Abstract

Circulating levels of triacylglycerol (TG) is a recognized risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease, a leading cause of death worldwide. The Institute of Medicine and the American Heart Association both recommend the consumption of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), specifically eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), to reduce serum TG in hyperlipidemic individuals. Additionally, a number of systematic reviews have shown that individuals with any degree of dyslipidemia, elevated serum TG and/or cholesterol, may benefit from a 20-30 % reduction in serum TG after consuming n-3 PUFA derived from marine sources. Given that individuals with serum lipid levels ranging from healthy to borderline dyslipidemic constitute a large portion of the population, the focus of this review was to assess the potential for n-3 PUFA consumption to reduce serum TG in such individuals. A total of 1341 studies were retrieved and 38 clinical intervention studies, assessing 2270 individuals, were identified for inclusion in the current review. In summary, a 9-26 % reduction in circulating TG was demonstrated in studies where ≥ 4 g/day of n-3 PUFA were consumed from either marine or EPA/DHA-enriched food sources, while a 4-51 % reduction was found in studies where 1–5 g/day of EPA and/or DHA was consumed through supplements. Overall, this review summarizes the current evidence with regards to the beneficial effect of n-3 PUFA on circulating TG levels in normolipidemic to borderline hyperlipidemic, otherwise healthy, individuals. Thus demonstrating that n-3 PUFA may play an important role in the maintenance of cardiovascular health and disease prevention.

Keywords: n-3 PUFA, Cardiovascular disease, Normolipidemic, Cholesterol, Triacylglycerol

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading causes of mortality in North America, accounting for 1/3 and 1/6 of all deaths in Canada and the United States, respectively [1, 2]. Elevated levels of circulating triacylglycerol (TG) have been identified as an independent risk factor for developing CVD; evidence from Hokanson et al. indicates that an 88 mg/dL increase in fasting TG levels elevates the risk of developing CVD by 14 % and 37 %, in males and females, respectively [3–8]. Additionally, a large proportion of Canadians and Americans (26 % and 14 %, respectively) have been reported to be either hypertriglyceridemic or hyperlipidemic [2, 9, 10]. Omega 3 (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) have well-established TG lowering effects in hyperlipidemic individuals which may extend to normolipidemic populations [11–19].

The 2002 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on Dietary Reference Intakes for various macronutrients, including fat, states that, “Supplementation with fish oil, which is high in EPA and DHA, reduces triacylglycerol concentrations; low density lipoprotein cholesterol and high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations are either increased or unchanged” [11]. Food and supplement based studies assessing the lipid-lowering effects of n-3 PUFA have utilized a variety of oils comprised of either flaxseed-derived alpha-linolenic acid (18:3 n-3, ALA), algal-derived pure eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5 n-3, EPA) or docosahexaenoic acid (22:6 n-3, DHA), or some combination of these n-3 PUFA through the consumption of fish or fish oils. It is therefore important to determine which forms of n-3 PUFA, or combination of forms, are bioactive in affecting serum TG levels and to detect differences in efficacy among various forms.

Systematic reviews by Wei and Jacobson, Bernstein et al., and Eslick et al. highlight the lipid-lowering capacity of different sources and forms of n-3 PUFA in populations that range from normolipidemic to hyperlipidemic [20–22]. Wei and Jacobson compared the efficacy of DHA to EPA and found that individuals who consumed either DHA or EPA experienced reductions in serum TG of 18.5 % and 32 %, respectively. Individuals also exhibited significantly elevated serum low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) levels by 5 % after DHA consumption, while those consuming EPA had a non-significant reduction in serum LDL-c of 1 % [20]. Additionally, Bernstein et al. concluded that DHA from algal oil plays a role in reducing serum TG while elevating serum LDL-c [21]. The results of a systematic review by Eslick et al. showed that 3.25 g/day of fish oil (1.9 g of EPA and 1.35 g of DHA) reduced serum TG by 14 %, yet cholesterol levels were not altered beyond a clinically insignificant increase in LDL-c [22]. Similar results were obtained in systematic reviews by Balk et al. and Mori et al., both of which assessed studies in which individuals consumed either fish, algal EPA or algal DHA oils [23, 24]. While results from the previously identified systematic reviews indicate that DHA contributes to slight increases in LDL-c and EPA contributes to minor reductions in LDL-c, both n-3 PUFA were established to be efficacious in significantly lowering serum TG levels.

The previously discussed meta-analyses and systematic reviews concur with the observation that EPA and DHA, derived from fish or algal oils, can reduce serum lipids, most notably TG. However, these analyses primarily focused on hyperlipidemic individuals, a population likely to achieve the most drastic reduction in TG levels upon n-3 PUFA consumption, and may conceal a lack of response in normolipidemic subjects, whom with they were pooled [18]. The purpose of the current review is to provide new knowledge with regards to our understanding of the effect of dietary and supplemental n-3 PUFA intake on blood lipid profiles in healthy individuals, using the 2002 IOM report as a reference point. A focus will be placed on the TG-lowering ability of n-3 PUFA in normal to borderline hyperlipidemic populations as defined by AHA guidelines.

Methods

Search strategy

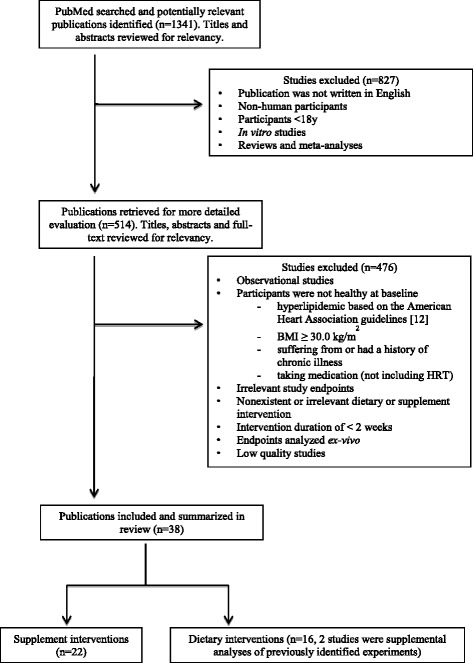

Using the PubMed search engine, clinical trials and observational studies relating to the effects of n-3 PUFA on serum biomarkers of CVD were collected. Search terms (described below) were used to gather studies published from January 1, 2000 – October 1, 2013 as they were not captured within the reference point of the 2002 IOM report. Search terms relating to cholesterol, C-reactive protein (CRP) and chronic illnesses were used to capture the entirety of literature analyzing blood lipids as such studies would likely have included TG measurements (Fig. 1 summarizes the search strategy).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study selection and exclusion methodology

Search terms:

n-3 OR omega 3 OR EPA OR eicosapentaenoic acid OR DHA OR docosahexaenoic acid OR ALA OR alpha-linolenic acid

AND

-

(2)

dyslipidemia OR total cholesterol OR cholesterol OR LDL cholesterol OR HDL cholesterol OR triacylglycerol OR CRP

AND

-

(3)

heart disease OR CVD OR cardiovascular disease OR stroke OR diabetes OR obesity

This search returned 1341 results on PubMed. An initial screen of the title and abstract for relevancy was conducted based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Published between 1/1/2000 and 1/10/2013

Human participants

Article written in English

Adult participants aged >18 years

Exclusion criteria

In vitro studies

Participants were suffering from or had a history of chronic illness (i.e. CVD, type 2 diabetes, cancer, etc.)

Participants were medicated – not including hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

Reviews and meta-analyses

Based on the above, 514 published studies (collected by two independent researchers) were reviewed in detail and 207 clinical trials were identified for further consideration. The final list of clinical trials was selected based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria:

Healthy participants, defined as:

Healthy or moderately hyperlipidemic participants according to the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines [plasma lipid levels for borderline hyperlipidemic individuals are: 200 ≤ total-cholesterol (total-c) ≤ 240 mg/dL, 130 ≤ LDL-c ≤ 160 mg/dL, and 150 ≤ TG ≤ 200 mg/dL] [14, 25]

Healthy or overweight participants: Mean BMI within intervention group(s) and control/placebo group (if applicable) at baseline ≤29.9 kg/m2

Study end-points included blood lipid parameters (TG, total-c, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), LDL-c)*

Study must involve a dietary or supplement intervention with n-3 PUFA

Study duration was at least 2 weeks

Exclusion criteria

Participants that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were analyzed with participants that were explicitly stated to have not met the inclusion criteria

Endpoints were analyzed ex vivo

Low quality studies**

*Studies that did not report a baseline profile for total-c, LDL-c and/or TG were included in analysis if they fulfilled all remaining inclusion and exclusion criteria described above.

**Study quality was assessed by the Appraisal guide for intervention/experimental studies provided by Health Canada [26], if studies scored below a threshold of seven they were excluded from the current review (a single study scored below this threshold).

Applying these parameters yielded 38 clinical trials that were further stratified into dietary interventions (16 studies) and supplementation trials (22 studies).

Results

Dietary interventions

Using the indicated selection criteria, 16 dietary intervention studies (633 subjects in total) were deemed appropriate for the assessment of the impact of n-3 PUFA consumption on circulating TG and cholesterol levels within normolipidemic and borderline hyperlipidemic (otherwise healthy) adults (Table 1). It is noteworthy that two of the 16 studies [27, 28] were subsequent analyses of formerly identified interventions [29, 30]. Therefore, they are presented as single experiments in this review. As a result, a final list of 14 unique dietary intervention studies were assessed (Table 1). Among the 14 dietary intervention studies, four studies utilized increased fish consumption [31–34]; five studies examined the benefits of increasing EPA/DHA intake by enriching foods to contain a higher content of n-3 PUFA [27, 29, 35–38]; three studies measured the effects of increasing ALA intake [28, 30, 39, 40]; and 2 studies altered the n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio while maintaining a constant amount of n-3 PUFA consumption [41, 42]. Alterations from baseline plasma TG and cholesterol values were assessed in all 14 intervention studies in the current review. Overall, of the 24 experimental arms within the 14 studies, 15 showed reduced serum TG levels (five were statistically significant reductions; Table 2) and eight of the 14 studies showed reduced serum total-c, LDL-c or both (five were statistically significant reductions; Table 1). The three dietary interventions that provided ≥ 4 g/day of EPA and/or DHA noted significant reductions in TG of 9-26 % [27, 29, 31, 33], while six out of seven experimental arms providing 2.3-3.4 g/day of marine based n-3 PUFA produced non-significant reductions in TG of 3-14 % [32, 34, 42], and the effect of n-3 PUFA provided from flaxseed, flaxseed oil or ≤ 2 g/day of EPA and/or DHA remains ambiguous [28, 30, 35–40].

Table 1.

Studies assessing the lipid lowering effects of n-3 PUFA by dietary intervention

| Study | Subject Characteristics | n-3 PUFA Source (~dose/day) | Study Design | Duration | Lipid Outcomes | Other Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average baseline TG, Total-C, LDL-C (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Lara (2007) [31] | 16 males, 32 females | 125 g of salmon (5.4 g of n-3 PUFA) | Intervention (no placebo) | 4 week intervention; 4 week washout without fish | TG reduced 15 % (sig) | Blood pressure reduced 4 % (sig) |

| Scottish | LDL-c reduced 7 % | |||||

| 20–55 yrs old | ||||||

| Adiponectin reduced | ||||||

| (TG – 83, Total-C - 167, LDL-C - 92) | HDL-c elevated 5 % (sig) | |||||

| Hallund (2010) [32] | 68 males | 150 g of trout fed marine diet (3.4 g n-3 PUFA) | Randomized, parallel arm trial | 8 weeks | TG reduced 14 % and 6 % in participants consuming trout fed marine-based diet and trout fed a vegetable-based diet, respectively | Trout fed marine-based diet resulted in a reduction of blood pressure and CRP, compared to trout on vegetable diet |

| Danish | ||||||

| 40–70 yrs old | ||||||

| (TG – 102, Total-C - 189, LDL-C - 117) | Vs. | |||||

| 150 g of trout fed vegetable diet (0.8 g n-3 PUFA) | ||||||

| Ambring (2004) [33] | 12 males, 10 females | Mediterranean diet (4.1 g n-3 PUFA) | Randomized, cross-over trial | 4 week on one diet, 4 week washout, 4 week on opposite diet | TG reduced 9 % in the group receiving Mediterranean diet | Consumed fewer calories on Mediterranean vs. Swedish diet (1869 vs. 2090, respectively) |

| Swedish | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| 30–51 yrs old | Swedish diet (2.3 g n-3 PUFA) | Switching from a Swedish diet to a Mediterranean diet reduced serum TG, Total-c and LDL-c by 17 %, 17 % and 23 %, respectively (sig) | ||||

| (TG – 97, Total-C - 217, LDL-C - 139) | ||||||

| Source of n-3 PUFA in both diets was oily fish | ||||||

| Navas-Carretero (2009) [34] | 25 iron deficient females | Oily fish diet (2.8 g n-3 PUFA) | Randomized, cross-over trial | 8 weeks per diet | TG reduced 3.1 % while on fish diet | TG and HDL-c increased by 7.9 % and HDL-c by 1.2 % while on red meat diet |

| 18–30 yrs old | ||||||

| (TG – 60, Total-C - 173, LDL-C - 97) | Vs. | Total-c and LDL-c reduced 2.3 % and 7.5 %, respectively, while HDL-c increased by 7.2 %, while on fish diet (sig) | ||||

| Red meat diet (1.3 g n-3 PUFA) | ||||||

| Baro (2003) [35] | 15 males, 15 females (low background daily fish intake) | 500 ml of n-3 PUFA enriched semi-skimmed milk (0.33 g EPA + DHA) | Intervention (no placebo, initial values vs. final) | 4 week run in on low fish diet, 8 weeks consuming enriched milk | Total-c and LDL-c decreased 6 and 16 % (sig) | Homocysteine and VCAM-1 decreased by 13 % and 16 %, respectively |

| Spanish | ||||||

| 20–45 yrs old | ||||||

| (TG – 108, Total-C - 176, LDL-C - 91) | ||||||

| Dyerberg (2006) and Dyerberg (2004) [27, 29] | 79 males | Bakery products supplemented with 33 g of experimental fats: (a) 33 g control fat; | Randomized, double blind parallel arm trial | 8 weeks | TG reduced 26 % from baseline in the n-3 PUFA group. Change was significantly greater than the TG reduction observed in the control group. | The n-3 PUFA diet resulted in a 3 beat/min reduction in heart rate of subject with a normal heart rate variability |

| Danish | ||||||

| 20–60 yrs old | ||||||

| Vs. | HDL-c reduced in the group receiving soy oil compared to the control | |||||

| (TG – 102, Total-C - 185, LDL-C - 116) | (b) 12 g fish oil (4 g n-3 PUFA); | |||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| (c) 33 g soy oil (20 g trans FA) | ||||||

| Garcia-Alonso (2012) [36] | 18 females | 2 glasses of 250 ml n-3 PUFA-enriched tomato juice (500 mg EPA + DHA total) | Randomized, single blind, parallel arm trial | 2 weeks | No effect on lipid profile | Enriched juice reduced serum homocysteine, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 levels (sig) |

| Spanish | ||||||

| 35–55 yrs old | Vs. | |||||

| (TG – 59, Total-C - 197, LDL-C - 113) | Placebo | |||||

| Hamazaki (2003) [37] | 16 females, 25 males | 1 glass of 250 ml Soybean milk enriched with: | Randomized, double blind placebo controlled trial | 12 weeks | TG levels reduced 17 % (sig) in the group receiving the n-3 PUFA enriched soybean milk (no changes observed in the olive oil enriched milk) | |

| Japanese | ||||||

| 43–59 yrs old | Fish oil (0.6 g EPA + 0.26 g DHA) | |||||

| (TG – 154, Total-C - 211, LDL-C - 127) | Vs. | LDL-c levels did not change, while total-c elevated in both groups by 2 % | ||||

| Olive oil | ||||||

| Coates (2009) [38] | 29 males | 200 g portion of pork from pigs fed a diet fortified with n-3 (0.185 g n-3 PUFA) | Randomized, double-blind, parallel arm, placebo controlled trial | 12 weeks | TG levels reduced 27 % in the group consuming the n-3 PUFA fortified pork compared to controls | The n-3 PUFA fortified pork diet resulted in an elevation of serum thromboxane production (sig compared to the control) |

| 25–65 yrs old | ||||||

| (TG – 84) | ||||||

| Stuglin (2005) [39] | 15 males | 3 flaxseed-enriched muffins (6.67 g ALA total) | Intervention (no placebo, compared initial and final values) | 4 weeks | TG elevated 41 % (sig) | |

| Canadian | ||||||

| 22–47 yrs old | ||||||

| (TG – 124, Total-C - 172, LDL-C - 108) | ||||||

| Dodin (2008) and Dodin (2005) [28, 30] | 179 post-menopausal females | 2 slices of flaxseed bread (8.42 g ALA) | Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, parallel arm trial | 12 months | Flaxseed-enriched bread raised the participants’ serum TG 3 % | Flaxseed bread reduced BMI from baseline values (sig) |

| French Canadian | ||||||

| 49–65 yrs old | Vs. | LDL-c reduced in the group receiving flaxseed bread compared to the placebo | ||||

| (TG – 101, Total-C - 221, LDL-C - 134) | ||||||

| 2 slices of ground grain bread | ||||||

| Patenaude (2009) [40] | Group 1–10 females, 10 males | 1 muffin, enriched with either: | Randomized, double blind, parallel arm trial | 4 weeks | Diet (A) decreased total-c, LDL-c and TG by 7 %, 12 % and 11 % respectively, in Group 1. In group 2, Diet A decreased total-c and LDL-c 2 % while elevating TG by 13 % | Group 2 receiving diet B) had reduction in platelet aggregation (sig.) |

| 18–29 yrs old | ||||||

| (TG – 91, Total-C - 165, LDL-C - 78) | A) Ground flaxseed (6.5 g ALA) | |||||

| Group 2–10 females, 10 males | Vs. | |||||

| 45–69 yrs old | ||||||

| (TG – 81, Total-C - 181, LDL-C - 99) | B) Flaxseed oil (5.74 g of ALA) | Diet (B) decreased TG 20 % in Group 1, while elevating TG by 3.5 % in Group 2 | ||||

| Minihane (2005) [41] | 19 males | n-3 PUFA-enriched cooking oil and margarine (2 g n-3 PUFA) with either: | Randomized, double blind, parallel arm trial | 6 weeks | A diet containing a moderate ratio of n-6:n-3 PUFA resulted in 3 % and 8 % reductions in total-c and LDL-c, respectively, while increasing HDL-c by 8 % (0.05 < p < 0.1) | Diet providing a moderate ratio of n-6:n-3 PUFA increased total n-3 PUFA within RBC |

| Indian Asian (in the UK) | ||||||

| 35–70 yrs old | ||||||

| Diet providing a high ratio of n-6:n-3 PUFA increased plasma insulin levels and the participant’s HOMA-IR index (sig) | ||||||

| Moderate n-6:n-3 (15 g n-6 PUFA) | ||||||

| (TG – 140, Total-C - 192, LDL-C - 120) | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| High n-6:n-3 (26 g n-6 PUFA) | ||||||

| Sofi (2013) [42] | 12 males, 8 females | Gilthead sea bream fillets (2.3 g n-3 PUFA) fed either: Plant protein (2 g n-6 PUFA) Vs. | Randomized, single blind, cross-over trial | 15 day run in with no fish consumption, 10 weeks on fishmeal fed fish followed by 10 weeks on plant protein fed fish (or vice versa) | TG, total-c and LDL-c decreased 11.7 %, 29.3 % and 21.6 %, respectively, in group first receiving fishmeal fed fish (sig). Values rebounded to normal following second dietary intervention | Group first receiving fishmeal fed fish experienced reductions in IL-6 and IL-8, and improvements in RBC filtrate rate |

| Finish | ||||||

| 23–67 yrs old | ||||||

| Group A: fish fed fishmeal followed by fish fed plant protein each for 10 weeks | ||||||

| (TG – 117, Total-C - 233, LDL-C - 152) | ||||||

| Fishmeal (1 g n-6 PUFA) | ||||||

| The group initially receiving plant protein fed fish experienced reductions in cholesterol occurring 10 weeks after subsequently fed fish fed fishmeal | ||||||

| Group B: fish fed plant protein followed by fish fed fishmeal each for 10 weeks | ||||||

| (TG – 94, Total-C - 216, LDL-C - 139) |

Table 2.

Alteration of serum TG levels in dietary intervention studies involving normolipidemic and moderately hyperlipidemic subjects

| Study | N-3 PUFA Dose (g/d) | % Change in serum TG levels | Duration (wks) | Additional Dietary Modifications | Study | N-3 PUFA Dose (g/d) | % Change in serum TG levels | Duration (wks) | Additional Dietary Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normolipidemic Subjects – Modified EPA and/or DHA Intake | Moderately Hyperlipidemic Subjects – Modified EPA and/or DHA Intake | ||||||||

| Lara [31] | 5.4 | −15* | 4 | Salmon Based | Ambring [33] | ||||

| Dyerberg [27, 29] | 4 | −26* | 8 | Group A | 4.1 | −9* | 4 | Mediterranean Based | |

| Hallund [32] | Group B | 2.3 | 9 | 4 | Swedish Based | ||||

| Group A | 3.4 | −14 | 8 | Trout Based | Sofi [42] | ||||

| Group B | 0.8 | −6 | 8 | Trout Based | Group A | 2.3 | −2 | 10 | High LA diet |

| Navas-Carretero [34] | 2.8 | −3.1 | 8 | Oily Fish Based | Group B | 2.3 | −2 | 10 | Moderate LA diet |

| Minihane [41] | Group C | 2.3 | −12 | 10 | Moderate LA diet | ||||

| Group A | 2 | 3 | 6 | Moderate LA diet | Group D | 2.3 | −2 | 10 | High LA diet |

| Group B | 2 | −5 | 6 | High LA diet | Hamazaki [37] | 0.86 | −17* | 12 | |

| Garcia-Alonso [36] | 0.5 | 0 | 2 | ||||||

| Baro [35] | |||||||||

| Group A | 0.33 | 2 | 8 | ||||||

| Group B | 0.33 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| Coates [38] | 0.185 | −27* | 12 | ||||||

| Normolipidemic Subjects – Modified ALA Intake | Moderately Hyperlipidemic Subjects – Modified ALA Intake | ||||||||

| Stuglin [39] | 6.98 | 41* | 4 | Ground Flaxseed | Dodin [28, 30] | 8.53 | 3 | 52 | Ground Flaxseed |

| Patenaude [40] | |||||||||

| Group A | 6.5 | −11 | 4 | Ground Flaxseed | |||||

| Group B | 6.5 | 13 | 4 | Ground Flaxseed | |||||

| Group C | 5.74 | −20 | 4 | Flaxseed Oil | |||||

| Group D | 5.74 | 4 | 4 | Flaxseed Oil | |||||

*Asterisks denotes studies which found significantly different changes in serum TG levels (p < 0.05)

TG and LDL-c were only significantly lowered in interventions providing more than 4 g/day of n-3 PUFA through increased fish consumption. Two trials, of 4 weeks [31] and 8 weeks in duration [32], showed that fish consumption of 125–150 g/day (3.4-5.4 g/day of n-3 PUFA) reduced TG levels by 14-15 %. The 4-week intervention also showed a statistically non-significant 7 % reduction in LDL-c [31]. Another study demonstrated that switching from a Swedish diet to a Mediterranean diet (2.3 g vs. 4.1 g/day of n-3 PUFA) for 4 weeks resulted in statistically significant 17 %, 23 % and 17 % reductions in serum total-c, LDL-c and TG, respectively [33]. Finally, participants consuming an oily fish diet (2.6-3.0 g/day of n-3 PUFA) for 8 weeks experienced non-significant reductions in total-c and LDL-c by 2.3 % and 7.5 %, respectively, and a trend towards lowered TG levels (by 3.1 %) was observed when compared to a red meat diet (1.2-1.4 g/day of n-3 PUFA) [34].

There were five studies designed to increase EPA and/or DHA consumption through enriched baked goods [27, 29], drinks [35–37], or pork derived from animals consuming marine based n-3 PUFA-enriched food [38]. Two 12 week studies, one providing 0.86 g/day of n-3 PUFA from enriched milk and the other providing 0.185 g/day of n-3 PUFA from enriched pork, produced significant reductions in serum TG of 17 % and 27 %, respectively, while not significantly altering serum cholesterol levels [37, 38]. One 8-week intervention providing 0.33 g/day of n-3 PUFA from enriched milk showed a reduction in total-c and LDL-c of 6 % and 16 %, respectively [35]; while a second 8-week study providing 4 g/day of n-3 PUFA from enriched baked goods produced a statistically significant 26 % reduction in TG levels [27, 29]. In contrast, a 2-week study providing 0.5 g/day of n-3 PUFA from EPA/DHA enriched tomato juice did not report any changes in TG or cholesterol levels, however, participants show significant reductions in circulating homocysteine, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 [36].

Studies assessing an increased consumption of ALA utilized 30–40 g/day of flaxseed (5.74-8.42 g/day of ALA) [28, 30, 39, 40], yet the results from these trials produced inconsistent effects on lipid levels. For instance, a 4-week intervention with 32.7 g/day of ground flaxseed led to a 41 % increase in TG levels [39]. In contrast, a 12-month intervention, providing 40 g/day of flaxseed, resulted in the maintenance of cholesterol and TG levels, while the placebo significantly elevated plasma total-c and LDL-c levels [28, 30]. Additionally, one 4-week intervention that provided participants with 5.74-6.5 g/day of ALA found non-significant reductions in serum lipids [40]. Interestingly, although non-significant, the consumption of ground flaxseed or flaxseed oil (each providing an equal amount of ALA) resulted in 11 % and 20 % reductions in TG levels, respectively, in individuals 18–29 years of age; ground flaxseed also led to 7 % and 12 % reductions in total-c and LDL-c, respectively [40].

All of the previously mentioned studies reduced an individual’s dietary n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio by elevating n-3 PUFA consumption. However, two studies investigated the effects of altering the n-6:n-3 PUFA dietary ratio by increasing n-6 PUFA intake while maintaining a constant n-3 PUFA intake. This allowed for the investigation into whether a reduced n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio alone is more beneficial than an absolute increase in n-3 PUFA consumption as well as a decreased dietary n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio, as evaluated in the previous studies. One study accomplished this by replacing monounsaturated fatty acids with n-6 PUFA; participants either consumed a moderate or high ratio of n-6:n-3 PUFA consisting of 15 g or 26 g/day, respectively, of n-6 PUFA while consistently consuming 2 g/day of n-3 PUFA for 6 weeks [41]. While there were no statistically significant differences between treatments, the diet providing 15 g of n-6 PUFA produced a trend towards reduced total-c and LDL-c by 3 % and 8 %, respectively, and a trend towards elevated HDL-c by 8 % [41]. During a 10-week cross-over study, participants consumed 90 g/day of fishmeal- or plant protein-fed gilthead sea bream that provided either 1 g or 2 g/day of n-6 PUFA, respectively, while consistently providing 2.3 g/day of n-3 PUFA [42]. This study showed that individuals who first consumed the fishmeal-fed gilthead sea bream had a reduction in total-c, LDL-c and TG by 29.3 %, 21.6 % and 11.7 %, respectively, prior to rebounding after 10 weeks of consuming plant protein-fed fish [42]. However, participants who first consumed the plant protein-fed fish did not experience reductions in any lipid markers following either dietary intervention, except for a 5 % reduction in total-c following the cross over period [42].

Supplementation studies

Using the selection criteria previously described, 22 clinical trials (1637 subjects in total) utilizing n-3 PUFA in a supplement form were evaluated in the current review (Table 3). These trials assessed the effect of n-3 PUFA supplementation on blood lipid profiles in individuals with normal and borderline high levels of TG, total-c, and LDL-c. These studies included participants from ages 18 to 75 years, with a treatment duration ranging from 2 to 52 weeks. The main source of n-3 PUFA from these studies was fish oil [43–59], which provided an approximate EPA:DHA ratio of 1.5:1. Five studies utilized a DHA-rich oil from an algal source [59–63], and two studies employed an EPA-rich oil from fish sources [59, 64]. The studies encouraged participants to consume n-3 PUFA supplements in the form of 1 to 12 capsules per day while maintaining normal dietary habits. Supplementation provided 0.3-4.9 g/day of n-3 PUFA. As shown in Table 4, fasting TG levels were reduced following supplementation with EPA and/or DHA exclusively in 30/34 experimental arms within the 22 studies (i.e. 88 % of the interventions evaluated, without taking statistical significance into account) and post-supplementation TG levels were significantly lowered from baseline in 23 of the 34 aforementioned experimental arms (i.e. 68 % of the interventions; however, one study did not analyze for an in-group difference in serum lipid levels from baseline to post-supplementation [62]).

Table 3.

Studies assessing the lipid lowering effects of n-3 PUFA utilizing a supplement

| Study | Subject Characteristics | n-3 PUFA Source and Dose | Study Design | Duration | Lipid Outcomes | Other Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average baseline TG, Total-C, LDL-C (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Fakhrzadeh (2010) [43] | 73 females, 51 males | 1 capsule of fish oil | Randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, parallel arm | 26 weeks | TG levels increased 15 % in the placebo group and decreased 2 % in the treatment group (sig. between group effect) | |

| Age: 65+ | ||||||

| (TG – 145, Total-C - 190, LDL-C - 114) | 0.18 g EPA + 0.12 g DHA | LDL-c, HDL-c, or total-c did not change | ||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| Placebo | ||||||

| Sanders (2011) [44] | 225 female, 142 males | 3 capsules of fish oil (1:5 ratio of EPA:DHA) containing: | Randomized, placebo controlled, parallel arm, double-blind | 52 weeks | TG levels reduced 16.5 % by 1.8 g/day, and was unchanged in both 0.45 g/day and 0.9 g/day (sig) | No change in blood pressure, arterial stiffness, or measures of endothelial function after supplementation |

| Age: 45–70 | ||||||

| (TG – 100, Total-C - 210, LDL-C - 125) | a) 0.45 g n-3 PUFA | |||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| b) 0.9 g n-3 PUFA | Total-c , HDL-c and LDL-c was unchanged after supplementation at each dose | |||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| c) 1.8 g n-3 PUFA | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| Placebo | ||||||

| Hlais (2013) [45] | 112 males | Fish oil (FO) capsules (Per gram: 0.737 g of n-3 PUFA: 0.495 g EPA + 0.196 g DHA): | Randomized, single blind, parallel arm study | 6 and 12 weeks | After 6 weeks : | No significant effects on glycemic and blood pressure parameters were noted |

| Age: 18–35 | ||||||

| (TG – 125, Total-C - 187, LDL-C - 118) | A) 2 g of FO | TG was reduced by 15 %, 4 %, 10 % in Groups A, B, D, respectively, and elevated by 6 %, 3 % in Groups C, E, respectively (only group A was sig) | ||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| B) 1 g of FO and 8 g of sunflower oil | ||||||

| Vs. | Total-c and LDL-c was elevated by 2-8 % in Groups A, B, C, E (non-sig) and by 7 % and 13 % in Group D, respectively (sig) | |||||

| C) 2 g of FO and 8 g of sunflower oil | ||||||

| Vs. | HDL-c was elevated by 4-6 % in Groups A, C, D and reduced by 10 % and 3 % in Groups B, E, respectively (non-sig) | |||||

| D) 4 g of FO and 8 g of sunflower oil | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| After 12 weeks : | ||||||

| TG was reduced by 12 %, 12 %, 2 %, 5 % in Groups A, B, D, E respectively, and elevated by 1 % in Groups C (non-sig) | ||||||

| Total-c was elevated by 4 % in Groups A, D, and reduced by 1 %, 4 % and 10 % in groups B, C, E, respectively (only Group E was sig) | ||||||

| E) 8 g of sunflower oil | LDL-c was elevated by 3-7 % in Groups A, B, D (non-sig) and reduced by 5 % and 13 % in Group C, E, respectively (only Group E was sig) | |||||

| HDL-c was elevated by 6 %, 2 % in Groups A, D, respectively, and reduced by 5-7 % in Groups B, C, E, (non-sig) | ||||||

| Nilsson (2012) [46] | 28 females, 10 males | 5 capsules of fish oil | Randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study | 5 weeks | TG reduced 12 % (sig) | Systolic and Diastolic blood pressure was reduced by 5 % |

| Age: 51–72 | 1.5 g EPA, 1.05 g DHA, and 0.45 g of other n-3 PUFA | |||||

| (TG – 142) | ||||||

| Inflammatory markers were unchanged | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| Placebo | ||||||

| Rizza (2009) [47] | 25 females, 25 males | 2 capsules of fish oil (0.6 g EPA, 0.4 g DHA per capsule) | Randomized, double-blind, parallel designed, placebo controlled | 12 weeks | TG levels reduced 26 % with treatment (sig) | Improvement in flow mediated dilation in treatment group |

| Age: 29.9+/− 6.6 | ||||||

| (TG – 118, Total-C - 192, LDL-C - 122) | Vs. | HDL-c, LDL-c and total-c did not change | ||||

| Placebo | ||||||

| Lovegrove (2004) [48] | 84 Males | 4 capsules of fish oil | Randomized, double bind, placebo controlled, parallel arm | 12 weeks | TG was reduced 31 % (sig) | |

| Age: 30–70 | 1.5 g EPA, 1.0 g DHA | HDL-c increased (sig) | ||||

| (TG – 128, Total-C - 207, LDL-C - 128) | Vs. | No effect on total-c or LDL-c was observed | ||||

| Placebo | ||||||

| Ciubotaru (2003) [49] | 30 Post Menopausal Females on Hormone Replacement Therapy | Fish oil | Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled | 5 weeks | TG reduced 26 % in group receiving 14 g of fish oil (sig) and 4 % in group receiving 7 g of fish oil | CRP reduced, IL-6 reduced in groups receiving fish oil supplements |

| Randomized to three groups: | ||||||

| Age: 60+/− 5 | a) 14 g safflower oil (0 g EPA/DHA) | |||||

| (TG – 121, Total-C - 220, LDL-C - 126) | ||||||

| Vs. | Group receiving safflower oil alone experienced a 21 % increase in TG levels | |||||

| b) 7 g safflower oil + 7 g fish oil (1.45 g EPA + DHA) | ||||||

| No change in LDL-c or total-c | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| 14 g fish oil | ||||||

| (2.9 g EPA+ DHA) | ||||||

| Offman (2013) [50] | 15 Females, 37 Males | Fish oil: 4 g of Epanova or 4 g of Lovaza | Open label, parallel group cohorts | 2 weeks | Participants receiving Epanova had reductions in TG, HDL-c and LDL-c of 21 %, 5 % and 4 %, respectively | Epanova raised plasma total EPA + DHA concentrations 3 times the level as subject’s receiving Lovaza |

| Age: 18–55 | ||||||

| (TG – 166, Total-C - 189, LDL-C - 128) | Lovaza: 1.8 g of EPA, 1.5 g of DHA | |||||

| Participants receiving Lovaza had reductions in TG and HDL-c levels of 8 % and 7 %, respectively, while raising LDL-c by 0.4 % | ||||||

| Epanova: 2.2 g of EPA and 0.8 g of DHA | ||||||

| (effects on TG between groups were significant) | ||||||

| Laidlaw (2003) [51] | 31 Females | Fish oil capsules (4 g of EPA + DHA) with: | Randomized, parallel arm study | 4 weeks | TG was reduced 35-40 % in groups receiving 0 g, 1 g and 2 g of GLA (sig), and TG was reduced 7 % in the group receiving 4 g of GLA | |

| Age: 36–68 | ||||||

| (TG – 112, Total-C - 213, LDL-C - 134) | 0 g of gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) | |||||

| Vs. | All groups had reductions in total-c of 1-9 % | |||||

| 1 g of GLA | LDL-c was reduced in all groups by 2-13 %, except in the group receiving 1 g of GLA (only sig in the group receiving 2 g of GLA) | |||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| 2 g of GLA | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| 4 g of GLA | ||||||

| Mann (2010) [52] | 19 Females, 11 Males | 10 capsules containing: | Randomized, double-blind, parallel designed study | 2 weeks | TG was reduced 25 % in the group receiving Seal oil and 21 % in the group receiving Tuna oil (sig) | CRP was reduced by 11 % and 25 % in the groups receiving tuna oil and fish oil, respectively |

| Age: 20–50 | Tuna oil (0.21 g of EPA, 0.03 g of DPA, 0.81 g of DHA) | |||||

| (TG – 120, Total-C - 196, LDL-C - 134) | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| Seal oil (0.34 g of EPA, 0.23 g of DPA, 0.45 g of DHA) | LDL-c was elevated through both interventions by 3 % | |||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| Placebo | ||||||

| Vanschoonbeek (2004) [53] | 20 Males | 9 capsules of fish oil:1.05 g EPA, 0.75 g, DHA, and 1.2 g other n-3 PUFA | Intervention (no placebo, compared initial vs. final values) | 4 weeks | TG was reduced 10 % (sig) | Treatment lowered integrin activation, as well as plasma levels of fibrinogen and factor V |

| Age: 48.5+/− 9.8 | Total-c was unchanged | |||||

| (TG – 141, Total-C - 218, LDL-C - 151) | LDL-c increased 5 % and remained borderline high | |||||

| Di Stasi (2004) [54] | 18 Females, 18 Males | Fish Oil Capsules (46 % and 39 % of n-3 PUFA was EPA and DHA, respectively): | Randomized, parallel arm study | 12 weeks | There was no significant change in TG levels from baseline within each group, however, a significant dose response was noted. n-3 PUFA provided at 2 g and 4 g per day resulted in TG reductions by 15 and 20 %, respectively. | |

| Age: 21–51 | ||||||

| (TG – 87, Total-C - 211) | ||||||

| 1 g of n-3 PUFA/day | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| 2 g of n-3 PUFA/day | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| 4 g of n-3 PUFA/day | ||||||

| Stark (2000) [55] | 35 Postmenopausal Females | 8 Fish Oil capsules: | Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, cross-over study | 4 weeks | n-3 PUFA produced a 26 % reduction in serum TG levels (sig) | |

| 2.4 g EPA + 1.6 g of DHA | n-3 PUFA produced a 5 % increase in LDL-c levels | |||||

| Age: 43–60 | Vs. | |||||

| (TG – 120, Total-C - 213, LDL-C - 122) | ||||||

| Placebo (primrose oil) | ||||||

| Damsgaard (2008) [56] | 66 males | 10 capsules of fish oil (2.0 g EPA, 1.25 g DHA) | Randomized, double-blind placebo controlled, 2x2 factorial design | 8 weeks | TG levels were reduced 19 % with high LA intake (sig) and 51 % reduction with low LA intake (sig) | -No change in inflammatory markers |

| Age: 19–40 | ||||||

| (TG – 89, Total-C - 153, LDL-C - 99) | Vs. | |||||

| Placebo | ||||||

| Supplementation with either high LA in diet or low LA in diet | No changes in HDL-c, LDL-c, total-c | |||||

| Brady (2004) [57] | 29 Males | fish oil capsules | Double-blind, parallel, dietary intervention | 6 weeks | TG was reduced 20 % and 25 % in high and moderate groups, respectively (sig) | |

| Age: 35–70 | (2.5 g EPA+ DHA) with either: | |||||

| Moderate n-6 PUFA diet (olive oil) | ||||||

| No changes in HDL-c, LDL-c, total-c | ||||||

| (TG – 137, Total-C - 186, LDL-C - 114) | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| High n-6 PUFA diet (corn oil) | ||||||

| Kaul (2008) [58] | 54 females, 34 males | 2, 1 g capsules per day containing | Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, parallel arm study | 12 weeks | Fish oil produced a 4 % and 7 % increase in total-c and LDL-c, respectively | No significant change in CRP or TNF-ɑ levels |

| Age: 31–36 | ||||||

| (TG – 113, Total-C - 184, LDL-C - 102) | Fish oil (0.606 g of n-3 PUFA; 0.242 g of DHA + 0.352 g of EPA) | Flaxseed oil produced a 4 % and 12 % increase in total-c and LDL-c, respectively | No significant change in platelet aggregation stimulated by thrombin or collagen | |||

| Hempseed oil produced a 4 % increase in both total-c and LDL-c and an 18 % increase in TG | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| Flaxseed oil (1.02 g of ALA) | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| Hempseed oil (0.372 g of ALA,1.14 g of LA) | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| Sunflower oil (1.36 g of LA) | ||||||

| Buckley (2004) [59] | 20 Females, 22 Males | 9 capsules of EPA or DHA-rich oil | Randomized, double bind, placebo controlled, parallel arm | 4 weeks | EPA treatment: TG decreased 22 % (sig) | |

| Age: 20–70 | ||||||

| 4.8 g EPA | ||||||

| (TG – 106, Total-C - 205, LDL-C - 124) | Vs. | DHA treatment: TG decreased 38 % (sig) | ||||

| 4.9 g DHA | Total-c decreased (p = 0.06) | |||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| Placebo | No changes in LDL-c or HDL-c | |||||

| Sanders (2006) [60] | 40 Females, 39 Males | 4 capusles of DHA-rich oil from Schizochytrium sp. | Randomized double bind, placebo controlled, parallel arm | 4 weeks | TG decreased from baseline 14 % (sig) | |

| Age: 31 +/− 14 | No changes in total-c or LDL-c levels | |||||

| (TG – 89, Total-C – 175, LDL-C – 96) | 1.5 g DHA + 0.6 g DPA | |||||

| Vs. | HDL-c increased by 9 % (sig) | |||||

| Placebo | ||||||

| Stark (2004) [61] | 32 Postmenopausal Females | 12, 500 mg Capsules containing DHA from an algal source | Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, cross-over study | 4 weeks | DHA decreased TG by 8 % (sig). | DHA was able to reduce resting heart rate by 7 % |

| Age: 45–70 | ||||||

| 2.8 g of DHA | DHA elevated HDL-c by 8 %, total-c by 4 % and reducing LDL-c by 8 % | |||||

| (TG - 132, Total-C – 216, LDL-C – 125) | Vs. | |||||

| Placebo (corn and soy oil mixture) | ||||||

| Wu (2006) [62] | 25 Postmenopausal Vegetarian Females | Capsules providing 6 g of DHA rich algae oil | Randomized, single blind, placebo controlled study | 6 weeks | DHA decreased TG by 18 %, Total-c by 3 % and LDL-C by 3 % while elevating HDL-C by 6 % | No changes in levels of urinary estrogen metabolites, or markers of oxidative stress (e.g. ɑ-tocopherol) |

| Age: 52 +/− 5 yrs | 2.4 g of DHA | |||||

| (TG - 124, Total-C – 158, LDL-C - 90) | ||||||

| Vs. | *Only between group analysis was performed | |||||

| Placebo (corn oil) | ||||||

| Geppert (2006) [63] | 87 Females, 87 Males Vegetarians | 4 capusles of DHA-rich oil from Ulkenia sp. | Randomized, double blind, parallel design, placebo controlled | 8 weeks | TG reduced 23 % in the group receiving DHA rich oil (sig). | No significant changes in haemostatic factors |

| Age: 28–43 | 0.94 g of DHA | Total cholesterol, LDL-c and HDL-c increased 6-11 % in the group consuming DHA rich oil (sig) | ||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| (TG - 95, Total-C – 180, LDL-C – 97) | ||||||

| Placebo (olive oil) | ||||||

| No changes in the placebo group | ||||||

| Cazzola (2007) [64] | 93 Young Males, 63 Older Males | 9 capsules of EPA-rich fish oil containing either: | Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled | 12 weeks | TG levels were reduced ~25 % after 1.35, 2.7 or 4.05 g of EPA across all ages (sig) | EPA supplementation tended to decrease soluble ICAM-1 |

| a) 1.35 g EPA | ||||||

| Age: Young, 18–42; Old, 53–70 | Vs. | |||||

| b) 2.7 g EPA | ||||||

| (TG - 82, Total-C – 162, LDL-C – 103) | Vs. | No effect on HDL-c, LDL-c, or total-c in any group | ||||

| c) 4.05 g EPA | ||||||

| Vs. | ||||||

| Placebo |

Table 4.

Alteration of serum TG levels in supplementation studies involving normolipidemic and moderately hyperlipidemic subjects

| Study | N-3 PUFA Dose (g/d) | % Change in serum TG levels | Duration (wks) | Additional Supplement (g/d) | Study | N-3 PUFA Dose (g/d) | % Change in serum TG levels | Duration (wks) | Additional Supplement (g/d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normolipidemic Subjects - EPA and/or DHA Supplements | Moderately Hyperlipidemic Subjects – EPA and/or DHA Supplements | ||||||||

| Cazzola [64] | Buckley [59] | ||||||||

| Group A | 4.05 | −30* | 12 | Group A | 4.9 | −8* | 4 | ||

| Group B | 4.05 | −25* | 12 | Group B | 4.8 | −22* | 4 | ||

| Group C | 2.7 | −25* | 12 | Laidlaw [51] | |||||

| Group D | 2.7 | −33* | 12 | Group A | 4 | −40* | 4 | ||

| Group E | 1.35 | −22* | 12 | Group B | 4 | −39* | 4 | 1 g of γ-linolenic acid | |

| Group F | 1.35 | −33* | 12 | Group C | 4 | −35* | 4 | 2 g of γ-linolenic acid | |

| Damsgaard [56] | Group D | 4 | −7 | 4 | 4 g of γ-linolenic acid | ||||

| Group A | 3.25 | −51* | 8 | Low LA diet | Di Stasi [54] | ||||

| Group B | 3.25 | −19* | 8 | High LA diet/Olive Oil | Group A | 4 | −20 | 12 | |

| Nilsson [46] | 3 | −12* | 5 | Group B | 2 | −15 | 12 | ||

| Hlais [45] | Group C | 1 | 9 | 12 | |||||

| Group A | 2.95 | −10 | 6 | 8 g of Sunflower Oil | Stark [55] | 4 | -26* | 4 | |

| Group B | 2.95 | −2 | 12 | 8 g of Sunflower Oil | Offman [50] | ||||

| Group C | 1.47 | −15* | 6 | Group A | 3.3 | −8 | 2 | ||

| Group D | 1.47 | 6 | 6 | 8 g of Sunflower Oil | Group B | 3 | −21 | 2 | |

| Group E | 1.47 | −12 | 12 | Vanschoonbeek [53] | 3 | −10* | 4 | ||

| Group F | 1.47 | 1 | 12 | 8 g of Sunflower Oil | Ciubotaru [49] | ||||

| Group G | 0.74 | −4 | 6 | 8 g of Sunflower Oil | Group A | 2.9 | −26* | 5 | |

| Group H | 0.74 | −12 | 12 | 8 g of Sunflower Oil | Group B | 1.45 | −4 | 5 | 7 g of Safflower Oil |

| Brady [57] | Stark [61] | 2.8 | −20* | 4 | |||||

| Group A | 2.5 | −25* | 6 | Moderate LA diet/Olive Oil | Lovegrove [48] | 2.5 | −31* | 12 | |

| Group B | 2.5 | −20* | 6 | High LA diet - Corn Oil | Sanders [44] | ||||

| Wu [62] | 2.4 | −18* | 6 | Group A | 1.8 | −17* | 52 | ||

| Sanders [60] | 2.1 | −21 | 4 | Group B | 0.9 | 0 | 52 | ||

| Rizza [47] | 2 | −26* | 12 | Group C | 0.45 | 0 | 52 | ||

| Geppert [63] | 0.94 | −23* | 8 | Mann [52] | |||||

| Kaul [58] | Group A | 1.05 | −21* | 2 | |||||

| Group A | 0.61 | 0 | 12 | Group B | 1.02 | −25* | 2 | ||

| Fakhrzadeh [43] | 0.3 | −2 | 26 | ||||||

| Normolipidemic Subjects - ALA Supplements | |||||||||

| Kaul [58] | |||||||||

| Group B | 1.02 | 0 | 12 | Flaxseed Oil; 0.28 g of LA | |||||

| Group C | 0.37 | 15 | 12 | Hempseed Oil; 1.02 g of LA | |||||

*Asterisks denotes studies which found significantly different changes in serum TG levels (p < 0.05)

The magnitude of the n-3 PUFA-mediated TG-lowering effect varied depending on the supplementation dose and the study duration. Low doses such as 0.3-0.9 g/day of n-3 PUFA for 12–52 weeks did not consistently produce a significant reduction in TG levels [43–45, 63]. While studies solely providing n-3 PUFA in doses < 1 g/day (EPA, DHA or both) significantly lowered fasting TG by 8-38 % [44–55, 59, 61, 62, 64]. In a dose–response study, 1.8 g/day of EPA and DHA for 52 weeks was sufficient to lower TG levels by 16.5 %, whereas 0.45 and 0.9 g/day did not affect fasting TG levels [44]. A second study demonstrated a significant dose–response effect whereby 1 g/day of marine derived n-3 PUFA produced an elevation in TG levels by 9 %, while 2 and 4 g/day of n-3 PUFA for 12 weeks produced decreases in TG levels of 15 % and 20 %, respectively [54]. However, none of the aforementioned doses produced a significant change from baseline values [54].

Two studies investigated the effect of fish oil based n-3 PUFA supplementation combined with a background diet that was either high or moderate in n-6 PUFA, specifically linoleic acid (18:2 n-6, LA) [56, 57]. In an 8 week study, 3.1 g/day of n-3 PUFA resulted in a 19 % and a 51 % reduction in TG levels while consuming either a high or moderate n-6 PUFA background diet, respectively [56]. Similarly, participants of a 6 week study, stratified to a high or moderate LA background diet found that 2.5 g/day of EPA and DHA benefited both groups with similar reductions in TG levels of 20 % and 25 %, respectively [57].

Studies that utilized an algal source of DHA consistently demonstrated the TG-lowering effects of the supplement [59–63]. Three 4-week studies, providing 1.5, 2.8 and 4.9 g/day of DHA, found significant reductions in TG levels of 14 %, 8 % and 38 %, respectively [59–61]. Further, a 6-week study providing 2.4 g/day of algal-derived DHA showed a significant 18 % reduction in TG levels compared to a placebo [62]. Additionally, a study providing only 0.94 g/day of DHA, but for 8 weeks, noted a significant 23 % reduction in TG levels [63].

Blood cholesterol levels were also examined in the 22 supplementation studies within the current review, and only two studies [48, 60] observed modest n-3 PUFA-induced increases in HDL-c levels that were significantly different from baseline. Thus, total-c, LDL-c, and HDL-c remained largely unchanged with n-3 PUFA supplementation. A modest reduction in total-c occurred with 4.9 g/day of DHA, yet this difference was not statistically significant [59]. Additionally, only 1 study produced a significant 11 % reduction in LDL-c levels following 4 weeks of supplementation with 4 g/day of n-3 PUFA, however, this effect was produced with an additional 2 g/day supplement of gamma-linolenic acid (18:3 n-6, GLA) [51].

Discussion

This review indicates that the established TG-lowering effect of n-3 PUFA in hyperlipidemic individuals is maintained within populations who are normolipidemic to borderline hyperlipidemic. Studies in which participants consumed EPA and/or DHA or fish consistently reported lower blood TG levels in comparison to those studies in which participants consumed plant-based sources of n-3 PUFA. Overall, the studies involving dietary interventions evaluated within the current review suggest that a TG-lowering effect of marine based n-3 PUFA is produced in healthy individuals upon the consumption of ≥ 4 g/day of n-3 PUFA. In contrast, the supplementation studies assessed within the current review suggest that a minimum of 1 g/day of EPA and/or DHA (derived from either fish or algal oil) is required to confer a similar benefit as observed in the dietary interventions.

Within the past 5 years, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the AHA and the Food Standards - Australia and New Zealand (FSANZ) organization have all recognized n-3 PUFA as a preventative measure against the development of CVD, primarily by reducing risk factors for CVD, including elevated blood TG levels [12–15]. The EFSA established and substantiated a health claim in 2010 indicating the consumption of 2 g of EPA/DHA per day has the ability to maintain normal blood TG concentrations [12, 13]. Furthermore, the AHA released a statement in 2011 indicating that a daily dosage of 2–4 g of n-3 PUFA, specifically EPA and DHA, confers a 25-30 % decrease in serum TG levels [14].

The health claim by the EFSA and the statement by the AHA are largely based on the findings of a systematic review by W.S. Harris [19]. This review stratified studies comparing participants with either healthy (serum levels < 177 mg/dL) or elevated levels (serum levels ≥ 177 mg/dL) of serum TG; relative to the upper limit for serum TG of 200 mg/dL utilized in the current review [19]. However, in the review by Harris, a quarter of the studies assessing participants with healthy baseline TG levels contained a hypercholesterolemic population (serum TC ≥ 240 mg/dL). Nonetheless, the results indicated that 3–4 g/day of EPA and/or DHA produced a 25-34 % decrease in serum TG levels [19]. This finding is supported by a later systematic review which reported that individuals with either borderline high or high levels of serum TG (according to AHA guidelines) experienced reductions in TG levels of ~20 % and ~30 %, respectively, when consuming 4 g/day of EPA and/or DHA [18].

The previous reviews indicate that marine based n-3 PUFA can reduce serum TG levels; however, they primarily focused on supplementation studies within dyslipidemic populations. An earlier review by W. S. Harris, than the 1997 study previously discussed, included dietary intervention studies and produced findings similar to those of the current review. Overall, consuming n-3 PUFA through dietary forms primarily showed a trend in TG reductions, while a significant effect was only observed when large amounts of n-3 PUFA were consumed (as observed in Table 2, ≥ 4 g/day of n-3 PUFA) and the effects of ALA supplementation were highly variable [17]. W. S. Harris concluded that this inconsistency in the ability of n-3 PUFA to reduce serum TG levels during dietary interventions was likely due to the manipulation of multiple variables as the food source was not highly controlled between studies [19]. The lack of a consistent study design for elevating n-3 PUFA consumption through dietary modifications continues to be a limitation for the field. This constraint reduces the ability to evaluate an exact dosage and source of EPA and/or DHA required to significantly, and routinely, lower serum TG levels across all populations.

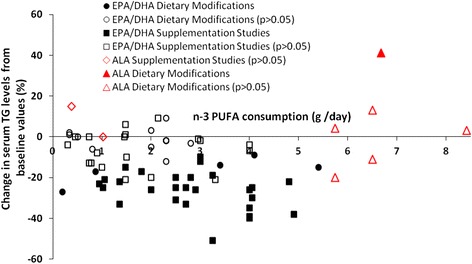

Several reviews have repeatedly shown an effect of EPA and/or DHA in lowering TG levels during supplementation trials [17, 19–24]. Based on the current review, when ≥ 1 g/day of EPA and/or DHA is consumed by individuals, without any other increases in dietary fat intake, an 8-40 % reduction in TG levels can be observed, as shown in Table 4. The apparent presence of a lipid-lowering dose–response to marine derived n-3 PUFA intake, demonstrated in the study by Di Stasi et al. [54], suggests additional benefits are attainable when supplementation is raised as high as 4.9 g/day [54]. Figure 2 summarizes the TG-lowering effects of individuals consuming ALA, EPA, DHA or some combination of these n-3 PUFA within the studies analyzed in this review. This figure highlights the consistent lipid-lowering effect of EPA and DHA; studies providing ALA remain inconclusive. Additionally, Fig. 2 indicates that as the dose of EPA and/or DHA increases, in both supplementation and dietary intervention studies, a concurrently larger reduction in TG levels is obtained. Furthermore, Fig. 2 shows neither EPA and/or DHA significantly raised TG levels from baseline in either supplementation or dietary intervention studies.

Fig. 2.

The percent change in serum TG levels from baseline values in normolipidemic and borderline hyperlipidemic subjects receiving n-3 PUFA either through the diet or supplemental forms. Shaded markers indicate changes from baseline that are statistically significant (p < 0.05)

Based on the present review, the beneficial effects of n-3 PUFA, specifically EPA and DHA, which have been substantiated in hyperlipidemic individuals, extend to individuals with normal to borderline high levels of serum lipids. In summary, using select search terms and criteria, our review of the existing evidence has shown that consumption of ≥ 4 g/day of n-3 PUFA through marine and EPA and/or DHA-enriched food sources, or 1–5 g/day of EPA and/or DHA in supplement form, has the ability to reduce serum TG by 9-26 % and 4-51 %, respectively, in normolipidemic to borderline hyperlipidemic and otherwise healthy individuals. This provides evidence that the consumption of marine based n-3 PUFA is not only extremely useful to treat dyslipidemia, but is also beneficial for otherwise healthy populations in the prevention of hyperlipidaemia and may subsequently reduce the risk of developing CVD.

Acknowledgements

Research funding for DWLM is provided by the Vegetable Oil Industry of Canada and the Manitoba Rural Adaptation Council - Canadian Agricultural Adaptation Program.

Abbreviations

- PUFA

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- TG

Triacylglycerol

- LDL-c

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-c

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- Total-c

Total cholesterol

- FO

Fish oil

- ALA

Alpha-linolenic acid

- EPA

Eicosapentaenoic acid

- DPA

Docosapentaenoic acid

- DHA

Docosahexaenoic acid

- LA

Linoleic acid

- AA

Arachidonic acid

- GLA

Gamma-linolenic acid

- AHA

American Heart Association

- EFSA

European Food Safety Authority

- FSANZ

Food Safety – Australia and New Zealand

Footnotes

Michael A. Leslie and Daniel J. A. Cohen contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

DWLM is a scientific advisor to Vegetable Oil Industry of Canada. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ML, DC and DL conducted the retrieval and analysis of studies. ML and DC drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the determination of inclusion/exclusion criteria and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Michael A. Leslie, Email: mleslie@uoguelph.ca

Daniel J. A. Cohen, Email: cohen@uoguelph.ca

Danyelle M. Liddle, Email: dliddle@uoguelph.ca

Lindsay E. Robinson, Email: lrobinso@uoguelph.ca

David W. L. Ma, Phone: 519-824-4120, Email: davidma@uoguelph.ca

References

- 1.Belanger M, Poirier M, Jbilou J, Scarborough P. Modelling the impact of compliance with dietary recommendations on cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality in Canada. Public Health. 2014;128:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hokanson JE, Austin MA. Plasma triglyceride level is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease independent of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level: a meta-analysis of population-based prospective studies. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1996;3:213–219. doi: 10.1097/00043798-199604000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assmann G, Schulte H, Cullen P. New and classical risk factors–the Munster heart study (PROCAM) Eur J Med Res. 1997;2:237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeppesen J, Hein HO, Suadicani P, Gyntelberg F. Triglyceride concentration and ischemic heart disease: an eight-year follow-up in the Copenhagen Male Study. Circulation. 1998;97:1029–1036. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.97.11.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tirosh A, Rudich A, Shochat T, Tekes-Manova D, Israeli E, Henkin Y, et al. Changes in triglyceride levels and risk for coronary heart disease in young men. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:377–385. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Zeng FF, Liu ZM, Zhang CX, Ling WH, Chen YM. Effects of blood triglycerides on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 61 prospective studies. Lipids Health Dis. 2013;12:159. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-12-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austin MA. Plasma triglyceride as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 1998;14(Suppl B):14B–17B. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacLean DR, Petrasovits A, Connelly PW, Joffres M, O'Connor B, Little JA. Plasma lipids and lipoprotein reference values, and the prevalence of dyslipoproteinemia in Canadian adults. Canadian Heart Health Surveys Research Group. Can J Cardiol. 1999;15:434–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joffres M, Shields M, Tremblay MS, Connor GS. Dyslipidemia prevalence, treatment, control, and awareness in the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Can J Public Health. 2013;104:e252–e257. doi: 10.17269/cjph.104.3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trumbo P, Schlicker S, Yates AA, Poos M. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1621–1630. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(02)90346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products NaAN Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to EPA, DHA, DPA and maintenance of normal blood pressure (ID 502), maintenance of normal HDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 515), maintenance of normal (fasting) blood concentrations of triglycerides (ID 517), maintenance of normal LDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 528, 698) and maintenance of joints (ID 503, 505, 507, 511, 518, 524, 526, 535, 537) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J. 2009;7:1263–1289. [Google Scholar]

- 13.EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products NaAN Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) and maintenance of normal cardiac function (ID 504, 506, 516, 527, 538, 703, 1128, 1317, 1324, 1325), maintenance of normal blood glucose concentrations (ID 566), maintenance of normal blood pressure (ID 506, 516, 703, 1317, 1324), maintenance of normal blood HDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 506), maintenance of normal (fasting) blood concentrations of triglycerides (ID 506, 527, 538, 1317, 1324, 1325), maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 527, 538, 1317, 1325, 4689), protection of the skin from photo-oxidative (UV-induced) damage (ID 530), improved absorption of EPA and DHA (ID 522, 523), contribution to the normal function of the immune system by decreasing the levels of eicosanoids, arachidonic acid-derived mediators and pro-inflammatory cytokines (ID 520, 2914), and “immunomodulating agent” (4690) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061. EFSA J. 2010;8:1796–1828. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, Bittner V, Criqui MH, Ginsberg HN, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:2292–2333. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howe, P, Mori, T, and Buckley, J. Long chain Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease - FSANZ consideration of a commissioned review. FSANZ. 2013. PDF: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/labelling/nutrition/documents/FSANZ%20consideration%20of%20omega-3%20review1.pdf.

- 16.Hooper L, Summerbell CD, Thompson R, Sills D, Roberts FG, Moore HJ, et al. Reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD002137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002137.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris WS. Fish oils and plasma lipid and lipoprotein metabolism in humans: a critical review. J Lipid Res. 1989;30:785–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skulas-Ray AC, West SG, Davidson MH, Kris-Etherton PM. Omega-3 fatty acid concentrates in the treatment of moderate hypertriglyceridemia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:1237–1248. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.7.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris WS. n-3 fatty acids and serum lipoproteins: human studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:1645S–1654S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.5.1645S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei MY, Jacobson TA. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid versus docosahexaenoic acid on serum lipids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2011;13:474–483. doi: 10.1007/s11883-011-0210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein AM, Ding EL, Willett WC, Rimm EB. A meta-analysis shows that docosahexaenoic acid from algal oil reduces serum triglycerides and increases HDL-cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol in persons without coronary heart disease. J Nutr. 2012;142:99–104. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.148973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eslick GD, Howe PR, Smith C, Priest R, Bensoussan A. Benefits of fish oil supplementation in hyperlipidemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2009;136:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balk EM, Lichtenstein AH, Chung M, Kupelnick B, Chew P, Lau J. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on serum markers of cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mori TA, Woodman RJ. The independent effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on cardiovascular risk factors in humans. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:95–104. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000214566.67439.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, Carnethon M, Daniels S, Franch HA, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation. 2006;114:82–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Health Canada . Guidance Document for Preparing a Submission for Food Health Claims. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dyerberg J, Christensen JH, Eskesen D, Astrup A, Stender S. Trans, and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vascular function-a yin yang situation? Atheroscler Suppl. 2006;7:33–35. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodin S, Cunnane SC, Masse B, Lemay A, Jacques H, Asselin G, et al. Flaxseed on cardiovascular disease markers in healthy menopausal women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition. 2008;24:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyerberg J, Eskesen DC, Andersen PW, Astrup A, Buemann B, Christensen JH, et al. Effects of trans- and n-3 unsaturated fatty acids on cardiovascular risk markers in healthy males. An 8 weeks dietary intervention study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:1062–1070. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dodin S, Lemay A, Jacques H, Legare F, Forest JC, Masse B. The effects of flaxseed dietary supplement on lipid profile, bone mineral density, and symptoms in menopausal women: a randomized, double-blind, wheat germ placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1390–1397. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lara JJ, Economou M, Wallace AM, Rumley A, Lowe G, Slater C, et al. Benefits of salmon eating on traditional and novel vascular risk factors in young, non-obese healthy subjects. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hallund J, Madsen BO, Bugel SH, Jacobsen C, Jakobsen J, Krarup H, et al. The effect of farmed trout on cardiovascular risk markers in healthy men. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:1528–1536. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510002527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ambring A, Friberg P, Axelsen M, Laffrenzen M, Taskinen MR, Basu S, et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-inspired diet on blood lipids, vascular function and oxidative stress in healthy subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;106:519–525. doi: 10.1042/CS20030315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navas-Carretero S, Perez-Granados AM, Schoppen S, Vaquero MP. An oily fish diet increases insulin sensitivity compared to a red meat diet in young iron-deficient women. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:546–553. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509220794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baro L, Fonolla J, Pena JL, Martinez-Ferez A, Lucena A, Jimenez J, et al. n-3 Fatty acids plus oleic acid and vitamin supplemented milk consumption reduces total and LDL cholesterol, homocysteine and levels of endothelial adhesion molecules in healthy humans. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:175–182. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2002.0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia-Alonso FJ, Jorge-Vidal V, Ros G, Periago MJ. Effect of consumption of tomato juice enriched with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on the lipid profile, antioxidant biomarker status, and cardiovascular disease risk in healthy women. Eur J Nutr. 2012;51:415–424. doi: 10.1007/s00394-011-0225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamazaki K, Itomura M, Huan M, Nishizawa H, Watanabe S, Hamazaki T, et al. n-3 long-chain FA decrease serum levels of TG and remnant-like particle-cholesterol in humans. Lipids. 2003;38:353–358. doi: 10.1007/s11745-003-1069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coates AM, Sioutis S, Buckley JD, Howe PR. Regular consumption of n-3 fatty acid-enriched pork modifies cardiovascular risk factors. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:592–597. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508025063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stuglin C, Prasad K. Effect of flaxseed consumption on blood pressure, serum lipids, hemopoietic system and liver and kidney enzymes in healthy humans. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2005;10:23–27. doi: 10.1177/107424840501000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patenaude A, Rodriguez-Leyva D, Edel AL, Dibrov E, Dupasquier CM, Austria JA, et al. Bioavailability of alpha-linolenic acid from flaxseed diets as a function of the age of the subject. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:1123–1129. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minihane AM, Brady LM, Lovegrove SS, Lesauvage SV, Williams CM, Lovegrove JA. Lack of effect of dietary n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio on plasma lipids and markers of insulin responses in Indian Asians living in the UK. Eur J Nutr. 2005;44:26–32. doi: 10.1007/s00394-004-0488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sofi F, Giorgi G, Cesari F, Gori AM, Mannini L, Parisi G, et al. The atherosclerotic risk profile is affected differently by fish flesh with a similar EPA and DHA content but different n-6/n-3 ratio. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2013;22:32–40. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fakhrzadeh H, Ghaderpanahi M, Sharifi F, Mirarefin M, Badamchizade Z, Kamrani AA, et al. The effects of low dose n-3 fatty acids on serum lipid profiles and insulin resistance of the elderly: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2010;80:107–116. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831/a000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanders TA, Hall WL, Maniou Z, Lewis F, Seed PT, Chowienczyk PJ. Effect of low doses of long-chain n-3 PUFAs on endothelial function and arterial stiffness: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:973–980. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.018036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hlais S, El-Bistami D, El RB, Mattar MA, Obeid OA. Combined fish oil and high oleic sunflower oil supplements neutralize their individual effects on the lipid profile of healthy men. Lipids. 2013;48:853–861. doi: 10.1007/s11745-013-3819-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nilsson A, Radeborg K, Salo I, Bjorck I. Effects of supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on cognitive performance and cardiometabolic risk markers in healthy 51 to 72 years old subjects: a randomized controlled cross-over study. Nutr J. 2012;11:99. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rizza S, Tesauro M, Cardillo C, Galli A, Iantorno M, Gigli F, et al. Fish oil supplementation improves endothelial function in normoglycemic offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206:569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lovegrove JA, Lovegrove SS, Lesauvage SV, Brady LM, Saini N, Minihane AM, et al. Moderate fish-oil supplementation reverses low-platelet, long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid status and reduces plasma triacylglycerol concentrations in British Indo-Asians. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:974–982. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ciubotaru I, Lee YS, Wander RC. Dietary fish oil decreases C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and triacylglycerol to HDL-cholesterol ratio in postmenopausal women on HRT. J Nutr Biochem. 2003;14:513–521. doi: 10.1016/S0955-2863(03)00101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Offman E, Marenco T, Ferber S, Johnson J, Kling D, Curcio D, et al. Steady-state bioavailability of prescription omega-3 on a low-fat diet is significantly improved with a free fatty acid formulation compared with an ethyl ester formulation: the ECLIPSE II study. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:563–573. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S50464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laidlaw M, Holub BJ. Effects of supplementation with fish oil-derived n-3 fatty acids and gamma-linolenic acid on circulating plasma lipids and fatty acid profiles in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:37–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mann NJ, O'Connell SL, Baldwin KM, Singh I, Meyer BJ. Effects of seal oil and tuna-fish oil on platelet parameters and plasma lipid levels in healthy subjects. Lipids. 2010;45:669–681. doi: 10.1007/s11745-010-3450-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vanschoonbeek K, Feijge MA, Paquay M, Rosing J, Saris W, Kluft C, et al. Variable hypocoagulant effect of fish oil intake in humans: modulation of fibrinogen level and thrombin generation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1734–1740. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000137119.28893.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Stasi D, Bernasconi R, Marchioli R, Marfisi RM, Rossi G, Tognoni G, et al. Early modifications of fatty acid composition in plasma phospholipids, platelets and mononucleates of healthy volunteers after low doses of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60:183–190. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0758-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stark KD, Park EJ, Maines VA, Holub BJ. Effect of a fish-oil concentrate on serum lipids in postmenopausal women receiving and not receiving hormone replacement therapy in a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:389–394. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.2.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Damsgaard CT, Frokiaer H, Andersen AD, Lauritzen L. Fish oil in combination with high or low intakes of linoleic acid lowers plasma triacylglycerols but does not affect other cardiovascular risk markers in healthy men. J Nutr. 2008;138:1061–1066. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brady LM, Lovegrove SS, Lesauvage SV, Gower BA, Minihane AM, Williams CM, et al. Increased n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids do not attenuate the effects of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on insulin sensitivity or triacylglycerol reduction in Indian Asians. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:983–991. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaul N, Kreml R, Austria JA, Richard MN, Edel AL, Dibrov E, et al. A comparison of fish oil, flaxseed oil and hempseed oil supplementation on selected parameters of cardiovascular health in healthy volunteers. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:51–58. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buckley R, Shewring B, Turner R, Yaqoob P, Minihane AM. Circulating triacylglycerol and apoE levels in response to EPA and docosahexaenoic acid supplementation in adult human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:477–483. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanders TA, Gleason K, Griffin B, Miller GJ. Influence of an algal triacylglycerol containing docosahexaenoic acid (22: 6n-3) and docosapentaenoic acid (22: 5n-6) on cardiovascular risk factors in healthy men and women. Br J Nutr. 2006;95:525–531. doi: 10.1079/BJN20051658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stark KD, Holub BJ. Differential eicosapentaenoic acid elevations and altered cardiovascular disease risk factor responses after supplementation with docosahexaenoic acid in postmenopausal women receiving and not receiving hormone replacement therapy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:765–773. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu WH, Lu SC, Wang TF, Jou HJ, Wang TA. Effects of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation on blood lipids, estrogen metabolism, and in vivo oxidative stress in postmenopausal vegetarian women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:386–392. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Geppert J, Kraft V, Demmelmair H, Koletzko B. Microalgal docosahexaenoic acid decreases plasma triacylglycerol in normolipidaemic vegetarians: a randomised trial. Br J Nutr. 2006;95:779–786. doi: 10.1079/BJN20051720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cazzola R, Russo-Volpe S, Miles EA, Rees D, Banerjee T, Roynette CE, et al. Age- and dose-dependent effects of an eicosapentaenoic acid-rich oil on cardiovascular risk factors in healthy male subjects. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]