In March, 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) was signed into law by President Obama. The law has been controversial, to say the least. Both political parties believe that it is one of the most important pieces of social legislation to have been enacted in several decades, but they look at this law through decidedly different lenses. The same can be said of scholars and think tanks on the left and on the right. What are the fundamental differences between these contrasting views? In October 2011, 19 months after passage of the law, a conference — The Health Care Reform Law (PPACA): Controversies in Ethics and Policy — was held at the Medical University of South Carolina to explore some of those differences.

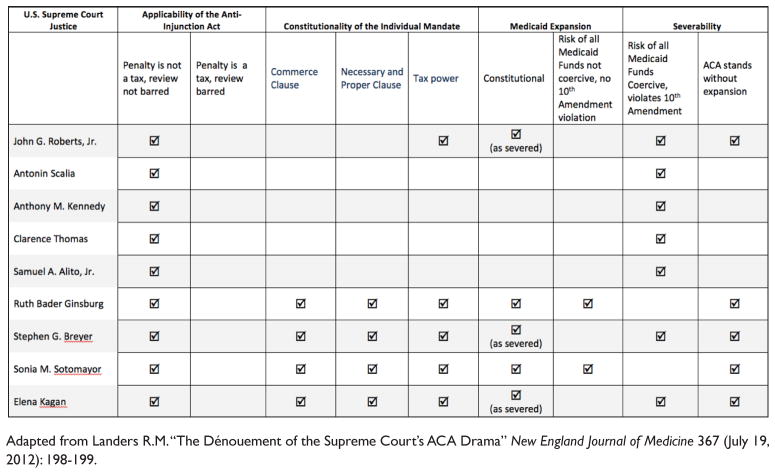

The U.S. Supreme Court was petitioned to hear the case against the PPACA in September 2011, and the writ of certiorari was granted on November 14, 2011,1 indicating the Court’s intention to resolve several constitutional questions about the law. In four extraordinary sessions on March 26–28, 2012, the Court heard arguments for and against several aspects of the law. It handed down its decision on June 28, 2012, and, to the surprise of most observers, upheld the most critical component of the law, the insurance mandate.2 It is not surprising, however, that debate over the policies enacted under the law has not cooled; rather, it has become, if anything, more intense, and is likely to be a major factor in the presidential and congressional elections this November. The breakdown of how each justice voted is depicted in the Figure.

Figure 1.

How the Justices Voted on the Several Disputed Sections of the PPACA

This symposium’s debates and point-counterpoint sessions dealt with fundamental issues, so the discussions are just as relevant today as they were when the conference was held. The topics addressed such issues as the responsibilities of individuals versus those of society to provide health care, the morality of market-based health care reforms, the effectiveness of consumer-driven health care reforms, and the role of the principle of justice in grounding health care reform. Much political jousting over the PPACA will precede the elections of 2012, and all of the issues discussed in this symposium will explicitly or implicitly play an important role in the resulting polemics.

Addressing the question of who is responsible for health care, Allan Brett points to a national commitment to rescue people with urgent medical needs, a commitment that requires physicians to advocate for universal access to health care.3 Ronald Hamowy also sees our society as essentially compassionate, but argues that compassion should not be expressed in the form of political coercion to support health care; rather, because free markets are far more efficacious than coercive laws in addressing social problems, he asserts that the generosity and charity of the American people will ensure that no one in need of health care will be denied.4

James Taylor argues that free-market provision of health care is more efficient than its provision by government and is more morally sound because it better respects the autonomy of persons by refraining from imposing values upon them.5 Taking an opposing position, Len Nichols grounds the morality of the PPACA in scriptural concepts of community and mutual obligation; he advocates implementing, with appropriate amendments, the PPACA as rapidly and fully as possible.6

In defending the efficacy of consumer-driven health care, Robert Moffit asserts that health care reform should be aligned with the primacy of personal choice and expand consumer control through defined-contribution financing, which will make the provision of health care far more efficient than it is today.7 John Geyman, to the contrary, asserts the opposite: consumer-driven reforms, he says, have been ineffective in containing costs, and, by restricting access to care, have led to underuse of necessary care, lower quality, and worse outcomes.8

Paul Menzel grounds his belief in mandating insurance for a basic minimum of care on the dual principles of social justice and just sharing of the costs of illness (with its corollary principle of fairness).9 Griffin Trotter disagrees, arguing that no single conception of justice can ground health care reform because to do so would require both nationally widespread support for a particular conception of justice and belief that this conception provides strong rationale for health care reform — neither of these conditions is met in this country today.10

The PPACA has largely survived constitutional challenges. In his critical majority-creating opinion on the insurance mandate, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote: “Members of this Court are vested with the authority to interpret the law; we possess neither the expertise nor the prerogative to make policy judgments. Those decisions are entrusted to our Nation’s elected leaders, who can be thrown out of office if the people disagree with them. It is not our job to protect the people from the consequences of their political choices.”11 He was, in essence, thrusting the debate back into the political arena, where, in his view, it properly belongs. Whether that view is correct or not, the future of the PPACA is now clearly a political question that will be settled in the Congressional debates and executive decisions that will follow the elections of 2012.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute, Medical University of South Carolina’s Clinical and Translational Science Award Number UL1RR029882. The contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Biography

Robert M. Sade, M.D., Professor of Cardiothoracic Surgery and Director of the Institute of Human Values in Health Care at the Medical University of South Carolina. He currently chairs the Ethics Committee of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and is an Associate Editor (Ethics) for the Annals of Thoracic Surgery. He is a recent chair of the Society of Thoracic Surgeon’s Standards and Ethics Committee and the American Medical Association’s Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs.

References

- 1.National Federation of Independent Business et al., Petitioners, v. Kathleen Sebelius, Secretary of Health and Human Services, et al., Supreme Court of the United States, 11 U.S. 393–400 (2011).

- 2.Landers RM. The Dénouement of the Supreme Court’s ACA Drama. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012 Jul 19;367(3):198–199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1206847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brett AS. Physicians Have a Responsibility to Meet the Health Care Needs of Society. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2012;40(3):526–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamowy R. Medical Responsibility. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2012;40(3):532–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor JS. Market-Based Reforms in Health Care Are Both Practical and Morally Sound. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2012;40(3):537–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nichols LM. Government Intervention in Health Care Markets Is Practical, Necessary, and Morally Sound. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2012;40(3):547–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moffit RE. Expanding Choice through Defined Contributions: Overcoming a Non-Participatory Health Care Economy. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2012;40(3):558–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geyman JP. Cost-Sharing under Consumer-Driven Health Care Will Not Reform U.S. Health Care. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2012;40(3):574–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menzel PT. Justice and Fairness: A Critical Element in U.S. Health System Reform. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2012;40(3):582–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trotter G. No Theory of Justice Can Ground Health Care Reform. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2012;40(3):598–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Federation of Independent Business et al. v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 6 (2012).