Abstract

We report on the wavelength dependence of second harmonic generation (SHG) of collagen in scattering tissues over the wavelength range of 800–1200 nm. The study incorporates inclusion of the molecular hyperpolarizability β of collagen and optical scattering, both of which are wavelength dependent. Using 3D SHG imaging and Monte Carlo simulations, we find the wavelength dependence of β is not well described by a two-state model based on known absorption bands. We further find that longer wavelength excitation is inefficient as the reduction in scattering is overcome by the decreased β far from resonance and the optimal excitation is within the 800–900 nm range. The impact is larger for backward collected SHG.

Second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging microscopy has emerged as a powerful modality for visualizing the collagen assembly in a wide range of normal and diseased tissue types. Applications for imaging structural changes in many pathologic conditions [1], including cancers [2,3] fibroses [4], and connective tissue disorders [5] have received considerable attention, as changes in the collagen rich extracellular matrix (ECM) are often revealed by SHG imaging via changes in morphology, intensity, and polarization properties.

Despite the increasing use of SHG imaging, the underlying physics of the contrast have not yet been fully and rigorously explored. Of particular interest is the wavelength dependence of the conversion efficiency, which is related to the magnitude of the first order molecular hyper-polarizability tensor, β, in collagen. The measured quantity in an imaging experiment is a compounded effect of second order nonlinear susceptibility tensor χ(2), which is related to the orientational average of β as well as the phase matching. The latter is proportional to a sinc2 function of Δk, which is related to the refractive index mismatch between the laser and SHG wavelengths [6,7]. Additionally, in tissues of one or more scattering lengths of thickness (i.e., 20–50 μm) the measured intensity is a coupled response of the conversion efficiency with optical scattering [5]. From one perspective, longer wavelengths should be superior for SHG imaging, due to decreased scattering at both the laser and SHG wavelengths, allowing deeper penetration and collection, respectively. However, while SHG does not arise from absorbance, the intensity can be resonance enhanced when the excitation wavelength overlaps with either a one- or two-photon absorption band. The wavelength dependence can be related by the two-state model [8]:

| (1) |

where ω0 is the resonance frequency of an absorption band, and ω1 and ω2 are the excitation and emission angular frequencies, respectively; f and Δμ denote the oscillator strength and change in dipole moments between ground and excited states, respectively, and are assumed to be wavelength independent. For collagen, the nearest potentially relevant absorption band has a one-photon absorption maximum of ~360 nm, arising from crosslinks [9].

Several previous reports of the wavelength dependence of SHG from collagen have been inconsistent by showing little spectral dependence, a monotonic decrease with wavelength, or more complicated oscillatory responses [10–13]. These discrepancies may have occurred because of incomplete characterization of all the experimental factors [e.g., pulse widths, photomultiplier tube (PMT) quantum efficiency, lens and filter transmission]. Additionally, the specific roles of primary (loss of laser) and secondary filter (loss of signal) effects were not rigorously considered. For example, scattering coefficients at the laser and SHG wavelengths were not measured in these studies. This is important as Monte Carlo simulations based on these properties are necessary to properly decouple the SHG properties from scattering when the tissue is of sufficient thickness to support one or more scattering events. Moreover, the initial emission directionality, FSHG/BSHG, must also be considered as this is further coupled with scattering, influencing the measured forward and backward propagating signals. We also note that imaging thin sections (~5–10 μm) can lead to artifacts as opposed to imaging intact 3D sections that better represent the tissue and avoid boundary effects.

In this Letter, we address this outstanding question of SHG wavelength dependence in tissue by incorporating all these elements into the same analysis using murine tendon and human ovarian cancer tissues. Additionally, we extend the measurements to longer wavelengths than the previous studies using both a Ti:sapphire laser along with a synchronously pumped optical parametric oscillator (OPO) over the 780–1230 nm range. We find that the longer wavelength excitation in tissue is less efficient for SHG microscopy as the reduced scattering is a smaller effecter than the decreased conversion efficiency.

The wavelength dependence of the SHG signal from collagen fibers was measured and analyzed using a combination of SHG imaging microscopy and Monte Carlo simulations, both of which have been previously described [5,14]. SHG images were acquired in the forward propagating direction using circular polarization with no signal polarization analysis. The measurements were independent of specimen orientation. The effective numerical aperture (NA) of the system was approximately maintained over the wavelength range by adjustment of the spot size at the objective back aperture. In the simulations, excitation photons were launched toward the focal point as defined by the NA of the objective (0.8) and included the loss due to scattering based on μs at the laser wavelength. The SHG collection was modeled by launching photons from the focal point and determining the fraction collected in the forward and backward detector geometries including the respective NAs (0.9 and 0.8) and optical properties at λSHG [15].

Mouse tail tendon was used to investigate the relationship between the SHG signal strength of collagen and excitation wavelength as the uniformity makes it an ideal sample for characterization purposes. Tendons were extracted from wild-type mice and fixed in formalin for 24 h then stored in PBS at 4°C. Tendons were acquired from three mice and three samples were imaged from each. Three measurements were taken at each wavelength for both SHG and optical property measurements. We also examined the wavelength dependence of SHG and optical properties of ovarian malignancies, where the stroma is comprised primarily of dense collagen. These were acquired under an approved IRB UW-Madison protocol. The scattering coefficient, μs, and anisotropy, g, were measured at both the laser and SHG wavelengths using a combined measurement of goniometry and on-axis attenuation as described previously [16]. The pulse width was measured using a commercial autocorrelator prior to entering the microscope following transmission through a Faraday isolator, electro-optic modulator and polarization control optics. It is assumed that pulse broadening due to glass within the microscope is minimal at these long wavelengths especially given the moderate bandwidth (~10 nm).

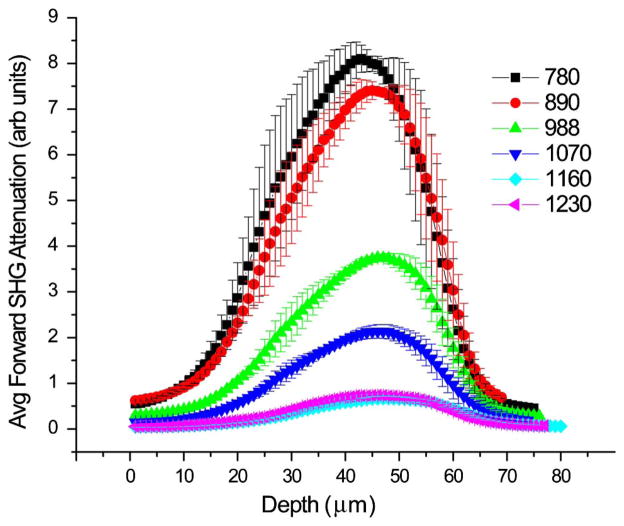

Figure 1 shows representative attenuation curves obtained from SHG imaging of mouse tail tendon (~70 μm in thickness) over the range of 780–1230 nm. The upper and lower wavelength ranges are limited by optical transmission in the microscope. At a given wavelength, we have shown that this response largely arises from the square of the primary filter effect and relative SHG conversion efficiency [5]. Each curve has been normalized in terms of the inverse excitation power squared (measured at the focus) and pulse width and detector efficiency at each wavelength. The position of the peak of each curve is defined by a combination of factors including scattering of the laser and fully collecting the scattered SHG signal within the condenser aperture. We note there is a strong decrease in relative intensity at increasing wavelengths, where the maximum response decreases by over ~10 fold between 780 and 1230 nm. Unfixed tendons yielded similar results.

Fig. 1.

Representative forward SHG depth response in tendon over a wide wavelength range. Each curve has been accounted for excitation power, pulse width, and PMT detector sensitivity. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean for measurements at three locations of similar thickness.

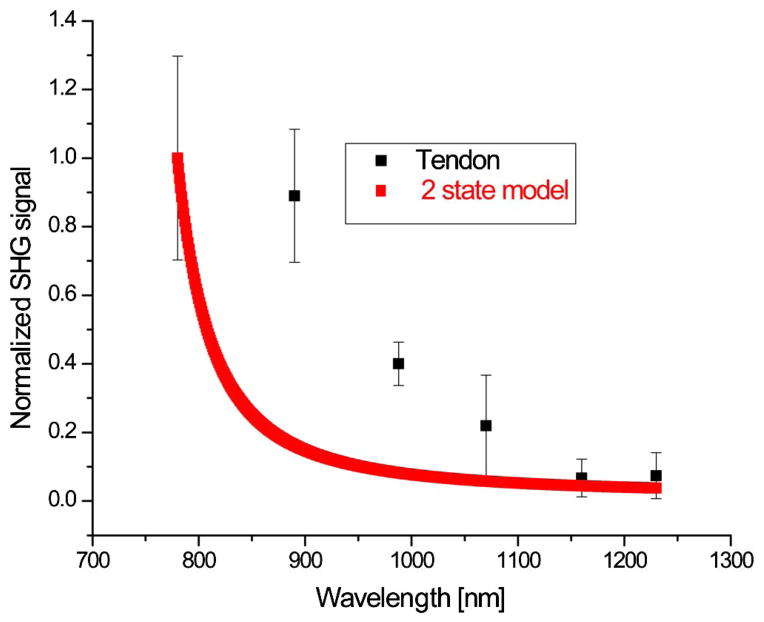

We used Monte Carlo simulation of the emission based on the measured scattering properties (see Table 1) and experimental geometry to decouple the effects of scattering from the SHG conversion efficiency. Figure 2 shows the resulting extracted wavelength conversion efficiency of the SHG intensity from tendon, along with the wavelength dependency of β according to the two-state model, based on the nearest one-photon resonance frequency of ~360 nm. Each point represents the peak of a corresponding depth-resolved SHG attenuation curve and is divided by the forward detection efficiency given by a Monte Carlo simulation of emission given the depth of the peak location and sample thickness. We find that this two-state model is not a good representation of the data, however, where the measured SHG has greater intensity than predicted. The one-photon transitions arising from the collagen molecules are in the 190–220 nm range (corresponding to either π → π* or n → π* transition) [17] and provide an even more inaccurate representation as excitation wavelengths here are further from these resonances (not shown).

Table 1.

Measured Optical Properties of Tissues

| λ [nm] | Rat Tail Tendon

|

Human Ovary

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μs[cm−1] | g | μs[cm−1] | g | |

| 390 | 790 ± 60 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | ||

| 445 | 450 ± 30 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 640 ± 50 | 0.97 ± 0.01 |

| 494 | 380 ± 30 | 0.94 ± 0.02 | 580 ± 70 | 0.98 ± 0.01 |

| 535 | 330 ± 30 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 260 ± 30 | 0.96 ± 0.01 |

| 680 | 280 ± 20 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | ||

| 780 | 240 ± 10 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | ||

| 890 | 250 ± 20 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 220 ± 20 | 0.97 ± 0.01 |

| 988 | 230 ± 20 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 220 ± 28 | 0.97 ± 0.01 |

| 1070 | 220 ± 20 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 210 ± 24 | 0.97 ± 0.01 |

Fig. 2.

SHG strength of tendon as function of wavelength based on a two-state model for comparison.

We also note that wavelength dependence of phase matching is expected to be a relatively small effect. Using the laser and SHG wave vectors and Gouy phase shift, the phase mismatch Δk in the forward direction (limited by dispersion in the refractive index) varies only by ~10% over 780–1230 nm. Moreover, we showed the wavelength dependence of FSHG/BSHG, which is indicative of the phase matching, only slowly increases with wavelength, by about ~30% from 890 to 1230 nm [15]. This further suggests that phase matching of collagen does not significantly contribute to the underlying wavelength dependence. The mismatch between the predicted and experimental data may be due to inaccuracies in the two-state model or different absorption in native collagen and this requires future investigation.

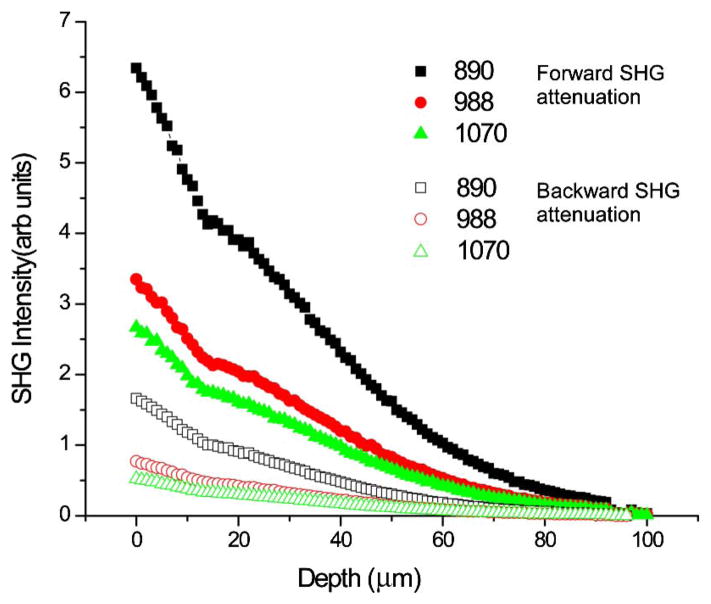

We now consider the SHG attenuation response as a function of wavelength for human ovarian tissue using both the forward and backward collection geometries. These are simulated using the relative β values from Fig. 2 with measured scattering coefficients at the laser and SHG wavelengths (Table 1), and inclusion of FSHG/BSHG which are based on previous results [15]. Figure 3 shows the resulting simulations of the forward and backward attenuations, where the relative intensities decrease with increasing wavelength. In analogy to tendon, these simulations show the gain in measured signal strength at longer wavelengths due to reduced scattering is overcome by the decrease in SHG conversion efficiency at longer wavelengths.

Fig. 3.

Simulation of signal attenuation in ovarian tissue. The forward and backward signals are shown with solid and open circles, respectively.

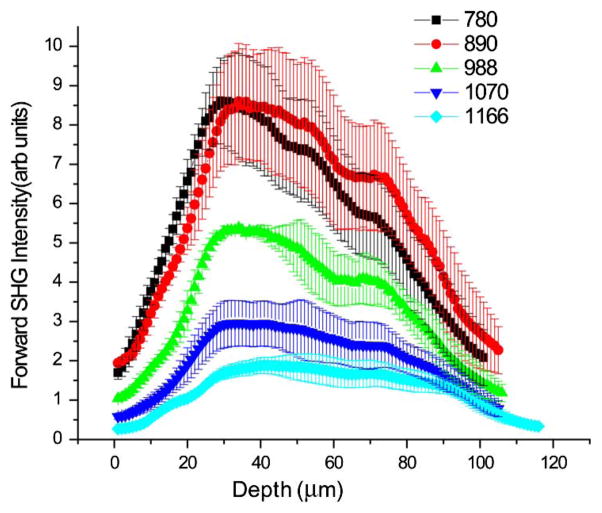

For comparison, Fig. 4 shows experimental data of human adenocarcinoma ovarian cancer across this same excitation range (780–1160 nm). The decrease in measured intensity at longer wavelengths is consistent with the simulations and our conclusions that shorter wavelength SHG excitation is more efficient. This has further implications for backward detected SHG. We have previously shown that FSHG/BSHG gradually increases at longer wavelengths [15]. There is also reduced scattering that can redirect forward emitted photons, thus backward detected SHG will further decrease in intensity relative to forward detected measurements.

Fig. 4.

SHG wavelength-dependent experimental attenuation curves for adenocarcinoma of human ovary.

As the 780 nm excitation wavelength was the most efficient for both tendon and ovary, one could then question if SHG measurements should be performed at even shorter wavelengths if this trend continues. We suggest this is not the case for several reasons. Longer wavelengths will have advantages in performing polarization measurements where usable tissue thicknesses are governed by the scattering of both the laser and emitted SHG signal [18]. Moreover, longer wavelengths provide better tissue viability. Experimental considerations also dictate the use of 800–890 nm wavelengths. Commonly used GaAsP PMTs demonstrate a significant decrease at wavelengths below ~400 nm. Moreover, the transmission of glass decreases in this range.

In summary, we have investigated the wavelength dependence of the SHG conversion efficiency and optical scattering in 3D tissues. We found that, despite reduced scattering at longer wavelengths, SHG imaging microscopy of collagenous tissues is still best performed at shorter wavelengths, as β rapidly decreases at longer wavelengths, where we observed an approximately 10 fold decrease between 780 and 1230 nm. The nature of the dependence requires further study. We also show that for imaging 3D tissues, the experimental design needs to consider all the contributing factors of the SHG creation and optical scattering and that Monte Carlo simulations are necessary to decouple these effects.

Acknowledgments

G. H. acknowledges support from a Leifur Eiríksson scholarship. We gratefully acknowledge NIH R01 CA136590-01A1, and NSF CBET 0959525 grant. K. T. acknowledges support under NIH 5T32CA009206-34.

References

- 1.Campagnola PJ, Dong CY. Laser Photon Rev. 2011;5:13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Provenzano PP, Inman DR, Eliceiri KW, Knittel JG, Yan L, Rueden CT, White JG, Keely PJ. BMC Med. 2008;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nadiarnykh O, Lacomb RB, Brewer MA, Campagnola PJ. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strupler M, Pena AM, Hernest M, Tharaux PL, Martin JL, Beaurepaire E, Schanne-Klein MC. Opt Express. 2007;15:4054. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.004054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacomb R, Nadiarnykh O, Campagnola PJ. Biophys J. 2008;94:4504. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.114405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacomb R, Nadiarnykh O, Townsend SS, Campagnola PJ. Opt Commun. 2008;281:1823. doi: 10.1016/j.optcom.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mertz J, Moreaux L. Opt Commun. 2001;196:325. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oudar JL, Chemla DS. J Chem Phys. 1977;66:2664. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards-Kortum R, Sevick-Muraca E. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1996;47:555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.47.1.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Theodossiou TA, Thrasivoulou C, Ekwobi C, Becker DL. Biophys J. 2006;91:4665. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zipfel WR, Williams RM, Webb WW. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1369. doi: 10.1038/nbt899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zoumi A, Yeh A, Tromberg BJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172368799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen M, Zhao J, Zeng H, Tang S. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18:031109. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.3.031109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Nadiarynkh O, Plotnikov S, Campagnola PJ. Nat Protocols. 2012;7:654. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall G, Eliceiri KW, Campagnola PJ. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18:116008. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.11.116008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall G, Jacques SL, Eliceiri KW, Campagnola PJ. Biomed Opt Express. 2012;3:2707. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.002707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caldwell JW, Applequist J. Biopolymers. 1984;23:1891. doi: 10.1002/bip.360231006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadiarnykh O, Campagnola PJ. Opt Express. 2009;17:5794. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.005794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]