Abstract

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is an uncommon multisystem disease with an abnormal polyclonal proliferation of Langerhans cells that invade various organs. In rare instances, the affection of the orbit is the only and the first symptom. We report an unusual case of an 18-month-old male who presented with orbital disease as the first symptom, in the form of chronic presentation of periorbital swelling (2 months duration) with acute inflammation (1-week duration) giving a suspicion of orbital cellulitis. Histopathology after radical excision confirmed the diagnosis of LCH and was advised initial therapy as per Histiocyte Society Evaluation and Treatment Guidelines (2009) but was lost to follow-up only reappearing with progression (multisystem LCH with risk organ involvement) and developed progressive active disease on treatment after 5 weeks. He was treated with salvage therapy for risk patients achieving complete remission.

Keywords: Histiocytosis X, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, orbital disease

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) refers to a group of diseases whose primary pathogenesis is an abnormal polyclonal proliferation of Langerhans cells which invade various organs including skin, bone, liver, spleen, lung, and bone marrow.[1] The clinical presentation depends on the site of involvement usually the head and neck, mainly skull base in 60% cases ranging from a multifocal to a solitary lesion. Orbital involvement occurs in 20–25% cases.[2,3,4] In rare instances, the affection of the orbit is the only and the first symptom of the disease.[5] We report an unusual case of an 18-month-old male who presented with orbital disease as the first symptom.

The main purpose of this case report is that LCH should be considered as one of the possible causes of affections of the orbit in children, in the frequently difficult differential diagnosis of orbital lesions.

Case Report

History

An 18-month-old male, 1st product of a nonconsanguineous marriage presented with progressively increasing right supra-orbital swelling associated with pain of 2 months duration. The patient had skin lesions over the scalp and forehead with loss of appetite since 1 week with no history of otorrhea, fever, weight loss, growth failure, polyuria, polydipsia, dyspnea, and irritability, behavioral and neurological changes.

Examination

On physical examination, the patient had a right supra-orbital swelling, mild right proptosis and a follicular maculopapular rash over the scalp and forehead.

Radiological investigations

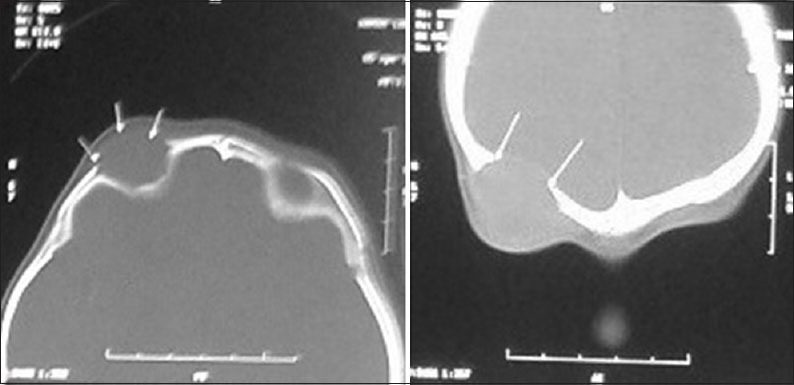

On admission, radiological investigations showed no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly or pulmonary involvement. The computerized tomography (CT) scan of brain showed a 2.1 cm × 2.0 cm well-defined expansile intensely homogenously enhancing mass lesion in the right superolateral orbital rim with breaching of the bony periosteum in the inferior aspect with extraconal orbital spread [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Preoperative computerized tomography brain showing lytic lesions

Operation

Radical excision of the extradural space occupying lesion with granulation tissue above the orbital roof was achieved through a right supra-orbital incision.

Pathology findings

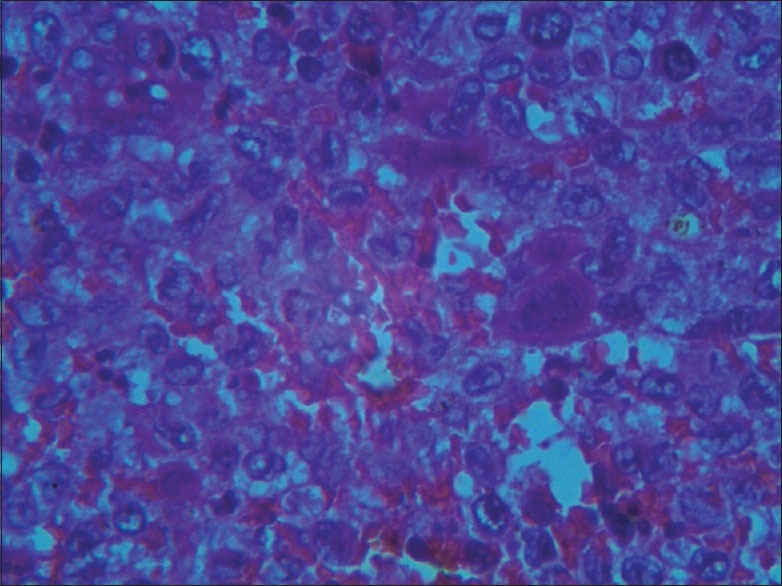

On histopathology, sheets of histiocytic cells with indented pale nuclei with nuclear grooves suggestive of LCH were seen. Positive immunohistochemical staining for S-100 confirmed the diagnosis [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

HPE showing giant cells and Langerhans cells

Postoperative course

We have followed the Histiocyte Society Evaluation and Treatment Guidelines (2009)[3] for managing this patient. Accordingly, the patient was advised initial therapy comprising of a combination of prednisone and vinblastine. However, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Recurrence

The patient was brought to neurosurgical attention 7 weeks after diagnosis with recurrence of the right orbital swelling with intermittent blood tinged nasal discharge of 8 days duration.

Investigations

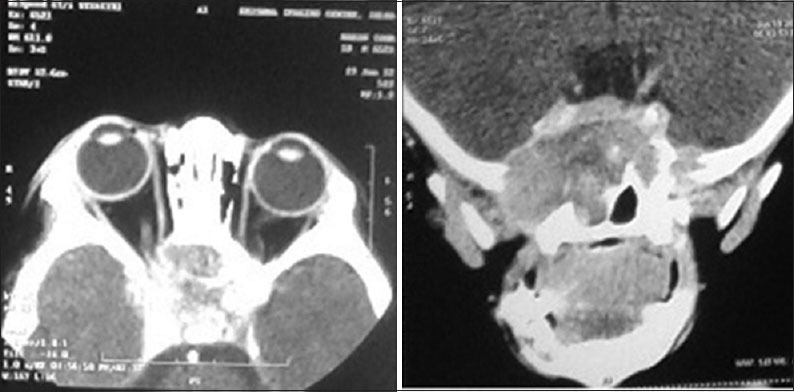

The contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) suggested a large fresh lesion in the sphenoid sinus and the orbital apices more on the right side with lytic destruction of its wall with likely possibility of dural involvement [Figure 3]. The chest X-ray showed diffuse reticular and miliary shadows throughout both lung fields. Bone scan showed no evidence of skeletal involvement. Urine osmolality was 78.61 mosmol/kg that ruled out a possibility of a diabetes insipidus. USG abdomen and pelvis showed mild hepatomegaly. Liver function tests were normal.

Figure 3.

Postoperative computerized tomography brain at 7 weeks showing new lytic lesion in the sphenoid sinus

Patient treatment and response to therapy

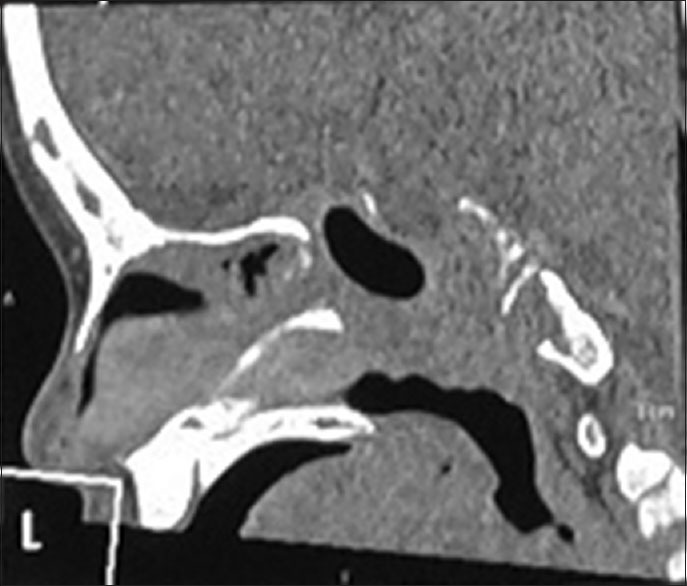

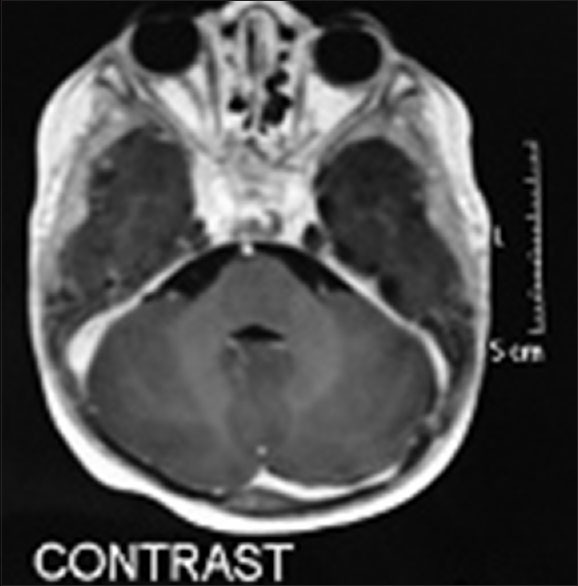

The patient was categorized as multisystem LCH with risk organ involvement and received 4 cycles of chemotherapy with vinblastine and prednisone. To determine response to therapy, CECT was repeated which showed a large destructive lesion involving central skull base, clivus, pituitary fossa, sphenoid sinus with associated well-defined soft tissue enhancing mass in the skull base. There was opacification of the right nasal cavity with the possibility of dural involvement [Figure 4]. Accordingly, a second course treatment with vinblastine and prednisolone and supportive treatment for Pneumocystis carinii and progressive neutropenia were initiated. On follow-up CECT done after 5 weeks, mandibular involvement was noted. The patient was staged as progressive active disease on treatment. Bone marrow study showed no evidence of infiltration. According to the guidelines, salvage therapy for risk patients with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine was initiated. Response to therapy was assessed after 3 cycles that showed regression of the lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain with contrast. Three more cycles were given and MRI done showed disease remission [Figure 5]. The patient is in remission and doing well on follow-up at 4 years.

Figure 4.

Computerized tomography scan after 4 cycles of chemotherapy (progression)

Figure 5.

Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast showing remission

Discussion

Lichtenstein and Jaffe coined the term eosinophilic granuloma in 1940.[1] In 1953, Lichtenstein linked this disease with Hand–Schuller–Christian disease and Letterer–Siwe disease, and proposed to combine these three entities under the name “histiocytosis X,” on the basis of their similar histopathological findings.[6] “LCH” was officially adopted in 1986 during the Workshop on Childhood Histiocytoses.[7] It is still debated whether the proliferation of Langerhans cells is of neoplastic or reactive (e.g., due to viral infection) origin.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a rare disease with incidence approximately 5.4 per million. It has a male predominance mainly affecting children of age between 1 and 4 years.[1] The disease has an unpredictable natural history varying from a rapidly fatal, progressive disease to spontaneous resolution.[1] Three clinical forms of LCH are recognized, namely, Eosinophilic granuloma, Hand–Schuller–Christian disease and Letterer–Siwe disease. Eosinophilic granuloma is characterized by the presence of histiocytic unifocal or multifocal mass lesions that generally originate in the bone. Hand–Schuller–Christian disease manifests as a triad of exophthalmos, bony defects of skull and diabetes insipidus. Letterer–Siwe disease is characterized by widespread soft tissue and visceral involvement with or without bone lesions. It has an acute or subacute course and is sometimes fatal.[3]

Orbital involvement in LCH usually occurs in the chronic multisystem form of the condition that was previously called Hand–Schuller–Christian disease and rarely presents in the acute multisystem variety of Letterer–Siwe disease.[2,3] In one series with only soft tissue involvement, the orbits were not affected, suggesting that they become so from adjacent bony involvement.[3]

The typical ophthalmic presentation is that of a slowly growing upper palpebral temporal swelling with erythema over a period of weeks to months. It can sometimes be confused with periorbital cellulitis. Acute presentation of periorbital swelling caused by LCH is rare and is usually due to the growth of the lesion through the periorbita, inducing an inflammatory response suggesting a clinical diagnosis of dacryoadenitis.[8] As the orbital mass is usually extraconal, and destruction of the orbital walls may result in orbital decompression, only half the patients with orbital involvement develop proptosis.[8] Intracranial LCH may result in papilledema and secondary optic atrophy, with or without the involvement of intraorbital optic nerve and chiasm.[8]

The Histiocyte Society Evaluation and Treatment Guidelines April 2009[3] provides definition of the clinical categories, treatment protocols and assessment of treatment response and response criteria, which can be used for reference.

The prognosis and final outcome depend on several factors such as age of onset, extent of disease, and the presence or absence of organ failure, along with response to therapy. The mortality rate is high in children with the multisystem disease because of failure of key organs such as bone marrow, liver, and lungs.[6] The 5-year survival rate in children under 2 years of age, even with aggressive chemotherapy is only 50%.[8]

Conclusion

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a rare multisystem condition seen commonly in male children of age 1–4 years, with a wide spectrum of presentations. Orbital disease as the first presenting symptom is rare which can mimic common diseases such as periorbital cellulitis, dacryoadenitis that delays accurate diagnosis and treatment of LCH. The 5-year survival rate in children under 2 years of age, even with aggressive chemotherapy is only 50%. It is advisable to have a high index of suspicion and consider LCH as a differential diagnosis of orbital disease in children. An early diagnosis and multidisciplinary approach are required for proper staging of the disease to plan the best management of each case as treatment varies from case to case.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Boston M, Derkay CS. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone and skull base. Am J Otolaryngol. 2002;23:246–8. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2002.123452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucaya J. Histiocytosis X. Am J Dis Child. 1971;121:289–95. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1971.02100150063005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore AT, Pritchard J, Taylor DS. Histiocytosis X: An ophthalmological review. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69:7–14. doi: 10.1136/bjo.69.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sims DG. Histiocytosis X; follow-up of 43 cases. Arch Dis Child. 1977;52:433–40. doi: 10.1136/adc.52.6.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anton M, Holousová M, Rehurek J, Habanec B. Histiocytosis X and the orbit in children. Cesk Oftalmol. 1992;48:176–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis; Histiocyte Society Evaluation and Treatment Guidelines; April. 2009. Available from: http://www.histiocytesociety.org/document.doc?id=290 .

- 7.Chu A, Favara BE, Ladisch S, Nezelof C, Prichard J. Report and recommendations of the workshop on the childhood histiocytoses: Concepts and controversies. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1986;14:116–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y, Fay A. Orbital langerhans cell histiocytosis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2009;49:123–31. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e3181924f9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]