Abstract

2-Hydroxyethylphosphonate dioxygenase (HEPD) and methylphosphonate synthase (MPnS) are non-heme iron oxygenases that both catalyze the carbon-carbon bond cleavage of 2-hydroxyethylphosphonate but generate different products. Substrate labeling experiments led to a mechanistic hypothesis in which the fate of a common intermediate determined product identity. We report here the generation of a bifunctional mutant of HEPD (E176H) that exhibits the activity of both HEPD and MPnS. The product distribution of the mutant is sensitive to a substrate isotope effect, consistent with an isotope-sensitive branching mechanism involving a common intermediate. The X-ray structure of the mutant was determined and suggested that the introduced histidine does not coordinate the active site metal, unlike the iron-binding glutamate it replaced.

Phosphonate natural products are synthesized by a wide variety of organisms and can fulfill structural roles as well as exhibit diverse bioactivities.1–3 One example of the latter are the herbicidal phosphinothricin-containing peptides produced by soil-dwelling Streptomyces. In elucidating the phosphinothricin tripeptide biosynthetic pathway, a number of unusual transformations were discovered.4 One such unprecedented reaction is the carbon-carbon bond cleavage of 2-hydroxyethylphosphonate (2-HEP) catalyzed by the non-heme iron enzyme 2-hydroxyethylphosphonate dioxygenase (HEPD) in an Fe(II)- and O2-dependent manner to generate hydroxymethylphosphonate (HMP) and formate (Scheme 1A).4,5 An enzyme with distant sequence homology to HEPD was recently found to produce methylphosphonate (MPn) in the aquatic archaeon Nitrosopumilus maritimus (Scheme 1B).6,7 This enzyme was therefore named methylphosphonate synthase (MPnS); MPn is likely used as a polar headgroup to decorate exopolysaccharides of N. maritimus.6

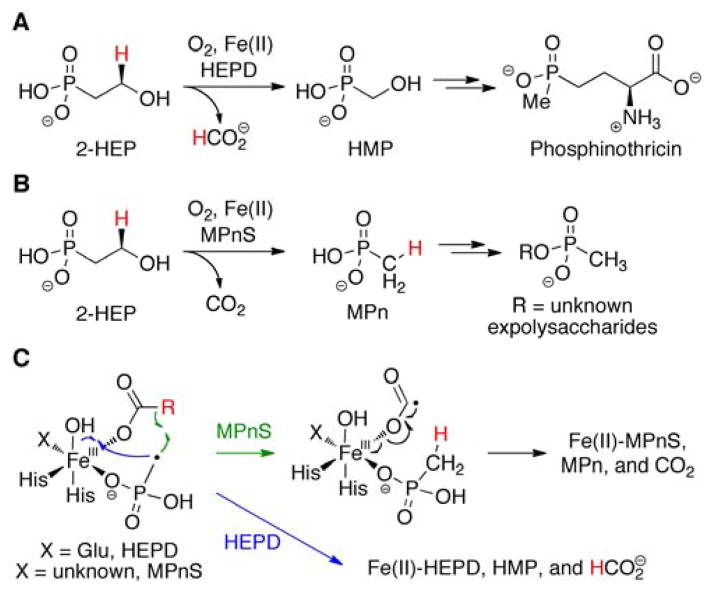

Scheme 1.

Reactions catalyzed by (A) HEPD and (B) MPnS. (C) A proposed common intermediate in the reactions depicted in panels A and B.

Labeling experiments with HEPD demonstrated that the hydrogen atom from the pro-R position at C2 of 2-HEP was incorporated into formate,8 whereas MPnS transfers the same hydrogen into MPn (Scheme 1).7 Despite their different biological contexts and products, a consensus mechanism was proposed in which a methylphosphonate radical would either react with a ferric-hydroxide to make HMP or abstract a hydrogen atom from formate to generate MPn and a formyl radical anion (Scheme 1C).7 This strong reductant (E1/2 −1.85 V vs. NHE at pH 7)9,10 has been previously invoked in the mechanism of class III ribonucleotide reductases,11–13 and in MPnS catalysis could reduce the Fe(III) to the Fe(II) resting state with concomitant release of CO2 (Scheme 1C). Whereas the cocrystal structure of Cd(II)-HEPD has been solved,5 efforts to crystallize MPnS have not been successful, and hence structural information at present is not available to help explain the different outcomes of catalysis by the two proteins. A sequence alignment illustrated that a key difference between the two enzymes is the apparent absence of a Glu ligand in MPnS (Figure S1).7 In HEPD, this Glu176 is part of the canonical 2-His-1-carboxylate facial triad14 that coordinates the Fe(II). As part of a site-directed mutagenesis effort to glean additional insight into catalysis,5,8,15 in this study we generated HEPD mutants of Glu176. Characterization of one of these mutants, HEPD-E176H, has provided direct support for a methylphosphonate radical as a common late stage intermediate in catalysis leading to HMP or MPn.

HEPD-E176H was constructed, expressed, and purified as reported previously for other variants (see Supporting Information).5,15 The protein was reconstituted anaerobically with varying equivalents of Fe(II), and the activity of the mutant towards 2-HEP was assessed using a continuous, steady-state assay with a Clark-type O2 electrode.8 HEPD-E176H required more than 1 equivalent of Fe(II) to attain maximal activity (Figure S2), in contrast to wild type (wt) HEPD.5 Use of the O2 electrode also enabled the determination of kinetic parameters for oxidation of both 2-HEP and 2-[2-2H2]-HEP under conditions where the enzyme was saturated with Fe(II) (Table 1, Figure S3). Overall, HEPD-E176H exhibited similar kinetic parameters as wt HEPD with both substrates, illustrating that the steps that govern the overall kinetics with respect to 2-HEP were likely similar in both enzymes.

Table 1.

Steady-state Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters with wt HEPD and HEPD-E176H.

| Protein | Substrate | kcat (s−1) | Km,HEP (μM) | KIE, kcat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt HEPD | 2-HEP | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 8 ± 1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| 2-[2-2H2]-HEP | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 10 ± 2 | ||

| HEPD-E176H | 2-HEP | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 23 ± 3 | 1.5. ± 0.1 |

| 2-[2-2H2]-HEP | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 25 ± 2 |

The reaction of HEPD-E176H with 2-HEP was analyzed by 31P NMR spectroscopy, which showed complete consumption of starting material and, surprisingly, the appearance of two species (Figure 1A). The signal at 17 ppm was identified as HMP by spiking with the authentic compound. The additional resonance at 24 ppm was unexpected. Spiking the sample with authentic MPn revealed that MPn produced the unanticipated resonance. The E176H mutation thus confers partial MPnS-like activity to HEPD. Quantifying product formation as a function of O2 consumption demonstrated that the two processes were coupled, with a ratio of 1.2 ± 0.1 of molecules of product formed and O2 consumed (see SI).

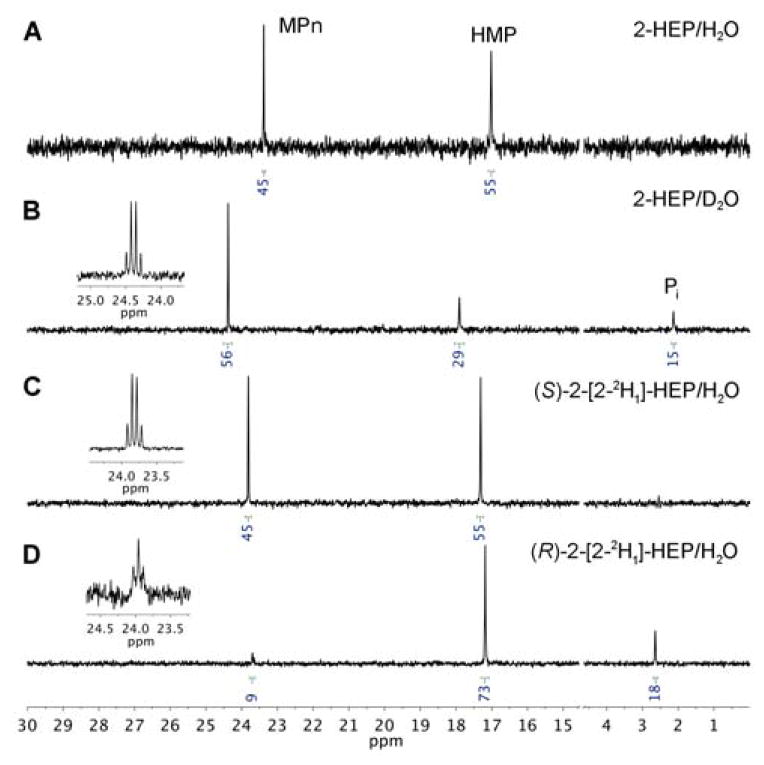

Figure 1.

1H-decoupled 31P NMR spectra of the reaction of HEPD-E176H with (A) 2-HEP in buffered H2O, (B) 2-HEP in buffered D2O, (C) (S)-2-[2-2H1]-HEP in buffered H2O, and (D) (R)-2-[2-2H1]-HEP in buffered H2O. Inset: the MPn signal from 1H-coupled 31P NMR spectrum of each reaction; 31P NMR chemical shifts of phosphonates are very sensitive to solvent and pH, accounting for the small differences between spectra.

Previous studies have suggested that both HEPD and MPnS generate a methylphosphonate radical.7,8,16,17 In HEPD-E176H this intermediate might be partitioning between reaction with the ferric hydroxide to afford HMP (Scheme 1C, blue arrows) and abstraction of the hydrogen atom of the nearby formate to generate MPn (green arrows). If the hypothesis of a common late stage methylphosphonate radical is correct, then use of appropriately deuterium-labeled substrate might affect the product distribution of HEPD-E176H, because the reaction with a deuterium labeled formate could face an increased barrier that would change the partitioning ratio.

Hence, the reaction of HEPD-E176H was carried out under a set of different conditions. The enzyme was first incubated with 2-HEP in buffered D2O. Consistent with previous findings with wt HEPD, the methylphosphonate produced did not contain any deuterium as shown by the quartet splitting of the 1H-coupled 31P NMR signal as a consequence of coupling to three equivalent methyl hydrogen atoms. (Figure 1B, inset). This observation is consistent with a proton from C2 of 2-HEP having migrated to the methyl group of MPn, via the intermediacy of formate (Scheme 1C).7 Next (R)-2-[2-2H1]-HEP or (S)-2-[2-2H1]-HEP were separately incubated with the enzyme in buffered H2O. The 1H-coupled 31P NMR spectrum of the reaction with (S)-2-[2-2H1]-HEP displayed again a quartet (Figure 1C, inset), but the spectrum of the reaction with (R)-2-[2-2H1]-HEP exhibited a triplet (Figure 1D, inset). Thus, the methyl group of MPn produced by HEPD-H176H contains the hydrogen that was originally in the pro-R position at C2 of 2-HEP. An additional resonance near 3 ppm is produced by inorganic phosphate (Pi) as shown by spiking with authentic material. Pi is the result of oxidation of HMP by the mutant enzyme (Figure S4), as previously also reported for wt HEPD.18

In addition to verification that the pro-R hydrogen atom migrates from C2 of 2-HEP to the methyl group of MPn, the data also demonstrate a striking change in product distribution. The 1H-decoupled 31P NMR spectra of the products formed with 2-HEP in D2O and (S)-2-[2-2H1]-HEP in H2O had similar MPn to (HMP+Pi) ratios, but the reaction with (R)-2-[2-2H1]-HEP produced substantially less MPn compared to HMP and Pi (Figure 1). The observation that the product distribution is sensitive to the stereoselective incorporation of a deuterium atom strongly implies that the pro-R hydrogen atom of C2 of 2-HEP moves at the branch-point for formation of the two products. In turn, this finding is fully consistent with that branch point being a methylphosphonate radical that would experience a strong selection against deuterium atom abstraction from formate, since the pro-R hydrogen at C2 of 2-HEP ends up in formate.8

The roughly equivalent amounts of (HMP+Pi) and MPn produced by the E176H mutant suggests that the energy barriers for these two processes are roughly equal in height with unlabeled substrate. Abstraction of a deuterium atom from formate increases the energy barrier for MPn formation and therefore more HEPD activity is observed when the reaction was carried out with (R)-2-[2-2H1]-HEP. Based on the product ratios, the substrate kinetic isotope effect (KIE) for this step is ~10, consistent with a hydrogen-atom transfer process. Although we were unable to determine the individual Km values for 2-HEP for production of MPn or HMP, the ratio of MPn to HMP was unchanged at varying concentrations of substrate (Table S1), consistent with the branch point occurring after the first irreversible step in the catalytic cycle, which would result in identical Km,2-HEP values for production of HMP and MPn.

Lipoxygenases,19 cytochrome P450s,20–22 non-heme iron enzymes,23 dinuclear iron enzymes,24 and monoterpene cyclases25 have all been reported to generate mixtures of products that change in an isotope-sensitive manner. HEPD-E176H exhibits isotope-sensitive branching with a KIE similar to that reported for lipoxygenases, aliphatic hydroxylases, and P450s (KIEs of 7–12) that are believed to be associated with hydrogen atom abstraction steps.19–21,23 HEPD-E176H is unique in that it combines the activity of two different enzymes (each of which generates only a single product) in one scaffold, and that the competition is between two fundamentally different reactions (Scheme 1), rather than the more common change in site-selectivity that still involves the same overall transformation.

The reaction of HEPD-E176H with 2-HEP in D2O reproducibly led to slightly increased MPnS activity compared to the identical reaction conducted in H2O (Table S2). One possible explanation is that the higher viscosity of D2O might influence a conformational change in HEPD-E176H that affects the branching ratio. However, conducting the reaction in H2O in the presence of the microviscogens glycerol or sucrose did not increase the ratio of MPn formation (Table S2). Another possibility is that the altered pKa values of reactants or surrounding residues in D2O compared to H2O result in different fractional protonation states in the two solvents.26 To test this, the product distribution was monitored in the pH window 6.5–8.5, but no differences were observed (Table S3). We also investigated whether addition of formate at the start of the reaction might skew the reaction towards increased MPnS activity. However, when the reaction was supplemented with formate (1 mM), a similar ratio of MPn to HMP was observed as in the absence of formate (Table S2). The product distribution was also insensitive to the amount of Fe(II) used to reconstitute HEPD-E176H (Table S4). One other potential explanation for the slightly different amounts of MPn formed in H2O and D2O is that a proton transfer is involved in MPn formation, but we do not have direct evidence for this hypothesis and therefore at present, the origin of the small but noticeable solvent isotope effect on the product distribution is not clear.

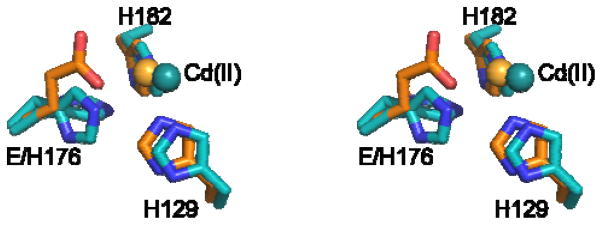

To investigate whether the active site of HEPD-E176H might provide insights into its bifunctional activity, HEPD-E176H was crystallized. As reported previously for wt HEPD,5 Cd(II) was required in the precipitant solution, and the structure of the mutant was solved to 1.75 Å. The overall fold of the protein was not perturbed. The structure exhibited ill-defined electron density for His176 (Figure 2) suggesting multiple conformations for this residue, in contrast to the well-defined electron densities for the native histidines that are conformationally anchored by binding to Cd(II). Unlike the single conformation of Glu176 observed in wt HEPD, the multiple conformers of His176 imply that it does not bind the active site metal. Lack of coordination by His176 is also supported by the distances of its Nε to the Cd(II) in the two conformations (3.7 and 5.5 Å), and by the observation that the metal ion in HEPD-E176H is displaced relative to its position in the structure of wt HEPD in complex with Cd(II) (Figure 2). The structure may also explain why more than one equivalent of Fe(II) was necessary to reconstitute full activity of HEPD-E176H. Attempts to obtain structures of HEPD-E176H in complex with 2-HEP or other divalent metals were unsuccessful. With the caveat that Cd(II) is not a very good substitute for Fe(II), these observations suggest that HEPD-E176H operates as a 2-His enzyme, similar to the non-heme iron halogenase SyrB2 in syringomycin E biosynthesis.27

Figure 2.

Stereo-view of Cd(II)•HEPD-E176H (cyan) superimposed on Cd(II)•wt HEPD (orange). The Cd(II) displacement is illustrated. The multiple conformations adopted by His176 in the mutant enzyme are shown.

Because the residues that bind the phosphonate moiety of 2-HEP (e.g. Arg90 and Asn126)15 maintain conformations that are very close to those in the wt enzyme, we predict that 2-HEP would bind to the mutant enzyme in the bidentate fashion that has been previously observed in wt HEPD.5 Both alignment of the primary sequences and homology modeling28 suggested that the architectures of the active sites of HEPD and MPnS are similar (Figures S1 and S5). While the Fe(II)-coordinating His residues are conserved between the two proteins, MPnS appears to have a Gln in lieu of Glu176. However, mutation of Glu176 in HEPD to Gln or Asp did not yield MPnS activity as HMP was the only product observed (Figure S6). Structural elucidation of MPnS might help clarify the role of this residue.

In summary, the collective results detailed herein strongly bolster the hypothesis that HEPD and MPnS share a common mechanism with a late branch point governing product determination. Furthermore, the data are fully consistent with this branch point being a methylphosphonate radical. Unraveling whether the earlier intermediates are also similar in the two enzymes will require further investigations through either 18O kinetic isotope effect studies29 or spectroscopic characterization of trapped intermediates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (P01 GM077596 to W.A.V. and S.K.N.). NMR spectra were recorded on a 600 MHz NMR spectrometer purchased with support from NIH S10 RR028833.

Footnotes

Experimental procedures, Supporting Figures, kinetic data, and NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. Coordinates for HEPD-E176H were deposited to the Protein Data Bank as code 4YAR.

References

- 1.Peck SC, van der Donk WA. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:580. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metcalf WW, van der Donk WA. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.091707.100215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGrath JW, Chin JP, Quinn JP. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:412. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blodgett JA, Thomas PM, Li G, Velasquez JE, van der Donk WA, Kelleher NL, Metcalf WW. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:480. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cicchillo RM, Zhang H, Blodgett JAV, Whitteck JT, Li G, Nair SK, van der Donk WA, Metcalf WW. Nature. 2009;459:871. doi: 10.1038/nature07972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metcalf WW, Griffin BM, Cicchillo RM, Gao J, Janga S, Cooke HA, Circello BT, Evans BS, Martens-Habbena W, Stahl DA, van der Donk WA. Science. 2012;337:1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1219875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooke HA, Peck SC, Evans BS, van der Donk WA. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:15660. doi: 10.1021/ja306777w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitteck JT, Malova P, Peck SC, Cicchillo RM, Hammerschmidt F, van der Donk WA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4236. doi: 10.1021/ja1113326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stubbe J, van der Donk WA. Chem Rev. 1998;98:705. doi: 10.1021/cr980059c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surdhar PS, Mezyk SP, Armstrong DA. J Phys Chem B. 1989;93:3360. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulliez E, Ollagnier S, Fontecave M, Eliasson R, Reichard P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eklund H, Fontecave M. Structure. 1999;7:R257. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)80019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei Y, Mathies G, Yokoyama K, Chen J, Griffin RG, Stubbe J. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9001. doi: 10.1021/ja5030194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koehntop KD, Emerson JP, Que L., Jr J Biol Inorg Chem. 2005;10:87. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0624-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peck SC, Cooke HA, Cicchillo RM, Malova P, Hammerschmidt F, Nair SK, van der Donk WA. Biochemistry. 2011;50:6598. doi: 10.1021/bi200804r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirao H, Morokuma K. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:17901. doi: 10.1021/ja108174d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du L, Gao J, Liu Y, Liu C. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:11837. doi: 10.1021/jp305454m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitteck JT, Cicchillo RM, van der Donk WA. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16225. doi: 10.1021/ja906238r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacquot C, Wecksler AT, McGinley CM, Segraves EN, Holman TR, van der Donk WA. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7295. doi: 10.1021/bi800308q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones JP, Korzekwa KR, Rettie AE, Trager WF. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:7074. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wüst M, Croteau RB. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1820. doi: 10.1021/bi011717h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Y, He X, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Biochemistry. 2006;45:533. doi: 10.1021/bi051840z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavon JA, Fitzpatrick PF. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16414. doi: 10.1021/ja0562651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell KH, Rogge CE, Gierahn T, Fox BG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0636619100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Croteau RB, Wheeler CJ, Cane DE, Ebert R, Ha HJ. Biochemistry. 1987;26:5383. doi: 10.1021/bi00391a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jencks WP. Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology. Dover; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blasiak LC, Vaillancourt FH, Walsh CT, Drennan CL. Nature. 2006;440:368. doi: 10.1038/nature04544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJE. Nat Protocols. 2009;4:363. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roth JP. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:399. doi: 10.1021/ar800169z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.