Abstract

Chagas disease prevention remains mostly based on triatomine vector control to reduce or eliminate house infestation with these bugs. The level of adaptation of triatomines to human housing is a key part of vector competence and needs to be precisely evaluated to allow for the design of effective vector control strategies. In this review, we examine how the domiciliation/intrusion level of different triatomine species/populations has been defined and measured and discuss how these concepts may be improved for a better understanding of their ecology and evolution, as well as for the design of more effective control strategies against a large variety of triatomine species. We suggest that a major limitation of current criteria for classifying triatomines into sylvatic, intrusive, domiciliary and domestic species is that these are essentially qualitative and do not rely on quantitative variables measuring population sustainability and fitness in their different habitats. However, such assessments may be derived from further analysis and modelling of field data. Such approaches can shed new light on the domiciliation process of triatomines and may represent a key tool for decision-making and the design of vector control interventions.

Keywords: triatomine, domiciliation, intrusion, vector control, ecohealth, integrated vector management

Chagas disease is a major public health problem in the Americas, where it affects seven-eight million people (WHO 2014). The pathogenic agent is a protozoan parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi, mainly transmitted to humans and other mammals through the contaminated faeces of blood-sucking insects called triatomines (Hemiptera: Reduviidae), also known as “kissing bugs”. Control of Chagas disease relies on the treatment of infected patients and prevention of transmission is based mainly on vector control.

Currently, more than 140 species of triatomines are recognised. Over half of them have been shown to be naturally or experimentally infected with T. cruzi, but all are suspected to be able to transmit the parasite (or “serve as vectors”) (Bargues et al. 2010). Nevertheless, not all the triatomine species are considered important vectors of T. cruzi. Vector competence varies considerably between the different species/populations of triatomines and depends on multiple criterions. Among these, the level of domiciliation, which is understood as the level of adaptation to human and its domestic environment, is one of the most important, as it defines the level of human-vector contacts (Dujardin et al. 2002). Indeed, species highly adapted to and able to colonise human dwellings are more likely to actively contribute to the transmission of T. cruzi to humans than species that are only found in sylvatic environment. While the domiciliation of triatomine species/populations is clearly a gradual evolutionary process (Schofield et al. 1999), it has important implications for the design and efficacy of vector control interventions. To date, vector control is mainly achieved through indoor residual insecticide spraying, initially designed to target triatomine species living inside human dwellings and highly adapted to the domestic environment (i.e. domiciliated or domesticated). However, it is becoming increasingly clear that triatomine species presenting lower levels of domiciliation are also playing an important role in T. cruzi transmission to humans and thus need to be taken into account by vector control programs in many regions. The efficacy of conventional insecticide spraying may indeed be directly affected by the level of domiciliation of triatomines and alternative control strategies thus need to be considered against nondomiciliated species/populations. These populations are a potential source of continuous house infestation and post-spraying re-infestation, making the control by insecticide spraying unsustainable, even in areas where transmission is primarily due to highly domiciliated vectors. The level of domiciliation/intrusion of triatomine species thus needs to be clearly defined in operative terms to allow for its precise evaluation and the design of effective vector control interventions.

In this review, we examine how the domiciliation/intrusion level of different triatomine species/populations has been defined and measured and discuss how these concepts may be improved for a better understanding of their ecology and evolution, as well as for the design of more effective control strategies against a large variety of triatomine species.

Level of domiciliation of triatomine species

Triatomine species have for a long time been classified according to their adaptation to human dwellings. According to Lent and Wygodzinsky (1979), the habits of the various species of triatomines allow to divide them into sylvatic and domestic species, with an intermediate category of peridomestic species, which are occasionally attracted into houses, but do not effectively colonise them, and which thus feed on man only occasionally. Dujardin et al. (2002) and Noireau and Dujardin (2010) later refined these definitions and proposed four different categories: sylvatic, intrusive, domiciliary and domestic species (Table I). These definitions have been the most widely accepted and used in the literature for the classification of many triatomine species. In Table II, we summarise how some triatomine species have been classified and the type of data and observations that helped defining their potential association with human habitat. These species/populations were selected based on their epidemiological significance and contribution to T. cruzi transmission to human. As can be observed in Table II, their level of domiciliation appears highly variable depending on the type of data collected by the authors, their own interpretation and the study area. Field collections by manual searches and/or community participation are the most common type of studies, allowing to establish conventional entomological indexes including infestation index (percentage of houses with triatomines), colonisation index (percentage of infested houses with evidence of reproductive cycle: presence of nymphs, but also eggs and/or exuviae), density index (number of triatomines per house) and dispersion index (percentage of localities infested) as the most commonly used (WHO 1991). Infestation and density index have often been considered as indicators of the level of intrusion of a species into the domestic habitat, while the colonisation index can be viewed as a measure of its domiciliation/domestication. More recently, a visitation index has been proposed (percentage of houses visited exclusively by adult triatomines) to evaluate intrusion by adult bugs (Zeledón 2003). As indicated in Table I, the peridomicile is considered as part of the domicile by Dujardin et al. (2002) and Noireau and Dujardin (2010), so that species adapted to peridomestic areas, but not found inside houses, are considered domiciliated/domesticated. However, some of these species have also been classified as peridomestic (e.g., Tritoma sordida) or synanthropic by other authors to differentiate them from those that are also extensively found inside houses.

TABLE I. Classification of triatomine species according to their relationship with human housing.

| Sylvatic species - Strictly found in sylvatic environment. |

|---|

| Intrusive species - Mostly sylvatic, but many adult specimens are reported inside human dwellings, probably attracted there by light or introduced by passive carriage (marsupials, for instance). In this situation, there is no evidence of colonisation (eggs, nymphs and exuviae). |

| Domiciliary species - Characterised by the presence inside houses or peridomiciles of adults and nymphs, eggs and exuviae, which means that the complete cycle of the insect was occurring in domestic environment. The resulting colonies are not very abundant and represent merely a tentative adaptation to houses. It is not necessarily a permanent situation and a domiciliary species can progressively disappear from the houses without any control intervention. |

| Domestic species - The definition includes the aforementioned observations for domiciliary species, with an additional criterion related to the type of geographic extension. It is no more a local, geographically restricted observation, but rather concerns a more widely extended territory with obvious arguments supporting migration by passive carriage. It is, for instance, a discontinuous geographic extension, with gaps apparently unexplained unless the human intervention is admitted. Importantly, sylvatic populations/foci can also exist for the species considered as domestic, as it is well documented even for the highly domesticated emblematic species, Triatoma infestans (Dujardin et al. 2002, Noireau & Dujardin 2010). |

TABLE II. Main triatomine species and their level of domiciliation.

| Species | Country, region | Evidence | Classification | Seroprevalence (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triatoma infestans | Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, southern Peru, Uruguay | Domestic and peridomestic collections of nymphs (and adults) showing high colonisation. Sylvatic foci/populations in the Andean valleys of Bolivia, in the Argentinean, Bolivian and Paraguayan Chaco and in Chile. Very low gene flow and high population genetic structure. Marked reduction of the geographic extension after residual insecticide spraying of dwellings in South America. Domestication appears to have been linked to human activities. Dispersal of the species appears to have been associated with human economic migrations. The species was apparently imported by human migrations in northern Uruguay at the beginning of the XX century and in the Northeast Region of Brazil in the 1970s. | Domestic (with some sylvatic foci/populations) | > 80 in Bolivia | Torrico (1946), Schofield (1988), Bermudez et al. (1993), Noireau et al. (1997b), Brenière et al. (1998, 2013), Panzera et al. (2004), Ceballos et al. (2009), Bacigalupo et al. (2010), Buitrago et al. (2010), Rolón et al. (2011), Waleckx et al. (2011, 2012) |

| Triatoma longipennis and Triatoma barberi | Mexico (Jalisco and Morelos) | High peridomestic infestation (16-60%) and colonisation (75-93%). Domestic intrusion by adults (> 70%). Feeding on humans. Population genetics shows high structuring at the peridomestic level, but high dispersal at larger scale. Significant reinfestation following insecticide spraying. | Peridomestic with domestic intrusion | 1.8 | Ramsey et al. (2003), Brenière et al. (2004, 2007, 2010, 2012) |

| Rhodnius pallescens | Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Panama, Colombia | Infestation by adults (30%), rare colonisation. Possible attraction to houses by light. Frequent blood feeding on humans when inside houses (25-50%). Population genetics shows gene flow between sylvatic and domestic populations. | Sylvatic (palm trees) with some domestic intrusion | 0.2-6.7a | Christensen and de Vasquez (1981), Lopez and Moreno (1995), Vasquez et al. (2004), Calzada et al. (2006), Zeledón et al. (2006), Pineda et al. (2008) |

| Rhodnius prolixus | Guatemala, El Salvador | Significant colonisation of houses. Effective control with indoor insecticide spraying. Frequent blood meals on humans (28%). | Domiciliated (introduced) | 38.8 | Paz-Bailey et al. (2002), Nakagawa et al. (2003a), Sasaki et al. (2003), Cedillos et al. (2012), Hashimoto et al. (2012) |

| R. prolixus | Colombia, Venezuela | High colonisation of houses (domestic habitat) and in palm trees (sylvatic habitat). Population genetics data with variable results: absence of gene flow in Colombia, significant gene flow in Venezuela. Frequent blood meals on humans from domestic populations (53%). | Domiciliated and sylvatic populations | - | Rabinovich et al. (1979), Lopez and Moreno (1995), Feliciangeli et al. (2004, 2007), Fitzpatrick et al. (2008), Angulo et al. (2012) |

| Panstrongylus geniculatus | Brazil, Venezuela, Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, Argentina, Ecuador | Peridomestic and domestic infestation by adults with some seasonality. High levels of intrusion by adult bugs. Rare findings of nymphs and of complete colonies. Housing quality and type not associated with infestation. Risk factors include reduced vegetation cover, reduced presence of animals in the peridomicile combined to increased presence inside dwellings, distance to forest and artificial light. Frequent contact with human and frequent human blood meals reported (up to 60% in adult bugs collected inside dwellings). Reduction of the sexual dimorphism of the isometric size and smaller size of adult specimens collected inside homes in Caracas (Venezuela) suggesting an adaptation to domiciles. | Sylvatic with domestic intrusion Species with potential for domestication | > 15.5 in Venezuelab > 14.2 in Ecuadorc > 1.3 in Boliviad | Chico et al. (1997), Naiff et al. (1998), Valente et al. (1998), Reyes-Lugo and Rodriguez-Acosta (2000), Damborsky et al. (2001), Cáceres et al. (2002), Feliciangeli et al. (2004), Carrasco et al. (2005), Rodríguez-Bonfante et al. (2007), Serrano et al. (2008), Fe et al. (2009), Reyes-Lugo (2009), Aldana et al. (2011), Depickère et al. (2011, 2012) |

| Triatoma brasiliensis | Brazil | Colonies found in peridomestic and sylvatic environments. Colonisation index of 20-59% intradomiciliary and 33-62% peridomiciliary. | Domesticated | - | Lent and Wygodzinsky (1979), Costa et al. (2003) |

| Triatoma sordida e | Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay | Peridomestic collections showing large infestation and colonisation of the peridomiciles. Intrusion (with some seasonality) of adult bugs inside dwellings with anecdotic colonisation. Implicated in re-infestation post-spraying against T. infestans. Population dynamic model supporting insect presence as the outcome both of a local scale “near-to-near” dispersal and infestation from the wild. | Sylvatic with an advanced process of adaptation to human habitat Predominantly peridomestic, without significant colonisation inside dwellings. | > 29.6f | Forattini et al. (1983), Bar et al. (1993, 2002, 2010), Wisnivesky-Colli et al. (1993), Gurtler et al. (1999), Noireau et al. (1999a), Pires et al. (1999), Canale et al. (2000), Falavigna-Guilherme et al. (2004), da Silva et al. (2004), Dias et al. (2005), Cominetti et al. (2011), Roux et al. (2011), Maeda et al. (2012) |

| T. sordida | Eastern Bolivia | Small colonies (3.1 insects/colony) are frequently found inside dwellings (infestation index > 80% and colonisation index > 90%). Up to 70.4% of human blood meals in T. sordida found inside dwellings. Wider panmictic unit than T. infestans. | Domiciliated | > 4 | Noireau et al. (1995, 1997a, 1999b) |

| Rhodnius ecuadoriensis | Ecuador (costal region) | Domestic/peridomestic collections showing infestation and colonisation. Association of domestic infestation with sylvatic infestation. Morphometric analysis indicates flow between sylvatic and domestic habitats. Rapid reinfestation following insecticide spraying. | Sylvatic with capability for domiciliation | 3.6 | Grijalva et al. (2005, 2011, 2012), Black et al. (2009), Villacis et al. (2010) |

| Triatoma dimidiata g | Mexico (Yucatan) | Domestic collections showing seasonal infestation by adults (> 85%) Population dynamics models. Gene flow between sylvatic and domestic habitats from population genetics. Housing quality and type and socioeconomic factors not associated with infestation. Risk factors for infestation include domestic animals, proximity of bushes, light. Rapid re-infestation following insecticide spraying. Colonisation of peridomiciles. | Nondomiciliated | 1-5 | Dumonteil et al. (2002, 2004, 2007, 2013), Gourbière et al. (2008), Pacheco-Tucuch et al. (2012) |

| T. dimidiata g | Belize | Domestic collections showing seasonal infestation by adults. | Nondomiciliated | 1 | Polonio et al. (2009), |

| T. dimidiata g | Mexico (Veracruz) | Domestic collections showing seasonal infestation by adults with some colonisation. Blood meal analysis showing dispersal among habitats. | Nondomiciliated with domiciliation in process | 16.8 | Ramos-Ligonio (2010), Torres-Montero et al. (2012) |

| T. dimidiata g | Guatemala, Costa Rica | Domestic collections of nymphs (and adults) showing high colonisation. Some seasonal variations. Blood meal from domestic hosts only. Housing quality and type and low socioeconomic level associated with infestation. | Domestic | 8.9 | Paz-Bailey et al. (2002), Dorn (2003), Monroy et al. (2003a, b), Nakagawa et al. (2003a, b) |

| Triatoma mexicana | Mexico | Domestic collections showing seasonal infestation by adults. Housing quality and type not associated with infestation. | Intrusive | - | Schettino et al. (2007) |

| Triatoma guasayana | Bolivian and Argentinean Chaco | Peridomestic collections of adults and nymphs. Intrusion of adult bugs inside dwellings without evidence of colonisation. Bugs collected inside dwellings feed on human. Implicated in re-infestation post-spraying against T. infestans. | Sylvatic - Peridomestic, with intrusion of adult bugs inside human dwellings | - | Wisnivesky-Colli et al. (1993), Gajate et al. (1996), Gurtler et al. (1999), Noireau et al. (1999a), Canale et al. (2000), Vazquez-Prokopec et al. (2005) |

| Triatoma sanguisuga | Southern United States of America | Adults occasionally visiting houses. Mainly adults collected inside houses, but some nymphs have also been found in several occasions. Reports of insect bites from T. sanguisuga. Frequent human blood meals. | Essentially sylvatic, with Adults visiting human dwellings | Suspected or incriminated vector for several autochtonous cases of vectorial transmission | Dorn et al. (2007), Zeledón et al. (2012), Waleckx et al. (2014), Garcia et al. (2015) |

a: higher seroprevalence may also be attributed to T. dimidiata present in this region; b: seroprevalence may also be attributed to R. prolixus present in the same area (mixed colonies) as reported by Feliciangeli et al. (2004); c: seroprevalence may also be attributed to Rhodnius pictipes and Rhodnius robustus present in the same area as reported by Chico et al. (1997); d: seroprevalence may also be attributed to Rhodnius rufotuberculatus present in the same area as reported by Depickère et al. (2011); e: species complex with two recognised cryptic species, T. sordida and Triatoma garciabeci (T. sordida group 2); f: seroprevalence may also be attributed to T. infestans present in the same area as reported by Bar et al. (2002); g: species complex.

Population genetics studies based on morphometric and molecular markers are also commonly used. Phylogeographic studies have been used to understand the general distribution of species over wide geographic areas and finer scale studies have focused on evaluating the relationships among populations from different habitats (Gourbière et al. 2012). A high gene flow between populations found inside dwellings and sylvatic environment (and the concomitant lack of population genetic structure - i.e., panmixia) is indicative of an elevated dispersal of bugs between habitats, hence a strongly intrusive behaviour. Conversely, a low gene flow resulting in the genetic differentiation of domestic and sylvatic populations suggests a significant domiciliation/domestication of a population. These approaches have been extensively used to assess the population genetic structure of several species (Table II).

Interestingly, based on the observation of a reduced sexual dimorphism in domesticated populations compared to sylvatic ones, Dujardin et al. (1999) proposed that morphometry may be used as an indicator of the level of adaptation of a species to domestic habitat. However, these observations were not associated with a clear measure of adaptation or fitness of the populations to the domestic habitat.

The data presented in Table II indicate that the classification of triatomine association with human habitat according to current definitions (Table I) is sometimes subjective, depending on the type of data available to establish the nature of the infestation process and this may have important implications for an effective vector control. Indeed, while very few species have been able to reach domestication [estimated at less than 5% of all species following Noireau and Dujardin (2010)], most show very variable capability to invade human housing. It is clear that more objective (and quantitative) criteria are needed to describe this process. We next focus on three triatomine species that have been extensively studied to evaluate additional criteria which may be helpful for a better understanding of infestation.

Case studies

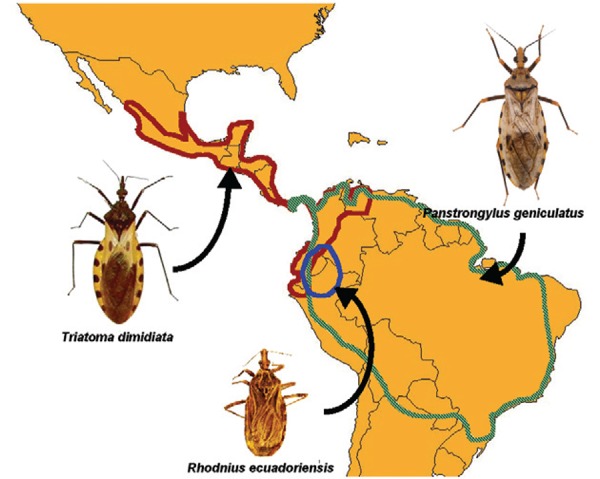

Triatoma dimidiata - T. dimidiata is one of the most important vector of T. cruzi, distributed from central Mexico throughout Central America, to Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Peru (Dorn et al. 2007) (Figure). It is actually a species complex, although the exact number of taxonomic groups to be considered is still debated (Bargues et al. 2008, Dorn et al. 2009, Herrera-Aguilar et al. 2009, Monteiro et al. 2013). This species complex presents highly variable levels of adaptation to humans housing, depending of the geographic region, but possibly also depending on the taxonomic group.

Geographic distribution of T. dimidiata, P. geniculatus and R. ecuadoriensis.

In Guatemala, populations are well domesticated as evidenced by bug collections throughout the country showing high infestation and colonisation indexes (Monroy et al. 2003a, b, Nakagawa et al. 2005). Housing quality and type are key factors affecting domestic colonisation/infestation and in particular poor wall plastering, which may offer a favourable habitat for bugs (Bustamante et al. 2009). Population genetics studies showed some conflicting results, with limited gene flow in agreement with domestication in some cases, but also significant gene flow between sylvatic and domestic populations, suggesting dispersal (Calderon et al. 2004). The analysis of the genetic structure of the population in a single house further showed a great genetic heterogeneity suggesting polyandry and/or high levels of migration of the vector (Melgar et al. 2007).

Vector control with insecticide spraying has been relatively effective in Guatemala, although some re-infestation has been occurring (Nakagawa et al. 2003b, Hashimoto et al. 2006). Dispersing sylvatic bugs may contribute to re-infestation (Monroy et al. 2003b), as well as to the seasonal variations in infestation that have been observed, but the importance of sylvatic populations in domestic infestation is still unclear. More recent studies suggest that integrated and community-based interventions may provide a better and more sustainable control of T. dimidiata in this region (Monroy et al. 2012, Pellecer et al. 2013, Bustamante et al. 2014, de Urioste-Stone et al. 2015).

On the other hand, in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, T. dimidiata populations are one of the best-characterised examples of a nondomiciliated but intrusive vector. Initial observations indicated that adult T. dimidiata transiently infests houses on a seasonal basis during the months of March-July (Dumonteil et al. 2002, 2009, Guzman-Tapia et al. 2007, Payet et al. 2009). This infestation is responsible for a seroprevalence of T. cruzi infection in humans of about 1-5% (Guzman-Bracho et al. 1998, Sosa-Estani et al. 2008, Gamboa-León et al. 2014). Population genetics and mathematical models describing the population stage-structure as well as the dispersal of T. dimidiata indicate that house infestation is caused by the seasonal dispersal of bugs from peridomestic and sylvatic habitats surrounding the villages, while triatomine reproduction in the domestic habitat (i.e., domiciliation) plays a negligible role (Dumonteil et al. 2007, Gourbière et al. 2008, Barbu et al. 2009). Indeed, while nymphs may occasionally be found in houses (Dumonteil et al. 2002), the low colonisation index (< 20%) rather suggests unsuccessful attempts at colonising the domestic habitat by intruding bugs, possibly because of insufficient feeding (Payet et al. 2009). Such poor feeding in the domestic habitat may be associated with sleeping habits in the region, as hammocks were found to complicate bug access to a host and particularly for nymphs (E Waleckx et al., unpublished observations).

Further modelling and field investigations of the spatiotemporal infestation patterns indicated that houses located in the periphery of the villages are significantly more infested than those located in the village centre (Slimi et al. 2009, Barbu et al. 2010, 2011, Ramirez-Sierra et al. 2010). Attraction by public lights also contributes significantly to transient infestation (Pacheco-Tucuch et al. 2012), together with the presence of domestic animals such as dogs and chickens, while housing type and quality or socioeconomic level do not play a significant role (Dumonteil et al. 2013). Inhabitants are rather familiar with this seasonal invasive behaviour of T. dimidiata (Rosecrans et al. 2014).

In this situation, effective insecticide spraying would require yearly applications within a narrow time window of less than two months, which would be difficult to implement and clearly unsustainable, while insect screens may offer a sustainable and effective alternative (Dumonteil et al. 2004, Barbu et al. 2009, 2011, Ferral et al. 2010). Environmental management of the peridomiciles, i.e., the elimination of peridomestic colonies by cleaning and insecticide spraying, was found to partially but durably reduce house infestation and may thus be an important component of vector control interventions (Ferral et al. 2010). Spatially targeted interventions may allow for further optimisation of vector control (Barbu et al. 2011). Based on this, an ecohealth approach has recently been tested at a small scale, based on a community-based installation of window insect screens in bedrooms, with or without education for improved peridomestic animal management (Waleckx et al. 2015). Such integrated control strategy seems very promising for the sustainable control of this intrusive vector in the Yucatan Peninsula.

Analysis of the genetic structure of T. dimidiata in Boyaca, Colombia, also indicated a low level of genetic differentiation and a high level of exchanges of bugs among domestic, peridomestic and sylvatic habitats (Ramirez et al. 2005), suggesting that the situation observed in the Yucatan Peninsula and Belize (Polonio et al. 2009) may also be occurring in parts of Colombia.

Panstrongylus geniculatus - P. geniculatus is one of the most widely distributed species of triatomine in South and Central America (Leite et al. 2007) (Figure). It is commonly considered as a sylvatic species frequently flying to human habitations, probably attracted by light (Lent & Wygodzinsky 1979). The intrusion of adult bugs is well documented and collections of only adult specimens inside dwellings have been reported in different areas (particularly in the Amazon Basin, but not only) in Venezuela (Serrano et al. 2008, Reyes-Lugo 2009), Colombia (Angulo et al. 2012), Brazil (Naiff et al. 1998, Fe et al. 2009, Maeda et al. 2012), Peru (Cáceres et al. 2002, Torres & Cabrera 2010), Bolivia (Depickère et al. 2011, 2012), 2012) and Argentina (Damborsky et al. 2001). The main factors that cause P. geniculatus to increasingly invade human dwellings seem to be the devastation of the primary forests (for example for the construction of human dwellings), overhunting and burning of forests, all of which destroying the triatomines’ natural habitat and causing them to seek alternative shelter and hosts (Valente 1999). Although the intrusion of adult bugs and the absence of colonisation seem to be the most common behaviours of this species, some events of domicile colonisation have also been reported. Indeed, there are some reports of nymphal stages and colonies of P. geni- culatus found in peridomiciles and/or inside dwellings in Venezuela (Reyes-Lugo & Rodriguez-Acosta 2000, Feliciangeli et al. 2004, Rodríguez-Bonfante et al. 2007), Brazil (Valente et al. 1998), Ecuador (Chico et al. 1997), Bolivia (Depickère et al. 2011) and Colombia (Maestre-Serrano & Eyes-Escalante 2012). Consequently, the species is now increasingly considered as a species in the process of domiciliation/domestication.

Interestingly, Aldana et al. (2011) found that the sexual dimorphism of the isometric size of adults of P. geniculatus was reduced in bugs collected in domestic environment compared to bugs collected in sylvatic environments in Venezuela. In this study, the authors considered that this may be an indicator of domiciliation, as proposed by Dujardin et al. (1999).

Additionally, there are reports of people being attacked by this bug species inside their homes (Valente et al. 1998, Reyes-Lugo & Rodriguez-Acosta 2000, Carrasco et al. 2005, Reyes-Lugo 2009), which has been confirmed by blood meal analyses (Feliciangeli et al. 2004, Carrasco et al. 2005). P. geniculatus has also been increasingly identified as the likely responsible vector in some acute cases of Chagas disease (Vega et al. 2006, Valente et al. 2009, Cabrera et al. 2010, Rios et al. 2011) in South America. Consequently, it is given more consideration as a major vector of Chagas disease by vector control programs, but no strategy has been specifically defined against this vector and current data indicate that a more precise evaluation of its level of intrusion inside houses and of its potential for domiciliation/domestication is clearly needed so that these aspects may be taken into account for the design of effective and sustainable vector control interventions against P. geniculatus.

Rhodnius ecuadoriensis – R. ecuadoriensis is distributed from southern Colombia throughout eastern Ecuador and in northern Peru, where it is considered an important vector of T. cruzi (Figure). However, studies on its ecology and vectorial role have been limited and report somewhat conflicting results. The species was initially described infesting and colonising domiciles in Peru and Ecuador and this was quickly extended to the peridomestic habitat and R. ecuadoriensis was labelled as a synanthropic species (Abad-Franch et al. 2002, Cuba Cuba et al. 2002, 2003, Grijalva et al. 2005), in the sense that it was domiciliated/domesticated. Frequent blood feeding on humans from these bug populations was also reported (Abad-Franch et al. 2002). However, further studies showed that R. ecuadoriensis was also abundant in sylvatic habitats, principally associated with palm trees, as most Rhodnius species (Abad-Franch et al. 2000, 2005, Grijalva & Villacis 2009, Suarez-Davalos et al. 2010, Grijalva et al. 2012), raising the question of the relationship between its sylvatic and domestic/peridomestic populations. The initial hypothesis was that synanthropic populations were relatively isolated from sylvatic ones, at least in southern Ecuador and northern Peru, raising the possibility that synanthropic populations may be eliminated by insecticide spraying interventions (Abad-Franch et al. 2001, Cuba Cuba et al. 2002). However, such interventions were met with limited success, as a significant re-infestation was observed following spraying (Grijalva et al. 2011), indicating that vector control may result much more challenging.

Morphometric analysis of wing size and shape supported the presence of extensive exchanges of bugs among habitats in coastal Ecuador, but conversely suggested a significant population structuring in southern Ecuador, with a low dispersal and exchange of bugs among habitats (Villacis et al. 2010). Such variability may be due to ecological differences in these regions, but may also reflect intrinsic differences in behaviour linked to genetic differences within the species. Indeed, two phylogenetic clades have been described in R. ecuadoriensis based on the cytochrome B mitochondrial marker (Abad-Franch & Monteiro 2005) and significant morphometric differences have been observed as well (Villacis et al. 2010). The level of domiciliation of R. ecuadoriensis may thus be variable, being more domiciliated in southern Ecuador and northern Peru and more sylvatic and intrusive in eastern Ecuador, although the factors underlying these differences remain unclear.

As evidenced by the difficulties in controlling this vector with indoor insecticide spraying (Grijalva et al. 2011), defining the exact level of domiciliation/intrusion of the different populations of R. ecuadoriensis is still needed to define effective vector control interventions in the different regions where this species is present.

Revisiting the domiciliation process: toward operational definitions for vector control

The classification of triatomine species/populations into sylvatic, intrusive, domiciliary and domestic proposed earlier (Noireau & Dujardin 2010) is useful from a general evolutionary perspective. However, as evidenced in Table II and the examples detailed above, these theoretical concepts may be challenged by the realities of vector control.

A major limitation of current criteria defining the association of triatomine with human habitat is that these are essentially qualitative (Table I) and do not rely on quantitative variables, leaving much to the subjective interpretation of the data. This and the apparent regional variability of domiciliation level of the different populations of a same species may be the main reasons why some species/populations are classified differently by authors as shown in Table II. For most species, a quantification of the ability of species/population to reproduce and adapt in human habitat is needed for effective vector control. Indeed, indoor residual insecticide spraying has been very effective in only two settings: domestic Triatoma infestans in most of the Southern Cone countries and domestic R. prolixus in Central America. Thus, several Southern Cone countries and regions have been certified (or are in the process) as free of T. infestans vectorial transmission and similarly in Central America with R. prolixus (Schofield et al. 2006). This success is largely due to the fact that these T. infestans and R. prolixus populations were exclusively domesticated and introduced in these countries (i.e., with no sylvatic populations), which considerably limited the possibilities for re-infestation following spraying. On the other hand, the control of most other triatomine species/populations has been more challenging, mostly because domestic populations remain connected to sylvatic populations, which can then contribute to re-infestation. The same fact mostly explains why, in areas where T. infestans sylvatic foci exist, the elimination of house infestation is jeopardised. Indeed, while T. infestans has been described as one of the most domesticated triatomine species, the persistence and re-infestation of houses by this species in the Andean region can be attributed, at least in part, to the dispersal of bugs from sylvatic populations (Noireau et al. 2005, Ceballos et al. 2011, Brenière et al. 2013). In the Andes, these have been found to be well established in sylvatic habitats over an extensive region (Buitrago et al. 2010, Waleckx et al. 2011, Bremond et al. 2014) and to feed on humans relatively frequently (Buitrago et al. 2013). Dispersal of these sylvatic bugs towards houses for re-infestation will thus need to be taken into account for an effective control, even in the case of this emblematic highly domesticated species.

From the perspective of vector control, it is thus of major importance to determine precisely three aspects of the relationship of triatomines with humans: (i) the presence of sylvatic populations of triatomines, (ii) the level of intrusion of these sylvatic populations in peridomiciles and inside domiciles and (iii) the level of domiciliation or domestication in peridomiciles and inside houses. Indeed, this information should guide vector control program in their decision-making over the design of evidence-based interventions to ensure their effectiveness. A significant domiciliation or domestication inside dwellings would suggest that indoor insecticide spraying and/or housing-improvement interventions aimed at reducing the suitability of the domestic habitat would be effective in reducing/eliminating house infestation as was the case with T. infestans (Schofield et al. 2006). On the other hand, a high level of intrusion inside dwellings would rule out indoor insecticide spraying as a key component of vector control, which would rather need to focus on limiting triatomine entry inside houses. Interventions based on window insect screens or insecticide-impregnated curtains (Herber & Kroeger 2003, Barbu et al. 2009, 20, 2011, Ferral et al. 2010, Waleckx et al. 2015) would thus be recommended. In any case, community education should also be considered as part of all vector interventions to strengthen their sustainability. Importantly, long-term entomological surveillance should be implemented to detect potential changes in vector population dynamics due to the adaptation or replacement of vector species, as well as the emergence of insecticide resistance.

Analysis of Table II and of the cases studies presented provides clues to the type of empirical and theoretical data needed to appreciate the levels of intrusion and domiciliation of triatomine species. As can be seen, the primary source of evidences comes from field studies based on timed-manuals collections, traps and sensors and/or community participation to document infestation patterns in different habitats. However, such studies may be misleading if too limited in scope, geographic coverage and sample size, as seen with the initial studies of R. ecuadoriensis, which suggested that it was synanthropic. Additionally to the collections in the domestic habitat, exhaustive searches in peridomestic and sylvatic habitats are needed for a complete description of triatomine distribution. Infestation data at different geographic scales is critical, with in depth studies limited to a small number of villages providing precise data on population structure and demography, complemented with larger scale studies including many villages, to allow for generalisation over large regions. The establishment of the level of domiciliation/intrusion of triatomines in the different habitats should be properly done at the same geographic scale as that of vector control intervention, since species can present regional differences in their level of domiciliation. In addition, while most studies are based on a single time-point, longitudinal studies clearly provide a more complete description of the infestation dynamics and its potential seasonal variations (Dumonteil et al. 2002, Schettino et al. 2007, Payet et al. 2009).

The definitions in Table I are rather subjective and lack clear “thresholds” between the different domiciliation levels to objectively classify the triatomine populations in any of the categories. The classical entomologic indexes mentioned above may be seen as attempts to provide a quantitative evaluation of the domiciliation status of triatomines. However, they do not provide a clear description of the level of adaptation to human habitat. For example, while the colonisation index is often taken as indicative of the domiciliation/domestication of a species/population, it actually falls short of demonstrating the occurrence of the complete reproductive cycle of the bugs, nor of its sustainability over time. Also, nymphs may reach houses by walking or may have emerged from eggs released by a visiting female. Similarly, the visitation index does not take into account seasonal intrusion or may be biased by a low detection of nymphs.

Population genetics analysis leading to the characterisation of population genetic structure, population assignment and assessment of gene flow can also shed some light on bug dispersal among habitat and on domiciliation (Gourbière et al. 2012). However, these studies remain costly and technically challenging and more appropriate for basic research than for vector control programs. It is also worth noting that the genetic structure strictly depends on the molecular clock of the genetic markers used and these needs to be carefully selected to provide reliable information. Indeed, conflicting results may be obtained depending on the methods used to infer gene flow among populations, as observed for T. infestans (Brenière et al. 1998). Similarly, other types of molecular studies, such as the identification of blood feeding sources and profiles are central to further evaluate and quantify the risks of transmission of T. cruzi to humans (Dumonteil et al. 2013, Waleckx et al. 2014), but may be limited to a research setting. On the other hand, the analysis of infestation risk factors may be useful and can be applied to entomological data from very large number of houses from surveillance program (Campbell-Lendrum et al. 2007), but the evidence provided is very indirect, so often insufficient to determine the level of intrusion/domiciliation.

Finally, the modelling of vector population dynamics and T. cruzi transmission provides a very powerful way of analysing field collection data, as it allows quantifying the effects of bug dispersal (i.e., intrusion) and demography (i.e., domiciliation) on the infestation process and transmission of T. cruzi, as well as anticipating the potential efficacy of control strategies when empirical approaches are difficult for practical, financial or ethical reasons. An interesting example in the field is the modelling of T. dimidiata source-sink dynamics in the Yucatan Peninsula, that provided quantitative evidences that although nymph stages were occasionally detected inside houses, such limited colonisation was not compatible with an effective domiciliation, as domestic populations were not self-sustainable, but rather strictly depended on seasonal intrusion of adult bugs (Gourbière et al. 2008, Barbu et al. 2009, 2010, 2011). Such models can easily be adjusted to a variety of bug collection data from field studies [see Nouvellet et al. (2015) for a review] and sensitivity analysis can provide (theoretical) thresholds for both intrusion/domiciliation of bugs populations, as well as for the transmission of T. cruzi to humans (Rascalou et al. 2012, Nouvellet et al. 2013). Setting up more (“Leslie” or “Lefkovitch”) (Caswell 2001) matrix models of triatomine’s life history and population dynamics would also lay the foundations for micro-evolutionary studies. In fisherian optimality approaches (Roff 2010), this type of modelling indeed allows identifying the fitness value of a given strategy according to the complete life history it corresponds to. Direct comparisons between the fitness values of alternative strategies then provide an objective and quantitative way to predict the evolutionary “optimal” strategy. More elaborated description of the meta-population dynamics (Gourbière & Gourbière 2002), the nonlinear ecological (e.g., competitive) interactions and/or the genetic determinism of the strategies can be accounted in identifying evolutionary dynamics (Meszena et al. 2001, Dieckmann et al. 2002), potentially leading to more complex insect life-history evolutionary dynamics according to frequency and density-dependent fitness values (Gourbière & Menu 2009). These approaches are barely used to understand triatomine’s evolution [but see Menu et al. (2010) and Pelosse et al. (2013)], while they could provide critical quantitative insights into the domiciliation of triatomine or their adaptive response to control interventions, two issues that are critical to our understanding of the ecology, evolution and control of Chagas disease.

Concluding remarks

While domiciliation is clearly a gradual evolutionary process, we argued here that more precise evaluations of the level of adaptation of triatomine species to human habitats are needed for the optimisation of vector control. While only a few species have been able to effectively adapt to human housing, most remain connected to sylvatic populations and show variable levels of intrusion. Such behaviour requires the design of specific vector control interventions targeting this intrusion process, rather than insecticide spraying which only targets domesticated triatomine populations. Most current approaches used to assess triatomine association with human habitat, based on field and laboratory studies, provide insufficient information on the level of domestic adaptation of triatomines. Further analysis and modelling of field data can provide quantitative estimates of population persistence and fitness, shed new light on the domiciliation process of triatomine and may represent a key tool for decision-making and the design of vector control interventions.

Funding Statement

Financial support: UNDP/World Bank/WHO-TDR/IDRC (A90276)

Footnotes

Financial support: UNDP/World Bank/WHO-TDR/IDRC (A90276)

REFERENCES

- Abad-Franch F, Aguilar VHM, Paucar CA, Lorosa ES, Noireau F. Observations on the domestic ecology of Rhodnius ecuadoriensis (Triatominae) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:199–202. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad-Franch F, Monteiro FA. Molecular research and the control of Chagas disease vectors. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2005;77:437–454. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652005000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad-Franch F, Noireau F, Paucar A, Aguilar HM, Carpio C, Racines J. The use of live-bait traps for the study of sylvatic Rhod- nius populations (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in palm trees. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:629–630. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad-Franch F, Palomeque FS, Aguilar HM, Miles MA. Field ecology of sylvatic Rhodnius populations (Heteroptera, Triatominae): risk factors for palm tree infestation in western Ecuador. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:1258–1266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad-Franch F, Paucar CA, Carpio CC, Cuba Cuba CA, Aguilar VHM, Miles MA. Biogeography of Triatominae (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Ecuador: implications for the design of control strategies. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:611–620. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldana E, Heredia-Coronado E, Avendano-Rangel F, Lizano E, Concepcion JL, Bonfante-Cabarcas R, Rodríguez-Bonfante C, Pulido MM. Morphometric analysis of Panstrongylus geniculatus (Heteroptera: Reduviidae) from Caracas city, Venezuela. Biomedica. 2011;31:108–117. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572011000100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo VM, Esteban L, Luna KP. Attalea butyracea palms adjacent to housing as a source of infestation by Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) Biomedica. 2012;32:277–285. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572012000300016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacigalupo A, Torres-Pérez F, Segovia V, García A, Correa JP, Moreno L, Arroyo P, Cattan PE. Sylvatic foci of the Chagas disease vector Triatoma infestans in Chile: description of a new focus and challenges for control programs. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2010;105:633–641. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762010000500006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar ME, Damborsky MP, Oscherov EB, Milano AMF, Avalos G, Wisnivesky-Colli C. Triatomines involved in domestic and wild Trypanosoma cruzi transmission in Concepción, Corrientes, Argentina. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:43–46. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar ME, Oscherov EB, Damborsky MP. Presence of Triatoma sordida Stål, 1859 in Corrientes city urban ecotopes. Rev Saude Publica. 1993;27:117–122. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101993000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar ME, Oscherov EB, Damborsky MP, Borda M. Epidemiology of American trypanosomiasis in the north of Corrientes province, Argentina. Medicina (B Aires) 2010;70:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbu C, Dumonteil E, Gourbière S. Optimization of control strategies for non-domiciliated Triatoma dimidiata, Chagas disease vector in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbu C, Dumonteil E, Gourbière S. Characterization of the dispersal of non-domiciliated Triatoma dimidiata through the selection of spatially explicit models. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbu C, Dumonteil E, Gourbière S. Evaluation of spatially targeted strategies to control non-domiciliated Triatoma dimidiata vector of Chagas disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargues MD, Klisiowicz DR, Gonzalez-Candelas F, Ramsey J, Monroy C, Ponce C, Salazar-Schettino PM, Panzera F, Abad F, Sousa OE, Schofield C, Dujardin JP, Guhl F, Mas-Coma S. Phylogeography and genetic variations of Triatoma dimidiata, the main Chagas disease vector in Central America and its position within the genus Triatoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargues MD, Schofield CJ, Dujardin JP. Classification and phylogeny of the Triatominae. In: Telleria J, Tibayrenc M, editors. American trypanosomiasis Chagas disease - One hundred years of research. Elsevier; Burlington: 2010. pp. 117–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez H, Balderrama F, Torrico F. Identification and characterization of sylvatic foci of Triatoma infestans in central Bolivia. 371Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49(Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- Black CL, Ocana-Mayorga S, Riner DK, Costales JA, Lascano MS, Arcos-Teran L, Preisser JS, Seed JR, Grijalva MJ. Seroprevalence of Trypanosoma cruzi in rural Ecuador and clustering of seropositivity within households. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:1035–1040. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.08-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremond P, Salas R, Waleckx E, Buitrago R, Aliaga C, Barnabé C, Depickère S, Dangles O, Brenière SF. Variations in time and space of an Andean wild population of T. infestans at a microgeographic scale. 164Parasit Vectors. 2014;7 doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenière SF, Bosseno MF, Gastelum EM, Gutierrez MMS, Monges MJK, Salas JHB, Paredes JJR, Kasten FJL. Community participation and domiciliary occurrence of infected Meccus longipennis in two Mexican villages in Jalisco state. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:382–387. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenière SF, Bosseno MF, Magallon-Gastelum E, Ruvalcaba EGC, Gutierrez MS, Luna ECM, Basulto JT, Mathieu-Daude F, Walter A, Lozano-Kasten F. Peridomestic colonization of Triatoma longipennis (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) and Triatoma barberi (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) in a rural community with active transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi in Jalisco state, Mexico. Acta Trop. 2007;101:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenière SF, Bosseno MF, Vargas F, Yaksic N, Noireau F, Noel S, Dujardin JP, Tibayrenc M. Smallness of the panmictic unit of Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) J Med Entomol. 1998;35:911–917. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/35.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenière SF, Pietrokovsky S, Gastelum EM, Bosseno MF, Soto MM, Ouaissi A, Kasten FL, Wisnivesky-Colli C. Feeding patterns of Triatoma longipennis Usinger (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) in peridomestic habitats of a rural community in Jalisco state, Mexico. J Med Entomol. 2004;41:1015–1020. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.6.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenière SF, Salas R, Buitrago R, Bremond P, Sosa V, Bosseno MF, Waleckx E, Depickère S, Barnabé C. Wild populations of Triatoma infestans are highly connected to intra-peridomestic conspecific populations in the Bolivian Andes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenière SF, Waleckx E, Magallon-Gastelum E, Bosseno MF, Hardy X, Ndo C, Lozano-Kasten F, Barnabé C, Kengne P. Population genetic structure of Meccus longipennis (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae), vector of Chagas disease in west Mexico. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitrago R, Bosseno MF, Waleckx E, Bremond P, Vidaurre P, Zoveda F, Brenière SF. Risk of transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi by wild Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Bolivia supported by the detection of human blood meals. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;19:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitrago R, Waleckx E, Bosseno MF, Zoveda F, Vidaurre P, Salas R, Mamani E, Noireau F, Brenière SF. First report of widespread wild populations of Triatoma infestans (Reduviidae, Triatominae) in the valleys of La Paz, Bolivia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:574–579. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante DM, Urioste-Stone SM, Juarez JG, Pennington PM. Ecological, social and biological risk factors for continued Trypanosoma cruzi transmission by Triatoma dimidiata in Guatemala. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante DM, Monroy C, Pineda S, Rodas A, Castro X, Ayala V, Quinones J, Moguel B, Trampe R. Risk factors for intradomiciliary infestation by the Chagas disease vector Triatoma dimidiata in Jutiapa, Guatemala. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25(1):83–92. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009001300008. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera R, Vega S, Caceres AG, Ramal AC, Alvarez C, Ladera P, Pinedo R, Chuquipiondo G. Epidemiological investigation of an acute case of Chagas disease in an area of active transmission in Peruvian Amazon Region. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:269–272. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652010000500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres AG, Troyes L, Gonzáles-Pérez A, Llontop E, Bonilla C, Murias E, Heredia N, Velásquez C, Yáñez C. Enfermedad de Chagas en la región nororiental del Perú. I. Triatominos (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) presentes en Cajamarca y Amazonas. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2002;19:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Calderon CI, Dorn PL, Melgar S, Chavez JJ, Rodas A, Rosales R, Monroy CM. A preliminary assessment of genetic differentiation of Triatoma dimidiata (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Guatemala by random amplification of polymorphic DNA-polymerase chain reaction. J Med Entomol. 2004;41:882–887. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.5.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada JE, Pineda V, Montalvo E, Alvarez D, Santamaria AM, Samudio F, Bayard V, Caceres L, Saldana A. Human trypanosome infection and the presence of intradomicile Rhodnius pallescens in the western border of the Panama Canal, Panama. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:762–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Lendrum D, Angulo VM, Esteban L, Tarazona Z, Parra GJ, Restrepo M, Restrepo BN, Guhl F, Pinto N, Aguilera G, Wilkinson P, Davies CR. House-level risk factors for triatomine infestation in Colombia. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:866–872. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canale DM, Cecere MC, Chuit R, Gurtler RE. Peridomestic distribution of Triatoma garciabesi and Triatoma guasayana in north-west Argentina. Med Vet Entomol. 2000;14:383–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco HJ, Torrellas A, Garcia C, Segovia M, Feliciangeli MD. Risk of Trypanosoma cruzi I (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) transmission by Panstrongylus geniculatus (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Caracas (metropolitan district) and neighboring states, Venezuela. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:1379–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caswell H. Matrix population models: construction, analysis and interpretation. 2nd. Sinauer Associates Inc; Sunderland: 2001. 722 [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos LA, Piccinali RV, Berkunsky I, Kitron U, Gurtler RE. First finding of melanic sylvatic Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) colonies in the Argentine Chaco. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:1195–1202. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos LA, Piccinali RV, Marcet PL, Vazquez-Prokopec GM, Cardinal MV, Schachter-Broide J, Dujardin JP, Dotson EM, Kitron U, Gurtler RE. Hidden sylvatic foci of the main vector of Chagas disease Triatoma infestans: threats to the vector elimination campaign? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedillos RA, Romero JE, Sasagawa E. Elimination of Rhod- nius prolixus in El Salvador, Central America. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107:1068–1069. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762012000800018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chico HM, Sandoval C, Guevara EA, Calvopiña HM, Cooper PJ, Reed SG, Guderian RH. Chagas disease in Ecuador: evidence for disease transmission in an indigenous population in the Amazon Region. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92:317–320. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761997000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen HA, Vasquez AM. Host feeding profiles of Rhodnius pallescens (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in rural villages of central Panama. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:278–283. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cominetti MC, Andreotti R, Oshiro ET, Dorval MEMC. Epidemiological factors related to the transmission risk of Trypanosoma cruzi in a Quilombola community, state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2011;44:576–581. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822011000500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa J, Almeida CE, Dotson EM, Lins A, Vinhaes M, Silveira AC, Beard CB. The epidemiologic importance of Triatoma brasiliensis as a Chagas disease vector in Brazil: a revision of domiciliary captures during 1993-1999. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:443–449. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuba Cuba CA, Abad-Franch F, Rodríguez JR, Vásquez FV, Velásquez LP, Miles MA. The triatomines of northern Peru with emphasis on the ecology and infection by trypanosomes of Rhodnius ecuadoriensis (Triatominae) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:175–183. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuba Cuba CA, Vargas F, Roldan J, Ampuero C. Domestic Rhodnius ecuadoriensis (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) infestation in northern Peru: a comparative trial of detection methods during a six-month follow-up. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2003;45:85–90. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652003000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva RA, Sampaio SMP, Poloni M, Koyanagui PH, Carvalho ME, Rodrigues VLCC. Pesquisa sistemática positiva e relação com conhecimento da população de assentamento e reassentamento de ocupação recente em área de Triatoma sordida (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) no estado de São Paulo, Brasil. Cad Saude Publica. 2004;20:555–561. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2004000200024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damborsky MP, Bar ME, Oscherov EB. Detección de triatominos (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) en ambientes domésticos y extradomésticos, Corrientes, Argentina. Cad Saude Publica. 2001;17:843–849. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2001000400018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urioste-Stone SM, Pennington PM, Pellecer E, Aguilar TM, Samayoa G, Perdomo HD, Enríquez H, Juárez JG. Development of a community-based intervention for the control of Chagas disease based on peridomestic animal management: an eco-bio-social perspective. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109:159–167. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/tru202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depickère S, Durán P, López R, Chávez T. Presence of intra- domicile colonies of the triatomine bug Panstrongylus rufotuberculatus in Muñecas, La Paz, Bolivia. Acta Trop. 2011;117:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depickère S, Duran P, Lopez R, Martinez E, Chavez T. After five years of chemical control: colonies of the triatomine Eratyrus mucronatus are still present in Bolivia. Acta Trop. 2012;123:234–238. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias JCP, Vieira EP, Tadashi H, Azeredo BVM. Nota sobre o uso de bio-sensores “Maria” nas ações de vigilância entomológica contra a doença de Chagas ao norte de Minas Gerais. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:377–382. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822005000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann U, Metz JAJ, Sabelis MW, Sigmund K. Adaptive dynamics of infectious diseases: in pursuit of virulence management. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2002. 463 [Google Scholar]

- Dorn PL, Calderon C, Melgar S, Moguel B, Solorzano E, Dumonteil E, Rodas A, Rua N, Garnica R, Monroy C. Two distinct Triatoma dimidiata (Latreille, 1811) taxa are found in sympatry in Guatemala and Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn PL, Melgar S, Rouzier V, Gutierrez A, Combe C, Rosales R, Rodas A, Kott S, Salvia D, Monroy CM. The Chagas vector, Triatoma dimidiata (Hemiptera: Reduviidae), is panmictic within and among adjacent villages in Guatemala. J Med Entomol. 2003;40:436–440. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-40.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn PL, Monroy C, Curtis A. Triatoma dimidiata (Latreille, 1811): a review of its diversity across its geographic range and the relationship among populations. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin JP, Schofield CJ, Panzera F. Los vectores de la enfermedad de Chagas. Académie Royale des Sciences d’Outre-Mer; Bruxelles: 2002. 189 [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin JP, Steindel M, Chavez T, Machane M, Schofield CJ. Changes in the sexual dimorphism of triatominae in the transition from natural to artificial habitats. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:565–569. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761999000400024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumonteil E, Ferral J, Euan-García M, Chavez-Nuñez L, Ramirez-Sierra MJ. Usefullness of community participation for the fine-scale monitoring of non-domiciliated triatomines. J Parasitol. 2009;95:469–471. doi: 10.1645/GE-1712.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumonteil E, Gourbière S, Barrera-Perez M, Rodriguez-Felix E, Ruiz-Piña H, Baños-Lopez O, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Menu F, Rabinovich JE. Geographic distribution of Triatoma dimidiata and transmission dynamics of Trypanosoma cruzi in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:176–183. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumonteil E, Nouvellet P, Rosecrans K, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Gamboa-León R, Cruz-Chan V, Rosado-Vallado M, Gourbière S. Eco-bio-social determinants for house infestation by non-domiciliated Triatoma dimidiata in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumonteil E, Ruiz-Piña H, Rodriguez-Félix E, Barrera-Pérez M, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Rabinovich JE, Menu F. Re-infestation of houses by Triatoma dimidiata after intra-domicile insecticide application in the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:253–256. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762004000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumonteil E, Tripet F, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Payet V, Lanzaro G, Menu F. Assessment of Triatoma dimidiata dispersal in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico using morphometry and microsatellite markers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:930–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falavigna-Guilherme AL, Santana R, Pavanelli GC, Lorosa ES, Araujo SM. Triatomine infestation and vector-borne transmission of Chagas disease in northwest and central Parana, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2004;20:1191–1200. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2004000500012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fe NF, Magalhães LK, Fe FA, Arakian SK, Monteiro WM, Barbosa MD. Occurrences of triatomines in wild and domestic environments in the municipality of Manaus, state of Amazonas. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2009;42:642–646. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822009000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciangeli MD, Carrasco H, Patterson JS, Suarez B, Martinez C, Medina M. Mixed domestic infestation by Rhodnius prolixus Stål, 1859 and Panstrongylus geniculatus Latreille, 1811, vector incrimination and seroprevalence for Trypanosoma cruzi among inhabitants in El Guamito, Lara state, Venezuela. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:501–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciangeli MD, Sanchez-Martin M, Marrero R, Davies C, Dujardin JP. Morphometric evidence for a possible role of Rhodnius prolixus from palm trees in house re-infestation in the state of Barinas (Venezuela) Acta Trop. 2007;101:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferral J, Chavez-Nuñez L, Euan-Garcia M, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Najera-Vasquez MR, Dumonteil E. Comparative field trial of alternative vector control strategies for non-domiciliated Triatoma dimidiata in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:60–66. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick S, Feliciangeli MD, Sanchez-Martin MJ, Monteiro FA, Miles MA. Molecular genetics reveal that silvatic Rhodnius prolixus do colonise rural houses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forattini OP, Ferreira OA, Rabello EX, Barata JMS, Santos JLF. Ecological aspects of South-American trypanosomiasis. 17. The domiciliation development of local Triatominae populations in the Triatoma sordida endemic center. Rev Saude Publica. 1983;17:159–199. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101983000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajate PP, Bottazzi MV, Pietrokovsky SM, Wisnivesky-Colli C. Potential colonization of the peridomicile by Triatoma guasayana (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Santiago del Estero, Argentina. J Med Entomol. 1996;33:635–639. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/33.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa-León R, Ramirez-Gonzalez C, Pacheco-Tucuch F, O’Shea M, Rosecrans K, Pippitt J, Dumonteil E, Buekens P. Chagas disease among mothers and children in rural Mayan communities. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91:348–353. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MN, Aguilar D, Gorchakov R, Rossmann SN, Montgomery SP, Rivera H, Woc-Colburn L, Hotez P, Murray KO. Evidence of autochthonous Chagas disease in southern Texas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:325–330. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourbière S, Dorn P, Tripet F, Dumonteil E. Genetics and evolution of triatomines: from phylogeny to vector control. Heredity. 2012;108:190–202. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2011.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourbière S, Dumonteil E, Rabinovich J, Minkoue R, Menu F. Demographic and dispersal constraints for domestic infestation by non-domiciliated Chagas disease vectors in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourbière S, Gourbière F. Competition between unit-restricted fungi: a metapopulation model. J Theor Biol. 2002;217:351–368. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2002.3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourbière S, Menu F. Adaptive dynamics of dormancy duration variability: evolutionary trade-off and priority effect lead to suboptimal adaptation. Evolution. 2009;63:1879–1892. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva MJ, Palomeque-Rodriguez FS, Costales JA, Davila S, Arcos-Teran L. High household infestation rates by synanthropic vectors of Chagas disease in southern Ecuador. J Med Entomol. 2005;42:68–74. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/42.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva MJ, Suarez-Davalos V, Villacis AG, Ocana-Mayorga S, Dangles O. Ecological factors related to the widespread distribution of sylvatic Rhodnius ecuadoriensis populations in southern Ecuador. 17Parasit Vectors. 2012;5 doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva MJ, Villacis AG. Presence of Rhodnius ecuadoriensis in sylvatic habitats in the southern highlands (Loja province) of Ecuador. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:708–711. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva MJ, Villacis AG, Ocana-Mayorga S, Yumiseva CA, Baus EG. Limitations of selective deltamethrin application for triatomine control in central coastal Ecuador. 20Parasit Vectors. 2011;4 doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtler RE, Cecere MC, Canale DM, Castanera MB, Chuit R, Cohen JE. Monitoring house reinfestation by vectors of Chagas disease: a comparative trial of detection methods during a four-year follow-up. Acta Trop. 1999;72:213–234. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(98)00096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Bracho C, Garcia-Garcia L, Floriani-Verdugo J, Guerrero-Martinez S, Torres-Cosme M, Ramirez-Melgar C, Velasco-Castrejon O. Riesgo de transmisión de Trypanosoma cruzi por transfusión de sangre en México. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1998;4:94–99. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891998000800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Tapia Y, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Dumonteil E. Urban infestation by Triatoma dimidiata in the city of Mérida, Yucatan, Mexico. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:597–606. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Álvarez H, Nakagawa J, Juarez J, Monroy C, Cordón-Rosales C, Gil E. Vector control intervention towards interruption of transmission of Chagas disease by Rhodnius prolixus, main vector in Guatemala. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107:877–887. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762012000700007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Cordón-Rosales C, Trampe R, Kawabata M. Impact of single and multiple residual sprayings of pyrethroid insecticides against Triatoma dimidiata (Reduviiade; Triatominae), the principal vector of Chagas disease in Jutiapa, Guatemala. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herber O, Kroeger A. Pyrethroid-impregnated curtains for Chagas disease control in Venezuela. Acta Trop. 2003;88:33–38. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(03)00193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Aguilar M, Be-Barragán LA, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Tripet F, Dorn P, Dumonteil E. Identification of a large hybrid zone between sympatric sibling species of Triatoma dimidiata in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, and its epidemiological importance. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:1345–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite GR, Santos CB, Falqueto A. Insecta, Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Panstrongylus geniculatus: geographic distribution map. Check List. 2007:147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lent H, Wygodzinsky P. Revision of the Triatominae (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) and their significance as vectors of Chagas disease. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist Nat. 1979;163:123–520. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez G, Moreno J. Genetic variability and differentiation between populations of Rhodnius prolixus and R. pallescens, vectors of Chagas disease in Colombia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1995;90:353–357. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761995000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda MH, Knox MB, Gurgel-Gonçalves R. Occurrence of synanthropic triatomines (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in the Federal District of Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45:71–76. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822012000100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestre-Serrano R, Eyes-Escalante M. Current state of the presence and distribution of triatomine in the department of Atlantico-Colombia: 2003-2010. Bol Mal Salud Amb. 2012;52:125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Melgar S, Chávez JJ, Landaverde P, Herrera F, Rodas A, Enríquez E, Dorn P, Monroy C. The number of families of Triatoma dimidiata in a Guatemalan house. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:221–223. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007005000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menu F, Ginoux M, Rajon E, Lazzari CR, Rabinovich JE. Adaptive developmental delay in Chagas disease vectors: an evolutionary ecology approach. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meszena G, Kisdi E, Dieckmann U, Geritz SAH, Metz JAJ. Evolutionary optimisation models and matrix games in the unified perspective of adaptive dynamics. Selection. 2001;2:193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Monroy C, Castro X, Bustamante DM, Pineda SS, Rodas A, Moguel B, Ayala V, Quiñonez J. An ecosystem approach for the prevention of Chagas disease in rural Guatemala. In: Charron DF, editor. Ecohealth research in practice. Innovative applications of an ecosystem approach to health. Springer; New York: 2012. pp. 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Monroy C, Rodas A, Mejía M, Rosales R, Tabaru Y. Epidemiology of Chagas disease in Guatemala: infection rate of Triatoma dimidiata, Triatoma nitida and Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) with Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma rangeli (Kinetoplastida, Trypanosomatidae) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003a;98:305–310. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroy MC, Bustamante DM, Rodas AG, Enriquez ME, Rosales RG. Habitats, dispersion and invasion of sylvatic Triatoma dimidiata (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) in Peten, Guatemala. J Med Entomol. 2003b;40:800–806. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-40.6.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro FA, Peretolchina T, Lazoski C, Harris K, Dotson EM, Abad-Franch F, Tamayo E, Pennington PM, Monroy C, Cordon-Rosales C, Salazar-Schettino PM, Gomez-Palacio A, Grijalva MJ, Beard CB, Marcet PL. Phylogeographic pattern and extensive mitochondrial DNA divergence disclose a species complex within the Chagas disease vector Triatoma dimidiata. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naiff MF, Naiff RD, Barett TV. Vetores selváticos de doença de Chagas na área urbana de Manaus (AM): atividade de vôo nas estações secas e chuvosas. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1998;31:103–105. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86821998000100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa J, Cordón-Rosales C, Juárez J, Itzep C, Nonami T. Impact of residual spraying on Rhodnius prolixus and Triatoma dimidiata in the department of Zacapa in Guatemala. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003a;98:277–281. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa J, Hashimoto K, Cordón-Rosales C, Juarez JA, Trampe R, Marroquin LM. The impact of vector control on Triatoma dimidiata in the Guatemalan department of Jutiapa. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003b;97:288–297. doi: 10.1179/000349803235001895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa J, Juarez J, Nakatsuji K, Akiyama T, Hernandez G, Macal R, Flores C, Ortiz M, Marroquin L, Bamba T, Wakai S. Geographical characterization of the triatomine infestations in north-central Guatemala. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2005;99:307–315. doi: 10.1179/136485905X29684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noireau F, Bosseno MF, Carrasco R, Telleria J, Vargas F, Camacho C, Yaksic N, Brenière SF. Sylvatic triatomines (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) in Bolivia - trends toward domesticity and possible infection with Trypanosoma cruzi (Kinetoplastida, Trypanosomatidae) J Med Entomol. 1995;32:594–598. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/32.5.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noireau F, Brenière F, Ordoñez J, Cardozo L, Morochi W, Gutierrez T, Bosseno MF, Garcia S, Vargas F, Yaksic N, Dujardin JP, Peredo C, Wisnivesky-Colli C. Low probability of transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi to humans by domiciliary Triatoma sordida in Bolivia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997a;91:653–656. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90508-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noireau F, Cortez MGR, Monteiro FA, Jansen AM, Torrico F. Can wild Triatoma infestans foci in Bolivia jeopardize Chagas disease control efforts? Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noireau F, Dujardin JP. Biology of Triatominae. In: Telleria J, Tibayrenc M, editors. American trypanosomiasis: Chagas disease one hundred years of research. Elsevier; Burlington: 2010. 870 [Google Scholar]

- Noireau F, Flores R, Gutierrez T, Dujardin JP. Detection of sylvatic dark morphs of Triatoma infestans in the Bolivian Chaco. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997b;92:583–584. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761997000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noireau F, Gutierrez T, Flores R, Brenière F, Bosseno MF, Wisnivesky-Colli C. Ecogenetics of Triatoma sordida and Triatoma guasayana (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in the Bolivian Chaco. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999a;94:451–457. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761999000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noireau F, Zegarra M, Ordoñez J, Gutierrez T, Dujardin JP. Genetic structure of Triatoma sordida (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) domestic populations from Bolivia: application on control interventions. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999b;94:347–351. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761999000300011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouvellet P, Cucunubá ZM, Gourbière S. Ecology, evolution and control of Chagas disease: a century of neglected modelling and a promising future. Adv Parasitol. 2015;87:135–191. doi: 10.1016/bs.apar.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouvellet P, Dumonteil E, Gourbière S. The improbable transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi to human: the missing link in the dynamics and control of Chagas disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco-Tucuch FS, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Gourbière S, Dumonteil E. Public street lights increase house infestation by the Chagas disease vector Triatoma dimidiata. PLoS ONE. 2012;7: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzera F, Dujardin JP, Nicolini P, Caraccio MN, Rose V, Tellez T, Bermudez H, Bargues MD, Mas-Coma S, O’Connor JE, Perez R. Genomic changes of Chagas disease vector, South America. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:438–446. doi: 10.3201/eid1003.020812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payet V, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Rabinovich J, Menu F, Dumonteil E. Variations in sex-ratio, feeding and fecundity of Triatoma dimidiata between habitats in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9:243–251. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2008.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]