.

Genotypic and allelic frequency distribution of −384A/C and 584C/T Polymorphic of LIPG gene in female patients and female controls with CAD

| CAD n=83 |

Control n=134 |

p Value* | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −384A/C | |||||

| Genotype frequency | AA | 59 (71.1%) | 103 (76.9%) | Reference | |

| AC | 19 (22.9%) | 29 (21.6%) | |||

| CC | 5 (6.0%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0.184 | ||

| AC+CC | 24 (28.9%) | 31 (23.1%) | 0.341 | 1.352 (0.726 to 2.516) | |

| Allele frequency | A | 137 (82.5%) | 235 (87.7%) | Reference | |

| C | 29 (17.5%) | 33 (12.3%) | 0.136 | 1.507 (0.877 to 2.591) | |

| 584C/T | |||||

| Genotype frequency | CC | 46 (55.4%) | 89 (66.4%) | Reference | |

| CT | 37 (44.6%) | 41 (30.6%) | |||

| TT | 0 | 4 (3.0%) | 0.043 | ||

| CT+TT | 37 (44.6%) | 45 (33.6%) | 0.104 | 1.591 (0.907 to 2.791) | |

| Allele frequency | C | 129 (77.7%) | 219 (81.7%) | Reference | |

| T | 37 (22.3%) | 49 (18.3%) | 0.309 | 1.282 (0.794 to 2.070) | |

*Compared with controls.

CAD, coronary artery disease; LIPG, endothelial lipase gene.

We analysed the lipid profile according to the −384A/C genotypes in patients and control individuals with CAD. There were no significant differences in the TG, TC, HDL-C and LDL-C levels between the AA group and the AC+CC group in patients and controls, respectively. However, when stratified by gender, a significant increase in the TG level (p=0.001) and a significant decrease in the TC level (p=0.017) were detected in the AC+CC group compared with the AA group in male patients with CAD, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The lipid profile according to −384A/C genotypes in patients and control individuals with CAD.

Since a moderate linkage disequilibrium was observed between −384A/C and 584C/T polymorphisms in controls (D′=0.3349), we used the PHASE case–control test for detecting the association between haplotypes of the two SNP loci and patients with CAD. As a result, haplotype CT (12.37% vs 8.72%, p=0.035, OR=1.478, 95% CI 1.034 to 2.112) significantly increased in patients with CAD compared with controls (shown in table 7).

Table 7.

LIPG haplotype frequencies in patients and controls with CAD

| Group | Number of case | Haplotype frequency (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | AT | CC | CT | ||

| CAD | 287 | 68.12 (391/574) | 7.84 (45/574) | 11.67 (67/574) | 12.37 (71/574) |

| Control | 367 | 71.53 (525/734) | 6.27 (46/734) | 13.49 (99/734) | 8.72 (64/734) |

| p Value* | NS | NS | NS | 0.035 | |

| OR | 1.478 | ||||

| 95% CI | 1.034 to 2.112 | ||||

*Compared with controls.

CAD, coronary artery disease; LIPG, endothelial lipase gene.

Discussion

The HDL metabolism is complicated and contributes to the aetiology of CAD; therefore, the genes involved in HDL metabolism are probably potential targets for the prevention and treatment of CAD. Also, a previous study suggested that the 40–60% susceptibility of CAD was inherited,22 and by now there have been 50 genetic risk variations found to be associated with CAD with genome-wide significances.23 Some variations are located near the genes participating in LDL and HDL metabolism, such as LPA, APOE and ANKS1A. Therefore, it is necessary to quest the association between the genetic variations in the newly discovered gene LIPG and CAD. However, the results of previous studies on the genetic contribution of the LIPG gene polymorphism were inconsistent.12–15 In our study, two polymorphisms, −384A/C in the promoter and 584C/T in exon 3, were selected and analysed. The reason for the selection is the important role of the promoter in gene transcription and the potential effects of non-synonymous mutations on gene functions. Furthermore, the 584C/T is a common SNP across the different ethnic population and it is important to examine the distribution of this SNP in different ethnic groups.

At the −384A/C polymorphism in LIPG, frequencies of allele C and carriers with allele C in patients with CAD were significantly higher than those in controls, suggesting that there was an association between the polymorphism and CAD, and the C allele may increase the susceptibility to CAD. However, when adjusted by other factors, the frequencies of carriers with allele C between the case and control groups were no longer significant (p=0.071). The reason could be the limited population size in this study and the relative low amounts of individuals with CC genotype (13 and 10, respectively). The limited population size might reduce the effects of genetic factors, especially when adjusted by other factors. The results is consistent with previous studies which associated this SNP with acute coronary syndrome in the Han and Uygur Chinese populations.16 17 Since the polymorphism was located in the promoter region, we evaluated its possible effect on transcription by searching the TRANSFAC database 6.0. We found that −384A/C was located in one of the binding motifs of transcriptional factor LF-A1, which played an important role in the transcription of apolipoproteins Al, A2, B1 and A4 in the liver.24 Since the A to C change of the polymorphism could lead to the loss of the binding motif of LF-A1, the −384A/C variation could affect the transcription of LIPG. This is a possible reason why the polymorphism increases the risk for CAD. After stratifying the participants by gender, the association of the frequency of allele C with CAD remained to be observed in males, but not in females, which suggested that the influence of the −384A/C variation on the risk for CAD may be different between men and women. However, when we analysed the concentration of lipoproteins stratified by genotype, we only detected a significant increase in TG and a significant decrease in TC in the AC/CC genotype group compared to the AA genotype group, with no effect on the HDL-C levels. As EL belongs to the TG lipase gene family and its preferred substrate is HDL-C, the results here suggested other potential pathways that EL could take part in.

As to 584C/T, no significant difference in polymorphic distribution was observed between patients and controls, indicating that the SNP was not associated with CAD. The result is consistent with a recent meta-analysis.18 Also, the association between the SNP and the level of HDL-C was not detected in patients and controls in this study. In 2003, Ma et al.25 found an association between this SNP with HDL-C and other lipid parameters in a cohort consisting of 372 individuals with normal cholesterol levels, but the association was weak and no significant associations between this SNP and progression or regression of coronary lesions were observed in this prospective study. The results given by Mank-Seymour et al26 also came from a prospective study. However, recent results suggested no association between 584C/T and HDL-C.14 The apparent discrepancy was most likely the result of different study designs. Since the studies above were performed in health populations, it is important to investigate the association between the SNP and cardiovascular disease. The results from our study suggest that there is no effect of 584C/T on metabolism of HDL in Han Chinese people.

Since the linkage disequilibrium of −384A/C and 584C/T is not very strong, we performed further haplotype analysis for the two SNPs in both patients and controls with CAD. The results showed that the frequency of haplotype CT significantly increased in patients, compared with controls, suggesting that haplotype CT could be a risk factor for patients with CAD, which provided the evidence again that variation of LIPG may be involved in susceptibility to CAD.

Although the results suggested an association between the SNP −384A/C in LIPG and CAD in a Han Chinese population, there are still several limitations. First, the population size in this study is limited. A total of 287 patients with CAD and 367 control individuals were recruited in the study. Second, the disease phenotype was not divided into subcategories. As the exact functions of the lipid metabolism in the pathogenesis of various CAD are unclear, we decided to combine all categories of CAD and got a positive result. Third, LIPG belongs to the TG lipase gene family and its preferred substrate is HDL-C; however, the SNP −384A/C was not associated with the HDL-C level in this study. The reason may lie in the compensation of other lipases. Additionally, the significant differences in TG and TC in different genotype groups suggest other potential ways in which LIPG attends to lipid metabolism.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first case–control study on the association of the SNP −384A/C of LIPG with CAD in a Han Chinese population. Our results suggested that the −384A/C variation in LIPG may be a genetic risk factor for CAD and further functional analysis to elucidate the role of LIPG in CAD is needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by ‘The Grants from Ministry of Education of China’(313037), Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University ‘PCSIRT’ (IRT0935), Research Project from Health Department of Sichuan Province (130114) and Nature Science Foundation of China (81401238).

Footnotes

Contributors: LX, YS and YD conceived and designed the experiments. LX, YS and YD performed the experiments. LX, YL, YT and YD analysed the data. LX, YS and YD wrote the paper.

Funding: This study was funded by The Grants from Ministry of Education of China (313037), Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University ‘PCSIRT’ (IRT0935), Research Project from Health Department of Sichuan Province (130114) and Nature Science Foundation of China (81401238).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV et al. . Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 2010;466:707–13. 10.1038/nature09270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon DJ, Rifkind BM. High-density lipoprotein—the clinical implications of recent studies. N Engl J Med 1989;321:1311–16. 10.1056/NEJM198911093211907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts R, Stewart AF. The genetics of coronary artery disease. Curr Opin Cardiol 2012;27:221–7. 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3283515b4b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yasuda T, Ishida T, Rader DJ. Update on the role of endothelial lipase in high-density lipoprotein metabolism, reverse cholesterol transport, and atherosclerosis. Circ J 2010;74:2263–70. 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirata K, Dichek HL, Cioffi JA et al. . Cloning of a unique lipase from endothelial cells extends the lipase gene family. J Biol Chem 1999;274:14170–5. 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaye M, Lynch KJ, Krawiec J et al. . A novel endothelial-derived lipase that modulates hdl metabolism. Nat Genet 1999;21:424–8. 10.1038/7766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maugeais C, Tietge UJ, Broedl UC et al. . Dose-dependent acceleration of high-density lipoprotein catabolism by endothelial lipase. Circulation 2003;108:2121–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000092889.24713.DC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edmondson AC, Brown RJ, Kathiresan S et al. . Loss-of-function variants in endothelial lipase are a cause of elevated HDL cholesterol in humans. J Clin Invest 2009;119:1042–50. 10.1172/JCI37176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown RJ, Lagor WR, Sankaranaravanan S et al. . Impact of combined deficiency of hepatic lipase and endothelial lipase on the metabolism of both high-density lipoproteins and apolipoprotein b-containing lipoproteins. Circ Res 2010;107:357–64. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.219188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badellino KO, Wolfe ML, Reilly MP et al. . Endothelial lipase concentrations are increased in metabolic syndrome and associated with coronary atherosclerosis. PLoS Med 2006;3:e22 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown RJ, Edmondson AC, Griffon N et al. . A naturally occurring variant of endothelial lipase associated with elevated hdl exhibits impaired synthesis. J Lipid Res 2009;50:1910–16. 10.1194/jlr.P900020-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu M, Kanazawa K, Hirata K et al. . Endothelial lipase gene polymorphism is associated with acute myocardial infarction, independently of high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels. Circ J 2007;71:842–6. 10.1253/circj.71.842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang NP, Wang LS, Yang L et al. . Protective effect of an endothelial lipase gene variant on coronary artery disease in a Chinese population. J Lipid Res 2008;49:369–75. 10.1194/jlr.M700399-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen MK, Rimm EB, Mukamal KJ et al. . The t111i variant in the endothelial lipase gene and risk of coronary heart disease in three independent populations. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1584–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vergeer M, Cohn DM, Boekholdt SM et al. . Lack of association between common genetic variation in endothelial lipase (LIPG) and the risk for CAD and DVT. Atherosclerosis 2010;211: 558–64. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai G, He G, Qi C. The association between endothelial lipase -384A/C gene polymorphism and acute coronary syndrome in a Chinese population. Mol Biol Rep 2012;39:9879–84. 10.1007/s11033-012-1854-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang D, Xie X, Ma YT et al. . Endothelial lipase-384A/C polymorphism is associated with acute coronary syndrome and lipid status in elderly Uygur patients in Xinjiang. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2014;18:781–4. 10.1089/gtmb.2014.0195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai G, Huang Z, Zhang B et al. . The associations between endothelial lipase 584C/T polymorphism and HDL-C level and coronary heart disease susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis 2014;13:85 10.1186/1476-511X-13-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terwilliger JD, Ott J. Handbook of human genetic linkage. Baltimore; Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994; p x, 307 p. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am J Hum Genet 2001;68:978–89. 10.1086/319501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephens M, Donnelly P. A comparison of Bayesian methods for haplotype reconstruction from population genotype data. Am J Hum Genet 2003;73:1162–9. 10.1086/379378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan L, Boerwinkle E. Gene-environment interactions and gene therapy in atherosclerosis. Cardiology in Review 1994;2:130–7. 10.1097/00045415-199405000-00003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts R. Genetics of coronary artery disease. Circ Res 2014;114;1890–903. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramji DP, Tadros MH, Hardon EM et al. . The transcription factor lf-a1 interacts with a bipartite recognition sequence in the promoter regions of several liver-specific genes. Nucleic Acids Res 1991;19:1139–46. 10.1093/nar/19.5.1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma K, Cilingiroglu M, Otvos JD et al. . Endothelial lipase is a major genetic determinant for high-density lipoprotein concentration, structure, and metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:2748–53. 10.1073/pnas.0438039100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mank-Seymour AR, Durham KL, Thompson JF et al. . Association between single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the endothelial lipase (lipg) gene and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004;1636:40–6. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2003.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]