Abstract

Purpose/aim

To investigate the relationship of drusen and photoreceptor abnormalities in African-American (AA) patients with intermediate non-neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Materials and methods

AA patients with intermediate AMD (n=11; ages 52-77 years) were studied with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Macular location and characteristics of large drusen (≥125 μm) were determined. Thickness of photoreceptor laminae was quantified overlying drusen and in other macular regions. A patient with advanced AMD (age 87) was included to illustrate the disease spectrum.

Results

In this AA patient cohort, the spectrum of changes known to occur in AMD, including large drusen, sub-retinal drusenoid deposits and geographic atrophy, were identified. In intermediate AMD eyes (n=17), there were 183 large drusen, the majority of which were pericentral in location. Overlying the drusen there was significant thinning of the photoreceptor outer nuclear layer (termed ONL+) as well as the inner and outer segments (IS+OS). The reductions in IS+OS thickness were directly related to ONL+ thickness. In a fraction (~8%) of paradrusen locations with normal lamination sampled within ~280 μm of peak drusen height, ONL+ was significantly thickened compared to age and retinal-location-matched normal values. Topographical maps of the macula confirmed ONL thickening in regions neighboring and distant to large drusen.

Conclusions

We confirm there is a pericentral distribution of drusen across AA-AMD maculae rather than the central localization in Caucasian AMD. Reductions in the photoreceptor laminae overlying drusen are evident. ONL+ thickening in some macular areas of AA-AMD eyes may be an early phenotypic marker for photoreceptor stress.

Keywords: drusen, optical coherence tomography, photoreceptor outer nuclear layer, African-American age-related macular degeneration

INTRODUCTION

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of irreversible blindness among older persons in Western nations.1,2,3 The non-neovascular or atrophic form of AMD is most common and there are currently no curative options.4,5 Racial differences in prevalence of AMD have been reported in US populations, and African-Americans (AA) have generally had a lower prevalence compared with data on Caucasians.6,7 To date, disease features in AA subjects with AMD have been described using en face fundus imaging and standard grading systems.7,8,9

The microscopic details of AMD are becoming increasingly better understood with the advent of optical coherence tomography (OCT)10. The patterns of photoreceptor loss have been documented in several studies (for example,11,12,13) but quantitation of retinal layers using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) has not previously been reported for AA patients with AMD. In a recent study of a Caucasian (specifically, Amish) population with intermediate AMD, we quantified photoreceptor laminae and showed photoreceptor cell loss and disturbances in the inner and outer segments (IS+OS), as well as an unexpected outer nuclear layer (ONL+) thickening in some patient retinas.13 In the present work we extended this photoreceptor quantitation to the less well-studied AA patients with non-neovascular AMD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Subjects

African-American (AA) patients with a clinical diagnosis of non-neovascular AMD participated in this study. The AREDS classification system14 was used for grading color fundus photos taken at screening sessions, and 17 eyes of 11 patients (age range, 52-77 years; mean±SD, 68±9 years) with intermediate AMD as well as one eye from a patient with advanced AMD (age 87 years) were included. In eyes from intermediate AMD patients, best-corrected visual acuities were 20/25 or better, while in the eye with more advanced disease, visual acuity was 20/63. Spherical equivalent refractive errors ranged from −3.25 to +5.00D. Data from a group of older AA subjects with normal eye examinations (13 eyes of 7 subjects; ages 63-72; mean±SD of 69±3 years) were used to determine retinal structural parameters in healthy eyes. A routine eye examination was performed in all subjects, and ocular and medical histories were obtained. Institutional review board approval and informed consent were obtained, and the procedures adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Some of the results were compared to our previously published13 measurements in a Caucasian population (age range, 53-83 years; mean±SD, 73±7 years). The age ranges of the three populations were frequency matched.

Imaging and Analyses

Cross sectional imaging of the retina was performed with a SD-OCT system (RTVue-100; Optovue Inc., Fremont, CA). To obtain high density coverage of the macula, an acquisition protocol with 4.5 or 9 mm line scans along the horizontal and vertical meridia crossing the fovea, and 6×6 mm raster scans (101 lines with 513 longitudinal reflectivity profiles, LRPs, each) centered at the fovea were used. A confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope was used to perform en face imaging (Spectralis HRA; Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany); specifically, short-wavelength autofluoresence (SW-AF) images were obtained and methods have been published.15

OCT image analyses and segmentation were performed using published methods.13,16,17 In brief, the manufacturer’s software (RTVue-100 ver. 6.1.0.4; Optovue Inc., Fremont, CA) was used to produce an OCT en face projection image and eyes with at least one large (≥125 μm) drusen visible on this image were selected for further analysis. Manual segmentation of retinal layers was performed with the hyposcattering ONL+ layer defined between the hyperscattering outer plexiform layer (OPL) and the hyperscattering outer limiting membrane (OLM). Our OPL/ONL boundary is vitread to the Henle fiber layer (HFL) reflection and our definition of ONL+ thickness includes the anatomical layers of both ONL and HFL.13,18,19 Examples of the OCT segmentation of ONL+ thickness in regions in which HFL visibility varies are provided (Supplemental Figure 1). The IS+OS photoreceptor layer thickness was measured between OLM and the hyperscattering peak near the interface of rod OS tips and apical RPE (retinal pigment epithelium) processes. This region includes the inner segment ellipsoid zone (EZ).20,21 Drusen were defined as being present between the RPE and Bruch’s membrane (BrM). For each large druse, maximum height and width were measured. The retinal location of each druse at peak height was recorded with respect to the location of the fovea in each eye in order to quantify the spatial distribution.

ONL+ and IS+OS thickness were measured at the location of peak drusen height, as well as at a neighboring paradruse location with normal-appearing retinal lamination and no RPE elevation.13 The presence of hyperreflective material in the subretinal space was noted in some of the cross-sectional images and suggested the presence of subretinal drusenoid deposits (SDDs) or pseudodrusen.22,23

Our methods to determine topography of ONL+ thickness across the macula have been published.13 As a screening procedure for photoreceptor abnormalities at a distance from the very central drusen, we quantified ONL+ at the boundaries (16 loci at 3-4.24 mm eccentric to the fovea) of the 6×6 mm macular raster scans in all 17 eyes of the AA-AMD patients and compared the results to normal limits. Based on these screening results, a subset of eyes were chosen for high resolution mapping of ONL+ thickness and thickness difference maps were generated based on the older AA control subjects.

Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and SPSS 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk NY). Interval level measurements were summarized with means while categorical attributes were summarized as percentages. Because multiple drusen were measured in both eyes of many patients, statistical significance was assessed using generalized estimating equations (GEE) methods.24 An exchangeable correlation matrix was assumed and model based standard errors were used. Correlations between interval level variables were summarized with Pearson’s r2, but statistical significance of these relationships was assessed with GEE.

RESULTS

Spectrum of Disease in AA patients with Non-neovascular AMD

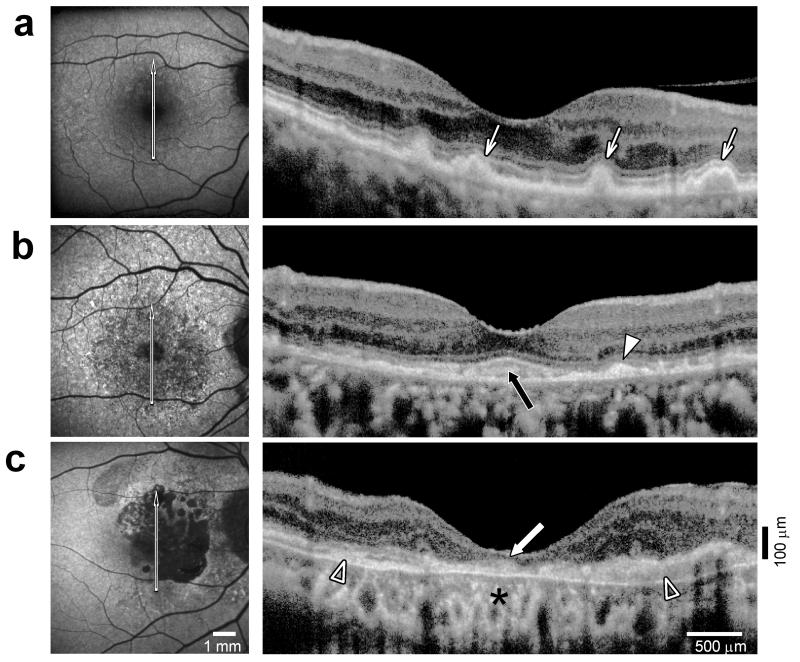

Qualitative observations from autofluorescence images and OCTs indicated a spectrum of severity of disease in our AA patients (Figure 1). All of the features we noted in AA-AMD eyes are well-known to occur in AMD from other populations.25 Drusen were associated with normal autofluorescence, or locally increased or decreased autofluorescence (Figure 1a, left). 26,27,28 Cross sectional images by OCT showed drusen as elevations of the RPE layer (Figure 1a, right). Some eyes showed numerous small patches of increased and decreased autofluorescence (Figure 1b, left) and SDDs (Fig.1b, right) which contrasted to the sub-RPE location of typical drusen. The scan from this AA-AMD patient also shows amorphous-appearing hyperreflective material beneath the foveal region with apparently thinned foveal and surrounding ONL+. The images from one patient are used to exemplify advanced AMD with central geographic atrophy (Figure 1c). The atrophic areas have markedly reduced autofluorescence (Figure 1c). OCT shows increased choroidal reflectivity and disruption of normal retinal laminar architecture with loss of ONL+ in the atrophic region (Figure 1c). Another notable OCT feature in this advanced AMD eye is thickened subretinal material across the central retina (Figure 1c).

FIGURE 1.

Disease spectrum in AA-AMD eyes. (a-c) Short-wavelength autofluorescence (SW-AF, left panel) and OCT scans through the fovea (right panel) in three AA-AMD patients. Arrow on SW-AF image indicates location of OCT scan. (a) A 76-year-old AA patient with intermediate AMD and large drusen shows a minimal change pattern on SW-AF with numerous small patches of slight increases and decreases in intensity. Drusen can be seen on the cross-sectional OCT scan as dome-like elevations of the RPE protruding into adjacent photoreceptor layers (arrows). (b) A 74-year-old AA-AMD patient with subretinal drusenoid deposits (SDD) (as well as large drusen, outside OCT view) displays numerous small patches of substantial increases and decreases in SW-AF. SDD (arrowhead) on OCT scan appear as subretinal deposits above the RPE. Subretinal material under the fovea is also visible (black arrow). (c) An 87-year-old AA patient with advanced AMD and geographic atrophy. Atrophic areas corresponding to severe reductions in SW-AF are surrounded by diffuse patches of increased and decreased autofluorescence. OCT scan demonstrates disruption of laminar architecture, increased choroidal reflectivity (asterisk), loss of photoreceptor layers in the central atrophic region (white arrow), and thickened subretinal material (empty arrowheads). All images are shown as right eyes for ready comparison.

Drusen Distribution in AA-AMD Maculae and Photoreceptor Layer Thickness Overlying the Drusen

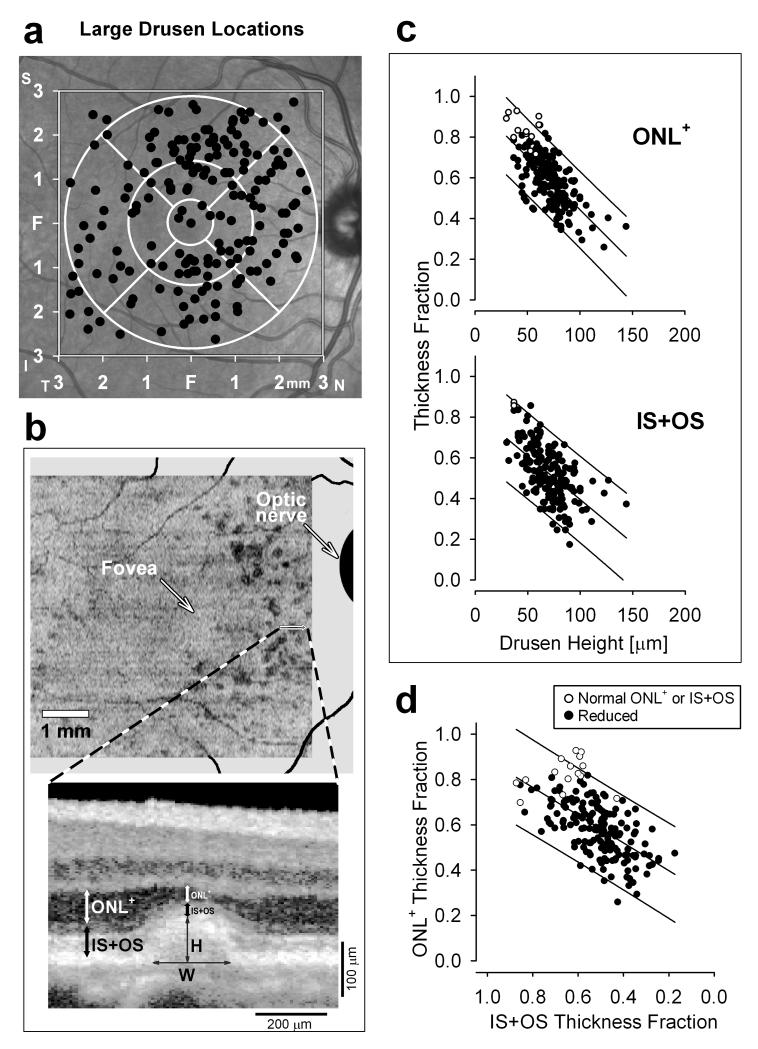

The spatial distribution of the 183 large drusen that we analyzed in the AA-AMD eyes is displayed on an en face image of the fundus (Figure 2a).The majority of these drusen (117/183; 64%) were concentrated in the pericentral zone (the outer circle extending from 1.5 to 3 mm eccentricity). The central zone (foveal circle and surrounding annulus to 1.5 mm eccentricity) showed a lesser drusen concentration (52/183; 28%). This is in contrast to the results from our Amish Causcasian intermediate AMD cohort analyzed with the same methods;13 the Amish patients showed a large drusen concentration in the central zone of 61% while the pericentral zone was 36%. The proportion of drusen classified as central was highly significantly different between the two cohorts (p=0.004, GEE logistic link); including age in the model (p=0.829) did not substantially alter the statistical significance of the difference between cohorts (p=0.005, GEE logistic link). Also different in these two groups of patients classified as intermediate AMD were the widths of drusen. In AA-AMD eyes, drusen width was 263±94 (mean±SD) μm, which was smaller than the average width of drusen (352 ±153 μm) in our Amish AMD cohort.13 This difference was highly statistically significant (p=0.001) even after adjusting for age (p=0.005; GEE identity link). Differences in drusen distribution and drusen width between the two racial groups were not due to differences in drusen load. The average number of drusen per eye (eyes averaged if OD and OS both had drusen) was 9.7 (SD=8.6) in the AA cohort and 11.7 (8.6) in the Amish cohort which was not significantly different (p=0.32, two sample t-test). This difference was even less significant (p=0.73, analysis of covariance) when adjusted for age.

FIGURE 2.

Reduction of photoreceptor layers in intermediate AMD eyes. (a) Spatial distribution of large drusen analyzed (n=183) from all AA-AMD patients in right-eye equivalent representation (filled black circles). In the background is a near-infrared reflectance image for orientation. The 6×6 mm area where measurements were made (square) and the standard Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) grid (white circles) are displayed. F, fovea. (b) En face OCT projection image shows integrated intraretinal backscatter intensity along a ~20 μm slice parallel to BrM. Drusen (darker regions) that were greater than 125 μm wide were analyzed further. Enlarged OCT scan displays sample large drusen microstructure. White and black arrows depict the ONL+ and IS+OS measurements, respectively, at the peak of the druse and at a neighboring paradruse locus. Thin arrows mark the drusen height (H) at peak and horizontal width (W) at the base. (c) ONL+ (upper) and IS+OS (lower) thickness fractions measured above drusen as a function of the maximum height of drusen. Open circles represent results within normal limits, and filled black circles are those with significant reduction. (d) Relationship between ONL+ and IS+OS thickness above drusen. Open circles represent results within normal limits for ONL+ or IS+OS measures. In c and d, lines through data indicate linear regression and 95% prediction intervals.

We quantified the photoreceptor layers in AA-AMD eyes with large drusen (≥125 μm) and no advanced disease features (n=17 eyes) and compared the results to those of a group of older normal AA subjects (n=13 eyes). An en face OCT projection image from the right eye of one of the AA-AMD patients shows drusen (appearing as darker regions) located in the pericentral zone (Figure 2b). A magnified cross-sectional image shows a druse which appears as a dome-like separation of the RPE from BrM. The locations of ONL+ and IS+OS measurements are illustrated; height and width of the druse are also shown (Figure 2b).

There were significant abnormalities in the photoreceptor laminae overlying the large drusen. When the ONL+ thickness measured at the peak height of each druse was compared to location-matched control values, there was significant (>2SD) thinning at 170/183 loci (93%) loci. The average reduction in overlying ONL+ thickness was 41% of the mean normal value. The degree of ONL thickness reduction was strongly related to maximum drusen height (Figure 2c, upper panel; r2=0.49, p<0.001, 53% decrease in ONL per 100 μm increase in drusen height, GEE identity link). These reductions in ONL+ overlying drusen were accompanied by changes in the photoreceptor IS+OS layer. The reduction in IS+OS layer thickness was also strongly related to drusen height (Figure 2c, lower panel; r2=0.34, p<0.001, 45% decrease in IS+OS per 100 μm increase in drusen height, GEE identity link). There was correlation (r2=0.37) between the thickness fractions of ONL+ and IS+OS overlying drusen (Figure 2d). This correlation between thickness fractions was highly statistically significant (p<0.001, GEE identity link). These results were similar to those we found in a Caucasian group of patients with large drusen.13

Photoreceptor Layer Thickening in the AA-AMD Macula

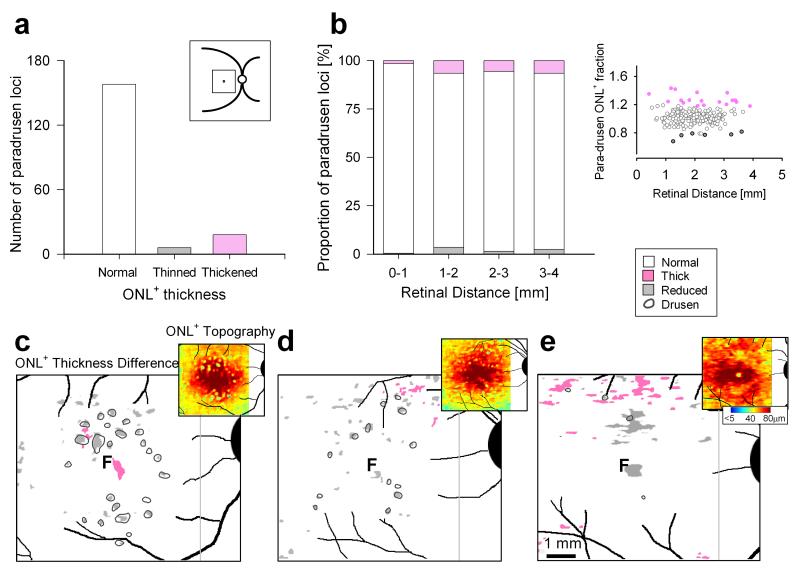

Prompted by our recent finding of regions with increased ONL+ thickness in Caucasians with intermediate AMD,13 we asked whether AA-AMD eyes also had thickened ONL in areas near or distant to drusen. ONL+ thickness was measured in the macula in areas neighboring drusen (described as ‘paradrusen’) with normal-appearing retinal lamination without RPE elevation and as close as possible to previously-identified drusen. These paradrusen measurements were performed similar to the analyses over drusen (Figure 2b). The majority of paradrusen loci (158/182; 87%) showed ONL+ that was within normal limits. At a minority of loci, ONL+ was significantly reduced (6/182; 3%). We also found significant ONL+ thickening in some paradrusen regions (18/182 locations; 10%). Paradrusen locations with thickened, thinned or normal ONL+ were found at all eccentricities measured (Figure 3a,b).

FIGURE 3.

Increased ONL+ thickness in regions neighboring and distant from drusen in AA-AMD eyes. (a) Histograms of the number of paradrusen loci with ONL+ thickness that are within normal limits (n=158), reduced (n=6) and increased (n=18). Inset, schematic representation of the 6×6 mm macular region sampled. (b) Bar graphs representing the proportion of the three categories of paradrusen ONL+ thickness as a function of retinal distance from the fovea. Inset, right, shows paradrusen ONL+ fraction of mean normal thickness as a function of eccentricity. Normal is shown as white, abnormally reduced thickness as gray, and abnormally increased thickness as pink. (c-e) Spatial topography of photoreceptor ONL+ thickness in a 6×6 mm region centered at the fovea of three AA-AMD eyes. Enlarged maps of ONL+ thickness differences are shown for the AA-AMD patients compared with a group of age-matched AA normal subjects. The magnitude of the differences are categorized into three types: locations that are within 2SD of normal variation (white), significantly reduced in thickness (gray, <2SD from mean normal at each locus) and significantly increased in thickness (pink, >2SD). All maps are shown as right eyes for comparability. Insets, upper right, are the pseudocolor maps of ONL+ thickness in these AMD patients sampled at high resolution across the 6×6 mm region centered at the fovea.

We tested the hypothesis that, like intermediate AMD in Caucasian eyes,13 there were regions of thickened ONL+ apart from the paradrusen locations we detected. Three high resolution maps of ONL+ topography were generated (Figure 3c-e); each map is shown as an inset (upper right) to an enlarged difference map that compares the individual patient’s ONL+ to the average normal AA map. A 77-year-old female patient had 24 large drusen; some were in the pericentral region and others more centrally located, with the majority associated with overlying ONL+ thinning (Fig.3c). The difference map confirms the presence of several paradrusen loci with thickened ONL+. A region of ONL+ thickening was also detected in the central zone, at least 400 μm from the closest drusen. A 60-year-old female patient had 13 large drusen and these were located both in the pericentral and central zones. Patchy ONL+ thinning was found and related to the sites of the drusen (Fig.3d). There were only limited sites of paradrusen ONL+ thickening detectable in this patient. A 68-year-old male patient had only 4 large drusen and these were associated with ONL+ thinning. There were some paradrusen areas with ONL+ thickening but more extensive retinal regions (mainly in the superior macula) distant from drusen that showed thickened ONL+ (Fig.3e).

DISCUSSION

OCT Features of AMD in African Americans

Multi-racial population-based studies in the United States have reported that AMD is uncommon among older AA patients compared with Caucasian patients. AA patients were also less likely to develop large drusen, and the very central retina less commonly showed these larger drusen than in Caucasians. This has led to speculation that there may be some unknown mechanism of protection in this central retinal zone of AA patients.6-9 These differences in prevalence and distribution of macular features in AA-AMD compared with Caucasian-AMD were determined from fundus photographs or ophthalmoscopy. Details of the micropathology of AMD in AA patients have not been reported. Among the histopathological studies of AMD (for example,29-35) only a limited number mention post-mortem donor eyes from AA patients.34,35 These studies indicate a lower frequency in AA-AMD compared to AMD in Caucasians, but the full spectrum of degenerative changes associated with AMD were detected in the AA patient eyes.34,35

Cross-sectional high resolution optical imaging has provided us with the opportunity to ask questions about the microscopic disease features in AA-AMD eyes. We first inquired whether the spectrum of OCT micropathology known to occur in Caucasians with AMD was also evident in the AA-AMD patients we sampled. Features such as typical drusen, SDD, and advanced disease characteristics of geographic atrophy were present in AA-AMD. More to our primary purpose, we then focused on drusen and photoreceptor integrity in intermediate AMD. Large drusen locations were determined and, in this cohort of AA-AMD patients, the majority was in the pericentral region. This is in contrast to our observations performed with the same methods in Amish (Caucasian) eyes at the same disease stage. Specifically, the proportion of macular drusen within the central ring was 36% for AA-AMD as compared to 61% for Amish AMD. These observations are concordant with the previous literature that noted a racial difference in presence of drusen in the central zone.6,8

What could be the basis of this racial difference in drusen distribution with increased central zone vulnerability in Caucasian AMD, or central zone protection in AA-AMD? Speculation has included mention of environmental or host exposures, genetic differences in high-risk or protective genes, and the effects of increased melanin in more deeply pigmented eyes. Although there are studies of gene expression in the macula compared to peripheral retina, there have been no data comparing macular regions in human donor eyes of different races.7,36-40

Abnormal Photoreceptor Laminae in Relation to Drusen in African Americans with Intermediate AMD

Concern with photoreceptor integrity in AMD is due to the fact that visual loss is ultimately due to photoreceptor loss. Prevention or delay of photoreceptor loss is the goal of any AMD therapeutic strategy. At least some of this photoreceptor loss relates to abnormalities in and around tissues such as the retinal pigment epithelium and Bruch’s membrane and possibly the choriocapillaris.5 Large drusen, the funduscopic hallmarks of intermediate AMD disease, have been associated with photoreceptor nuclear and outer segment abnormalities by histopathological and optical imaging studies.11,13,25,30,33 Drusen that are large, soft and confluent are considered as risk factors for progression to advanced AMD, although the exact natural history of drusen is not completely understood.41-43 The natural history of photoreceptor loss as related to drusen is also not clear but quantitation of the relationship with drusen is a first step and should be followed by serial studies that are now possible with non-invasive cross sectional imaging. Also required for larger studies are evaluation of intra- and inter-observer reliability and repeatability of the manual segmentation of retinal layer thicknesses.

The current work demonstrates that the relationship of drusen to photoreceptor laminar thickness abnormalities in AA-AMD eyes is similar to that in the Caucasian AMD eyes we previously studied.13 The pathogenic process that relates drusen and photoreceptor loss would appear to be no different between these two racial groups, but serial quantitative observations in these groups should determine if the similarity extends to time course of disease progression. With the prevalence of AMD among African-American populations reported to be lower than in Caucasians, especially advanced disease,6,8,44,45 serial studies should decide if the time course is simply more prolonged or the previous observations are due a central retinal vulnerability of Caucasians and the central protection in AA-AMD as suggested by drusen distribution.

Increased Photoreceptor Nuclear Layer Thickness in African-American AMD

This is the second study to report thickening of the ONL+ in AMD, the first being our previous measurements indicating ONL+ thickening in an Amish Caucasian group with intermediate AMD.13 The basis of the results remains unknown. One hypothesis is that this may be an early surrogate marker for photoreceptor stress. There has been documentation of photoreceptor nuclear layer thickening in pre-degenerate retinal regions in animal models of hereditary retinal degenerations.46,47 There could be an increase in levels of growth factors released in response to cell death in AMD. Growth factor release has been shown to increase ONL thickness by increasing the number of outer nuclear cells (for example, 48,49), cell nuclear size,48-50 as well as intercellular space.48 Increased retinal and ONL thickness have been reported in response to ciliary neurotrophic factor intraocular implants in clinical trials.51,52 ONL+ thickening could relate to the HFL component of the measurement and be partly due to photoreceptor axonal swelling. Muller glial reaction can also occur in response to a variety of retinal insults including neuronal loss due to laser injury53 as well as early degenerative retinal stress in human retinal degenerations.54,55 Muller glia can proliferate, hypertrophy, and migrate in response to growth factors53,56 and lead to retinal or ONL thickening.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 1. OCT segmentation of ONL+ thickness in regions where Henle fiber layer (HFL) visibility varies. (a, c) Vertical OCT scans through the fovea with varying entry position of OCT beam through the pupil in a 70-year-old normal AA subject (a), and a 28-year-old normal Caucasian subject (c). The reflectivity signal originating from the HFL can be seen to differ for each subject based on varying beam entry position for each scan. In panel a, the HFL contribution in the inferior retina is less prominent in the upper scan (a1) and more prominent in the lower scan (a2). In panel c, HFL contribution is again less prominent in the upper scan (c1) than in the lower scan (c2). Longitudinal reflectivity profiles (LRP) corresponding to the dashed boxes demonstrate quantitatively the reflectivity changes associated with the HFL prominence (b,d). Segmentation of the ONL+ is achieved by placing the sclerad boundary immediately vitread to the outer limiting membrane (OLM) peak where the maximum of the local slope is reached. The vitread ONL+ boundary is placed immediately sclerad to the outer plexiform layer (OPL) peak that is closest to the hyposcattering inner nuclear layer (INL). This segmentation results in similar measurements of ONL+ thickness independent of the prominence of the HFL.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health to the University of Pennsylvania, Macula Vision Research Foundation, NEI/NIH R01 EY017549, and the Foundation Fighting Blindness. AVC is a RPB Senior Scientific Investigator.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman DS, O’Colmain BJ, Muñoz B, Tomany SC, McCarty C, de Jong PT, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:564–572. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erke MG, Bertelsen G, Peto T, Sjølie AK, Lindekleiv H, Njølstad I. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in elderly Caucasians: the Tromsø Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1737–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein R, Klein BE. The prevalence of age-related eye diseases and visual impairment in aging: current estimates. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:ORSF5–ORSF13. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gehrs KM, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, Hageman GS. Age-related macular degeneration--emerging pathogenetic and therapeutic concepts. Ann Med. 2006;38:450–471. doi: 10.1080/07853890600946724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman HR, Chan CC, Ferris FL, 3rd, Chew EY. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet. 2008;372:1835–1845. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61759-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman DS, Katz J, Bressler NM, Rahmani B, Tielsch JM. Racial differences in the prevalence of age-related macular degeneration: The Baltimore Eye Survey. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein R, Chou CF, Klein BE, Zhang X, Meuer SM, Saaddine JB. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:75–80. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bressler SB, Munoz B, Solomon SD, West SK, Salisbury Eye Evaluation (SEE) Study Team Racial differences in the prevalence of age-related macular degeneration: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation (SEE) Project. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:241–245. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang MA, Bressler SB, Munoz B, West SK. Racial differences and other risk factors for incidence and progression of age-related macular degeneration: Salisbury Eye Evaluation (SEE) Project. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2395–2402. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farsiu S, Chiu SJ, O’Connell RV, Folgar FA, Yuan E, Izatt JA, et al. Quantitative classification of eyes with and without intermediate age-related macular degeneration using optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuman SG, Koreishi AF, Farsiu S, Jung SH, Izatt JA, Toth CA. Photoreceptor layer thinning over drusen in eyes with age-related macular degeneration imaged in vivo with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartmann KI, Gomez ML, Bartsch DU, Schuster AK, Freeman WR. Effect of change in drusen evolution on photoreceptor inner segment/outer segment junction. Retina. 2012;32:1492–1499. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318242b949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadigh S, Cideciyan AV, Sumaroka A, Huang WC, Luo X, Swider M, et al. Abnormal thickening as well as thinning of the photoreceptor layer in intermediate age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:1603–1612. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group The Age-Related Eye Disease Study system for classifying age-related macular degeneration from stereoscopic color fundus photographs: AREDS report No. 6. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:668–681. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cideciyan AV, Swider M, Aleman TS, Roman MI, Sumaroka A, Schwartz SB, Stone EM, Jacobson SG. Reduced-illuminance autofluorescence imaging in ABCA4-associated retinal degenerations. J Opt Soc Am A. 2007;24:1457–1467. doi: 10.1364/josaa.24.001457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Gibbs D, Sumaroka A, Roman AJ, Aleman TS, et al. Retinal disease course in Usher syndrome 1B due to MYO7A mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:7924–7936. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Peshenko IV, Sumaroka A, Olshevskaya EV, Cao L, et al. Determining consequences of retinal membrane guanylyl cyclase (RetGC1) deficiency in human Leber congenital amaurosis en route to therapy: residual cone-photoreceptor vision correlates with biochemical properties of the mutants. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:168–183. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curcio CA, Messinger JD, Sloan KR, Mitra A, McGwin G, Spaide RF. Human chorioretinal layer thicknesses measured in macula-wide, high-resolution histologic sections. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3943–3954. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lujan BJ, Roorda A, Knighton RW, Carroll J. Revealing Henle’s fiber layer using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1486–1492. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spaide RF, Curcio CA. Anatomical correlates to the bands seen in the outer retina by optical coherence tomography: literature review and model. Retina. 2011;31:1609–1619. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182247535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spaide RF. Questioning optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2203–2204.e. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zweifel SA, Imamura Y, Spaide TC, Fujiwara T, Spaide RF. Prevalence and significance of subretinal drusenoid deposits (reticular pseudodrusen) in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1775–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curcio CA, Messinger JD, Sloan KR, McQwin G, Medeiros NE, Spaide RF. Subertinal drusenoid deposits in non-neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2013;33:265–276. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31827e25e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanlehy JA, Negassa A, deB Edwardes MD, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiology. 2003;157(4):364–375. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keane PA, Patel PJ, Liakopoulos S, Huessen FM, Sadda SR, Tufail A. Evaluation of age-related macular degeneration with optical coherence tomography. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:389–414. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delori FC, Fleckner MR, Goger DG, Weiter JJ, Dorey CK. Autofluorescence distribution associated with drusen in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:496–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forte R, Querques G, Querques L, Massamba N, Le Tien V, Souied EH. Multimodal imaging of dry age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90:e281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujimura S, Ueta T, Takahashi H, Obata R, Smith RT, Yanagi Y. Characteristics of fundus autofluorescence and drusen in the fellow eyes of Japanese patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2363-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarks JP, Sarks SH, Killingsworth MC. Evolution of soft drusen in age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Lond) 1994;8:269–283. doi: 10.1038/eye.1994.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curcio CA, Medeiros NE, Millican CL. Photoreceptor loss in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1236–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kliffen M, van der Schaft TL, Mooy CM, de Jong PT. Morphologic changes in age-related maculopathy. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;36:106–122. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970115)36:2<106::AID-JEMT4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarks SH, Arnold JJ, Killingsworth MC, Sarks JP. Early drusen formation in the normal and aging eye and their relation to age related maculopathy: a clinicopathological study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:358–368. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.3.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson PT, Lewis GP, Talaga KC, Brown MN, Kappel PJ, Fisher SK, et al. Drusen-associated degeneration in the retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4481–4488. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green WR, Key SN., 3rd Senile macular degeneration: a histopathologic study. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1977;75:180–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green WR, Enger C. Age-related macular degeneration histopathologic studies. The 1992 Lorenz E. Zimmerman Lecture. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1519–1535. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu DN, Simon JD, Sarna T. Role of ocular melanin in ophthalmic physiology and pathology. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:639–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holliday EG, Smith AV, Cornes BK, Buitendijk GH, Jensen RA, Sim X, et al. Insights into the genetic architecture of early stage age-related macular degeneration: a genome-wide association study meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharon D, Blackshaw S, Cepko CL, Dryja TP. Profile of the genes expressed in the human peripheral retina, macula, and retinal pigment epithelium determined through serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:315–320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012582799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowes Rickman C, Ebright JN, Zavodni ZJ, Yu L, Wang T, Daiger SP, et al. Defining the human macula transcriptome and candidate retinal disease genes using EyeSAGE. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2305–2316. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radeke MJ, Peterson KE, Johnson LV, Anderson DH. Disease susceptibility of the human macula: differential gene transcription in the retinal pigmented epithelium/choroid. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:366–380. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gass JD. Drusen and disciform macular detachment and degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;90:206–217. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1973.01000050208006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bressler NM, Munoz B, Maguire MG, Vitale SE, Schein OD, Taylor HR, et al. Five-year incidence and disappearance of drusen and retinal pigment epithelial abnormalities. Waterman study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:301–308. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100030055022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yehoshua Z, Wang F, Rosenfeld PJ, Penha FM, Feuer WJ, Gregori G. Natural history of drusen morphology in age-related macular degeneration using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2434–2441. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pieramici DJ, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Schachat AP. Choroidal neovascularization in black patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:1043–1046. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090200049020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schachat AP, Hyman L, Leske MC, Connell AM, Wu SY, The Barbados Eye Study Group Features of age-related macular degeneration in a black population. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:728–735. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100060054032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beltran WA, Wen R, Acland GM, Aguirre GD. Intravitreal injection of ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) causes peripheral remodeling and does not prevent photoreceptor loss in canine RPGR mutant retina. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:753–771. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beltran WA, Acland GM, Aguirre GD. Age-dependent disease expression determines remodeling of the retinal mosaic in carriers of RPGR exon ORF15 mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3985–3995. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bok D, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, Ruiz A, Duncan JL, Chappelow AV, et al. Effects of adeno-associated virus-vectored ciliary neurotrophic factor on retinal structure and function in mice with a P216L rds/peripherin mutation. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74:719–735. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeiss CJ, Allore HG, Towle V, Tao W. CNTF induces dose-dependent alterations in retinal morphology in normal and rcd-1 canine retina. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bush RA, Lei B, Tao W, Raz D, Chan CC, Cox TA, et al. Encapsulated cell-based intraocular delivery of ciliary neurotrophic factor in normal rabbit: dose-dependent effects on ERG and retinal histology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2420–2430. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Talcott KE, Ratnam K, Sundquist SM, Lucero AS, Lujan BJ, Tao W, et al. Longitudinal study of the cone photoreceptors during retinal degeneration and in response to ciliary neurotrophic factor treatment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2219–2226. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birch DG, Weleber RG, Duncan JL, Jaffe GJ, Tao W, Cilliary Neurotrophic Factor Retinitis Pigmentosa Study Groups Randomized trial of cilliary neurotrophic factor delivered by encapsulated cell intraocular implants for retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tackenberg MA, Tucker BA, Swift JS, Jiang C, Redenti S, Greenberg KP, et al. Muller cell activation, proliferation and migration following laser injury. Mol Vis. 2009;15:1886–1896. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV. Treatment possibilities for retinitis pigmentosa. N Eng J Med. 2010;363:1669–1671. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1007685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cideciyan AV, Rachel RA, Aleman TS, Swider M, Schwartz SB, Sumaroka A, et al. Cone photoreceptors are the main targets for gene therapy of NPHP5 (IQCB1) or NPHP6 (CEP290) blindness: generation of an all-cone Nphp6 hypomorph mouse that mimics the human retinal ciliopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1411–1423. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang SS, Li H, Huang P, Lou LX, Fu XY, Barnstable CJ. MAPK signaling during Müller glial cell development in retina explant cultures. J Ocul Biol Dis Infor. 2010;3:129–133. doi: 10.1007/s12177-011-9064-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 1. OCT segmentation of ONL+ thickness in regions where Henle fiber layer (HFL) visibility varies. (a, c) Vertical OCT scans through the fovea with varying entry position of OCT beam through the pupil in a 70-year-old normal AA subject (a), and a 28-year-old normal Caucasian subject (c). The reflectivity signal originating from the HFL can be seen to differ for each subject based on varying beam entry position for each scan. In panel a, the HFL contribution in the inferior retina is less prominent in the upper scan (a1) and more prominent in the lower scan (a2). In panel c, HFL contribution is again less prominent in the upper scan (c1) than in the lower scan (c2). Longitudinal reflectivity profiles (LRP) corresponding to the dashed boxes demonstrate quantitatively the reflectivity changes associated with the HFL prominence (b,d). Segmentation of the ONL+ is achieved by placing the sclerad boundary immediately vitread to the outer limiting membrane (OLM) peak where the maximum of the local slope is reached. The vitread ONL+ boundary is placed immediately sclerad to the outer plexiform layer (OPL) peak that is closest to the hyposcattering inner nuclear layer (INL). This segmentation results in similar measurements of ONL+ thickness independent of the prominence of the HFL.