ABSTRACT

The TOR (target of rapamycin [sirolimus]) is a universally conserved kinase that couples nutrient availability to cell growth. TOR complex 1 (TORC1) in Schizosaccharomyces pombe positively regulates growth in response to nitrogen availability while suppressing cellular responses to nitrogen stress. Here we report the identification of the GATA transcription factor Gaf1 as a positive regulator of the nitrogen stress-induced gene isp7+, via three canonical GATA motifs. We show that under nitrogen-rich conditions, TORC1 positively regulates the phosphorylation and cytoplasmic retention of Gaf1 via the PP2A-like phosphatase Ppe1. Under nitrogen stress conditions when TORC1 is inactivated, Gaf1 becomes dephosphorylated and enters the nucleus. Gaf1 was recently shown to negatively regulate the transcription induction of ste11+, a major regulator of sexual development. Our findings support a model of a two-faceted role of Gaf1 during nitrogen stress. Gaf1 positively regulates genes that are induced early in the response to nitrogen stress, while inhibiting later responses, such as sexual development. Taking these results together, we identify Gaf1 as a novel target for TORC1 signaling and a step-like mechanism to modulate the nitrogen stress response.

IMPORTANCE

TOR complex 1 (TORC1) is an evolutionary conserved protein complex that positively regulates growth and proliferation, while inhibiting starvation responses. In fission yeast, the activity of TORC1 is downregulated in response to nitrogen starvation, and cells reprogram their transcriptional profile and prepare for sexual development. We identify Gaf1, a GATA-like transcription factor that regulates transcription and sexual development in response to starvation, as a downstream target for TORC1 signaling. Under nitrogen-rich conditions, TORC1 positively regulates the phosphorylation and cytoplasmic retention of Gaf1 via the PP2A-like phosphatase Ppe1. Under nitrogen stress conditions when TORC1 is inactivated, Gaf1 becomes dephosphorylated and enters the nucleus. Budding yeast TORC1 regulates GATA transcription factors via the phosphatase Sit4, a structural homologue of Ppe1. Thus, the TORC1-GATA transcription module appears to be conserved in evolution and may also be found in higher eukaryotes.

INTRODUCTION

Nitrogen availability is a major determinant of cell growth that is sensed through highly interconnected signaling networks to achieve optimum responses to changes in the nutritional conditions. The TOR (target of rapamycin [sirolimus]) pathway is a central regulator of cell growth in response to nutrient availability (1). TOR is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine kinase that was isolated as the target of the immunosuppressive and anticancer drug rapamycin (2). TOR exists in two distinct evolutionary conserved complexes, termed TOR complex 1 (TORC1) and TOR complex 2 (TORC2), that are controlled by distinct upstream inputs and produce differential downstream outputs (1, 3). Disruption of TORC1 in many eukaryotes, including yeast, nematodes, flies, and mammals, results in cellular phenotypes that resemble starvation (4, 5). Nitrogen and amino acid sufficiency play a major role in signaling environmental cues to TORC1 in yeast and mammalian cells in a mechanism that involves the TSC (tuberous sclerosis complex)-Rheb (Ras homologue enriched in brain) module and the Ras-related GTPase (Rag) heterodimeric complexes (6). TORC2 has also been linked to nutritional signals; however, loss of TORC2 causes diverse effects in different species (7). More recently, the Shiozaki lab and we have shown that the activity of TORC2 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe is specifically regulated by glucose but not nitrogen availability (8, 9).

Two TOR homologues exist in S. pombe, Tor1 and Tor2. These were named in the order of their discovery (10). Tor2 is the catalytic subunit of TORC1, the complex that also contains Mip1 (Raptor). Tor1 is the catalytic subunit of TORC2, the complex that also contains Ste20 (Rictor) and Sin1 (11, 12). S. pombe TORC1 is essential for cell growth. Overexpression of TORC1 (Tor2) inhibits sexual differentiation, mating, and meiosis (13), while disruption of TORC1 (e.g., tor2-ts or mip1-ts alleles) results in a phenotype that highly resembles nitrogen starvation: cells arrest their growth in the G1 phase of the cell cycle as small and rounded cells, induce expression of nitrogen starvation-specific genes, and are derepressed for sexual development (12–15). It was recently shown that one of the mechanisms by which TORC1 negatively regulates sexual development is phosphorylation and stabilization of Mei2, an RNA binding protein critical for the switch from vegetative growth to meiosis (16). Unlike TORC1, S. pombe TORC2 is not essential for growth. Disruption of TORC2 (e.g., ∆tor1, ∆ste20, and ∆sin1) results in pleiotropic defects, including the inability to initiate sexual development or acquire stationary-phase physiology (10, 17), delay in entry to mitosis (18–20), decrease in amino acid uptake (21), sensitivity to osmotic stress, oxidative stress, high or low temperature (10, 17), inability to grow in low glucose (17, 22), and inability to induce gene silencing, tolerate DNA damaging conditions, or maintain a proper length of the telomeres (19, 23). S. pombe TORC2 mediates its functions via phosphorylation and activation of the AGC kinase Gad8 (8, 24, 25).

Rapamycin does not inhibit growth of wild-type S. pombe cells (26). However, disruption of the components of the TSC complex, tsc1+ and tsc2+, that negatively regulate TORC1 results in a rapamycin-sensitive phenotype under nitrogen-poor conditions, when the sole nitrogen source in the growth medium is proline (15). The sensitivity of tsc mutant cells to rapamycin is mediated via inhibition of TORC1 (and not TORC2) and suppressed by overexpression of isp7+. Isp7 is a member of the family of 2-oxoglutarate-Fe(II)-dependent oxygenases. Isp7 regulates amino acid uptake through transcription regulation of general and specific amino acid permeases (27). The transcript of isp7+ is strongly upregulated following inactivation of TORC1 or in response to nitrogen stress (complete withdrawal of nitrogen from the growth medium or its replacement with a poor nitrogen source) (27). However, isp7+ suppresses the induction of many nitrogen stress-induced genes, similarly to TORC1 (27). Consistently, isp7+ positively regulates TORC1 activity, and its overexpression results in activation of TORC1 under nitrogen stress conditions. In contrast, TORC2 is required for expression of isp7+, while Isp7 inhibits TORC2 activity (27). Thus, isp7+ lies both upstream and downstream of TORC1 and TORC2.

We show here that the GATA transcription factor Gaf1 is required for the expression of isp7+ via three canonical GATA motifs that lie in the promoter region of isp7+. Similar to the regulation of the budding yeast nitrogen-sensitive GATA transcription factors Gln3 and Gat1 (28–30), dephosphorylation of Gaf1 and its translocation to the nucleus are negatively regulated by TORC1 via the PP2A-like phosphatase Ppe1. Interestingly, while we show that Gaf1 is critical for induction of isp7+ expression in response to nitrogen stress, a recent paper (31) demonstrated that Gaf1 inhibits the expression of ste11+, a delayed nitrogen stress-induced gene that is critical for sexual development. We found that TORC1-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear localization of Gaf1 upon nitrogen stress are rapid and transient, consistent with a step-like mechanism in which Gaf1 positively regulates early nitrogen starvation-induced genes but inhibits delayed nitrogen starvation-induced genes.

RESULTS

The GATA transcription factor Gaf1 positively regulates the expression of isp7+.

We have previously shown that the 2-oxoglutarate-Fe(II) dependent oxygenase isp7+ has a central role in amino acid homeostasis via the TOR signaling pathway (27). isp7+ is preferentially transcribed upon shift to nitrogen stress conditions (no nitrogen or proline as the sole nitrogen source). In turn, isp7+ regulates the expression of several amino acid permeases in a fashion similar to that of TORC1 and opposite to that of TORC2 (27). In the present study, we were interested in finding the mechanism by which the TOR signaling controls the expression of isp7+.

By examination of the upstream noncoding region of isp7+, we identified three potential GATA motifs (AGATAA) sequences. The presence of several GATA motifs is a good indicator for GATA transcription factor-dependent transcription (32). Thus, we examined whether isp7+ transcription is regulated by any of the known GATA transcription factors in S. pombe. According to PomBase (http://www.pombase.org/), S. pombe contains four nonessential GATA transcription factors: Gaf1, Gaf2/Fep1, Ams2, and the uncharacterized GATA-like transcription factor SPCC1393.08. We examined the transcription level of isp7+ in cells with disruptions of each of these four factors. This analysis revealed that the transcript level of isp7+ is reduced only in Δgaf1 mutant cells, on both rich (Fig. 1A) and minimal (Fig. 1B) media. In addition, unlike wild-type cells, no induction of isp7+ expression was observed in Δgaf1 mutant cells upon a shift to proline (Fig. 1B). We thus concluded that Gaf1 is required for expression of isp7+ under normal growth conditions and for its induction in response to poor nitrogen conditions.

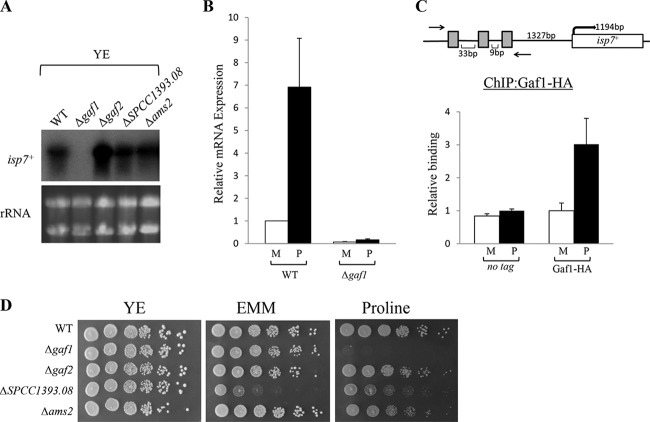

FIG 1 .

Gaf1 positively regulates the transcription of isp7+. (A) Gaf1 is required for transcription of isp7+. Northern blot analysis of wild type (WT) or mutant cells carrying a deletion of the GATA transcription factor encoded by gaf1+, gaf2+, SPCC1393.08+, or ams2+ was carried out. Cells were grown to mid-log phase in rich medium YE (Yeast Extract) before RNA was extracted. rRNA was used as a loading control. (B) Gaf1 is required for the upregulation of isp7+ in response to a poor-quality nitrogen source. Wild-type or Δgaf1 cells were grown in minimal (M) medium and shifted to proline for 30 min (P). Total RNA was extracted and analyzed by RT-qPCR, using act1+ as a reference. Expression levels were quantitated using the comparative CT method. (C) Gaf1 is physically associated with the promoter region of the isp7+ gene under nitrogen stress conditions. Gaf1 occupancy at the promoter region of isp7+ was assessed by ChIP analysis of chromatin extracts in Gaf1-HA strains. An untagged strain was used as control. Cells were grown in minimal (M) medium and shifted to proline for 1 h (P). Occupancy levels were quantified by real-time PCR. (D) Gaf1 is required for growth on proline. Serial dilutions of exponentially growing wild-type (WT), Δgaf1, Δgaf2, ΔSPCC1393.08, and Δams2 strains were spotted on YE medium, EMM, or proline medium.

To examine whether Gaf1 directly binds sequences spanning the three GATA motifs upstream of isp7+, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (ChIP) in which Gaf1 was chromosomally tagged with three copies of the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (see Materials and Methods). The levels of Gaf1-HA binding to the promoter region of isp7+ on minimal medium are similar to the levels observed with an untagged strain. However, a significant increase in Gaf1-HA binding was observed following a shift for 1 h to proline (Fig. 1C). Therefore, it is likely that Gaf1-HA directly binds the upstream region of isp7+ under nitrogen stress conditions. Under normal conditions, Gaf1-HA may not bind the promoter region of isp7+ directly, or our assay is not sensitive enough to detect binding under these conditions.

We examined the growth of mutant cells with disruptions of each of the four transcription factors. Disruption of gaf2+ or ams2+ does not result in a significant change in the growth rate compared to that of wild-type cells, while disruption of SPCC1393.08 results in a slow-growth phenotype on either minimal or proline plates (Fig. 1D). Δgaf1 mutant cells are unable to grow when the sole nitrogen source in the medium is proline (Fig. 1D). Previously, it was reported that Δgaf1 mutant cells grow poorly on plates containing only small amounts of amino acids but do not show a poor-growth phenotype on low-glucose medium (31). Thus, Gaf1 is specifically required for growth under poor nitrogen conditions. isp7+ is not required for growth on proline in a wild-type background (27). However, double-mutant cells carrying disruption of isp7+ together with disruption of the TSC complex (Δtsc1 or Δtsc2) are unable to grow on proline. Thus, Gaf1 may affect several redundant pathways that together support growth under nitrogen stress conditions.

Gaf1 regulates the transcription of isp7+ via canonical GATA motifs.

We next examined the role of the three GATA motifs present upstream of the isp7+ open reading frame (Fig. 2A). To this end, we used a plasmid-borne isp7-lacZ fusion construct in which the bacterial lacZ gene is expressed under the regulation of isp7+ promoter as described in reference 27. As expected, isp7-lacZ activity is increased in wild-type cells upon a shift to proline (Fig. 2C). Also, consistent with our previous Northern blot analyses for isp7+ (27), isp7-lacZ activity decreases in cells with a disruption of TORC2 (Δtor1, Δste20, and Δsin1) but increases upon inactivation of Tor2 (TORC1) (Fig. 2B and C). We noted that the isp7-lacZ activity is low in TORC2 mutant cells but is still induced upon a shift to proline (Fig. 2C). Also, the high level of isp7-lacZ activity in TORC1 mutant cells in minimal medium undergoes further induction upon a shift to proline (Fig. 2B). Thus, the upregulation of isp7+ in response to poor nitrogen source involves both TORC1 and TORC2, or possibly an additional, yet-to-be-characterized pathway. Deletion of gaf1+ reduces isp7-lacZ activity on minimal medium and abolishes the induction in proline medium (Fig. 2C), consistent with our finding that Gaf1 regulates transcription of isp7+ under optimal conditions and in response to changes in nitrogen availability (Fig. 2B).

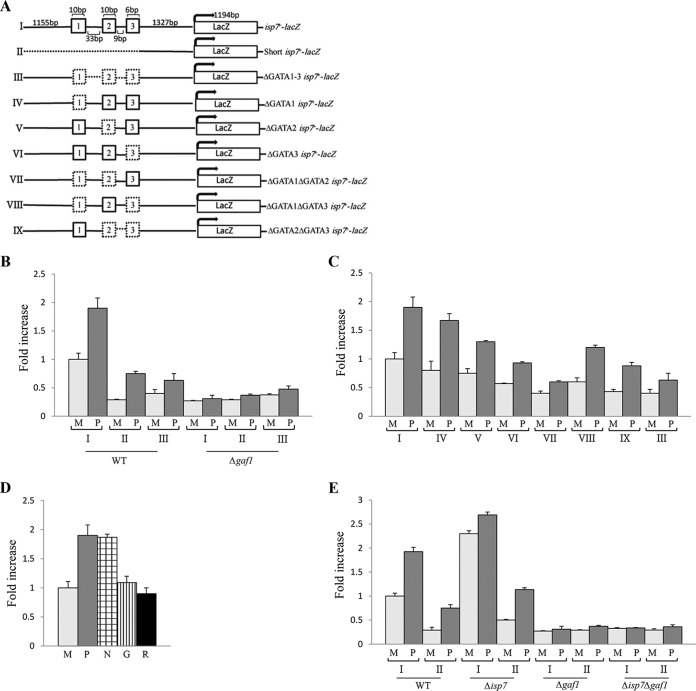

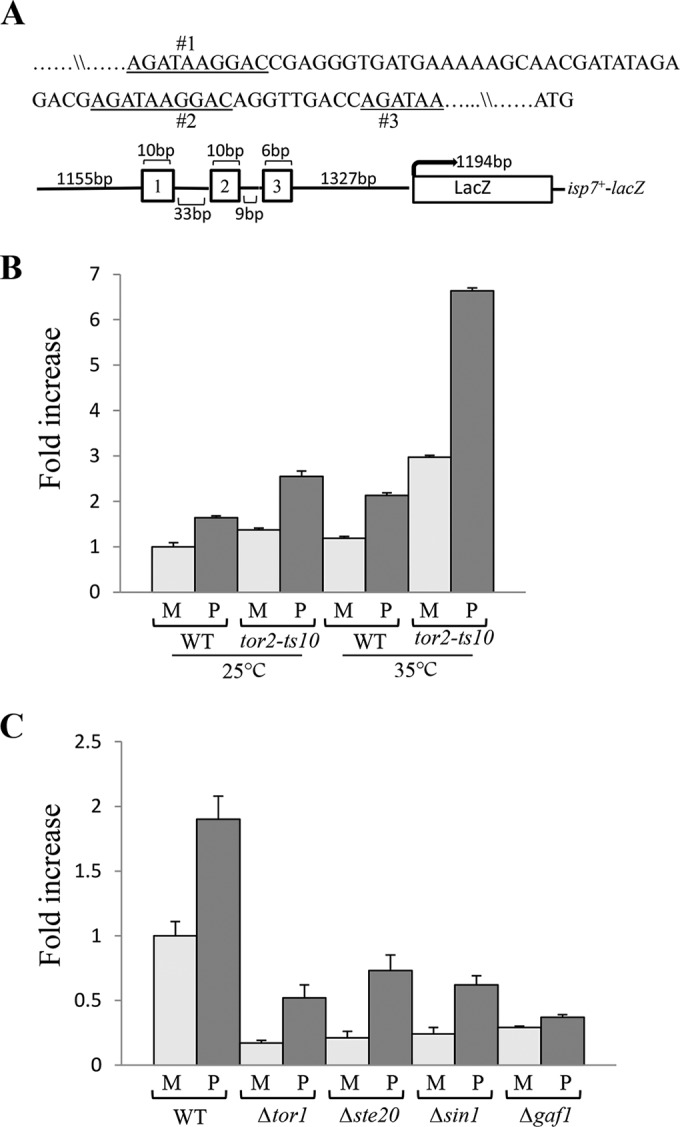

FIG 2 .

isp7-lacZ activity is positively regulated by TORC2 and negatively regulated by TORC1. (A) Schematic representation of the isp7-lacZ fusion construct. The three GATA motifs in the isp7+ promoter region are numbered. (B) Increase in lacZ activity in TORC1 mutant cells carrying the isp7-lacZ fusion construct. Wild-type or tor2-ts10 cells containing isp7-lacZ were grown in minimal medium (M) at 25°C (0 h), shifted to 35°C for 2 h (restrictive temperature) and shifted to proline (P) at 35°C for additional 2 h. Proteins were extracted, and β-galactosidase activity was measured. (C) Decrease in lacZ activity in TORC2 or Δgaf1 mutant cells carrying the isp7-lacZ fusion construct. Wild-type cells or cells with disruptions of specific subunits of TORC2 (Δtor1, Δsin1, Δste20, or Δgaf1 mutant cells) containing isp7-lacZ were grown to mid-log phase in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline (P) for 2 h. Proteins were extracted, and β-galactosidase activity was measured.

We next created a series of constructs in which one or more of the GATA motifs were removed (Fig. 3A). A short isp7-lacZ construct containing a 1,223-bp deletion of the 5′ end of isp7-lacZ (construct II) or deletion of a 68-bp stretch flanking the three GATA motifs (construct III) reduces isp7-lacZ activity in minimal and proline media (Fig. 3B), consistent with a transcription-regulatory role for the GATA motifs. The deletion constructs still allow a certain level of induction of isp7-lacZ activity in response to a shift to proline; in contrast, disruption of gaf1+ abolishes induction activity (Fig. 3B). Thus, Gaf1 may have a minor effect on isp7+ expression independently of the three GATA motifs.

FIG 3 .

isp7-lacZ activity is regulated by the three GATA motifs located upstream of isp7+. (A) Schematic representation of isp7-lacZ fusion constructs. Dashed lines represent deleted sequences. (B) isp7-lacZ fusion constructs lacking all three GATA motifs or mutant cells lacking the transcription factor Gaf1 show reduced lacZ activity in minimal or proline medium. Wild-type or Δgaf1 cells carrying isp7-lacZ fusion constructs I to III were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline (P) for 2 h. Proteins were extracted, and β-galactosidase activity was measured. (C) Deletion of any combination of two GATA motifs reduced lacZ activity. Wild-type cells carrying isp7-lacZ fusion constructs I or III to IX were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline (P) for 2 h. Proteins were extracted, and β-galactosidase activity was measured. (D) isp7-lacZ activity is induced in response to nitrogen stress but not glucose reduction or rapamycin addition. Wild-type cells containing isp7-lacZ were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted for 2 h to proline (P), minimal medium without a nitrogen source (N), low-glucose medium (0.2% glucose) (G), or minimal medium with rapamycin (R). (E) Isp7 negatively regulates isp7-lacZ activity. Wild-type (WT), Δisp7, Δgaf1, or Δgaf1 Δisp7 cells carrying isp7-lacZ fusion construct I or II were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline (P) for 2 h before lacZ activity was measured.

To examine the role of each of the GATA motifs, independently or in combination with other GATA motifs, we created additional constructs (IV to IX). Disruption of motif 1 or 2 results in a very minor effect on isp7-lacZ activity (Fig. 3C, constructs IV and V). In contrast, disruption of motif 3 alone shows a significant reduction in isp7-lacZ activity (Fig. 3C, construct VI). Disruption of any two motifs resulted in low level of isp7-lacZ activity in minimal medium (Fig. 3C). Thus, our results indicate that motif 3 or any other combination of two motifs is critical for transcriptional induction.

Similar to the effect upon shift to proline, we found that isp7-lacZ activity is induced upon shift to medium with no nitrogen. In contrast, upon shift to 0.2% glucose, isp7-lacZ activity is not induced (Fig. 3D), indicating that the expression of isp7+ is specifically induced in response to nitrogen but not glucose availability. Rapamycin has no effect on isp7-lacZ activity (Fig. 3D), consistent with the limited effects of rapamycin on TORC1-dependent activities in fission yeast.

Isp7 negatively regulates its own transcription.

Genome-wide transcriptional profiling indicated an extensive overlap between genes that are upregulated by loss of isp7+ and genes that are upregulated in response to nitrogen starvation or TORC1 inactivation (27). Thus, while the transcript level of isp7+ is induced upon nitrogen stress, Isp7 is a negative regulator of nitrogen starvation-induced genes. This paradoxical behavior of isp7+ can be explained by the presence of a negative feedback loop, in which Isp7 negatively regulates its own expression. To test this possibility, we examined the level of isp7-lacZ activity in Δisp7 mutant cells. We found that in Δisp7 mutant cells, the activity of isp7-lacZ is significantly induced on minimal medium, exceeding the levels observed in wild-type cells upon a shift to proline (Fig. 3E). The elevated level of isp7-lacZ activity in Δisp7 cells is consistent with our suggestion that Isp7 negatively regulates its own transcription. Disruption of gaf1+ abolishes isp7-lacZ activity in Δisp7 cells (Fig. 3E), indicating the requirement for Gaf1 activity in this genetic background.

Intracellular localization of Gaf1 is sensitive to nitrogen stress.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, TORC1 affects the transcription of genes that are involved in the nitrogen stress response by regulating the phosphorylation status and localization of the GATA transcription factors Gln3 and Gat1 (28–30). To examine the cellular localization of Gaf1, we expressed a Gaf1-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein from the Gaf1 promoter at its chromosomal locus. The Gaf1-GFP fusion protein is functional, as it complemented the inability of Δgaf1 to grow on proline (data not shown). We observed that the Gaf1-GFP fusion protein is dispersed through the cytoplasm in minimal medium but translocates into the nucleus following 1 h of shift to proline or no nitrogen (Fig. 4A). The intracellular localization of Gaf1 does not change in response to glucose depletion or rapamycin addition (Fig. 4A), suggesting that Gaf1 localization is specifically regulated in response to nitrogen stress and is insensitive to rapamycin. These findings are consistent with the induction of isp7-lacZ activity in response to nitrogen but not glucose depletion and the insensitivity of isp7-lacZ activity to rapamycin (Fig. 3D). Note that although Gaf1-GFP is mainly cytoplasmic under nitrogen-rich conditions, Gaf1 is nevertheless required for isp7+ transcription even under rich conditions (Fig. 1A and B). Thus, a subpopulation of Gaf1 may reside in the nucleus under nitrogen-rich conditions, but translocation of Gaf1 to the nucleus under nitrogen stress results in strong binding to specific promoter regions (Fig. 1C) and transcriptional induction.

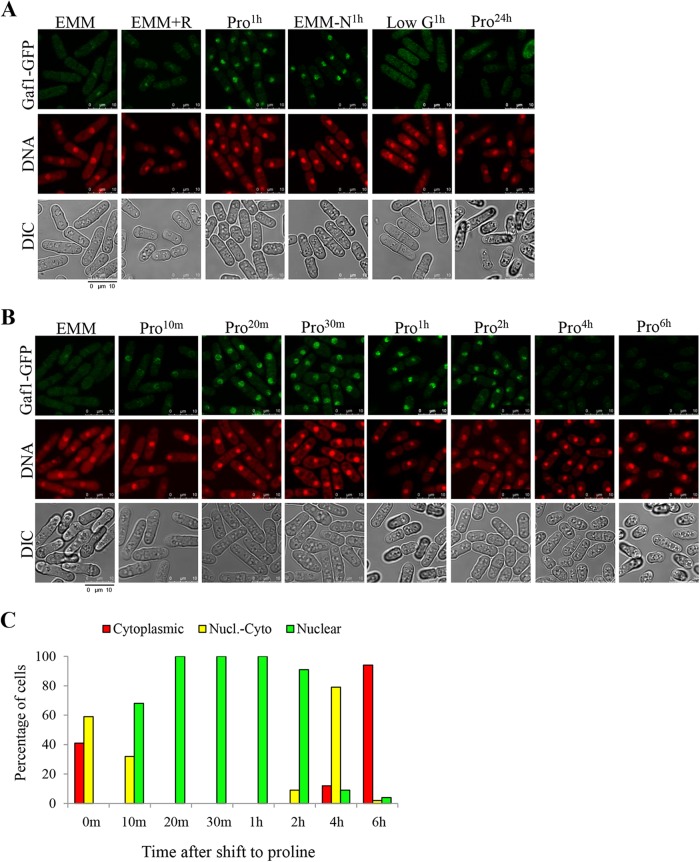

FIG 4 .

Rapid and transient nuclear accumulation of the transcription factor Gaf1 in response to nitrogen stress. (A) Gaf1 accumulates in the nucleus in response to nitrogen stress. Wild-type cells carrying Gaf1-GFP were grown in minimal medium (EMM) or proline medium (Pro24h) or transferred from EMM to proline-containing medium (Pro1h), low-glucose medium (low G1h), no-nitrogen medium (EMM-N1h), or EMM with rapamycin (EMM+R) for 1 h. (B and C) Time course analysis of the translocation of Gaf1 from the cytoplasm into the nucleus following a shift from minimal to proline media. Wild-type cells carrying Gaf1-GFP were grown to mid-log phase in minimal medium (EMM) and shifted to proline (Pro) for 10 min, 20 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, or 6 h. Cells were scored for intracellular Gaf1-GFP localization using criteria described in Materials and Methods. Nuclei were stained with DRAQ5. Cells were visualized by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. Scale bar, 10 µm.

A nuclear accumulation of Gaf1 was not observed when cells were grown overnight on proline medium (Fig. 4A), suggesting that the translocation of Gaf1 to the nucleus is transient. Indeed, a time course analysis indicated that Gaf1 starts to accumulate in the nucleus within 10 min following a shift to proline and becomes primarily nuclear within 20 min in proline (Fig. 4B). Within 4 h in proline, Gaf1 becomes partially cytoplasmic, and it is mainly cytoplasmic by 6 h in proline (Fig. 4B). To quantify the intracellular Gaf1-GFP localization, we followed the categories previously described for localization of Gln3 or Gat1 in the nucleus (33). Cells were classified into three categories: cytoplasmic (cytoplasmic Gaf1-GFP fluorescence), nuclear-cytoplasmic (Gaf1-GFP fluorescence appearing in the cytoplasm as well as colocalizing with the nuclear fluorescent DNA dye DRAQ5), and nuclear (Gaf1-GFP fluorescence colocalizing with DRAQ5-positive material) (Fig. 4C). Our qualitative and quantitative results indicate that a shift to nitrogen-poor conditions brings about a rapid and transient nuclear accumulation of Gaf1 (Fig. 4B and C).

TORC1 regulates Gaf1 intracellular localization.

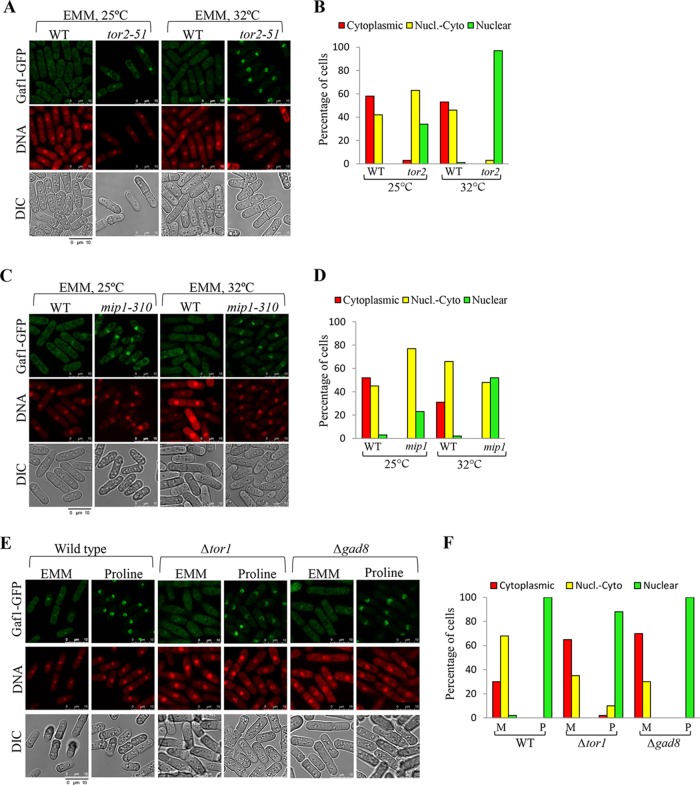

We next examined the effects of disrupting TORC1 or TORC2 on the localization of Gaf1-GFP. Inactivation of the TORC1 components Tor2 and Mip1 using the temperature-sensitive alleles tor2-51 and mip1-310 results in nuclear localization of Gaf1-GFP in minimal medium, indicating that TORC1 negatively regulates Gaf1 nuclear accumulation under nitrogen sufficiency conditions ("Fig. 5 to D). Disruption of the catalytic subunit of TORC2 (Δtor1) or the TORC2 downstream kinase Gad8 (Δgad8) led to a stronger cytoplasmic signal of Gaf1-GFP, compared with nuclear-cytoplasmic signal in minimal medium (Fig. 5E and F). This finding may correspond to the decrease in isp7+ expression in TORC2 mutant cells (27) (Fig. 2C). However, mutations in TORC2 do not significantly affect the nuclear accumulation of Gaf1-GFP upon a shift to proline (Fig. 5E and F). Thus, TORC1 is the main regulator of Gaf1 localization in response to nitrogen stress.

FIG 5 .

Gaf1 localization in the nucleus is controlled by TORC1. (A to D) TORC1 negatively regulates the translocation of Gaf1 from the cytoplasm into the nucleus. Wild-type, tor2-51, or mip1-310 cells carrying Gaf1-GFP were grown to mid-log phase in minimal medium (EMM) at 25°C (0 h) and then shifted to 32°C for 4 h to inactivate Tor2 or Mip1. Cells were scored for intracellular Gaf1-GFP localization as for Fig. 4C. (E and F) TORC2-Gad8 has a minor effect on Gaf1 localization. Wild-type, Δtor1, or Δgad8 cells carrying Gaf1-GFP were grown in minimal medium and shifted to proline for 1 h (Pro1h). Cells were scored for intracellular Gaf1-GFP localization as described above.

Gaf1 is dephosphorylated in response to nitrogen stress.

We used the Gaf1-HA fusion protein to follow putative posttranslational modifications of Gaf1 in response to nutritional changes. An increase in the electrophoretic mobility of Gaf1-HA was detected in SDS-PAGE gels when cells were shifted from minimal to proline media or to a medium lacking nitrogen (Fig. 6A). No change in the electrophoretic mobility was observed upon a shift to low glucose (Fig. 6A). Thus, similar to regulation of the activity of isp7-lacZ or Gaf1-GFP nuclear localization, the mobility shift of Gaf1-HA is sensitive to changes in the availability of nitrogen, but not glucose. Also, similar to the transient nature of the localization of Gaf1-GFP into the nucleus, the decrease in Gaf1-HA electrophoretic mobility shift was transient. The fast-migrating band was already observed 20 min following the shift to proline (Fig. 6B). Two to six hours following the shift to proline, the slower-migrating band reappeared, and both the slower and faster bands were visible (Fig. 6B; also, see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). A similar pattern of changes in the electrophoretic mobility of Gaf1-HA is observed after a shift to a medium lacking nitrogen (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

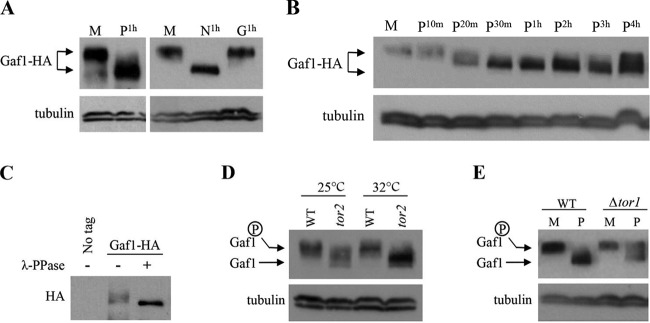

FIG 6 .

Gaf1 phosphorylation is regulated by nitrogen availability and TORC1 activity. (A) The electrophoretic mobility of Gaf1-HA increases in response to nitrogen stress. Wild-type cells carrying Gaf1-HA were grown to mid-log phase in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline (P1h), minimal medium without a nitrogen source (N1h), or low glucose medium (0.2% glucose) (G1h) for 1 h. Gaf1-HA was detected by anti-HA antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (B) Time course analysis of Gaf1-HA electrophoretic mobility upon a shift from minimal to proline medium. Wild-type cells carrying Gaf1-HA were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline for 10 min, 20 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, and 4 h. Gaf1-HA was detected by anti-HA antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) The slower-migrating band of Gaf1-HA represents protein phosphorylation. Wild-type cells carrying Gaf1-HA were grown in minimal medium (M) to mid-log phase before proteins were extracted and immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies. λ-Phosphatase was added to immunoprecipitated Gaf1-HA. A nontagged strain was used as a negative control. (D) Gaf1 phosphorylation is regulated by TORC1. Wild-type and tor2-51 cells carrying Gaf1-HA were grown in minimal medium at 25°C and shifted to 32°C for 4 h. Gaf1-HA was detected by anti-HA antibodies. (E) Gaf1 is abnormally phosphorylated in proline medium in TORC2 mutant cells. Wild-type and Δtor1 cells carrying Gaf1-HA were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline (P) for 1 h. Gaf1-HA was detected by anti-HA antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control.

When λ-phosphatase was added to immunoprecipitated Gaf1-HA, only the faster-migrating band was observed, suggesting that the mobility shift is due to the phosphorylation status (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that Gaf1 is phosphorylated under nitrogen-rich conditions, when Gaf1 is mainly cytoplasmic but becomes dephosphorylated in response to nitrogen stress when Gaf1 localizes to the nucleus. Similar to Gaf1 nuclear localization, dephosphorylation of Gaf1 in response to nitrogen stress is rapid and transient.

Gaf1 phosphorylation is positively regulated by TORC1.

We next asked whether the phosphorylation of Gaf1 is controlled by the TORC1 or TORC2 complexes. We found that the tor2-51 mutation abolishes the presence of the phosphorylated form of Gaf1-HA in minimal medium (Fig. 6D), suggesting that TORC1 is required for the phosphorylation of Gaf1 under nitrogen sufficiency conditions. As previously indicated, the temperature-sensitive tor2-51 mutant allele produces a partially inactive protein at the permissive temperature (27). Consistently, dephosphorylation of Gaf1 in tor2-51 mutant cells was already observed at the permissive temperature (Fig. 6D). The AGC kinases Psk1, Sck1, and Sck2 are phosphorylated in a nutrient-dependent fashion by TORC1 (34). Disruption of Psk1, disruption of both Sck1 and Sck2, or a disruption of all three kinases did not affect the subcellular localization of Gaf1 (see Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material). Likewise, the Δpsk1 mutation and the Δsck1 Δsck2 mutation did not affect the phosphorylation status of Gaf1 in response to nitrogen stress (see Fig. S2C in the supplemental material). Thus, TORC1 regulates Gaf1 at least largely independently of Psk1, Sck1, and Sck2. Disruption of TORC2 (Δtor1) led to the persistence of the slowly migrating band of Gaf1-HA upon a shift to proline (Fig. 6E), suggesting an abnormal increase in the phosphorylated form of Gaf1 under nitrogen stress conditions. Since we do not see a major effect of Δtor1 on nuclear localization of Gaf1-GFP, we speculate that localization may occur at least partially independently of the phosphorylation status; alternatively, our localization assay may not be as sensitive as the Gaf1-HA band shift assay. In any case, the effects of TORC1 mutants on Gaf1 phosphorylation and nuclear localization are stronger than the effects of TORC2 mutant cells.

TORC1 regulates the phosphorylation status of Gaf1 via the Ppe1 phosphatase.

Since Gaf1 is dephosphorylated upon shift to proline, we asked whether Gaf1 is regulated by a specific phosphatase. Disruption of the PP2A-like phosphatase gene ppe1+ abolished Gaf1 dephosphorylation (Fig. 7A). Disruption of the PP2A gene orthologs ppa1+ and ppa2+ only partially affected the status of phosphorylation of Gaf1 in response to proline (Fig. 7A). Thus, Ppe1 is the main relevant PP2A-like phosphatase for Gaf1 dephosphorylation. We observed a reduction in Gaf1-GFP nuclear localization upon the shift to proline in Δppe1 mutant cells compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 7B and C), indicating that Ppe1 is also required for Gaf1 localization to the nucleus. Consistently, Ppe1 is required for the induction of isp7-lacZ activity upon a shift to proline (Fig. 7D), suggesting that Ppe1 plays an important role in positively regulating Gaf1 activity in vivo. Neither overexpression of ppe1+ nor disruption of sds23+ (encoding a phosphatase inhibitor of Ppe1 and other PP2A-related phosphatases [35]) affected Gaf1 dephosphorylation (see Fig. S3A and B in the supplemental material). Thus, while Ppe1 is required for dephosphorylation of Gaf1, its overexpression does not affect the status of phosphorylation of Gaf1.

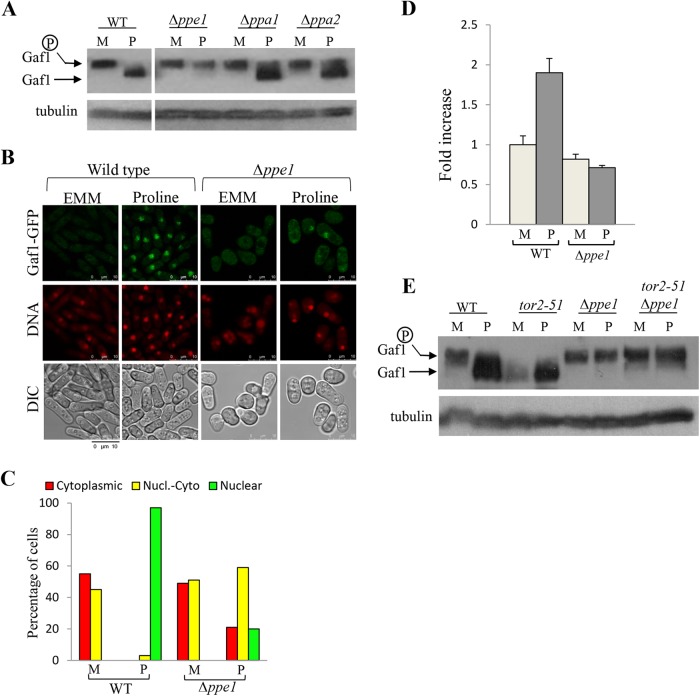

FIG 7 .

Dephosphorylation and localization of Gaf1 is controlled by the phosphatase Ppe1. (A) Gaf1 dephosphorylation is mainly regulated by Ppe1. Wild-type, Δppe1, Δppa1, or Δppa2 cells carrying Gaf1-HA were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline (P1h) for 1 h. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (B and C) Ppe1 positively regulates the translocation of Gaf1 from the cytoplasm into the nucleus. Wild-type or Δppe1 cells carrying Gaf1-GFP were grown in minimal medium and shifted to proline for 1 h (Pro1h). Cells were scored for intracellular Gaf1-GFP localization. Nuclei were stained with DRAQ5. Cells were visualized by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. Scale bar, 10 µm. (D) isp7-lacZ fusion constructs show a decrease in lacZ activity in Δppe1 mutant cells. Wild-type or Δppe1 cells, containing isp7-lacZ, were grown to mid-log phase in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline (P) for 2 h. Proteins were extracted, and LacZ activity was measured as described above. (E) TORC1 negatively regulates Ppe1. Wild-type, tor2-51, Δppe1, or tor2-51 Δppe1 cells carrying Gaf1-HA were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline (P1h) for 1 h at 28°C. Tubulin was used as a loading control

Our findings indicate that Gaf1 dephosphorylation and nuclear localization are negatively regulated by TORC1 and positively regulated by Ppe1. In S. cerevisiae cells, TORC1 indirectly regulates the activity of the phosphatase Sit4, a structural homologue of Ppe1, and in turn controls the nuclear localization of Gln3 (36). If S. pombe TORC1 also regulates the status of phosphorylation of Gaf1 via Ppe1, it is expected that in cells carrying Δppe1 together with inactivation of TORC1, the status of phosphorylation of Gaf1 will be similar to that of single Δppe1 mutant cells. In order to examine the genetic relationship between ppe1+ and TORC1 (tor2+), we constructed aΔppe1 tor2-51 double-mutant strain. Since the Δppe1 single-mutant cells are cold sensitive, we grew the Δppe1 tor2-51 double-mutant cells at 28°C, an intermediate temperature at which the Δppe1 and the tor2-51 single-mutant cells can grow. Gaf1 was completely dephosphorylated in tor2-51 mutant cells at 28°C, indicating that the function of tor2-51 is severely compromised at this temperature (Fig. 7E). We observed no dephosphorylation of Gaf1 upon a shift to proline in the double-mutant strain, similar to Δppe1 single-mutant cells (Fig. 7E). Thus, our results support a model in which TORC1 indirectly regulates the status of phosphorylation of Gaf1, via Ppe1 (Fig. 8).

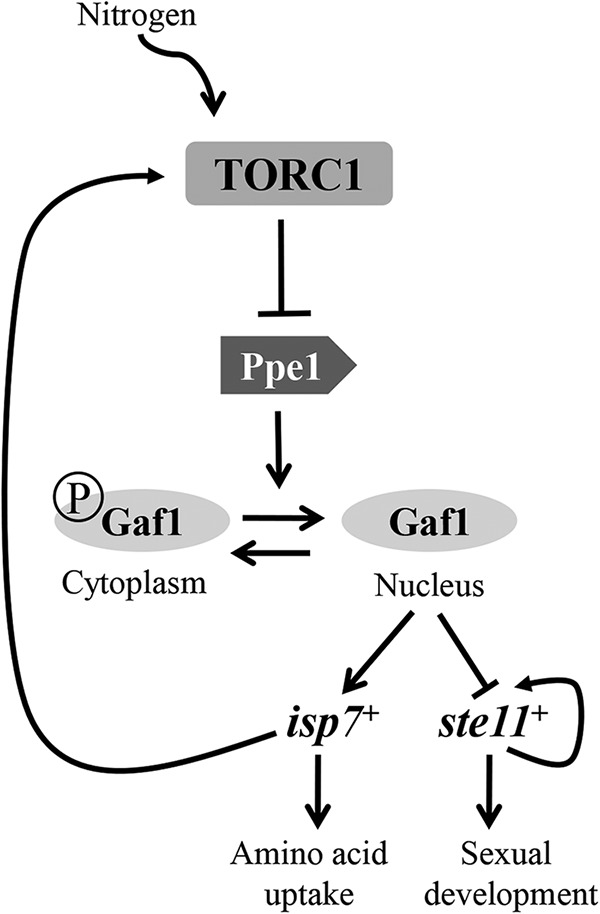

FIG 8 .

TORC1 regulates the nitrogen starvation response via localization of Gaf1 into the nucleus. A schematic model is shown. Under good nitrogen conditions, TORC1 is active and Gaf1 is phosphorylated and retained in the cytoplasm. Under nitrogen stress conditions, TORC1 becomes inactive and Ppe1, acting downstream of TORC1, becomes active. Consequently, Gaf1 is dephosphorylated and enters the nucleus. Upon entrance into the nucleus, Gaf1 positively regulates early nitrogen stress-induced genes, such as isp7+, while negatively regulating the transcription of delayed nitrogen stress-induced genes, such as ste11+. High levels of isp7+ can induce TORC1 activity under poor nitrogen conditions (27), leading to inactivation of Gaf1 and negative regulation of isp7+ expression. Previous studies have also indicated a positive autoregulation of ste11+ (44).

DISCUSSION

All GATA transcription factors contain one or two zinc fingers that recognize the 6-bp consensus DNA sequence 5′ HGATAR 3′ (H = T, A, or C; R = A or G) in the promoter regions of the target genes. Gaf1 (GATA-factor like gene), a GATA-family zinc finger transcription factor in fission yeast, was previously suggested to play a role in transactivation of target genes (37, 38). A more recent paper reported that Gaf1 binds upstream of ste11+, a gene encoding a transcription factor that plays a major role in sexual development, and negatively regulates ste11+ expression (31). Here, we present the first detailed analysis of a gene target that requires Gaf1 for its expression. Gaf1 is required for basal and induced levels of isp7+ via binding of the region containing the three GATA motifs upstream of the open reading frame (ORF) of isp7+. We also show that all three GATA motifs participate in the regulation of isp7+.

TORC1 is a negative regulator of transcription of isp7+ (27). Here we show that TORC1 regulates the transcription of isp7+ by regulating Gaf1 phosphorylation status and subcellular localization. Under good nitrogen conditions, TORC1 is active and Gaf1 is phosphorylated and retained in the cytoplasm. Under nitrogen stress conditions, TORC1 becomes inactive (27, 39), leading to rapid and transient dephosphorylation of Gaf1 and its accumulation within the nucleus. In turn, Gaf1 regulates the expression of nitrogen stress-induced genes (Fig. 8). Dephosphorylation and nuclear localization of Gaf1 occurred concomitantly, while disrupting dephosphorylation of Gaf1 by deletion of the phosphatase gene ppe1+ reduced nuclear localization. Thus, our data indicate correlation between the status of phosphorylation of Gaf1 and its nuclear localization. Dephosphorylation of Gaf1 may be required for its entrance into the nucleus; alternatively, TORC1-Ppe1 may regulate Gaf1 phosphorylation and localization independently. To distinguish between these two possibilities, TORC1-dependent phosphorylation sites in Gaf1 should be determined, and mutational analysis should be carried out.

Genetic interactions between TORC1 and Δppe1 mutant cells strongly argue for a model in which TORC1 regulates the status of phosphorylation of Gaf1 in response to nitrogen stress via Ppe1 (Fig. 7E). In S. cerevisiae, the nitrogen catabolic repression (NCR) response is also regulated by TORC1 (ScTORC1) and includes the induction of a large number of genes that are required for scavenging of poor nitrogen sources. Upon nitrogen limitation, ScTORC1 becomes inactive; this subsequently causes a rapid dephosphorylation and translocation of the GATA transcription factors Gln3 and Gat1 to the nucleus and activation of NCR genes (28–30). Moreover, ScTORC1 regulates GATA transcription factors via the phosphatase Sit4, a structural homologue of Ppe1. Thus, our findings support a conserved mechanism in yeast for nitrogen stress response regulation by the TORC1/PP2A-like phosphatase and GATA transcription factors. Certain differences exist, however, between the two yeasts. In S. cerevisiae, glucose starvation or rapamycin addition induced Gln3 and Gat1 dephosphorylation and nuclear localization (28, 40, 41). In contrast, rapamycin or glucose availability did not affect Gaf1 phosphorylation or localization, consistent with the insensitivity of most TORC1 functions to rapamycin and suggesting an exclusive response of the TORC1-Ppe1-Gaf1 pathway to nitrogen starvation.

The contribution of TORC2 to the regulation of Gaf1 activity is less clear. Upon inactivation of TORC2 (e.g., Δtor1), Gaf1 remains partially phosphorylated in response to nitrogen stress, and localization of Gaf1 into the nucleus is only slightly affected. Consistently, our studies demonstrate that TORC2 is required for basal levels of transcription of isp7+ but plays a relative minor role in the induction of expression in response to a shift to proline.

Interestingly, our findings suggest a complex role for Gaf1 in regulating nitrogen stress-induced genes. Gaf1 positively regulates isp7+ (this work), while inhibiting the expression of ste11+ (31). Based on genome-wide expression profiles, Genes that are induced upon nitrogen depletion were classified into three groups: transient, continuous, and delayed (42). According to these studies, isp7+ was classified as a transient gene, as its levels were induced early during nitrogen starvation and returned to basal within 2 to 3 h. We observed that the transcript level of isp7+ is already induced within 15 min after a shift to proline (27), consistent with a role of Isp7 during the initial stages of the nitrogen stress response. In contrast, ste11+, a key regulator of sexual development, was classified as “delayed” (42). The ste11+ transcript and protein levels are induced 4 to 6 h following nitrogen depletion (43). Thus, our findings are consistent with a model in which the response to nitrogen stress is composed of two steps. Immediately after nitrogen starvation, TORC1 is inactivated and Gaf1 becomes dephosphorylated, enters the nucleus, and induces transcription of early, transient nitrogen starvation-induced genes. The localization of Gaf1 in the nucleus is transient; thus, subsequent relocation of Gaf1 into the cytoplasm may allow induction of ste11+ and consequently the transcription of more than 80 genes whose expression is essential for mating (44). isp7+ is most strongly upregulated upon nitrogen starvation, yet Isp7 negatively regulates the expression of general amino acid permease genes (such as per1+ and put4+) and many other nitrogen starvation-induced genes (27). Thus, Isp7 may transmit a nitrogen sufficiency signal during the first hours of nitrogen stress. This may allow cells to prepare for a second wave of transcriptional response to the nitrogen stress, if the stress conditions prevail. In contrast, if good nitrogen conditions are reintroduced, cells can avoid sexual development and keep proliferating. Our proposed model is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated a role for Gaf1 in delaying nitrogen starvation responses (31). Accordingly, although gaf1+ is induced upon nitrogen stress, Gaf1 negatively regulates sexual development, and its disruption results in a high level of mating efficiencies compared with wild-type cells (31). Our data suggest that Gaf1 is a nitrogen stress modulator that is regulated by the TOR pathway in both space and time to enable a suitable response to nitrogen stress.

Given the conservation of the nitrogen response by TOR-dependent regulation of the GATA transcription factors in budding and fission yeast, two highly diverged yeasts, an equivalent developmental choice mechanism may also be conserved in other eukaryotes. Indeed, a response to environmental stress by TOR-dependent regulation of GATA transcription factors was reported to occur in Candida albicans (45), in the fat bodies of ticks (46) and mosquitos (47, 48), and more recently in Caenorhabditis elegans (49). In C. elegans, TOR regulation of the intestinal GATA transcription factor ELT-2 is required for upregulation of glutathione S-transferase GSTO-1, thereby conferring longevity under transient hypoxia (49). Further studies should determine which aspects of the TOR-GATA transcription regulation are conserved and whether additional GATA transcription factors in other eukaryotes play developmental roles in TOR signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast techniques.

Table S1 in the supplemental material shows the list of S. pombe strains used in this work. Unless otherwise specified, S. pombe strains were grown at 30°C in Edinburgh minimal medium (EMM; 5 g/liter NH4Cl) as described before (50). Temperature-sensitive mutants were grown at the permissive temperature (25°C) and shifted to the restrictive temperature (32oC to 35oC) to display their mutant phenotype. For proline medium, the ammonium chloride in the minimal medium was replaced with 10 mM proline. Rapamycin (Holland Moran) was used at a final concentration of 200 ng/ml.

Construction of gaf1-HA and gaf1-GFP.

The C terminus of Gaf1 was tagged with triple HA or GFP. PCR was used to amplify the HA or GFP tags using the pFA6a-3HA-KanMX6 and thepFA6a-GFP-KanMX6 plasmids as templates (51). The PCR fragments were purified and transformed into a 972h− wild-type strain. The DNA fragments were introduced into the genome by homologous recombination. Correct integrations at the gaf1 loci were validated by PCR. The expression of tagged proteins was confirmed by Western blotting.

Gene disruption of Δgaf1, Δgaf2, and ΔSPCC1393.08.

The gaf1, gaf2, and SPCC1393.08 genes were disrupted in wild-type strains via homologous recombination using PCR fragments amplified from the plasmid pFA6a-KanMX6 with suitable primers. Gene replacements were confirmed by PCR.

Construction of lacZ reporter gene.

The isp7+ promoter was fused upstream to the promoterless β-galactosidase ORF of the shuttle vector pSPE356, as described before (27). Subsequent subcloning with suitable primers or site-directed mutagenesis using the DNA polymerase Accuzyme (Bioline) resulted in a series of isp7-lacZ constructs as described in Fig. 3A. DNA sequencing confirmed the presence of the introduced mutations.

Northern blotting.

RNA was prepared using the hot phenol method and subjected to Northern blot analysis as described before (27). Gene-specific probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using a random-primer DNA labeling kit (20-101-25 A; Biological Industries).

RT-qPCR.

RNA was prepared using the hot phenol method and treated with RNase-free RQ1 DNase I (Promega) to remove DNA prior to reverse transcription. One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed with ImProm-II reverse transcriptase (Promega), followed by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) with a Precision Fast qPCR master mix kit (Primer Design). Reactions were performed in triplicate and run on a Step One Plus real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems). Threshold cycle (CT) values for the cDNA of interest were normalized to the CT values of act1+, and relative expression levels were quantified using the comparative method and calculated as 2−ΔΔCT. The amount of expression was expressed relative to the expression level of wild-type cells grown in minimal medium (relative value = 1).

Fluorescence microscopy.

Live cells were observed by Leica TCS SP5 laser confocal microscope with a 63× oil objective. To visualize the nuclei, DRAQ5 (ab108410; Abcam) was used to stain DNA. A 488-nm argon laser was used to excite the GFP fluorescence (emission wavelength, 500 to 550 nm), and a 633-nm HeNe laser was used to excite the DRAQ5 fluorescence (emission wavelength, 650 to 750 nm). Cell fluorescence was categorized as cytoplasmic (cytoplasmic Gaf1-GFP fluorescence), nuclear-cytoplasmic (Gaf1-GFP fluorescence appearing in the cytoplasm as well as colocalizing with DRAQ5 positive material), or nuclear (Gaf1-GFP fluorescence colocalizing with DRAQ5 positive material). To quantify the intracellular Gaf1-GFP localization, we scored 100 to 200 cells in multiple, randomly chosen fields.

Protein extraction and immunoprecipitation assays.

For Western blot analysis of Gaf1-HA, proteins were extracted with trichloroacetic acid (TCA). For immunoprecipitations (IP) of Gaf1-HA, proteins were extracted with lysis buffer 1 (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 20% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.1% Triton X100, protease inhibitor cocktail, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Cells were broken for 15 min with glass beads and centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000 × g and the supernatant was collected. Approximately 2 mg of proteins was prepared and precleared with 20 µl of a mixture of protein A Sepharose and protein G Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). Two microliters of hemagglutinin (HA) antibodies was added to the cleared extract and incubated overnight at 4°C, followed by addition of 20 µl of a mixture of protein A and G Sepharose beads. After 3 h of incubation, the beads were washed five times with lysis buffer 2 (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 20% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X100). For phosphatase treatment, the beads were diluted with λ-phosphatase reaction buffer and 2 mM MnCl2 and then incubated with 200 U of λ-phosphatase (New England Biolabs) at 30°C for 30 min. The beads were then washed once with lysis buffer 2, resuspended in 25 µl 2× sample buffer, and boiled for 3 min.

Western blotting.

Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE using 12% acrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with 5% milk in TBST before immunoblotting. Detection was carried out using the ECL Super Signal detection system (Thermo Scientific). Gaf1-HA was detected by anti-HA antibodies (Santa Cruz) and tubulin with anti-tubulin antibody (Sigma).

β-Galactosidase assays.

Cells were grown to mid-log phase in minimal medium supplemented with adenine, leucine, and histidine before being harvested and subjected to β-galactosidase assays (27). Error bars in the figures represent standard deviations calculated from three independent cultures.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Cells were grown to log phase, and 100 ml of cultured cells was cross-linked using 1% formaldehyde for 30 min at 30°C. After the addition of 125 mM glycine, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, protease inhibitor cocktail, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Cells were broken with glass beads for 5 min five times, and the beads were washed with lysis buffer. The crude lysate was sonicated (six 10-s pulses at 80% power) with 1 min of incubation on ice between sonications. The supernatant was clarified (2,500 rpm, 30 min). Two microliters of hemagglutinin (HA) antibodies was added to the cleared extract and incubated overnight at 4°C, followed by addition of 20 µl of a mixture of protein A/G Sepharose beads. Before immunoprecipitation with IgG beads, 10% of each sample was removed to be used as a control for the input fraction. After 3 h of incubation, the beads were washed once with lysis buffer, once with lysis buffer containing 360 mM NaCl, once with wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 0.25 M LiCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA) and once with TE buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8], 10 mM EDTA). The beads were resuspended in 0.5 ml elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS). Cross-linking was reversed overnight at 65°C. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated in ethanol for overnight at −20°C. DNA was pelleted for 10 min at 14,000 rpm at 4°C and resuspended in 75 µl of water. Real-time PCR was performed with a Precision Fast qPCR master mix kit (Primer Design). Reactions were performed in triplicate and run on a Step One Plus real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems). Primers that span isp7+ promoter region, including the three GATA motifs, were used. Threshold cycle (CT) values for the DNA of interest were calculated as follows ΔΔCT = (CT input isp7+ − CT input act1+) − (CT IP isp7+ − CT IP act1+). Relative expression levels were calculated as 2ΔΔCT. The level of expression was expressed relative to the expression level of wild-type cells grown in minimal medium (relative value = 1).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Time course analysis of Gaf1-HA electrophoretic mobility upon shift from minimal to no nitrogen or proline medium. Wild-type cells carrying Gaf1-HA were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to no nitrogen or proline for 10 min, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 5 h, and 6 h. Gaf1-HA was detected by anti-HA antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Download

Dephosphorylation and localization of Gaf1 is not affected by Psk1, Sck1, or Sck2. (A and B) Wild-type, Δpsk1, Δsck1 Δsck2, or Δpsk1 Δsck1 Δsck2 cells carrying Gaf1-GFP were grown in minimal medium and shifted to proline (P) for 1 h. Cells were scored for intracellular Gaf1-GFP localization (red, cytoplasmic; yellow, nuclear-cytoplasmic; and green, nuclear). Nuclei were stained with DRAQ5. Cells were visualized by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. Scale bar, 10 µm. (C) Wild-type, Δpsk1, or Δsck1 Δsck2 cells carrying Gaf1-HA were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline for 1 h (P). Gaf1-HA was detected by anti-HA antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Download

Overexpression of ppe1+ or disruption of sds23+ does not affect Gaf1 phosphorylation on minimal medium or after a shift to proline. (A) Wild-type cells transformed with plasmid overexpressing ppe1+ or vector only and also carrying Gaf1-HA at the chromosomal locus were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline (P) for 1 h. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (B) Wild-type cells or Δsds23 mutant cells grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline for 1 h (P). Tubulin was used as a loading control. Download

List of strains used in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Bahler, C. Gancedo, S. Moreno, P. J. Maeng, K. Shiozaki, M. Yamamoto, and M. Yanagida for strains and plasmids. We thank I. Borovok for drawing our attention to the GATA motifs upstream of isp7+ and for valuable discussions, and we thank members of the Kupiec laboratory for encouragement and support.

This research was supported by grants to R.W. from the Association for International Research (AICR) (11-0281), the Israel Science foundation (688/14), and the Open University of Israel (grant no. 31031).

Footnotes

Citation Laor D, Cohen A, Kupiec M, Weisman R. 2015. TORC1 regulates developmental responses to nitrogen stress via regulation of the GATA transcription factor Gaf1. mBio 6(4):e00959-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.00959-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. 2006. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN. 1991. Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science 253:905–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1715094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, Lorberg A, Crespo JL, Bonenfant D, Oppliger W, Jenoe P, Hall MN. 2002. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell 10:457–468. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kupiec M, Weisman R. 2012. TOR links starvation responses to telomere length maintenance. Cell Cycle 11:2268–2271. doi: 10.4161/cc.20401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. 2011. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12:21–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bar-Peled L, Sabatini DM. 2014. Regulation of mTORC1 by amino acids. Trends Cell Biol 24:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weisman R, Cohen A, Gasser SM. 2014. TORC2—a new player in genome stability. EMBO Mol Med 6:995–1002. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201403959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen A, Kupiec M, Weisman R. 2014. Glucose activates TORC2-Gad8 via positive regulation of the cAMP/PKA pathway and negative regulation of the Pmk1-MAPK pathway. J Biol Chem 289:21727–21737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.573824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatano T, Morigasaki S, Tatebe H, Ikeda K, Shiozaki K. 2015. Fission yeast Ryh1 GTPase activates TOR complex 2 in response to glucose. Cell Cycle 14:848–856. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2014.1000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisman R, Choder M. 2001. The fission yeast TOR homolog, tor1+, is required for the response to starvation and other stresses via a conserved serine. J Biol Chem 276:7027–7032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi T, Hatanaka M, Nagao K, Nakaseko Y, Kanoh J, Kokubu A, Ebe M, Yanagida M. 2007. Rapamycin sensitivity of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe tor2 mutant and organization of two highly phosphorylated TOR complexes by specific and common subunits. Genes Cells 12:1357–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuo T, Otsubo Y, Urano J, Tamanoi F, Yamamoto M. 2007. Loss of the TOR kinase Tor2 mimics nitrogen starvation and activates the sexual development pathway in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol 27:3154–3164. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01039-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez B, Moreno S. 2006. Fission yeast Tor2 promotes cell growth and represses cell differentiation. J Cell Sci 119:4475–4485. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urano J, Sato T, Matsuo T, Otsubo Y, Yamamoto M, Tamanoi F. 2007. Point mutations in TOR confer Rheb-independent growth in fission yeast and nutrient-independent mammalian TOR signaling in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:3514–3519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608510104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisman R, Roitburg I, Schonbrun M, Harari R, Kupiec M. 2007. Opposite effects of tor1 and tor2 on nitrogen starvation responses in fission yeast. Genetics 175:1153–1162. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.064170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otsubo Y, Yamashita A, Ohno H, Yamamoto M. 2014. S. pombe TORC1 activates the ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation of the meiotic regulator mei2 in cooperation with Pat1 kinase. J Cell Sci 127:2639–2646. doi: 10.1242/jcs.135517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawai M, Nakashima A, Ueno M, Ushimaru T, Aiba K, Doi H, Uritani M. 2001. Fission yeast tor1 functions in response to various stresses including nitrogen starvation, high osmolarity, and high temperature. Curr Genet 39:166–174. doi: 10.1007/s002940100198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersen J, Nurse P. 2007. TOR signalling regulates mitotic commitment through the stress MAP kinase pathway and the Polo and Cdc2 kinases. Nat Cell Biol 9:1263–1272. doi: 10.1038/ncb1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schonbrun M, Laor D, López-Maury L, Bähler J, Kupiec M, Weisman R. 2009. TOR complex 2 controls gene silencing, telomere length maintenance, and survival under DNA-damaging conditions. Mol Cell Biol 29:4584–4594. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01879-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikai N, Nakazawa N, Hayashi T, Yanagida M. 2011. The reverse, but coordinated, roles of Tor2 (TORC1) and Tor1 (TORC2) kinases for growth, cell cycle and separase-mediated mitosis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Open Biol 1:110007. doi: 10.1098/rsob.110007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weisman R, Roitburg I, Nahari T, Kupiec M. 2005. Regulation of leucine uptake by tor1+ in Schizosaccharomyces pombe is sensitive to rapamycin. Genetics 169:539–550. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saitoh S, Mori A, Uehara L, Masuda F, Soejima S, Yanagida M. 2015. Mechanisms of expression and translocation of major fission yeast glucose transporters regulated by CaMKK/phosphatases, nuclear shuttling and TOR. Mol Biol Cell 26:373–386. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-11-1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schonbrun M, Kolesnikov M, Kupiec M, Weisman R. 2013. TORC2 is required to maintain genome stability during S phase in fission yeast. J Biol Chem 288:19649–19660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.464974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikeda K, Morigasaki S, Tatebe H, Tamanoi F, Shiozaki K. 2008. Fission yeast TOR complex 2 activates the AGC-family Gad8 kinase essential for stress resistance and cell cycle control. Cell Cycle 7:358–364. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.3.5245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuo T, Kubo Y, Watanabe Y, Yamamoto M. 2003. Schizosaccharomyces pombe AGC family kinase Gad8p forms a conserved signaling module with TOR and PDK1-like kinases. EMBO J 22:3073–3083. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weisman R, Choder M, Koltin Y. 1997. Rapamycin specifically interferes with the developmental response of fission yeast to starvation. J Bacteriol 179:6325–6334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laor D, Cohen A, Pasmanik-Chor M, Oron-Karni V, Kupiec M, Weisman R. 2014. Isp7 is a novel regulator of amino acid uptake in the TOR signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol 34:794–806. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01473-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck T, Hall MN. 1999. The TOR signalling pathway controls nuclear localization of nutrient-regulated transcription factors. Nature 402:689–692. doi: 10.1038/45287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunningham TS, Andhare R, Cooper TG. 2000. Nitrogen catabolite repression of DAL80 expression depends on the relative levels of Gat1p and Ure2p production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 275:14408–14414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Georis I, Tate JJ, Cooper TG, Dubois E. 2011. Nitrogen-responsive regulation of GATA protein family activators Gln3 and Gat1 occurs by two distinct pathways, one inhibited by rapamycin and the other by methionine sulfoximine. J Biol Chem 286:44897–44912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.290577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim L, Hoe KL, Yu YM, Yeon JH, Maeng PJ. 2012. The fission yeast GATA factor, Gaf1, modulates sexual development via direct down-regulation of ste11+ expression in response to nitrogen starvation. PLoS One 7:e42409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ter Schure EG, van Riel NA, Verrips CT. 2000. The role of ammonia metabolism in nitrogen catabolite repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Rev 24:67–83. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(99)00030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tate JJ, Georis I, Feller A, Dubois E, Cooper TG. 2009. Rapamycin-induced Gln3 dephosphorylation is insufficient for nuclear localization: Sit4 and PP2A phosphatases are regulated and function differently. J Biol Chem 284:2522–2534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806162200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakashima A, Otsubo Y, Yamashita A, Sato T, Yamamoto M, Tamanoi F. 2012. Psk1, an AGC kinase family member in fission yeast, is directly phosphorylated and controlled by TORC1 and functions as S6 kinase. J Cell Sci 125:5840–5849. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanyu Y, Imai KK, Kawasaki Y, Nakamura T, Nakaseko Y, Nagao K, Kokubu A, Ebe M, Fujisawa A, Hayashi T, Obuse C, Yanagida M. 2009. Schizosaccharomyces pombe cell division cycle under limited glucose requires Ssp1 kinase, the putative CaMKK, and Sds23, a PP2A-related phosphatase inhibitor. Genes Cells 14:539–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper TG. 2002. Transmitting the signal of excess nitrogen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae from the tor proteins to the GATA factors: connecting the dots. FEMS Microbiol Rev 26:223–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoe KL, Won MS, Chung KS, Park SK, Kim DU, Jang YJ, Yoo OJ, Yoo HS. 1998. Molecular cloning of gaf1, a Schizosaccharomyces pombe GATA factor, which can function as a transcriptional activator. Gene 215:319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Won M, Hoe KL, Cho YS, Song KB, Yoo HS. 1999. DNA-induced conformational change of Gaf1, a novel GATA factor in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biochem Cell Biol 77:127–132. doi: 10.1139/o99-022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakashima A, Sato T, Tamanoi F. 2010. Fission yeast TORC1 regulates phosphorylation of ribosomal S6 proteins in response to nutrients and its activity is inhibited by rapamycin. J Cell Sci 123:777–786. doi: 10.1242/jcs.060319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feller A, Georis I, Tate JJ, Cooper TG, Dubois E. 2013. Alterations in the Ure2 alphaCap domain elicit different GATA factor responses to rapamycin treatment and nitrogen limitation. J Biol Chem 288:1841–1855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.385054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bertram PG, Choi JH, Carvalho J, Chan TF, Ai W, Zheng XF. 2002. Convergence of TOR-nitrogen and Snf1-glucose signaling pathways onto Gln3. Mol Cell Biol 22:1246–1252. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1246-1252.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mata J, Lyne R, Burns G, Bähler J. 2002. The transcriptional program of meiosis and sporulation in fission yeast. Nat Genet 32:143–147. doi: 10.1038/ng951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valbuena N, Moreno S. 2012. AMPK phosphorylation by Ssp1 is required for proper sexual differentiation in fission yeast. J Cell Sci 125:2655–2664. doi: 10.1242/jcs.098533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kunitomo H, Higuchi T, Iino Y, Yamamoto M. 2000. A zinc-finger protein, Rst2p, regulates transcription of the fission yeast ste11(+) gene, which encodes a pivotal transcription factor for sexual development. Mol Biol Cell 11:3205–3217. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.9.3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liao WL, Ramón AM, Fonzi WA. 2008. GLN3 encodes a global regulator of nitrogen metabolism and virulence of C. albicans. Fungal Genet Biol 45:514–526. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Umemiya-Shirafuji R, Boldbaatar D, Liao M, Battur B, Rahman MM, Kuboki T, Galay RL, Tanaka T, Fujisaki K. 2012. Target of rapamycin (TOR) controls vitellogenesis via activation of the S6 kinase in the fat body of the tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis. Int J Parasitol 42:991–998. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hansen IA, Attardo GM, Park JH, Peng Q, Raikhel AS. 2004. Target of rapamycin-mediated amino acid signaling in mosquito anautogeny. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:10626–10631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403460101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park JH, Attardo GM, Hansen IA, Raikhel AS. 2006. GATA factor translation is the final downstream step in the amino acid/target-of-rapamycin-mediated vitellogenin gene expression in the anautogenous mosquito Aedes aegypti. J Biol Chem 281:11167–11176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schieber M, Chandel NS. 2014. TOR signaling couples oxygen sensing to lifespan in C. elegans. Cell Rep 9:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weisman R, Finkelstein S, Choder M. 2001. Rapamycin blocks sexual development in fission yeast through inhibition of the cellular function of an FKBP12 homolog. J Biol Chem 276:24736–24742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Longtine MS, McKenzie A III, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953–961. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Time course analysis of Gaf1-HA electrophoretic mobility upon shift from minimal to no nitrogen or proline medium. Wild-type cells carrying Gaf1-HA were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to no nitrogen or proline for 10 min, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 5 h, and 6 h. Gaf1-HA was detected by anti-HA antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Download

Dephosphorylation and localization of Gaf1 is not affected by Psk1, Sck1, or Sck2. (A and B) Wild-type, Δpsk1, Δsck1 Δsck2, or Δpsk1 Δsck1 Δsck2 cells carrying Gaf1-GFP were grown in minimal medium and shifted to proline (P) for 1 h. Cells were scored for intracellular Gaf1-GFP localization (red, cytoplasmic; yellow, nuclear-cytoplasmic; and green, nuclear). Nuclei were stained with DRAQ5. Cells were visualized by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. Scale bar, 10 µm. (C) Wild-type, Δpsk1, or Δsck1 Δsck2 cells carrying Gaf1-HA were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline for 1 h (P). Gaf1-HA was detected by anti-HA antibodies. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Download

Overexpression of ppe1+ or disruption of sds23+ does not affect Gaf1 phosphorylation on minimal medium or after a shift to proline. (A) Wild-type cells transformed with plasmid overexpressing ppe1+ or vector only and also carrying Gaf1-HA at the chromosomal locus were grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline (P) for 1 h. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (B) Wild-type cells or Δsds23 mutant cells grown in minimal medium (M) and shifted to proline for 1 h (P). Tubulin was used as a loading control. Download

List of strains used in this study.