Abstract

Objectives

In its guidelines on the use of portable monitors to diagnose obstructive sleep apnoea, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine endorses home polygraphy with type III devices recording at a minimum airflow the respiratory effort and pulse oximetry, but advises against simple pulse oximetry. However, oximetry is widely available and simple to use in the home. This study was designed to compare the ability of the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) based on oximetry alone with a stand-alone pulse oximeter (SPO) and from the oximetry channel of the ApneaLink Plus (ALP), with the respiratory disturbance index (RDI) based on four channels from the ALP to predict the apnoea–hypopnoea index (AHI) from laboratory polysomnography.

Design

Cross-sectional diagnostic accuracy study.

Setting

Sleep medicine practice of a multispecialty clinic.

Participants

Patients referred for laboratory polysomnography with suspected sleep apnoea. We enrolled 135 participants with 123 attempting the home sleep testing and 73 having at least 4 hours of satisfactory data from SPO and ALP.

Interventions

Participants had home testing performed simultaneously with both a SPO and an ALP. The 2 oximeter probes were worn on different fingers of the same hand. The ODI for the SPO was calculated using Profox software (ODISOX). For the ALP, RDI and ODI were calculated using both technician scoring (RDIMAN and ODIMAN) and the ALP computer scoring (RDIRAW and ODIRAW).

Results

The receiver–operator characteristic areas under the curve for AHI ≥5 were RDIMAN 0.88 (95% confidence limits 0.81–0.96), RDIRAW 0.86 (0.76–0.94), ODIMAN 0.86 (0.77–0.95), ODIRAW 0.84 (0.75–0.93) and ODISOX 0.83 (0.73–0.93).

Conclusions

We conclude that the RDI and the ODI, measured at home on the same night, give similar predictions of the laboratory AHI, measured on a different night. The differences between the two methods are small compared with the reported night-to-night variation of the AHI.

Keywords: SLEEP MEDICINE, sleep apnea, home testing

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study that directly compares the diagnostic accuracy of a type IV with a type III home testing system to predict the apnoea–hypopnoea index measured during laboratory polysomnography.

Limitations include the small number of participants, all covered by medical insurance, and the low number with significant comorbidity. Our results, therefore, may not be generalisable to all patients with suspected sleep apnoea, specifically those who are likely to have central sleep apnoea.

Another limitation was that 39% of the participants who attempted home testing had less than 4 h of valid recording on one or both of the home testing systems. However, the demographics of these participants were similar to those with successful tests.

Introduction

In the last decade, many home testing devices have been introduced to diagnose sleep apnoea with the goal of reducing the inconvenience and expense associated with laboratory polysomnography. Most of these record several channels in addition to pulse oximetry. However, simple pulse oximetry is a low-cost and widely available test and in some clinical settings it is still recommended to screen for sleep apnoea.1–6 A guideline from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine states that “at a minimum, [portable monitors] must record airflow, respiratory effort, and blood oxygenation”.7 This means that home testing must be performed with a type III device, now usually using 4–7 channels, rather than a type IV device, as represented by an oximeter, recording only pulse rate and oxygen saturation. A recent publication from the American College of Physicians summarised validation studies with simultaneous recording of home testing systems during polysomnography and stated that “type III monitors have the ability to predict apnea-hypopnea index scores suggestive of OSA”.8 It added that “direct comparison between type III and type IV monitors was not possible” but “current evidence supports greater diagnostic accuracy with type III monitors than type IV monitors”.

Our study was designed to compare the ability of oximetry alone and of type III multichannel sleep polygraphy performed during unmonitored home testing to predict the apnoea–hypopnoea index (AHI) measured during in-laboratory polysomnography. For the type III system we chose the ResMed ApneaLink Plus (ResMed, San Diego, California, USA). A number of studies have shown good agreement between the AHI recorded with full polysomnography and the simultaneously measured AHI recorded by the ApneaLink, a single-channel nasal flow device.9–11 Other studies have tested two-channel and three-channel versions of the ApneaLink.12–14 The ApneaLink Plus is a type III device that measures respiratory effort, pulse oximetry and the pulse rate in addition to nasal airflow. While it has, to date, been assessed with only one validation study,15 it should be at least as accurate as the single channel nasal flow to predict the AHI since, according to current rules, a hypopnoea cannot be scored without an oxygen desaturation.16

Materials and methods

Adult patients scheduled for in-laboratory polysomnography with a diagnosis of suspected sleep apnoea were invited to participate with no exclusions for comorbidity. We attempted to do the home testing within 2 weeks of the polysomnography.

Stand-alone oximetry was performed with the Pulsox-300i oximeter (Konica Minolta, Inc, Osaka, Japan), which uses a finger probe connected to a recording module strapped to the wrist. The oxygen saturation and pulse rate were recorded as one sample per second. The oxygen desaturation index (ODI) was calculated with the Profox software (Profox Associates, Escondido, California, USA) using the criterion of a 4% decrease from the baseline to identify a desaturation event. In our data analysis, we used the ODI reported by the software with no technician intervention to exclude artefacts or portions of the record with a poor-quality signal. Tests were considered successful if there were at least 4 h of valid recording. The result of this test we call ODISOX.

The ApneaLink Plus records oxygen saturation and pulse rate with a finger probe, nasal airflow with a nasal pressure cannula and respiratory effort with a pneumatic sensor belt. The software reports the ‘apnoea–hypopnoea index’ or, according to current terminology, the respiratory disturbance index (RDI) using the 4% desaturation criterion and the ‘recommended rules’ of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine to score a hypopnoea.16 The test was considered successful if there were at least 4 h of valid recording on both oximetry and nasal airflow channels.

The ApneaLink Plus records were also manually scored after they were exported as European Data Format files into the Philips G3 Sleepware software (Philips Respironics, Carlsbad, California, USA). The records were scored by a sleep technologist blind to the results of the polysomnography, and in most cases the polysomnogram and the ApneaLink Plus records were scored by different technologists. Again we used a 4% desaturation and the ‘recommended rules’ to score a hypopnoea. We, therefore, reported four values from the ApneaLink Plus: the raw RDI and ODI from the device software (RDIRAW and ODIRAW) and the manually scored values (RDIMAN and ODIMAN).

Participants were instructed to put the two oximeter probes on different fingers of the same hand, but the choice of which probe was put on which finger was left to them.

The laboratory polysomnography was performed using the Compumedics Profusion Sleep 4 (Compumedics USA, Charlotte, North Carolina, USA) or the Philips Respironics Alice 5 systems. If a split-night test was conducted using part of the night for continuous positive airway pressure titration, only the diagnostic segment of the night was used for the analysis. Those tests that had been scored using the ‘alternative rules’ for a hypopnoea, requiring only a 3% desaturation, were rescored with the ‘recommended rules’ requiring a 4% desaturation.16

Statistical analysis

Statistical calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism V.5 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). A normal distribution of the data was not expected and so the non-parametric Spearman's rs was used for the tests for correlation. Bland-Altman plots were used to determine the biases between the AHI, and the several event rates that were calculated from the home tests and between RDIMAN and other estimates of RDI and ODI. We calculated receiver–operator curves to analyse the sensitivity and specificity of the home testing event rates to predict the AHI using cut-off values of 5, 10 and 15 events per hour. A second set of receiver–operator curves was calculated to test ODISOX, ODIRAW, ODIMAN and RDIRAW versus RDIMAN. RDIMAN was considered the 'best' of the home testing measurements.

Results

One hundred and thirty-seven participants consented to the study (figure 1). Of these, 128 completed polysomnography. Seven cancelled the polysomnography or it was not approved by their insurers. Home testing was attempted by 123 participants, but the failure rate was unexpectedly high for both oximetry and the ApneaLink Plus. This may have been explained partly by the difficulty in keeping the two oximeter probes in place and perhaps by the participants not being highly motivated to get a successful study because they knew that they would be getting the ‘gold standard’ polysomnogram. Also contributing to the failures is the fact that we required that recordings be successful with both ApneaLink Plus and stand-alone oximeter. In addition, the ApneaLink Plus was ‘penalised’ by the requirement that we have 4 h of valid signals from both flow and oximeter channels. In the real world, the redundancy of flow and saturation channels would have allowed a clinically useful interpretation even if there were valid data from only one channel. Three participants were excluded from the analysis because they used the ApneaLink Plus and the stand-alone oximeter on different nights.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant recruitment (PSG, polysomnography; SOX, stand-alone oximeter).

We were left with 73 participants who had at least 4 h of successful recording with both systems. The interval between home testing and the polysomnography was 2 weeks or less in 62 (85%) of participants (median 8 days, IQR 3–11, maximum 40).

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of these participants. Although we had a wide range of ages and body mass index, patients with comorbid conditions were under-represented. Specifically, we had no participants with a history of atrial fibrillation or of heart failure. The patients with sleep apnoea in our database of 737 with the condition were older, somewhat more obese and had more severe sleep apnoea (median age 58.0 years, body mass index 30.8, AHI 21.9) than the participants in this study. Twenty-three participants had an AHI of less than 5, 22 had 5–15 (mild), 18 had 15–30 (moderate) and 10 had more than 30 (severe sleep apnoea). Only three of our participants showed significant central events on the ApneaLink Plus (more than 5 central apnoeas per hour, and 50% or more of the RDI were central apnoeas).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical information for the 73 participants included in the analysis

| Age (median, IQR, range) | 53.5, 43.3–66.0, 23–86 |

| BMI (median, IQR, range) | 29.8, 26.6–34.4, 20.2–50.8 |

| ESS (median, IQR, range) | 8, 4–12, 0–19 |

| AHI (median, IQR, range) | 9.4, 4.1–20.0, 0–87 |

| Male (number, %) | 53, 72.6 |

| Hypertension (number, %) | 30, 40.5 |

| Diabetes (number, %) | 9, 12.2 |

| Atrial fibrillation (number, %) | 0, 0.0 |

AHI, apnoea–hypopnoea index from the polysomnogram; BMI, body mass index, kg/m2; ESS, Epworth sleepiness scale.

The 50 participants who attempted home testing with technically unsatisfactory or no data on one or both systems are shown in table 2. They differed little in their demographics from those who were successful. However, their AHI was higher (p<0.01 by Mann-Whitney U test) and they included two participants with atrial fibrillation.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical information for the 50 participants not included in the analysis because of technical failure or no data for home testing

| Age (median, IQR, range) | 56.0, 48.0–67.0, 27–81 |

| BMI (median, IQR, range) | 28.7, 26.1–34.2, 21.0–53.6 |

| ESS (median, IQR, range) | 9, 6–12, 3–22 |

| AHI (median, IQR, range) | 16.9, 8.8–50.9, 0–125 |

| Male (number, %) | 39, 78.0 |

| Hypertension (number, %) | 17, 34.0 |

| Diabetes (number, %) | 5, 10.0 |

| Atrial fibrillation (number, %) | 2, 4.0 |

AHI, apnoea–hypopnoea index from the polysomnogram; BMI, body mass index, kg/m2; ESS, Epworth sleepiness scale.

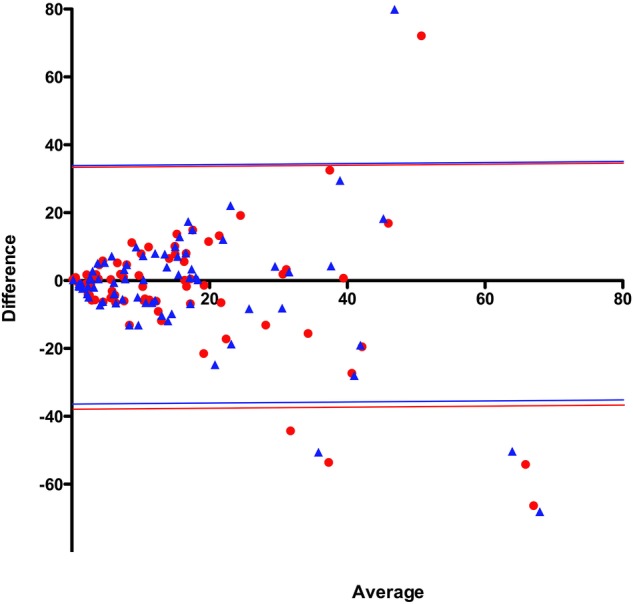

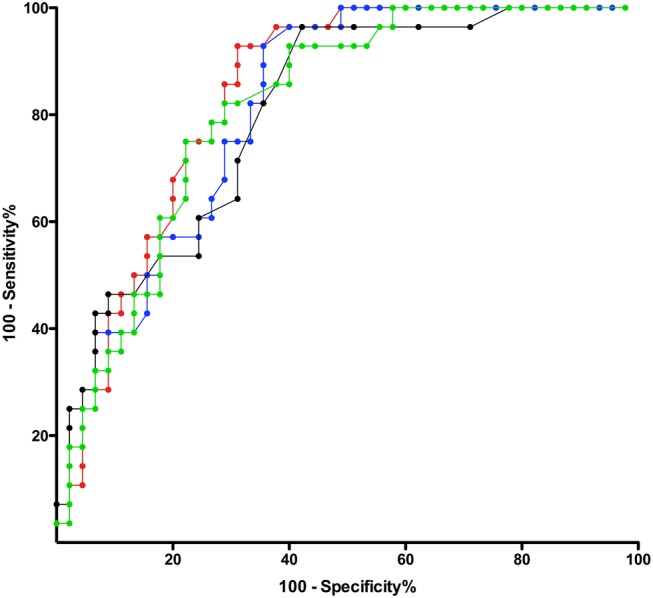

Tables 3 and 4 show the comparisons of the various calculations of the home testing respiratory event rates with the AHI measured during the laboratory polysomnogram. Only small differences were seen between the various home testing values and there was a large overlap of the confidence limits. Table 4 shows that, in terms of predicting a laboratory apnoea-hypoxia index above various thresholds, ODISOX and ODIRAW performed almost as well as RDIMAN. Specifically, comparison of the agreements of the AHI with RDIMAN and with ODIMAN shows that addition of the nasal flow and respiratory effort channels adds little to the ability of oximetry alone to predict the results of the laboratory polysomnography. Figure 2 shows the Bland-Altman plot for the laboratory AHI versus RDIMAN and ODIMAN. Figures 3 and 4 show the receiver-operator characteristic curves for RDIMAN and the three different values of ODI for cut-off values of the AHI of 5, 10 and 15. Spearman’s r and the receiver–operator characteristic areas under the curve suggest that RDIMAN had a slight advantage over the other home testing measurements to predict the AHI while the Bland-Altman plot shows that ODIMAN and ODISOX did slightly better.

Table 3.

Statistical calculations for the laboratory polysomnogram versus home testing

| Correlation |

Bland-Altman |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rS | 95% Confidence limits | Bias | SD | 95% Confidence limits | |

| AHI vs ODISOX | 0.638 | 0.473 to 0.760 | 1.7 | 15.1 | −27.9 to 31.3 |

| AHI vs ODIRAW | 0.645 | 0.482 to 0.765 | −2.6 | 16.9 | −35.7 to 30.5 |

| AHI vs ODIMAN | 0.683 | 0.533 to 0.792 | −1.4 | 17.7 | −36.1 to 33.4 |

| AHI vs RDIRAW | 0.688 | 0.539 to 0.795 | −2.4 | 16.7 | −35.1 to 30.3 |

| AHI vs RDIMAN | 0.717 | 0.578 to 0.815 | −2.4 | 18.0 | −37.7 to 32.9 |

AHI, apnoea–hypopnoea index from the polysomnogram; ODI, oxygen desaturation index; RDI, respiratory disturbance index from the ApneaLink Plus; rs, Spearman's rank order correlation coefficient; subscript MAN is for manually scored, RAW for computer-reported raw value, SOX for stand-alone oximeter.

Table 4.

ROC calculations using the laboratory polysomnogram apnoea–hypopnoea index as the gold standard

| ROC for AHI ≥5 |

ROC for AHI ≥10 |

ROC for AHI ≥15 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | 95% Confidence limits | AUC | 95% Confidence limits | AUC | 95% Confidence limits | |

| AHI vs ODISOX | 0.827 | 0.728 to 0.925 | 0.816 | 0.718 to 0.914 | 0.815 | 0.718 to 0.912 |

| AHI vs ODIRAW | 0.840 | 0.749 to 0.931 | 0.811 | 0.716 to 0.907 | 0.803 | 0.703 to 0.902 |

| AHI vs ODIMAN | 0.857 | 0.770 to 0.945 | 0.826 | 0.733 to 0.918 | 0.816 | 0.721 to 0.910 |

| AHI vs RDIRAW | 0.849 | 0.764 to 0.935 | 0.826 | 0.730 to 0.922 | 0.836 | 0.741 to 0.931 |

| AHI vs RDIMAN | 0.881 | 0.805 to 0.958 | 0.835 | 0.744 to 0.926 | 0.840 | 0.751 to 0.929 |

AHI, apnoea–hypopnoea index from the polysomnogram; AUC, area under the curve; ODI, oxygen desaturation index; RDI, respiratory disturbance index from the ApneaLink Plus; ROC, receiver–operator characteristic; subscript MAN is for manually scored, RAW for computer-reported raw value, SOX for stand-alone oximeter.

Figure 2.

Bland-Altman plot of laboratory apnoea–hypopnoea index versus home testing event rates. RDIMAN shown as red circles; ODIMAN shown as blue triangles. The coloured horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence limits (ODI, oxygen desaturation index; RDI, respiratory disturbance index; subscript MAN is for manually scored).

Figure 3.

Receiver–operator characteristic curves for home testing event rates versus laboratory apnoea–hypopnoea index ≥5. RDIMAN is in red; ODIMAN is in blue; ODIRAW is in black; ODISOX is green (ODI, oxygen desaturation index; RDI, respiratory disturbance index; subscript MAN is for manually scored, RAW for computer-reported raw value, SOX for stand-alone oximeter).

Figure 4.

Receiver–operator characteristic curves for home testing event rates versus laboratory apnoea–hypopnoea index ≥15. RDIMAN is in red; ODIMAN is in blue; ODIRAW is in black; ODISOX is green (ODI, oxygen desaturation index; RDI, respiratory disturbance index; subscript MAN is for manually scored, RAW for computer-reported raw value, SOX for stand-alone oximeter).

In tables 5 and 6, we show the agreement between RDIMAN, the best predictor of the laboratory AHI, and the other event rates calculated from the home test. RDIMAN differed only slightly from RDIRAW and the three versions of the ODI.

Table 5.

Statistical calculations for the technician-scored RDI versus other home testing values

| Correlation |

Bland-Altman |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rS | 95% Confidence limits | Bias | SD | 95% Confidence limits | |

| RDIMAN vs ODISOX | 0.899 | 0.841 to 0.936 | 4.06 | 9.60 | −14.8 to 22.9 |

| RDIMAN vs ODIRAW | 0.926 | 0.882 to 0.953 | −0.26 | 5.63 | −11.3 to 10.8 |

| RDIMAN vs ODIMAN | 0.946 | 0.913 to 0.966 | 1.00 | 4.89 | −8.6 to 10.6 |

| RDIMAN vs RDIRAW | 0.944 | 0.911 to 0.965 | −0.07 | 3.77 | −7.5 to 7.3 |

ODI, oxygen desaturation index; RDI, respiratory disturbance index from the ApneaLink Plus; rS, Spearman’s rank order correlation coefficient; subscript MAN is for manually scored, RAW for computer-reported raw value, SOX for stand-alone oximeter.

Table 6.

ROC calculations using the technician-scored RDI as the gold standard

| ROC for AHI ≥5 |

ROC for AHI ≥10 |

ROC for AHI ≥15 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | 95% Confidence limits | AUC | 95% Confidence limits | AUC | 95% Confidence limits | |

| RDIMAN vs ODISOX | 0.966 | 0.921 to 1.000 | 0.921 | 0.857 to 0.986 | 0.965 | 0.929 to 1.000 |

| RDIMAN vs ODIRAW | 0.961 | 0.920 to 1.000 | 0.942 | 0.883 to 1.000 | 0.976 | 0.949 to 1.000 |

| RDIMAN vs ODIMAN | 0.988 | 0.968 to 1.000 | 0.953 | 0.903 to 1.000 | 0.974 | 0.945 to 1.000 |

| RDIMAN vs RDIRAW | 0.950 | 0.950 to 0.998 | 0.956 | 0.907 to 1.000 | 0.995 | 0.983 to 1.000 |

AHI, apnoea–hypopnoea index from the polysomnogram; AUC, area under the curve; ODI, oxygen desaturation index; RDI, respiratory disturbance index from the ApneaLink Plus; ROC, receiver–operator characteristic; subscript MAN is for manually scored, RAW for computer-reported raw value, SOX for stand-alone oximeter.

Discussion

This the first study that directly compares the ability of home testing with oximetry alone versus a type III device to predict the AHI based on laboratory polysomnography performed on a different night. There have been earlier studies in parallel groups comparing oximetry-based devices with polysomnography.17 18

There was only fair agreement between the results of the home testing and the in-laboratory polysomnography. Some of the sources of the poor agreement would be differences in sleep quality between the home and the laboratory environment, and the fact that the event rate was calculated for the EEG-based sleep time in the polysomnogram and for the recording time in the home tests. In addition, many of the polysomnograms were split-night studies in which slow-wave sleep might be over-represented and rapid eye movement sleep under-represented. However, the greatest source of the difference was probably night-to-night variation. For example, Levendowski et al19 reported a bias of 7.0 and a SD of 16.8 in a Bland-Altman plot of the AHI from two laboratory polysomnograms performed a month apart. Their SD was similar to what we found when we compared the laboratory AHI with the home testing event rate, measured on a different night, by any of the parameters we calculated. Chediak et al20 found that the AHI differed by 10 or more in 12 of 37 participants undergoing laboratory polysomnography on two successive nights.

However, our study was not intended to test the reliability of either home sleep polygraphy or stand-alone oximetry compared with laboratory polysomnography. Rather, we wanted to see if the addition of respiratory flow and effort channels to pulse oximetry significantly improved the ability of home testing to predict the AHI measured during an attended laboratory polysomnography. Our results suggest that it does not.

Given the currently accepted scoring rules, most respiratory events will be associated with a desaturation. The only events that would be scored differently by the ApneaLink Plus and by oximetry alone would be apnoeas without a desaturation and desaturations without an apnoea or a hypopnoea. Therefore, it is not surprising that, in the patients we studied, the RDI and the ODI agreed closely. Had we studied an older population with more comorbid cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease our results may have been different; however, those are patients for whom home testing is not recommended.7

We did see some difference between the ODI reported by the ApneaLink Plus and the stand-alone oximeter. This could be explained in part by the different models of oximeter and the presumably different proprietary scoring algorithms used by the two systems. Also, there were some studies in which the valid recording time differed substantially between the two oximeters. So long as there were at least 4 h of valid signals for both, we included them in the analysis.

Validation studies using the ApneaLink and laboratory polysomnography simultaneously have shown that the manually scored RDI agrees better with the AHI than the RDI reported by the software.10 21 Our results show that RDIMAN agreed slightly better than RDIRAW with the laboratory AHI but, again, the differences were small compared with the confidence limits. Our Bland-Altman plots did not show the large differences between the manually scored and the computer-scored RDI for the ApneaLink Plus that were reported in a recent paper by Aurora et al.22 Unlike the 2014 paper from Masa et al,23 we did not see much difference between the receiver–operator characteristic curves for mild, moderate and severe sleep apnoea when comparing the laboratory polysomnography with home testing performed on a different night. However, they had studied a much larger group of participants than we did and they used the ApneaLink, which records only nasal airflow, rather than the four-channel ApneaLink Plus.

A 2014 guideline published by the American College of Physicians “recommends polysomnography for diagnostic testing in patients suspected of obstructive sleep apnea” but also “recommends portable sleep monitors in patients without serious comorbidities as an alternative to polysomnography when polysomnography is not available for diagnostic testing”.8 This paper reviewed the literature comparing type III and IV monitors with polysomnography and stated that direct comparison between the two types of monitors was not possible. However, it added that “indirect evidence from studies comparing each monitor with PSG suggested that type III monitors performed better than type IV monitors in predicting AHI scores suggestive of OSA”. Many type IV devices include other channels, such as pulse rate, but their scoring of respiratory events is based mainly on the ODI. Our study shows that if there is any advantage of the type III ApneaLink Plus compared with oximetry alone, the difference is small and probably clinically insignificant when compared with night-to-night variations between tests, regardless of the type of equipment used.

While sleep physicians may prefer the, probably slight, advantage of type III testing over simple oximetry for home testing of patients with suspected sleep apnoea, the low cost and availability of oximetry make it an attractive alternative in situations where the burden of undiagnosed sleep apnoea remains high. Even in the USA, underdiagnosis of sleep apnoea was a significant problem a decade or so ago, and it has probably not changed much since then.24

Although laboratory polysomnography provides much more information about a patient’s sleep than type III testing, its cost makes multiple night studies prohibitively expensive in most clinical situations. Some of the advantages of more detailed information are offset by the problem of night-to-night variations,19 20 25–27 which appears to be less with home testing.28–30 In the patient with no comorbidity and a high pretest probability of sleep apnoea, several nights of oximetry would certainly be less costly, and could be a more reliable diagnostic test than a single night of laboratory polysomnography. The high failure rate of home testing that we observed in this study was not observed in a large primary care case finding study and we believe it is largely explained by our requirement for 4 h of valid data from two oximeters plus the nasal flow channel of the ApneaLink Plus.31

Low-cost oximeters that can be used with a smart phone are readily available to the public and their use can be expected to increase rapidly with the growing popularity of ‘iHealth’ phone applications.32 The day is probably not far off when a pulse oximeter will be integrated into a wristwatch and there will be ‘apps’ that can display the ODI. More than three decades have passed since diagnostic testing for sleep disorders entered the main stream of clinical medicine and still we see educated patients with good health insurance presenting with severe and unrecognised obstructive sleep apnoea. A simple and self-administered test such as home oximetry may be required to get these people the help they need.

Wider availability of home oximetry can be expected to decrease one of the barriers to effective treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea by identifying undiagnosed patients. Even if type III devices provide a slight gain in sensitivity and specificity over stand-alone oximetry, the type of device used for diagnosis has little effect on the most important treatment outcome—the adherence to continuous positive airway pressure.33 34

Conclusions

The ability of home testing with the ApneaLink Plus to predict the apnoea–hypopnoea index measured during in-laboratory polysomnography hardly differed when it was based on either the software-calculated oxygen desaturation index or on the technician-scored respiratory disturbance index.

The differences between the oxygen desaturation index and the respiratory disturbance index measured during home testing are small compared with the reported night-to-night variation of the apnoea–hypopnoea index.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Kep Wadiak, David Parenteau and Sophie Pham for their skilled scoring of the polysomnograms and the home polygraphs. The ApneaLink Plus devices were provided by ResMed Corp. (San Diego, California, USA).

Footnotes

Contributors: AD designed the study, analysed the data and wrote a draft of the manuscript. RTL, SLA and DL contributed to the acquisition of data. DFK, LEK, RMG and DL contributed to the design of the study and the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript and gave approval for the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Scripps Health Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Scripps Office for the Protection of Research Subjects (IRB-11–5671).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Antic NA, Buchan C, Esterman A et al. A randomized controlled trial of nurse-led care for symptomatic moderate-severe obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:501–8. 10.1164/rccm.200810-1558OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohning N, Schultheiss B, Eilers S et al. Comparability of pulse oximeters used in sleep medicine for the screening of OSA. Physiol Meas 2010;31:875–88. 10.1088/0967-3334/31/7/001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malbois M, Giusti V, Suter M et al. Oximetry alone versus portable polygraphy for sleep apnea screening before bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2010;20:326–31. 10.1007/s11695-009-0055-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung F, Liao P, Elsaid H et al. Oxygen desaturation index from nocturnal oximetry: a sensitive and specific tool to detect sleep-disordered breathing in surgical patients. Anesth Analg 2012;114:993–1000. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318248f4f5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niijima K, Enta K, Hori H et al. The usefulness of sleep apnea syndrome screening using a portable pulse oximeter in the workplace. J Occup Health 2007;49:1–8. 10.1539/joh.49.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou J, Guan J, Yi H et al. An effective model for screening obstructive sleep apnea: a large-scale diagnostic study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e80704 10.1371/journal.pone.0080704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 2007;3:737–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qaseem A, Dallas P, Owens DK et al. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:210–20. 10.7326/M12-3187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinreich G, Armitstead J, Topfer V et al. Validation of ApneaLink as screening device for Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Sleep 2009;32:553–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.BaHammam AS, Sharif M, Gacuan DE et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of manual and automatic scoring of a single airflow channel in patients with a high probability of obstructive sleep apnea. Med Sci Monit 2011;17:MT13–19. 10.12659/MSM.881379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng SS, Chan TO, To KW et al. Validation of a portable recording device (ApneaLink) for identifying patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Intern Med J 2009;39:757–62. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01827.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gantner D, Ge JY, Li LH et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a questionnaire and simple home monitoring device in detecting obstructive sleep apnoea in a Chinese population at high cardiovascular risk. Respirology 2010;15:952–60. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nigro CA, Dibur E, Malnis S et al. Validation of ApneaLink Ox™ for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath 2013;17:259–66. 10.1007/s11325-012-0684-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fredheim JM, Roislien J, Hjelmesaeth J. Validation of a portable monitor for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in morbidly obese patients. J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10:751–7, 57A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesser DJ, Haddad GG, Bush RA et al. The utility of a portable recording device for screening of obstructive sleep apnea in obese adolescents. J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8:271–7. 10.5664/jcsm.1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL Jr et al. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Issa FG, Morrison D, Hadjuk E et al. Digital monitoring of sleep-disordered breathing using snoring sound and arterial oxygen saturation. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;148(4 Pt 1):1023–9. 10.1164/ajrccm/148.4_Pt_1.1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li CK, Flemons WW. State of home sleep studies. Clin Chest Med 2003;24:283–95. 10.1016/S0272-5231(03)00018-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levendowski DJ, Zack N, Rao S et al. Assessment of the test-retest reliability of laboratory polysomnography. Sleep Breath 2009;13:163–7. 10.1007/s11325-008-0214-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chediak AD, Acevedo-Crespo JC, Seiden DJ et al. Nightly variability in the indices of sleep-disordered breathing in men being evaluated for impotence with consecutive night polysomnograms. Sleep 1996;19:589–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nigro CA, Dibur E, Aimaretti S et al. Comparison of the automatic analysis versus the manual scoring from ApneaLink device for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Sleep Breath 2011;15:679–86. 10.1007/s11325-010-0421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aurora RN, Swartz R, Punjabi NM. Misclassification of obstructive sleep apnea severity with automated scoring of home sleep recordings. Chest 2015;147:719–27. 10.1378/chest.14-0929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masa JF, Duran-Cantolla J, Capote F et al. Effectiveness of home single-channel nasal pressure for sleep apnea diagnosis. Sleep 2014;37:1953–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapur V, Strohl KP, Redline S et al. Underdiagnosis of sleep apnea syndrome in US communities. Sleep Breath 2002;6:49–54. 10.1055/s-2002-32318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmadi N, Shapiro GK, Chung SA et al. Clinical diagnosis of sleep apnea based on single night of polysomnography vs. two nights of polysomnography. Sleep Breath 2009;13:221–6. 10.1007/s11325-008-0234-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gouveris H, Selivanova O, Bausmer U et al. First-night-effect on polysomnographic respiratory sleep parameters in patients with sleep-disordered breathing and upper airway pathology. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2010;267:1449–53. 10.1007/s00405-010-1205-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newell J, Mairesse O, Verbanck P et al. Is a one-night stay in the lab really enough to conclude? First-night effect and night-to-night variability in polysomnographic recordings among different clinical population samples. Psychiatry Res 2012;200:795–801. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quan SF, Griswold ME, Iber C et al. Short-term variability of respiration and sleep during unattended nonlaboratory polysomnography—the Sleep Heart Health Study. [corrected] Sleep 2002;25:843–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stepnowsky CJ Jr, Orr WC, Davidson TM. Nightly variability of sleep-disordered breathing measured over 3 nights. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;131:837–43. 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levendowski D, Steward D, Woodson BT et al. The impact of obstructive sleep apnea variability measured in-lab versus in-home on sample size calculations. Int Arch Med 2009;2:2 10.1186/1755-7682-2-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burgess KR, Havryk A, Newton S et al. Targeted case finding for OSA within the primary care setting. J Clin Sleep Med 2013;9:681–6. 10.5664/jcsm.2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sands SA, Owens RL. Does my bed partner have OSA? There's an app for that! J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10:79–80. 10.5664/jcsm.3366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitelaw WA, Brant RF, Flemons WW. Clinical usefulness of home oximetry compared with polysomnography for assessment of sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:188–93. 10.1164/rccm.200310-1360OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mulgrew AT, Fox N, Ayas NT et al. Diagnosis and initial management of obstructive sleep apnea without polysomnography: a randomized validation study. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:157–66. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]