Abstract

Background

Cast immobilisation after successful closed reduction is a standard treatment for displaced extra-articular fractures of lower end radius. The position of the wrist during immobilisation is controversial. Immobilisation in dorsiflexion prevents redisplacement after closed reduction. Our aim is to determine the effectiveness of immobilization of wrist in dorsiflexion in such cases and evaluate anatomical and functional outcome.

Materials and methods

Study included 54 patients, above 19 years of age with closed extra-articular fractures of lower end radius treated conservatively with below elbow cast application. The wrist was maintained in 15° of dorsiflexion during plaster immobilisation. At 24 weeks, functional results were evaluated with subjective symptoms and objective signs, as per modified Demerit Point Score System. Anatomical result was evaluated based on the scheme devised by Lidstrom (1959) and modified by Sarmiento et al. (1980).

Results

76% patients had Excellent to Good subjective symptoms. Out of 42 patients that had residual dorsal angulation of less than 10°, 37 had excellent to good functional outcome. 39 of the 43 patients who had loss of radial length less than 6 mm had excellent to good functional outcome. 40 out of 49 patients having loss of radial angulation less than 9° showed excellent to good functional outcome. Functional result was directly proportional to anatomical outcome.

Conclusion

Cast immobilization of extra articular fractures of lower end radius with wrist in dorsiflexion prevents re-displacement of the fragments resulting in satisfactory anatomical & functional outcome.

Keywords: Colles fracture, Dorsiflexion, Distal radius fractures, Extra articular fractures radius, Cast immobilisation

1. Introduction

Historically, closed reduction and cast immobilization has been the mainstay of treatment in Colles fracture1 and still continues to do so in selected cases.2 Although above elbow cast is preferred, a forearm cast is sufficient.3–5 Plaster immobilization in slight dorsiflexion of wrist has been found to give better radiological and functional results in such cases.6,7 The present study was undertaken with an aim to determine the effectiveness of immobilization of wrist in dorsiflexion in maintaining the position of displaced extra articular distal radius fractures (Colles type) after successful closed reduction with the objective to assess the functional outcomes associated with it.

2. Materials & methods

The study was carried out from September 2007 to October 2008, after obtaining clearance from the Institutional Ethics Committee. Informed consent was taken from each patient prior to inclusion in the study.

103 patients with extra-articular fractures, Colles type of distal radius fracture, who underwent conservative treatment with wrist immobilised in dorsiflexion formed the material. Out of 103 patients, 49 patients were excluded from the study due to either drop out or incomplete data. This left with 54 patients for final evaluation. The injury was classified according to Fernandez classification.8 Type 1 fractures (Fernandez Bending fractures with posterior displacement), in either sex, of less than 10 days duration were included in the study. Fractures with extension into the joint, associated fractures in the affected limb, gross communition and open fractures were excluded from the study.

There were 23 male and 31 female patients. The right hand was affected in 32 patients while patients aged 35–55 years showed highest incidence. All the injuries followed low energy trauma of fall on outstretched hand. The limb was immobilised initially with a dorsal POP slab for 4–5 days to reduce swelling with elevation of the arm and active finger movements. Closed reduction was done under general anaesthesia and C-arm control. After satisfactory reduction, a below elbow cast was applied still maintaining the reduction. As the plaster was hardening, the assistant slowly brought the wrist to 15° of dorsiflexion and slight ulnar deviation while maintaining the traction. The Surgeon continued the palmar flexion pressure at the distal fragment to maintain its palmar tilt all the time. This also ensured dorsiflexion at the wrist and not at the fracture site. The plaster was well moulded over the wrist (Fig 1).

Fig. 1.

Surgeon stabilising the fracture while the assistant produces dorsiflexion and ulnar deviation at wrist joint.

Rehabilitation was started soon after the patient recovered from anaesthesia with active movements of the fingers. After three days of rest, active movements at the shoulder and elbow started.

The first follow up was done at 10th day of manipulation to rule out any redisplacement with X-ray. The plaster was removed at 4 weeks and active wrist movements including supination and pronation was advised and instructed with warm saline bath in between. Final follow up was done at 24 weeks for Subjective symptoms and Objective signs, all of which were subjected to a Modified Demerit Point Score System to evaluate functional results. The end result was marked as Excellent (0–2 points), Good (3–8 points), Fair (9–20) and Poor (21 or more points).9

The anatomical result was evaluated based on the scheme devised by Lidstrom (1959) and modified by Sarmiento et al. (1980). Values for the dorsal angle, the radial length and the radial angle were obtained. The radial tilt was measured as the angle between the distal radial articular surface on AP view to a line perpendicular to the long axis of the radius (normal = 22–23° range 13–30°). On lateral view the angle created between the articular surface of the distal radius and a line perpendicular to the long axis of the radius denoted the palmar tilt (normal = 11–12° range – 0–28°). Radial length was represented by the distance between two perpendiculars to the long axis of radius, one at the tip of the radial styloid and the other at the distal articular surface of the ulnar head. Anatomical grades obtained by addition of the three scores for each result was classified as Excellent (0 score), Good (1–3 score), Fair (4–6 score) and Poor (7–12 score).4

A goniometer was used for the measurement of range of movement of wrist joint of the healthy and injured hand at 6 months after treatment. Measurement of grip strength was done by inflating a rolled sphygmomanometer cuff to 20 mm of Hg. Thereafter, the patient was asked to squeeze and the pressure achieved was recorded. Readings were taken for both the injured and uninjured hands for comparison.

3. Results

3.1. Subjective evaluation

Subjective evaluation was done on the basis of pain, restriction of movements and disability. At the final follow-up of 6 months, 76% of the patients had Excellent to Good subjective symptoms. Rest 24% cases had slight symptoms with Fair outcome. Weakness of the grip strength was the most frequent symptom observed in 28 (52%) out of the total patient of 54 showing this symptom.

3.2. Objective evaluation

-

a)

Residual deformity: Out of the 54 patients, 33 had some form of deformity at the end of 6 months. The most common deformity observed was prominence of ulnar styloid process (Radial shortening) followed by dorsal deformity. 26 (48.15%) patients had residual radial shortening while 19 (35%) patients had residual dorsal tilt.

-

b)

Pain in distal radio-ulnar joint: Pain in distal radio ulnar joint was present in 26 patients (48%).

-

c)

Loss of mobility: The most common movement to be lost was loss of radial deviation (44%), followed by loss of circumduction (31.48%).

-

d)

Grip strength: At 6 months it was found that only 28 (52%) cases had diminished grip strength. It was found that impaired grip strength had a strong correlation with overall functional outcome. 25% of the patients with excellent outcome had impaired grip strength while 70% of the patients with good or fair outcome had impaired grip strength at 6 months.

-

e)

Complications: No complication was seen in any of the patient in our study group like median nerve compression, shoulder–hand syndrome, Sudeck's osteodystrophy etc. As the study period of each case was only 6 months, no case was followed up to study the osteoarthritic changes.

3.3. Functional end results

76% of our patients had excellent to good result and 24% had fair result; there was no poor outcome.(Table 1)

Table 1.

Functional end result assessed on the basis of demerit point score system at 6 months.

| Demerit point score system | No. of patient | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0–2 (Excellent) | 16 | 29.63 |

| 3–8 (Good) | 25 | 46.30 |

| 9–20 (Fair) | 13 | 24.07 |

| >20 (Poor) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 54 | 100 |

3.4. Anatomical results

Out of 42 patients that had residual dorsal angulation of less than 10°, 37 (88.10%) had excellent or good functional outcome. It was also seen that 8 (66.67%) out of the 12 patients having residual deformity of greater than 10° had adverse outcome. 39 of the 43patients (90.70%) who had loss of radial length less than 6 mm had excellent to good functional outcome (Figs. 2–4) (Tables 2 and 3). Functional outcome was found to be adverse in 9 out of the 11 (81.82%) patients having loss of radial length more than 7 mm. 40 out of 49 (81.62%) patients having loss of radial angulation less than 9° showed excellent to good functional outcome (Fig 5). On the other hand, 4 out of the 5 patients (80%) having loss of radial angle more than 14° had fair functional outcome.

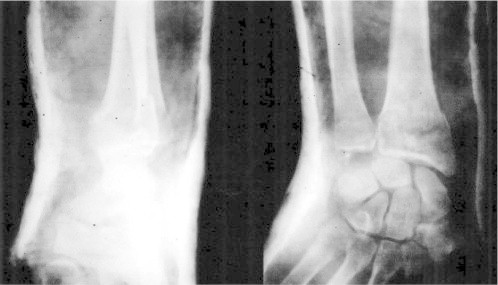

Fig. 2.

Pre-operative X-ray of Colles' fracture.

Fig. 3.

Post-reduction X-ray with wrist in dorsiflexion and ulnar deviation.

Fig. 4.

X-ray at final follow-up at 24 weeks.

Table 2.

Anatomical outcome on basis of scheme by Lidstrom (modified by Sarmiento) at 6 months.

| Residual deformity | Excellent | Good | Fair | Poor | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorsal angle (degree) | Neutral | 13 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 23 |

| 1–10 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 0 | 19 | |

| 11–14 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 10 | |

| >15 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Total | 16 | 25 | 13 | 0 | 54 | |

| Loss of radial length (mm) | <3 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| 3–6 | 8 | 16 | 4 | 0 | 28 | |

| 7–11 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 11 | |

| ≥12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 16 | 25 | 13 | 0 | 54 | |

| Loss of radial angle (degree) | 0–4 | 15 | 22 | 5 | 0 | 42 |

| 5–9 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| 10–14 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| ≥15 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 16 | 25 | 13 | 0 | 54 | |

Table 3.

Anatomical outcome on basis of scheme by Lidstrom (modified by Sarmiento) at 6 months.

| Anatomical outcome | No. of patient | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (Excellent) | 7 | 12.96 |

| 1–3 (Good) | 36 | 66.67 |

| 4–6 (Fair) | 10 | 18.52 |

| 7–12 (Poor) | 1 | 1.85 |

| Total | 54 | 100 |

Fig. 5.

Clinical outcome at 24 weeks.

3.5. Comparison of Anatomical and Functional outcome

Functional result was directly proportional to Anatomical outcome (Table 4). All the 43 patients having excellent to good anatomical result had excellent to good functional outcome.

Table 4.

Comparison of anatomical and functional outcome.

| Anatomical | Functional result |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | Good | Fair | Poor | Total | |

| Excellent | 6 (85.71%) | 1 (14.29%) | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Good | 10 (27.78%) | 23 (63.89%) | 3 (8.33%) | 0 | 36 |

| Fair | 0 | 1 (10%) | 9 (90%) | 0 | 10 |

| Poor | 0 | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 16 | 26 | 12 | 0 | 54 |

4. Discussion

Closed reduction followed by cast immobilization is regarded as a standard technique in the treatment of distal radius fractures. Although there is general agreement that the anatomical outcome of plaster cast immobilization is determined by the stability of the fracture, the optimal means of immobilizing distal radius fractures remains a topic of debate. While a number of current studies recommend casting of distal radius fractures with the forearm in neutral rotation or slight pronation combined with mild flexion and ulnar deviation of the wrist, few others recommend alternate treatment modalities which include immobilization in neutral and dorsiflexion.10,11 Even studies done as early as 1910 & 1932 also maintained that dorsiflexion and ulnar deviation to some extent resulted in satisfactory outcome.8,12

Fractures immobilized with the wrist in dorsiflexion showed the lowest incidence of redisplacement, especially of dorsal tilt, and had the best early functional results. In palmar flexion the dorsal carpal ligament is taut, but cannot stabilize the fracture because of its lack of an attachment to distal carpal row. The deforming forces and the potential displacement of the fracture are parallel, in the same direction. In dorsiflexion, the volar ligaments are taut and tend to pull the fracture fragment anteriorly. The deforming forces act at an angle, which tends to reduce the displacement of the fracture.7 Also the wrist in extension is the optimal position for hand function and rehabilitation of the fingers.6 In this study we compared the functional and radiological results of extra-articular Colles type of distal radius fractures treated conservatively with wrist immobilized in dorsiflexion. We found that individual movements of supination, pronation, ulnar and radial deviation as well as total range of movements are satisfactory when the wrist is immobilized in dorsiflexion, the fact that has equally being concluded by earlier studies.6,7 Further, recovery of grip strength and subjective assessment of pain, disability and limitation of the movements were also encouraging.

Radiological parameters as measured by ulnar variance, palmar tilt and radial tilt were found to be well maintained if the wrist was immobilised in dorsiflexion with a decreased chance of redisplacement.

5. Conclusion

When the extra-articular fractures of the lower end radius are treated conservatively, flexion should be at fracture site to make use of the periosteal hinge but the wrist should be immobilized in position of slight dorsiflexion (extension), so that this optimal functional position of the wrist maintains the reduction during its healing process. This also enhances the rehabilitation of fingers during the treatment.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Beumer A., McQueen M.M. Fractures of the distal radius in low-demand elderly patients: closed reduction of no value in 53 of 60 wrists. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:98–100. doi: 10.1080/00016470310013743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarmiento A., Latta L.L. Colles fractures: functional treatment in supination. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2014;81:197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pool C. Colles fracture. A prospective study of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1973;55:540–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart H.D., Innes A.R., Burke F.D. Functional cast bracing for Colless fracture. A comparison between cast bracing and conventional plaster casts. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66:749–753. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.66B5.6389558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hondoll H.H., Madhok R. Conservative interventions for treating distal radius fractures in adult H. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2003:CD000314. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajan S., Jain S., Ray A., Bhargava P. Radiological and functional outcome in extra-articular fractures of lower end radius treated conservatively with respect to its position of immobilization. Indian J Orthop. 2008;42:201–207. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.40258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta A. The treatment of Colles fracture: immobilisation with the wrist dorsiflexed. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:312–315. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B2.2005163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez D.L., Jupiter J.B. 1st ed. Springer and Verlag; New York: 1996. Fracture of Distal Radius – a Practical Approach to Management; pp. 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarmiento A., Pratt G.W., Berry N.C., Sinclair W.F. Colles fractures: functional bracing in supination. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57-A:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooney W.P. Fractures of the distal radius. In: Cooney W.P., Linscheid R.L., Dobyns J.H., editors. The Wrist: Diagnosis and Operative Treatment. 1st ed. Mosby; St. Louis (MO): 1998. pp. 310–355. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez D.L., Palmer A.K. Green's Operative Hand Surgery. 4th ed. Churchill-Livingstone; New York: 1998. Fractures of the distal radius. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohler L. 3rd ed. Grune and Stratton; New York: 1932. The Treatment of Fractures; pp. 90–96. [Google Scholar]