Abstract

India has a population of 1.21 billion people and there is a high degree of socio-cultural, linguistic, and demographic heterogeneity. There is a limited number of health care professionals, especially doctors, per head of population. The National Rural Health Mission has decided to mainstream the Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy (AYUSH) system of indigenous medicine to help meet the challenge of this shortage of health care professionals and to strengthen the delivery system of the health care service. Multiple interventions have been implemented to ensure a systematic merger; however, the anticipated results have not been achieved as a result of multiple challenges and barriers. To ensure the accessibility and availability of health care services to all, policy-makers need to implement strategies to facilitate the mainstreaming of the AYUSH system and to support this system with stringent monitoring mechanisms.

Keywords: Ayurvedic medicine, homeopathy, indigenous medicine, India, public health

1. Introduction

India has a population of 1.21 billion people and has a wide diversity in terms of socio-cultural, linguistic, and demographic variables.1 In addition, as a middle-income nation, the Indian population has been exposed to a range of communicable diseases, lifestyle disorders, nutritional issues, and medical care problems.2 The incidence/prevalence of diseases, their resulting complications, and their impact on the quality of life of patients and family members can be minimized to a significant extent if quality-assured health care services are accessible to everyone.2,3 In addition, India does not meet the recommended standards/norms for the number of health care professionals per head of population, especially doctors.4,5

2. The Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy system

In India, other than allopathic medicine, different forms of scientifically appropriate and acceptable systems of indigenous medicine, such as the Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy (AYUSH) system, are practiced in different parts of the nation.2,5 The National Rural Health Mission has decided to mainstream the AYUSH system of indigenous medicine to help meet the challenge of the shortage of health care professionals and to strengthen the health care service delivery system.3,6,7

3. Strategies for ensuring mainstreaming of the AYUSH system

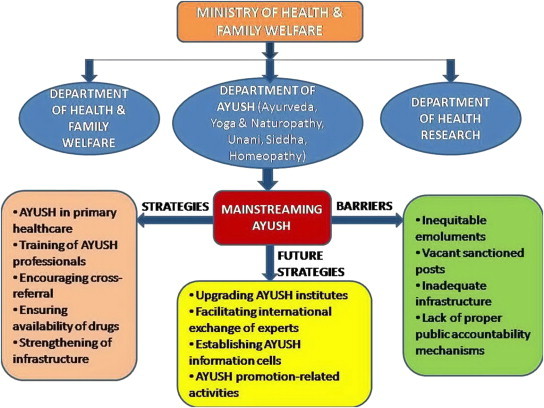

Mainstreaming of the AYUSH system is one of the key strategies under the National Rural Health Mission, under which it is envisaged that all primary health centers, block primary health centers, and community health centers will provide AYUSH treatment facilities under the same roof (Fig. 1).8 The staff required for the AYUSH system are arranged either by the relocation of AYUSH doctors from existing dispensaries or from contractual hiring; these staff are then trained in the primary health care and national health programs.6,8 In addition, other measures have been proposed and implemented with varying range of success,6,8–10 such as: mobilizing existing AYUSH establishments; motivating AYUSH practitioners to spread awareness about their branch of medicine; fostering partnerships with multiple stakeholders; strengthening the existing infrastructure; promoting cross-referral between different streams of medicine; integrating AYUSH with different cadres of outreach workers such as accredited social health activists; implementing special initiatives for the development of AYUSH drugs (e.g., ensuring the ready availability of AYUSH drugs at all levels; strengthening quality control mechanisms to avoid both the manufacture and sale of counterfeit drugs; streamlining the method of drug standardization to ascertain the potency of the drug; building herbariums and crude drug museums; directing state governments to decide which system of medicine should be set up in their respective states; establishing higher centers in district hospitals and medical colleges, such as yoga centers; promoting research work by exploring the local health traditions; expanding the existing legal framework to supervise the manufacture and sale of Ayurveda, Siddha, Unani, and homoeopathic drugs; and making way for an administrative officer to facilitate the effective monitoring and supervision of different activities.

Fig. 1.

Integration of departments of AYUSH and Health & Family Welfare.

4. Experience gained

Multiple interventions have been implemented to ensure a systematic merger; nevertheless, the anticipated results have not been achieved. This indirectly indicates the presence of multiple challenges and barriers, for example: variability in the basic philosophy of practice; disparities in the approach to specific clinical conditions or in decision-making; the lack of specific guidelines to promote cross-referral; unfilled positions; inequitable compensation; minimal support in terms of logistics and infrastructure; an unexpected rise in cross-practice; ethical issues (such as unfriendly relationships between practitioners of either system); and the absence of public accountability mechanisms at the primary care level. These challenges undermine the value of AYUSH, demotivate both practitioners and patients, and hence fail to provide the intended support to the public health system.8,10–14

5. Future strategies and innovations

To bridge the gap in demand for public health professionals in India, the plan is to step up further activities to ensure the mainstreaming of AYUSH by: establishing and strengthening AYUSH institutes and colleges; organizing training programs for personnel from the AYUSH sector; formulating standardized guidelines for the treatment of different conditions; encouraging the exchange of experts and officers at an international level; extending monetary support to drug manufacturers and AYUSH institutions for international propagation of their stream; developing AYUSH information outlets in multiple nations; conducting fellowship courses under different streams of AYUSH in India for students from different countries; promoting community-based research to assess the scope of AYUSH; building links with pharmacists and their associations; and by ensuring customized implementation of strategies that have been successfully employed in other countries.9,10,15,16

6. Conclusion

To ensure the accessibility and availability of health care services to all, policy-makers have to implement strategies to facilitate the mainstreaming of AYUSH, supported by stringent monitoring mechanisms.

Conflicts of interest

All contributing authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Center for Food and Biomolecules, National Taiwan University.

References

- 1.Ministry of Home Affairs, India . Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner; New Delhi: 2011. Census of India 2011.http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/PCA/PCA_Highlights/pca_highlights_file/India/4Executive_Summary.pdf Available from: Accessed 22.03.14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shrivastava S.R., Shrivastava P.S., Ramasamy J. Implementation of public health practices in tribal populations of India – challenges & remedies. Healthcare Low-resource Settings. 2013;1:e3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS) Guidelines for Primary Health Centers. 2012. http://health.bih.nic.in/Docs/Guidelines/Guidelines-PHC-2012.pdf Available from: Accessed 19.02.14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Statistics Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare . 2012. Rural Health Statistics in India in 2012.http://nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/publication/RHS-2012.pdf Available from: Accessed 22.03.14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park K. Health care of the community. In: Park K., editor. Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. 20th ed. Banarsidas Bhanot; Jabalpur: 2009. pp. 800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of AYUSH, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Mainstreaming of AYUSH under National Rural Health Mission – Operational Guidelines 2011. Available from: http://indianmedicine.nic.in/writereaddata/mainlinkFile/File614.pdf. Accessed 19.02.14.

- 7.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Rural Health Mission – Meeting People's Health Needs in Rural Areas: Framework for Implementation, 2005–2012. Available from: http://nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/about-nrhm/nrhm-framework-implementation/nrhm-framework-latest.pdf. Accessed 04.07.14.

- 8.Gopichandran V., Satish Kumar Ch. Mainstreaming AYUSH: an ethical analysis. Indian J Med Ethics. 2012;9:272–277. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2012.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar D., Raina S.K., Bhardwaj A.K., Chander V. Capacity building of AYUSH practitioners to study the feasibility of their involvement in non-communicable disease prevention and control. Anc Sci Life. 2012;32:116–119. doi: 10.4103/0257-7941.118552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandra S. Status of Indian medicine and folk healing: with a focus on integration of AYUSH medical systems in healthcare delivery. Ayu. 2012;33:461–465. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.110504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandra S. Department of AYUSH, Government of India; New Delhi: 2011. Status of Indian medicine and folk healing. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutatkar R.K. Status of Indian medicine and folk healing: part II. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2013;4:184–186. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakshmi J.K. Less equal than others? Experiences of AYUSH medical officers in primary health centres in Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Med Ethics. 2012;9:18–21. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2012.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madhu R. Practices at an AYUSH health camp for asthma in Pendra, Chhattisgarh. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2011;2:170–173. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.90765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh R.H. Perspectives in innovation in the AYUSH sector. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2011;2:52–54. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.82516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Report of working group on AYUSH for 12th five-year plan (2012–17). Available from: http://planningcommission.nic.in/aboutus/committee/wrkgrp12/health/WG_7_ayush.pdf. Accessed 04.07.14.