Abstract

Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), unregulated modifications to host macromolecules that occur as a result of metabolic dysregulation, play a role in many diabetes related complications, inflammation and aging, and may lead to increased cardiovascular risk. Small molecules that have the ability to inhibit AGE formation, and even break preformed AGEs have enormous therapeutic potential in the treatment of these disease states. We report the screening of a series of 2-aminoimidazloles for anti-AGE activity, and the identification of a bis-2-aminoimidazole lead compound that possesses superior AGE inhibition and breaking activity compared to the known AGE inhibitor aminoguanidine.

Keywords: Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), Bis-2-aminoimidazole, Aminoguanidine, Diabetes

Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) are unregulated and non-enzymatic modifications to host macromolecules (including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids) that are enhanced in the presence of physiologically elevated levels of sugars, such as glucose.1,2 AGE formation typically occurs as a result of metabolic dysregulation (such as diabetes), but are also an expected component of inflammation and the natural aging process. AGEs are formed when reactive aldehydes, typically derived from reducing sugars, react randomly with proteogenic amines to form an initial Schiff-base that, upon undergoing a subsequent Amadori rearrangement, produces randomly glycated proteins (Fig. 1).1 The diagnostic measurement of glycation, as Amadori modification of the N-terminal valine residue on the β-chain of hemoglobin, known as HbA1c, remains the current gold standard in clinical medicine to evaluate effective glucose control in diabetic patients.3,1 AGE formation has been reported to play a role in a number of diabetes related complications including: retinopathy, cataract, atherosclerosis, neuropathy, nephropathy, diabetic embryopathy, and impaired wound healing.4

Figure 1.

AGE formation on a protein template via Amadori rearrangement.

AGE formation typically drives disease pathology in two major ways. First, the outcome of direct covalent modification can lead to altered proteolytic degradation profiles, disruption of interactions with other molecules, and effects upon the biomechanical characteristics of tissues.5 Second, there are receptor-mediated pathways, such as the binding of AGEs to the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE), which leads to the induction of proinflammatory and procoagulant responses.6 RAGE activation has been implicated in not only the pathogenesis of diabetes, but also Alzheimer’s disease and renal failure.7 The formation of AGEs in both aging and diabetes also leads to augmented cardiovascular risk and more frequent occurrence of vascular disease.8

Given these pleiotropic effects on disease states and contribution to progression of diabetic complications, there have been multiple different avenues explored to combat AGE formation. Of these approaches, the most promising seems to be the use of small molecules that inhibit AGE formation or break pre-existing AGEs (Fig. 2). The gold standard in this field is aminoguanidine (AG), which sequesters reactive aldehyde species as 1,2,4-triazines. AG showed promise in animal studies; however clinical studies for the treatment of complications due to diabetes were canceled due to safety concerns as it was found that AG also inhibited NO synthase.9,10 The other prominent molecule investigated for disrupting AGE formation is ALT-711 (alagebrium).11,12 ALT-711 is a small molecule that was discovered to break pre-formed AGEs and was ultimately pursued by Alteon for commercial development. Despite showing promise in early studies (including advancement to Phase II), development of ALT-711 was halted due to financial complications. This has led to the conclusion that although AG and ALT-711 showed promise, safety and/or efficacy with both compounds have limited their further development.13

Figure 2.

Inhibitors of AGE formation, aminoguanidine (AG) and ALT-711. Structural features shared between AG and the 2-aminoimidazole heterocycle are highlighted in blue.

Based upon these promising initial in vivo studies with AG and ALT-711, we have begun to explore alternative chemical scaffolds that could potentially inhibit AGE formation and/or break existing AGEs. To this end, we have begun to investigate the anti-AGE activity of differentially functionalized 2-aminoimidazoles (2-AIs). The 2-AI contains a guanidine-like functionality embedded within its heterocycle, and thus provides a similar structure to AG itself. Various 2-AIs have been shown to have limited cytotoxicity and toxicity against model organisms,14 and thus may be able to sidestep some of the safety concerns associated with AG and ALT-711. 2-AIs have also been shown to react with aldehydes under ambient conditions,15 thereby providing precedence that in a biological system they may be able to sequester reactive aldehyde species. The main difference between AG and functionalized 2-AIs is their respective pKa’s (12 vs ca. 8.5) and it was unclear how this difference in basicity would impact the overall ability to sequester reactive aldehyde species, although we postulated that simple 2-AI derivatives would most likely be inferior to AG itself due to their attenuated pKa.

We began our studies by selecting seven 2-AI derivatives from our internal chemical library16–21 (as well as one 2-aminobenzimidazole and one carbamate derivative, Fig. 3) and assessed their ability to inhibit AGE formation in comparison to AG itself using a standard fluorescence assay. In this assay, glycolaldehyde (GO) is employed as the glycating reagent while bovine serum albumin (BSA) serves as the protein template for AGE formation to occur. GO (5 mM) and BSA are simply mixed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) in the absence or presence of anti-AGE compounds and the amount of AGE formation is quantified after seven days by fluorescence (370/440nm). The results of this preliminary screen are summarized in Figure 4A.

Figure 3.

Compounds screened for inhibition of AGE formation.

Figure 4.

Compounds with multiple 2-AI heterocycles are most effective at inhibiting AGE formation. Percent inhibition of AGE formation was evaluated with compounds illustrated in Figure 2 by fluorescence (370/440 nm). (A) Initial screening of all compounds. (B) Further evaluation of compounds in A at lower concentration and accounting for autofluorescence; AG, aminoguanidine. *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, compared to AG at the same concentration.

As expected, AG potently inhibited AGE formation and achieved 48.6% inhibition at 4 mM, 19.1% inhibition at 400 μM, and 7.3% inhibition at 40 μM. In comparison (and as predicted), monomeric 2-AI derivatives were inferior to AG; demonstrating inability to significantly inhibit AGE formation at 40 μM and lower. Compound 3 was the most potent recording 63.8% inhibition at 4 mM, 3.2% inhibition at 400 μM, and no inhibition at 40 μM. Surprisingly, compounds that contained multiple 2-AI heterocycles appeared to be potent AGE inhibitors, with all able to outperform AG at 4 mM, and compound 7 outperforming AG at 400 μM, and no significant differences at 40 μM (Fig. 4A).

After this initial evaluation, we recognized that there may be a potential contribution of autofluorescence from the 2-AI derivatives in this assay. Therefore, we further investigated anti-glycating activity of compounds 3, 5, 7, and 8 while correcting for autofluorescence (Fig. 4B). As expected, this second screening demonstrated even better inhibition of glycation over AG by compounds with multiple 2-AI heterocycles at lower concentrations (Fig. 4B). At 400 and 40 μM, compound 7 demonstrated 44.6% and 5.6% inhibition, respectively, while compound 5 inhibited glycation by 62.8% and 15.3%, indicating greater inhibitory activity at lower concentrations compared to AG and suggesting that inhibition of AGE formation is proportional to the number of 2-AI heterocycles. For this study, compounds 5 and 6 were prepared as racemic mixtures, though it would be interesting to follow up by examining the activity of enantiomerically pure derivatives to see if chirality plays a role in the ability of these bis-2AIs to inhibit glycation, and potentially develop more potent analogues.

Of the three structures, we elected to pursue compound 7 for further studies. Compound 7 was chosen based on superior biological activity (which still surpassed AG) and structural simplicity that would allow us to potentially investigate basic mechanistic features of the bis-2-AI scaffold in the context of anti-AGE activity. The first question we chose to pursue was the potential mechanism by which 7 inhibited AGE formation. AG is known to inhibit AGE formation by sequestration of reactive aldehyde species and in the case of methylglyoxal (MG), another reactive aldehyde that leads to AGE formation, produces 3-amino-1,2,4-triazines.22 We reacted AG and MG in PBS and were able to demonstrate that AG was consumed and produced products consistent with 3-amino-1,2,4-triazines (via LCMS). Next, compound 7 was reacted with MG in PBS and the reaction monitored by LCMS. After 24 h, we observed conversion to a new product whose mass was equivalent to compound 7 + 2MG-4. Although we have yet to determine the exact structure of this product, it is clear that compound 7 reacts rapidly with MG and is covalently modified by this reactive aldehyde.

The second point we wanted to address was to provide an alternative method to measure the inhibition of AGE formation outside of the basic fluorescence assay detailed above. Although the BSA/ GO assay is considered a standard in the field, it only provides a crude snapshot of AGE formation as it relies on a fluorescence signal (which represents only a sub-population of the AGE species on glycated proteins) as a proxy for all potential AGEs that could be formed. Therefore, we wanted to take this a step further and quantify the amount of primary amines in the BSA sample as a function of GO treatment in the absence or presence of compound 7 or AG. This was accomplished by again reacting GO with BSA for seven days in the absence or presence of AG or 7 (400 μM) and then isolating the BSA population by dialysis purification with a 7 kDa cutoff. The amount of protein in each sample was then normalized and primary amines were then quantified by reaction with 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBSA)23 (Fig. 5).

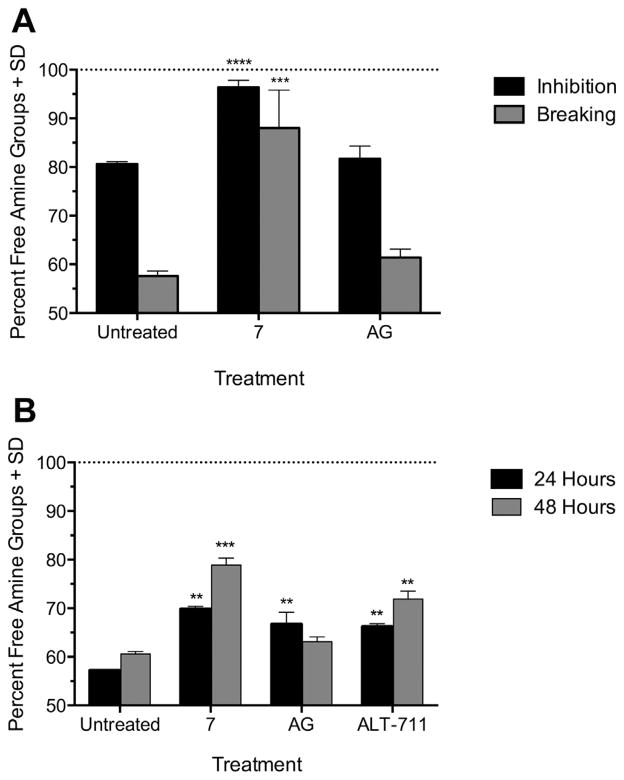

Figure 5.

Compound 7 preserves and restores the frequency of primary amines with an efficacy exceeding AG and ALT-711. (A) Activity of 7 and AG (400 μM) was evaluated by inhibition of GO mediated glycation of BSA or breaking of pre-formed CML-enriched BSA-AGEs, using the TNBSA assay. (B) Breaking activity of 7 by TNBSA assay, compared to AG and ALT-711 (400 μM). Baseline frequency of BSA primary amines is represented by the dotted line at 100%. **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001 compared to untreated.

The GO-BSA reaction in the presence of 7, but not AG, preserved a significant proportion of primary amines in comparison to GO treatment in the absence of either anti-AGE compound. While GO in the absence of anti-AGE compound led to a 19.4% modification and therefore, reduction in primary amines, only a 3.6% reduction was observed in the presence of 7. In contrast, there was still an 18.3% reduction in primary amines in the presence of AG, indicating that 7 is much more effective than AG at inhibiting the overall formation of AGE modifications on primary amines, whether fluorescent or not. These data suggest that while AG is effective at inhibiting AGE formation based on fluorescence, it’s efficacy may be attributed to its ability to disproportionately reduce the formation of fluorescent AGE species in particular, when comparing to measurement of total primary amines by TNBSA. This is especially relevant because the strongest RAGE ligands, such as carboxymethyl lysine (CML) and carboxyethyl lysine (CEL), are non-fluorescent adducts,23 which may be more effectively inhibited by 2-AI derivatives. Moreover, these findings highlight the importance of applying multiple measures of AGE formation to the evaluation of compounds with anti-glycating activity.

Finally, we wanted to investigate whether compound 7 had the ability to break preformed AGEs. From a clinical standpoint, compounds that simply inhibit AGE formation will most likely be useful prophylactically; however compounds that are able to break pre-formed AGEs could potentially reverse the in vivo pathology caused by random glycation and potentially remediate clinical complications due to diabetes and aging. To investigate these effects, we first generated glycated BSA enriched for the formation of CML AGEs24 by incubation with glyoxylic acid (5 mM) under mild reducing conditions with sodium cyanoborohydride (75mM) for 48 h. The CML-BSA was then dialyzed against a 7 kDa cutoff and compound 7 (400 μM) was added then incubated for 24 h. The amount of glycation remaining was then quantified with the TNBSA assay. The breaking activity of 7 after 24 and 48 h was also evaluated against preformed GO AGEs, and compared to the activity of ALT-711 (Fig. 5). Based on untreated reactions in the absence of 7 or AG, it is evident that the CML glycation reaction leads to more frequent modification of primary amines (42.4%) compared to GO. While AG was devoid of breaking ability, 7 increased the number of reactive amines, thereby restoring the amine content of CML-BSA to 88% of the baseline value Fig. 5A. Moreover, 7 also restored the primary amine content of GO-BSA to 78.9% after 48 h, an effect that exceeds the 71.9% restoration afforded by the gold standard ALT-711. Even though AG demonstrated breaking ability at 24 h with CML-AGE it was significantly exceeded by compound 7 after 48 h (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that 7 has exceptional AGE-breaking activity, indicating that 2-AI derivatives may have both prophylactic and therapeutic potential.

In summary, we have shown that compound 7 and other small molecules that contain the 2-AI heterocycle have anti-AGE activity. Compounds that contain multiple tethered 2-AI heterocycles have activity that surpass AG and also have the ability to break preformed AGEs. This promising preliminary result has opened the door to many fundamental questions. These include the exact modifications that 7 is able to inhibit and break, whether this inhibition has functional outcomes both in vitro and in vivo, and whether we can employ structure-based design to deliver analogues of 7 with augmented activity. We are currently pursuing these research avenues and the results of our experiments will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by funding from NIH grants 1R01AI106733-01 (R.J.B., C.M.), R21AI107254-02 (R.J.B.) and 1K01OD016997 (B.K.P.).

References and notes

- 1.Hellwig M, Henle T. Angew Chem. 2014;53:10316–10329. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramasamy R, Vannucci SJ, Yan SS, Herold K, Yan SF, Schmidt AM. Glycobiology. 2005;15:16R–28R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diabetes care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14–S80. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed N. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;67:3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aronson D. J Hypertens. 2003;21:3–12. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, Stern DM. J Clin Investig. 2001;108:949–955. doi: 10.1172/JCI14002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deane R, Singh I, Sagare AP, Bell RD, Ross NT, LaRue B, Love R, Perry S, Paquette N, Deane RJ, Thiyagarajan M, Zarcone T, Fritz G, Friedman AE, Miller BL, Zlokovic BV. J Clin Investig. 2012;122:1377–1392. doi: 10.1172/JCI58642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldin A, Beckman JA, Schmidt AM, Creager MA. Circulation. 2006;114:597–605. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman BI, Wuerth JP, Cartwright K, Bain RP, Dippe S, Hershon K, Mooradian AD, Spinowitz BS. Control Clin Trials. 1999;20:493–510. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(99)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tilton RG, Chang K, Hasan KS, Smith SR, Petrash JM, Misko TP, Moore WM, Currie MG, Corbett JA, McDaniel ML, et al. Diabetes. 1993;42:221–232. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartog JW, Willemsen S, van Veldhuisen DJ, Posma JL, van Wijk LM, Hummel YM, Hillege HL, Voors AA. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:899–908. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willemsen S, Hartog JW, Hummel YM, Posma JL, van Wijk LM, van Veldhuisen DJ, Voors AA. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:294–300. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelen L, Stehouwer CD, Schalkwijk CG. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:677–689. doi: 10.1111/dom.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stowe SD, Tucker AT, Thompson R, Piper A, Richards JJ, Rogers SA, Mathies LD, Melander C, Cavanagh J. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2012;35:310–315. doi: 10.3109/01480545.2011.614620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ying-zi Xu KY, Horne David A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:6981–6984. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballard TE, Richards JJ, Aquino A, Reed CS, Melander C. J Org Chem. 2009;74:1755–1758. doi: 10.1021/jo802260t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards JJ, Reyes S, Stowe SD, Tucker AT, Ballard TE, Mathies LD, Cavanagh J, Melander C. J Med Chem. 2009;52:4582–4585. doi: 10.1021/jm900378s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards JJ, Ballard TE, Melander C. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:1356–1363. doi: 10.1039/b719082d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huigens RW, Reyes S, Reed CS, Bunders C, Rogers SA, Steinhauer AT, Melander C. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers SA, Whitehead DC, Mullikin T, Melander C. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:3857–3859. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu YZ, Yakushijin K, Horne DA. J Org Chem. 1996;61:9569–9571. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solis-Calero C, Ortega-Castro J, Hernandez-Laguna A, Munoz F. J Mol Model. 2014;20:2202. doi: 10.1007/s00894-014-2202-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xue J, Rai V, Singer D, Chabierski S, Xie J, Reverdatto S, Burz DS, Schmidt AM, Hoffmann R, Shekhtman A. Structure. 2011;19:722–732. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kislinger T, Fu C, Huber B, Qu W, Taguchi A, Du Yan S, Hofmann M, Yan SF, Pischetsrieder M, Stern D, Schmidt AM. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31740–31749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]