Abstract

The small East African Shorthorn Zebu (EASZ) is the main indigenous cattle across East Africa. A recent genome wide SNP analysis revealed an ancient stable African taurine x Asian zebu admixture. Here, we assess the presence of candidate signatures of positive selection in their genome, with the aim to provide qualitative insights about the corresponding selective pressures. Four hundred and twenty-five EASZ and four reference populations (Holstein-Friesian, Jersey, N’Dama and Nellore) were analysed using 46,171 SNPs covering all autosomes and the X chromosome. Following FST and two extended haplotype homozygosity-based (iHS and Rsb) analyses 24 candidate genome regions within 14 autosomes and the X chromosome were revealed, in which 18 and 4 were previously identified in tropical-adapted and commercial breeds, respectively. These regions overlap with 340 bovine QTL. They include 409 annotated genes, in which 37 were considered as candidates. These genes are involved in various biological pathways (e.g. immunity, reproduction, development and heat tolerance). Our results support that different selection pressures (e.g. environmental constraints, human selection, genome admixture constrains) have shaped the genome of EASZ. We argue that these candidate regions represent genome landmarks to be maintained in breeding programs aiming to improve sustainable livestock productivity in the tropics.

The history of African cattle is complex, with two cattle subspecies having contributed to the genetic make-up of the majority of today’s African indigenous cattle1: the humped zebu or indicine cattle Bos taurus indicus - domesticated in South Asia2, and the humpless taurine Bos taurus taurus - domesticated in the Near East3. Also, introgression of the local African auroch B. primigenius africanus into some African cattle populations remains possible4. Historically, the first evidence of taurine domestic cattle on the African continent dates from ~5000 years B.C. Asian indicine cattle were introduced later with their first documented occurrence in Egypt at ~2000 years B.C5. They entered the continent through the Horn of Africa, becoming established on its eastern part with the development of the Swahili civilization from ~700 years AD1. These cattle crossbred with the local African taurine, an ongoing process which might have accelerated following the rinderpest epidemics of the late 19th century1. Today all African cattle, independent of their phenotypes (humpless, thoracic or cervico-thoracic humped animals), carry a taurine mitochondrial DNA suggesting a zebu male-mediated introgression5,6, although selection against zebu mitochondrial and/or maternal genetic drift in favour of taurine mtDNA remains possible.

The indigenous small East African Shorthorn Zebu (EASZ) is commonly found in Western Kenya where they represent the main type of cattle7. As for other indigenous livestock owned by smallholder crop-livestock farmers, natural environmental conditions represent major selection pressures. Consequently, indigenous East African zebu cattle are often favoured over the exotic taurine cattle by local farmers due to their better survivability under minimal veterinary care7. EASZ cattle show a degree of resistance to Rhipicephalus appendiculatus ticks infestation8, as well tolerance to poor quality forage7. They would be expected to display some level of tolerance – resistance to pathogens common in East Africa, e.g. Anaplasma marginale, Babesia bigemina, Haemonchus placei and Theileria parva9,10,11. However, a recent study has shown that in the absence of any veterinary intervention, 16% of newborn calves still died from natural causes during their first year10. Specifically, East Coast Fever and haemonchosis have been identified as the main causes of death11. It emphasizes that although more resistant compared to exotic population, EASZ are not fully resistant to these local infectious diseases. In addition, as a zebu type of cattle, EASZ would be expected to show some level of thermotolerance for higher temperature, which might include enhanced thermoregulation, higher fertility and growth rate compared to northern hemisphere exotic cattle exposed to the same environment12.

At the genome level, EASZ has now been shown to be an ancient stabilized admixed zebu x taurine type of cattle13. Recent studies have revealed European cattle introgression in some animals and, to some extent, inbreeding in the population13,14. Importantly, both have been shown to be associated with increased probability of death and/or clinical episodes supporting genetic components for the local adaptability (e.g. diseases challenges) of the EASZ to its environment14.

Several studies using genome-wide SNPs have been conducted exploring the genomes of sheep, pigs and cattle to identify signatures of selection following domestication15,16,17,18. In cattle, autosomal genome-wide SNP analysis of different tropical-adapted populations in West Africa18,19,20, the Caribbean islands (Creole cattle)16, and a synthetic European taurine x Asian zebu (Senepol cattle)21 have identified several genome regions under positive selection. These include genes involved in the regulation of innate and adaptive immune system, male reproduction characteristics, skin and hair structure. Up to now no such studies have been conducted in East African cattle populations.

Through three separate genome-wide SNPs analyses, we report here the identification of candidate signatures for positive selection in the genome of EASZ both on the autosomes and the sex chromosome X. These were identified through the analysis of genetic differentiation (FST) between EASZ and four reference populations (Holstein-Friesian, Jersey, N’Dama and Nellore), as well as through the identification of regions showing extended haplotype homozygosity within EASZ (iHS), and between EASZ and the reference populations combined (Rsb). We compare our finding with previous studies on tropical cattle and commercial breeds. We identify candidate regions of positive selection unique to EASZ as well as previously reported regions in other tropically adapted cattle and commercial breeds. Moreover, several of these overlap with Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) previously identified through genome-wide association studies.

Methods

SNPs genotyping and quality control

Non-European taurine introgressed EASZ (n = 425), from 20 randomly selected sub-locations, covering 4 distinct ecological zones in Western and Nyanza provinces of Kenya10,13 were genotyped using the Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip v.1. The array comprises SNPs covering the 29 bovine autosomes, the sex chromosome (BTA X) and three unassigned linkage groups22. SNP data for four reference cattle populations, Holstein-Friesian (n = 64), Jersey (n = 28), N’Dama (n = 25) and Nellore (n = 21) were obtained from the Bovine HapMap consortium23. Analyses were carried out on autosomes and BTA X separately to avoid any potential bias resulting from difference in effective population size. Quality control (QC) analyses for 54,334 autosomal and 1,341 BTA X markers were conducted through the check.marker function of the GenABEL package24 for R software version 2.15.1. The QC criteria were Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) threshold of 0.5%, which excluded 7,904 autosomal and 399 BTA X SNPs, and a SNP call rate threshold of 95%, which excluded 6,651 autosomal and 373 BTA X markers. Among these, 5,471 autosomal and 352 BTA X SNPs failed both criteria. A total of 45,250 autosomal (mean gap size = 55 kb and s.d. = 53 kb) and 921 BTA X SNPs (mean gap size = 161 kb and s.d. = 276 kb) remained for analysis.

Additional QC criteria included a minimum sample call rate of 95% and a maximum pairwise identity-by-state (IBS) of 95%, with the lower call rate animal being eliminated from the high IBS pair. From the autosomal SNPs, one EASZ sample was excluded for having a low call rate, whilst one EASZ and one Holstein-Friesian sample were excluded following the IBS criterion. As possible duplicate samples had already been removed following the autosomal QC steps, only the criterion of low call rate was applied for the BTA X analysis. It excluded a further two EASZ samples.

Inter-population genome-wide F ST analysis

Inter-population Wright’s FST25 analyses were conducted between the EASZ and each continental reference (European (Holstein-Friesian and Jersey), African (N’Dama) and Asian (Nellore)) population. FSTvalues (weighted by populations sample sizes) were calculated in sliding windows of 10 SNPs, overlapping by 5 SNPs. The upper 0.2% and 3% of the distribution of FST values were arbitrarily chosen as thresholds for the autosomes and BTA X analyses, respectively, taking into account the difference (9032 versus 184) in the number of windows analysed between the two sets of data. Candidate regions were defined if at least two overlapping windows passed the distribution threshold, taking the highest FST window as a candidate region interval.

Extended haplotype homozygosity (EHH)-derived statistics (iHS and Rsb)

Two EHH-derived statistics, the intra-population Integrated Haplotype Score (iHS)26 and inter-population Rsb27, were applied using the rehh package28 for R software. In the iHS analysis, the natural log of the ratio between the integrated EHH for the ancestral (iHHA) and derived allele (iHHD) was calculated for each genotyped SNP with MAF ≥ 0.5% in EASZ. As the standardised iHS values are normally distributed (Supplementary Fig. S1), a two-tailed Z-test was applied to identify statistically significant SNPs under selection with either an unusual extended haplotype of ancestral (positive iHS value) or derived alleles (negative iHS value). Two-sided P-values were derived as −log10(1-2|Ф(iHS)-0.5|), where Ф(iHS) represents the Gaussian cumulative distribution function. The ancestral and derived alleles of each SNP were inferred in two ways: (i) the ancestral allele was inferred as the most common allele within a dataset of 13 Bovinae species29; (ii) for SNPs with no information available in Decker et al.29, the ancestral allele were inferred as the most common allele in the complete dataset (EASZ and reference populations), consistent with the observation that in humans, the SNP alleles with higher frequency were likely to represent the ancestral allele30.

Inter-population Rsb analyses were conducted between the EASZ and each continental reference (European (Holstein-Friesian and Jersey), African (N’Dama) and Asian (Nellore)) population as well as with all the reference populations combined. The integrated EHHS (site-specific EHH) for each SNP in each population (iES) was calculated, and the Rsb statistics between populations were defined as the natural log of the ratio between iESpop1 and iESpop2. As the standardised Rsb values are normally distributed (Supplementary Fig. S1), a Z-test was applied to identify statistically significant SNPs under selection in EASZ (positive Rsb value). One-sided P-values were derived as −log10(1-Ф(Rsb)), where Ф(Rsb) represents the Gaussian cumulative distribution function. A Z-test was not applied to BTA X Rsb values due to their non-normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test; P-value <2.2 × 10−16, Supplementary Fig. S1). In both iHS and Rsb, −log10 (P-value) = 4, equivalent to a P-value of 0.0001, was used as a threshold to define significant iHS and Rsb values. Candidate regions were retained if two SNPs separated by ≤1 Mb passed this threshold. In case of Rsb analysis, the combined reference analysis was considered to define the candidate regions. A distance of 0.5 Mb in both directions from the most significant SNP within the iHS and Rsb candidate regions was used to define the candidate genome region interval. This distance was chosen based on the rate of change in the mean pairwise linkage disequilibrium statistic (r2), calculated by the r2fast function of the GenABEL package, binned over distance across the EASZ autosomes (Supplementary Fig. S2). Indeed, at larger distances we reach the r2 plateau. This extent of LD has been confirmed in eight cattle breeds (taurine and zebu) in a previous study31.

As a prerequisite for these two statistics, haplotypes were reconstructed through phasing the genotyped SNPs via fastPHASE software version 1.432, using the criteria K10 and T10, as in Utsunomiya et al.33, to reduce computation time. Population label information was used to estimate the phased haplotypes population background.

Functional characterization of the candidate regions

Genes within the candidate genome region intervals were retrieved from the Ensembl genome browser34 using the Bos taurus taurus genome assembly UMD 3.1, in which genes with boundaries ≤25 kb from the peak position (the most significant SNP in the candidate regions) were considered as candidate genes. Enriched functional annotation clusters were defined using functional annotation tool implemented in DAVID Bioinformatics resources 6.735 on both the exhaustive genes list and the candidate genes. As recommended by the software, an enrichment score of 1.3, equivalent to Fisher exact test P-value of 0.05, was used as a threshold for the identification of enriched clusters.

A list of all the previously identified bovine Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) and their coordinates were downloaded from the cattle QTL database (http://www.animalgenome.org/cgi-bin/QTLdb/BT/index) to obtain the overlapping QTL with the candidate genome regions.

Estimation of Asian zebu and African taurine ancestry proportions on BTA X

The Asian zebu and African taurine ancestry proportions on autosomes have been previously estimated by Mbole-Kariuki et al.13. Likewise admixture analysis via a Bayesian clustering method implemented in STRUCTURE software version 2.336 was conducted for the BTA X. The admixed model with independent allele frequencies was run for a burn-in period of 25,000 iterations and 50,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo steps for K = 3.

Estimation of excess or deficiency in Asian zebu ancestry at candidate regions

LAMP software version 2.437 was used to estimate the Asian zebu and African taurine ancestry proportions of each genotyped SNP. The genome-wide autosomal zebu ancestry proportion of 0.84 and African taurine ancestry proportion of 0.16 were used as the averaged admixture proportions α13. For the BTA X, zebu and African taurine ancestry proportions of 0.89 and 0.11, respectively, have been used as estimated by our STRUCTURE analysis. Five hundred generations, and a generation time of six years38, were assumed for the beginning of the admixture between Asian zebu and African taurine, in agreement with archaeological evidence supporting the first zebu arrival on the continent around 2000 BC5. A uniform recombination rate of 1 cM = 1 Mb was set as a pre-requisite of LAMP. The average excess/deficiency in Asian zebu ancestry (ΔAZ) was calculated for each SNP by subtracting the average estimated Asian zebu ancestry of the SNP from the average estimated Asian zebu ancestry of all SNPs. The calculation was conducted separately for autosomal and BTA X SNPs. The median ΔAZ for an arbitrary 5 SNPs window, two SNPs each side of the most significant candidate SNP, was considered to represent the ΔAZ of the candidate Rsb and iHS SNPs. This partially accounts for the possible inter-marker variation in Asian zebu ancestry proportion caused by genetic drift. For FST candidate regions, the median ΔAZ for the SNPs was considered.

Results

Candidate genome regions under positive selection

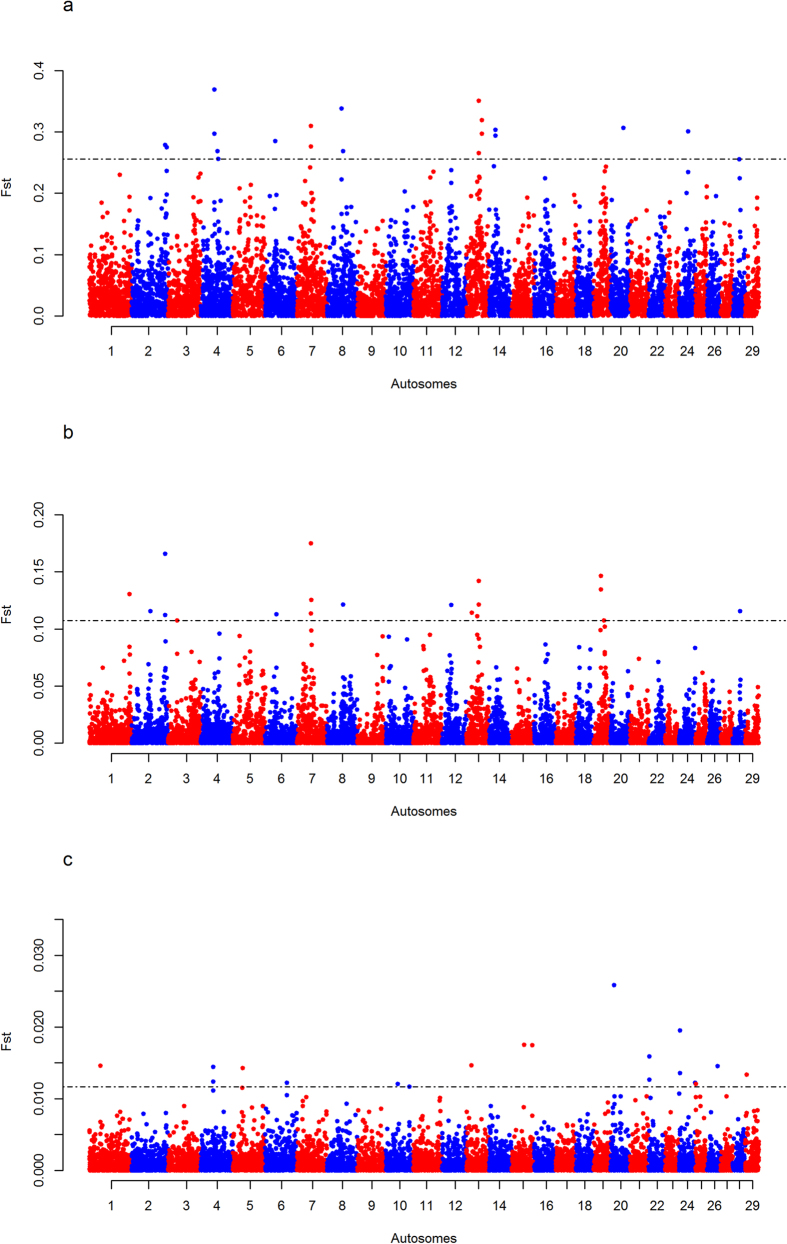

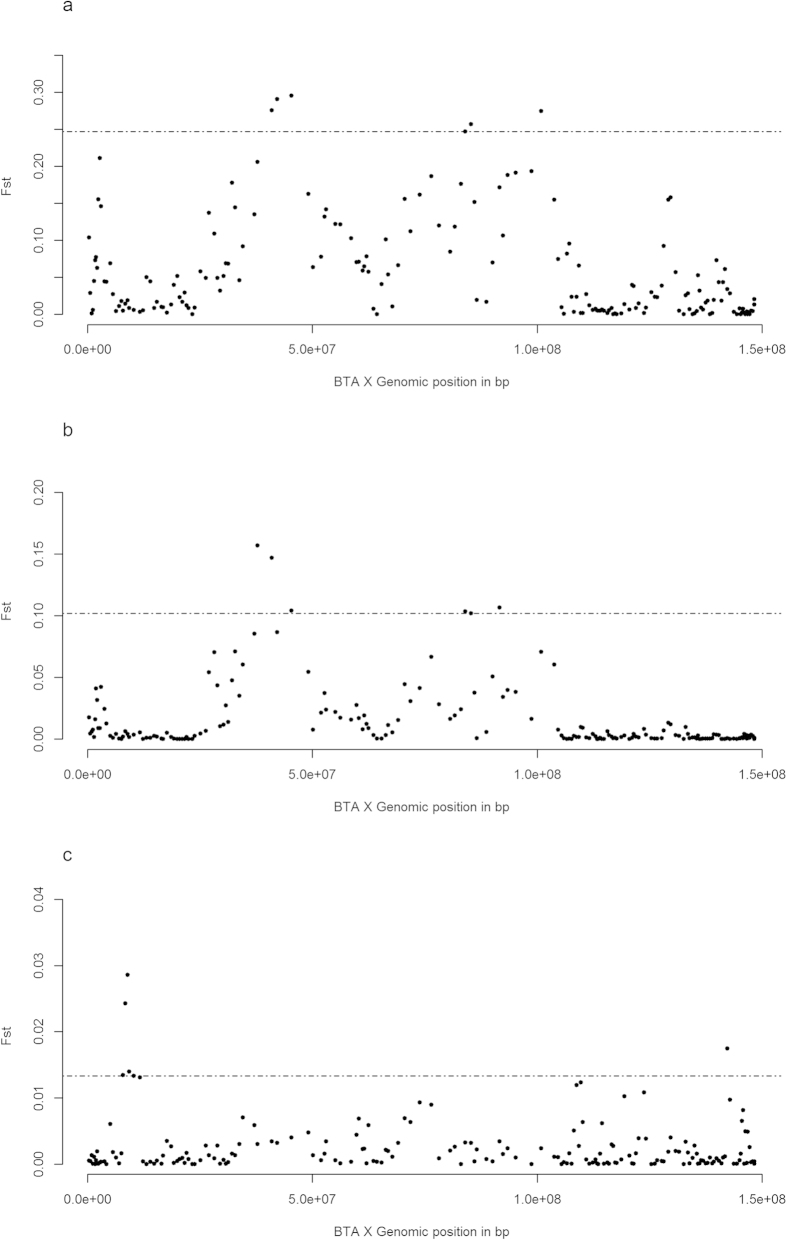

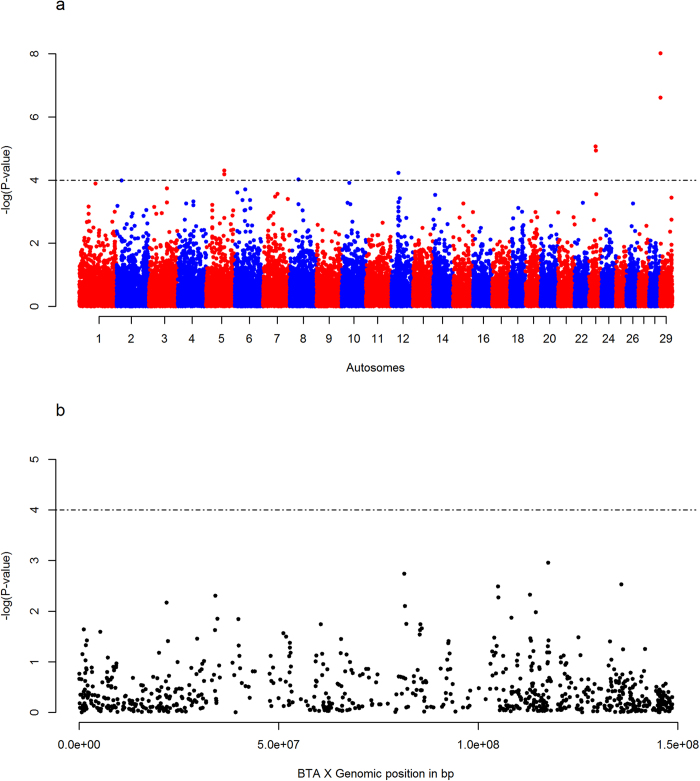

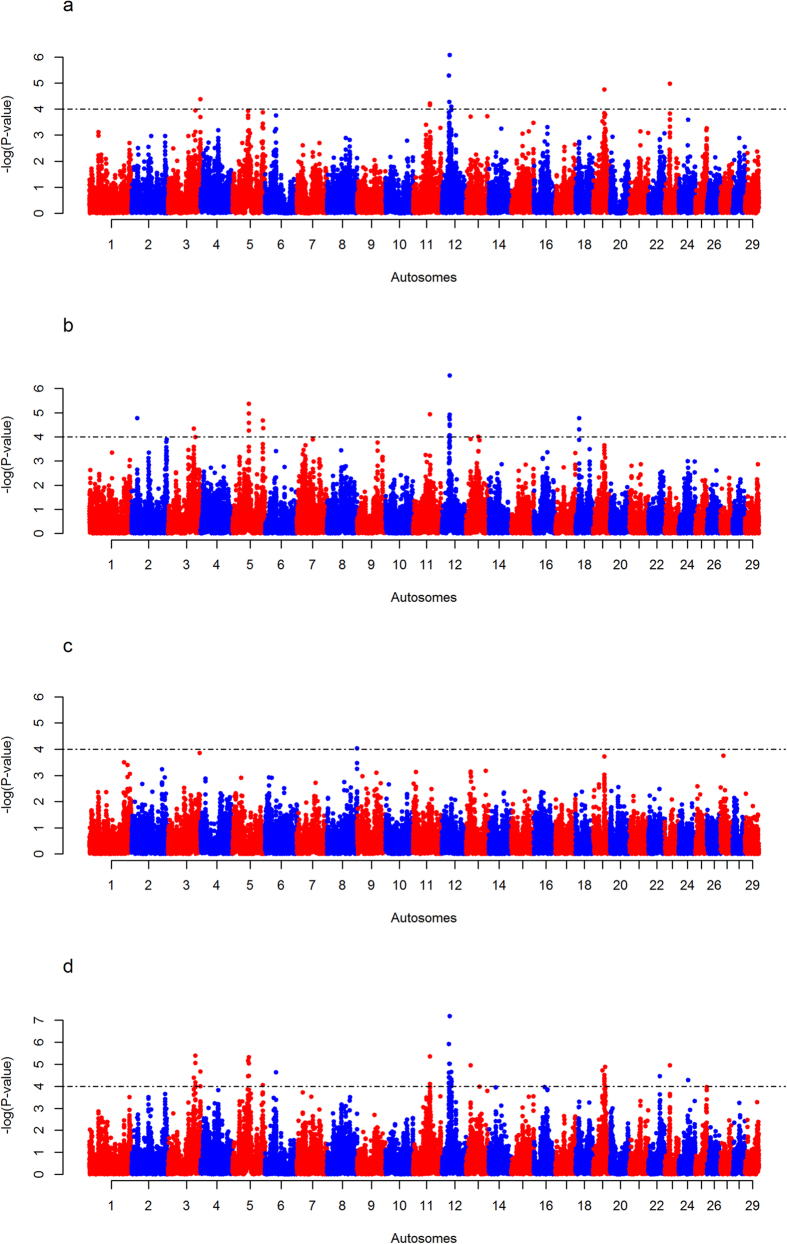

The FST analyses identifies 13 regions that might be subjected to diversifying selective pressures between EASZ and the different reference populations: one on BTA 2; two on BTA 4; one on BTA 7; two on BTA 13; one on BTA 14, BTA 19, BTA 22, BTA 24 and three on BTA X (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). iHS analysis on EASZ indicates three candidate regions on BTA 5, 23 and 29 (Fig. 3 and Table 1). These regions contain SNPs with significantly differentiated EHH between the two alleles (ancestral and derived). The Rsb analysis between EASZ and the combined reference populations reveals eight candidate genomic regions with differential EHHS: one on BTA 3, two on BTA 5, one on BTA 11, three on BTA 12, one on BTA 19 (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Six of these eight candidate regions show significant SNPs in the European taurine and/or African taurine pairwise Rsb analyses (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S1). In total 24 candidate regions under positive selection on 14 autosomes and BTA X (three regions) are identified in the genome of EASZ (Table 1).

Figure 1. Manhattan plots of the pairwise genome-wide autosomal FST analyses.

(A) EASZ with European taurine (Holstein-Friesian, Jersey), (B) EASZ with African taurine (N’Dama), and (C) EASZ with Asian zebu (Nellore). The significant thresholds (dashed line) are set at the top 0.2% of the FST distribution.

Figure 2. Manhattan plots of the pairwise BTA X FST analyses.

(A) EASZ with European taurine (Holstein-Friesian, Jersey), (B) EASZ with African taurine (N’Dama), and (C) EASZ with Asian zebu (Nellore). The significant threshold (dashed line) is set at the top 3% of the FST distribution.

Table 1. Candidate regions for signature of positive selection in EASZ.

| BTA | Position of most significant SNPs (bp) | Candidate region intervals (bp) | Candidate genes | Test | Ref | Median ΔAZ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 125,585,810 | 125,585,810 – 126,058,677 | Uncharacterised | Fst | 16 | −0.003 |

| 3 | 101,942,771 | 101,442,771 – 102,442,771 | TMEM53 | Rsb | 16 | −0.132 |

| C1orf228 | 19 | |||||

| RNF220 | ||||||

| 4 | 47,216,521 | 47,195,467 – 47,539,595 | ATXN7L1 | Fst | 16 | 0.016 |

| 19 | ||||||

| 42 | ||||||

| 4 | 52,138,962 | 51,927,595 – 52,308,430 | _ | Fst | 19 | −0.051 |

| 42 | ||||||

| 44** | ||||||

| 45** | ||||||

| 5 | 57,977,594 | 57,477,594 – 58,477,594 | OR6C4 | Rsb | 19 | −0.003 |

| OR2AP1 | 18 | |||||

| 43** | ||||||

| 5 | 60,556,520 | 60,056,520 – 61,056,520 | SNRPF | Rsb | 19 | 0.049 |

| CCDC38 | 16 | |||||

| 18 | ||||||

| 5 | 76,286,670 | 75,786,670 – 76,786,670 | CARD10 MFNG | iHs | 0.043 | |

| 7 | 52,419,683 | 52,224,595 – 52,720,797 | UBE2D2 | Fst | 19 | 0.07 |

| 11 | 62,629,106 | 62,129,106 – 63,129,106 | _ | Rsb | 0.008 | |

| 12 | 27,181,474 | 26,681,474 – 27,681,474 | _ | Rsb | 19 | −0.188 |

| 12 | 29,217,254 | 28,717,254 – 29,717,254 | RXFP2 | Rsb | 19 | −0.038 |

| 16 | ||||||

| 17 | ||||||

| 12 | 35,740,174 | 35,240,174 – 36,240,174 | EFHA1 | Rsb | −0.084 | |

| 13 | 46,472,930 | 46,433,697 – 46,723,493 | ADARB2 | Fst | 18 | 0.022 |

| Uncharacterised | ||||||

| 13 | 58,099,969 | 57,848,276 – 58,207,174 | bta-mir-296 | Fst | 18 | 0.051 |

| 43** | ||||||

| 14 | 24,437,778 | 24,482,969 – 25,254,540 | XKR4 | Fst | 43** | −0.042 |

| 46 | ||||||

| 19 | 27,444,684 | 27,369,763 – 27,763,447 | ALOX12 | Fst | 19 | −0.012 |

| RNASEK | ||||||

| BAP18 | ||||||

| BCL6B | ||||||

| SLC16A13 | ||||||

| SLC16A11 | ||||||

| CLEC10A | ||||||

| 19 | 42,696,815 | 42,196,815 – 43,196,815 | KLHL10 | Rsb | 42 | −0.004 |

| KLHL11 | ||||||

| ACLY | ||||||

| 22 | 2,655,659 | 2,314,019 – 2,788,566 | – | Fst | 0.035 | |

| 23 | 28,281,915 | 27,781,915 – 28,781,915 | TRIM39-RPP21 | iHs | 19 | –0.004 |

| LOC512672 | 18 | |||||

| uncharacterised | ||||||

| 24 | 4,461,406 | 4,118,163 – 4,474,760 | CYB5A | Fst | 0.006 | |

| 29 | 1,898,171 | 1,398,171 – 2,398,171 | Uncharacterized | iHs | 18 | 0.022 |

| X | 9,201,028 | 8,582,093 – 9,248,137 | bta-mir-2483 | Fst | −0.113 | |

| X | 40,738,704 | 39,942,044 – 43,999,854 | Metazoa_SRP | Fst | 46 | −0.05 |

| X | 85,589,749 | 84,566,018 – 85,993,719 | DGAT2L6 | Fst | 46 | −0.034 |

| IGBP1 |

Ref: Reference number for previous studies reporting overlapping regions with the identified candidate regions. **Commercial breeds studies. ΔAZ: The average excess/deficiency in Asian zebu ancestry at each SNP calculated by subtracting the average estimated Asian zebu ancestry of the SNP from the average estimated Asian zebu ancestry of all SNPs. Bold (deviation by plus or minus 1 s.d. from the genome-wide mean ΔAZ).

Figure 3. Manhattan plots of the genome-wide iHS analysis on EASZ, applied to a two-tailed Z-test.

The plot in (A) shows the autosomal analysis, whilst (B) shows the BTA X analysis. The significance threshold (dashed line) is set at −log10 (two-tailed P-value) of 4.

Figure 4. Manhattan plots of the genome-wide autosomal Rsb analyses.

(A) EASZ with European taurine (Holstein-Friesian, Jersey), (B) EASZ with African taurine (N’Dama), (C) EASZ with Asian zebu (Nellore), and (D) EASZ with all reference populations (Holstein-Friesian, Jersey, N’Dama and Nellore) combined applied to one-tailed Z-tests. The significant thresholds (dashed line) is set at −log10 one-tailed P-value = 4.

Estimation of excess - deficiency of Asian zebu ancestry at the candidate regions

The mean and median ΔAZ for all SNPs in EASZ are 0 and 0.018 ± 0.07 (s.d.) for autosomes, and 0 and 0.04 ± 0.05 (s.d.) for BTA X, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). Ten regions show excess (positive ΔAZ values) and 14 regions show deficiency (negative ΔAZ values) in zebu ancestry (Table 1). They include six regions with a ΔAZ at least more than one standard deviation higher or lower from the mean (five regions with deficiency and one region with excess) (Table 1).

Overlaps between candidate genome regions in EASZ, others cattle studies and bovine QTL

Among the 24 candidate regions for positive selection, 18 were previously identified in other tropical cattle populations and 4 in commercial breeds (Table 1). Six candidate regions are reported for the first time in a cattle population, including 4 regions on autosomes (BTA 5, BTA 11, BTA12 and BTA 1 3) and two on BTA X.

A total of 340 bovine QTL intersect with the identified candidate regions (Supplementary Table S3). These QTL are associated with different biological pathways linked to local African environment adaptation, such as parasite vector resistance (e.g. tick resistance QTL), fertility (e.g. male fertility QTL and sperm motility QTL), feeding (e.g. residual feed intake QTL), and coat colour QTL. Interestingly, several intersecting QTL are associated with different productivity traits usually favoured in commercial breeds, e.g. milk fat yield, marbling score QTL and longissimus muscle area QTL (Supplementary Table S3).

Identification of candidate genes

Within the candidate region intervals obtained from the inter-population FST analysis and the two EHH-based analyses (iHS and Rsb), a total of 192, 72 and 145 genes are identified, respectively (Supplementary Table S4). These 409 genes grouped into 53 functional term clusters. Five of these clusters are significantly enriched (enrichment score more than 1.3, P-value < 0.05) relative to the whole bovine genome (Table 2). These include enriched clusters associated with keratin structure, innate and acquired immunity, and growth and steroid hormone signalling. Considering only genes within 25 kb of the most significant SNPs reduces the number of genes to 37 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S5). Following DAVID analysis, these candidates form two non-significantly enriched functional term clusters: transmembrane region (enrichment score = 0.95) and ion binding (enrichment score = 0.46).

Table 2. Significant enriched functional term clusters of genes within candidate region intervals.

| Functional term cluster | Enrichment score |

|---|---|

| Intermediate protein filaments and keratin | 2.11 |

| Immune response and antigen processing and presenting | 1.88 |

| Ribosome structure | 1.62 |

| Regulation of cells adhesion and mammary gland development | 1.55 |

| Regulation of steroid and growth hormone signaling pathway | 1.53 |

The candidate genome regions with deficiency or excess of zebu ancestry also harbour interesting genes. The five regions with zebu ancestry deficiency (Table 1) carry genes involved in acquired immune response (e.g. IL17D and IRAK1), mRNA processing regulation (e.g. U5 and U6), and cell cycle regulation (HECTD3). Moreover, the candidate region on BTA 7, which shows an excess in zebu ancestry, contains genes associated with critical biological pathways suggested to be under selection in tropical adapted cattle17, such as protein folding and heat shock response (DNAJC7), and male reproduction (SPATA24).

Discussion

In this study, we used three analyses (intra-population (iHS), inter-population Rsb, and FST) with the aim to identify candidate signatures of positive selection in the genome of an indigenous East African cattle population. We pooled all the non-admixed cattle populations into a single reference population in Rsb. As shown in Fig. 4, the pooling approach has made the signals of selection in the Rsb-specific candidate regions stronger in comparison to their signals in the pairwise analyses. This might be due to a reduction of the effect of population-specific LD caused by genetic drift. Such an empirical haplotype pooling approach has been suggested previously by Gautier and Naves16.

None of the results were found to overlap between the three analyses. The lack of overlap between iHS and Rsb analyses may be explained by the reduced power of iHS to detect regions where alleles have almost reached fixation. Moreover, candidate genome regions identified by iHS may not be detected by Rsb if the favourable alleles/haplotypes have also been subjected to selection in the reference population. Absence of overlaps between Rsb and FST analyses is likely a consequence of the selection time-scale with Rsb being more suitable for detecting signatures of recent selection39. Importantly, the results described here were obtained through the analysis of Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip v.1 genotyping data. Given the genome coverage and the ascertainment bias of the tool towards European taurine breeds23, it is possible that some important genome regions might not have been identified. The use of higher density SNP array and/or full genome information may address these issues to some extent.

In the context of our understanding of the history of African zebu cattle, which has witnessed founding events and introgression1, the pattern of EASZ genome diversity was also likely influenced by demographic events. Distinguishing between the effects of natural selection and demographic events on the genome is difficult40,41. Moreover, the issue of the SNP chip ascertainment bias might have led to lower SNP diversity, and hence increased haplotype homozygosity, in zebu cattle in comparison to European taurine breeds23.

The majority (18 out of 24, Table 1) of our candidate regions for positive selection overlap with previously identified regions. These 18 candidate genome regions have been previously identified in other tropical adapted cattle populations such as taurine and admixed West African cattle18,19, the admixed Caribbean Creole16 or the Brahman zebu cattle42 (Table 1). Also, four of these regions have been shown to be under positive selection in beef and dairy commercial breeds (Charolais, Murray Grey and Shorthorn cattle43, Holstein44 and Fleckvieh cattle45) (Table 1), and/or are overlapping with production QTL (Supplementary Table S3). Assuming that the same selective forces were acting across these populations, it provides support that the pattern of genetic diversity and linkage disequilibrium observed at these regions has been shaped by selection rather than genetic drift and/or admixture. This is of particular relevance for our comparisons across cattle populations living within the tropics, which are exposed to somewhat similar environmental challenges (e.g. high temperatures). Moreover, while we cannot exclude that EASZ might have been selected in the past for production traits, this remains hypothetical. Indeed, EASZ are not recognized as milk or beef breeds, but they are commonly used for milk, ploughing and exchange for cash7. Here, positive selection on genes with pleiotropic effect and/or linkage disequilibrium between loci involved in different metabolic pathways, rather than a common selection pressure, might explain the overlapping candidate genome regions observed between EASZ and commercial breeds.

We detected excesses - deficiencies of Asian zebu ancestry at several of the identified candidate regions further supporting the role of selection (Table 1). More specifically, the candidate region in BTA 7 has the highest excess of zebu ancestry. As expected this region shows genetic differentiation when EASZ is compared to European taurine and N’Dama cattle but not to Nellore (Supplementary Table S1). Also, an overlapping region has been found to be highly differentiated between zebu and taurine cattle in Porto-Neto et al.46, further supporting its zebu origin. The candidate region showing the highest excess of taurine ancestry was found on BTA 12, in a region also identified as positively selected in West African cattle19. Given the low overall African taurine ancestry proportion in the EASZ genome13 (Supplementary Table S2), the presence of “zebu deficient” regions, likely a consequence of selection in favour of taurine-specific alleles, are of a particular interest.

The biological pathways, genes and QTL identified within the candidate regions further allows to classify the diversity of selective forces having shaped the genome of EASZ. These forces might be associated with the African tropical environment (e.g. immune pathways, reproduction and fertility pathway), the admixed zebu x taurine genome structure of EASZ (e.g. development and growth pathways) and human selection for specific traits.

Several of the candidate genes further support the presence of distinct selective forces (Table S5). Some of these genes are involved in regulating innate and adaptive immunity in mammals (LOC512672 on BTA 23, IGBP1 on BTA X and BCL6B on BTA 19). For example, LOC512672 is a major histocompatibility complex class I gene. This class of genes is responsible for presenting antigen peptides to cytotoxic T-cells to induce their immunological response47. These results suggest that immunity genes are hot spots of natural selection in EASZ in response to the high pathogen challenge in their local environment10,11,48.

Candidate genes associated with male reproduction (OR2AP1, OR6C4, RXFP2, KLHL10) have also been identified within candidate regions on BTA 5, 12 and 19. These genes may be associated to superior fertility and semen quality in zebu cattle under heat stress conditions compared to exotic taurine12. RXFP2 is located within the most significant Rsb candidate genomic region in BTA 12. The protein encoded by this gene is involved in the testicular descent development49,50, which is an adaptation to maintain proper spermatogenesis when the core body temperature reaches 34°–35 °C51. Interestingly, the genome region harbouring RXFP2 has also been identified to be under positive selection in tropically adapted Creole cattle16 and West African admixed Borgou cattle18. This gene has also been linked to Soay sheep reproductive success and survival rate52 as well as to sheep horn development53. The two olfactory receptor candidate genes (OR6C4 and OR2AP1) identified in BTA 5 can be classified as male reproduction genes. These genes may play a role in guiding sperms towards oocyte during fertilization via the interaction with various chemoattractants secreted by the oocyte-cumulus cells complex54.

Also an interesting candidate gene identified in BTA 19 is ACLY. This gene encodes an enzyme involves in energy production by linking glucose metabolism to lipid synthesis55. This biological pathway is critical in EASZ to maintain adequate energy production and activity in their harsh environment.

Several genes identified within the candidate region intervals, but not considered as candidate genes following our criteria of presence within 25 kb of the most significant SNP, are also associated with various biological functions that might be under selection in African cattle. Due to the utilisation of Kenyan zebu cattle in ploughing and transportation by farmers7, genes related to skeletal muscle function and structure might have been the target of human-driven selection. Within the candidate regions on BTA 5, members of the myosin light chain genes family (MYL6 and MYL6B) and SYT10 belong to this category.

Climate stress (e.g. temperature, humidity, UV) is expected to be an important selection pressure acting on EASZ. Several genes associated with the heat shock protein family (HSPB9, DNAJC7, DNAJC8, DNAJC14 and DNAJC18), or associated with the heat stress response (PPP1R10)56 have been identified within the candidate region intervals on BTA 5, 7, 19 and 23. Interestingly, Gautier and Naves16 detected another PPP1 regulatory subunit (PPP1R8) in a positively selected genomic region in the Creole cattle. Also, several coat colour QTL overlap with a candidate region in BTA 5. Brown coats are predominant in EASZ57 and may have been selected for natural, in relation to thermoregulation, or be the result of human-mediated selection. Within candidate regions in BTA 5 and 19 several genes related to hair structure and coat colour were identified (KRT and PMEL17)58,59,60. Genes in this functional category may be subjected to positive selection due to the association of these two characteristics with tick resistance and thermotolerance61,62.

In conclusion, we report here for the first time the identification of candidate regions for signatures of positive selection in the genome of an indigenous East African cattle population. We show that a diversity of selection pressures has likely shaped the genome of this population. Given its long history of zebu – taurine admixture, this population represents an important model for the understanding of the effect of different selective factors on the genome diversity of indigenous tropical admixed cattle. This is of particular relevance in a context of changing agricultural production systems and practices witnessed across the African continent. Increasingly indigenous zebu cattle are being crossed with exotic taurine in an attempt to improve their productivities. The result is often more productive but poorly adapted animals. The identification of these candidate positive signatures of selection is paving the way to inform crossbreeding where the emphasis is towards introgression of production traits as well as on maintaining key adaptations for survival in challenging environments.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Bahbahani, H. et al. Signatures of positive selection in East African Shorthorn Zebu: A genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Sci. Rep. 5, 11729; doi: 10.1038/srep11729 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the Wellcome Trust (grant reference 07995) for financially supporting this project. To USDA-ARS bovine functional laboratory and GeneSeek veterinary diagnostics for providing invaluable technical assistance through the genotyping of the samples. We also would like to thank the entire IDEAL project team for their highly appreciated efforts. The first author is financially supported by a PhD scholarship from Kuwait University. Finally, we wish to acknowledge the grass root farmers of Western Kenya who participated fully and made this project a success.

Footnotes

Author Contributions H.B., H.C., M.W. and O.H. conceived, designed the experiment. H.B, H.C. and O.H. performed the experiment. H.B. and H.C. analysed the data. D.W., T.S., M.N.M., M.W. and C.V.T. contributed data and/or analysis tools. H.B., H.C. and O.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors have agreed on the content of the manuscript.

References

- Hanotte O. et al. African pastoralism: genetic imprints of origins and migrations. Science 296, 336–339 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. et al. Zebu cattle are an exclusive legacy of the South Asia neolithic. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 1–6 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy C. S. et al. Genetic evidence for Near-Eastern origins of European cattle. Nature 410, 1088–1091 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker J. E. et al. Worldwide patterns of ancestry, divergence, and admixture in domesticated cattle. PLoS Genetics 10, e1004254; 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004254 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford-Gonzalez D. & Hanotte O. Domesticating Animals in Africa: Implications of Genetic and Archaeological Findings. Journal of World Prehistory 24, 1–23 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D. G., MacHugh D. E., Cunningham P. & Loftus R. T. Mitochondrial diversity and the origins of African and European cattle. PNAS 93, 5131–5135 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rege J. E. O., Kahi A. M. O. A., Mwacharo J. & Hanotte O. Zebu Cattle of Kenya: Uses, Performance, Farmer Preferences and Measures of Genetic Diversity [21–38] (International Livestock Reaserch Institute, Nairobi, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Latif A. A., Nokoe S., Punyua D. K. & Capstick P. B. Tick infestations on Zebu cattle in western Kenya: quantitative assessment of host resistance. J. Med. Entomol. 28, 122–126 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock R., Jackson L., Ds Vos A. & Jorgensen W. Babesiosis of cattle. Parasitology 129, S247–S269 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clare Bronsvoort B. M. et al. Design and descriptive epidemiology of the Infectious Diseases of East African Livestock (IDEAL) project, a longitudinal calf cohort study in western Kenya. BMC Vet. Res. 9, 171–192 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thumbi S. M. et al. Parasite co-infections and their impact on survival of indigenous cattle. PloS one 9, e76324; 10.1371/journal.pone.0076324 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen P. J. Physiological and cellular adaptations of zebu cattle to thermal stress. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 82-83, 349–360 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbole-Kariuki M. N. et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals the ancient and recent admixture history of East African Shorthorn Zebu from Western Kenya. Heredity 113, 297–305 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray G. G. et al. Genetic susceptibility to infectious disease in East African Shorthorn Zebu: a genome-wide analysis of the effect of heterozygosity and exotic introgression. BMC Evol. Biol. 13, 246–253 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kijas J. W. et al. Genome-wide analysis of the world's sheep breeds reveals high levels of historic mixture and strong recent selection. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001258; 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001258 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier M. & Naves M. Footprints of selection in the ancestral admixture of a New World Creole cattle breed. Mol. Ecol. 20, 3128–3143 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Li X., Li K., Fan B. & Tang Z. A genome-wide scan for signatures of selection in Chinese indigenous and commercial pig breeds. BMC Genet. 15, 7–15 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flori L. et al. Adaptive admixture in the West African bovine hybrid zone: insight from the Borgou population. Mol. Ecol. 23, 3241–3257 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier M. et al. A whole genome Bayesian scan for adaptive genetic divergence in West African cattle. BMC Genomics 10, 550; 10.1186/1471-2164-10-550 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L. et al. Genomic signatures reveal new evidences for selection of important traits in domestic cattle. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 711–725 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flori L. et al. A quasi-exclusive European ancestry in the Senepol tropical cattle breed highlights the importance of the slick locus in tropical adaptation. PloS one 7, e36133; 10.1371/journal.pone.0036133 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matukumalli L. K. et al. Development and characterization of a high density SNP genotyping assay for cattle. PloS one 4, e5350; 10.1371/journal.pone.0005350 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs R. A. et al. Genome-wide survey of SNP variation uncovers the genetic structure of cattle breeds. Science 324, 528–532 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aulchenko Y. S., Ripke S., Isaacs A. & van Duijn C. M. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics 23, 1294–1296 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. The genetical structure of populations Annals of Eugenics 15, 323–354 (1951). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voight B. F., Kudaravalli S., Wen X. & Pritchard J. K. A map of recent positive selection in the human genome. PLoS Biol. 4, e72; 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040072 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang K., Thornton K. R. & Stoneking M. A new approach for using genome scans to detect recent positive selection in the human genome. PLoS Biol. 5, e171; 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050171 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier M. & Vitalis R. rehh: an R package to detect footprints of selection in genome-wide SNP data from haplotype structure. Bioinformatics 28, 1176–1177 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker J. E. et al. Resolving the evolution of extant and extinct ruminants with high-throughput phylogenomics. PNAS 106, 18644–18649 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacia J. G. et al. Determination of ancestral alleles for human single-nucleotide polymorphisms using high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nature Genet. 22, 164–167 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay S. D. et al. Whole genome linkage disequilibrium maps in cattle. BMC Genet. 8, 74–85 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheet P. & Stephens M. A fast and flexible statistical model for large-scale population genotype data: applications to inferring missing genotypes and haplotypic phase. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 78, 629–644 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsunomiya Y. T. et al. Detecting loci under recent positive selection in dairy and beef cattle by combining different genome-wide scan methods. PloS one 8, e64280; 10.1371/journal.pone.0064280 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicek P. et al. Ensembl 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D48–55 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Da W., Sherman B. T. & Lempicki R. A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1–13 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard J. K., Stephens M. & Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankararaman S., Sridhar S., Kimmel G. & Halperin E. Estimating local ancestry in admixed populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82, 290–303 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keightley P. D. & Eyre-Walker A. Deleterious mutations and the evolution of sex. Science 290, 331–333 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleksyk T. K., Smith M. W. & O'Brien S. J. Genome-wide scans for footprints of natural selection. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci 365, 185–205 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akey J. M., Zhang G., Zhang K., Jin L. & Shriver M. D. Interrogating a high-density SNP map for signatures of natural selection. Genome R12, 1805–1814 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qanbari S. & Simianer H. Mapping signatures of positive selection in the genome of livestock. Livestock Science 166, 133–143 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Chan E. K., Nagaraj S. H. & Reverter, A. The evolution of tropical adaptation: comparing taurine and zebu cattle. Anim. Genet. 41, 467–477 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper K. E., Saxton S. J., Bolormaa S., Hayes B. J. & Goddard M. E. Selection for complex traits leaves little or no classic signatures of selection. BMC Genomics 15, 246–259 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin D. M. et al. Whole-genome resequencing of two elite sires for the detection of haplotypes under selection in dairy cattle. PNAS 109, 7693–7698 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qanbari S. et al. Classic selective sweeps revealed by massive sequencing in cattle. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004148; 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004148 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porto-Neto L. R. et al. Genomic divergence of zebu and taurine cattle identified through high-density SNP genotyping. BMC genomics 14, 876; 10.1186/1471-2164-14-876 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan M., Del Cid N., Rizvi S. M. & Peters L. R. MHC class I assembly: out and about. Trends Immunology 29, 436–443 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahbahani H. & Hanotte O. Genetic resistance – tolerance to vector-borne diseases, prospect and challenges of genomics. OIE Scientific and Technical Review 34, 185–197 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agoulnik A. I. Relaxin and related peptides in male reproduction. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 612, 49–64 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S. et al. INSL3/RXFP2 signaling in testicular descent. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1160, 197–204 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. I. et al. Origin of INSL3-mediated testicular descent in therian mammals. Genome Res. 18, 974–985 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston S. E. et al. Life history trade-offs at a single locus maintain sexually selected genetic variation. Nature 502, 93–95 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston S. et al. Genome-wide association mapping identifies the genetic basis of discrete and quantitative variation in sexual weaponry in a wild sheep population. Mol. Ecol. 20, 2555 - 2566 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spehr M. et al. Identification of a testicular odorant receptor mediating human sperm chemotaxis. Science 299, 2054–2058 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srere P. A. The citrate cleavage enzyme. I. Distribution and purification. J. Biol. Chem. 234, 2544–2547 (1959). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. & Manley J. L. A complex signaling pathway regulates SRp38 phosphorylation and pre-mRNA splicing in response to heat shock. Mol. Cell 28, 79–90 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbole-Kariuki M. N. Genomic diversity of East African shorthorn Zebu of western Kenya. PhD thesis, University of Nottingham (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Theos A. C., Truschel S. T., Raposo G. & Marks M. S. The Silver locus product Pmel17/gp100/Silv/ME20: controversial in name and in function. Pigment cell Res. 18, 322–336 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunberg E. et al. A missense mutation in PMEL17 is associated with the Silver coat color in the horse. BMC Genet. 7, 46–56 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L. H. & Coulombe P. A. Keratin function in skin epithelia: a broadening palette with surprising shades. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 13–23 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez M. L. et al. Association of BoLA-DRB3.2 alleles with tick (Boophilus microplus) resistance in cattle. Genet. Mol. Res. 5, 513–524 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikmen S. et al. Differences in thermoregulatory ability between slick-haired and wild-type lactating Holstein cows in response to acute heat stress. J. Dairy Sci. 91, 3395–3402 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.