Abstract

Objectives

Social deprivation impacts on healthcare outcomes but is not included in the majority of cardiac surgery risk prediction models. The objective was to investigate geographical variations in social deprivation of patients undergoing cardiac surgery and identify whether social deprivation is an independent predictor of outcomes.

Methods

National Adult Cardiac Surgery Audit data for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), or valve surgery performed in England between April 2003 and March 2013, were analysed. Base hospitals in England were divided into geographical regions. Social deprivation was measured by quintile groups of the index of multiple deprivation (IMD) score with the first quintile group (Q1) being the least, and the last quintile group (Q5) the most deprived group. In-hospital mortality and midterm survival were analysed using mixed effects logistic, and stratified Cox proportional hazards regression models respectively.

Results

240 221 operations were analysed. There was substantial regional variation in social deprivation with the proportion of patients in IMD Q5 ranging from 34.5% in the North East to 6.5% in the East of England. Following adjustment for preoperative risk factors, patients undergoing all cardiac surgery in IMD Q5 were found to have an increased risk of in-hospital mortality relative to IMD Q1 (OR=1.13; 95%CI 1.03 to 1.24), as were patients undergoing isolated CABG (OR=1.19; 95%CI 1.03 to 1.37). For midterm survival, patients in IMD Q5 had an increased hazard in all groups (HRs ranged between 1.10 (valve+CABG) and 1.26 (isolated CABG)). For isolated CABG, the median postoperative length of stay was 6 and 7 days, respectively, for IMD Q1–Q4 and Q5.

Conclusions

Significant regional variation exists in the social deprivation of patients undergoing cardiac surgery in England. Social deprivation is associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality and reduced midterm survival. These findings have implications for health service provision, risk prediction models and analyses of surgical outcomes.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There is some evidence that social deprivation may influence outcomes following cardiac surgery, but specific measures of social deprivation are generally not considered in cardiac surgery risk modelling or outcome analyses.

A large national registry of nearly a quarter of a million patients undergoing cardiac surgery over a 10-year period is analysed with respect to social deprivation for the first time.

Results show an adverse association between increasing social deprivation and poorer outcomes following cardiac surgery.

Data on the cause of death was unavailable, meaning it is not possible to comment on mode of death, and how this may have been influenced by environmental factors, obesity, diabetes, smoking or access to healthcare.

Introduction

Social deprivation has been described as an important variable influencing outcomes in cardiovascular disease with more socially deprived populations having a significantly lower life expectancy.1–3 Despite some evidence that social deprivation may influence outcomes following cardiac surgery, specific measures of social deprivation are absent from the majority of risk-scoring models applied to cardiac surgery.

The levels of social deprivation in subpopulations served by different centres have not been previously described in a national study covering England. A large population study looking at social deprivation involving five cardiac centres pointed towards an important influence of social deprivation on outcomes after cardiac surgery.4 The aim of this study was therefore to determine whether geographical variations exist in the social deprivation of patients undergoing cardiac surgery in England, and to investigate whether social deprivation influences outcomes following cardiac surgery.

Methods

Data

Prospectively collected data were extracted from The National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR) National Adult Cardiac Surgery Audit (NACSA) registry on 14 January 2014 for adult cardiac surgery procedures performed in the UK. As described elsewhere, reproducible algorithms were applied to the database in order to clean the data.5 Records were included if they corresponded to elective or urgent coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, and/or valve surgery performed in England between 1 April 2003 and 31 March 2013. Records were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) surgery at a private hospital; (2) use of preoperative mechanical ventilation or assist device; (3) within-study redo surgery; (4) missing Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score; (5) IMD score recorded as zero and (6) missing primary outcome data.

Study variables

Each operation was recorded as (1) CABG, (2) valve surgery or (3) valve+CABG surgery. The logistic EuroSCORE was calculated for each record.6 Variable definitions are available at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/nicor/audits/adultcardiac/datasets. Data were also extracted for the non-EuroSCORE risk factors of body mass index (BMI) and smoking history (current/ex-smoker or never smoked). Missing categorical or dichotomous variable data were imputed with the mode with missing continuous variables data imputed with the median.

The IMD score is a calculated deprivation score for a geographical area inhabited by at least 1000 people. The IMD is based on income deprivation; employment deprivation; health deprivation and disability; education, skills and training deprivation; barriers to housing and services; crime and disorder; and living environment and is an established score for investigating social deprivation and cardiovascular disease outcome.7 For this study, the individual components of the IMD score were not available. The overall IMD score was grouped into five equal-sized groups using the quintiles as thresholds, with quintile group one (Q1) being the least deprived group and quintile group five (Q5) the most deprived group. Patients were assigned to a geographical region in England based on the location of the base hospital, not private residency.

Outcome variables

The primary outcomes were in-hospital mortality and midterm survival. The secondary outcome was prolonged postoperative length of stay (PLOS) which was defined as >14 days hospital stay following the index operation, regardless of whether the patient was discharged alive or dead. This adverse outcome is a routine quality measurement applied by the US Society of Thoracic Surgeons.8 Patients who died in-hospital on the day of surgery were recorded as having a nominal survival time/PLOS of 0.5 days. Postdischarge survival data was collected by linking patient NHS numbers to the National Health Service Central Register. The last date of census was 30 July 2013. PLOS data was compared on a case-complete basis.

Statistical analysis

To assess whether social deprivation is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality, multiple logistic mixed-effects regression models were fit for the complete data set (‘all cardiac surgery’) and each operation subgroup. IMD quintile groups, logistic EuroSCORE, BMI and smoking history were included as independent variables. The logistic EuroSCORE was included in the in-hospital mortality model through a logit (log-odds) transformation. BMI was included in the model using restricted cubic spline functions on 5 knots.9 Other parameterisations of BMI were examined without any considerable change in inferences. As patients in the same hospital are likely to be clustered, the operating hospital was included using a random intercepts model. The integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) between models with and without IMD quintile was calculated, and whether the measure was statistically different from zero was tested.10

Midterm survival data are presented as unadjusted Kaplan–Meier graphs stratified by IMD quintile and compared using the log-rank test. To assess whether social deprivation is independently associated with midterm survival, Cox proportional hazards regression models were fit for the complete data set, and each operation subgroup with the baseline hazards function stratified on hospital. IMD quintile groups, BMI, logistic EuroSCORE and smoking history were included as independent variables. BMI was included as per the in-hospital mortality analysis. The logistic EuroSCORE was included in the model using restricted cubic spline functions applied to the a priori natural logarithm transformation with 4 knots.

The proportional hazards assumption for IMD quintile was assessed by means of plotting the complimentary log-log function for the Kaplan–Meier prior to model fitting. Following regression, the Grambsh and Therneau test11 was used to assess each variable individually for evidence of proportional hazards assumption violation. Smoking status violated the proportional hazards assumption so the baseline hazards were further stratified on this variable.

As EuroSCORE and BMI are only used for adjustment purposes, the associated effect sizes for these variables have not been reported. To assess whether any potential differential effects from patient and operative risk factors was masked by the composite logistic EuroSCORE, the Cox proportional hazards regression model was refitted for the all-cardiac surgery data with the constituent risk factors of the EuroSCORE.

Risk-adjusted prolonged PLOS was compared between IMD quintile groups using a mixed effects logistic regression model with the same adjustment terms as per the in-hospital model. All CIs reported in this study are approximate 95% intervals calculated as ±2 SE. All analyses were performed in R V.3.0.2.12 Logistic mixed effects models were fitted using the lme4 package (V.1.0–5), and survival models were fitted using the survival package (V.2.37–4).13 14 In all cases, a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

There were 263 125 patient records identified for the study period, of which 9161 (3.5%) met exclusion criteria 1–3. A further 13 621 records (5.4%) were excluded due to missing IMD score, and 122 (0.1%) were excluded due to missing primary outcome data. The final cohort included 240 221 records from 31 hospitals, of which 156 498 (65.1%) underwent isolated CABG, 50 960 (21.2%) underwent isolated valve surgery, and 32 763 (13.6%) underwent valve+CABG surgery. All data were missing in <2.0% of records except for BMI (2.3% of records); serum creatinine (5.0%); active infective endocarditis (2.8%); and pulmonary hypertension (7.0%).

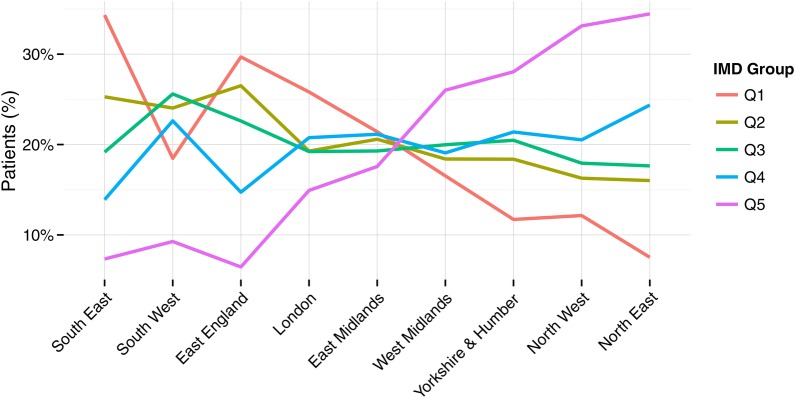

IMD score quintile groups were defined as follows: Q1 (IMD <8.53; n=48 095); Q2 (8.53≤ IMD <13.56; n=48 061); Q3 (13.56≤ IMD <20.45; n=48 011); Q4 (20.45≤ IMD <33.05; n=48 017) and Q5 (IMD ≥33.05; n=48 037). There was substantial hospital-level geographical variation in the IMD scores of patients undergoing cardiac surgery as shown in figure 1. The proportion of patients in IMD Q5 ranged from 34.5% in the North East of England hospitals to 6.5% in East England hospitals. Summary statistics for logistic EuroSCORE, BMI, smoking history and IMD quintile by surgery group are shown in table 1. An increase in both BMI and the proportion of patients with a smoking history with increasing IMD quintile was observed.

Figure 1.

The proportion of patients undergoing all-cardiac surgery in each index of multiple deprivation (IMD) quintile group by geographical area.

Table 1.

Summary of patient data included in regression models by IMD quintile group and operation type

| IMD quintile group | Number | Logistic EuroSCORE |

BMI |

Smoking history |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | N | Per cent | ||

| All cardiac surgery | |||||||

| Q1 | 48 095 | 5.64 | 6.71 | 27.61 | 4.43 | 29 210 | 60.73 |

| Q2 | 48 061 | 5.56 | 6.62 | 27.94 | 4.46 | 30 577 | 63.62 |

| Q3 | 48 011 | 5.52 | 6.73 | 28.14 | 4.64 | 31 335 | 65.27 |

| Q4 | 48 017 | 5.42 | 6.65 | 28.33 | 4.79 | 32 761 | 68.23 |

| Q5 | 48 037 | 5.43 | 6.87 | 28.61 | 5.05 | 34 700 | 72.24 |

| CABG alone | |||||||

| Q1 | 29 739 | 4.02 | 4.94 | 27.99 | 4.21 | 19 422 | 65.31 |

| Q2 | 30 466 | 4.04 | 4.97 | 28.25 | 4.26 | 20 776 | 68.19 |

| Q3 | 30 828 | 4.07 | 5.15 | 28.46 | 4.42 | 21 495 | 69.73 |

| Q4 | 32 266 | 4.09 | 5.20 | 28.62 | 4.58 | 23 273 | 72.13 |

| Q5 | 33 199 | 4.18 | 5.50 | 28.87 | 4.81 | 25 107 | 75.63 |

| valve+CABG | |||||||

| Q1 | 7148 | 9.71 | 9.13 | 27.28 | 4.46 | 4374 | 61.19 |

| Q2 | 6896 | 9.55 | 9.04 | 27.64 | 4.54 | 4401 | 63.82 |

| Q3 | 6796 | 9.45 | 9.14 | 27.72 | 4.67 | 4474 | 65.83 |

| Q4 | 6289 | 9.58 | 9.22 | 27.93 | 4.81 | 4223 | 67.15 |

| Q5 | 5634 | 9.70 | 9.49 | 28.26 | 5.07 | 4081 | 72.44 |

| Valve alone | |||||||

| Q1 | 11 208 | 7.32 | 7.42 | 26.84 | 4.83 | 5414 | 48.30 |

| Q2 | 10 699 | 7.31 | 7.35 | 27.25 | 4.83 | 5400 | 50.47 |

| Q3 | 10 387 | 7.27 | 7.50 | 27.46 | 5.15 | 5366 | 51.66 |

| Q4 | 9462 | 7.19 | 7.42 | 27.63 | 5.38 | 5265 | 55.64 |

| Q5 | 9204 | 7.30 | 7.86 | 27.88 | 5.72 | 5512 | 59.89 |

BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; IMD, index of multiple deprivation.

In-hospital mortality

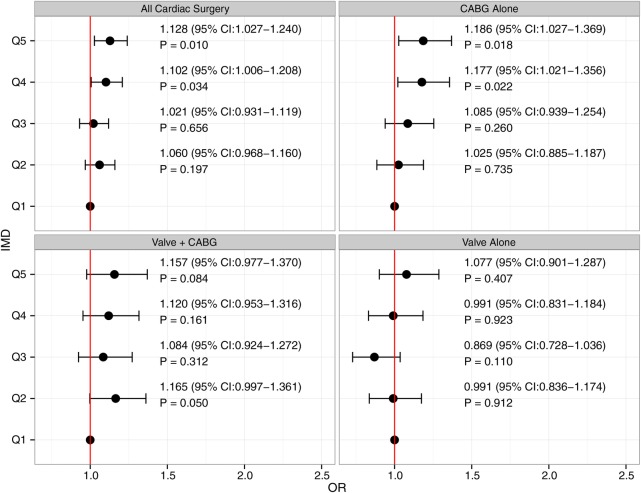

The overall in-hospital mortality was 2.3% (n=5427); 1.4% for CABG (n=2262); 2.7% (n=1397) for valve surgery; and 5.4% (n=1768) for valve and CABG surgery. The unadjusted in-hospital mortality rate for all cardiac surgery ranged from 2.2% (n=1049) in IMD Q1 to 2.4% (n=1147) in IMD Q5. Following adjustment for logistic EuroSCORE, BMI and smoking history, patients undergoing all cardiac surgery in IMD Q4–5 were at an increased risk of in-hospital mortality as shown in figure 2. The same was observed for patients undergoing isolated CABG.

Figure 2.

Estimated odds ratios for each index of multiple deprivation (IMD) quintile group (relative to IMD Q1) of in-hospital all-cause mortality (points) and 95% CIs (lines). Vertical red line denotes no effect.

For patients undergoing isolated valve surgery, or combined valve+CABG surgery, IMD quintile group was not significantly associated with in-hospital mortality. For all-cardiac surgery, isolated CABG or valve+CABG surgery the IDI was not significant (p>0.05). The IDI was marginally significant in the isolated valve surgery group (p=0.049). Overall, IDI was commensurate with increases in discrimination, measured by difference in area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, of between 0.0004 and 0.0007 when IMD quintile was included in the models.

Survival

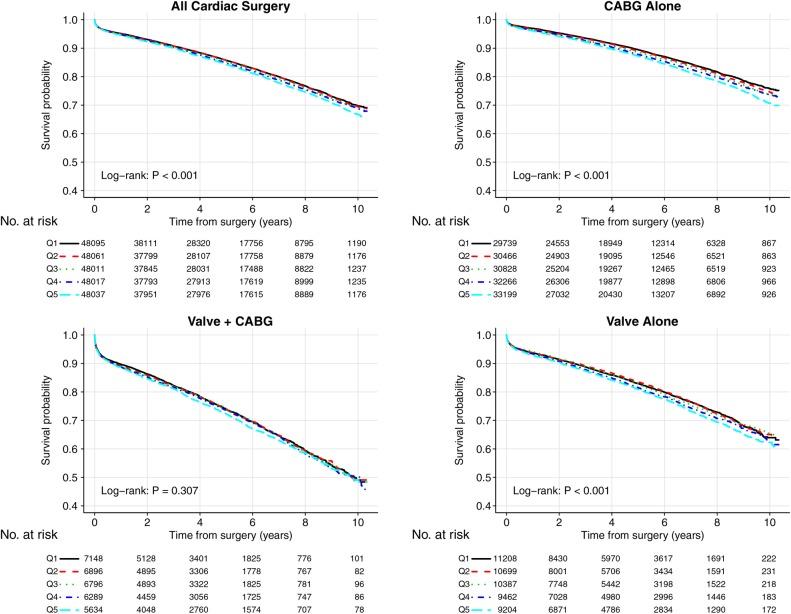

There were 1 167 090 patient-years of follow-up, with a median follow-up time of 4.8 years (range 0.5 days to 10.3 years). There were 956 (0.4%) patients only followed up to the point of discharge. The Kaplan–Meier graphs by IMD quintile group for each surgery group are shown in figure 3. Ten-year survival for all-cardiac surgery ranged from 69.8% in IMD Q1 to 66.8% in IMD Q5 (p<0.001). The largest absolute differences were observed for isolated CABG group, with 10-year survival ranging from 75.8% for IMD Q1 to 70.7% for IMD Q5 (p<0.001). For valve+CABG surgery, there was no significant difference between the IMD groups in 10-year survival (p=0.31). For isolated valve surgery, the 10-year survival estimates ranged from 63.9% for IMD Q1 to 62.3% from IMD Q5 (p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier plots for patients undergoing cardiac surgery by IMD quintile group (CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; IMD, index of multiple deprivation).

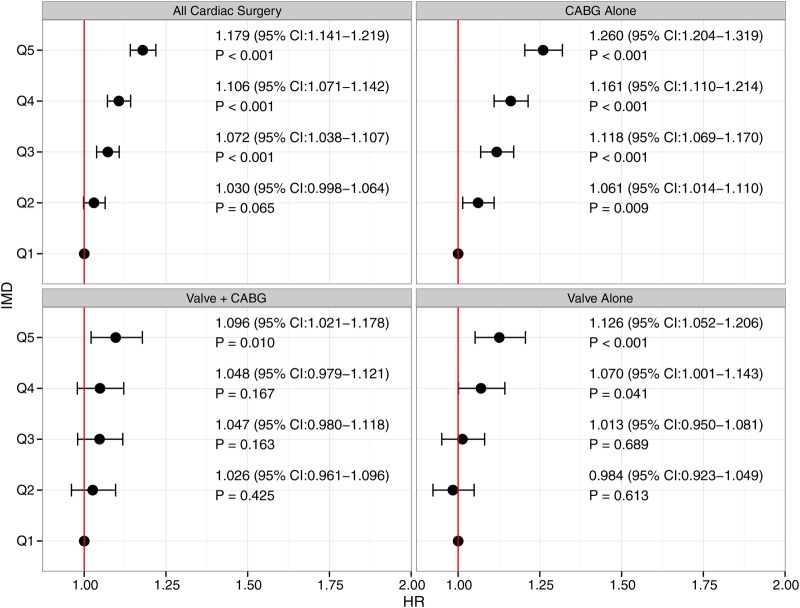

Following adjustment for logistic EuroSCORE, BMI and smoking history, the most deprived patients undergoing all-cardiac surgery in IMD Q3–5 had a significantly increased risk of reduced survival relative to IMD Q1, as shown in figure 4. Significant HRs were observed for patients in IMD Q2–5 undergoing isolated CABG, in IMD Q4–5 for isolated valve surgery, and in IMD Q5 for valve+CABG surgery. The proportional hazards assumption was not rejected in each procedure subgroup model, but for the all-cardiac surgery analysis, the proportionality assumption was rejected for one BMI spline coefficient (p=0.007) and IMD Q3 (p=0.037). Inferences about the IMD quintile effect sizes were robust to other parameterisations in BMI for this model. After refitting the model for all-cardiac surgery with the composite EuroSCORE replaced by its constituent risk factors (model coefficients not reported here), the study inferences remained unchanged, although the HRs for IMD quintile groups were consistently greater by up to 9%.

Figure 4.

Estimated hazard ratios for each IMD quintile group (relative to IMD Q1) of midterm all-cause mortality (points) and 95% CIs (lines). Vertical red line denotes no effect (CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; IMD, index of multiple deprivation).

Postoperative length of stay

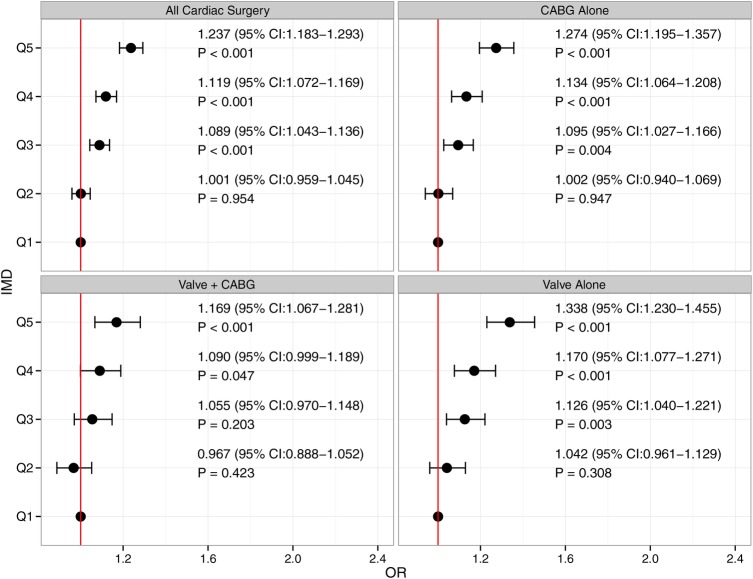

There were 5025 records with a missing PLOS data leaving a total of 235 196 records for analysis. The mean (SD) PLOS for all cardiac surgery was 9.7 (10.2) days and the median (first quartile, third quartile) PLOS was 7 (5–10) days. The average PLOS for the operation subgroups by IMD quintile are shown in table 2. Overall, 12.2% of patients had a prolonged PLOS. In the procedure subgroups it was 8.4% for CABG alone; 23.8% for CABG+valve; and 16.1% for valve surgery alone. As shown in figure 5, patients in IMD Q3–5 undergoing all-cardiac surgery, isolated CABG surgery, or isolated valve surgery had a significantly increased risk of prolonged PLOS. For patients undergoing valve+CABG surgery, patients in Q4–5 were at an increased risk of prolonged PLOS.

Table 2.

Summary statistics for PLOS data by IMD quintile group and operation type

| Number | Mean | SD | Median | (LQ, UQ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cardiac surgery | |||||

| Q1 | 47 042 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 7 | (5, 10) |

| Q2 | 47 192 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 7 | (5, 10) |

| Q3 | 47 105 | 9.6 | 10.1 | 7 | (5, 10) |

| Q4 | 46 792 | 9.8 | 10.9 | 7 | (5, 10) |

| Q5 | 47 065 | 10.1 | 11.1 | 7 | (6, 10) |

| CABG alone | |||||

| Q1 | 28 993 | 8.2 | 8.4 | 6 | (5, 8) |

| Q2 | 29 867 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 6 | (5, 8) |

| Q3 | 30 199 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 6 | (5, 8) |

| Q4 | 31 358 | 8.7 | 9.4 | 6 | (5, 9) |

| Q5 | 32 467 | 9.0 | 9.7 | 7 | (5, 9) |

| Valve+CABG | |||||

| Q1 | 7041 | 12.6 | 12.2 | 9 | (7, 14) |

| Q2 | 6788 | 12.5 | 12.6 | 9 | (7, 14) |

| Q3 | 6683 | 12.9 | 13.1 | 9 | (7, 14) |

| Q4 | 6163 | 13.5 | 15.4 | 9 | (7, 14) |

| Q5 | 5546 | 14.0 | 15.1 | 9 | (7, 15) |

| Valve alone | |||||

| Q1 | 11 008 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 8 | (6, 11) |

| Q2 | 10 537 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 8 | (6, 11) |

| Q3 | 10 223 | 10.8 | 11.2 | 8 | (6, 12) |

| Q4 | 9271 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 8 | (6, 12) |

| Q5 | 9052 | 11.7 | 12.0 | 8 | (6, 12) |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; IMD, index of multiple deprivation; LQ, first quartile; PLOS, postoperative length of stay; UQ, third quartile.

Figure 5.

Estimated odds ratios for each IMD quintile group (relative to IMD Q1) of prolonged postoperative length of stay (points) and 95% CIs (lines). Vertical red line denotes no effect (CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; IMD, index of multiple deprivation).

Discussion

This analysis of national data for patients undergoing cardiac surgery has demonstrated an important influence of social deprivation on outcomes and has described the landscape of social deprivation in England with respect to region. The proportion of patients in the most socially deprived group ranged from over one-third in the North East of England hospitals to less than one-tenth in the East of England. Following adjustment for logistic EuroSCORE, BMI and smoking history, patients undergoing cardiac surgery in the two most deprived quintiles had an increased risk of in-hospital mortality with patients in the three most deprived quintiles at risk of reduced survival. Patients in the three most social deprived groups were at a significant risk of prolonged PLOS.

Survival and postoperative length of stay

Analysis of the overall cohort demonstrated that social deprivation was a significant factor for in-hospital mortality, however, this finding was not consistent between operative groups. Social deprivation quintile had a significant effect on in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing CABG surgery but not in patients undergoing valve+CABG or valve surgery alone. The impact of social deprivation on the risk of in-hospital mortality may be as a result of an increased prevalence of unmeasured comorbidity or poor background health status in the more socially deprived groups. In patients undergoing valve surgery, these factors may be masked by the enhanced effect of measured comorbidity and increasing age.

Survival after all-cardiac surgery was reduced for the most socially deprived groups when compared with the least deprived groups. This relationship was demonstrated for all operative groups with the largest effect size seen in isolated CABG surgery. The fact that social deprivation appears to be a more significant predictor of longer term outcomes is not surprising. First, the analyses use the logistic EuroSCORE which was designed to predict in-hospital mortality for adjustment, meaning that most important risk factors deemed predictive of short-term outcomes are adjusted for. Second, the unmeasured comorbidity, or poor background health status that social deprivation likely represents, would be expected to impact more on midterm survival rather than in-hospital mortality.

Social deprivation also had a significant impact on PLOS with patients in the three most socially deprived groups having an increased risk of prolonged PLOS, and the median PLOS being 1 day longer for patients in IMD Q5. This effect could be explained by poor background health status in socially deprived patients, but is more likely to be as a result of factors requiring the input of social care services such as lack of family support, unavailability of transport or suitable accommodation for safe discharge.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The key strength of this study is that the analysis has been based on a large data set comprising nearly a quarter of a million patients over a 10-year period. Limitations include the fact that IMD score is based on geographical areas containing over 1000 people, meaning IMD scores may not accurately reflect the social deprivation status of individual patients. IMD score is made up of several factors, and the exact reason why social deprivation is associated with adverse outcomes after cardiac surgery is unclear, but it is likely to be due to a range of factors, such as alcohol and substance abuse, poor diet, smoking, diabetes, and poor health education being more prevalent in patients from socially deprived areas. Like all retrospective analyses of observational registry data, missing data are inevitable, however, the NACSA has <2% missing data for most variables used in this study. Multiple imputation methodology could have been utilised, to address missing data, but as a result of previous work,15 16 and because the levels of missing data were low, a more simplistic approach was used.

Cause of death is not recorded in the NACSA database, meaning it is not possible to comment on mode of death and how this may have been influenced by environmental factors, obesity, diabetes, smoking or access to healthcare. Detailed information on smoking status was not available with patients classified simply as never smoked or current/ex-smokers. The association between PLOS and social deprivation was limited to the binary outcome of prolonged PLOS which is a simplistic summary of an important outcome that is a proxy measurement for postoperative complications. The PLOS analysis is also limited because it does not differentiate between patients who died in-hospital or were discharged alive.

Comparison with previous studies

Social deprivation may influence outcomes for many different reasons. Population studies have demonstrated that social deprivation is an independent risk factor for poorer outcome in terms of life expectancy,17 18 control of risk factors contributing to cardiovascular disease,19 and adverse outcomes in other areas of surgery.20–22 In addition, socially deprived populations have a higher incidence of smoking,23 diabetes mellitus,24 and obesity.25 Inequalities in access to healthcare based on socioeconomic status have been identified in other healthcare systems, but it is difficult to find the evidence for this in the UK with specific respect to cardiovascular disease.26 Importantly, in our study, we have found that even when adjusting for smoking, BMI and EuroSCORE, social deprivation is still a significant risk factor.

Policy implications

The implication of the varying demands required to deliver appropriate care levels to differing social groups are that extra resources need to be funded to deliver a similar number of standard operation outcomes. This has national implications for planning and funding healthcare. Implementing public health policies aimed at more socially deprived patients who require cardiac surgery may improve outcomes. There are also important implications when trying to make comparisons between centres in terms of patient outcomes when it has been demonstrated that social deprivation, a risk factor generally not accounted for in risk adjustment models, is an independent predictor of outcomes.

Further research

A further development of this work would be to explore whether the inclusion of social deprivation improves the performance of risk prediction models. In this study, we demonstrated that only small improvements in discrimination are observed by including social deprivation, but model goodness-of-fit has not been assessed. Analysis of other outcomes following cardiac surgery, including cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, and freedom from recurrence of symptoms would also be of interest. Exploring how cause of death following cardiac surgery correlates with IMD quintile would be useful, although this is unlikely to be feasible in the near future, as existing databases do not currently record information on cause of death. The development of tools to examine temporal trends in the social deprivation of patients undergoing cardiac surgery would be useful for assessing the impact of healthcare changes and public health interventions.

Conclusions

The social deprivation of patients undergoing cardiac surgery in England varies by region. Patients from areas of high social deprivation are at an increased risk of adverse outcomes following cardiac surgery, including in-hospital mortality, PLOS and postdischarge survival. This study may have implications for the provision of cardiac surgical services, as centres that deliver care to more socially deprived areas are likely to have a greater burden on their resources. The influence of social deprivation on comparative outcome analyses may also need to be considered.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all members of the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland who contribute data to the SCTS database. The National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research, UCL London, provided the data for this study. The authors would like to thank Mr David Jenkins for reviewing this article on behalf of the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland.

Footnotes

Contributors: JB and BB are consultant cardiac surgeons, and came up with the idea for this study, and were responsible for the design of the study. GLH is a biostatistician who analysed the data with SWG, a cardiothoracic surgery specialist trainee. All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript. JB acts as guarantor and affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained. This manuscript was not commissioned.

Funding: GLH's salary at the time of analysis was funded by Heart Research UK (Heart Research UK Grant RG2583).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This project was approved by the National Adult Cardiac Surgery Research Board—a part of the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research, UCL, London. No patient-identifiable information was available to the authors. All coauthors declare no conflicts of interest in the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The National Adult Cardiac Surgery Audit registry can be obtained from the National Institute of Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR) following approval of a data sharing agreement. Details can be found at: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/nicor/access.

References

- 1.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2468–81. 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison C, Woodward M, Leslie W et al. Effect of socioeconomic group on incidence of, management of, and survival after myocardial infarction and coronary death: analysis of community coronary event register. BMJ 1997;314:541–6. 10.1136/bmj.314.7080.541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkins NM, Jhund PS, McMurray JJ et al. Heart failure and socioeconomic status: accumulating evidence of inequality. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:138–46. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pagano D, Freemantle N, Bridgewater B et al. Social deprivation and prognostic benefits of cardiac surgery: observational study of 44 902 patients from five hospitals over 10 years. BMJ 2009;338:b902 10.1136/bmj.b902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE, Cavelaars AE et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality in western Europe. The EU Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health. Lancet 1997;349:1655–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07226-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roques F, Michel P, Goldstone AR et al. The logistic EuroSCORE. Eur Heart J 2003;24:881–2. 10.1016/S0195-668X(02)00799-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noble M, McLennan D, Wilkinson K et al. The English Indices of Deprivation 2007 http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/communities/pdf/733520.pdf (accessed 14 Jan 2015).

- 8.Shahian DM, O'Brien SM, Filardo G et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 1—coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88(1 Suppl):S2–22. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.05.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrell FE., Jr Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB Sr, D'Agostino RB Jr et al. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 2008;27:157–72. Discussion 207–112 10.1002/sim.2929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994;81:515–26. 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean C, Felder G, Kim AH. Analysis of speech perception outcomes among patients receiving cochlear implants with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder. Otol Neurotol 2013;34:1610–14. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318299a950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, et al. 2013. Ime4: Linear mixed effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version 1.0–5. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Ime4.

- 14.Therneau TM, Grambsch P. Modelling survival data: extending the cox model. New York: Springer, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hickey GL, Grant SW, Cosgriff R et al. Clinical registries: governance, management, analysis and applications. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;44:605–14. 10.1093/ejcts/ezt018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bridgewater B, Hickey GL, Cooper G et al. Publishing cardiac surgery mortality rates: lessons for other specialties. BMJ 2013;346:f1139 10.1136/bmj.f1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eames M, Ben-Shlomo Y, Marmot MG. Social deprivation and premature mortality: regional comparison across England. BMJ 1993;307:1097–102. 10.1136/bmj.307.6912.1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas B, Dorling D, Smith GD. Inequalities in premature mortality in Britain: observational study from 1921 to 2007. BMJ 2010;341:c3639 10.1136/bmj.c3639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashworth M, Medina J, Morgan M. Effect of social deprivation on blood pressure monitoring and control in England: a survey of data from the quality and outcomes framework. BMJ 2008;337:a2030 10.1136/bmj.a2030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clement ND, Jenkins PJ, MacDonald D et al. Socioeconomic status affects the Oxford knee score and short-form 12 score following total knee replacement. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:52–8. 10.1302/0301-620X.95B1.29749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clement ND, Muzammil A, Macdonald D et al. Socioeconomic status affects the early outcome of total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:464–9. 10.1302/0301-620X.93B4.25717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagger JP, Zindrou D, Taylor KM. Postoperative infection with meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and socioeconomic background. Lancet 2004;363:706–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15647-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douglas L, Szatkowski L. Socioeconomic variations in access to smoking cessation interventions in UK primary care: insights using the Mosaic classification in a large dataset of primary care records. BMC Public Health 2013;13:546 10.1186/1471-2458-13-546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bachmann MO, Eachus J, Hopper CD et al. Socio-economic inequalities in diabetes complications, control, attitudes and health service use: a cross-sectional study. Diabet Med 2003;20:921–9. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01050.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scholes S, Bajekal M, Love H et al. Persistent socioeconomic inequalities in cardiovascular risk factors in England over 1994–2008: a time-trend analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. BMC Public Health 2012;12:129 10.1186/1471-2458-12-129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blais C, Hamel D, Rinfret S. Impact of socioeconomic deprivation and area of residence on access to coronary revascularization and mortality after a first acute myocardial infarction in Quebec. Can J Cardiol 2012;28:169–77. 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]