Abstract

Introduction:

Conscious sedation has traditionally been used for laparoscopic tubal ligation. General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation may be associated with side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, cough, and dizziness, whereas sedation offers the advantage of having the patient awake and breathing spontaneously. Until now, only diagnostic laparoscopy and minor surgical procedures have been performed in patients under conscious sedation.

Case Description:

Our report describes 5 cases of laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy successfully performed with the aid of conventional-diameter multifunctional instruments in patients under local anesthesia. Totally intravenous sedation was provided by the continuous infusion of propofol and remifentanil, administered through a workstation that uses pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic models to titrate each drug, as well as monitoring tools for levels of conscious sedation and local anesthesia. We have labelled our current procedure with the acronym OLICS (Operative Laparoscopy in Conscious Sedation). Four of the patients had mono- or bilateral ovarian cysts and 1 patient, with the BRCA1 gene mutation and a family history of ovarian cancer, had normal ovaries. Insufflation time ranged from 19 to 25 minutes. All patients maintained spontaneous breathing throughout the surgical procedure, and no episodes of hypotension or bradycardia occurred. Optimal pain control was obtained in all cases. During the hospital stay, the patients did not need further analgesic drugs. All the women reported high or very high satisfaction and were discharged within 18 hours of the procedure.

Discussion and Conclusion:

Salpingo-oophorectomy in conscious sedation is safe and feasible and avoids the complications of general anesthesia. It can be offered to well-motivated patients without a history of pelvic surgery and low to normal body mass index.

Keywords: Operative laparoscopy in conscious sedation, Ovarian cysts, Salpingo-oophorectomy

INTRODUCTION

Minimally invasive surgery provides effective treatment of surgical diseases with lower risk of access-related morbidity. In the past 2 decades, technological advancements have helped to further decrease morbidity, thus improving the acceptability of surgical treatments. At the beginning of the 1990s, a new technique, termed minilaparoscopy, was developed, in which optics and instruments smaller than 5 mm in diameter are used.1,2 The main advantages of instruments with reduced diameter are decreased surgical trauma, more comfortable postoperative recovery, and the possibility of performing laparoscopy under sedation.3,4 Sedation offers the advantage of having the patient awake, oriented, and breathing spontaneously.5 Moreover, the fast-track recovery is associated with decreased costs, avoiding the need for keeping patients in the postanesthesia care unit.6 Until now, only diagnostic laparoscopy and minor surgical treatments have been performed with conscious sedation, such as cauterization of endometriotic foci, adhesiolysis, tubal sterilization, appendectomy, ovarian drilling, ovarian biopsy, and assisted reproduction procedures, such as gamete intrafallopian transfer.3,5–11 We found no reports of laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy in patients under sedation. We report 5 cases of laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy successfully performed at our center with the aid of conventional-diameter multifunctional instruments in patients under local anesthesia and a totally intravenous sedation protocol, based on continuous infusion of propofol and remifentanil, 2 short-acting drugs, administered through a workstation according to pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models for titration of each drug, as well as monitoring tools to track levels of conscious sedation and pain.12–14

CASES AND TECHNIQUE

Sedation and Analgesia Protocol

Upon arrival in the operating room, the patient received midazolam 2 mg intravenously. Standard monitoring was performed by continuous electrocardiography (DII - second limb lead), pulse-oximetry, capnography, and noninvasive blood pressure. Propofol and remifentanil were administered with the SmartPilot View system (Dräger, Hemmel Hempstead, UK), with software based on a PK-PD model that calculates drug concentrations, visualizes the effects and interactions between the 2 drugs, and shows the anesthetist the stage of sedation at which the patient is and will be.15 Beyond the parameters measured (pulse rate and blood pressure), the software also monitors depth of sedation by bispectral index, an EEG parameter, as well as the synergistic effects of hypnotics and analgesics, by instant calculation of the noxious stimulus response index (NSRI).16 Intraoperative pain was evaluated by using the visual analog scale (VAS). Before surgical procedures, the infusions were started at a rate of 2 mg/kg per hour (range, 1.5–3 mg/kg per hour) for propofol and at 0.05 μg/kg per minute (range, 0.05–0.1 μg/kg per minute) for remifentanil. The drugs were titrated stepwise until achievement of the desired level of sedation and analgesia. These infusions corresponded to effect site concentrations of 0.5–1.5 μg/mL for propofol and 1–2.5 ng/mL for remifentanil. The depth of sedation was increased whenever necessary during the operation, such as for trocar insertions and peritoneum distension. Supplemental oxygen per face mask was provided at deeper levels of sedation. Postoperative analgesia was obtained with paracetamol 1 g, tramadol 100 mg, and ondansetron 4 mg.

VAS monitoring was planned at the time of local anesthesia and all painful operational times (trocar insertions and induction of pneumoperitoneum), at the end of the procedure, and 30 minutes later. However, when other parameters (bispectral index and NSRI) were used to monitor the surgical procedure in an apparently comfortable patient, we skipped the VAS evaluation for that time point, because the levels of the other parameters were acceptable.

Surgical Procedure

The procedure was similar in all patients. The patient was placed in a low lithotomy position with the arms along the body and was kept comfortable with warm blankets on the upper body. The abdomen and vagina were gently prepared with warmed solutions, and a 14-guage Foley catheter coated with lidocaine gel was placed in the bladder. Mepivacaine (1%, 10 mL) was injected at the 3, 9, and 12-o'clock positions of the cervix. An intrauterine manipulator/injector (Richard Wolf GmbH, Knittlingen, Germany), with a single-tooth tenaculum grasping the cervix, was used to manipulate the uterus. The umbilical area was radially injected with approximately 5 mL 1% mepivacaine and 5 mL 0.5% levobupivacaine; 10 mL 1% mepivacaine and 10 mL 0.5% levobupivacaine were later injected, 1 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine on both sides. Once the pain block was considered sufficient, a 12-mm skin incision was made in the umbilical area, and a trocar was placed by the direct-access technique,17 while the anterior abdominal wall was gently lifted. CO2 insufflation of the peritoneal cavity was performed to a maximum pressure of 8 mm Hg. An 11-mm laparoscope with operative channel (Karl Storz GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany) was used. The patient was placed in a moderate Trendelenburg position. Ancillary trocars were inserted, under laparoscopic guidance, through 5-mm skin incisions, 1 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine on both sides.

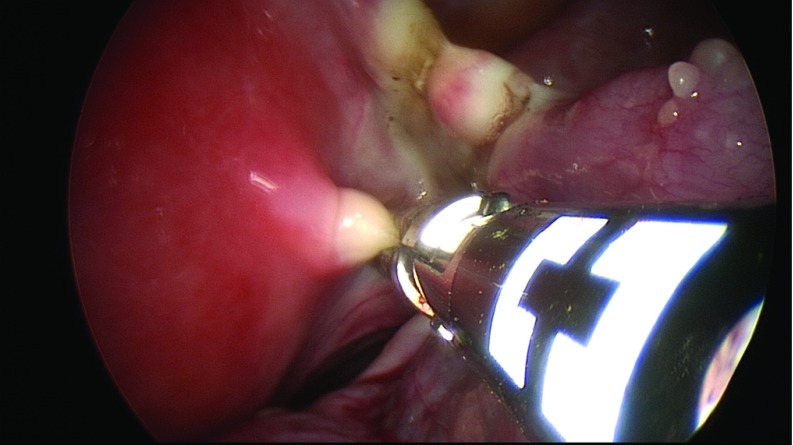

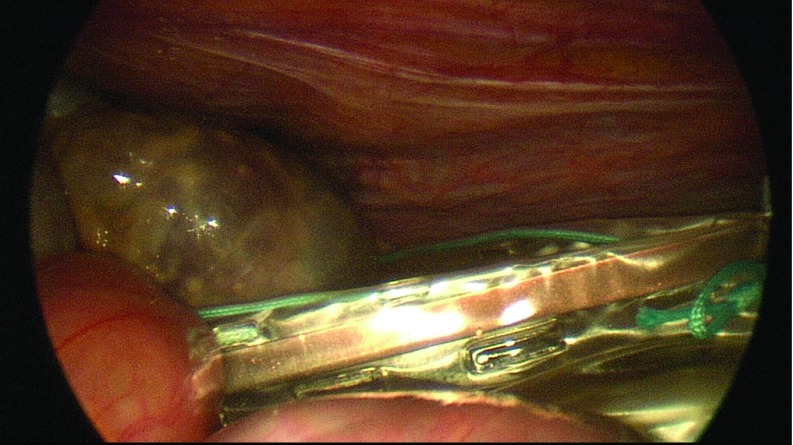

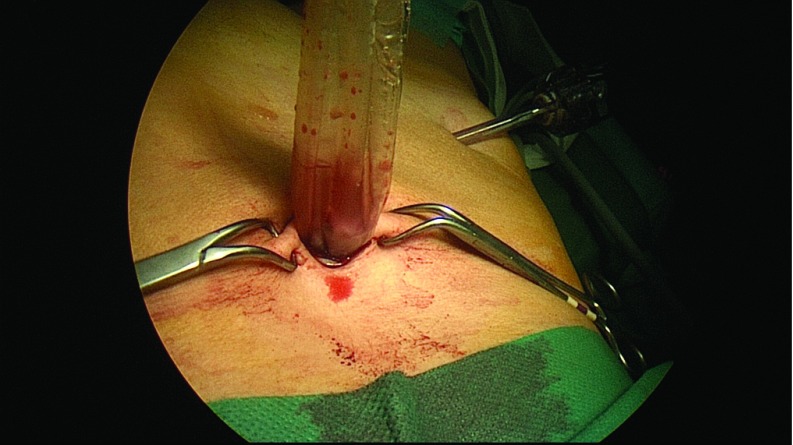

Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed to evaluate the presence of abdominal adhesions, pelvic mass, or ascites. A grasper was inserted through the right ancillary trocar for manipulation of the adnexa. The suction irrigator was introduced through the left ancillary trocar. After the ureters were identified, the adnexa of each side was retracted medially and caudally with the grasper to stretch and outline the infundibulopelvic ligament, the utero-ovarian ligament, and the isthmus of the uterine tube, which were bilaterally coagulated and cut by the 45-cm En-Seal device (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio) or the 44-cm LigaSure device (Covidien, Dublin, Ireland), inserted through the operative channel of the laparoscope (Figure 1). A 10-cm Endobag (Covidien) was inserted through the 12-mm umbilical trocar while a 5-mm optic was inserted via the 5-mm left trocar (Figure 2). The adnexa were then moved into the Endobag with the aid of a grasper inserted through the right 5-mm trocar. Insufflation of CO2 was interrupted, and the umbilical trocar was extracted. The adnexa were successively removed through the umbilical skin incision inside the Endobag18 (Figure 3). Only in patient A were the adnexa extracted by using ring forceps introduced through the umbilical skin incision, after a 5-mm optic had been inserted into the 5-mm left trocar.

Figure 1.

Utero-ovarian ligament and the isthmus of the uterine tube coagulated and cut by a 44-cm multifunctional device introduced via the operative laparoscope.

Figure 2.

Adnexa inserted into the Endobag introduced through the 12-mm umbilical trocar, along with a 5-mm optic inserted through the 5-mm left trocar.

Figure 3.

Adnexa inside the Endobag removed through the umbilical skin incision, without spillage of the liquid contents of the cyst.

Patients

All patients had no systemic diseases, no history of abdominal surgery, endometriosis, or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Their body mass index (BMI) was <25. They were classified as ASA 1 or 2. All underwent a tumor marker evaluation (cancer antigen [Ca]125 and Ca19-9, carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA], human epididymis protein [HE]-4, and α-fetoprotein [AFP]). The patients underwent ultrasonography of the pelvis that showed that all had a normal uterus and no ascites. Patient A had normal ovaries by ultrasonography, whereas the other 4 had ovarian cysts.

Patients' characteristics, diagnosis, and surgical procedures performed are described in Table 1. All patients were thoroughly informed about surgical procedure, sedation protocol and possible related complications, such as the conversion to traditional laparoscopy under general anaesthesia. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. No Institutional Review Board approval was necessary because the anesthesia protocol is routinely used for other surgeries at our institution.

Table 1.

Patients' Characteristics and Surgical Procedures

| Patient | Age | Indication/ Ultrasonographic Diagnosis | Tumor Markers Elevated | Surgical Procedure | Intraoperative Histopathological Evaluation | Intraoperative Diagnosis | Satisfaction Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 47 | BRCA1 gene mutation and a family history of ovarian cancer | No | Prophylactic bilateral SO | No | Normal ovaries | Very high |

| B | 66 | Left 5-cm anechoic ovarian cyst | No | Bilateral SO and adhesiolysis | No | Ovarian cyst with serous liquid content; adhesions between left adnexa and omentum | High |

| C | 41 | Right ovarian mature teratoma | CEA | Right SO, adhesiolysis, and CO2 laser vaporization of endometriosis lesion | Yes | Right ovarian mature teratoma; endometriosis and adhesions between right adnexa and lateral pelvic wall | High |

| D | 54 | Right 5-cm anechoic ovarian cyst | CEA HE4 | Bilateral SO | Yes | Right paratubal cyst | Very high |

| E | 50 | Right 5-cm and left 3-cm anechoic ovarian cysts | No | Bilateral SO | Yes | Bilateral ovarian cysts with serous liquid content | Very high |

Abbreviation: SO, salpingo-oophorectomy.

In patients B and C adhesions between the adnexa and omentum (patient B) or the adnexa and pelvic lateral wall (patient C) were observed at diagnostic laparoscopy. In these cases, before salpingo-oophorectomy, adhesiolysis was performed with scissors inserted through the right trocar.

In patient C, endometriosis between the right adnexa and the pelvic lateral wall was also observed. In this case, CO2 laser vaporization of the endometriosis lesion was performed after salpingo-oophorectomy.

Intraoperative histopathologic evaluation was performed in 2 cases. The results confirmed the clinical diagnosis of an ovarian dermoid cyst in patient C and a paratubal cyst in patient D.

All patients were asked about their level of satisfaction regarding the surgical procedure. They chose 1 of 5 levels of assessment: no satisfaction, low satisfaction, moderate satisfaction, high satisfaction, and very high satisfaction.

Outcome

In all cases, insufflation time ranged from 19 to 25 minutes. No operative complications occurred. No spillage of the liquid contents of the cysts occurred.

All patients maintained spontaneous breathing throughout the surgical procedure, and no episodes of hypotension or bradycardia occurred. Optimal pain control was obtained in all cases, as the highest VAS score reported by each patient was always <4. All patients were able to follow their surgical procedures on the monitor and, during most of the procedure, to speak with the surgeon and the anesthetist, when appropriate. Particularly, during the period of waiting for the pathologist's results, patients C and D remained in conscious sedation and were able to speak with the surgical staff until the results were known and the procedure ended.

No episode of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) occurred. During the hospital stay, the patients did not need any further analgesic drug. All the women reported high or very high satisfaction (Table 1).

Six hours after the surgical procedure, all the patients met the discharge criteria of the Post-anesthetic Discharge Scoring System (PADSS) and were ready to be discharged, but we preferred to have an observational period of 18 h because they were our first patients to have undergone laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy with conscious sedation.

DISCUSSION

In the 1970s, conscious laparoscopy was often performed for tubal ligation, with only local anesthesia and questionable results in pain control.19,20 As the complexity of laparoscopic procedures increased, the use of general anesthesia became the norm. General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation may be associated with side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, cough, and dizziness,10,21 whereas sedation offers the advantage of having the patient awake and breathing spontaneously; furthermore, fast-track recovery may decrease the cost of hospitalization. For these reasons, in the past 2 decades, surgeons have focused their efforts on increasing the number of diseases managed by laparoscopy under sedation and local anesthesia,3,5–11 with a parallel quest to make minimally invasive surgery even more minimal. This quest has led to a decrease in the diameter (minilaparoscopy) or the number (single-port laparoscopy) of trocars.22,23 We found no other report of cases of laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy successfully performed in patients under conscious sedation and local anesthesia. We labelled our current procedure with the acronym OLICS (Operative Laparoscopy in Conscious Sedation).

The success of the procedure was due to several factors. Most important was setting appropriate selection criteria. Body habitus, intra-abdominal adhesions, and general anxiety can be limiting factors.24 To prevent anxiety, we provided a full explanation of the procedure and events surrounding surgery, as recommended in the literature.25 Our hospital staff was well-informed, and one operating room staff member talked to patients while they were being prepared for surgery. During surgery, the drapes and positioning allowed the patients to look into the monitor at all times.

In addition, the quality of sedation was crucial in obtaining full acceptance of the OLICS. In this regard, the combination of propofol as a hypnotic agent and remifentanil as an analgesic and antinociceptive agent represented an optimal choice for tailored sedation. Rapid induction, smooth maintenance, rapid emergence, and adequate pain control, with patients fully awake without side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, and shivering, are the main advantages. Furthermore, the choice of the infusion technique may have played a relevant role. In clinical practice, manual infusion of the boluses leads to multiple peaks and troughs of drug concentrations, possibly inducing more episodes of cardiovascular and respiratory depression. In contrast, infusion based on a PK-PD model provided precise control of drug concentrations and avoided drug overshooting. The SmartPilot View (Dräger) is an assistance system that supports the anesthetist in making decisions; it does not make decisions itself. It is useful in titrating anesthetics to individual variability in responses and to the rapidly changing levels of painful stimulation throughout the surgical procedure. Avoidance of the use of conventional laparoscopic instruments might have limited the operative procedure. Despite the use of trocars and instruments with standard diameters, optimal pain control was obtained in all cases.

However, to make the procedure feasible, the expert and rapid execution of the surgical technique was a key prerequisite. In all cases reported, operative time was approximately 20 minutes. To reach this target required a highly skilled surgeon, a supportive operative staff with adequate laparoscopic experience, and the use of multifunctional instruments and an operative laparoscope. The En-Seal (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc.) and the LigaSure (Covidien) devices were particularly helpful, enabling simultaneous cutting and sealing, providing rapid and excellent vessel sealing with bipolar energy, without collateral thermal damage and excessive smoke. These instruments were inserted into the operative channel of a 12-mm laparoscope. In this way, the ancillary access could be used to mobilize the adnexa and bowel with grasping forceps.

Low-pressure pneumoperitoneum was another key to making the procedure feasible. Use of a maximum CO2 pressure of 8 mm Hg may decrease postoperative abdominal and shoulder-tip pain.25–28 Some surgeons have reported longer operation times and increased hemorrhage with low insufflation pressure; neither occurred in our hands.26 In addition, to reducing pain levels, lower abdominal insufflation pressure was useful in minimizing respiratory and heart complications.29 Therefore, in OLICS, low CO2 pressure is a key element, both for minimizing respiratory and heart disorders and for ensuring optimal intraoperative pain control.24,30

In conclusion, in our 5 cases, salpingo-oophorectomy with conscious sedation was safe and feasible and avoided general anesthesia and its complications. Moreover, all patients in our series reported high or very high satisfaction with the procedure. Thus, laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy with conscious sedation may be offered to well-motivated patients with no history of pelvic surgery and low to normal BMI. This procedure seems promising for patients at risk of ovarian cancer who undergo prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and for those who undergo adnexectomy with frozen examination. A prospective study is necessary to confirm that propofol and remifentanil are safe alternatives to standard anesthetic techniques for laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy.

Contributor Information

Maurizio Rosati, Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Silvia Bramante, Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Fiorella Conti, Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Maria Rizzi, Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Santo Spirito Hospital, Pescara, Italy..

Antonella Frattari, Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Santo Spirito Hospital, Pescara, Italy..

Tullio Spina, Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Santo Spirito Hospital, Pescara, Italy..

References:

- 1. Dordsey JM, Tabb CR. Mini-laparoscopy and fiber optic lasers. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1991;18:613–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Downing BG, Wood C. Initial experience with a new microlaparoscope 2 mm in external diameter. Aust N Z Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;35:202–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Almeida OD, Jr, Val-Gallas JM. Office microlaparoscopy under local anaesthesia in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pelvic pain. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1998;5:407–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Palter SF. Office microlaparoscopy under local anesthesia. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1999;26:109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gupta L, Sinha S, Pande M, Vajifdar H. Ambulatory laparoscopic tubal ligation: a comparison of general anaesthesia with local anaesthesia and sedation. J Anaesth Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27:97–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nezhat C, Main J, Paka C, Soliemannjad R, Parsa MA. Advanced gynecologic laparoscopy in a fast-track ambulatory surgery enter. JSLS. 2014;18:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Almeida OD, Jr, Val-Gallas JM, Rizk B. Appendectomy under local anaesthesia following conscious pain mapping with microlaparoscopy. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:588–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pellicano M, Zullo F, Cappiello F, Di Carlo C, Cirillo D, Nappi C. Minilaparoscopic ovarian biopsy performed under conscious sedation in women with premature ovarian failure. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:817–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pellicano M, Zullo F, Fiorentino A, Tommaselli GA, Palomba S, Nappi C. Conscious sedation versus general anaesthesia for minilaparoscopic gamete intra-Fallopian transfer: a prospective randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2295–2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ikeda F, Vanni D, Vasconcelos A, Podgaec S, Abrão MS. Microlaparoscopy vs. conventional laparoscopy for the management of early-stage pelvic endometriosis: a comparison. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:771–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zullo F, Pellicano M, Zupi E, Guida M, Mastrantonio P, Nappi C. Minilaparoscopic ovarian drilling under local anesthesia in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:376–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li M, Mei W, Wang P, et al. Propofol reduces early post-operative pain after gynecological laparoscopy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bouillon TW. Hypnotic and opioid anesthetic drug interactions on the CNS, focus on response surface modeling. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;182:471–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bouillon TW, Bruhn J, Radulescu L, et al. Pharmacodynamic interaction between propofol and remifentanil regarding hypnosis, tolerance of laryngoscopy, bispectral index, and electroencephalographic approximate entropy. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1353–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sahinovic MM, Absalom AR, Struys MM. Administration and monitoring of intravenous anesthetics. Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2010;23:734–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Luginbühl M, Schumacher PM, Struys M. Noxious Stimulation Response Index: a novel anesthetic state index based on hypnotic-opioid interaction. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:872–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jacobson MT, Osias J, Bizhang R, et al. The direct trocar technique: an alternative approach to abdominal entry for laparoscopy. JSLS. 2002;6:169–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nezhat CR, Kalyoncu S, Nezhat CH, Johnson E, Berlanda N, Nezhat F. Laparoscopic management of ovarian dermoid cysts: ten years' experience. JSLS. 1999;3:179–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wheeless CR., Jr Outpatient laparoscope sterilization under local anesthesia. Obstet Gynecol. 1972;39:767–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fishburne J, Jr, Omran K, Hulka J, Mercer J, Edelman D. Laparoscopic tubal clip sterilization under local anesthesia. Fertil Steril. 1974;25:762–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Macario A, Chang PC, Stempel D, Brock-Utne JG. A cost analysis of the LMA for elective surgery in adult outpatients. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gargiulo AR, Nezhat C. Robot-assisted laparoscopy, natural orifice transluminal endoscopy, and single-site laparoscopy in reproductive surgery. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29:155–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nezhat C, Datta MS, Defazio A, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Natural orifice-assisted laparoscopic appendicectomy. JSLS. 2009;13:14–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yunker A, Steege J. Practical guide to laparoscopic pain mapping. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Demco L. Complications of microlaparoscopy and awake laparoscopy. JSLS. 2003;7:141–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Topçu HO, Cavkaytar S, Kokanal K, Guzel AI, Islimye M, Doganay M. A prospective randomized trial of postoperative pain following different insufflation pressures during gynecologic laparoscopy. Eur J Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bogani G, Uccella S, Cromi A, et al. Low vs standard pneumoperitoneum pressure during laparoscopic hysterectomy: prospective randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:466–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hua J, Gong J, Yao L, Zhou B, Song Z. Low-pressure versus standard-pressure pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2014;208:143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fletcher SJ. Hemodynamic consequences of high- and low-pressure capnoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:596–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gerges FJ, Kanazi GE, Jabbour-Khoury SI. Anesthesia for laparoscopy: a review. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18:67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]