Abstract

Introduction

Nephropatia epidemica (NE), a relatively mild form of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome caused by the Puumala virus (PUUV), is endemic in northern Sweden. We aim to study the risk factors associated with NE in this region.

Methods

We conducted a matched case–control study between June 2011 and July 2012. We compared confirmed NE cases with randomly selected controls, matched by age, sex, and place of infection or residence. We analyzed the association between NE and several occupational, environmental, and behavioral exposures using conditional logistic regression.

Results

We included in the final analysis 114 cases and 300 controls, forming 246 case–control pairs. Living in a house with an open space beneath, making house repairs, living less than 50 m from the forest, seeing rodents, and smoking were significantly associated with NE.

Conclusion

Our results could orient public health policies targeting these risk factors and subsequently reduce the NE burden in the region.

Keywords: Puumala virus, risk factors, Sweden

Hantaviruses are rodent-borne, enveloped RNA viruses of the family Bunyaviridae, and each hantavirus is carried by a specific rodent, chronically infected. When transmitted to humans, Old World hantaviruses cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) while New World hantaviruses cause hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) (1).

Nephropatia epidemica (NE) is a relatively mild form of HFRS, caused by Puumala virus (PUUV), a hantavirus carried naturally and shed by the bank vole (Myodes glareolus) (2). Transmission of the virus to humans occurs mainly through the inhalation of infectious aerosols generated from saliva, urine, and/or feces of the bank vole (3). The incubation period varies between 2 and 6 weeks. Typical symptoms of NE include headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, back pain, and signs of renal failure. Ophthalmological and neurological disturbances might also occur in acute NE (4). While 80% of the infections are asymptomatic, some patients may suffer long-term sequelae, such as hypertension or impaired hypophyseal function. Up to 5% of the infected patients may develop severe disease requiring hospitalization and hemodialysis (5). The NE diagnosis is based on detection of IgM antibodies to PUUV. After the infection antibodies arise within 6 days of illness (6). Infection is thought to leave life-long protection (5).

PUUV and NE are very common in Finland, northern Sweden, Estonia, the Ardennes forest region (Belgium and France), parts of Germany, Slovenia, and parts of European Russia (7). Local geographical and meteorological factors influence the bank voles’ dynamics and NE epidemiology leading to large yearly variations in the number of cases (5, 8). Although environmental factors influence the bank vole population dynamics and behavior, risk factors for hantaviral disease transmission to humans also depend on human proximity, behavior, and land-use patterns. Previously described risk factors for PUUV infection in Europe are: having seen small rodents, cleaning utility rooms or visiting forest shelters, spending time in forests, living in a home less than 100 m from the forest, handling firewood, and smoking (1, 9–11).

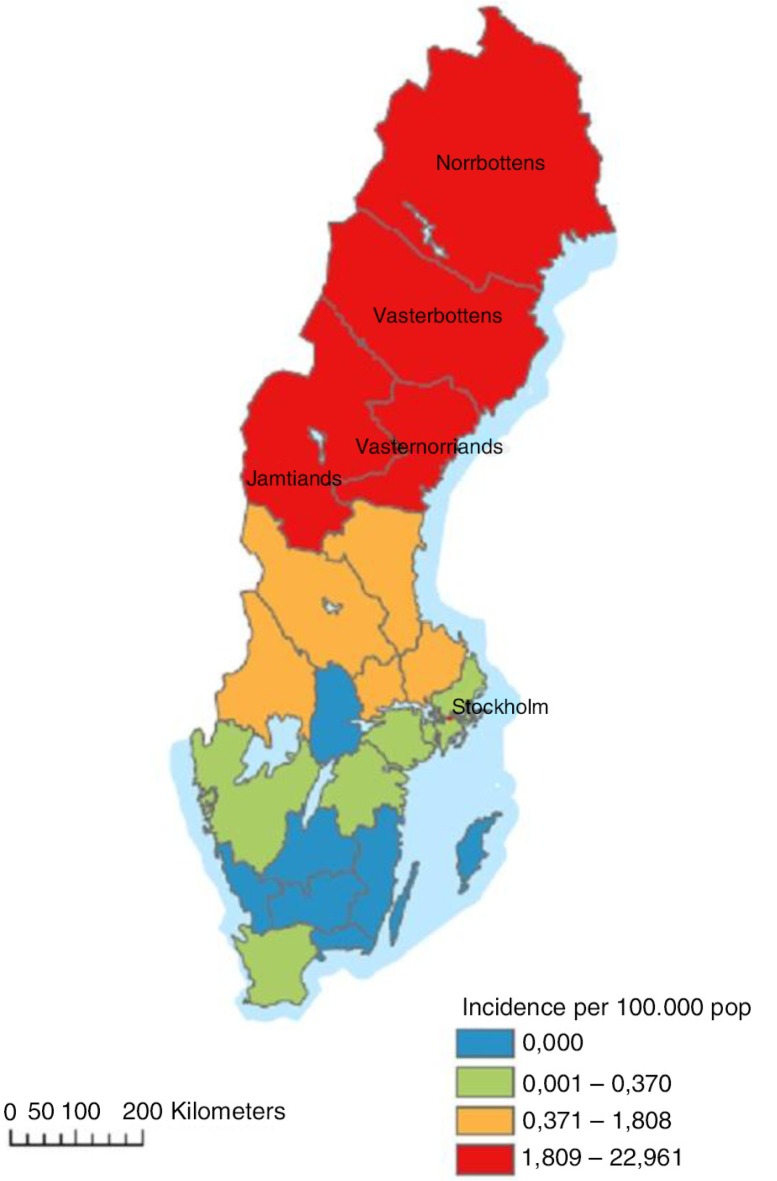

Until now, PUUV is the only hantavirus known to occur endemically in Sweden (12). NE is a mandatory notifiable disease, cases being reported in the national electronic surveillance system at the Swedish Institute for Communicable Disease Control (SMI). Each case is notified through a clinical and a laboratory report linked by a unique identifier. Approximately 90% of all NE cases in Sweden are reported from the four northernmost counties: Västerbotten, Norrbotten, Västernorrland, and Jämtland, a region hereafter referred to as northern Sweden (Fig. 1). In this area, NE is the most prevailing serious febrile viral infection among adults, second only to influenza (13). At the national level, the annual reported number of cases in the last decade varied between 48 (2012) and 2,193 (2007), giving an incidence of 0.50–23.92 cases/100,000 (14). During the most recent NE outbreak in 2007, 1,964 out of 2,193 cases (89.5%) were registered in the northern region.

Fig. 1.

The NE incidence in Sweden in the study period (June 2011–July 2012).

A study performed in 1994 indicated an NE seroprevalence of 5.4% in Norrbotten and Västerbotten. The same study revealed that approximately one in eight PUUV infected individuals developed a disease severe enough to seek medical attention (15). To date, only limited knowledge is available regarding individual risk factors for acquiring NE in Sweden and about the effect of using preventive measures. The current recommendations which have been advocated for several years and advertised in local media by the county medical offices (CMOs) in the four counties in the months preceding the study were: avoid direct contact with bank voles, use gloves when cleaning or touching areas where rodents may have been, cleaning with wet rather than dry methods to avoid raising dust, rake grass only after rain, and use facial mask when being exposed to risk of transmission (16–18).

We aimed to identify specific risk factors in order to guide public health policy towards actions targeted on reducing NE incidence and disease burden in affected counties. We also aimed to investigate if recommended protective measures prevent an individual from becoming infected.

Methods

We performed a matched case–control study between July 2011 and June 2012. The study period was chosen in order to follow cases registered during an entire year. We used the following case definition: any person 16 years or older, living in northern Sweden, diagnosed and notified to SMI as laboratory-confirmed acute NE (positive test for IgM anti-PUUV), and without a history of traveling abroad 6 weeks prior to onset of symptoms. We used a web-based population registry to randomly select six controls for each case, matched by sex, age (± 5 years), and the same five-digit postal code as the stated place of infection. When the place of infection was unknown, controls were selected from the same postal code as the residence address of the case. Lists with cases and controls were prepared by SMI and sent to the regional CMOs on a monthly basis for them to contact the cases and controls and send the material described below.

Postal standardized questionnaires asking about exposure to specific risk factors for NE and potential preventive measures were sent together with an invitation letter to participate in the study. The questionnaire enquired about possible exposures 6 weeks prior to the symptom onset for cases and 6 weeks prior to receiving the questionnaire for controls. In the questionnaire, we also included enquiries about occupational or recreational exposures, type of residence, distance between residential house and forest, contact with rodents or rodent droppings, as well as cleaning summer houses or annexes. As a potential preventive measure, we investigated cases and controls about the use of respiratory protection, washing hands, and wearing gloves while performing various activities considered as a risk for acquiring NE.

We calculated matched odds-ratio (mOR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) using conditional logistic regression. A priori selected possible confounders, statistically significant variables and variables with p values less than 0.2 in the bivariable analysis were included in the multivariable conditional logistic regression model in order to estimate the adjusted odds-ratio (aOR). All analyses were performed using STATA 12 (Stata Corp USA).

In order to minimize the misclassification of controls due to asymptomatic disease, we also sent them an invitation to test for the presence of antibodies anti-PUUV. Blood samples were collected by the local or regional laboratories and sent to the SMI laboratory. Detection of hantavirus-specific IgM and IgG antibodies tests was performed using either native antigen or a recombinant antigen produced in the baculovirus expression system: bac-PUUV-N based on PUUV, strain Sotkamo (19). Acute-phase serum samples were analyzed for PUUV-specific IgM using µ-capture ELISAs as described earlier (20). Goat anti-human IgM serum (Cappel), diluted in coating buffer (0.05 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.6) was incubated to microtiter plates over night at room temperature. Patient and control sera diluted 1:200 in ELISA buffer (PBS with 0.05% BSA and 0.05% Tween-20) were incubated in duplicate wells. PUUV baculovirus-expressed N antigen was added, subsequently followed by the hantavirus cross-reactive anti-PUUV bank vole Mab 1C12 (21), conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). All incubations (100 µl in each well) were performed for 1 h at 37°C and plates were washed five times between each step. Specific antibody binding was detected by TMB substrate. The cut-off value for positive samples was set at optical density (OD) of 0.150450.

Hantavirus IgG ELISA based on Mab-captured native PUUV N antigen was performed essentially as described previously (22). Briefly, microtiter plates were coated with the hantavirus N-reactive Mab 1C12 (21) at 4 µg/ml, and incubated overnight at 4°C. All subsequent incubations were for 1 h at 37°C and plates were washed five times between each step. After blocking of unsaturated binding sites with 3% BSA in PBS, viral antigens were added, followed by serum samples (diluted 1:400) in duplicate wells in both antigen-sensitized and control wells. Goat anti-human IgG (γ-chain specific) alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was added. Hantavirus-specific IgG was detected by Sigma 104® phosphatase substrate and ODs were measured at 405 nm after 30 min incubation at 37°C. All absorbances were adjusted according to a late convalescent standard control positive serum, for which the mean OD value of duplicate wells was set to 1.000. Background ODs for the control wells were reduced from the OD in wells incubated with the viral antigen. The cut-off value for positive samples was set at OD=0.100.

The study was approved by the Swedish ethical committee in June 2011 (number Dnr2011/819-31/3).

Results

Between July 2011 and March 2012, a total of 171 NE cases from northern Sweden were reported to SMI (14). The disease incidence for the study period is presented in Fig. 1. Five cases were excluded from the study for being younger than 16. We invited 166 cases and 996 randomly chosen controls to participate in the study.

A total of 123 cases (74% response rate) and 379 controls (38% response rate) sent back the questionnaires. Overall 197/379 (52%) controls provided a blood sample for testing for the presence of IgG antibodies anti-PUUV; 46/197 (23%) were excluded from further analysis for being either positive (34/46) or inconclusive (12/46). Of the 34 controls positive for IgG anti-PUUV (17.3% seroprevalence among tested controls), 68% were female and the median age was 64 (range 41–79). The distribution of the positive controls was almost uniform: nine in both Jämtland and Västernorrland and eight in Norrbotten and Västerbotten respectively. Furthermore, 33 controls and nine cases were excluded due to a history of traveling abroad. In the final analysis we included 114 cases and 300 controls.

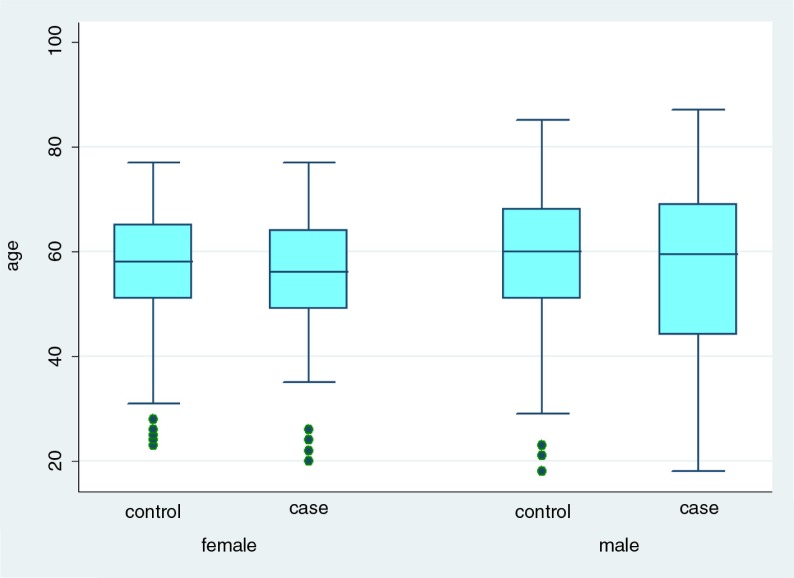

Overall, 62/114 cases (54%) and 162/300 controls (54%) were males. The median age for cases was 56 years (range 18–87) and 58 years (range 18–85) for controls (Fig. 2). Most of the cases included in the study were reported from Västerbotten and Norrbotten: 49/114 (43%) and 30/114 (30%), respectively. The geographical distribution of controls replying to the questionnaire was similar, with higher percentages for the two aforementioned counties; however, no differences were found between the four regions regarding the proportion of cases and controls included in the study (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Age and sex distribution of cases and controls, NE study, Sweden 2011–2012.

Table 1.

Distribution of cases and controls by reporting county, NE study, Sweden 2011–2012

| Västerbotten | Norrbotten | Västernorrland | Jämtland | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases reported in SmiNet | 59 | 50 | 34 | 28 | 171 |

| Cases included in analysis | 49 | 30 | 20 | 15 | 114 |

| Controls included in analysis | 124 | 79 | 47 | 50 | 300 |

Regarding the disease severity, 62/114 (54%) cases included in the study were hospitalized, with 5 days median hospitalization time (range 1–15).

For the statistical analysis, 246 case–control pairs were available. The case–control ratio varied from 1:1 to 1:6. In the bivariable analysis, we identified occupational risk factors like mowing the lawn, pulling weeds, and making house repairs as significantly associated with NE (Table 2). We also found the following as environmental risk factors: living in a wooden summer house, living less than 50 m from a forest and living in a house with an open space beneath. In terms of rodent presence in human proximity we found that noticing rodents and noticing rodent droppings was significantly associated with the disease. Also, cleaning rodent droppings appeared to be associated with NE. Other risk factors for NE were visiting a summer house, vacuuming and dry-sweeping a summer house, and using a chainsaw. We also identified several risk factors that appeared to be protective: living in a house made of bricks or stone, living in a house with a concrete foundation and having knowledge of NE.

Table 2.

Matched odds-ratios (mOR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and p value through conditional logistic regression for various exposures, Sweden 2011–2012

| Cases | Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Exposure | n/N | (%) | n/N | % | mOR (95% CI) | p |

| Occupational risk factors | ||||||

| Mowing the lawn | 43/106 | 41 | 57/267 | 21 | 5 (2.3–11) | <0.001 |

| Vacuuming a summer house | 24/69 | 35 | 21/190 | 11 | 4.7 (1.8–12) | 0.001 |

| Making house repairs | 20/110 | 18 | 21/296 | 7 | 3.6 (1.5–8.6) | 0.003 |

| Visiting a summer house | 51/113 | 45 | 94/299 | 31 | 2.2 (1.2–3.8) | 0.004 |

| Pulling weeds | 29/106 | 27 | 51/267 | 19 | 2.7 (1.3–5.6) | 0.005 |

| Using a chainsaw | 17/114 | 15 | 18/299 | 6 | 2.7 (1.2–5.8) | 0.012 |

| Dry-sweeping a summer house | 25/62 | 40 | 27/157 | 17 | 3.6 (1.3–9.6) | 0.012 |

| Spending free time in the woods | 89/114 | 78 | 197/298 | 66 | 1.9 (1.03–3.5) | 0.037 |

| Carrying wood | 77/113 | 68 | 177/278 | 59 | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 0.198 |

| Farming | 16/109 | 15 | 26/291 | 9 | 1.6 (0.8–3.5) | 0.203 |

| Working in the woods | 38/111 | 34 | 86/295 | 29 | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) | 0.435 |

| Cutting wood | 38/113 | 32 | 87/299 | 29 | 1.2 (0.6–2) | 0.627 |

| Raking leaves or grass | 26/106 | 25 | 66/267 | 25 | 1.1 (0.6–2) | 0.825 |

| Working with hay | 13/111 | 12 | 22/294 | 7 | 1 (0.4–2.6) | 0.897 |

| Environmental risk factors | ||||||

| Living in a wooden summer house | 28/114 | 25 | 22/300 | 7 | 4.8 (2.2–10.2) | <0.001 |

| Living in a house with open space beneath | 59/102 | 58 | 78/276 | 28 | 4.4 (2.4–8.1) | <0.001 |

| Living in a house with concrete foundationa | 9/102 | 9 | 86/276 | 31 | 0.16 (0.07–0.4) | <0.001 |

| Living less than 50 m from a forest | 75/112 | 67 | 132/293 | 45 | 2.4 (1.4–4.1) | 0.001 |

| Living in a house made of brick or stonea | 4/114 | 4 | 28/300 | 10 | 0.14 (0.03–0.65) | 0.011 |

| Rodent related risk factors | ||||||

| Noticing rodents | 53/114 | 46 | 51/298 | 17 | 6.7 (3.4–13.4) | <0.001 |

| Noticing rodent droppings | 57/114 | 50 | 54/298 | 18 | 7.6 (3.7–15.4) | <0.001 |

| Cleaning rodent droppings | 61/113 | 54 | 90/296 | 30 | 2.8 (1.6–4.8) | 0.000 |

| Using rodent traps | 36/114 | 32 | 63/295 | 21 | 1.6 (0.9–2.9) | 0.093 |

| Using rodent poison | 10/114 | 9 | 21/295 | 7 | 1.2 (0.5–2.8) | 0.750 |

| Other risk factors | ||||||

| Previous knowledge about NEa | 30/35 | 85 | 285/298 | 96 | 0.14 (0.03–0.8) | 0.027 |

| Owning a cat | 27/112 | 24 | 95/299 | 32 | 0.6 (0.8–1.1) | 0.080 |

| Smoking | 24/110 | 22 | 42/296 | 14 | 1.6 (0.8–2.9) | 0.172 |

Variable not included in the multivariable model.

n=cases exposed; N=total cases replying to the question.

In terms of potential preventive measures, only 4/50 (8%) of cases and 2/79 (2%) of controls stated they always used a mask while cleaning rodent droppings, while none of the cases reported always wearing a mask when mowing the lawn, compared to one control out of 55 (2%) (p=0.617). Similar proportions of cases and controls stated always using gloves while mowing the lawn (28% vs. 31%, p=0.322). Overall, fewer cases stated that they always wore gloves while doing house repairs, compared to the controls (40% vs. 53%, p=0.294) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Descriptive data on potential preventive measures, NE case–control study, Sweden 2011–2012

| Always | >50% | <50% | Never | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Potential preventive measure | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls |

| Wearing mask when doing repairs (N=34) | 3/16 (19%) | 1/18 (6%) | 2/16 (12%) | 2/18 (11%) | 1/16 (6%) | 3/18 (17%) | 10/16 (63%) | 12/18 (66%) |

| Wearing mask when cleaning rodent droppings (N=129) | 4/50 (8%) | 2/79 (3%) | 1/50 (2%) | 1/79 (1%) | 4/50 (8%) | 5/79 (6%) | 41/50 (52%) | 71/79 (90%) |

| Wearing mask when mowing the lawn (N=97) | 0/42 (0%) | 1/55 (2%) | 2/42 (5%) | 1/55 (2%) | 1/42 (2%) | 2/55 (4%) | 39/42 (93%) | 51/55 (92%) |

| Wearing gloves when doing repairs (N=32) | 6/15 (40%) | 9/17 (53%) | 6/15 (40%) | 3/17 (18%) | 1/15 (7%) | 2/17 (11%) | 2/15 (13%) | 3/17 (18%) |

| Wearing gloves when cleaning droppings (N=128) | 26/52 (50%) | 35/76 (46%) | 7/52 (13%) | 13/76 (17%) | 10/52 (20%) | 15/76 (20%) | 9/52 (17%) | 13/76 (17%) |

| Wearing gloves when mowing the lawn (N=96) | 7/42 (28%) | 17/54 (31%) | 7/42 (28%) | 9/54 (17%) | 12/42 (28%) | 9/54 (17%) | 16/42 (38%) | 19/54 (35%) |

| Washing hands after doing repairs (N=35) | 8/16 (50%) | 6/19 (31%) | 5/16 (31%) | 3/19 (16%) | 2/16 (13%) | 6/19 (31%) | 1/16 (6%) | 4/19 (22%) |

| Washing hands after cleaning droppings (N=138) | 39/57 (68%) | 45/81 (56%) | 7/57 (12%) | 13/81 (16%) | 8/57 (14%) | 18/81 (22%) | 3/57 (6%) | 5/81 (4%) |

| Washing hands after mowing the lawn (N=97) | 6/43 (14%) | 19/54 (35%) | 11/43 (26%) | 16/54 (29%) | 22/43 (51%) | 14/54 (26%) | 4 (9%) | 15/54 (10%) |

N=number of valid replies from cases and controls.

Variables having a p value lower than 0.2 in the bivariable analysis were included in the multivariable conditional logistic regression model, except for living in a house made of bricks or stone, living in a house with a concrete foundation, and having knowledge of NE, which were excluded because of the low number of exposed cases. The model revealed that cases were 11 times more likely to have been making house repairs during the previous 6 weeks compared to the controls (p=0.014), four times more likely to have lived in a house with open space beneath it (p=0.012), and almost three times more likely to have lived less than 50 m from a forest (p=0.043), compared to controls (Table 4). Regarding the rodent presence in the human proximity, cases were almost seven times more likely to have seen rodents more than 4 days each week compared to controls (p=0.008). In terms of behavioral risk factors, we found that the cases were almost six times more likely to have been smoking compared to controls (p=0.017).

Table 4.

Adjusted mOR with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values, Sweden 2011–2012

| Exposure | Adjusted mOR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Occupational risk factors | ||

| Making house repairs | 11 (1.6–73.9) | 0.014 |

| Mowing the lawn | 3.7 (0.7–20) | 0.121 |

| Visiting a summer house | 1.6 (0.5–5.0) | 0.393 |

| Pulling weeds | 1.9 (0.4–9.8) | 0.441 |

| Spending free time in the woods | 0.7 (0.2–2.2) | 0.578 |

| Using a chainsaw | 1.4 (0.3–5.7) | 0.636 |

| Carrying wood | 0.8 (0.3–2.4) | 0.749 |

| Environmental risk factors | ||

| Living in a house with open space beneath | 4.3 (1.4–13.3) | 0.012 |

| Living less than 50 m from a forest | 2.6 (1.03–6.8) | 0.043 |

| Living in wooden summer house | 1.8 (0.4–9.3) | 0.479 |

| Rodent related risk factors | ||

| Noticing rodents | 6.8 (1.6–28,4) | 0.008 |

| Noticing rodent droppings | 2.4 (0.7–8.4) | 0.152 |

| Handling mice | 0.37 (0.1–2.2) | 0.287 |

| Using rodent traps | 1.4 (0.5–4.1) | 0.514 |

| Cleaning rodent droppings | 0.9 (0.3–2.9) | 0.894 |

| Other risk factors | ||

| Smoking | 5.7 (1.4–23.9) | 0.017 |

| Owning a cat | 0.7 (0.2–2.4) | 0.605 |

Discussions and conclusions

This study provides the first evidence on risk factors for NE in the Swedish setting and describes two previously unidentified risk factors, that is, making house repairs and living in a house with an open space beneath. These risk factors are consistent with the known transmission route of PUUV, as having an open space beneath the house may facilitate for rodents to come in proximity to humans. Also, doing house repairs by tearing down a wall or reaping open the house's floor may facilitate dust carrying virus particles becoming airborne. The study also confirmed previously identified risk factors documented in studies from other countries: living close to the woods (9), seeing rodents frequently, and the presence of rodents in proximity to humans (9, 10).

In addition to identifying new risk factors, and consistent with a previous report, we found that smoking was associated with a higher risk of becoming a case (1). The reason for this has not been investigated, but it seems likely that damage to the respiratory tract caused by smoking makes smokers more vulnerable to infection. Further studies are needed in order to describe the reasons why smoking represents an NE risk factor.

All the risk factors we identified, with the exception of smoking, are directly or indirectly related to bank voles living in proximity to humans. Several traditional risk factors like using rodent traps, noticing rodent droppings, or cleaning rodent droppings were not associated with NE, perhaps due to un-documented protective measures that people might take. Previous studies have documented visiting a forest shelter as a risk factor for NE (10, 23). Although significant in the bivariable analysis, staying or visiting a summer house 6 weeks prior to the onset of disease was not identified as a risk factor in the multivariate model. This could indicate that residents in the investigated counties of Sweden are more likely to be exposed to PUUV in their permanent residence or during other activities, than when visiting or cleaning a summer house. This finding seems to be concordant with the one described in a previous study in Sweden, in a cohort of 862 confirmed NE cases. Among them, 54% stated the year-round residence as possible place of infection, while only 28% stated a holiday house (13). This is likely since bank voles’ population dynamics and behavior have been described in close interaction with highly populated areas in northern Sweden (2).

To the best of our knowledge, no study so far has aimed to identify the individual protective measures against NE. We intended to gather information about behaviors that were believed to be protective and therefore recommended (e.g. wearing a mask during certain activities, washing hands, wearing gloves, or wetting the floor before cleaning closed spaces), but we also tried to identify if other actions could play a role in preventing persons from acquiring NE. In the present study, controls stated in a higher percentage that they were more aware of NE (95%) compared to cases (85%). However, a large percentage of cases did not answer whether they had previous knowledge regarding the disease before onset of their disease. We either could not perform statistical analysis to test the protective role of any preventive measures due to small sample size, or we did not observe any difference between cases and controls in terms of up-taking preventive measures. The small number of people using protective equipment might indicate that the population was not aware of the recommended protective measures despite the aforementioned information campaigns, that their trust in the potential protective effect was limited, or that that they found the advice to be impractical or inconvenient.

When looking only at individual risk factors, living the last 6 weeks in a house with a concrete foundation, or in a house made of stone or bricks, appeared to be protective. We could not test their significance in the multivariable model due to the small sample size; however, one might consider that their protective role could be explained by the lower possibility for rodents to enter the buildings and to come in proximity to humans. This would make sense since having an open space beneath the house was found to be a significant risk factor for getting infected by PUUV.

We found that the seroprevalence of IgG anti-PUUV among the tested controls was 17.3%. Although this finding could be the result of over-matching, it still raises the question about the true prevalence of antibodies anti-PUUV in the general population in northern Sweden. The only previously existing estimate on this seroprevalence (5.4%) was described in an investigation from 1990, showing also that the seroprevalence was higher in older people, farmers, and forestry workers (15).

Our study has some limitations. We aimed to describe the NE risk factors during a whole year, from July 2011 to June 2012. Due to absence of cases, we were forced to terminate the study data collection in March 2012. Recall bias might have been present due to the time delay between the time when a person got infected and received the questionnaire. We cannot exclude the existence of residual confounding due to risk factors that we did not introduce in the model, and this might have influenced our results. Another limitation that might be considered is the low response rate among the controls, although this was partially compensated by the number of controls selected for each case. Moreover, not all of the controls agreed to be tested for the presence of IgG anti-PUUV. Due to a small sample size we had to include controls that had not been tested and therefore we may have included undiagnosed infections in the final analysis. This might have biased our results due to misclassification of cases and may have lessened our chances of finding an association if there was one.

This study has increased our knowledge about risk factors for NE in Sweden. Although the results are limited to conditions in northern Sweden, it is likely that many of the findings have universal importance in affected areas. Unfortunately, the study did not have enough power to provide an evidence base for the recommendations about preventive measures that are given today. As we think that this is important, we would like to encourage more studies on this. In the meantime, we think that the new risk factors identified in this paper should be added to the current information on risk factors and that recommendations on preventive measures should take these into consideration, for example on guidance when building or refurnishing houses. Furthermore, a new seroprevalence study aiming at determining the anti-PUUV prevalence among the general population in affected areas could add important knowledge about the NE transmission, as our study suggests that it may be higher than previously described.

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues at the local public health authorities in the counties Västerbotten, Norbotten, Västernorrland, and Jämtland for their help throughout the whole study period. This study was partially funded by EU grant FP7-261504 EDENext and is cataloged by the EDENext Steering Committee as EDENext000 (www.edenext.eu). The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Vapalahti K, Virtala AM, Vaheri A, Vapalahti O. Case-control study on Puumala virus infection: smoking is a risk factor. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:576–84. doi: 10.1017/S095026880999077X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsson GE, White N, Hjalten J, Ahlm C. Habitat factors associated with bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus) and concomitant hantavirus in northern Sweden. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2005;5:315–23. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2005.5.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viel JF, Lefebvre A, Marianneau P, Joly D, Giraudoux P, Upegui E, et al. Environmental risk factors for haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in a French new epidemic area. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139:867–74. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810002062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hautala T, Hautala N, Mahonen SM, Sironen T, Paakko E, Karttunen A, et al. Young male patients are at elevated risk of developing serious central nervous system complications during acute Puumala hantavirus infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:217. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vapalahti O, Mustonen J, Lundkvist A, Henttonen H, Plyusnin A, Vaheri A. Hantavirus infections in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:653–61. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00774-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makary P, Kanerva M, Ollgren J, Virtanen MJ, Vapalahti O, Lyytikainen O. Disease burden of Puumala virus infections, 1995–2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1484–92. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaheri A, Henttonen H, Voutilainen L, Mustonen J, Sironen T, Vapalahti O. Hantavirus infections in Europe and their impact on public health. Rev Med Virol. 2013;23:35–49. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarz AC, Ranft U, Piechotowski I, Childs JE, Brockmann SO. Risk factors for human infection with Puumala virus, southwestern Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1032–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1507.081413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowcroft NS, Infuso A, Ilef D, Le GB, Desenclos JC, Van LF, et al. Risk factors for human hantavirus infection: Franco–Belgian collaborative case-control study during 1995–6 epidemic. BMJ. 1999;318:1737–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7200.1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winter CH, Brockmann SO, Piechotowski I, Alpers K, an der Heiden M, Koch J, et al. Survey and case-control study during epidemics of Puumala virus infection. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:1479–85. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809002271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van LF, Thomas I, Clement J, Ghoos S, Colson P. A case-control study after a hantavirus infection outbreak in the south of Belgium: who is at risk? Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:834–9. doi: 10.1086/515196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahlm C, Thelin A, Elgh F, Juto P, Stiernstrom EL, Holmberg S, et al. Prevalence of antibodies specific to Puumala virus among farmers in Sweden. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;24:104–8. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsson GE, Dalerum F, Hornfeldt B, Elgh F, Palo TR, Juto P, et al. Human hantavirus infections, Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1395–401. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.030275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Swedish Institute For Comunnicable Disease Control. Nefropatia epidemica statistics; Stockholm: The Swedish Institute For Comunnicable Disease Control; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahlm C, Linderholm M, Juto P, Stegmayr B, Settergren B. Prevalence of serum IgG antibodies to Puumala virus (haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome) in northern Sweden. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;113:129–36. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800051542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamtland County Council. Nefropatia epidemica information. 2013. Available from: http://www.1177.se/Jamtland/Fakta-och-rad/Sjukdomar/Sorkfeber/ [cited 20 March 2012]. (In Swedish)

- 17.Vasternorrland County Council. Nefropatia epidemica information. 2013. Available from: http://www.1177.se/Vasternorrland/Fakta-och-rad/Sjukdomar/Sorkfeber/ [cited 20 March 2012]. (In Swedish)

- 18.Vasterbotten Department of Communicable Disease Control. Vasterbotten County Council; 2013. Nephropatia epidemica information. Available from: http://www.vll.se/Sve/Centralt/Standardsidor/V%c3%a5rdOchH%c3%a4lsa/Smittskydd/Nedladdningsboxar/Filer/Information om sorkfeber rev 2013.pdf. [cited 21 May 2013]. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vapalahti O, Lundkvist A, Kallio-Kokko H, Paukku K, Julkunen I, Lankinen H, et al. Antigenic properties and diagnostic potential of puumala virus nucleocapsid protein expressed in insect cells. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:119–25. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.119-125.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lundkvist A, Hukic M, Horling J, Gilljam M, Nichol S, Niklasson B. Puumala and Dobrava viruses cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Bosnia-Herzegovina: evidence of highly cross-neutralizing antibody responses in early patient sera. J Med Virol. 1997;53:51–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundkvist A, Fatouros A, Niklasson B. Antigenic variation of European haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome virus strains characterized using bank vole monoclonal antibodies. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2097–103. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-9-2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sjolander KB, Elgh F, Kallio-Kokko H, Vapalahti O, Hagglund M, Palmcrantz V, et al. Evaluation of serological methods for diagnosis of Puumala hantavirus infection (nephropathia epidemica) J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3264–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3264-3268.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reusken C, Heyman P. Factors driving hantavirus emergence in Europe. Curr Opin Virol. 2013;3:92–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]