INTRODUCTION

The autoinflammatory syndromes comprise a clinically distinct set of disorders unified by recurrent febrile episodes accompanied by inflammatory cutaneous, mucosal, serosal, and osteoarticular manifestations.1–3 Although these rare disorders often have a striking onset and inflammatory features, they are without an infectious or autoimmune cause. Instead, many are unified by a genetically driven dysregulated innate immune response with resultant activation of the inflammasome and cytokine excess. Hence, these disorders respond to interleukin (IL)-1 or tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and generally not to immunosuppressives. Manifestations include periodic fevers, neutrophilic rashes or urticaria, serositis, hepatosplenomegaly, lymph-adenopathy, elevated acute phase reactants, neutrophilia, and a long-term risk of secondary amyloidosis.

The identification of the genetic origins underlying certain disorders has rapidly advanced understanding of the immunopathogenesis of autoinflammatory disorders. Affected individuals often have first- or second-degree relatives with similar features. A monogenic defect has been identified for familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), TNF receptor–associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), hyperimmunoglobulinemia D with periodic fever syndrome (HIDS), and cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS)—which include a spectrum of disorders: familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID). Additional disorders also fall under the autoinflammatory umbrella, because they manifest similar inflammatory features but may or may not have an identifiable genetic cause. Etiologic defects have been discovered for cyclic neutropenia; pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne (PAPA) syndrome; pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) syndrome; deficiency of the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) (DIRA); and deficiency of the IL-36R antagonist (DITRA). Those without a known cause include systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SoJIA); adult-onset Still disease (AOSD); periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenopathy (PFAPA) syndrome (or Marshall syndrome); and Schnitzler syndrome.1–5

Although these disorders are often rare, some are more frequently seen than others. A federally funded German registry was established in 2009 and in a 9-month period they identified 117 patients (65 male and 52 female; ages 1–21 years) with a diagnosis of FMF (n = 84), SoJIA (n = 22), clinically confirmed AIDS (n = 5), TRAPS (n = 3), CAPS (n = 1), HIDS (n = 1), and PFAPA (n = 1).6 This review focuses on the distinguishing clinical features, onset, fever/flare duration, etiology, and effective treatments—each of which is crucial to establishing an accurate diagnosis.

ETIOLOGY

Immune responses are either innate or adaptive. The adaptive immune response recognizes self from nonself and generates antigen-specific cellular and cytokine responses, and, with activation-driven autoantibody production, the adaptive responses can establish immunologic memory or immune tolerance. By contrast, the innate immune response acts with immediacy to danger or pathogen signals, termed pathogen-associated molecule patterns (PAMPs) and endogenous damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). PAMPs and DAMPs activate intracellular inflammasomes to set forth an inflammatory cascade of effector molecules.3,4 For example, the NLRP3 inflammasome is a cytosolic scaffold of proteins triggered by PAMPs (microbial pathogens, monosodium urate, and toxins) and DAMPs (ATP, membrane disruption, oxygen radicals, and hypoxia). A disrupted, dysregulated innate immune system yields a proinflammatory state, with the final common pathway being activation of the NLRP3 gene and the inflammasome, with resultant unopposed cytokine excess. Activation of the inflammasome yields increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-18, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17, type 1 interferons (IFN-α and IFN-β), and the complement system. The inflammasome is a complex of proteins that activates caspase-1, leading to cleavage of inactive pro-IL-1β to active IL-1β. The critical role of the inflammasome in these disorders has led some to refer to the autoinflammatory disorders as inflammasomopathies.7

TRAPS

TRAPS is also known as familial Hibernian fever, owing to a higher frequency of this syndrome in those of Irish, Scottish, or Austrian or Northern European dissent. Nevertheless, it has been described in other ethnic groups, including Mediterraneans. TRAPS differs from FMF and HIDS by having febrile attacks that last 1 to 3 weeks and occasionally up to 6 weeks. Characteristic features include fever, arthralgia, myalgia, migratory rash, abdominal pain, pleuritis, conjunctivitis, periorbital edema, oral ulcers, and scrotal swelling. Skin manifestations include migratory macular erythematous rash or patches, ecchymoses, edematous dermal plaques, serpiginous or annular lesions, and periorbital edema.5,8,9 Limited skin biopsies showed perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic and mononuclear infiltrates without evidence of granulomatous or vasculitic change.

The genetics underlying this disorder was clarified by studies of a large Irish multiplex family who demonstrated an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by recurrent fever, rash, and abdominal pain. Fevers last more than 5 days and less than 6 weeks. The vast majority (75%–88%) has childhood onset, usually as toddlers at approximately age 3 years and most occurring before age 10 years. Adult onset may occur. Manifestations of TRAPS depend on the mutations for the gene encoding p55 TNF receptor type I (CD120a). There are 46 known missense mutations involving TNF receptor type I, all of which are localized to distal chromosome 12p. The R92Q and P46L mutations are seen in 4% and 1% of the population, respectively, and tend to have low penetrance and less severe disease. The R92Q and T61I polymorphisms may be found with an adult onset and are often associated with rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or multiple sclerosis. There is effective treatment with etanercept, which has been shown to reduce the frequency and severity of flares.9 There are reports of efficacy with anakinra and worsening with infliximab.

HYPER IgD SYNDROME

HIDS is a rare disorder that begins early in life, usually before 2 years of age. Most reports have been seen in those of northern European, Dutch, or French ancestry.1,2,10,11 HIDS has inflammatory symptoms lasting 3 to 7 days with recurrent fever, chills, cervical lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, hepatosplenomegaly, diarrhea, arthralgia or arthritis, aphthous ulcers, skin rash (usually palmar/plantar), and headaches. Vaccinations may precipitate in inflammatory attacks in some patients. High levels of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and serum amyloid A are seen, and IgD levels greater than 100 IU/dL are sensitive but not specific for HIDS. In 1999, mevalonate kinase (MVK) gene mutations were found in patients with HIDS. Currently, tests for the MVK gene are the gold standard in diagnostic testing. HIDS is an autosomal recessive disorder, with defects in the gene encoding MVK, an enzyme central to cholesterol synthesis. Although colchicines and steroids are sometimes effective, anakinra has become the drug of choice because it has been more uniformly beneficial in observational reports.1,10

FAMILIAL MEDITERRANEAN FEVER

FMF is the most common of the ancestral or monogenic autoinflammatory disorders.1–6 FMF preferentially affects Sephardic Jews, Armenians, Turks, North Africans, Arabs, Moroccans, and others whose familial origins can be traced to the Mediterranean basin. Although the vast majority of cases have Mediterranean roots, ancestry should not exclude this diagnosis or the need for genetic testing if the clinical picture is suggestive, because many non-Mediterraneans have been diagnosed with FMF. The disorder often begins in childhood or adolescence, and up to 20% may have their first attack after the age of 20 years. Younger cases usually have more striking features, and severity lessens with age. FMF is characterized by febrile episodes accompanied by cutaneous, serosal, or synovial/tenosynovial inflammation. Fevers are usually 38°C or higher and last 1 to 3 days, ending as abruptly as they begin. Bouts are unpredictable in their frequency and are usually without known triggers but may be provoked by infection, stress, exercise, or surgery. Cutaneous features are distinctive, if not pathonomonic, and manifest as unilateral, more so than bilateral, erysipelas-like erythema that is often painful and located on the extensor surface of the arms, legs, or dorsum of feet. Also distinctive is the occurrence of recurrent inflammatory, sterile, monarticular inflammatory joint effusions or tenosynovial swelling. Less commonly, myalgia, migratory arthritis, and destructive/erosive arthritis may occur. Serositis manifests as either pleuritis or peritonitis with abdominal pain and, less frequently, as pericarditis or scrotal swelling. Rare manifestations include aseptic meningitis, orchitis, and vasculitis. Laboratory findings include leukocytosis and marked elevations of the ESR and CRP during the attacks. Amyloidosis may complicate FMF with serum amyloid A deposition in the kidney or other organs. Amyloidosis is more common with M694V homozygocity, male patients, and the alpha/alpha serum amyloid A1 gene. Amyloidosis is unrelated to the severity of FMF and can be diagnosed by biopsy of the rectum, kidney, abdominal fat, or bone marrow.

FMF results from a recessive mutation of the MEFV or Mediterranean Fever gene 16p13. This recessive mutation is located on the short arm of the chromosome 16. The zygosity and type of mutation determines the severity of the disorder and age of onset in many. In FMF, there are more than 80, mostly missense, mutations with the 5 most common genotypes (M694V, M6941, M680I, V726A, and E148Q) accounting for nearly 80% of cases. The dominant mutation depends on the population: V726A is common among Ashkenazi and Iraqi Jews, Druzes, and Armenians; M680I is frequent in Armenians and Turks; M694I and A744S in Arabs; and R761H in Lebanese patients. MEFV is found in neutrophils and myeloid cells and encodes an 86-kDa protein, called pyrin (or marenostrin). Defective pyrin function leads to uncontrolled inflammation with elevated levels of IFN-γ and circulating proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8.

Many patients with FMF respond favorably to colchicine. Colchicine is effective in both aborting and preventing attacks and, when used chronically, decreases the risk of amyloidosis. Most patients respond well with only a minority refractory to colchicine—either because of dose-limiting gastrointestinal toxicity or more-aggressive disease. Steroids may be effective but are seldom needed. Refractory cases respond well to IL-1 inhibition (with anakinra, canakinumab, or rilonacept).1,10

The diagnosis of FMF should be a largely clinical one, based on recurrent 1- to 4-day bouts of fever with synovial, serosal, or skin inflammation and high acute-phase proteins. Confirmation by MEFV testing may be necessary in atypical cases and those evidently not of Mediterranean ancestry.

CRYOPYRIN-ASSOCIATED PERIODIC SYNDROMES (CRYOPYRINOPATHIES)

The CAPS are a distinct subset of autosomal dominant disorders etiologically connected by mutations of the NACHT domain of NLRP3, previously known as cryopyrin.1–4,12 NLRP3 (which stands for NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain 3) includes the cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome 1 (CIAS1) gene and, as such, much of the literature suggests that these disorders are related to defects in CIAS1. CIAS1 encodes for cryopyrin, a protein similar to pyrin that is also expressed primarily in neutrophils and monocytes. CAPS include familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID) also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome (CINCA). The severity of disease is milder in FCAS and MWS but tends to be the most severe in NOMID, with often devastating neurologic complications. Common features of CAPS, regardless of the specific clinical entity, include fever, urticarial-like rash, conjunctivitis, bone and joint symptoms, and elevated inflammatory markers, such as CRP. There is little/no risk of amyloidosis with chronicity. CAPS patients have uniformly responded well to IL-1 inhibition (anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab).11

FCAS begins in infancy and is unique by being provoked by cold exposure, with brief episodes (lasting <24 h) of urticarial-like rash, fever, conjunctivitis, and joint/limb pain. Although some patients have significant disability related to these attacks, long-term prognosis is favorable for most.

MWS has an older onset (adolescents and young adults), with fevers lasting up to 7 days. Frequent attacks and chronicity may be accompanied by sensorineural hearing loss or deafness and a long-term risk of amyloidosis.12

NOMID is the most severe form of CAPS and differs from FCAS and MWS by being chronic, rather than episodic, in its manifestations. It is characterized by a neonatal or infantile onset of chronic urticarial rash, low-grade fever, otolaryngologic findings, sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, and, later, chronic aseptic meningitis, which may result in cerebral atrophy, seizures, hearing and vision loss, and mental retardation. NOMID patients may develop a distinctive overgrowth of the epiphyses in the long bones, with resultant deformity, leg length discrepancy, joint contractures, or premature degenerative arthritis. Late closure of the fontanel leads to frontal bossing. Amyloidosis is a known risk and mortality may be as high as 20%. Before administration of IL-1 antagonistic therapy, the prognosis for patients with NOMID was poor.

STILL DISEASE

Still disease is another name for systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SoJIA) and the adult continuum of that disease, adult-onset still disease (AOSD). AOSD and SoJIA are considered under the autoinflammatory syndromes, because they are often confused with these disorders, share many of the same clinical features, and seem uniquely responsive to IL-1 (or IL-6) inhibition. Still disease is a systemic inflammatory disorder of unknown cause or genetics that typically affects children under 16 years of age (SoJIA) or young adults from ages 18 to 35 years (AOSD). The classic triad includes quotidian (daily) spiking fevers (≥39°C), juvenile idiopathic arthritis or rheumatoid rash, and polyarthritis.13,14 The cutaneous features associated with AOSD include pruritis, urticaria (<40%), and salmon-pink evanescent (changes day to day) rash usually on the trunk, neck, and extremities and almost never on the face, palms, or soles. Other characteristic manifestations include a prodromal sore throat (in adults, not children), arthralgias, myalgias, rapid weight loss, serositis (pleuritis or pericarditis), generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly (often with elevated hepatic enzymes), and splenomegaly. Laboratory tests support the inflammatory nature of the disorder with neutrophilic leukocytosis, very high ESR and CRP, anemia of chronic disease, hypoalbuminemia, and absence of serum rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies. The importance of hyper-ferritinemia has been overstated by most investigators because only 50% have elevated ferritin levels (compared with >90% ESR or CRP elevations) and extreme elevations, greater than 2000 mg/dL, are seen in 10% to 20% of patients with active systemic disease. These features are not intermittent (as they are in TRAPS or FMF) but instead are daily and quotidian, with a regular periodicity to the fever, rash, myalgias, and arthralgias.

The clinical course is marked by sporadic exacerbations of systemic inflammation (fever, rash, serositis, and inflammatory labs) and/or chronic inflammatory arthritis. There are no diagnostic clinical manifestations, serologic tests, or histopatho-logic findings; thus, the diagnosis can be based on criteria by either Cush13 or Yamaguchi and colleagues14 after exclusion of common infectious or neoplastic conditions.13,14 Persistence of symptoms (fever rash, polyarthritis, hepatosplenomegaly, and so forth) beyond 6 weeks is necessary for considering a diagnosis of AOSD.

There is no known cause of AOSD or SoJIA, although several groups have noted polymorphisms in either the IL-18 or IL-1 genes. A minority of patients may respond to antiinflammatory doses of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs but most require high-dose oral corticosteroids (ie, prednisone, 40–60 mg/d) with or without methotrexate or azathioprine to achieve partial control of systemic inflammatory activity. Refractory patients or those with recurrent systemic disease have shown a remarkable response to anakinra and other IL-1 inhibitors (canakinumab and rilonacept). TNF inhibitor therapy seems effective in patients with chronic inflammatory polyarthritis but is less successful in managing systemic manifestations.15,16

OTHER AUTOINFLAMMATORY DISORDERS

The PFAPA syndrome, also known as Marshall syndrome, affects children more than adults (from 5–35 y) and is predictable in the periodicity of febrile attacks that last an average of 4 to 5 days and recur approximately every 4 weeks.17 In the interim, patients are healthy and asymptomatic. During febrile attacks, patients manifest aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, tender cervical lymphadenitis, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. There is no hearing loss or amyloidosis with the PFAPA syndrome. Treatment may include a single dose of corticosteroid (chronic cimetadine use is effective in less than 25%) or surgical removal of tonsils. Some patients have responded to anakinra. There is no known cause.

PAPA syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder that affects children and adolescents with recurrent pyogenic, sterile arthritis with pustular skin lesions (eg, pyoderma gangrenosum and acne fulminans, cystic acne, and pathergy) but no febrile episodes.6,18,19 In some patients, the arthritis may be severe, destructive, or deforming. PAPA is the result of a missense mutation in the adapter protein proline-serine-threonine phosphatase-interacting protein (PSTPIP1) gene. The skin lesions of PAPA have responded to TNF inhibitors as well as IL-1 inhibitors.

The triad of PASH is included as an autoinflammatory syndrome that affects adults and adolescents and is similar to PAPA but differs by having hidradenitis suppurativa without pyogenic arthritis or fevers.18 Early results suggest these patients may respond to IL-1 inhibitors. Gene mutations for PAPA and other autoinflammatory disorders (eg, PSTPIP1, MEFV, NLRP3, and TNFRSF1A) have been absent. The cause is currently unknown.

Schnitzler syndrome is a rare disorder of unknown cause and is thought to be an acquired auto-inflammatory disorder because it typically affects older individuals (40–60 years). Of the more than 100 cases reported, few have been seen in the United States. Typical manifestations include nonpruritic urticaria and a monoclonal gammopathy (usually IgM kappa), with at least 2 of the following: periodic fever, arthralgia or arthritis, bone pain, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, elevated ESR, leukocytosis, and anemia. Other features include weight loss and pancreatitis. Dramatic responses have been seen with anakinra treatment. There is a rare long-term risk of developing a lymphoproliferative disorder (mainly Waldenström macroglobulinemia).20

DIRA is a rare, inherited disease that results from a deficiency of IL-1Ra and was initially described in patients from Newfoundland, Holland, Lebanon, and Brazil.21 Lack of the IL-1Ra leads to unopposed IL-1 activity and chronic pustular skin disease. It begins in infancy and manifests as neutrophilic/pustular skin disease, pathergy, periostitis, multifocal osteomyelitis, oral mucosal lesions, nail dystrophy, and joint/bone pain. Laboratory results show elevated acute phase proteins. Radiographic changes include osteitis of the ribs and long bones and heterotopic ossification with periarticular soft tissue swelling. Treatment with anakinra leads to dramatic improvement and may abort significant morbidity and mortality if recognized early.

DITRA is a newly recognized entity wherein a mutation in the IL-35Ra gene results in either familial or sporadic cases of generalized pustular psoriasis that responds to IL-1 inhibition.21 It is possible that this may be related to acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau that manifests as chronic, pustular eruptions involving the fingertips and nails.

Cyclic neutropenia is a disorder with recurrent fevers that last 5 to 14 days, recurs every 21 to 35 days, and coincides with episodic neutropenia (neutrophils ≤500/mm3). Common features include fatigue, pharyngitis, oral ulcers, stomatitis, cellulitis, and lymphadenopathy.22 Such patients are at risk for infection and sepsis and this auto-somal dominant disorder results from a mutation in the neutrophil elastase gene (ELA-2 or ELANE). Cyclic neutropenia differs from congenital neutropenia, which has more profound neutropenia and greater risk of infection. Effective treatments include granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF), steroids and, in some cases, cyclosporine.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH TO PERIODIC FEBRILE DISORDERS

Advances in understanding of the pathogenesis and genetics of these disorders have led to testing, which may ultimately diagnose one of these rare disorders. To pursue genetic testing, however, clinicians need to have sufficient clinical grounds for ordering such tests. Hence, a complete clinical evaluation is necessary to characterize features that are most diagnostic. Although autoinflammatory disorders may have markedly elevated acute-phase reactants, anemia of chronic disease, neutrophilic leukocytosis, non-specific perivascular inflammation on skin biopsy, negative serologic tests for autoantibodies, or a clinical response to steroids, colchicines, or IL-1 inhibition, these findings are nonspecific. If a periodic fever or autoinflammatory condition is suspected, it is important to exclude possible infectious, neoplastic, or autoimmune disease based on the manifestations and pattern of organ involvement. Common adult causes of fever of unknown origin include polymyalgia rheumatic, giant cell arteritis and other systemic necrotizing vasculitides, lupus, tuberculosis and occult infections, lymphoma, leukemia, and inflammatory bowel disease. Once these are excluded, an autoinflamma-tory disorder can be considered.

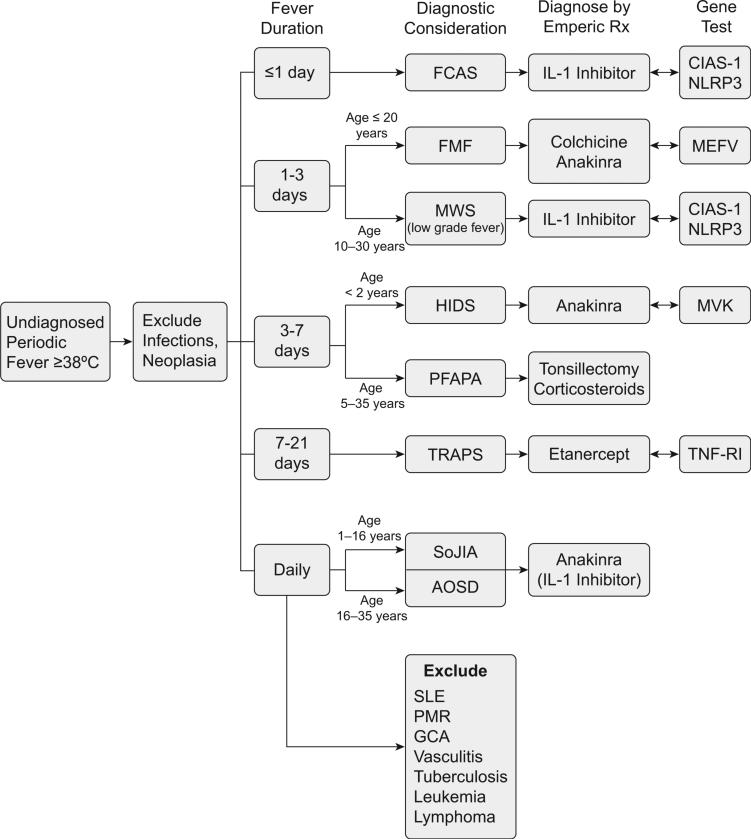

The clinical features that are most predictive in making a diagnosis are (1) age of onset; (2) presence, magnitude, and duration of fever; (3) duration of attacks; (4) rash or urticaria; (5) distinguishing features (Tables 1 and 2) (eg, serositis, arthritis, organomegaly, ocular, or neurologic involvement); (5) ethnicity; and (6) family history of similar illness. Fig. 1 details an algorithmic approach to patients with undiagnosed periodic fevers, initially focusing on the duration of febrile attacks and the age of the individual at onset. Once a differential diagnosis is considered, confirmation may ensue by either an empiric trial of known effective therapy or the identification of a genetic mutation with commercially available tests. The downside of genetic testing is that not all patients with an apparent autoinflamma-tory disorder prove to have an identifiable known genetic anomaly. Moreover, widespread batteries of tests or screening for multiple gene mutations have not been shown to be either cost effective or diagnostically prudent.

Table 1.

Autoinflammatory syndromes: acronyms, meanings, and overview

| Acronym | Meaning | Clinical Overview |

|---|---|---|

| AOSD | Adult-onset Still disease | Quotidian fevers >39°C, polyarthritis, rash, serositis, lymphadenopathy, organomegaly |

| CAPS | Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes | Includes FCAS, MWS, NOMID/CINCA |

| CINCA | Chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome (same as NOMID) | Severe form of CAPS with infantile onset, chronic urticaria, neurologic involvement |

| DIRA | Deficiency of the IL-1Ra | Pustular lesions, periostitis, osteomyelitis, mucosal lesions |

| DITRA | Deficiency of the IL-36R antagonist | Chronic pustular psoriasis |

| FCAS | Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome | Infants with cold induced fever, urticaria, conjunctivitis, joint/bone pain |

| FMF | Familial mediterranean fever | Periodic fevers, red painful rash, serositis |

| HIDS | Hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome | Recurrent fever, cervical lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, hepatosplenomegaly, arthralgia or arthritis, aphthous ulcers |

| MWS | Muckle-Wells syndrome | Adolescents/adults with fever, urticaria, sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus |

| NOMID | Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease | Severe form of CAPS with infantile onset, chronic urticaria, neurologic involvement |

| PAPA | Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne | Recurrent pustular skin lesiosn (pyoderma gangrenosum) with recurrent pyogenic, sterile arthritis |

| PASH | Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, suppurative hidradenitis | Same as PAPA without the pyogenic arthritis |

| PFAPA | Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenopathy | Children with monthly fevers (last 4 d), aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, cervical lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain |

| SoJIA | Systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Children (3–16 y) with quotidian fevers >39°C, polyarthritis, rash, serositis, lymphadenopathy, organomegaly |

| TRAPS | TNF receptor–associated periodic syndrome | Toddlers with recurrent fever (>1 wk), arthralgia, myalgia, migratory rash, abdominal pain, pleuritis, conjunctivitis, periorbital edema |

Table 2.

Distinctive features among the autoinflammatory disorders

| Disease | Genetics, Mutation |

Onset Age | Fever/Flare Duration |

Mucocutaneous | Musculoskeletal | Other Significant Findings |

Effective Therapya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRAPSb (Hibernian fever) | Autosomal dominant, TNFR1 | Infants, rarely adults | Usually 1–3 wk | Erthematous rash or dermal plaques on extremities | Myalgia Arthralgia (erosive synovitis is rare) | Serositis, abdominal pain, conjunctivitis periorbital edema | Etanercept Anakinra |

| FMFb | Autosomal recessive, MEFV gene | <20 y in 80% of patients | ≥39°C 1–3 d |

Erysipelas-like | Recurrent monarthritis, tenosynovitis, arthralgias, myalgia | Abdominal pain, serositis, scrotal swelling | Colchicine Anakinra Rilonacept |

| HIDS | Autosomal recessive, MVK gene | <2 y | 3–7 d | Palmar/plantar rash, aphthous ulcers | Arthralgia Arthritis |

Cervical adenitis, abdominal pain, | Anakinra |

| FCAS | Autosomal dominant, NLRP3 | <1 y | <24 h | Urticaria | Arthralgias | Cold-induced conjunctivitis | Avoid cold Anakinra Rilonacept Canakinumab |

| Muckle-Wellsb | Autosomal dominant, NLRP3 | Variable; infants, teens, young adults | Low-grade fever 1–3 d |

Erythematous rash, urticaria (sometimes cold-induced) | Myalgias, arthralgias, arthritis | Conjunctivitis, uveitis, sensorineural hearing loss, fatigue | Anakinra Rilonacept Canakinumab |

| NOMIDb | Sporadic, NLRP3 | <1 y | Mild fevers, constant | Chronic urticarial-like skin rash | Arthralgia, arthritis, bony overgrowth of epiphysis, bony hypertrophy/deformity, frontal bossing | Chronic uveitis Conjunctivitis, chronic aseptic meningitis, sensorineural hearing loss, headaches, papilledema, optic atrophy, visual loss, mental retardation | Anakinra Rilonacept Canakinumab |

| AOSD and SoJIA | Acquired; no known genetic link | 3–35 y | ≥39°C, daily quotidian fevers | Evanescent pink rash, 30%–40% pruritic or urticarial | Polyarthritis Polyarthralgia Myalgia Carpal anklyosis |

Prodromal sore throat, serositis, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly | Steroids Methotrexate Anakinra (IL-1 inhibitors) |

| PFAPA | Unknown | 5–35 y | q 4 wk; Lasting 4–5 d | Aphthous ulcerations | None | Pharyngitis cervical adenitis, abdominal pain | Tonsillectomy Single steroid dose Cimetadine Anakinra |

| PAPA | Autosomal dominant, PSTPIP1 gene | Children adolescents adults | None | Acne Pyoderma gangrenosum Pathergy |

Inflammatory arthritis mostly large joints (some erosive or deforming) | TNF inhibitors IL-1 inhibitors |

|

| Cyclic neutropenia | Autosomal dominant, neutrophil elastase gene (ELA-2 or ELANE) | Child to adult | 10–14 d of low-grade fevers; recurs q 4–6 wk | Oral ulcers gingivitis periodontitis recurrent cellulitis or furunculosis | None | Malaise, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, LN, ST | G-CSF, steroids |

Adapted from Hoffman H, Patel D. Genomic-based therapy: targeting interleukin-1 for autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:345–9.

Associated risk for amyloidosis.

Fig. 1.

The approach to undiagnosed periodic fever.

SUMMARY

The autoinflammatory disorders can pose a significant challenge to pediatricians, internists, primary care physicians, dermatologists, rheumatologists, and infectious disease specialists. Affected individuals often have either dramatic clinical presentations of fever of unknown origin or puzzling episodic febrile/cutaneous disease without evidence of infection of malignancy. The diagnosis of an autoinflammatory disorder can be made based on clinical features and supported by either genetic testing or response to IL-1 inhibition or other specific therapy.

KEY POINTS.

Autoinflammatory disorders are enigmatic and diagnostic challenges for clinicians.

Advances in understanding of genetic perturbations and role of the inflammasome have improved diagnostic and treatment approach to these disorders.

Many of the autoinflammatory disorders are suggested on the basis of individual age, duration of (febrile) attacks, and cutaneous manifestations.

Although many of the monogenic autoinflammatory disorders begin in neonates and children, adults may also be affected with new-onset or continued inflammatory disease.

Acknowledgments

Funded by: NIH U19 082715.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Clinical investigator for Genentech, Pfizer, UCB, Celgene, Novartis, Amgen, NIH, and CORRONA; advisor and consultant to Janssen, Abbott, UCB, Pfizer, BMS, Amgen, Genentech, Savient, and Celgene. Dr Cush holds no stock or investments in these companies and does not partake in industry “speaker’s bureaus” or give industry-guided “promotional lectures.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Zeft AS, Spalding SJ. Autoinflammatory syndromes: fever is not always a sign of infection. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:569. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.79a.11184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fietta P. Autoinflammatory diseases: the hereditary periodic fever syndromes. Acta Biomed. 2004;75:92–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozkurede VU, Franchi L. Immunology in clinic review series; focus on autoinflammatory diseases: role of inflammasomes in autoinflammatory syndromes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167(3):382–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menu P, Vince JE. The NLRP3 inflammasome in health and disease: the good, the bad and the ugly. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;166:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long SS. Distinguishing among prolonged, recurrent, and periodic fever syndromes: approach of a pediatric infectious diseases subspecialist. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52(3):811–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lainka E, Bielak M, Lohse P, et al. Familial mediterranean fever in Germany: epidemiological, clinical, and genetic characteristics of a pediatric population. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171(12):1775–85. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1803-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith EJ, Allantaz F, Bennett L, et al. Clinical, molecular, and genetic characteristics of PAPA syndrome: a review. Curr Genomics. 2010;11(7):519–27. doi: 10.2174/138920210793175921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toro JR, Aksentijevich I, Hull K, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome: a novel syndrome with cutaneous manifestations. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(12):1487–94. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.12.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulua AC, Mogul DB, Aksentijevich I, et al. Efficacy of etanercept in the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome: a prospective, open-label, dose-escalation study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(3):908–13. doi: 10.1002/art.33416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Hilst JC, Bodar EJ, Barron KS, et al. International HIDS Study Group. Long-term follow-up, clinical features, and quality of life in a series of 103 patients with hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87(6):301–10. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318190cfb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman H, Patel D. Genomic-based therapy: targeting interleukin-1 for autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:345–9. doi: 10.1002/art.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Koitschev A, Ummenhofer K, et al. Hearing loss in Muckle-Wells syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(3):824–31. doi: 10.1002/art.37810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cush JJ. Adult onset Still's disease. Bull Rheum Dis. 2000;49(6):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(3):424–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petryna O, Cush JJ, Efthimiou P. IL-1 Trap rilonacept in refractory adult onset Still's disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(12):2056–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Efthimiou P, Petryna O, Mehta B, et al. Successful use of canakinumab in adult-onset Still's disease refractory to short acting IL-1 inhibtors. EULAR. 2012:THU0401. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kyvsgaard N, Mikkelsen T, Korsholm J, et al. Periodic fever associated with aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and cervical adenitis. Dan Med J. 2012;59(7):A4452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindor NM, Arsenault TM, Solomon H, et al. A new autosomal dominant disorder of pyogenic sterile arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne: PAPA syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(7):611–5. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63565-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)—a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(3):409–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Besada E, Nossent H. Dramatic response to IL1-RA treatment in longstanding multidrug resistant Schnitzler's syndrome: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(5):567–71. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cowen EW, Goldbach-Manksky R. DIRA, DITRA, and new insights into pathways of skin inflammation: What's in a name? Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(3):381–4. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dale DC, Welte K. Cyclic and chronic neutropenia. Cancer Treat Res. 2011;157:97–108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7073-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]