Abstract

An electrophilic bromine catalyzed skeletal rearrangement of an Δ4-oxocene to an epoxy furan has been described. This skeletal rearrangement suggests a plausible mechanism for the biosynthesis of the C15-acetogenin laurepoxide.

Keywords: laurepoxide, biosynthesis, rearrangement, Δ4-oxocene epoxide

Graphical abstract

Introduction

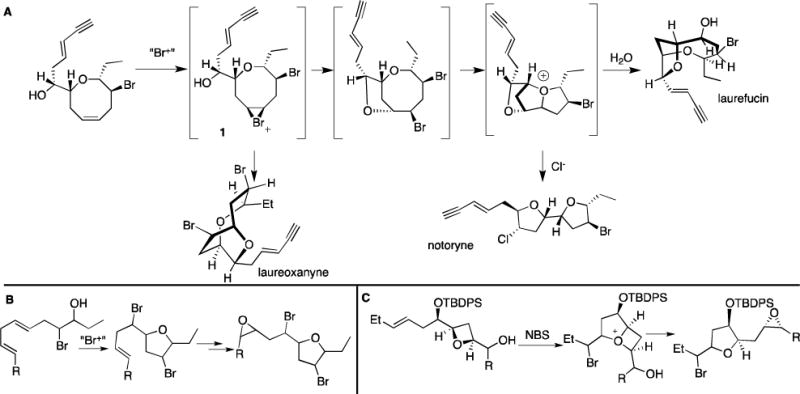

Since the initial isolation of Laurencin in 1965, a wide variety of small and medium-ring ether, halogenated natural products have been isolated from Laurencia red algae.1 The considerable structural diversity of these natural products has invited curiosity as to their biosynthetic origins, with representative members shown in Figure 1. In an elegent series of studies, Fukuzawa and Murai showed that haloether deacetyllaurencin, upon exposure to lactoperoxidase, halide and hydrogen peroxide, was transformed into a diverse array of other natural products including laureoxanyne, laurefucin, and notoryne (Scheme 1a).2–4 These findings are strongly suggestive of the existence of key transient bromonium species 1, which can undergo an intramolecular bromoetherification and subsequent oxonium ylide-induced reactions to yield the observe products (Scheme 1a). Structural variants bromofucin5 and chlorofucin6 are also believed to be accessed via analogous bromonium intermediates. These biosynthetic proposals for electrophile-initiated transannulation have inspired the synthetic community. Kim exploited a selenoetherification approach in his syntheses of laurefucin7 and elatanyne,8 and a bromoetherification approach in his syntheses of ent-bromofucin,8 laureatin and iso-laureatin.9 Suzuki utilized an epoxidation followed by intramolecular ring opening sequence towards (Z)-laureatin.10

Figure 1.

Representative C15-acetogenins

Scheme 1.

a) Fukuzawa and Murai’s proposed biosynthesis of various bromoethers stemming from bromonium 1. b) Proposed biosynthesis of brominated THF’s from linear polyenes. c) Howell’s skeletal rearrangement.

Less well understood is the biosynthesis of epoxy tetrahydrofuran natural products2 such as laurepoxide11 (Figure 1). Murai has shown that lactoperoxidase is capable of catalyzing the formation of 5-membered bromoethers from linear polyenes (Scheme 1b).3 Thus, it is plausible that epoxy tetrahydrofuran natural products arise from this type of reactivity, and the epoxide could be installed downstream via additional bromo-hydration reactions; but the latter has not been experimentally verified. Interestingly, Howell recently reported a skeletal rearrangement of an oxetane to yield an epoxy-furan structural motif similar to that found in the natural product laureoxolane (Scheme 1c).12

Intrigued by bromonium ion 1 and the potential chemistry of related ion 2 (Figure 2), we set out to study the chemistry of such intermediates in the context of biomimetic synthesis of halogenated Laurencia natural products. A possible fate of bromonium ion 2 would be bromoetherification to give the [5.2.1]-bicyclic core (3) found in bromofucin (Figure 2). An alternate fate of bromonium ion 2 would be intramolecular substitution by the oxocene to give oxocarbenium8, 10, 13 ion 4. Here, we describe an electrophilic bromine promoted skeletal rearrangement of an 8-membered Δ4-oxocene via putative oxocarbenium ion 4. The rearrangement suggests that it is possible that laurepoxide could arise from a bromonium ion similar to 2 via an intramolcular rearrangement process.

Figure 2.

Oxocene-derived bromonium ions had been shown to rearrange to bromoether products as found in bromofucin. Here, we provide evidence for oxocarbenium ion intermediates that rearrange to give the laurepoxide framework via oxocarbenium ion 4

To obtain Δ4-oxocene 9, the precursor to bromonium ion 2 we adapted Crimmins’ synthesis of Δ4-oxocenes used in his synthesis of laurencin (Scheme 2).14 Crimmins’ procedure utilizes an Evans’ chiral auxiliary approach to achieve stereoselective allylation which sets the key positions at C7 and C12, and thus allowed us to easily select for the S-stereochemistry found at C7 in bromofucin. This nine-step procedure additionally has the benefit of scalability with Δ4-oxocene 5 accessible on a multigram scale. With 5 in hand, the next task was to install a homoallylic alcohol at C6 in a stereoselective fashion (Scheme 2). Compound 5 was hydrolyzed under mild conditions15 and the crude acid 6 was directly carried onto Weinreb amide 7.16 Treatment of 7 with allylmagnesium bromide yielded ketone 8 in 77% yield. L-Selectride has previously been shown to provide excellent Felkin-Ahn stereoselectivity on ketone reductions in previous C15-acetogenin syntheses,7, 17 and proved equally effective in our hands, yielding 9 in 66% yield as a single diastereomer. The reaction of 9 with NBS was explored next. We anticipated that treatment of 9 with NBS may result in bromonium ion formation followed by subsequent trapping with the pendant hydroxyl group to form 3, which contains the [5.2.1]-oxabicyclic core of bromofucin. However, treatment of 9 with NBS in methylene chloride instead resulted in the isolation of tetrahydrofuran 10 as a single diasteromer in 45% yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Δ4-oxocene and subsequent skeletal rearrangement.

The formation of 10 suggested that NBS combines with 9 to form a bromonium ion 2 which is not attacked by the hydroxyl group. Species 2 is instead trapped by transannular attack of the oxygen in the Δ4-oxocene to yield oxocarbenium ion 4, which we subsequently undergoes intramolecular substitution by the hydroxyl group to yield the epoxy tetrahydrofuran 10 (Scheme 3a) as a single diasteromer. Compound 10 shares a skeletal framework with the natural product laureepoxide.11

Scheme 3.

a) Mechanistic rationale for the formation of 10. b) Kim’s synthesis of the core of ent-bromofucin. c) Suzuki and coworkers studied the reactivity of electrophilic bromine with 13, a compound that is structurally and stereochemically similar to 9. In the rearrangement to furan 2, bromonium ion 14 and oxocarbenium ion 15 were proposed.

Compound 10 was isolated as a single diastereomer, with new stereocenters created at C7, C9 and C10. The relative stereochemistry at C10 was assigned by a NOESY experiment, which shows NOE between C12–C13, but not between C10–C12 nor C10–C13 (supporting information). A cis-conformation of the epoxide is suggested by the coupling constant (4.5 Hz), and the configuration C7 is further supported by the mechanism of epoxidation that involves inversion at C7 on intermediate 4. The configuration at C9 could not be unambigously assigned. A mechanism that involves concerted transannular opening of bromonium ion 2 to give oxocarbenium 4 would produce the S-configuration (as displayed in Scheme 3). However, we cannot rule out a mechanism involving a free carbocation, which could result in R-configuration at C9, providing relative stereochemistry that is consistent with the reported structure of laurepoxide.9

Recently, Kim reported the bromoetherification of 11 to yield the bicyclic core (12) of ent-bromofucin.8 Compound 11 is quite similar to 9 with the exception of the C12 bromine already being installed and on the opposite face of the benzyloxy group of 9. This difference highlights the significant effect of backbone stereocenters in determining the fate of the bromonium ion, which in the case of 11 gives etherification in preference to oxocarbenium ion formation. (Scheme 3b).

The proposed facial selectivity for the formation of bromonium ion 2 and its rearrangement to oxocarbenium ion 4 is precedented by the work of Suzuki and co-workers10 (Scheme 3c) in their studies on the total synthesis of (+)-(Z)-laureatin. Δ4-oxocene 13, which is structurally and stereochemically analogous to our compound 9, was found to rearrange to keto-furan 16. The authors proposed that bromonium ion formation occurs on the β-face of the alkene and proposed a conformational model (14) for the intermediate bromonium ion. Transannular attack was proposed to give oxocarbenium ion 15– a structure consistent with the proposed intemediate 4.

These results suggest that Δ4-oxocene 17 may serve as the biosynthetic precursor laureepoxide via intermediate bromonium ion 18 (Scheme 4). Opening of 18 to carbocation 19 would provide a pathway to the reported structure of laureepoxide via oxocarbenium 20. By contrast, stereospecific opening of 18 would lead to the C-10 epimer of laureepoxide via intermediate oxocarbenium ion 21. Additional study would be necessary to confirm the stereochemical assignments in the literature,9 but is very plausible that the open carbocation pathway involving 19 and 20 would be favored due to the severe steric compression in 21.

Scheme 4.

Plausible biosynthesis of laureepoxide

In summary, we have discovered an electrophilic bromine promoted skeletal rearrangement of a Δ4-oxocene to yield the structural scaffold of C15-acetogenin laurepoxide. These observations highlight the need for additional study to further understand the biosynthesis of this natural product.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

For financial support we thank NSF CHE 1300329 and NIH NIH R01 GM068650. MTT is grateful to the NIH Chemistry-Biology Interface program, T32GM008550, for fellowship support. Data were obtained with instrumentation supported by NIH P30GM110758, NIH S10OD016267, NIH S10RR026962, and NSF CRIF:MU grants: CHE 0840401, CHE-1229234.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.a) Faulkner DJ. Nat Prod Rep. 1990;7:269–309. doi: 10.1039/np9900700269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Faulkner DJ. Nat Prod Rep. 1998;15:113–158. doi: 10.1039/a815113y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukuzawa A, Aye M, Takaya Y, Fukui H, Masamune T, Murai A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:3665–3668. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuzawa A, Aye M, Nakamura M, Tamura M, Murai A. Chem Lett. 1990;19:1287–1290. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukuzawa A, Aye M, Nakamura M, Tamura M, Murai A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:4895–4898. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coll JC, Wright AD. Aus J Chem. 1989;42:1685–1693. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard BM, Schulte GR, Fenical W, Solheim B, Clardy J. Tetrahedron. 1980;36:1747–1751. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim B, Lee M, Kim MJ, Lee H, Kim S, Kim D, Koh M, Park SB, Shin KJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16807–16811. doi: 10.1021/ja806304s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyson BS, Burton JW, Sohn T-i, Kim B, Hoon B, Kim D. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11781–11790. doi: 10.1021/ja304554e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim H, Lee H, Lee D, Kim S, Kim D. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2269–2274. doi: 10.1021/ja068346i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugimoto M, Suzuki T, Hagiwara H, Hoshi T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:1109–1112. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuzawa A, Kurosawa E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:1471–1474. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keshipeddy S, Martinez I, Castillo BF, II, Morton MD, Howell AR. J Org Chem. 2012;77:7883–7890. doi: 10.1021/jo301048z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oxocarbenium intermediates have been implicated in other syntheses of C15-acetogenins. For representative examples see 7, 8, 10 and the following:; a) Snyder SA, Treitler DS, Brucks AP, Sattler W. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15898–15901. doi: 10.1021/ja2069449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Snyder SA, Brucks AP, Treitler DS, Moga I. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:17714–17721. doi: 10.1021/ja3076988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bonney KJ, Braddock DC, White AJP, Yaqoob M. J Org Chem. 2011;76:97–104. doi: 10.1021/jo101617h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Braddock DC, Sbircea DT. Chem Commun. 2014;50:12691–12693. doi: 10.1039/c4cc06402j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For oxocarbenium intermediates arising from other Δ4-oxocenes, see:; e) Blumenkopf TA, Bratz M, Castaneda A, Look GC, Overman LE, Rodriguez D, Thompson AS. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4386–4399. [Google Scholar]; f) Paquette LA, Scott MK. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:6751–6759. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Crimmins MT, Emmitte KA. Org Lett. 1999;1:2029–2032. doi: 10.1021/ol991201e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Crimmins MT, Emmitte KA. Synthesis. 2000;6:899–903. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith TE, Richardson DP, Truran GA, Belecki K, Onishi M. J Chem Ed. 2008;85:695–697. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunishima M, Kawachi C, Morita J, Terao K, Iwasaki F, Tani S. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:13159–13170. [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Clark JS, Holmes AB. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:4333–4336. [Google Scholar]; b) Tsushima K, Murai A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:4345–4348. [Google Scholar]; c) Iida H, Yamazaki N, Kibayashi C. J Org Chem. 1986;51:3769–3771. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.