Abstract

Healing articular cartilage remains a significant clinical challenge because of its limited self-healing capacity. While delivery of autologous chondrocytes to cartilage defects has received growing interest, combining cell-based therapies with scaffolds that capture aspects of native tissue and promote cell-mediated remodeling could improve outcomes. Currently, scaffold-based therapies with encapsulated chondrocytes permit matrix production; however, resorption of the scaffold does not match the rate of production by cells leading to generally low ECM outputs. Here, a PEG norbornene hydrogel was functionalized with thiolated TGF-β1 and crosslinked by an MMP-degradable peptide. Chondrocytes were co-encapsulated with a smaller population of MSCs, with the goal of stimulating matrix production and increasing bulk mechanical properties of the scaffold. Interestingly, the co-encapsulated cells cleaved the MMP-degradable target sequence more readily than either cell population alone. Relative to non-degradable gels, cellularly-degraded materials showed significantly increased GAG and collagen deposition over just 14 days of culture, while maintaining high levels of viability and producing a more diffuse matrix. These results indicate the potential of an enzymatically-degradable, peptide-functionalized PEG hydrogel to locally influence and promote cartilage matrix production over a short period. Scaffolds that permit cell-mediated remodeling may be useful in designing treatment options for cartilage tissue engineering applications.

Keywords: cartilage tissue engineering, chondrocytes, mesenchymal stem cells, tgf-beta (transforming growth factor beta), matrix metalloproteinases

1. Introduction

Articular cartilage has limited self-healing properties, in part due to its lack of innervation and vascularization, and cartilage repair remains a significant clinical challenge. Cartilage is composed primarily of specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) components that absorb water and maintain the structure of the tissue. Chondrocytes are the sole, differentiated resident cells found in mature articular cartilage and are responsible for the generation and maintenance of this ECM.[1]

As a result of its low cellularity and absence of stimulating growth factors provided by vasculature, cartilage exhibits a low rate of regeneration; hence, focal lesions caused by trauma or joint disorders can lead to debilitating osteoarthritis.[2] Matrix-assisted autologous chondrocyte transplantation (MACT) involves encapsulating autologous chondrocytes into a tunable scaffold to promote increased matrix synthesis, which is then implanted into a cartilage defect of a patient.[3] A variety of natural and synthetic materials have been examined as potential cell carriers and as therapeutic agents for cartilage repair.[4],[5],[6],[7]

Despite advances in MACT, a limitation with many of the scaffold carriers is that their resorption rates do not necessarily match the rate of matrix deposition by encapsulated cells (i.e., what is observed in healthy native tissue).[8] In the case of hydrogel carriers, synthetic materials often limit deposition of chondrocyte secreted matrix molecules to the space around the cell, also known as the pericellular space.[9] In order to overcome this issue, current synthetic hydrogels are engineered to hydrolytically degrade at physiologic pH, and while bulk degradation is readily engineered and controlled, numerous material properties are highly coupled to this degradation. For example, high extents of degradation must occur before collagen can assemble throughout hydrogel scaffolds, but this often coincides with a precipitous drop in gel mechanics.[9],[10] Alternatively, hydrogels derived from native matrix components (e.g., collagen, hyaluronan) can be degraded by cells, and this leads to a local degradation mechanism where the rate is dictated by the cells. However, it is often more challenging to control the degradation and mechanical properties of these materials, which can necessitate synthetic modification to these materials to control their time varying properties.[11],[12] As a result, recent efforts in the field have focused on hybrid synthetic ECM-mimics that can capture the tunability of synthetic scaffolds while integrating the properties of a cell-dictated local degradation.

In this work, we explored the application of a peptide and protein functionalized poly-(ethylene glycol) hydrogel for chondrocyte encapsulation and cartilage regeneration. PEG is a hydrophilic polymer that has been broadly explored for cell delivery applications.[13],[14],[15],[16] We formed biologically active PEG hydrogels through a photoinitiated step-growth polymerization scheme, by reacting 4-arm norbornene terminated PEG macromolecules with a non-degradable PEG dithiol linker or a bis-cysteine collagenase-sensitive peptide crosslinker, KCGPQG↓IWGQCK (where the arrow indicates cleavage site).[17] This thiolene photopolymerization allows for precise spatial and temporal control over polymer formation, as well as facile encapsulation of cells and biologics.[18] Multiple studies have shown the resulting crosslinked PEG hydrogel can encapsulate numerous primary cells with high survival rates (>90%) following photoencapsulation.[19],[20]

Previous work in our group further demonstrated that chondrocyte ECM production is enhanced in the presence of locally tethered TGF-β1 in a non-degradable PEG network; however, matrix deposition was limited to the pericellular space.[21] These results motivated the experiments reported herein, where we study how tethered TGF-β1 in concert with a cellullarly degradable peptide crosslinker influences cartilage ECM production and its distribution. Since degradation of collagen is a rate-limiting step in cartilage remodeling, as it is the most abundant component of the ECM,[22] we selected a peptide linker derived from collagen, KCGPQG↓IWGQCK. Previously, the Hubbell group[23] encapsulated chondrocytes in a PEG gel linked with this peptide and found increased gene expression of cartilage matrix molecules compared to non-degradable gels; however, matrix deposition was pericellularly restricted,[24]suggesting that proper degradation did not occur to permit wide-spread ECM deposition. As chondrocytes release both MMP-8 [25] and MMP-13,[26] which are known to cleave this sequence, they are not highly metabolically active.[27] We hypothesize that when these primary cells differentiate from their stem cell origin, their low metabolic activity translates to very slow degradation of MMP-cleavable scaffolds.

To catalyze this pericellular degradation process, we examine the MMP activity of chondrocytes and explore the co-encapsulation of chondrocytes with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to aid in scaffold remodeling. In complementary migration experiments, MSCs have been shown to readily degrade the KCGPQG↓IWGQCK sequence when encapsulated in similar PEG gels.[28] Furthermore, Bahney et al., incorporated a collagen-derived peptide linker into PEG hydrogels to encourage chondrogenesis of MSCs.[29] In addition to catalyzing degradation of the target peptide linker, MSCs co-encapsulated with chondrocytes can also stimulate matrix deposition and reduce hypertrophy of chondrocytes.[30] Furthermore, in clinical settings, a low density of MSCs have the potential to migrate into a PEG MACT scaffold when combined with a procedure like microfracture surgery, which stimulates MSC migration.[31]

In this work, we report the development of a MMP-sensitive PEG based hydrogel that employs co-culture of MSCs and chondrocytes to suggest that local degradation facilitates diffuse ECM deposition. This multifunctional scaffold is further engineered to present TGF-β1 to encourage matrix deposition by both chondrocytes [21] and MSCs.[32] MSCs are seeded at a low density to facilitate degradation of the linker, while allowing us to design experiments focused on ECM secretion by co-encapsulated chondrocytes. Other common co-culture studies utilize much higher ratios of MSCs to chondrocytes.[30],[33] Additionally, we demonstrate in situ degradation by encapsulated cells utilizing a fluorogenic peptide, assess construct matrix deposition both qualitatively and quantitatively, and show increased scaffold mechanical integrity over 14 days.

2. Results

2.1. Chondrocyte cleavage of the MMP-degradable sequence in 3D monoculture

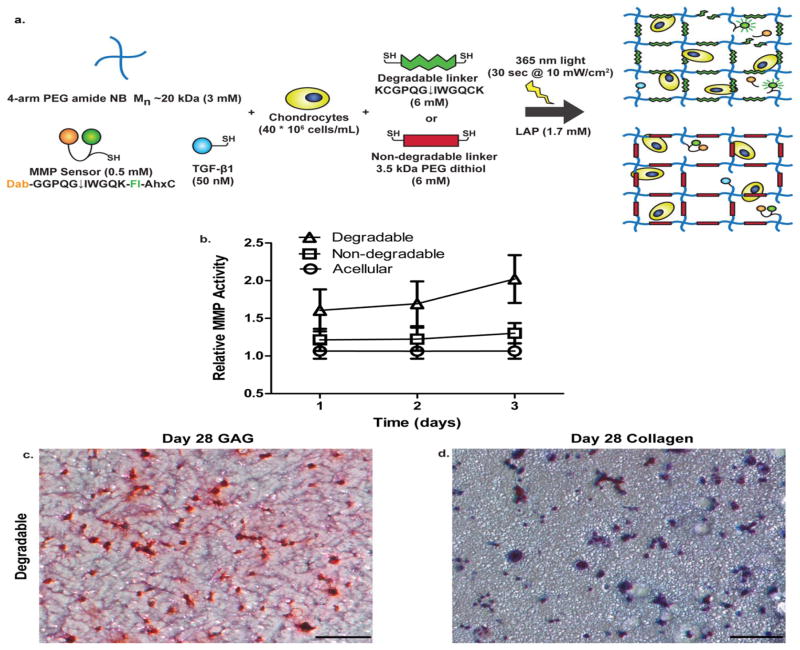

We confirmed in situ degradation of the peptide linker sequence (KCGPQG↓IWGQCK) utilizing a fluorogenic peptide sensor (Dab-GGPQG↓IWGQK-Fl-AhxC) [34] that was covalently tethered to the gel network. Figures 1(a) shows a 4–arm PEG-NB hydrogel formulation, which includes tethered TGF-β1 [50 nM], and fluorogenic peptide sensor [0.5 mM], for experiments used to determine the amount of cleavage of the MMP-sensitive sequence. We chose the chondrocyte seeding density of 40 million cells/mL, because chondrocytes have been studied at this density and shown to produce native-like tissue at this concentration in 3D experiments.[35],[36],[37] Over a 3 day period, we found that chondrocytes seeded at this density degrade the MMP-degradable sequence at a higher rate than either a chondrocyte-laden non-degradable or acellular gel of the same formulation as shown in Figure 1(b). However, when chondrocytes were encapsulated and cultured long term in this formulation, GAG [Figure 1(c)] and collagen [Figure 1(d)] distribution was limited to the pericellular space in degradable, cell-laden constructs, even after 28 days. Even at a shorter culture time of 7 days, the chondrocytes alone do not significantly degrade the surrounding network, which restricts matrix deposition to the pericellular spaces [Figure S2].

Figure 1.

Effect of chondrocytes encapsulated in an MMP-degradable gel. (a) Schematic of 4-arm 20 kDa PEG norbornene network with tethered MMP fluorescent sensor (Dab- GGPQG↓IWGQK-Fl-AhxC), and TGF-β1. The macromer solution, containing tethered peptides, is combined with chondrocytes at 40 million cells/mL. Resultant networks are either crosslinked by an MMP-degradable peptide sequence (KCGPQG↓IWGQCK) or non-degradable (3.5 kDa PEG dithiol) linker for in situ cleavage experiments. (b) Measurement of in situ cleavage of fluorescent sensor by chondrocytes. Over 3 days, acellular and chondrocyte-laden non-degradable gels had similar normalized fluorescent activity, but in a degradable gel, chondrocytes had higher fluorescent activity (where A.U. stands for arbitrary units) suggesting cleavage of the sequence. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n=3). (c) GAG staining of sections obtained at day 28 with chondrocytes seeded in degradable gels at 40 million cells/mL with nuclei stained black and GAGs stained red. (d) Collagen staining of sections obtained at day 28 with chondrocytes seeded in degradable gels at 40 million cell/mL with nuclei stained black and collagen stained blue. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

2.2. Utilization of co-culture to aid in degradation of the MMP-sensitive sequence

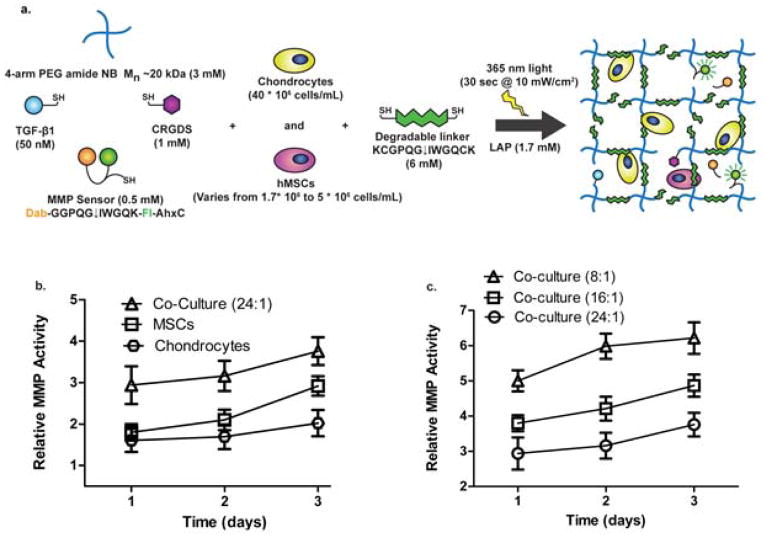

Since chondrocytes alone could not cleave this particular MMP-degradable sequence at a rate that permitted diffuse matrix production, we investigated the use of co-culture with MSCs, as we had previous experience with high levels of degradation of this sequence over shorter time scales.[28],[38] Figure 2(a) shows a 4-arm PEG-NB hydrogel formulation, which includes tethered TGF-β1 [50 nM], RGD [1 mM], and the fluorogenic peptide sensor [0.5 mM] with varying amounts of encapsulated MSCs and a fixed density of chondrocytes, for experiments used to determine cleavage of the MMP-sensitive sequence. Using the same hydrogel formulation over a 3 day period, we found that not only do MSCs seeded at a lower density than chondrocytes degrade the sequence at a faster rate, but there also seems to be a synergistic effect between MSCs and chondrocytes to degrade the sequence at a significantly higher rate. As shown in Figure 2(b), MSCs seeded at 5 million cells/mL cleaved the target sequence faster than chondrocytes seeded at 40 million cells/mL with increasing relative fluorescent activity. Interestingly, when encapsulated in co-culture with a 24:1 chondrocyte: MSC ratio, with chondrocytes held constant at a density of 40 million cells/mL, the cells increased the amount of cleavage of the target sequence compared to either cell type alone. At each time point, the co-culture (8:1) gel [40 million chondrocytes/mL + 5 million MSCs/mL] MMP activity value was significantly higher than a simple additive effect (from the single cell cultures), suggesting there is indeed a synergistic effect of the co-culture on MMP activity.

Figure 2.

Effect of co-culture of chondrocytes and MSCs on degradation of MMP-sensitive sequence. (a) Schematic of 4-arm 20 kDa PEG norbornene network with tethered TGF-β1, RGD, and MMP fluorescent sensor (Dab-GGPQG↓IWGQK-Fl-AhxC) crosslinked by an MMP degradable peptide sequence (KCGPQG↓IWGQCK). Chondrocytes were encapsulated at a fixed seeding density of 40 million cell/mL, and the density of MSCs varied from 1.7 to 5 million cells/mL during the co-encapsulation process for in situ cleavage experiments to measure the effect of co-culture on local degradation. (b) After 3 days, chondrocytes, at 40 million cells/mL, have a lower fluorescent signal than MSCs, at 5 million cells/mL, in degradable gels. Fluorescent signal is highest from day 1 to 3 when cells are co-encapsulated at a ratio of 24:1 chondrocytes: MSCs (40 *10^6 chondrocytes/mL + 1.67*10^6 MSCs/mL). (c) By varying the ratio of chondrocytes to MSCs, and keeping the chondrocyte seeding density constant at 40 million cells/mL, it was found after 3 days, 8:1 yielded the highest amount of degradation out of the tested conditions and was used for subsequent matrix deposition experiments. The MMP activity of each group is significantly different from each other at each timepoint (p<0.05) with the 8:1 condition generating the highest MMP activity. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

In order to determine an appropriate seeding density of MSCs to use in co-culture with chondrocytes in the matrix deposition experiments, we varied the encapsulation ratio of chondrocytes to MSCs. In Figure 2(c), we show that when chondrocytes are held constant at 40 million cells/mL and the concentration of MSCs is increased in the scaffold incrementally, there is a resultant increase in cleavage of the target sequence. There is a statistically significant difference between each of the co-culture groups in Figure 2(c) at each time point (p<0.05) with the 8:1 gel generating the highest MMP activity. Since the lowest ratio of 8:1 chondrocyte: MSC condition yielded the highest fluorescent signal over 3 days, we decided to use this cell ratio for all subsequent experiments.

2.3. Viability of cells and morphology of MSCs in co-culture scaffolds

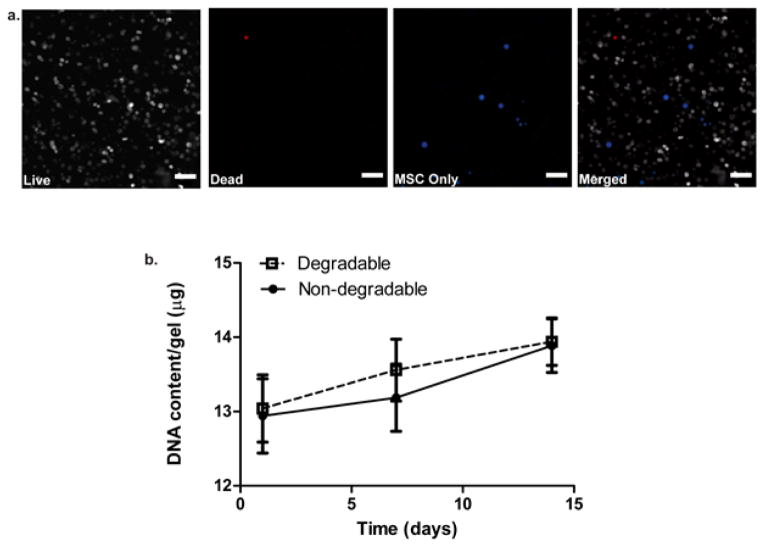

Cell viability for both non-degradable and degradable co-culture gel conditions was assessed by a live/dead membrane integrity assay at both day 1 [Figure 3(a)] and 14 [Figure S3]. Non-degradable gels had a viability of 92 ± 2% at day 1 and 95 ± 4 % at day 14. Degradable gels had a viability of 93 ± 3% at day 1 and 96 ± 2% at day 14 as determined by image quantification where results are presented as mean ± SD (n=3). Since both conditions looked very similar, only the viability results of the degradable condition are shown in this article. In addition to assessing viability, we observed the morphology of MSCs present in the scaffold to see if they maintained a rounded shape to suggest a more chondrogenic phenotype[27] as opposed to an osteogenic phenotype with a more fibroblastic appearance.[38] As shown in Figure 3(a), viability of both chondrocytes and MSCs was high on day 1. Furthermore, MSCs, which have been labeled with Cell Tracker™ Violet prior to encapsulation (blue), retained a spherical morphology in spite of being in a degradable system with integrin-binding epitopes. Moreover, DNA content was assessed at day 1, 7, and 14 [Figure 3(b)]. There was no statistically significant difference in cellularity between degradable and non-degradable conditions, as measured by the amount of DNA present, but there was a steady increase in DNA content from day 1 to 14 in both conditions.

Figure 3.

Viability, morphology and cellularity of co-culture system. (a) Viability at day 1 with degradable 8:1 co-culture gels with live cells (gray), dead cells (red), MSCs labeled with CellTracker™ Violet (blue), and all 3 images merged together. Viability was quantified at 93 ± 3%. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (b) DNA content of degradable and non-degradable 8:1 co-culture gels assessed at day 1, 7, and 14. Both degradable and non-degradable conditions show similar DNA content at each time point, but they increase over the 14 day period. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

2.4. Effect of local degradation on cartilage-specific matrix production and distribution

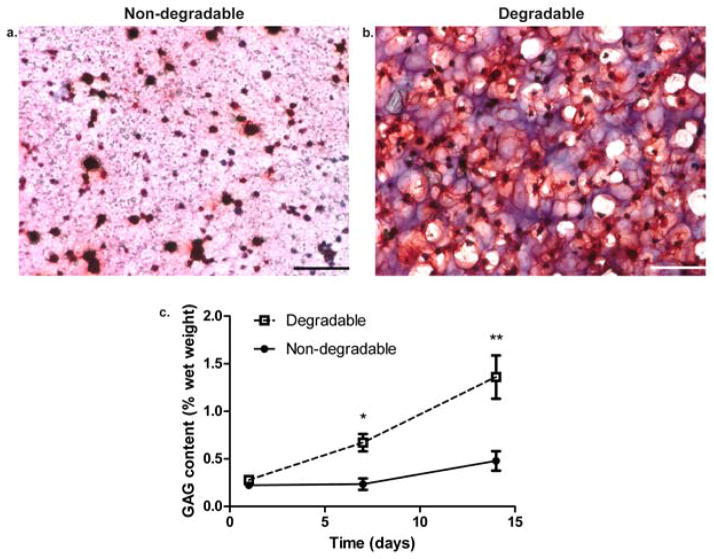

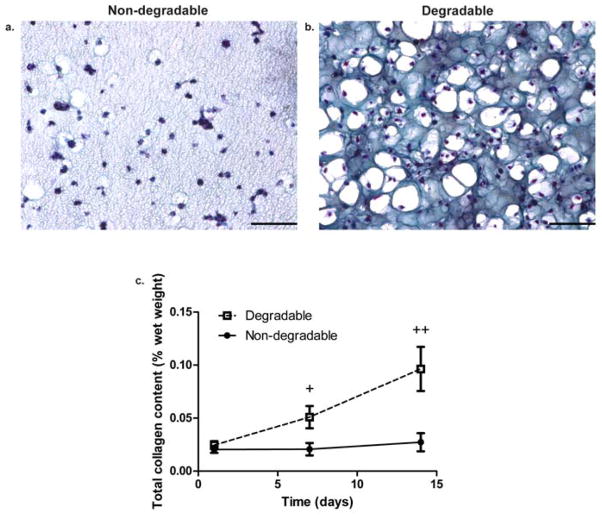

We assessed GAG and total collagen content of gels at day 1, 7, and 14 and further examined the distribution of these molecules throughout the network by staining sections with safranin-O (GAG) and Masson’s trichrome (collagen). Measured quantities of either non-degradable or degradable co-culture scaffolds were normalized to the wet weight [wet weight values shown in Figure S4(a)] of the respective hydrogel formulations. In Figure 4(a) and Figure 5(a), at day 14, GAG and collagen distribution was restricted to the pericelluar space in non-degradable gels. On the other hand, in Figure 4(b) and Figure 5(b), at day 14, GAG and collagen were diffusely distributed throughout the gel and connected with other molecules generated by nearby cells. Not only is the visual difference in distribution striking, but it was further confirmed by quantitative analysis. In Figure 4(c) and Figure 5(c), the sGAG and total collagen production as a percentage of the wet weight of the gel on day 7 and 14 for the degradable construct was significantly higher than the non-degradable gel (p<0.01). While cartilage-specific ECM production increases in both conditions over 14 days, it does so at a significantly higher amount in a locally degradable system.

Figure 4.

Glycosaminoglycan distribution and production in non-degradable and degradable 8:1 co-culture constructs. (a) Non-degradable gel section stained for GAGs at day 14. (b) Degradable gel stained for GAGs at day 14 with nuclei stained black and GAGs stained red. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (c) GAG content expressed as a percentage of the respective construct wet weight assessed at day 1, 7, and 14. * indicates a statistically significant difference in GAG content at day 7 between degradable and non-degradable gels (p<0.01), and ** indicates a statistically significant difference in GAG content at day 14 between degradable and non-degradable gels (p<0.001). Results are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

Figure 5.

Collagen distribution, production, and scaffold compressive modulus in non-degradable and degradable 8:1 co-culture constructs. (a) Non-degradable gel section stained for collagen at day 14. (b) Degradable gel stained for collagen at day 14 with nuclei stained black or violet and collagen stained blue. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (c) Total collagen content expressed as a percentage of the respective construct wet weight assessed at day 1, 7, and 14. + indicates a statistically significant difference in collagen content at day 7 between degradable and non-degradable gels (p<0.05), and ++ indicates a statistically significant difference in collagen content at day 14 between degradable and non-degradable gels (p<0.001). Results are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

2.5. Effect of cell-mediated, local degradation on the mechanical properties of the scaffold

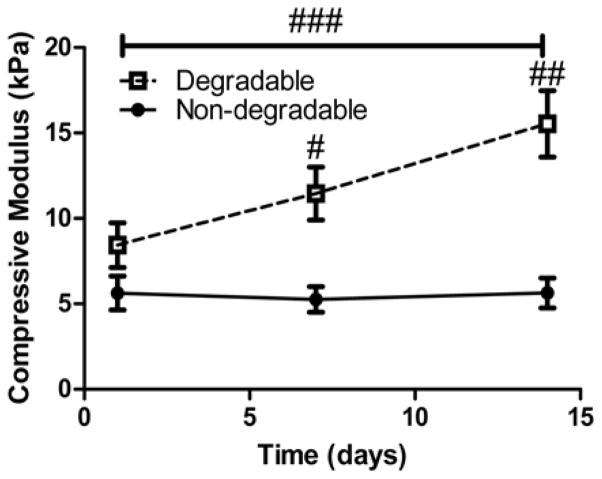

To confirm that our degradable system produced functional, cartilage-specific matrix molecules and increased its mechanical properties over time while permitting ECM expansion, we assessed the bulk compressive modulus of cell-laden non-degradable and degradable gels at day 1, 7, and 14. In Figure 6, at day 7, and 14, the value of the compressive modulus of the degradable construct was significantly higher than of the non-degradable gel (p<0.001). Furthermore, there was a significant increase (p<0.001) between day 1 and 14 of the compressive modulus in degradable scaffolds while the values between day 1 and 14 were not statistically different (p>0.75) with non-degradable gels even though both conditions have similar values of compressive elastic modulus initially.

Figure 6.

Compressive modulus of constructs assessed at day 1, 7, and 14. # indicates a statistically significant difference in modulus value at day 7 between degradable and non-degradable gels (p<0.05) and ## indicates a statistically significant difference in modulus value at day 14 between degradable and non-degradable gels (p<0.001). The line with ### indicates a statistically significant difference between day 1 and day 14 in moduli values for degradable gels only (p<0.001). Results are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

2.6. Quality of composition of ECM in co-culture scaffolds

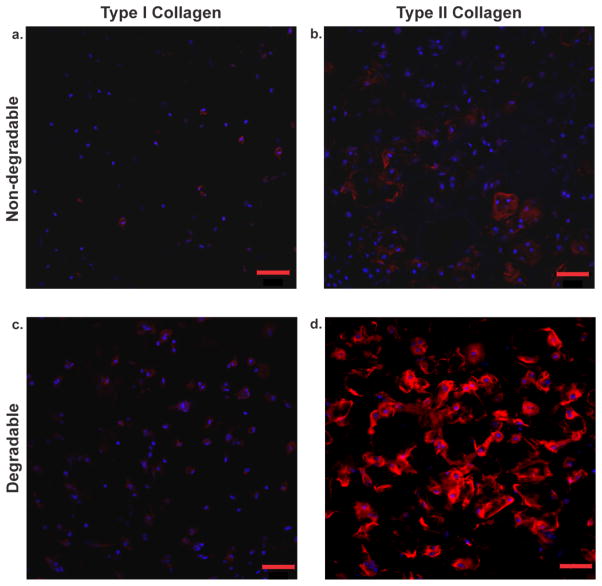

To verify that the ECM produced had an articular cartilage phenotype, we qualitatively assessed the qualitative ratio of type II collagen to type I collagen on gel immunostained sections. Images revealed that at day 14 there was a scarce amount of type I collagen throughout all samples [Figure 7(a,c)]. In contrast, type II collagen was more diffusely distributed in the degradable construct [Figure 7(d)] than in the non-degradable sample, where it was pericellularly restricted and less prevalent [Figure 7(b)]. Quantification of the amount of cells that stained postivie for type I and type II collagen with image analysis revealed similar conclusions. As shown in Table 1, more cells stained positive for type II collagen in the degradable than the non-degradable sample, and the number of cells staining positive for type II collagen was dramatically higher than type I positive cells for both.

Figure 7.

Type I collagen vs. type II collagen distribution assessed by immunofluorescence in non-degradable and degradable 8:1 co-culture constructs. (a) Non-degradable gel section stained for type I collagen at day 14, (b) non-degradable gel section stained for type II collagen at day 14, (c) degradable gel section stained for type I collagen at day 14, (d) degradable gel stained for type II collagen at day 14. Sections were stained for both anti-collagen type I and anti-collagen type II antibodies (red) and were counterstained with DAPI (blue) for cell nuclei. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

Table 1.

Percentage of cells that stained positive for different types of collagen. There is a higher amount of cells that stained positive for type II collagen than type I collagen in both systems. In the degradable system, there is a significantly higher amount of cells that stained positive for type II collagen than there is in the non-degradable system (p<0.01). Results are presented as mean ± SD (n=3).

| Percentage of cells that stain positive for type I or type II collagen in gels at day 14 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-degradable | Degradable | ||

| Type I collagen | Type II collagen | Type I collagen | Type II collagen |

| 26 ± 6 % | 53 ± 7% | 48 ± 6% | 84 ± 4% |

2.7. Effect of inhibition of MMP activity on cartilage-specific matrix production and distribution

We sought to test the effect of inhibiting MMP secretion by encapsulated cells and observe if the resulting matrix production was similar to non-degradable gels. Figure S1(a) shows how the addition of the MMP inhibitor to a co-culture system led to a fluorescent activity level similar to non-degradable gels. Live/Dead staining of gels at day 1 and 14 showed viability greater than 90% (data not shown). Histology staining at day 14 revealed that the co-culture degradable gels treated with the MMP inhibitor had a similar appearance to non-degradable gels with pericellularly limited matrix distribution [Figure S1(b,c)]. These data show how MMP secretion specifically plays a major role in matrix deposition and remodeling within this system, even more so than TGF-β1 or the co-culture synergistic effects.

3. Discussion

Engineering a clinically viable scaffold for promotion of cartilage regeneration is challenging, partly because of the time required to generate a robust matrix by encapsulated cells, especially chondrocytes in monoculture. By utilizing an enzymatically degradable PEG-peptide system with localized presentation of TGF-β1 and co-culture of chondrocytes with MSCs, we have shown quantitatively and qualitatively, in vitro, that encapsulated cells generate highly distributed and elaborate cartilage-specific ECM molecules at a higher rate than in a non-degradable scaffold. This system that responds to cell-mediated cues permits cells to secrete and distribute large matrix molecules that pervade throughout the scaffold and ultimately, should lead to mechanically robust constructs. Furthermore, since the construct utilized the synergistic effects of co-culture (to promote scaffold remodeling) along with the benefits of a tethered growth factor, it expedited ECM generation by encapsulated cells relative to other common cartilage tissue engineering scaffolds.[39],[40]

When chondrocytes were encapsulated in PEG gels linked with an MMP-cleavable peptide at 40 million cells/mL, they produced cartilage tissue that was limited to the pericellular space [Figure 1(b & c)]. This suggests that chondrocytes alone may not sufficiently degrade this particular peptide linker. Chondrocytes have relatively low metabolic activity since they reside in a hypoxic and hyperosmotic environment.[41] This may be part of the reason that the chondrocytes were not observed to secrete MMPs at an appreciable rate in 3D culture.

On the other hand, when encapsulated alone, even at a lower seeding density of 5 million cells/mL, MSCs degraded the sequence at a higher rate than chondrocytes at 40 million cells/mL. This is likely because MSCs are more metabolically active than chondrocytes, as MSCs remodel their environments more frequently during development. There appears to be a synergistic effect between encapsulated MSCs and chondrocytes to degrade the sequence as shown in Figure 2(b) and Figure 2(c). The enhancing effect may be from paracrine signaling between cells to boost each other’s activity.[42] This may be more reflective of the native, developing cartilaginous environment, where MSCs and chondrocytes co-exist before all the MSCs differentiate into chondrocytes.[43] Furthermore, MSCs may play a role in cell number in the system, as they are known to drive chondrocyte proliferation in co-culture.[30] Future experiments could delve deeper into the signaling effects as to why there is increased MMP activity in co-culture between MSCs and chondrocytes. Additionally, studies could look for alternate ways to permit cell-mediated local degradation, which include investigating other peptide linker sequences that are more amenable to cleavage by chondrocyte-secreted enzymes.

In these experiments, a 4-arm 20 kDa PEG backbone at 6 wt% was used for co-culture experiments, since this formulation was studied in the aforementioned MSC experiments to assist in degradation of the peptide linker.[28],[38] Other studies investigating the gel crosslink density on matrix production by encapsulated cells found that scaffolds with a lower crosslinking density, like our monomer formulation, best supported ECM deposition in hydrogels.[10],[44]

Extracellular matrix production data revealed that over just 14 days, the cell-mediated degradable gels permitted greater and widely distributed matrix production than non-degradable gels as revealed in Figures 4, 5, & 6. Furthermore, compressive modulus measurements confirmed that degradable constructs had superior mechanical properties relative to non-degradable gels as shown in Figure 6. There is a steadily increasing trend in modulus values over a short period of time which suggests that the matrix macromolecules generated in the degradable construct assemble in an appropriate fashion to stiffen the mechanical properties of the scaffold.[45] It is interesting to note that there are pockets of space around the cells in the degradable gel histology images, while only a few are present in non-degradable histology images. These pockets have a similar appearance to lacunae found in cartilage and could be due to pericellular degradation of the network. It is evident that cartilage ECM molecule distribution is wide-spread throughout the degradable scaffold, which likely led to the superior functional mechanical properties of the gel while the pericellularly restricted matrix in the non-degradable gels did not lead to an increased modulus.

The rate at which cartilage matrix molecules are produced and assembled in the locally-degradable constructs is substantial. Compared to the bulk degradation mechanism of hydrolytically cleavable PEG-PLA gels that use chondrocytes at 75 million cells/mL,[11] our system produces greater than 2.5 fold increase in GAGs (% wet weight) after 2 weeks while also increasing modulus over time. Furthermore, when compared to a PEG/Chondroitin sulfate copolymer gel with encapsulated chondrocytes at 75 million cells/mL,[40] our system produces greater than 6 fold increase in total collagen content (% wet weight) over 2 weeks. Since matrix production is relatively rapid in these constructs, long culture times may not be necessary like they are in conventional cartilage tissue engineering experiments.

There was a concern that encapsulated MSCs in the co-culture system could lead to fibrocartilage formation as they do in monoculture in scaffolds.[46] However, past studies of co-culture scaffolds with higher amounts of MSCs have confirmed that the neotissue generated is not of fibrocartilagenous nature.[33] Furthermore, after a day, MSCs maintain a spherical morphology in co-culutre, which could indicate a chondrogenic phenotype as shown in Figure 3(a). Additionally, collagen typing (high type II: type I collagen ratio by immunofluorescence) revealed an articular cartilage phenotype with type II collagen being diffusely distributed in degradable gels [Figure 7]. Future studies could track the long-term fate of the MSCs in this co-culture system to ensure they maintain a chondrogenic phenotype and do not revert to generating fibrocartilage or bone.

In a potential clinical application as a MACT scaffold, this system could be advantageous due to the low amount of MSCs needed for co-culture. The subchondral bone under the cartilage defect could be stimulated by a technique like microfracture to recruit MSCs into the environment. The chondrocyte-laden PEG construct could then be implanted into the defect and the MSCs could migrate into the gel. Because only a small quantity of MSCs is required to initiate degradation of the target sequence, there is clinical potential with this technique. Furthermore, it is known that increased age of encapsulated chondrocytes can lead to increased MMP activity of the cells.[8] Future studies should focus on optimizing the chondrocyte: MSC seeding ratio and the monomer formulation to further tune the local degradation and enhance ECM production. Additional studies could confirm whether older chondrocytes might degrade this system without the aid of MSCs, and one could test the influence of various localized growth factors (e.g., TGF-β, Insulin-like growth factor) on promoting the secretory properties and ECM deposition by aged cells. It would also be interesting to see how matrix production is affected as the length of culture time is extended, especially in an in vivo environment.

4. Conclusion

A cell-mediated degradable hydrogel system based on peptide and protein functionalized PEG hydrogels was designed to allow local cell degradation in a manner that promotes diffuse cartilage ECM production, which ultimately leads to constructs with improved mechanical properties over just 14 days. The approach exploited the synergistic effects of co-culture between MSCs and chondrocytes to facilitate degradation of a collagen-derived, MMP-degradable peptide sequence (KCGPQG↓IWGQCK) as well as to promote cartilage ECM production in the presence of tethered TGF-β1. Results confirmed that both encapsulated cell types maintained a high viability and a spherical morphology in the gels. Furthermore, the generated ECM resembles articular cartilage with respect to collagen typing by immunofluorescent staining (high type II collagen: type I collagen ratio). Local degradation seems to play a critical role in matrix elaboration with tissue engineering constructs, and non-degradable constructs of the same formulation had significantly less ECM production and lower moduli values over 14 days. This PEG hydrogel system may prove useful in applications as a scaffold for in vivo cartilage regeneration.

5. Experimental Section

PEG monomer synthesis

4-arm poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) amine (Mn~20,000) was modified with norbornene end groups as previously described.[15] Briefly, 5-norbornene-2-carboxylic acid (predominantly endo isomer, Sigma Aldrich) was first converted to a dinorbornene anhydride using N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (0.5 molar eq. to norbornene, Sigma Aldrich) in dichloromethane. 4-arm PEG amine (JenKem Technology) was then reacted overnight with the norbornene anhydride (5 molar eq. to PEG amines) in dichloromethane. Pyridine (5 molar eq. to PEG amines) and 4-dimethylamino pyridine (0.05 molar eq. to PEG amines) were also included. The reaction was conducted at room temperature under argon. End group functionalization was verified by 1H NMR (Varian 400 MHz) to be >90%. The photoinitiator lithium phenyl-2,4,6- trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) was synthesized as described.[20] Peptides were purchased from American Peptide Company, Inc., which included a MMP-degradable crosslinker (KCGPQG↓IWGQCK) and a pendant adhesion peptide sequence derived from fibronectin (CRGDS). The non-degradable 3.5 kDa PEG dithiol linker was purchased from JenKem Technology.

Cell harvest and expansion

Primary chondrocytes were isolated from articular cartilage of the femoral-patellar groove of 6-month-old Yorkshire swine as detailed previously.[47] Cells were grown in a T-75 culture flask with media as previously described.[48] Briefly, chondrocytes were grown in growth medium (high glucose DMEM supplemented with ITS+ Premix 1% v/v (BD Biosciences), 50 mg/mL L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, 40 μg/mL L-proline, 0.1 μM dexamethasone, 110 μg/mL pyruvate, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-fungizone) with the addition of 10 ng/mL IGF-1 (Peprotech) to maintain cells in a de-differentiated state. ITS was used because it promotes formation of articular cartilage over serum.[49] Cultures were maintained at 5% CO2 and 37 °C.

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were isolated from bone marrow aspirates (Lonza) as previously described.[28] Cells were grown in low glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin-fungizone, and 1 ng/mL recombinant human fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2, Peprotech). MSCs that were passaged two times were used for encapsulation experiments.

Hydrogel formulation and cell encapsulation

Human TGF-β1 (Peprotech) was thiolated using 2-iminothiolane (Pierce) as previously described.[32] Briefly 2-iminothiolane was reacted at a 4:1 molar ratio of TGF-β1 for 1h at RT. Thiolated TGF-β1 was pre-reacted with a PEG norbornene monomer solution prior to cross-linking in the hydrogel formulations at a predetermined concentration of 50 nM. This concentration was selected based on previous work, demonstrating a maximal response from chondrocytes seeded at 40 million cells/mL.[21] Additionally, 1 mM CRGDS was added to promote survival of the encapsulated MSCs.[50] RGD was not added to the chondrocyte-only system as it has previously been shown to have no impact on chondrocyte metabolic activity. [51] Both growth factors were coupled to PEG norbornene via photoinitiated thiolene polymerization with 1.7 mM LAP and light (I0 ~3.5 mW/cm2 at λ=365 nm, ThorLabs M365L2-C2) for 30 seconds. Subsequently, the monomer solution was crosslinked using a degradable MMP linker (KCGPQG↓IWGQCK, MW~1800 kDa) or 3.5 kDa PEG dithiol at a 1:1 [thiol: ene] stoichiometric ratio of [12 mM thiol in either bis-cysteine peptide, or dithiol]: [12 mM norbornene] in a 6 wt% PEG solution using additional light (I0 ~3.5 mW/cm2 at λ=365 nm, ThorLabs M365L2-C2) for 30 seconds. For all experiments, 40 μL cylindrical gels (O.D. ~ 5 mm, height~ 2 mm) were formed in the cut end of a 1 mL syringe. Since the degradable MMP linker is synthesized in an acidic solution, the pH of the final solution was adjusted to 7, so as to not interfere with the bioactivity of the tethered TGF-β or the viability of encapsulated cells. Unless otherwise specified, chondrocytes were co-encapsulated at 40 million cells/mL along with MSCs at 5 million cells/mL at an 8:1 chondrocyte: MSC ratio in 6 wt% monomer solution with tethered TGF-β and RGD. After gel formation, the cell-laden constructs were immediately placed in 48-well non-treated tissue culture plates with 1 mL DMEM growth medium (without phenol red). Media was changed every 3 days. For viability and morphology studies, MSCs were labeled with CellTracker™ Violet BMQC dye (Life Technologies) prior to encapsulation. At day 1 and 14, cell viability was assessed using a LIVE/DEAD® (Life Technologies) membrane integrity assay and confocal microscopy. Cell viability was quantified by image analysis using ImageJ software.

In situ confirmation of MMP cleavage in a 3D microenvironment

To determine whether the specific variant of the collagen-derived MMP degradable linker sequence used in the experiments (KCGPQG↓IWGQCK) was being cleaved by encapsulated cells, a fluorescently labeled peptide sensor of the same sequence was tethered in the gel. Leight et al., developed the fluorogenic peptide substrate Dab-GGPQG↓IWGQK-Fl-AhxC using solid phase peptide synthesis (Tribute Peptide Synthesizer, Protein Technologies, Inc.) as previously described.[34] When the MMP-sensitive sequence is cleaved, it separates the quencher dabycl (Dab) from the fluorophore, fluorescin (Fl), permitting excitation. This fluorescent peptide was tethered into the gel at 0.5 mM along with TGF-β1 [50 nm] and RGD [1mM] prior to crosslinking as depicted in Figure 2(a). Various ratios of co-culture seeding densities were used to determine which formulation degraded the sequence at an appreciable rate. As a control, the fluorescence of an acellular gel was measured over 4 days. For chondrocytes in monoculture, cells were encapsulated at 40 million cells/mL, and for MSCs in monoculture, cells were seeded at 5 million cells/mL. For co-culture experiments, cells were seeded at 8:1, 16:1, and 24:1 (chondrocyte: MSC) where the chondrocyte cell seeding density was held constant at 40 million cells/mL. For MMP inhibitor experiments, the inhibitor GM 6001 (Millipore) was added at a concentration of 100 μM to the media with co-culture gels every 3 days, and viability was tested at day 1 and 14. All values were normalized to the fluorescence value obtained immediately after gel formation (labeled day 0). Fluorescence measurements were conducted using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek) at 494 nm excitation/521 nm emission. An area scan was performed using a 48 well plate format with a 7X7 matrix, and the average fluorescent intensity was calculated for the entire matrix.

Wet weight, compressive modulus, and biochemical analysis

On days 1, 7, and 14, hydrogels were removed from culture (n=3), weighed directly on a Mettler Toledo scale to determine the wet weight, and assessed for compressive modulus. Cell-laden constructs were subjected to unconfined compression to 15% strain at a strain rate of 0.5 mm/min to obtain stress-strain curves (MTS Synergie 100, 10N using TestWorks® 4 software). The modulus was estimated as the slope of the linear region of the stress-strain curves. Immediately afterwards, gels were snap frozen in LN2 and stored at −70°C till biochemical analysis. Hydrogels were digested in 500 μL enzyme buffer (125 μg/mL papain [Worthington Biochemical] and 10 mM cysteine) and homogenized using 5 mm steel beads in a TissueLyser (Qiagen) that vibrates at 30 Hz for 10 min. Homogenized samples were digested overnight at 60°C.

Digested constructs were analyzed for biochemical content. DNA content was measured using a Picogreen assay (Life Technologies). Sulfated glycosaminoglycan (sGAG) content was assessed using a dimethylmethylene blue assay as previously described with results presented in equivalents of chondroitin sulfate.[52] Collagen content in the gels was measured using a hydroxyproline assay where hydroxyproline is assumed to make up 10% of collagen.[53] Additionally, digested acellular gels of either non-degradable or degradable formulations with tethered TGF-β1 and RGD were assessed by the colorimetric assays using the Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek), and the resulting values were subtracted from their respective cell-laden sample values. GAG and collagen content were expressed as a percentage of the wet weight of the respective gels.

Histology and immunofluorescent analysis

On day 14, constructs (n=3) were fixed in 10% formalin for 30 min at RT, then snap frozen and cryosectioned as previously described.[54] Sections were stained for safranin-O and Masson’s trichrome on a Leica autostainer XL and imaged in brightfield (20X objective) on a Nikon (TE-2000) inverted microscope.

For immunostaining, on day 14, sections were blocked with 5% BSA, then analyzed by anti-collagen type II (1:50, US Biologicals) and anti-collagen type I (1:50, Abcam). Sections were pre-treated with appropriate enzymes for 1 h at 37°C: hyaluronidase (2080 U) for collagen II, and pepsin A (4000 U) with Retrievagen A (BD Biosciences) treatment for collagen I to help expose the antigen. Sections were probed with AlexaFluor 555-conjugated secondary antibodies and counterstained with DAPI to reveal cell nuclei. All samples were processed at the same time to minimize sample-to-sample variation. Images were collected on a Zeiss LSM710 scanning confocal microscope with a 20X objective using the same settings and post-processing for all images. The background gain was set to negative controls on blank sections that received the same treatment. Positive controls were performed on porcine hyaline cartilage for collagen type II and porcine meniscus for collagen type I [Figure S5]. The amount of cells that stained positive for each type of collagen was quantified by image analysis using Image J software.

Statistical Analysis

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferonni post-test for pairwise comparisons was used to evaluate the statistical significance of the data where the factors were culture time and hydrogel condition. One-way ANOVA was used to assess differences between conditions at specific time points for cases with two and three different groups. p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Kyle Kyburz and Chun Yang for providing MSCs, as well as Amanda Meppelink and Richard Erali for providing knees on which chondrocyte isolations were performed. The authors would also like to acknowledge Emi Tokuda for helping purify the fluorescent peptide sensor as well as Dr. William Wan, Dr. Huan Wang for assistance on experimental design, and Russell Chagolla for help with image analysis. Funding for these studies was provided by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Department of Defense award number W81XWH-10-1-0791. The US Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, 820 Chandler Street, Fort Detrick MD 21702-5014 is the awarding and administering acquisition office.

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Balaji V. Sridhar, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, and the Biofrontiers Institute, University of Colorado, 596 UCB, Boulder, Colorado, 80303-0596, USA

J. Logan Brock, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, and the Biofrontiers Institute, University of Colorado, 596 UCB, Boulder, Colorado, 80303-0596, USA.

Jason S. Silver, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, and the Biofrontiers Institute, University of Colorado, 596 UCB, Boulder, Colorado, 80303-0596, USA

Prof. Jennifer L. Leight, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, and the Biofrontiers Institute, University of Colorado, 596 UCB, Boulder, Colorado, 80303-0596, USA. Department of Biomedical Engineering and Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, 291 Bevis Hall, Columbus, Ohio, 43210 USA. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Colorado, 596 UCB, Boulder, Colorado, 80303-1904, USA

Mark A. Randolph, Email: randolph.mark@mgh.harvard.edu, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Laboratory for Musculoskeletal Tissue Engineering, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 55 Fruit St., WAC 435, Boston, Massachusetts, 02114, USA. Division of Plastic Surgery, Plastic Surgery Research Laboratory, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 15 Parkman St., WACC 453, Boston, Massachusetts, 02114, USA

Prof. Kristi S. Anseth, Email: kristi.anseth@colorado.edu, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, and the Biofrontiers Institute, University of Colorado, 596 UCB, Boulder, Colorado, 80303-0596, USA. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Colorado, 596 UCB, Boulder, Colorado, 80303-1904, USA

References

- 1.Adolphe M. Biological regulation of the chondrocytes. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falah M, Nierenberg G, Soudry M, Hayden M, Volpin G. Int Orthop. 2010;34:621. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-0959-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kon E, Verdonk P, Condello V, Delcogliano M, Dhollander A, Filardo G, Pignotti E, Marcacci M. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:1565. doi: 10.1177/0363546509351649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim IL, Mauck RL, Burdick JA. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8771. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutson CB, Nichol JW, Aubin H, Bae H, Yamanlar S, Al-Haque S, Koshy ST, Khademhosseini A. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:1713. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kock L, van Donkelaar CC, Ito K. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:613. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1243-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiller KL, Maher SA, Lowman AM. Tissue Eng Part B. 2011;17:281. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forsyth CB, Cole A, Murphy G, Bienias JL, Im HJ, Loeser RF. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1118. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.9.1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicodemus GD, Skaalure SC, Bryant SJ. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:492. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryant SJ, Anseth KS. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59:63. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant SJ, Anseth KS. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;64:70. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao W, Jin X, Cong Y, Liu Y, Fu J. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2013;88:327. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hume PS, He J, Haskins K, Anseth KS. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3615. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deforest CA, Anseth KS. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;124:1852. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aimetti AA, Machen AJ, Anseth KS. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6048. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benton JA, Fairbanks BD, Anseth KS. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6593. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Halevi AE, Nuttelman CR, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. Adv Mater. 2009;21:5005. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoyle CE, Bowman CN. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:1540. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz MP, Fairbanks BD, Rogers RE, Rangarajan R, Zaman MH, Anseth KS. Integr Biol (Camb) 2010;2:32. doi: 10.1039/b912438a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6702. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sridhar BV, Doyle NR, Randolph MA, Anseth KS. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102:4464. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manicourt DH, Devogelaer JP, Thonar EJ. In: Dynamics of Bone and Cartilage Metabolism. Seibel M, Robins SP, Bilezikian JP, editors. Elsevier Science; Burlington: 2006. pp. 421–439. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:47. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park Y, Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA, Hunziker EB, Wong M. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:515. doi: 10.1089/107632704323061870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chubinskaya S. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.11023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu P, DeLassus E, Patra D, Liao W, Sandell LJ. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:1199. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Z, Willers C, Xu J, Zheng MH. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1971. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyburz KA, Anseth KS. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:6381. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bahney CS, Hsu CW, Yoo JU, West JL, Johnstone B. FASEB J. 2011;25:1486. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-165514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bian L, Zhai DY, Mauck RL, Burdick JA. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:1137. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steadman JR, Briggs KK, Rodrigo JJ, Kocher MS, Gill TJ, Rodkey WG. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:477. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCall JD, Luoma JE, Anseth KS. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2012;2:305. doi: 10.1007/s13346-012-0090-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dahlin RL, Kinard LA, Lam J, Needham CJ, Lu S, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Biomaterials. 2014;35:7460. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leight JL, Alge DL, Maier AJ, Anseth KS. Biomaterials. 2013;34:7344. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverman RP, Passaretti D, Huang W, Randolph MA, Yaremchuk MJ. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:1809. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199906000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Passaretti D, Silverman MJ, Huang RP, Kirchhoff W, Ashiku CH, Randolph S, Yaremchuk MA. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:805. doi: 10.1089/107632701753337744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ibusuki S, Papadopoulos A, Ranka M, Halbesma G, Randolph M, Redmond R, Kochevar I, Gill T. J Knee Surg. 2010;22:72. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson SB, Lin CC, Kuntzler DV, Anseth KS. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3564. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bryant SJ, Bender RJ, Durand KL, Anseth KS. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;86:747. doi: 10.1002/bit.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bryant SJ, Arthur JA, Anseth KS. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:243. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coimbra IB, Jimenez SA, Hawkins DF, Piera-Velazquez S, Stokes DG. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:336. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu L, Prins HJ, Helder MN, van Blitterswijk CA, Karperien M. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:1542. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall BK. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987:255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bryant SJ, Chowdhury TT, Lee DA, Bader DL, Anseth KS. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:407. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000017535.00602.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hardingham T, Fosang A. FASEB J. 1992;6:861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huey D, Hu J, Athanasiou K. Science (80-) 2012;6933:917. doi: 10.1126/science.1222454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoo JJ, Bichara DA, Zhao X, Randolph MA, Gill TJ. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;99:102. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byers BA, Mauck RL, Chiang IE, Tuan RS. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1821. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chua KH, Aminuddin BS, Fuzina NH, Ruszymah BHI. Eur Cell Mater. 2005;9:58. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v009a08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salinas CN, Anseth KS. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2370. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villanueva I, Weigel CA, Bryant SJ. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:2832. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farndale RW, Sayers CA, Barrett AJ. Connect Tissue Res. 1982;9:247. doi: 10.3109/03008208209160269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woessner JF. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1961;93:440. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(61)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruan JL, Tulloch NL, Muskheli V, Genova EE, Mariner PD, Anseth KS, Murry CE. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2013;19:794. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.