Abstract

Only 17% of Miami-Dade County residents are African American, yet this population accounts for 59% of the county’s HIV-related mortality. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend annual testing for persons at increased risk for HIV, but 40% of African Americans have never been tested. OraQuick®, the first FDA-approved home-based HIV rapid test (HBHRT), has the potential to increase testing rates; however, there are concerns about HBHRT in vulnerable populations. We conducted focus groups in an underserved Miami neighborhood to obtain community input regarding HBHRT as a potential mechanism to increase HIV testing in African Americans. We queried HIV knowledge, attitudes toward research, and preferred intervention methods. Several HIV misconceptions were identified and participants expressed support for HIV research and introducing HBHRT into the community by culturally appropriate individuals trained to provide support. We concluded that community health workers paired with HBHRT were a promising strategy to increase HIV testing in this population.

Keywords: African Americans, community health workers (CHW), focus groups, HIV, HIV rapid testing

HIV rates in Miami, Florida, are more than double the national rates, and Miami-Dade County has the highest HIV rate per capita in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011). Over the past 2 decades, widespread adoption of HIV testing and advances in therapeutic treatment have significantly extended the life span of people living with HIV (PLWH) and reduced HIV-related mortality (Rubin, Colen, & Link, 2010). Despite progress, the HIV-related death rate in Miami is four times the national average (Miami-Dade County Health Department, 2012; Murphy, Xu, & Kochanek, 2013). This elevated mortality rate suggests that HIV testing and access to treatment is not occurring early enough to achieve optimal outcomes.

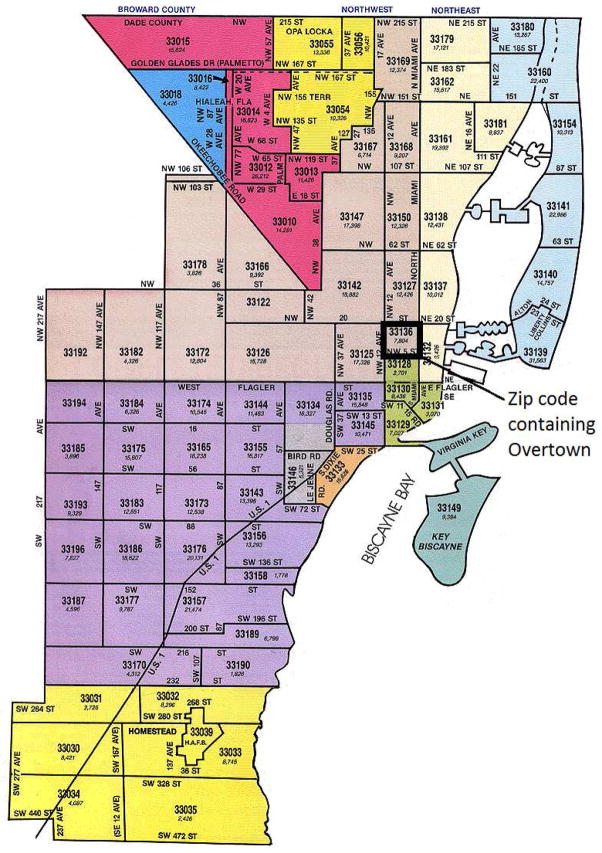

Within the county, the burden of HIV is unequal, and Miami experiences some of the largest racial disparities in HIV in the entire United States (Miami-Dade County Health Department, 2013). Although only 17% of the Miami-Dade population is African American, they account for 59% of HIV-related deaths (Miami-Dade County Health Department, 2013). Geographically, the burden of HIV is concentrated within certain African American communities. One of these highly vulnerable communities is Overtown, a predominantly African American neighborhood where 53% of residents live below the poverty level (City-Data.com, 2011). Overtown’s location within Miami-Dade is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Miami-Dade county zip code map: Location of Overtown.

Note. Image source: Realprogroup.com. (2011). Miami-Dade County Zip Code Map. Retrieved from http://www.realprogroup.com/pages/Miami-Dade.html

Although 3 out of 5 African Americans nationwide have been tested for HIV, this population suffers from the worst HIV outcomes (CDC, 2010). Thus, the CDC (2010) recommends annual testing for adults in high-risk communities. Although two clinic-based testing sites exist in Overtown, key informant interviews with the testing staff revealed that fewer than 10 individuals have been tested per month at these sites.

Community-based, on-site HIV rapid testing has been shown to significantly increase testing in communities highly impacted by HIV in multiple populations around the world (Metsch et al., 2012; Sullivan, Lansky, & Drake, 2004). A recent development in HIV rapid testing has been the FDA approval of OraQuick®, a commercially sold home-based HIV rapid testing (HBHRT) kit. Evaluation of home-based HIV testing in developing countries shows that it leads to higher uptake in testing compared to clinic-based testing (Baiden et al., 2007; Helleringer, Kohler, Frimpong, & Mkandawire, 2009; Nelson et al., 2012). Despite its benefits and potential to increase HIV testing, there are several concerns related to this approach (Bateganya, Abdulwadud, & Kiene, 2010; Pai & Klein, 2008; Paltiel & Walensky, 2012). Although the kit can be purchased at any major pharmacy for about $50, the acceptability of this testing approach in highly vulnerable communities has not been explored (Pai, 2007). In addition to cost, testing without pre- and post-test counseling and lack of referral to relevant HIV care is a potential major limitation of HBHRT (Pai & Klein, 2008; Paltiel & Walensky, 2012). This concern is especially accentuated in high-risk populations that lack experience interacting effectively with health care systems. To our knowledge, there are no studies on the acceptability of HBHRT by African Americans in vulnerable communities.

We describe here a formative study that was conducted prior to a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to test the feasibility of HBHRT in an underserved, predominantly African American community. The goal of our research was to obtain community input about the feasibility and acceptability of a potential HBHRT intervention and to conduct four focus groups with residents of Overtown, our target neighborhood. We were specifically interested in (a) identifying HIV knowledge gaps that should be considered in developing an effective HBHRT testing strategy for Overtown, and (b) determining a method that would likely be accepted by the target population. For example, it was important to gauge whether the population would prefer to complete testing with a lay person from a similar cultural background or with a clinician specifically trained in HIV treatment. We present qualitative data that was generated in focus groups and used to develop a culturally tailored, HBHRT investigation in Overtown.

Methods

Community Wellness Coalition

Our research approach was informed by community-based participatory research (CBPR) strategies (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 2001). CBPR invites community participation throughout the research process and has recently emerged as an important method to help investigators develop an understanding of cultural and social norms regarding disease prevention in underserved populations. In the Overtown community, our CBPR efforts were governed by the Community Wellness Coalition (CWC), a private-public-academic partnership that was founded in 2010 by the study Principal Investigator (PI) and several community members who lead community-based organizations in the target neighborhood. CWC supports community-based initiatives designed to improve health outcomes, education opportunities, and quality of life in Overtown. The partnership involves the active participation of community leaders from Overtown, as well as an interprofessional team of students and investigators from the University of Miami. The priorities of the CWC are determined through meetings between community members and academic partners. During these meetings, which occur every 8–12 weeks, pressing health issues and potential services to address the issues are discussed. In the past, the CWC has provided community health assessments, wellness workshops to raise awareness about specific health conditions and to link residents to appropriate services, aerobics classes at the women’s shelter, and a free mental and physical health screening clinic at the Overtown Youth Center. The ultimate goal for CWC is to provide the collective expertise and resources needed to maximize the impact of service programs and philanthropic gifts that target the wellness needs of culturally distinct Miami communities.

The PI developed our study in response to community feedback regarding high rates of HIV infection and low rates of testing due to limited access to anonymous testing facilities, and stigma associated with utilizing the mobile HIV testing van, which community members identified as the most accessible testing resource in Overtown. In the early phases of study development, CWC members determined that the Health Belief Model was an appropriate framework for conducting formative research (Hayden, 2013). During CWC meetings regarding our study, both the lack of knowledge about HIV risk and the limited access to publicly funded HIV care were identified as potential contributors to low testing rates and, ultimately, to poor HIV outcomes in the target population. Thus, the focus group guide developed for the study incorporated HIV education about HIV risk, testing options, therapeutic advances that have improved HIV outcomes, and accessible health care coverage available to PLWH. The education was delivered in brief intervals during each discussion, as outlined by the guide. As per the Health Belief Model, individuals are more likely to proceed with a behavior if they feel capable of doing it (Hayden, 2013). The education aspects of the focus groups were, therefore, designed to help participants learn about various testing mechanisms and access to follow-up care that could support optimal outcomes, regardless of financial situation.

Specific focus group questions were determined by reviewing published surveys on HIV research in minority populations and discussing these survey questions with established HIV disparities researchers from the University of Miami, community leaders, and residents from Overtown. In adherence with community-based participatory research strategies, all questions and potential response options used as probes to generate dialogue were discussed with community residents at community-based events prior to the study and their feedback was incorporated into the final focus group questions and structure of the questions. The institutional review board at the University of Miami approved this study.

Community Health Workers

Community health workers (CHWs) are respected lay members of the target community. CHWs are especially trained to use community-based strategies to help their peers improve specific health outcomes (Bhutta, Lassi, Pariyo, & Huicho, 2010). In our study, a team of all female CHWs and the PI (also female) were responsible for recruiting study participants, facilitating focus groups (led by the PI), and capturing data during the focus groups via audio recording and handwritten observations. In addition to their active participation in the CWC, the CHWs also completed training provided by the Miami-Dade Department of Health and the Area Health Education Center. CHW training occurred over 3 weeks and addressed multiple issues, including HIV disease progression, pre- and post-test counseling strategies, and accessing HIV care via the public health system.

Participant Recruitment

Criteria for participation in our study were as follows: adults ages 18–60 years, residents of Overtown, willing to participate, English proficiency, and HIV uninfected or unknown HIV status. Participants were recruited through CWC existing community-based partnerships. CHWs disseminated fliers to community stakeholders and provided their contact information to anyone who was identified as a potentially eligible participant. In addition, CHWs attended community events where they engaged potential participants and described intended study activities. To determine eligibility, CHWs screened all potential participants with an IRB-approved brief questionnaire that queried race, city of residence, HIV status, and, if applicable, date of last HIV text. Following screening, eligible participants were informed of the time, date, and location of their respective focus groups.

Focus Groups

In June and July 2013, four focus groups were conducted in community-based locations in Overtown, including a women’s shelter, a recreational center, and a youth center. These locations were selected because they were centrally located in the target neighborhood, accessible by public transportation, and employees at these locations were members of the CWC. Each focus group was coordinated by CHWs and community members who worked at the respective locations and who were present during each focus group. To decrease potential discomfort when broaching the topics of sex and HIV, each group was gender specific. Two sessions were conducted with a total of 19 females; the other two focus groups included a total of 8 males. Upon arrival, each participant received an informed consent form, an audio/visual consent form, and a demographic assessment. The focus group moderator read these documents aloud to participants to ensure complete understanding. Once participants completed the informed consent process, the documents were collected and the focus groups formally began. Prior to beginning each focus group, participants were informed that the study team had received a grant to test the feasibility of home-based rapid HIV testing and the focus group feedback would help determine specific methods to deliver an intervention that would be acceptable to the community. A digital voice recorder was used to capture audio content in each session. We used an IRB-approved focus group guide designed to generate discussions on HIV transmission knowledge (i.e., Has anyone ever told you that certain behaviors, such as not using a condom during sexual intercourse, increased your risk for contracting HIV? If yes, who?); perceptions toward HIV testing (i.e., What do you think African Americans need to know about HIV rapid testing?); and attitudes toward HIV research (i.e., What are your thoughts about HIV-related studies?). The focus group guide also incorporated brief education segments at designated points during the discussion. The education was designed to improve knowledge of HIV testing, HIV transmission behaviors, clinical advances in HIV treatment, and the Ryan White Care Act for PLWH. Each focus group lasted 60 to 90 minutes. Audio recording was stopped at the end of each focus group, and participants received a $20 gift card to compensate participants for their time. All recordings were transcribed within 24 hours of completion. A doctorally-prepared qualitative analysis consultant who was recommended by the biostatistics core at the University of Miami then formally analyzed the transcripts.

Data Analysis

The external qualitative consultant who performed the analysis specialized in community-based research and was initially sought based on advice from a senior-level HIV researcher who mentored the study PI. The qualitative analysis consultant reviewed the transcripts of each focus group, provided a general summary, identified recurring themes that emerged throughout all of the focus groups, and coded the transcripts according to these themes. To ensure accuracy of the report submitted by the consultant, the PI and CHWs reviewed and compared the report to the focus group transcripts. The PI also discussed the report with the CHWs and community members who helped facilitate the focus groups. The PI, CHWs, and analyst discussed differences in interpretation of data until a consensus was achieved. In addition, the actual focus group transcripts were referred to several times while drafting this manuscript and quotes from participants were extracted directly from the transcripts. As described in the introduction, our research is a sub-study within a larger project that examined the feasibility and acceptability of HBHRT in underserved African American communities. The results collected in this formative study were used during the design and implementation stages of the follow-up RCT.

Results

Demographics

The demographics of the sample are reported in Table 1. Twenty-seven adults in Overtown, between 18 and 59 years of age, participated in the focus groups. Most (89%) identified as Black and females accounted for 70% of the sample. Almost three quarters (74%) completed high school and the majority had monthly incomes of $500 or less. More than half (56%) of the population were single and identified their religion as Baptist (63%).

Table 1.

Demographics

| N = 27 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| • Male | 8 | 29.6 |

| • Female | 19 | 70.4 |

| How would you describe your race? | ||

| • White | 3 | 11.1 |

| • Black | 22 | 81.5 |

| • Mixed | 2 | 7.4 |

| Are you Hispanic or Latino? | ||

| • Yes | 3 | 11.1 |

| • No | 24 | 88.9 |

| Age (years) | ||

| • 18 – 29 | 10 | 37 |

| • 30 – 39 | 2 | 7.4 |

| • 40 – 49 | 6 | 22.2 |

| • 50 – 59 | 9 | 33.3 |

| What is the highest level of education you completed? | ||

| • 5th grade or less | 1 | 3.7 |

| • 9th grade to 11th grade | 9 | 33.3 |

| • High school graduate or GED | 10 | 37 |

| • 2 years of college/AA degree Technical school training | 5 | 18.5 |

| • College graduate (BA or BS) | 2 | 7.4 |

| About how much money do you get in 1 month? | ||

| • Less than $500 | 18 | 66.7 |

| • $500 – $1000 | 7 | 25.9 |

| • More than $2000 | 1 | 3.7 |

| • Did not respond | 1 | 3.7 |

| Marital Status | ||

| • Single/Never married | 15 | 55.6 |

| • Living with partner | 3 | 11.1 |

| • Married | 1 | 3.7 |

| • Separated | 2 | 7.4 |

| • Divorced | 6 | 22.2 |

| Employment Status | ||

| • Employed/Self-Employed | 9 | 33.3 |

| • Homemaker | 1 | 3.7 |

| • Unemployed/not working | 15 | 55.6 |

| • Unknown/Not Applicable | 2 | 7.4 |

| Do you consider yourself religious | ||

| • Yes | 23 | 85.2 |

| • No | 4 | 14.8 |

| What is your religion? | ||

| • Catholic | 1 | 3.7 |

| • Protestant | 1 | 3.7 |

| • Baptist | 17 | 63 |

| • Other | 5 | 18.5 |

| • Did not respond | 3 | 11.1 |

Focus Group Outcomes

Three major themes emerged from the focus groups: (a) HIV misconceptions, (b) support for HIV testing, and (c) willingness to participate in HIV research.

HIV misconceptions

Although participants displayed an understanding that risky behaviors, such as having sex without a condom, increased the likelihood of contracting HIV, many did not know that treatments were available to extend the lives of PLWH. Very few participants understood the difference between HIV and AIDS. In addition, participants displayed no knowledge of the Ryan White Care Act, which is available to support health care and medications for all PLWH in the United States. A recurrent misconception that was discussed in every focus group was that the “carrier” lives longer, but the “victims” they infect die quickly. As one male participant stated, “I heard that the carrier lives longer (with HIV) and the people they spread it to die quicker.”

Other HIV misconceptions were based on assumptions about racial/ethnic background, willingness to engage in sex shortly after meeting a potential partner, and condom use. Participants assumed that people were HIV infected if they wanted to have sex immediately, or if they were unwilling to use a condom. One male said, “There are some women who will throw themselves on you and those are the ones that I’m worried about.” In addition, a female participant expressed,

These guys don’t even know you and they’ll tell you they love you and try to sleep with you, especially the Haitians. They say, “Hey baby, I love you” and I’m like, “You don’t even know me!” Then I just ask, “Okay then – where’s the condom?” and they say, “Oh no, I don’t need one.” Then I know they got that thing.

Support for HIV testing

The majority of participants were very supportive of HIV testing. One woman said, “I think HIV testing should be mandatory.” Two male participants suggested that we should work with community churches to conduct testing. “What about St. John’s Church? That would be a good place to put testing. They also feed the homeless over there.” When asked, Has anyone ever talked to you about HIV testing?, most participants indicated that a physician or health care worker had discussed HIV testing with them and one female stated that she learned about testing from an HIV testing and case management agency (Empower U) that came to her church. Most indicated that they get tested regularly. A male participant stated, “I get tested every 6 months at the nearest clinic for safety purposes so I don’t put other people at risk.” Participants from a female group made statements such as, “I get tested every 90 days for HIV,” and “My (former) PE coach told me to get tested, so I did.” Although most had previous successful experiences with HIV testing, one participant, who described herself as a lesbian, felt that she was forced to overcome multiple barriers to get an HIV test. “They said since I had not been with men, I didn’t need to be tested, but they don’t know what I‘ve been doing or who I’ve been with.”

Although most supported HIV testing, participants conveyed considerable apprehension about the OraQuick® Home test. The major concern was learning about being HIV infected without the support of medical personnel who could help facilitate treatment. There were also concerns about individuals not reporting their HIV infection to the health department. A female participant stated, “The thing is if they go home alone and they take that test alone in their house – they’re not gonna’ report it. And no official knows it. Their main concern would be to keep it on the down low.” Participants were much more receptive to the idea of receiving CHW assistance to complete the test and provide pre- and post-test counseling as well as assistance to access HIV care. One female stated, “If I was diagnosed, I would really need some support. I need to know how to live with it.”

Although several participants identified the benefits of having a CHW come to their home to assist with Oraquick®, many described fear that a CHW arriving to their home would cause suspicion from neighbors and become a potential threat to privacy. A female participant remarked,

The thing with [the CHW] is that if you got someone with a briefcase looking professional – there are nosey people – and they will notice something. Unless you send someone that looks like they’re from the community then everyone will notice.

However, most felt that CHW-assisted HBHRT could provide the necessary support to complete an HIV test and, if positive, successfully access HIV care. A male participant stated, “Bringing it to the people is the best thing you can do.”

Willingness to participate in HIV research

The study population was familiar with research and the majority had positive reactions toward studies or had participated in research before. Overall, participants expressed the importance of research studies. A female participant stated, “At the end of the day, 2 or 3 years from now, someone will be helped because of it.” A male participant showed his support by stating, “ Without research, there’s no cure.” When asked specifically about HIV research with minorities, a female responded, “We just need more research to be done. Maybe you can organize a group for support to see that there are a lot of people living with the disease.”

Participants also indicated knowledge that dishonesty can easily distort results. One woman admitted to enrolling in a smoking cessation study even though she was not a smoker, while another woman expressed reservations with research stating that, “[The researchers] can skew the data.”

Participants believed that HIV-related research was a source of empowerment and education. One female explained that, through research, she learned about the risk factors associated with sex without a condom. The majority of participants agreed that more people should participate in HIV specific studies. One woman proclaimed, “Because they can be empowered by it.” In terms of a method for conducting an HBHRT study in Overtown, participants discussed the importance of having culturally representative community members as part of the study team. One female participant stated that the PI and research assistants on the study, “Didn’t look broke-down enough to be trusted by the community.” Another male participant highlighted the importance of having a man on the team, “Because men need to talk to someone who looks like them. They might get tested by the women, but it will be for the wrong reasons.”

Discussion

Our study was conducted to obtain community input about the feasibility and acceptability of a potential HBHRT intervention. Our data indicated that a HBHRT intervention that incorporated CHW support could be a promising strategy to increase HIV testing rates in vulnerable African Americans in Overtown and similar communities. We found that participant motivation to complete an HBRHT was influenced by whether they would receive assistance in taking the test and, if needed, accessing care. The major concerns expressed about conducting HBHRT independently were centered on inability to obtain health care after a positive diagnosis. Although our study was one of the first pilot investigations examining home-based rapid HIV testing in the United States, the views expressed during focus groups were consistent with research done in several African countries and in Peru. These studies showed that HBHRT was an acceptable method of testing in communities with an elevated HIV risk and more likely to be completed than clinic-based testing (Baiden et al., 2007; Helleringer et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 2012). To our knowledge, this is the first study that explores the feasibility of HBHRT led by CHWs in a high-risk urban African American community.

Similar outcomes were observed in studies of other ethnic minority groups in the United States. Seña, Hammer, Wilson, Zeveloff, and Gamble (2010) conducted door-to-door HIV rapid testing outreach in areas of predominantly Latino immigrants, using Latino CHWs in Durham, North Carolina. The community members were not only accepting of HIV rapid testing in the community, but an overwhelming majority preferred it to clinic-based testing (Seña et al., 2010).

Data on individual perceptions, modifying factors, and likelihood of completing an HIV test were consistent with the Health Belief Model (Hayden, 2013). Our participants believed that if residents in the community understood their increased risk for HIV transmission and had enough HIV knowledge to understand treatment options, including accessible health insurance for PLWH, testing rates would improve in Overtown. Aligned with the self-efficacy tenet of the Health Belief Model, people will not proceed with a new behavior unless they believe that they are capable of doing it (Hayden, 2013). Participants in our study expressed that CHW-assisted HBHRT would provide enough support to enable completing an HIV test and, if positive, successful linkage to appropriate care. This reflected the concerns participants expressed regarding taking the test alone and their preferences for CHW assistance in completing HBHRT. This finding was critically important and added to the growing body of data suggesting that inability to successfully access HIV care was a major contributor to poor outcomes in African Americans (Del Rio, 2012; Havlir & Beyrer, 2012). Many reported that they had recently completed an HIV test and identified sources to inform them of accessible testing options. However, others described poor outcomes, including death, in HIV-infected individuals with whom they had personal contact. These stimuli served as cues to action that motivated individuals to get tested. Our research indicated that offering HBHRT paired with CHWs in high-risk African American communities might be a promising alternative to clinic-based HIV testing. The goals set forth by the U.S. National HIV/AIDS Strategy focused on increased HIV testing so more people could access early care and reduce transmission risk (U,S, Department of Health and human Services, 2010). Our results show that HBHRT has the potential to advance these goals among African Americans.

Our research also identified misconceptions about HIV transmission and health care options. Participants were unaware that HIV is a manageable disease rather than a fatal diagnosis. There was also no knowledge of the Ryan White Care Act, which facilitates access to HIV care and medications. Erroneous information may serve as a barrier to HIV testing and should be considered when developing HIV interventions in this community.

It is important to note that the retail price for Oraquick® is approximately 50 USD. As the majority of participants reported $500 or less as monthly earnings, this price accounts for approximately 10% of their monthly income. It would be worthwhile for future studies to examine whether cost is a barrier for introducing HBHRT into communities with limited resources.

The small sample size, the limited geographical area where study activities were conducted, and the qualitative study design limited our study. Therefore, our results should not be generalized to other populations.

In addition, due to budgeting limitations, the PI was involved in some of the preliminary recruitment activities and coordination of focus groups. As she had an extensive history of conducting HIV research, advocacy, and testing initiatives in this community, she had earned the trust of many key leaders and stakeholders in the neighborhood. This factor may have influenced participant willingness to engage in HIV research and report routine HIV testing. Future programs using a similar method would benefit from acknowledging and discussing the potential impact that relationships between study staff and community members may have on participation and outcomes. This is especially important when determining the generalizability of study findings. It must be noted that more than one community member was initially identified to lead the focus groups; however, these individuals were unable to complete the University’s rigorous hiring process within the designated time frame allocated for the study and, thus, the PI stepped in to lead the groups. Future efforts to conduct CBPR studies should explore alternate methods of incorporating community members into the compensated study staff, such as sub-contracting with community agencies that have more flexible hiring processes.

The convenience sampling method used to recruit participants resulted in more female than male participants. This gender imbalance was likely associated with the fact that, in general, women participate in research more often than men (Dunn, Jordan, Lacey, Shapley, & Jinks, 2004). It may also have been influenced by the gender composition of our study staff, which was predominantly female. To overcome the challenge of recruiting males and females equally, we recommend that CHWs of both sexes be involved during recruitment and implementation of research activities. In addition, we recommend that focus groups be facilitated by someone of the same gender as the participants. It is possible that some important information was not discussed during the male-only focus groups because a female led them. Given the high incidence of HIV in this community, and the underutilization of existing HIV testing facilities in the area, the high rates of recent HIV testing reported by participants was unexpected. However, the data were useful and HIV testing within the prior 12 months was added as an exclusion criterion in the follow-up RCT. Although the neighborhood was predominantly African American, 11% of our sample did not identify as African American. Thus, in the follow-up investigation, only those who identified as African American were included in the study population.

Conclusions

Gauging best practices for conducting studies is necessary to implement effective outreach in distinct communities. The qualitative data collected in our study was used to determine whether an HBHRT intervention could be a feasible intervention in Overtown and to identify culturally acceptable strategies of implementation. Our research yielded essential information regarding HIV-related knowledge gaps in the target community and led to the development of a culturally tailored RCT investigation testing CHW-led HBHRT in Overtown.

With regard to acceptability and feasibility, the follow-up RCT was modified as a direct result of the study findings described herein. To ensure that individuals outside of our target group were not represented in the study, eligible participants of the follow-up RCT were required to be African American and to have not completed an HIV test within the prior 12 months. To improve acceptability of this approach to potential male participants, CHWs of both genders conducted informal HIV awareness activities at community-based locations, such as the local church, which provided free food to community members. In response to participant information regarding the need for support throughout HBHRT, the follow-up RCT relied on CHWs to engage participants from pre-baseline until post-study. During these activities, potential participants expressed interest in the study directly to CHWs, who immediately screened and, when appropriate, completed the informed consent process with eligible participants. Following informed consent, CHWs individually contacted participants in person or via phone to inform them of their group assignment and to schedule a time to facilitate HBHRT or deliver HBHRT to those assigned to the control condition. This strategy was highly acceptable and allowed for the active phase of the follow-up RCT to be completed within 1 month. Our ultimate goal was to determine the most effective methods to improve HIV testing rates among African Americans in high-risk communities. Our results suggest that, if tailored appropriately, a CHW-led HBHRT initiative could be a promising approach to increase HIV testing among African Americans in Overtown and similarly underserved communities.

Key Considerations.

Rapid HIV testing facilitated by community health workers (CHWs) may increase HIV testing rates among African Americans in culturally distinct neighborhoods.

The decision to take an HIV test may be influenced by post-diagnosis CHW support to access HIV care.

Misconceptions about HIV transmission, HIV treatment, and access to HIV care were common among residents of an underserved community. HIV education delivered by CHWs was an acceptable strategy to improve HIV knowledge and screening behaviors.

To reach both men and women, it is critical for community-based HIV interventions to be delivered by culturally representative individuals who represent both genders.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant Number 1UL1TR000460, Miami Clinical and Translational Science Institute, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We would like to thank Saliha Nelson and Candice Anderson from Urgent, Inc. for allowing our team to conduct research in their space. We are most grateful to Rai Johnson from Lotus House Shelter and Emanuel Washington, Sr., from the Overtown Optimists for facilitating participation in focus groups.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sonjia Kenya, Assistant Professor, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA.

Ikenna Okoro, Study Coordinator, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA.

Kiera Wallace, Research Assistant, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA.

Olveen Carrasquillo, Chief of the Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA.

Guillermo Prado, Professor, University of Miami School of Nursing and Health Studies, Miami, Florida, USA.

References

- Baiden F, Akanlu G, Hodgson A, Akweongo P, Debpuur C, Binka F. Using lay counsellors to promote community-based voluntary counselling and HIV testing in rural northern Ghana: A baseline survey on community acceptance and stigma. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2007;39(5):721–733. doi: 10.1017/S0021932006001829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateganya M, Abdulwadud OA, Kiene SM. Home-based HIV voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) for improving uptake of HIV testing. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;(7):CD006493. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006493.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta AZ, Lassi ZS, Pariyo G, Huicho L. Global experience of community health workers for delivery of health related millennium development goals: A systematic review, country case studies, and recommendations for integration into national health systems. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/publications/CHW_FullReport_2010.pdf?ua=1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2011. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: HIV testing and diagnosis among adults—United States, 2001–2009. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5947a3.htm.

- City-Data.com. Demographics of Overtown. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.city-data.com/neighborhood/Overtown-Miami-FL.html.

- Del Rio C. The cascade of HIV care in the US. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.jwatch.org/ac201209100000009/2012/09/10/cascade-hiv-care-us.

- Dunn K, Jordan K, Lacey R, Shapley M, Jinks C. Patterns of consent in epidemiologic research: Evidence from over 25,000 responders. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159(11):1087–1094. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlir D, Beyrer C. The beginning of the end of AIDS? New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:685–687. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1207138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden JA. Introduction to health behavior theory. 2. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Helleringer S, Kohler HP, Frimpong JA, Mkandawire J. Increasing uptake of HIV testing and counseling among the poorest in sub-Saharan countries through home-based service provision. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;51(2):185–193. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819c1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Community-based participatory research: Policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Education for Health. 2001;14(2):182–197. doi: 10.1080/13576280110051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miami-Dade County Health Department. Florida Department of Health in Miami-Dade County number of resident HIV deaths and rates 2002–2012. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.dadehealth.org/downloads/Deaths%202012%20Miami-Dade.pdf.

- Miami-Dade County Health Department. HIV among Blacks or African-Americans. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.dadehealth.org/downloads/FS-MDC_BlackS_2013-B.pdf.

- Metsch LR, Feaster DJ, Gooden L, Matheson T, Mandler RN, Haynes L, Colfax GN. Implementing rapid HIV testing with or without risk-reduction counseling in drug treatment centers: Results of a randomized trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(6):1160–1167. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: Final data for 2010: National vital statistics reports. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_04.pdf. [PubMed]

- Nelson AK, Caldas A, Sebastian JL, Munoz M, Bonilla C, Yamanija J, Shin S. Community-based rapid oral human immunodeficiency virus testing for tuberculosis patients in Lima, Peru. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2012;87(3):399–406. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai NP. Oral fluid-based rapid HIV testing: Issues, challenges and research directions. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. 2007;7(4):325–328. doi: 10.1586/14737159.7.4.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai NP, Klein MB. Are we ready for home-based, self-testing for HIV? Future HIV Therapy. 2008;2(6):515–520. [Google Scholar]

- Paltiel AD, Walensky RP. Home HIV testing: Good news but not a game changer. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;157(10):744–746. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin MS, Colen CG, Link BG. Examination of inequalities in HIV/AIDS mortality in the United States from a fundamental cause perspective. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(6):1053–1059. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seña AC, Hammer JP, Wilson K, Zeveloff A, Gamble J. Feasibility and acceptability of door-to-door rapid HIV testing among Latino immigrants and their HIV risk factors in North Carolina. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010;24(3):165–173. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Lansky A, Drake A. Failure to return for HIV test results among persons at high risk for HIV infection: Results from a multistate interview project. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2004;35(5):511–518. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S, Department of Health and Human Services. National HIV/AIDS Strategy. 2010 Retrieved from https://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/overview/