Abstract

Guidelines for children with drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) tend to focus on individual patient care; there is little guidance for national tuberculosis programmes (NTPs) on how to plan, implement and integrate DR-TB services for children. In 2013, through the paediatric tuberculosis (TB) programme started by the Tajikistan Ministry of Health and Médecins Sans Frontières in 2011, 21 children became the first to be treated for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in Tajikistan. We describe the challenges encountered in establishing the programme and the solutions to these challenges, and propose a framework to guide the implementation of paediatric DR-TB care. This framework could prove useful for other NTPs in resource-limited settings.

Keywords: DR-TB, paediatric, Tajikistan

Abstract

Les directives relatives aux enfants atteints de tuberculose pharmacorésistante (TB-DR) ont tendance à se focaliser sur la prise en charge des patients individuels; il y a par contre peu de directives destinées aux programmes nationaux de lutte contre la TB (PNT) sur la manière de planifier, mettre en œuvre et intégrer les services de TB-DR destinés aux enfants. En 2013, dans un programme de prise en charge de la TB pédiatrique démarré par le Ministère de la Santé et Médecins Sans Frontières en 2011, 21 enfants ont été les premiers à être traités pour TB-MDR (TB multi-résistante) au Tadjikistan. Nous décrivons les défis de la mise en œuvre d'un programme et de leurs solutions et proposons un cadre conceptuel d'aide à la mise en œuvre de la prise en charge de la TB-DR pédiatrique. Notre cadre pourrait s'avérer utile pour d'autres PNT dans des contextes de ressources limitées.

Abstract

Las directrices sobre el manejo de los niños con diagnóstico de tuberculosis drogorresistente (TB-MDR) suelen centrarse en la atención del paciente individual; existe poca orientación dirigida a los Programas Nacionales contra la Tuberculosis (PNT) en materia de planeamiento, ejecución e integración de los servicios que se ocupan de la TB-DR en los niños. El Ministerio de Salud y Médecins Sans Frontières iniciaron en el 2011 un programa de TB dirigido a los niños y en el 2013, por primera vez, 21 niños recibieron tratamiento contra la TB-MDR (multidrogorresistente) en Tayikistán. En el presente artículo se describen los obstáculos encontrados durante la introducción del programa, las soluciones que se aportaron y se propone un marco de trabajo encaminado a orientar la ejecución de la atención pediátrica de la TB-MDR. Este marco será útil a otros PNT en entornos con recursos limitados.

The management of children with drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) is challenging. First, there are the difficulties inherent in any form of childhood tuberculosis (TB): non-specific symptoms, paucibacillary disease and difficulties in collecting specimens for microbiological evaluation.1,2 Even when samples are obtained, a positive microbiological diagnosis is made in only a small proportion of children with clinical disease.3 Second, there are the challenges related to DR-TB: the need for microbiological diagnosis, second-line regimens with significant adverse events, few child-friendly formulations, stigma and the politicised nature of the epidemic. In addition, there are programmatic difficulties with little guidance for programme managers. Guidelines for children with DR-TB focus mainly on individual patient care;4,5 little guidance is available for national tuberculosis programmes (NTPs) on planning and implementing DR-TB services for children.

In Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), the number of children developing TB each year is unknown. In 2012, children (age <15 years) constituted 6% of all notified cases in Central Asia (data not available for Turkmenistan).6 There is a relationship between community TB prevalence and the proportion of the total burden found in children; the higher the prevalence, the greater the proportion.7 As the TB prevalence in Central Asia is moderate (75–141 cases per 100 000 population), a higher proportion than is currently reported is predicted and it is therefore likely that many children are not treated. The proportion of new adult TB cases that are multidrug-resistant (MDR, i.e., resistant to at least rifampicin [RMP] and isoniazid [INH]), varies between 13% and 26% within these five countries, and as the proportion of MDR-TB in children is similar to the proportion among new cases in adults,8 it is also likely that a significant number of children with MDR-TB are not being diagnosed and treated.

SETTING

Aspect of interest

Discussions between Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and the Tajikistan Ministry of Health (MoH) identified paediatric TB, and in particular diagnosis and treatment for DR-TB given the high proportion of DR-TB among new cases, as a major gap within the NTP. In response, in 2011, the MoH and the MSF began a paediatric TB programme. The programme focused on implementing best practice and building capacity for the care of children with DR-TB, and its establishment required a significant investment of time and resources. In 2013, 21 children (age <16 years; three aged <5 years), of whom 18 were confirmed and three were presumptive cases, started treatment for MDR-TB. Prior to the programme, no child had ever been treated for MDR-TB in Tajikistan.

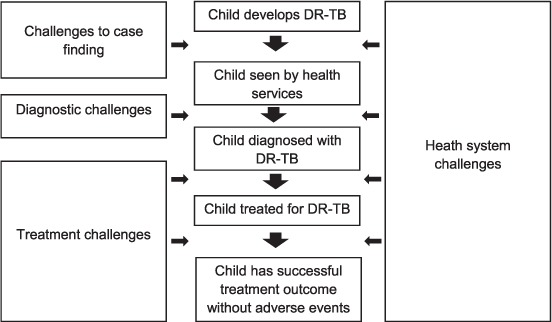

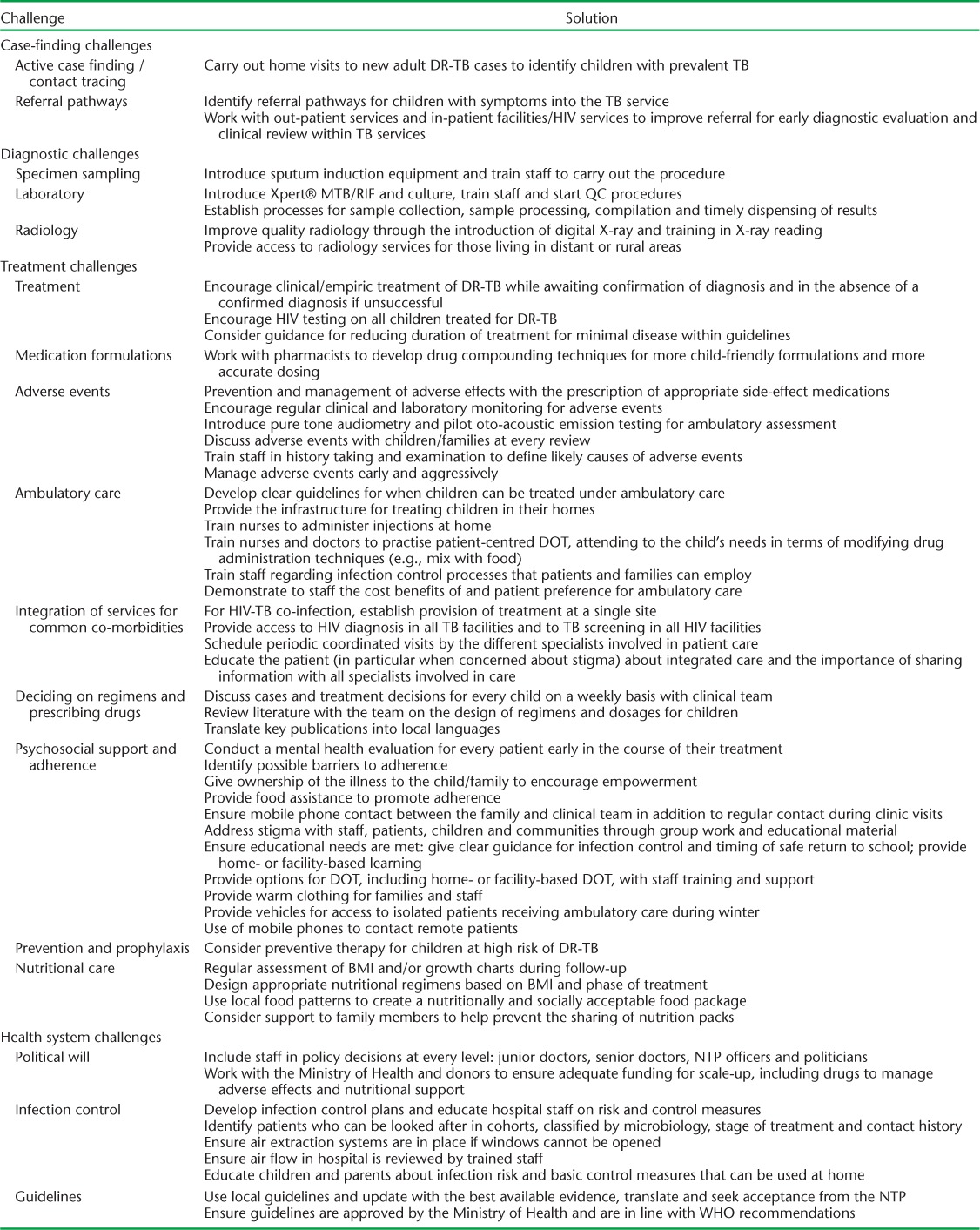

Here we share the lessons learned in this process in the form of a framework intended to help guide other NTPs in resource-limited settings. The framework proposes solutions to the major challenges faced in integrating paediatric DR-TB care into an NTP. The challenges were categorised based on the treatment cascade into case finding, diagnosis, treatment and health systems (Figure). We devised the major themes of the framework based on discussions with the field team and the MSF programme advisers. Revisions drew on author experiences in other DR-TB programmes and from publications related to the programmatic management of paediatric DR-TB;9,10 potential solutions were listed according to priority. The framework is shown in the Table.

FIGURE.

Diagnostic and treatment cascade and health system challenges. DR-TB = drug-resistant tuberculosis.

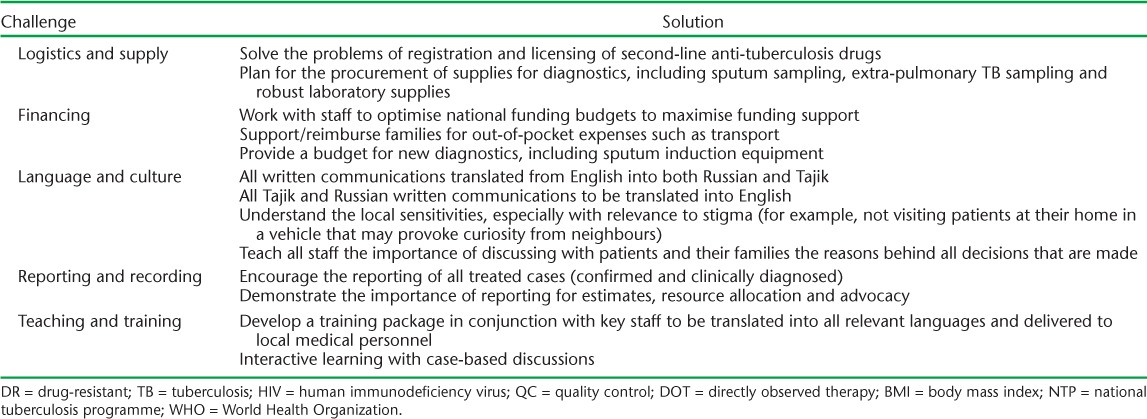

TABLE.

Challenges and solutions to implementing drug-resistant tuberculosis programmes for children

TABLE.

(continued)

Case finding

We initially concentrated on the activities within the paediatric hospital and DR-TB facilities. Next, linkage between adult and paediatric services was strengthened to ensure household contact tracing and appropriate assessment and follow-up of child TB contacts. Screening of households of diagnosed cases for active case finding, INH preventive treatment for contacts of drug-susceptible TB patients, family education about the possible later occurrence of TB in close contacts and the regular follow-up of contacts of DR-TB patients for 2 years were commenced. These activities required consideration of available human resources and the optimal choice of investigations for screening. With limited resources, preventive treatment for DR-TB for young children should be considered, as screening and early detection in this population is extremely difficult in the community. In addition, the importance of mapping all the potential referral pathways of suspected child TB patients was recognised. This ensured that the different health care providers would recognise children at risk for TB and refer them appropriately. Contact tracing had previously been based on X-ray and fluorography, which often hindered evaluation given the cost and difficulty of travelling to radiology facilities for many rural families.

Diagnosis

To improve the diagnosis of TB in children, the collection of specimens was felt to be as important as investment in the laboratory and newer diagnostic tests. Before the project, techniques for specimen collection, such as gastric aspiration and induced sputum, were rarely performed and microbiological culture was not widespread. A phased implementation was undertaken. To develop the technique, the staff first concentrated on introducing sputum induction for children within the main paediatric TB referral hospital. Access was then extended to children living remotely who were brought to the hospital or reimbursed for travel costs. GeneXpert® (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) facilities were introduced, and all samples underwent Xpert® MTB/RIF, culture and drug-susceptibility testing.

Treatment

Prior to the project, common local practice was to treat only confirmed cases of DR-TB with second-line drugs; children presenting with clinical TB disease were usually treated for drug-susceptible TB even following contact with a source case with DR-TB. Treatment was frequently hospital-based for the full duration, with limited psychosocial and nutritional support. Monitoring of adverse events (e.g., regular audiology tests to detect hearing loss) was implemented inconsistently. Interaction between health programmes (TB, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], nutrition, paediatric sub-specialities, etc.) was incomplete, and the coordination of care was challenging. The initial priorities were the development of psychosocial support, logistical assistance for patients in the community, clear management plans for adverse effects and training staff in the appropriate use of empiric DR-TB treatment.

Several challenges were not adequately addressed in the initial guidelines and training: building staff confidence around starting treatment in children based on a history of close DR-TB contact alone, accurate dosing of medications, and providing treatment for young children with minimal disease. As paediatric formulations of second-line drugs are scarce, adult tablets had to be adapted — cut, broken or dissolved — potentially increasing unpalatability, nausea and vomiting. This was addressed through the development of guidance for drug compounding and extemporaneous formulations to improve dosing accuracy and ease of administration. To aid the commencement of the programme, the decision was taken to provide children with the same regimen as adults in terms of duration and medications. This simplified the training and sharing of decision making between adult and paediatric staff. However, it was sometimes a barrier to commencing treatment, due to the reluctance to commit young children with minimal disease (such as lymph node TB) to 20 months of treatment with such a toxic regimen.

Health system

Early and ongoing engagement with the NTP and the provision of specific human and monetary resources were essential. A national guideline was developed in collaboration with NTP staff11 based on best available evidence and international guidance. The identification of a person within each facility responsible for infection control, and the development of a simple infection control plan in discussion with facility staff was essential. The climate in Central Asia complicates infection control, as cold winters mean that simple environmental measures, including window opening, are not possible. In this context of a high burden of DR-TB and limited single rooms, the availability of rapid molecular tests in hospitals and history of close contact with DR-TB cases are important for early cohorting of infectious patients with similar drug resistance patterns. The adaptation of international and national guidelines, with experience from other programmes, was necessary. Language obstacles were overcome through translation and the regular use of interpreters; all guidelines were made available in English, Russian and Tajik. A training programme was developed by identifying key gaps, adapting external materials to the context and incorporating local case studies. Finally, anti-tuberculosis treatment often involves limitations in school attendance or a reduction in social interactions for children. The programme offered recommendations about when it was safe for children to return to school and provided ongoing education in hospital or at home.

DISCUSSION

Our experience shows that many of the challenges involved in the integration of paediatric DR-TB care within TB programmes can be overcome. Effecting change required commitment from political leaders and key stakeholders, as well as substantial funding for resources, training and facilities. This programme benefited from sharing of experience between the MSF and MoH staff. NTPs can commence and scale up paediatric TB activities without the support of international agencies, but require the political will to allocate resources. The scale-up of DR-TB services is often difficult for NTPs, and without specific attention and resources, children can be neglected.

Our systematic framework based on the treatment cascade could prove useful to other NTPs across the Central Asia region and may be generalisable to other resource-limited settings. We recommend that NTPs commencing and scaling up paediatric TB activities use the challenges and potential solutions described here, as well as international guidelines, as a starting point to identify gaps, priorities and available resources. Planning requires interactions with hospitals, out-patient departments, general practitioners and community health staff. In the short and medium term, national and international agencies can help address specific gaps. While the list of challenges is long, NTPs should be encouraged that context-specific solutions can often be found by using a pragmatic approach to identify feasible short-term priorities with available staffing and resources, while identifying longer-term resources and solutions for scale-up and improvement.

Acknowledgments

This article would not have been possible without the support and hard work of many staff members within the Tajikistan Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Population (Dushanbe, Tajikistan) and the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, London, UK) who have worked to improve paediatric TB care in Tajikistan. We thank Sarah Venis of MSF for editing assistance.

There was no funding provided for this work. The programme described is funded by the Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Population, Dushanbe, Tajikistan, and the MSF, London, UK.

Footnotes

DR = drug-resistant; TB = tuberculosis; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; QC = quality control; DOT = directly observed therapy; BMI = body mass index; NTP = national tuberculosis programme; WHO = World Health Organization.

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Hesseling A C, Schaaf H S, Gie R P et al. A critical review of diagnostic approaches used in the diagnosis of childhood tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:1038–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marais B J, Gie R P, Schaaf H S et al. Childhood pulmonary tuberculosis: old wisdom and new challenges. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1078–1090. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1809SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zar H J, Hanslo D, Apolles P et al. Induced sputum versus gastric lavage for microbiological confirmation of pulmonary tuberculosis in infants and young children: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005;365:130–134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17702-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Sentinel Project for Pediatric Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Management of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in children: a field guide. Boston, MA, USA: The Sentinel Project for Pediatric Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis; 2012. http://sentinelproject.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/sentinel_project_field_guide_2012.pdf. Accessed April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Emergency update 2008. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2008. WHO/HTM/TB/2008.402. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241547581_eng.pdf. Accessed April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. WHO/HTM/TB/2013.11. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/index.html Accessed April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donald P R. Childhood tuberculosis: out of control? Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2002;8:178–182. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zignol M, Sismanidis C, Falzon D et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in children: evidence from global surveillance. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:701–707. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00175812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukherjee J S, Joseph J K, Rich M L et al. Clinical and programmatic considerations in the treatment of MDR-TB in children: a series of 16 patients from Lima, Peru. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7:637–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satti H, McLaughlin M M, Omotayo D B et al. Outcomes of comprehensive care for children empirically treated for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in a setting of high HIV prevalence. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e37114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Population. The guidance for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in children of the Republic of Tajikistan. 2nd ed. Dushanbe, Tajikistan: Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Population; 2014. [Google Scholar]