Abstract

Background

Nonvascularized autologous bone grafts are the criterion standard in craniofacial reconstruction for bony defects involving the craniofacial skeleton. The authors have previously demonstrated that graft microarchitecture is the major determinant of volume maintenance for both inlay and onlay bone grafts following transplantation. This study performs a head-to-head quantitative analysis of volume maintenance between inlay and onlay bone grafts in the craniofacial skeleton using a rabbit model to comparatively determine their resorptive kinetics over time.

Methods

Fifty rabbits were divided randomly into six experimental groups: 3-week inlay, 3-week onlay, 8-week inlay, 8-week onlay, 16-week inlay, and 16-week onlay. Cortical bone from the lateral mandible and both cortical and cancellous bone from the ilium were harvested from each animal and placed either in or on the cranium. All bone grafts underwent micro–computed tomographic analysis at 3, 8, and 16 weeks.

Results

All bone graft types in the inlay position increased their volume over time, with the greatest increase in endochondral cancellous bone. All bone graft types in the onlay position decreased their volume over time, with the greatest decrease in endochondral cancellous bone. Inlay bone grafts demonstrated increased volume compared with onlay bone grafts of identical embryologic origin and microarchitecture at all time points (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Inlay bone grafts, irrespective of their embryologic origin, consistently display less resorption over time compared with onlay bone grafts in the craniofacial skeleton. Both inlay and onlay bone grafts are driven by the local mechanical environment to recapitulate the recipient bed.

Nonvascularized autologous bone grafts represent a powerful tool available to the craniofacial surgeon for restoration of bony defects involving the craniofacial skeleton. Indications range from the treatment of traumatic injuries and congenital anomalies to oncologic deformities following extirpation of head and neck tumors.1 Despite their widespread use as the criterion standard in craniofacial reconstruction, the selection of the most appropriate bone graft is often based on anecdotal evidence or the comfort level of the clinician with the technical aspects related to bone graft harvest. The primary goal of any bone grafting procedure is to achieve a long-lasting result by optimizing the survival of the grafted material. The clinical reality, however, is that bone graft resorption and remodeling often eclipse good early surgical outcomes.2 As the overlying soft tissues exert their functional forces, such as stress secondary to recoil or strain caused by muscular tone, volume maintenance of the bone graft is directly influenced, and the likelihood of achieving a predictable result declines significantly over time. This process can be partially avoided through the intelligent, knowledgeable, and informed use of bone grafts in the craniofacial skeleton, and with a better understanding of the underlying scientific principles guiding bone graft dynamics.

Early investigations focused primarily on embryologic origin as the major determinant of volume maintenance in bone grafts, postulating a predetermined survival advantage of membranous bone over endochondral bone.3–14 Indeed, before these experimental studies, direct clinical observation supported less resorption of membranous bone compared with endochondral bone for onlay grafting techniques in the craniofacial skeleton.15 Despite the reproducibility of these claims for full-thickness bone grafts, the structural composition of the grafted material, irrespective of its embryologic origin, was not recognized as a potential confounding variable and a possible alternative explanation for the perceived superiority of membranous bone.16 Unlike endochondral bone, the fundamental biology of membranous bone mandates that a larger proportion of the overall bone volume is composed of cortical bone separated by a sparse intervening cancellous layer. The cortical component lends itself to a more dense and compact osseous framework compared with the cancellous component, imparting greater structural integrity to the graft as a whole.2 These differences in microarchitecture between bone grafts, determined by the relative contributions of their pure cortical and pure cancellous components, were later confirmed by our laboratory to more accurately reflect bone graft behavior and serve as a better predictor of bone graft survival.16,17

The purpose of this study was to expand on our previous work by performing a head-to-head quantitative analysis of volume maintenance between inlay and onlay bone grafts in the craniofacial skeleton using a rabbit model. Our hypothesis is twofold: (1) bone grafts placed in the inlay position maintain their volume better over time compared with those placed in the onlay position; and (2) the improved volume maintenance of bone grafts in the inlay position is the result of the interaction between the local mechanical environment and the microarchitecture of the bone graft (i.e., cortical bone versus cancellous bone). Moreover, an overarching goal of this study was to develop a better understanding of inlay and onlay grafting techniques and to further define the factors known to affect bone graft dynamics, to aid the clinician in the selection of the most appropriate bone graft for a given position and to ensure durability and predictability based on sound biological mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Design

Fifty adult New Zealand white rabbits (Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Haslett, Mich.) were divided randomly into six experimental groups: 3-week inlay (n = 8), 3-week onlay (n = 8), 8-week inlay (n = 9), 8-week onlay (n = 8), 16-week inlay (n = 8), and 16-week onlay (n = 9). Three identical bone grafts were harvested from each animal, including cortical bone of membranous origin from the lateral mandible and both cortical and cancellous bone of endochondral origin from the ilium. All bone grafts were placed either in or on the cranium of the animal according to the experimental group to which it belonged.

Operative Technique

The rabbit’s lateral mandible was accessed through a submandibular approach by making a 3-cm incision over the inferior border of the mandible and then elevating a subperiosteal flap to the level of the sigmoid notch. Next, a uniform cylindrical piece of cortical bone was harvested using a trephine burr attached to an oscillating saw with a 6-mm internal diameter (Aesculap, Inc., Center Valley, Pa.). It is important to note that no cancellous bone was obtained from the lateral mandible because of its relative paucity in membranous grafts. The rabbit was then placed in the prone position, and a gentle arcing 4-cm incision was made over the iliac crest. Subperiosteal sharp dissection was performed, exposing the body of the ilium from the wing to the acetabulum. A uniform cylindrical piece of composite corticocancellous bone was harvested from the proximal ilium just anterior to the acetabulum using the same 6-mm trephine burr. This endochondral graft was easily separated into its individual cortical and cancellous components using a scalpel.

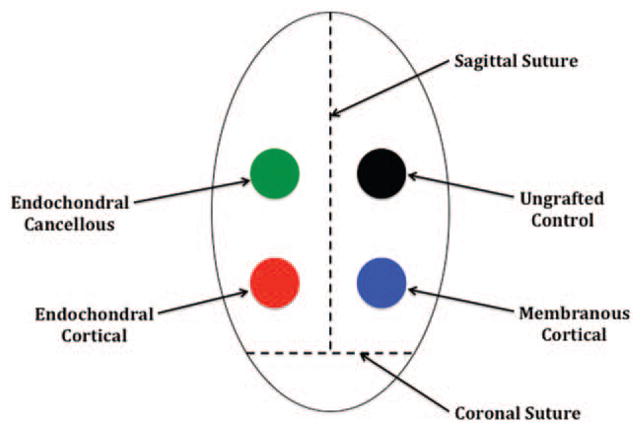

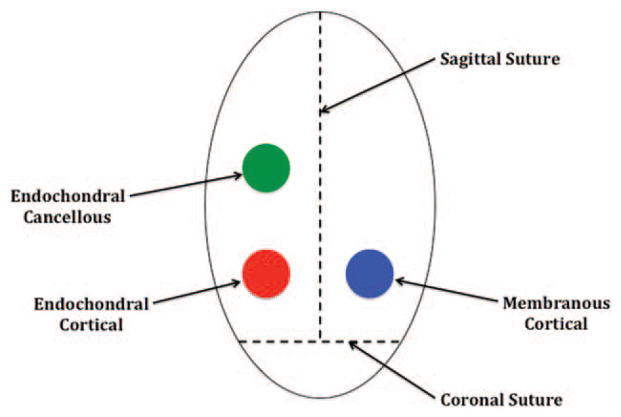

Before transplantation, all bone grafts were measured in triplicate using microcalipers to record both height and diameter values, which were then averaged to assign an initial volume to each bone graft type. A 4-cm sagittal incision was made in the rabbit’s scalp, and bilateral pericranial flaps were elevated. For the inlay group, four holes were drilled into the cranium of each rabbit posterior to the coronal suture using the same 6-mm trephine burr, with additional care being taken not to injure the underlying dura.18 Each bone graft type (i.e., membranous cortical, endochondral cortical, and endochondral cancellous) was then placed into one of the cranial defects, leaving the fourth hole empty as an ungrafted control (Fig. 1). Similarly, for the onlay group each, bone graft type was placed onto the rabbit’s cranium posterior to the coronal suture in preselected areas (Fig. 2). Graft locations for both groups were rotated in a clockwise fashion for each subsequent animal, to reduce any positional biases. All bone grafts were completely covered with pericranial flaps and no other fixation method was used.

Fig. 1.

Inlay placement of bone grafts. All grafts were positioned posterior to the coronal suture and on either side of the sagittal suture.

Fig. 2.

Onlay placement of bone grafts. All grafts were positioned posterior to the coronal suture and on either side of the sagittal suture.

Animals were euthanized according to institutional standards at 3 weeks (n = 8 for inlay, n = 8 for onlay), 8 weeks (n = 9 for inlay, n = 8 for onlay), and 16 weeks (n = 8 for inlay, n = 9 for onlay). All bone grafts were collected as a rectangular block of tissue including a 0.5-cm rim of the surrounding normal cranium, and immediately underwent micro–computed tomographic scanning. The specimens were handled with absolute care to avoid disturbing the graft/cranium interface, and were subsequently stored in 70% ethanol.

Micro–Computed Tomography

Three-dimensional micro–computed tomography is a validated instrument for precisely measuring changes in the microarchitecture of bone grafts, and has been previously used to characterize the structural composition of both membranous and endochondral bone in our laboratory.19–23 Because the scanning is performed in a nondestructive manner, the graft/cranium interface remains undisturbed and the bone specimen as a whole can be subjected to further analytic testing. Proprietary software was used to calculate the final volume of the bone graft, which was then divided by its initial volume to determine its relative bone volume.

Statistical Analysis

Using SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C.), a repeated-measures analysis of variance was first performed to verify the independence of each bone graft type from the time the animals were euthanized. Volume comparisons were then made separately for each bone graft type at all time points using a paired t test with the Bonferroni correction. Finally, repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to explore differences in volume maintenance between the bone graft types within the same position and then between positions. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Inlay Bone Grafts Increase in Volume

All bone graft types in the inlay position (membranous cortical, endochondral cortical, and endochondral cancellous) increased their volume over time, or they all deposited bone (Table 1). Membranous and endochondral cortical bone demonstrated a significant increase in volume compared with baseline of 77.4, 126.4, and 138.2 percent and 39.8, 67.3, and 44.1 percent at 3, 8, and 16 weeks, respectively. However, for both groups, no significant difference was found between time points. Endochondral cancellous bone demonstrated the greatest increase in volume compared with baseline of 247.2, 223.4, and 305.9 percent at 3, 8, and 16 weeks, respectively. A significant difference was also noted between time points, except between weeks 3 and 8. By 16 weeks, new bone formation in the endochondral cancellous group showed a massive and statistically significant increase in comparison with both the endochondral and membranous cortical groups (p < 0.05). Finally, the ungrafted control demonstrated bone deposition around the periphery beginning at 3 weeks and maintained a central defect through 16 weeks.

Table 1.

Volume of Inlay Bone Grafts at 3, 8, and 16 Weeks*

| Time (wk) | Percentage of Initial Volume

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MC | EC | ECa | |

| 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 177.4±46.7 | 139.8±28.7 | 347.2±43.1 |

| 8 | 226.4±51.3 | 167.3±29.1 | 323.4±51.7 |

| 16 | 238.2±48.2 | 144.1±29.3 | 405.9±44.2 |

MC, membranous cortical; EC, endochondral cortical; ECa, endochondral cancellous.

Values are mean ± SD (3 wk, n = 8; 8 wk, n = 9; 16 wk, n = 8).

Onlay Bone Grafts Decrease in Volume

All bone graft types in the onlay position (membranous cortical, endochondral cortical, and endochondral cancellous) decreased their volume over time, or they all resorbed bone (Table 2). Membranous and endochondral cortical bone demonstrated a significant decrease in volume compared with baseline, retaining 70.3, 58.3, and 56.0 percent and 62.5, 63.0, and 52.1 percent at 3, 8, and 16 weeks, respectively, of their initial volume. Endochondral cancellous bone demonstrated the greatest decrease in volume compared with baseline, retaining 3.4, 8.1, and 2.1 percent at 3, 8, and 16 weeks, respectively, of its initial volume. Importantly, endochondral cancellous bone also displayed a significantly greater amount of bone resorption than either endochondral or membranous cortical bone at all time points (p < 0.05). However, no significant difference in the amount of bone resorption between endochondral and membranous cortical bone was noted at any of the time points.

Table 2.

Volume of Onlay Bone Grafts at 3, 8, and 16 Weeks*

| Time (wk) | Percentage of Initial Volume (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MC | EC | ECa | |

| 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 70.3±7.5 | 62.5±8.7 | 3.4±2.3 |

| 8 | 58.3±4.9 | 63.0±9.0 | 8.1±21.9 |

| 16 | 56.0±16.8 | 52.1±17.6 | 2.1±4.1 |

MC, membranous cortical; EC, endochondral cortical; ECa, endochondral cancellous.

Values are mean ± SD (3 wk, n = 8; 8 wk, n = 8; 16 wk, n = 9).

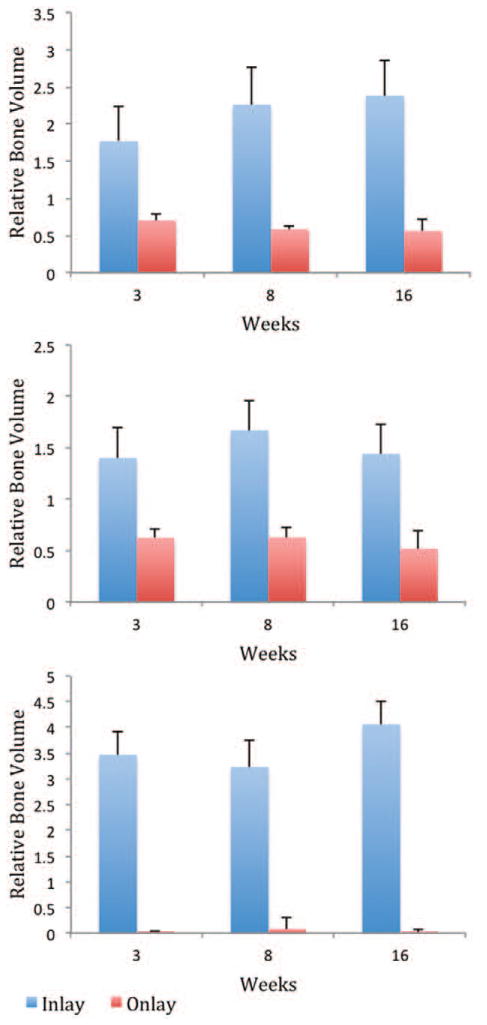

Volume Comparison between Inlay and Onlay Bone Grafts

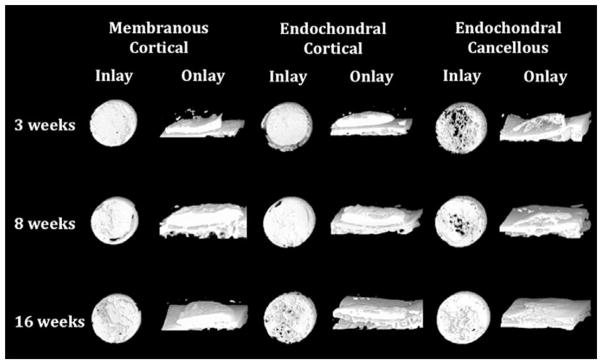

A statistically significant increase in volume was found in inlay bone grafts compared with onlay bone grafts of identical embryologic origin and microarchitecture at all time points (p < 0.05), with the greatest difference observed in the endochondral cancellous group. Inlay bone grafts demonstrated actual bone growth and expansion, whereas onlay bone grafts consistently displayed bone resorption (Fig. 3). Inlay bone grafts had massive increases in relative bone volume compared with onlay bone grafts for membranous cortical bone (2.5-, 3.9-, and 4.3-fold), endochondral cortical bone (2.2-, 2.7-, and 2.8-fold), and endochondral cancellous bone (102.1-, 39.9-, and 193.3-fold) at 3, 8, and 16 weeks, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional micro–computed tomographic representations of inlay and onlay bone grafts at 3, 8, and 16 weeks. All inlay bone grafts, irrespective of embryologic origin, demonstrated actual bone growth and expansion, whereas all onlay bone grafts were consistently resorbed (original magnification, × 40).

Fig. 4.

Volume comparison of membranous cortical (above), endochondral cortical (center), and endochondral cancellous (below) bone grafts in the inlay and onlay positions.

Observed Microarchitectural Changes

Both membranous and endochondral cortical bone grafts in the inlay position became more porous over time, whereas endochondral cancellous bone became less porous, suggesting that the functional forces of the local mechanical environment act to converge all bone grafts toward one phenotype in an effort to recapitulate the recipient bed. Similar findings were demonstrated in onlay bone grafts, with membranous and endochondral cortical bone becoming more porous over time and endochondral cancellous bone becoming less porous but to a much lesser degree. Moreover, pseudocorticalization was noted along the dural and pericranial surfaces of the endochondral cancellous bone.

DISCUSSION

The first theory describing embryologic origin as the key dominant factor in bone graft dynamics originated in direct clinical observation. Peer15 noted that in his patients with disparate craniofacial defects, membranous bone resorbed less over time than endochondral bone when placed in the onlay position. This led to the postulate of membranous bone having a predetermined survival advantage over endochondral bone, which was further supported by the experimental studies of Smith and Abramson12 and Zins and Whitaker.11 Both groups demonstrated improved survival of cranial bone compared with iliac bone using onlay grafting techniques in a rabbit model. More recently, Hardesty and Marsh6 and others24 suggested that membranous bone persists and endochondral bone collapses because of differences in thickness between their cortical and cancellous plates. In other words, graft microarchitecture accounts more for the observed differences in volume maintenance than does embryologic origin. Ozaki and Buchman16 explored this concept further by separating membranous and endochondral bone grafts into their pure cortical and pure cancellous components. Using micro–computed tomography, the authors demonstrated some degree of resorption in all bone graft types, although cortical bone, irrespective of its embryologic origin, was by far the superior onlay grafting material. This experimental study confirmed that graft microarchitecture more accurately reflects bone graft behavior and serves as a better predictor of bone graft survival for onlay grafting techniques.

Inlay bone grafts were then investigated to determine the influence of graft microarchitecture on their volume maintenance properties. In a rabbit model, Rosenthal and Buchman17 demonstrated no resorption but actual bone growth and expansion in the inlay position. Quantitative data further indicated that cancellous bone grew to a much greater degree than cortical bone, irrespective of its embryologic origin. More importantly, the local mechanical environment in which the bone was transplanted seemed to converge all grafts toward one phenotype in an effort to recapitulate the recipient bed. These results, similar to the findings for onlay bone grafts, provide support for graft microarchitecture as the major determinant of volume maintenance in inlay bone grafts.

In the current study, we expand on the previous works of Ozaki and Buchman16 and Rosenthal and Buchman17 by directly comparing inlay and onlay bone grafts in the craniofacial skeleton to quantitatively analyze differences in their volume maintenance properties. We found that for bone grafts of identical embryologic origin and microarchitecture, inlay bone grafts maintained volume better over time compared with onlay bone grafts. Our findings are similar to those of LaTrenta et al.,8 who also reported improved volume maintenance of inlay over onlay bone grafts in a dog model. A major difference between their study and ours, however, is that they used composite grafts, whereas we separated our grafts into their pure cortical and pure cancellous components. Nonetheless, both studies support inlay grafting as the preferred technique in the craniofacial skeleton for preserving bone volume over time, but the source of this influence is still unknown.25 Among the many factors shaping the fate of nonvascularized autologous bone grafts, we believe the chief predictors of bone graft survival are the local mechanical environment in which the bone is transplanted and the extent to which that bone is revascularized. By distilling these factors into a function of two parameters, namely, the local mechanical environment and the extent of revascularization, a logical and consistent theory of bone graft behavior may be formulated, and the problem of volume maintenance can be reasonably approached.

Approximately two decades after Duterloo and Enlow26 and Bang and Enlow27 first introduced the concept of the resorptive field in the late 1960s, Whitaker7 described the concept of biological boundaries, spotlighting the importance of the inherently restrictive overlying soft-tissue envelope. Based on his clinical observations, the human body possesses a genetically predetermined shape that is inclined to remain constant. He further emphasized that bone grafts maintain their volume significantly better in the inlay position than in the onlay position because less change is provoked in the overlying soft tissues. Not recognizing the heterogenous microarchitectural differences between membranous and endochondral bone, the author was led to the erroneous conclusion of embryologic origin being the major determinant of volume maintenance in bone grafts. Although our conclusions may differ, our findings in this study are consistent with Whitaker’s empiric observations and his derivative concept of the biological boundary. Both inlay and onlay bone grafts attempted to reestablish the same anatomical limits. In other words, incorporation of the bone graft was biased by the local mechanical environment and resisted extension beyond the full thickness of the rabbit’s cranium.

The observed differences in volume maintenance between inlay and onlay bone grafts can be partially explained by the interaction between the local mechanical environment and the grafted material.2,28 Onlay bone grafts stretch and deform the overlying soft-tissue envelope, generating recoil forces that act directly on the graft. Goldstein et al.29 demonstrated improved volume maintenance of bone grafts placed under preexpanded soft-tissue envelopes compared with unexpanded controls. Conversely, inlay bone grafts are selectively shielded from these harmful recoil forces and are the beneficiaries of the same physical stresses received by the surrounding normal cranium. The presence of these functional forces create a favorable biomechanical matrix in which the phenotype of the grafted material is driven toward that of the recipient bed, rather than maintaining its native structural fabric. Cortical bone placed in the inlay position becomes more porous over time, whereas cancellous bone becomes less porous. Similar findings are observed in the onlay position but to a much lesser degree. Pseudocorticalization is also noted along the dural and pericranial surfaces of the cancellous bone, further supporting our findings of a congruence in form of the remodeled bone to that of the surrounding normal cranium.

Finally, graft microarchitecture has profound implications on the extent of revascularization and the rate at which it takes place. Previous studies have demonstrated that cancellous bone revascularizes faster than cortical bone, and to a much greater extent.5,10,24,30,31 Therefore, when cancellous bone is placed in the onlay position, the combination of recoil forces and efficient revascularization leads to intense resorption. Cortical bone is subject to the same recoil forces when placed in the onlay position, but less osteoclastic activity ensues because of slow and incomplete revascularization. The net result is better volume maintenance with cortical bone compared with cancellous bone in the onlay position, irrespective of its embryologic origin. Because of increased bone-to-bone contact, inlay bone grafts have a greater potential for revascularization, osteogenesis, osteoconduction, and osteoinduction.2 The absence of recoil forces, the presence of reinforcing functional stresses, and the robust osteogenic activity found in inlay bone grafts are the central factors responsible for their superior volume maintenance over onlay bone grafts in the craniofacial skeleton.

CONCLUSIONS

Although embryologic origin was once considered the major determinant of volume maintenance in bone grafts, a shift in the paradigm of bone graft dynamics has occurred over the past few decades, with graft microarchitecture now being the better predictor of bone graft survival. Interaction with the local mechanical environment and the extent of revascularization has established guiding fundamental principles in bone graft physiology. These principles have their origins in Wolff’s law and act to unify apparent inconsistencies in previous research. Quantitative data from this study support the concepts of biological boundaries and resorptive fields originally espoused by Whitaker and Enlow, and provide credence for the superiority of inlay over onlay grafting techniques for volume maintenance in the craniofacial skeleton.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by THE PLASTIC SURGERY FOUNDATION.

This project was supported by grants from the Plastic Surgery Foundation and from the University of Michigan Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Center (NIH P60-AR20557). The authors thank the Center for Statistical Consultation and Research at the University of Michigan for help with the data analyses.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

References

- 1.Habal MB. Bone grafting in craniofacial surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 1994;21:349–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oppenheimer AJ, Tong L, Buchman SR. Craniofacial bone grafting: Wolff’s law revisited. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2008;1:49–61. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1098963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donovan MG, Dickerson NC, Hellstein JW, Hanson LJ. Autologous calvarial and iliac onlay bone grafts in miniature swine. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:898–903. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips JH, Rahn BA. Fixation effects on membranous and endochondral onlay bone graft revascularization and bone deposition. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85:891–897. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199006000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin KY, Bartlett SP, Yaremchuk MJ, Fallon M, Grossman RF, Whitaker LA. The effect of rigid fixation on the survival of onlay bone grafts: An experimental study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:449–456. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199009000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardesty RA, Marsh JL. Craniofacial onlay bone grafting: A prospective evaluation of graft morphology, orientation, and embryonic origin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85:5–14. discussion 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitaker LA. Biological boundaries: A concept in facial skeletal restructuring. Clin Plast Surg. 1989;16:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaTrenta GS, McCarthy JG, Breitbart AS, May M, Sissons HA. The role of rigid skeletal fixation in bone-graft augmentation of the craniofacial skeleton. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:578–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salyer KE, Taylor DP. Bone grafts in craniofacial surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14:27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zins JE, Kusiak JF, Whitaker LA, Enlow DH. The influence of the recipient site on bone grafts to the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:371–381. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198403000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zins JE, Whitaker LA. Membranous versus endochondral bone: Implications for craniofacial reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;72:778–785. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198312000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith JD, Abramson M. Membranous vs endochondrial bone autografts. Arch Otolaryngol. 1974;99:203–205. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1974.00780030211011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enneking WF, Morris JL. Human autologous cortical bone transplants. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1972;87:28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson N, Casson JA. Experimental onlay bone grafts to the jaws: A preliminary study in dogs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1970;46:341–349. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197010000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peer LA. Fate of autogenous human bone grafts. Br J Plast Surg. 1951;3:233–243. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(50)80038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozaki W, Buchman SR. Volume maintenance of onlay bone grafts in the craniofacial skeleton: Micro-architecture versus embryologic origin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:291–299. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199808000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenthal AH, Buchman SR. Volume maintenance of inlay bone grafts in the craniofacial skeleton. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:802–811. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000069713.62687.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopper RA, Zhang JR, Fourasier VL, et al. Effect of isolation of periosteum and dura on the healing of rabbit calvarial inlay bone grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:454–462. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200102000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozaki W, Buchman SR, Goldstein SA, Fyhrie DP. A comparative analysis of the microarchitecture of cortical membranous and cortical endochondral onlay bone grafts in the craniofacial skeleton. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:139–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchman SR, Sherick DG, Goulet RW, Goldstein SA. Use of microcomputed tomography scanning as a new technique for the evaluation of membranous bone. J Craniofac Surg. 1998;9:48–54. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199801000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein SA, Matthews LS, Kuhn JL, Hollister SJ. Trabecular bone remodeling: An experimental model. J Biomech. 1991;24(Suppl 1):135–150. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90384-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feldkamp LA, Goldstein SA, Parfitt AM, Jesion G, Kleerekoper M. The direct examination of three-dimensional bone architecture in vitro by computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 1989;4:3–11. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650040103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Layton MW, Goldstein SA, Goulet RW, Feldkamp LA, Kubinski DJ, Bole GG. Examination of subchondral bone architecture in experimental osteoarthritis by microscopic computed axial tomography. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1400–1405. doi: 10.1002/art.1780311109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen NT, Glowacki J, Bucky LP, Hong HZ, Kim WK, Yaremchuk MJ. The roles of revascularization and resorption on endurance of craniofacial onlay bone grafts in the rabbit. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:714–722. discussion 723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oppenheimer AJ, Mesa J, Buchman SR. Current and emerging basic science concepts in bone biology: Implications in craniofacial surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:30–36. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318240c6d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duterloo HS, Enlow DH. A comparative study of cranial growth in Homo and Macaca. Am J Anat. 1970;127:357–368. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001270403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bang S, Enlow DH. Postnatal growth of the rabbit mandible. Arch Oral Biol. 1967;12:993–998. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(67)90094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang N, Butler JP, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science. 1993;260:1124–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.7684161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein J, Mase C, Newman MH. Fixed membranous bone graft survival after recipient bed alteration. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91:589–596. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinholt EM, Solheim E, Talsnes O, Larsen TB, Bang G, Kirkeby OJ. Revascularization of calvarial, mandibular, tibial, and iliac bone grafts in rats. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;33:193–197. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199408000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lukash FN, Zingaro EA, Salig J. The survival of free nonvascularized bone grafts in irradiated areas by wrapping in muscle flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74:783–788. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198412000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]