Abstract

Background:

Early cervical spine clearance is extremely important in unconscious trauma patients and may be difficult to achieve in emergency setting.

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to assess the feasibility of standard portable ultrasound in detecting potentially unstable cervical spine injuries in severe traumatic brain injured (TBI) patients during initial resuscitation.

Materials and Methods:

This retro-prospective pilot study carried out over 1-month period (June–July 2013) after approval from the institutional ethics committee. Initially, the technique of cervical ultrasound was standardized by the authors and tested on ten admitted patients of cervical spine injury. To assess feasibility in the emergency setting, three hemodynamically stable pediatric patients (≦18 years) with isolated severe head injury (Glasgow coma scale ≤8) coming to emergency department underwent an ultrasound examination.

Results:

The best window for the cervical spine was through the anterior triangle using the linear array probe (6–13 MHz). In the ten patients with documented cervical spine injury, bilateral facet dislocation at C5–C6 was seen in 4 patients and at C6–C7 was seen in 3 patients. C5 burst fracture was present in one and cervical vertebra (C2) anterolisthesis was seen in one patient. Cervical ultrasound could easily detect fracture lines, canal compromise and ligamental injury in all cases. Ultrasound examination of the cervical spine was possible in the emergency setting, even in unstable patients and could be done without moving the neck.

Conclusions:

Cervical ultrasound may be a useful tool for detecting potentially unstable cervical spine injury in TBI patients, especially those who are hemodynamically unstable.

Keywords: Cervical injury, cervical spine clearance, head injury, ultrasound

Introduction

Almost 8% of all unconscious trauma patients will have a concomitant cervical spine injury.[1] Radiography is not sensitive enough to rule out cervical spine injury, especially as the radiography done in the trauma setting is usually technically unsatisfactory. Patients, therefore, continue to have their cervical spine immobilized in cervical collar till the cervical spine is cleared by computed tomography (CT) spine. Unfortunately, the delay in getting radiology done makes it difficult to conduct various procedures like examination of back, intubation and patient shifting, especially in hemodynamically unstable patients.

If point of care ultrasound can reliably pick up potentially unstable cervical spine fractures, it will cause a paradigm shift in the management of these patients with the potential to revolutionize emergency healthcare for severe head injured patients in most parts of the world. Our study attempts to assess the feasibility of using portable ultrasound in the cervical spine to detect unstable cervical spine injuries in unconscious patients with severe head injury.

Materials and Methods

This retro-prospective pilot study carried out over 1-month period (June–July 2013) after approval from the institutional ethics committee. During the study period, the technique of cervical ultrasound was standardized by the authors and tested on ten admitted patients of cervical spine injury. To assess feasibility in the emergency setting, three hemodynamically stable pediatric patients (≦18 years) with isolated severe head injury (Glasgow coma scale ≤8) coming to emergency department underwent an ultrasound examination. All these patients continued to receive standard management and underwent a head CT with CT cervical spine up to thoracic vertebra (T1). All cervical ultrasound examinations were done by senior author (DA) (without any formal training on ultrasound) on a portable ultrasound machine (MicroMaxx, Sonosite Inc., WA, USA).

Ultrasound technique

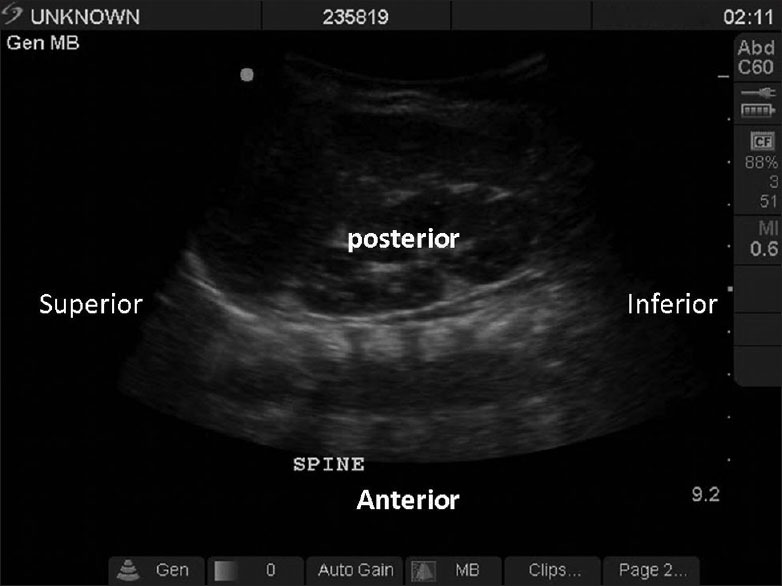

Posterior window

The authors initially performed a sonographic evaluation of the affected region using a high frequency (6–13 MHz) linear array probe placed on the back of the neck of volunteers [Figure 1]. The image quality was excellent with the additional advantage of cervical canal being nicely visible. However, this method is impractical in patients with suspected cervical spine injury as the posterior window is not available to the examiner, except during log-rolling.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound of the cervical spine using the posterior window. The spine is seen best with this window. However, the practical utility is limited in acutely injured patients

Anterior window

Keeping the same linear probe in the anterior triangle of the neck provides satisfactory image quality and allows one to assess the cervical spine from C2 to D1 and see for canal compromise, ligamental injury, and major fractures. [Figures 2 and 3]

Figure 2.

The anatomical landmarks for the anterior window to the cervical spine in the neck. The probe should be kept in the anterior triangle of the neck for optimum resolution

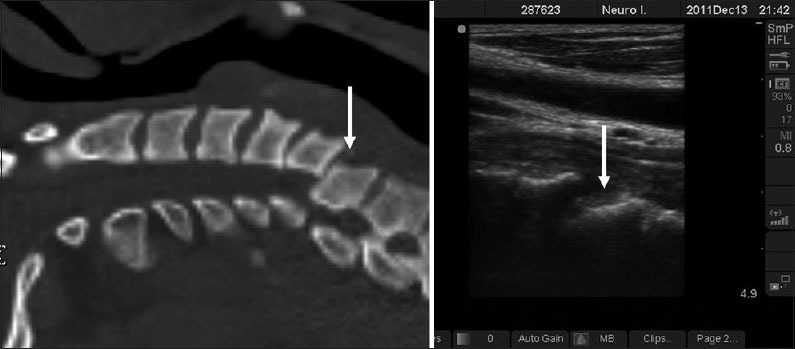

Figure 3.

Computed tomography cervical spine (sagittal section) and ultrasound image of the cervical spine of the same patient shown together for orientation. This figure shows that the cervical spine is very well seen on ultrasound imaging

This window was subsequently used for assessing the cervical spines in admitted patients with known cervical spine injuries. A “potentially unstable cervical spine injury” was defined as any degree of dislocation with loss of continuity of the anterior longitudinal ligament.

Observations

After standardizing the ultrasound technique, ten admitted patients with documented cervical spine injury (on CT cervical spine) were evaluated with the same portable cervical ultrasound. Bilateral facet dislocation at C5–C6 was seen in four patients and at C6–C7 was seen in three patients. C5 burst fracture was present in one and C2 listhesis was seen in one patient. Cervical ultrasound could easily detect fracture lines, canal compromise, and ligamental injury in all cases [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Computed tomography cervical spine (sagittal section) and ultrasound image of the cervical spine of a patient with bilateral facet dislocation at C5–C6. The dislocation and disruption of the anterior longitudinal ligament is the cervical spine, is very well seen on ultrasound imaging (arrow)

Subsequently, three pediatric patients (all males aged 14, 17, and 18 years) with severe head injury underwent ultrasound of the cervical spine in the emergency setting and the ultrasound examination could be done easily without obstructing the ongoing management of the patient (s) [Figure 2]. Cervical spine could be visualized well in all three patients and was normal in all. This was confirmed on subsequent CT of the cervical spine in all cases.

Discussion

Various studies have shown that unconscious trauma patients may have concomitant cervical spine injury with estimates varying from 18% to 26%.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] Furthermore, it has been shown that injury at one level of the spine increases chances of simultaneous injury at other levels manifold.[2] Till date, there is no satisfactory method of picking up “potentially unstable cervical spine injury” in the field or in the emergency department at the time of initial resuscitation. Being portable and commonly used by emergency physicians, ultrasound machines are perfectly suited for mass casualty, low resource, and military applications. However, there have been no studies on the utility of ultrasound in cervical spine clearance in acutely injured patients. If it can be shown that ultrasound can reliably pick up “potentially unstable” cervical spine fractures, it will cause a paradigm shift in the management of these patients. Our study attempts to assess the role and utility of portable ultrasound in assessing the cervical spine of acutely injured patients and correlate with CT of the cervical spine of these patients.

Although, intuitively it appears that ultrasound may not be suited to evaluate the spine, a previous study on horses has described the normal ultrasonographic appearance of the cervical anatomy.[11] In this study, transverse scans were obtained from second (C2) to first T1. Post mortem photographs of frozen cross-sections were obtained as anatomical reference. The authors found that the structures were clearly visualized by ultrasonography and consistency was found between ultrasonographic images and corresponding cross-sectional anatomy. Other studies have attempted to use ultrasound for pedicle screw insertion,[12] and facet injections[13,14] with excellent results.

Our pilot study shows that ultrasound can be used to detect potentially unstable cervical spine injuries like fracture-dislocations. Another important finding of our study was that cervical ultrasound is feasible in the emergency setting and has very high concordance with CT findings for unstable injuries. A very pertinent fact was that all ultrasound examinations were done by a neurosurgeon, and minimal training was required for this level of concordance.

Limitations

Ultrasound being operator dependent, the results can vary depending upon the person doing the scan. However, this holds true for focused abdominal sonography in trauma which has now become the de-facto standard for abdominal trauma.

Furthermore, as the consequences for missing a cervical injury can be disastrous, we recommend that an ultrasound be used only as an adjunct to cervical radiographs/CT cervical spine. However, in low resource settings or in life-threatening situations ultrasound of the cervical spine has the potential to radically improve patient care and allow for early interventions like intubation and transfer of acutely injured patients.

Future directions

Studies on a larger scale are required to validate our findings so as to allow cervical ultrasound for routine clinical use.

Conclusions

Cervical ultrasound is feasible using portable ultrasound machine and by neurosurgeons/emergency physicians with basic training. It holds great potential in resource starved settings and in unstable patients for ruling out unstable cervical spine injuries.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Piatt JH., Jr Detected and overlooked cervical spine injury among comatose trauma patients: From the Pennsylvania Trauma Outcomes Study. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19:E6. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.19.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michael DB, Guyot DR, Darmody WR. Coincidence of head and cervical spine injury. J Neurotrauma. 1989;6:177–89. doi: 10.1089/neu.1989.6.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiu WC, Haan JM, Cushing BM, Kramer ME, Scalea TM. Ligamentous injuries of the cervical spine in unreliable blunt trauma patients: Incidence, evaluation, and outcome. J Trauma. 2001;50:457–63. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200103000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayless P, Ray VG. Incidence of cervical spine injuries in association with blunt head trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7:139–42. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(89)90125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks RA, Willett KM. Evaluation of the Oxford protocol for total spinal clearance in the unconscious trauma patient. J Trauma. 2001;50:862–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200105000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Alise MD, Benzel EC, Hart BL. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of the cervical spine in the comatose or obtunded trauma patient. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:54–9. doi: 10.3171/spi.1999.91.1.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackmore CC, Ramsey SD, Mann FA, Deyo RA. Cervical spine screening with CT in trauma patients: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Radiology. 1999;212:117–25. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.1.r99jl08117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hills MW, Deane SA. Head injury and facial injury: Is there an increased risk of cervical spine injury? J Trauma. 1993;34:549–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brohi K, Healy M, Fotheringham T, Chan O, Aylwin C, Whitley S, et al. Helical computed tomographic scanning for the evaluation of the cervical spine in the unconscious, intubated trauma patient. J Trauma. 2005;58:897–901. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000171984.25699.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holly LT, Kelly DF, Counelis GJ, Blinman T, McArthur DL, Cryer HG. Cervical spine trauma associated with moderate and severe head injury: Incidence, risk factors, and injury characteristics. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:285–91. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.96.3.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg LC, Nielsen JV, Thoefner MB, Thomsen PD. Ultrasonography of the equine cervical region: A descriptive study in eight horses. Equine Vet J. 2003;35:647–55. doi: 10.2746/042516403775696311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kantelhardt SR, Bock HC, Siam L, Larsen J, Burger R, Schillinger W, et al. Intra-osseous ultrasound for pedicle screw positioning in the subaxial cervical spine: An experimental study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010;152:655–61. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0447-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galiano K, Obwegeser AA, Bodner G, Freund MC, Gruber H, Maurer H, et al. Ultrasound-guided facet joint injections in the middle to lower cervical spine: A CT-controlled sonoanatomic study. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:538–43. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000202977.98420.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narouze SN. Ultrasound-guided cervical periradicular injection: Cautious optimism. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006;31:87. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]