Abstract

Background:

Smoking plays a key role in increasing the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein (CRP).

Aims:

To examine inverse correlation between CRP and magnesium levels in smokers and nonsmokers.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 192 healthy adult male subjects were included in the present study, out of which 96 were smokers and the remaining 96 were nonsmokers having age range from 20 to 40 years, and all the subjects belonged to District Matyari of Hyderabad. Serum CRP was measured by NycoCard standard kit method and magnesium levels by DiaSys standard kit method in smokers and nonsmokers.

Results:

The levels of serum CRP in smokers (14.62 ± 0.16 mg/L) is high as compared to nonsmokers (4.81 ± 0.38 mg/L), which is highly significant (P < 0.001). However, inverse results were seen for serum magnesium levels which were significantly higher (P < 0.001) in nonsmokers (2.52 ± 0.18 mg/L) as compared to the smokers (1.09 ± 0.38 mg/dL). A significant (P < 0.001) inverse relationship between serum CRP and magnesium concentrations were seen in smokers.

Conclusion:

This result shows that smoking increases serum CRP, an inflammatory marker parallel to decrease in serum magnesium levels in smokers having 20-40 years of age.

Keywords: C-reactive protein, Magnesium, Smoking

Introduction

Chronic pulmonary diseases and cardiovascular diseases occur due to cigarette smoking.[1] C-reactive protein (CRP) is an inflammatory marker that raises in inflammation that occurs due to smoking.[2,3] Adipocytes and macrophages release cytokines which radically increases synthesis of CRP.[4,5]

People with increased levels of CRP are on higher risk to develop obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and hypertension.[6,7] It has been experienced that the smoker males had increased levels of serum CRP as compared to nonsmokers.[8] It has been observed that people with altered blood pressure and obesity has affected vascular endothelial function; it occurs due to hypomagnesaemia and increase in plasma levels of CRP in cellular processes.[9,10] Healthy smokers have more insulin resistance which is a characteristics of metabolic syndrome as compared to nonsmokers.

It is also seen that they have also increased glucose levels, decreased high density lipoproteins (HDL) cholesterol, and much more very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) cholesterol. Since these variables are not direct measures of magnesium levels in smokers even then they clearly show that smoking decreases cellular magnesium concentration.[11]

The purpose of present study was to find out the inverse relation between serum levels of CRP and magnesium in smokers.

Systemic acute phase reaction occurs due to inflammation,[12] different studies calculated the level of circulating CRP which shows the severity of inflammation.[13,14,15,16,17] The major initiator, interlukin-6, released by hepatocyte increases the synthesis of CRP in acute phase reactants.[18,19,20,21] CRPs causes neutrophil aggregation and activates tissue factor production. Magnesium intake was inversely associated with plasma CRP concentrations.

Materials and Methods

In this case-control study, we took 192 healthy subjects including 96 smokers and 96 nonsmokers (age range 20-40 years). All subjects belonged to Matyari district of Hyderabad. We assessed serum CRP and magnesium levels in smokers and nonsmokers. These levels were measured to assess the effect of smoking. A written consent was obtained from every subject who was involved in our study before taking blood sample. The ethical approval of the study was granted by the ethical committee. The serum levels for CRP and magnesium were determined by standard methods using NycoCard and DiaSys kits, respectively. We included all the patients, who were smokers but healthy, having no any associated diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obesity, angina, or myocardial infarction.

Spirometry was not done, and we have ruled out any pathology concerned with lungs by history and symptoms, like they have no cough, tuberculosis (TB), or any associated diseases.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was restricted by the number of cases over a period of 18 months, but sample size was not determined. Pearson's correlation was used to determine the possible relation among the variables. Comparisons obtained in present study were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons of mean values between smokers and nonsmokers were done by using Student's t-test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

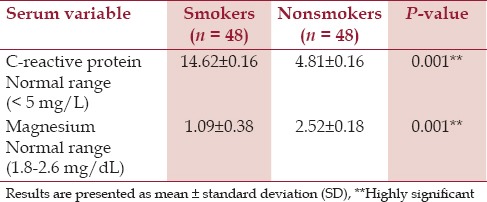

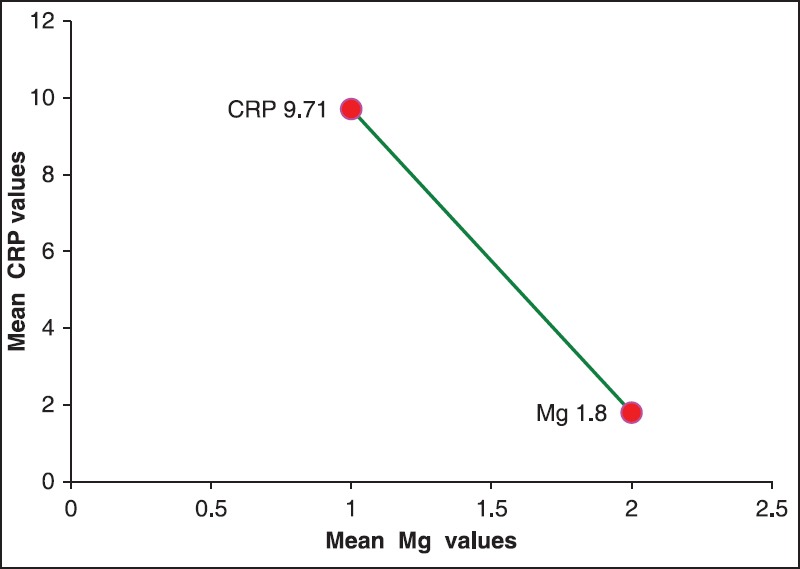

Table 1 shows the inverse relationship between serum CRP and magnesium levels in smokers and nonsmokers. The data shows that the mean serum CRP concentration in smokers (14.62 ± 0.16 mg/L) as against the nonsmokers (4.81 ± 0.38 mg/L) was significantly higher (P < 0.001) [Figures 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Comparison of serum C-reactive protein and magnesium levels between smokers and nonsmokers

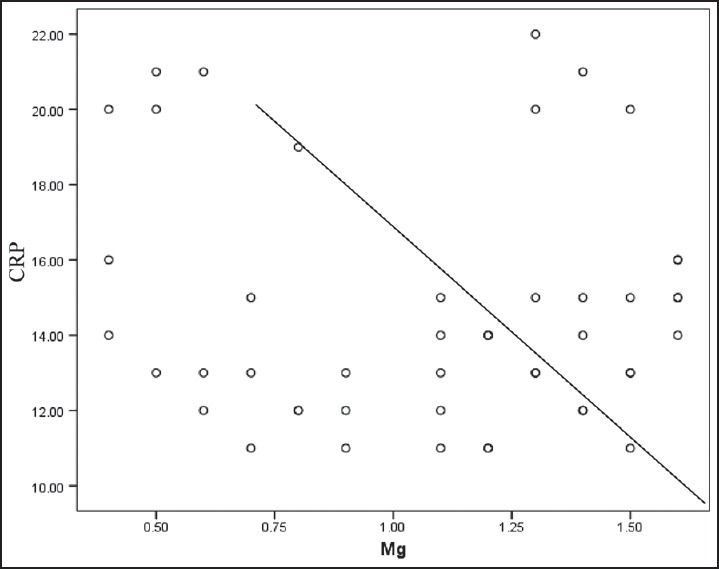

Figure 1.

Correlation between serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and magnesium (Mg) in smokers

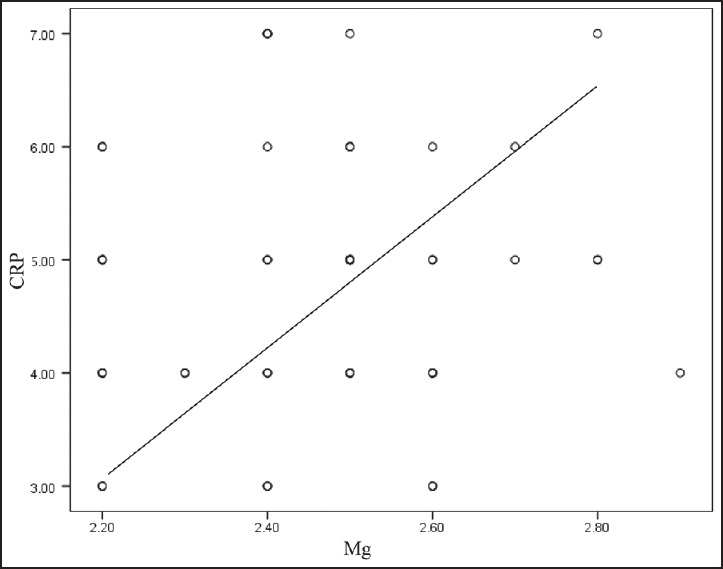

Figure 2.

Correlation between serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and magnesium in nonsmokers

Similarly, the mean serum magnesium concentration in nonsmokers (2.52 ± 0.18 mg/L) compared to smokers (1.09 ± 0.38 mg/L) was significantly higher (P < 0.001). Surprisingly, serum magnesium levels in all smokers were found to be less than 1.8 mg/dL, while serum CRP levels higher than 10 mg/L. On the contrary, all nonsmokers had their serum magnesium concentration greater than 2.0 mg/dL and serum CRP concentrations less than 7.5 mg/L.

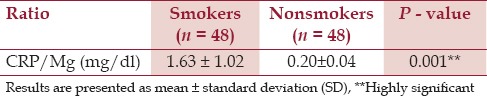

The CRP to magnesium ratio in serum samples of smokers ranged between 0.73 and 5.0 as against 0.12 and 0.29 in nonsmokers, and it was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in smokers as compared to nonsmokers [Table 2]. This difference in the range of ratio clearly shows that decreased serum magnesium levels are independently related to high CRP levels in smokers [Figure 3].

Table 2.

Comparison for C-reactive protein (CRP) to magnesium (Mg) ratio between smokers and nonsmokers

Figure 3.

Correlation between mean levels of serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and magnesium (Mg) in smokers vs nonsmokers

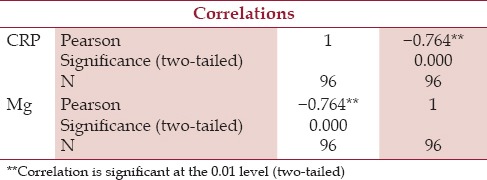

Table 3 shows the analysis of two variables, that is, Mg+2 and CRP are highly negatively related with each other, which means that when one variable increases other will decrease and vice versa, the analysis also shows the strength of relation between two variables. The analysis also shows the strength of the relation between two variables. In this table, the strength is (−0.764), which shows that both variables are strongly negatively related and the results are significant at P < 0.001.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation between serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and magnesium levels in smokers and nonsmokers

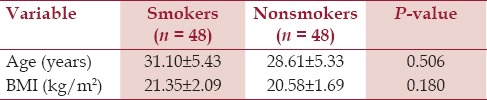

Table 4 shows the normal range of body mass index (BMI) in both cases and control; hence, there is no obesity seen in both the groups.

Table 4.

Comparison of age and body mass index (BMI) between healthy adult male smokers and nonsmokers

Discussion

In our study we have found that there is significantly increased level of serum CRP, which is supported by Das.[2] Malpuech-Brugére et al.,[21] observed the early outcomes of magnesium deficiency in rats during inflammatory response; similarly, the present study also shows the deficiency of magnesium in inflammatory response.

The finding of the present study that smokers have increased level of CRP with decreased level of magnesium is fully supported by Khand et al.[22] Guerrero-Romero et al.,[5] found that activated state of immune cells is the result of hypomagnesemia in nondiabetic, nonhypertensive, obese subjects; this also supports the present study. The study is also supported by that of Dana et al.,[23] that individuals with low intake of magnesium were more likely to have increased CRPs.

The present study clearly demonstrated that smoking significantly decreases serum magnesium concentration and increases serum CRP concentration resulting in an inverse relationship between serum CRP and magnesium concentrations in smokers only. Our study is also justified by the Song et al.,[24] that magnesium intake is inversely related with the CRPs in plasma for the prevalence of metabolic syndrome. According to another study of Mendenhall et al.,[25] smoking, cardiovascular disease, and BMI have a great association with CRPs and we also found similar findings in our results with smoking. Another researcher Tracy et al.,[26] justified our study in way that CRP have an association with the BMI, cardiovascular diseases, and smoking;[26] this study favors our results, but does not explain the inverse relationship between magnesium and CRPs.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the authorities of Isra University for funding this study and also like to acknowledge the students of DUHS, Karachi and staff members for support and the collection of samples. We wish to thank Dr Syed Danish Haseen, Assistant Professor Biochemistry of Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi for his humbleness and greatfulness.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Wannamethee SG, Lowe GD, Shaper AG, Rumley A, Lennon L, Whincup PH. Associations between cigarette smoking, pipe/cigar smoking, and smoking cessation, and haemostatic and inflammatory markers for cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1765–73. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das I. Raised C-reactive protein levels in serum from smokers. Clin Chim Acta. 1985;153:9–13. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(85)90133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–74. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hastie CE, Haw S, Pell JP. Impact of smoking cessation and lifetime exposure on C - reactive protein. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:637–42. doi: 10.1080/14622200801978722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guerrero-Romero F, Rodriguez-Moran M. Relationship between serum magnesium levels and C-reactive protein concentration, in non-diabetic, non-hypertensive obese subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:469–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clyne B, Olshaker JS. The C-reactive protein. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:1019–25. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(99)00135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: A critical update. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1805–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI18921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau DC, Dhillon B, Yan H, Szmitko PE, Verma S. Adipokines: Molecular links between obesity and atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2031–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01058.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Garcia E, Schulze MB, Meigs JB, Manson JE, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, et al. Consumption of trans fatty acids is related to plasma biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. J Nutr. 2005;135:562–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dehghan A, Kardys I, de Maat MP, Uitterlinden AG, Sijbrands EJ, Bootsma AH, et al. Genetic variation, C-reactive protein levels, and incidence of diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:872–8. doi: 10.2337/db06-0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lloyd-Jones DM, Liu K, Tian L, Greenland P. Narrative review: Assessment of C-reactive protein in risk prediction for cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:35–42. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pannen BH, Robotham JL. The acute-phase response. New Horiz. 1995;3:183–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liuzzo G, Biasucci LM, Gallimore JR, Grillo RL, Rebuzzi AG, Pepys MB, et al. The prognostic value of C-reactive protein and serum amyloid a protein in severe unstable angina. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:417–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408183310701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haverkate F, Thompson SG, Pyke SD, Gallimore JR, Pepys MB. Production of C-reactive protein and risk of coronary events in stable and unstable angina. European Concerted Action on Thrombosis and Disabilities Angina Pectoris Study Group. Lancet. 1997;349:462–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07591-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:973–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuller LH, Tracy RP, Shaten J, Meilahn EN. Relation of C-reactive protein and coronary heart disease in the MRFIT nested case-control study. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:537–47. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tracy RP, Lemaitre RN, Psaty BM, Ives DG, Evans RW, Cushman M, et al. Relationship of C-reactive protein to risk of cardiovascular disease in the elderly. Results from the Cardiovascular Health Study and the Rural Health Promotion Project. Arterioscler Throm Vasc Biol. 1997;17:1121–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mestries JC, Kruithof EK, Gascon MP, Herodin F, Agay D, Ythier A. In vivo modulation of coagulation and fibrinolysis by recombinant glycosylated human interleukin-6 in baboons. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1994;5:273–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bataille R, Klein B. C-reactive protein levels as a direct indicator of interleukin-6 levels in humans in vivo. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:982–4. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu ZY, Brailly H, Wijdenes J, Bataille R, Rossi JF, Klein B. Measurement of whole body interleukin-6 (IL-6) production: Prediction of the efficacy of anti-IL-6 treatments. Blood. 1995;86:3123–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malpuech-Brugére C, Nowacki W, Daveau M, Gueux E, Linard C, Rock E, et al. Inflammatory response following acute magnesium deficiency in the rat. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1501:91–8. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khand F, Shaikh SS, Ata MA, Shaikh SS. Evaluation of the effect of smoking on complete blood counts, serum C-reactive proteins and magnesium levels in healthy adult male smokers. J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65:59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dana E, King DE, Arch G. Dietary magnesium and C-reactive protein levels. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24:166–71. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2005.10719461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song Y, Ridker PM, Manson JE, Cook NR, Buring JE, Liu S. Magnesium intake, C-reactive protein, and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and older U. S. women. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1438–44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendenhall MA, Patel P, Ballam L, Strachan D, Northfield TC. C reactive protein and its relationship to cardiovascular risk factors: A population-based cross sectional study. BMJ. 1996;312:1061–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7038.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tracy RP, Psaty BM, Macy E, Bovill EG, Cushman M, Cornell ES, et al. Lifetime smoking exposure affects the association of C-reactive protein with cardiovascular disease risk factors and subclinical disease in healthy elderly subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2167–76. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]