Abstract

Malaria is responsible for more deaths around the world than any other parasitic disease. Due to the emergence of strains that are resistant to the current chemotherapeutic antimalarial arsenal, the search for new antimalarial drugs remains urgent though hampered by a lack of knowledge regarding the molecular mechanisms of artemisinin resistance. Semisynthetic compounds derived from diterpenes from the medicinal plant Wedelia paludosa were tested in silico against the Plasmodium falciparum Ca2+-ATPase, PfATP6. This protein was constructed by comparative modelling using the three-dimensional structure of a homologous protein, 1IWO, as a scaffold. Compound 21 showed the best docking scores, indicating a better interaction with PfATP6 than that of thapsigargin, the natural inhibitor. Inhibition of PfATP6 by diterpene compounds could promote a change in calcium homeostasis, leading to parasite death. These data suggest PfATP6 as a potential target for the antimalarial ent-kaurane diterpenes.

Keywords: malaria, ent-kaurane diterpenes, PfATP6, docking, computer aided-drug design

Malaria is the most widespread infectious parasitic disease around the world (WHO 2013). The burden of emerging parasites resistant to artemisinin combination therapies threatens global efforts to control malaria, making the need for new antimalarial drugs urgent (Miller et al. 2013). However, the molecular mechanisms of artemisinin resistance are unknown (Nunes-Alves 2014). Among the numerous genes involved in artemisinin resistance, PfATP6, a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) homologue expressed in Plasmodium falciparum, has been suggested as a possible target of artemisinin (Valderramos et al. 2010, Cui et al. 2012).

Overcoming the major difficulties in the development of new antimalarial candidates relies on efficient candidate synthesis and a better understanding of the mechanism of action of defined targets (Médebielle 2014). In this context, our research group recently demonstrated the in vitro antiplasmodial activity of oxidised/epoxidised ent-kaurane diterpene derivatives obtained from the naturally occurring ent-kaurenes of Wedelia paludosa DC (Batista et al. 2013). Due to the selective antimalarial activity exhibited by these compounds and knowing that diterpenes induce calcium overload in myocytes (Sun et al. 2014) we investigated the interaction between the ent-kaurane diterpenes and PfATP6 (Gardner et al. 2002). SERCA are crucial for calcium signalling in malarial parasites (Furuyama et al. 2014, Krishna et al. 2014). Calcium signalling is associated with the regulation of many processes during the parasite life cycle, including modulation of kinase activity and synchronisation of the intraerythrocytic cycle (Bagnaresi et al. 2012). Molecular mechanisms that maintain parasite calcium homeostasis are controlled by proteins such as PfATP6 (Krishna et al. 2010). Any alteration to calcium homeostasis, triggered by the inhibition of PfATP6, could promote an increase in cytoplasmic calcium, leading to the activation of the metacaspase PfMCA-1 (Meslin et al. 2011). This mode of action could provide a new strategy to design new pro-apoptotic antimalarial drugs.

Thus, the aim of this study was to construct the PfATP6 enzyme model and perform a rigid and flexible molecular docking analysis of synthetic and semisynthetic diterpenes derived from W. paludosa DC.

Initially, the primary sequence of the PfATP6 was obtained from the Plasmodium genomics Resource (plasmodb.org/plasmo/). Subsequently, a three-dimensional model was built following a comparative modelling approach. The model was constructed using SwissPDB Viewer 3.7 following a standard protocol as previously described (Bordoli et al. 2009): (i) load the primary sequence of PfATP6, (ii) search for templates against Protein Data Bank (Berman et al. 2013) and (iii) perform structural alignment and submit it to the Swiss Model Server. In this process, the atomic coordinates of thapsigargin (TG), the natural SERCA inhibitor, were transferred from 1IWO (Toyoshima & Nomura 2002) to build the model. The resultant model was refined by AMBER (Case et al. 2010) using the ff03force field (Salomon-Ferrer et al. 2013). First, the parameters of TG were determined using the antechamber program and AM1-BCC charges, in which the atom types were assigned by the general amber force field (gaff). Second, the complex enzyme (PfATP6-TG) was prepared by the Leap program, constructing the topological and coordinate files. The complex enzyme was minimised in vacuum followed by application of the generalised Born implicit solvent model with 5,000 steep descent steps and 5,000 conjugate gradient steps in each environment (Lee & Duan 2004). Subsequently, 59 structures were constructed and refined by the semiempirical PM6 (Stewart 2007) method (Bikadi & Hazai 2009) implemented in Gaussian 09 W software (Frisch et al. 2009). The ligands (Supplementary Fig. 1) and molecular targets were prepared by MGL Tools software using a standard protocol (Trott & Olson 2010). A grid box was constructed around the ligand and was sufficiently large to cover the entire binding site to limit the docking space (Supplementary Table I). In sequence, TG was re-docked into the built model to evaluate the docking methodology (Supplementary Fig. 2). Two distinct approaches were used, rigid and flexible docking. After the rigid docking, the amino acid residues within 4.5 Å of the experimental ligand were chosen for flexible docking (Supplementary Table II). All docking simulations were carried out using AutoDock Vina software (Trott & Olson 2010). The exhaustiveness was set to 8 to improve the docking search. Finally, DS Visualizer v.4.0 (Accelrys Software Inc, USA) was used to show the docking results of the binding conformations (Leite et al. 2013).

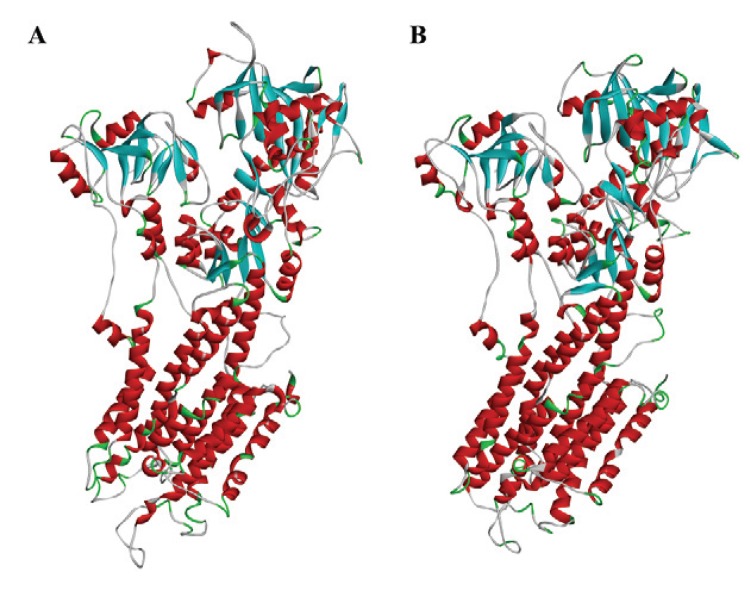

Fig. 1. : three-dimensional structure of the mammalian Ca2+-ATPase 1IWO (A) and parasite PfATP6 model (B).

TABLE. Rigid and flexible binding energy (Kcal/mol) of molecular docking between ent-kaurane diterpenes (8, 9 and 21) and thapsigargin against PfATP6 and 1IWO.

| Compounds | 1IWO | PfATP6 | 1IWO | PfATP6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Rigid | Flexible | ||||

| 8 | -7.6 | -7.7 | -7.1 | -6.6 | |

| 9 | -7.6 | -7.8 | -6.6 | -6.3 | |

| 21 | -9.5 | -8.4 | -7.4 | -6.8 | |

| Thapsigargin | -7.7 | -7.2 | -5.8 | -4.7 | |

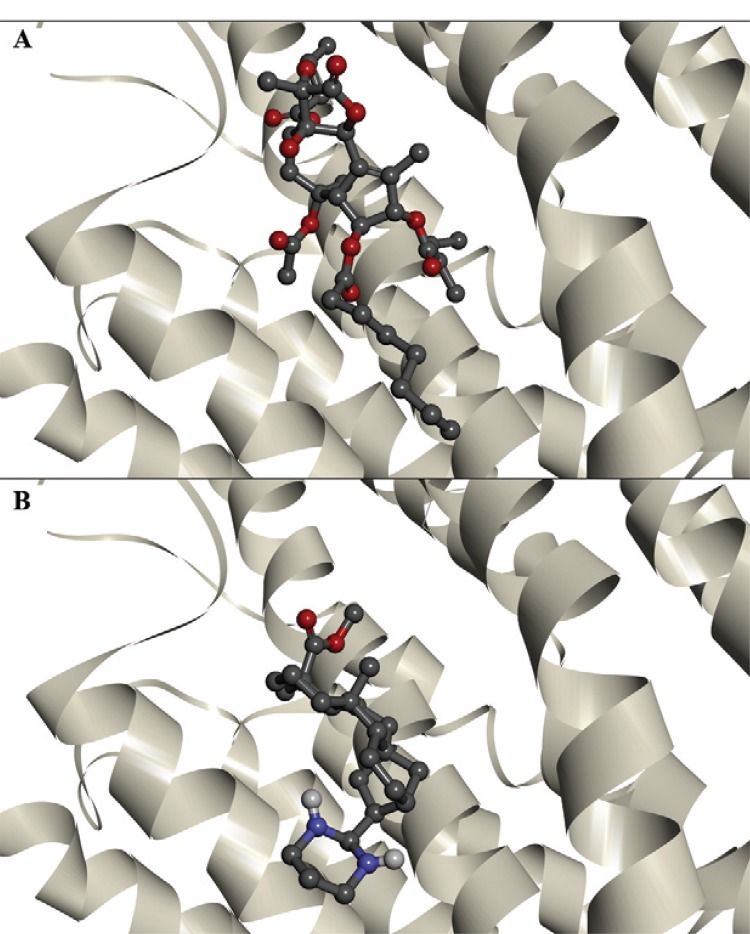

Fig. 2. : interactions of thapsigargin (A) and ent-kaurane diterpene 21 (B) with the PfATP6 binding site.

A preliminary search indicated three main templates on PDB: 2O9J, 3BA6 and 1IWO, with 43%, 49% and 43.5% identity, respectively. All of them were used as a template to build the model (Fig. 1) using Swiss Model Project Mode (Bordoli et al. 2009, Naik et al. 2011).

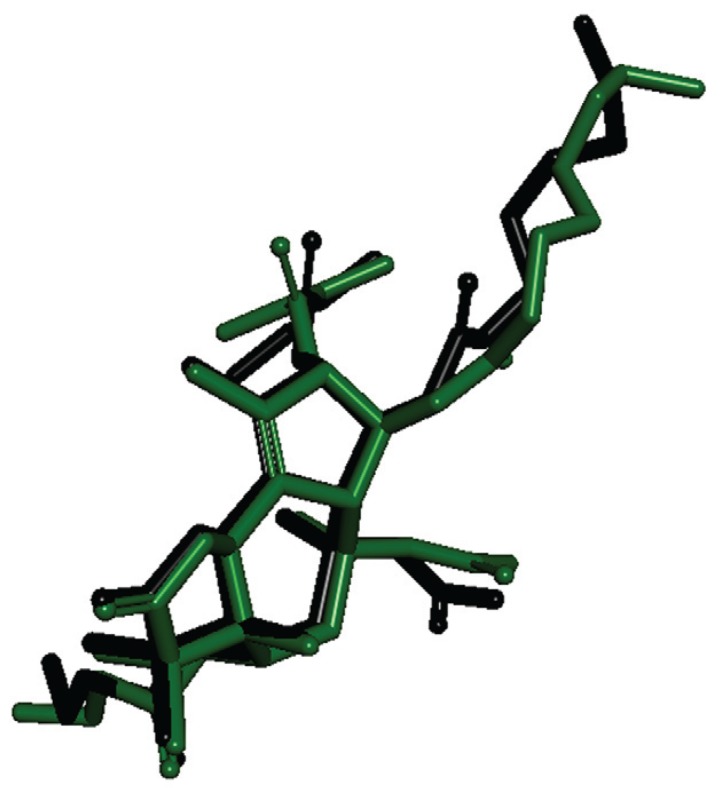

Sequence alignment between PfATP6 and the templates showed a region with low similarity that was removed from PfATP6 to build the model. The PfATP6 refined model was evaluated based on the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) value of the Cα coordinates and the Ramachandran Plot generated by PROCHECK software (Laskowski et al. 1993). Both methods compared against 1IWO showed an RMSD value of 1.61 Å and 87% of residues in the allowed regions; the corresponding percentage for the 1IWO crystal structure was 77.3%. This model is composed of three cytoplasmic domains, denoted as the actuator, phosphorylation and nucleotide binding domains; in addition, there are 10 transmembrane segments denoted as M1 to M10. Initially, the re-docking process showed the structural differences in the natural ligand before and after the molecular docking. The RMSD score was 1.12 Å, indicating that the structures of the molecules are similar to each other. The limit value accepted by the docking approach is 2.0 Å (Trott & Olson 2010). As a result, AutoDock Vina software was used to generate the binding energies of diterpenes and the two enzymes.

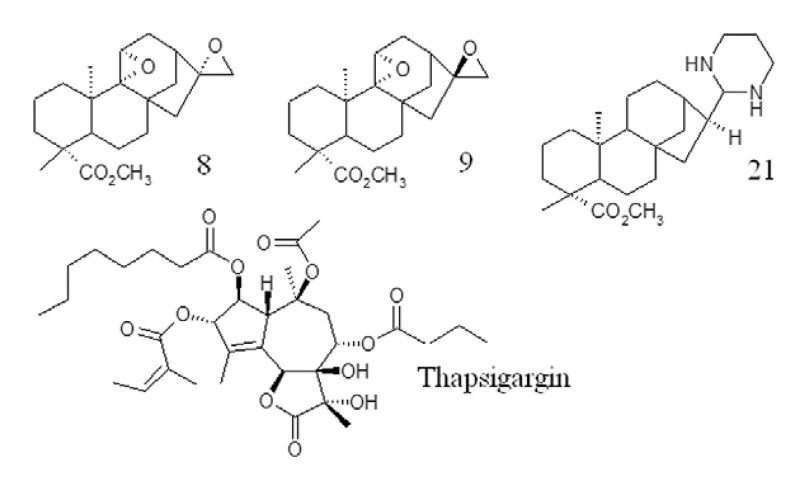

The binding energies of the enzymes PfATP6 and 1IWO, as well as those of ent-kaurane diterpenes (8, 9 and 21) and TG are shown in Table. The three ent-kaurane diterpenes shown in Table were active against P. falciparum in vitro (Batista et al. 2013). Compound 21 was the most active, with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 5.4 µM. Compounds 8 and 9 displayed the highest selective antimalarial activity, with selective index values of 1,238.5 and 810.2, respectively. Compounds 8 and 9 exhibited similar binding energies to those of TG. Compound 21 showed the best docking results against PFATP6 and 1IWO, indicating a stronger interaction with the targets than that of TG, the natural inhibitor. Fig. 2 shows the interaction of TG and compound 21 with the PfATP6 binding site.

These data suggest PfATP6 as a potential target for the semisynthetic antimalarial diterpene epoxides derived from naturally occurring ent-kauranes from W. paludosa. The three ent-kaurane diterpenes presented similar binding energy values to those obtained with mammalian and parasite enzyme models. Further optimisation of these lead compounds may provide a more potent and selective antimalarial drug.

TABLE I. Grid box size and position for both enzymes models.

| Centre position |

Box size |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | x | y | z | ||

| 1IWO | -5.077 | -47.902 | 8.882 | 28 | 26 | 30 | |

| PfATP | -4.857 | -24.528 | 7.832 | 26 | 32 | 28 | |

TABLE II. Flexible amino acids of the active sites from the mammalian and parasite enzymes.

| 1IWO |

PfATP6 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residue | Symbol | Position | Residue | Symbol | Position | |

| Leucine | LEU | 253 | Isoleucine | ILE | 251 | |

| Glutamate | GLU | 255 | Leucine | LEU | 253 | |

| Phenylalanine | PHE | 256 | Phenylalanine | PHE | 254 | |

| Glutamine | GLN | 259 | Glutamine | GLN | 257 | |

| Leucine | LEU | 260 | Leucine | LEU | 258 | |

| Valine | VAL | 263 | Isoleucine | ILE | 261 | |

| Isoleucine | ILE | 761 | Isoleucine | ILE | 748 | |

| Isoleucine | ILE | 765 | Isoleucine | ILE | 752 | |

| Aspartate | ASN | 768 | Aspartate | ASN | 755 | |

| Valine | VAL | 769 | Isoleucine | ILE | 756 | |

| Valine | VAL | 772 | Valine | VAL | 759 | |

| Valine | VAL | 773 | Phenylalanine | PHE | 763 | |

| Phenylalanine | PHE | 776 | Leucine | LEU | 815 | |

| Leucine | LEU | 828 | Isoleucine | ILE | 816 | |

| Isoleucine | ILE | 829 | Leucine | LEU | 821 | |

| Phenylalanine | PHE | 834 | Tyrosine | TYR | 824 | |

| Tyrosine | TYR | 837 | Isoleucine | ILE | 825 | |

| Methionine | MET | 838 | - | - | - | |

Fig. 1. chemical structure of ent-kaurane diterpenes 8, 9, 21 and the natural inhibitor thapsigargin.

Fig. 2. redocking results. In green colour is the crystallographic PDB structure and in black is the docked one. Fig. 1: chemical structure of ent-kaurane diterpenes 8, 9, 21 and the natural inhibitor thapsigargin.

Footnotes

Financial support: FAPEMIG, CNPq

REFERENCES

- Bagnaresi P, Nakabashi M, Thomas AP, Reiter RJ, Garcia CRS. The role of melatonin in parasite biology. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2012;181:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista R, García PA, Castro MA, Corral JMM del, Speziali NL, Varotti FP, Paula RC, García-Fernández LF, Francesch A, San Feliciano A, Oliveira AB. Synthesis, cytotoxicity and antiplasmodial activity of novel ent-kaurane derivatives. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;62:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, Kleywegt GJ, Nakamura H, Markley JL. The future of the protein data bank. Biopolymers. 2013;99:218–222. doi: 10.1002/bip.22132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikadi Z, Hazai E. Application of the PM6 semi-empirical method to modeling proteins enhances docking accuracy of AutoDock. 15J Cheminform. 2009;1 doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordoli L, Kiefer F, Arnold K, Benkert P, Battey J, Schwede T. Protein structure homology modeling using SWISS-MODEL workspace. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1–13. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case D, Darden T, Cheatham TI, Simmerling C, Wang J, Duke R, Luo R, Walker R, Zhang W, Merz K, Roberts B, Wang B, Hayik S, Roitberg A, Seabra G, Kolossvai I, Wong K, Paesani F, Vanicek J, Liu J, Wu X, Brozell S, Steinbrecher T, Gohlke H, Cai Q, Ye X, Hsieh M-J, Cui G, Roe D, Mathews D, Seetin M, Sagui C, Babin V, Luchko T, Gusarov S, Kovalenko A, Kollman P. AMBER. Vol. 11. University of California; San Francisco: 2010. 300 [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Wang Z, Jiang H, Parker D, Wang H, Su X, Cui L. Lack of association of the S769N mutation in Plasmodium falciparum SERCA (PfATP6) with resistance to artemisinins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2546–2552. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05943-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JAJ, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam MJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09. Gaussian Inc; Wallingford CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Furuyama W, Enomoto M, Mossaad E, Kawai S, Mikoshiba K, Kawazu S. An interplay between 2 signaling pathways: melatonin-cAMP and IP3-Ca2+ signaling pathways control intraerythrocytic development of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner MJ, Hall N, Fung E, White O, Berriman M, Hyman RW, Carlton JM, Pain A, Nelson KE, Bowman S, Paulsen IT, James K, Eisen JA, Rutherford K, Salzberg SL, Craig A, Kyes S, Chan M-S, Nene V, Shallom SJ, Suh B, Peterson J, Angiuoli S, Pertea M, Allen J, Selengut J, Haft D, Mather MW, Vaidya AB, Martin DMA, Fairlamb AH, Fraunholz MJ, Roos DS, Ralph SA, McFadden GI, Cummings LM, Subramanian GM, Mungall C, Venter JC, Carucci DJ, Hoffman SL, Newbold C, Davis RW, Fraser CM, Barrell B. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;419:498–511. doi: 10.1038/nature01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna S, Pulcini S, Fatih F, Staines H. Artemisinins and the biological basis for the PfATP6/SERCA hypothesis. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna S, Pulcini S, Moore CM, Teo BH-Y, Staines HM. Pumped up: reflections on PfATP6 as the target for artemisinins. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Lee MC, Duan Y. Distinguish protein decoys by using a scoring function based on a new AMBER force field, short molecular dynamics simulations and the generalized born solvent model. Proteins. 2004;55:620–634. doi: 10.1002/prot.10470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite FHA, Fonseca AL, Nunes RR, Comar M, Jr, Varotti FP, Taranto AG. Malária: dos velhos fármacos aos novos alvos moleculares. Biol Biomed Rep. 2013;2:59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Médebielle M. The medicinal chemistry and drug development of novel antimalarials. Curr Top Med Chem. 2014;14:1635–1636. doi: 10.2174/1568026614666140808152357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meslin B, Beavogui AH, Fasel N, Picot S. Plasmodium falciparum metacaspase PfMCA-1 triggers a z-VAD-fmk inhibitable protease to promote cell death. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LH, Ackerman HC, Su X, Wellems TE. Malaria biology and disease pathogenesis: insights for new treatments. Nat Med. 2013;19:156–167. doi: 10.1038/nm.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik PK, Srivastava M, Bajaj P, Jain S, Dubey A, Ranjan P, Kumar R, Singh H. The binding modes and binding affinities of artemisinin derivatives with Plasmodium falciparum Ca2+-ATPase (PfATP6) J Mol Model. 2011;17:333–357. doi: 10.1007/s00894-010-0726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Alves C. Propelling artemisinin resistance. 1Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;13 doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon-Ferrer R, Case DA, Walker RC. An overview of the amber biomolecular simulation package. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Mol Sci. 2013;3:198–210. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JJP. Optimization of parameters for semiempirical methods. V. Modification of NDDO approximations and application to 70 elements. J Mol Model. 2007;13:1173–1213. doi: 10.1007/s00894-007-0233-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G-B, Sun H, Meng X-B, Hu J, Zhang Q, Liu B, Wang M, Xu H-B, Sun X-B. Aconitine-induced Ca2+ overload causes arrhythmia and triggers apoptosis through p38 MAPK signaling pathway in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;279:8–22. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima C, Nomura H. Structural changes in the calcium pump accompanying the dissociation of calcium. Nature. 2002;418:605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature00944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valderramos SG, Scanfeld D, Uhlemann A, Fidock DA, Krishna S. Investigations into the role of the Plasmodium falciparum SERCA (PfATP6) L263E mutation in artemisinin action and resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3842–3852. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00121-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO - World Health Organization World Malaria Report 2013. 2013 http://who.int/malaria/publications/world_malaria_report_2013/en/ Available from: