Abstract

Purpose

Some muscle injuries are the result of a single lengthening contraction. Our goal was to evaluate the contributions of angular velocity, arc of motion, and timing of contractile activation relative to the onset of joint motion in an animal model of muscle injury using a single lengthening contraction.

Methods

The intact tibialis anterior (TA) muscle of rats was activated while lengthened, preceded by a maximal isometric contraction of 0, 25, 50, 100, or 200 ms. The lengthening contraction was performed at two different angular velocities (300 or 900°/s) and through two different arcs of motion (90° or 45°).

Results

Muscle contractile function, as measured by maximal isometric tetanic tension, was significantly decreased only when the TA was activated at least 50 ms prior to the motion, regardless of angular velocity or arc of motion.

Conclusion

The data indicated that the duration of an isometric contraction prior to a single lengthening contraction determined the extent of muscle injury irrespective of two different angular velocities.

Keywords: Skeletal muscle, Sports medicine, Lengthening contraction, Rehabilitation, Biomechanics, Trauma, Injury, Muscle, Prevention, Motor neuron recruitment

1. Introduction

Mechanical stabilization is largely imparted by the muscles associated with a joint and can be impaired by muscle strains that occur from sports-related injuries (Garrett, 1996; Best, 1997) or from motor vehicle accidents, such as a whiplash injury (Kettler et al., 2002; Brault et al., 2000). Common to all these muscle trauma is that a single, lengthening contraction is the cause for the post-injury loss of muscle force. Characterizing the biomechanical conditions for a single, lengthening contraction-induced injury provides experimental data that can be used in mathematical models and may help to develop better approaches to prevent lengthening contraction-induced muscle injuries.

Several models of lengthening contraction-induced injury have been used, however, different models and experimental designs make it difficult to apply some of the findings directly to acute muscle injuries. Using repetitive lengthening contractions tension (Warren et al., 1993; Brooks et al., 1995; Hunter and Faulkner, 1997), strain (Lieber and Friden, 1993; Brooks et al., 1995; Talbot and Morgan, 1998), and initial muscle length (Hunter and Faulkner, 1997) have been correlated with the loss of force, but velocity of contraction has not (Hunter and Faulkner, 1997; Willems and Stauber, 2002). Despite these efforts, the contribution of certain biomechanical variables to a single strain injury is still unclear and the role of pre-activation has not been rigorously tested.

The purpose of this study was to assess how changes in angular velocity, arc of motion, and timing of contractile activation would affect the extent of muscle injury (which we defined as a post-contraction loss of isometric force) during a single lengthening contraction. Based on the literature, we expected a greater degree of injury with a larger arc of motion, but not with increased angular velocity. We further hypothesized that the amount of tension developed at the onset of the single lengthening contraction would result in a muscle injury so that higher initial tension would subsequently lead to larger loss of contractile function. We therefore manipulated the duration of contractile activation at the onset of a single lengthening contraction (pre-activation), measured the torque at the onset of the lengthening contraction (T1) and evaluated its role in muscle injury. An understanding of this relationship may provide insight into acute muscle strains in fast and explosive sports activities (Garrett, 1996; Best, 1997) as well as the reduction of muscle injuries after certain motor vehicle accidents (Brault et al., 2000; Tencer et al., 2002).

2. Methods

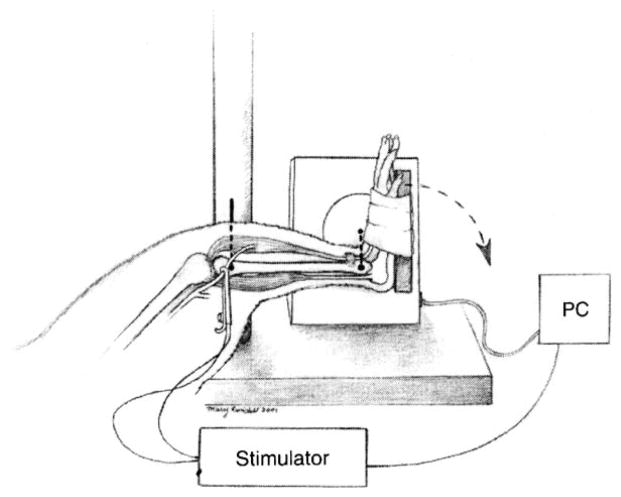

The lengthening contraction-induced injury model that we used was approved by the University of Maryland School of Medicine IACUC and based on the work from other investigators (Best et al., 1995). Male Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 50), Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), weighing 386±42 g, were anesthetized with intraperitoneal ketamine/xylazine (40/10mg/kg body mass, respectively). With the animal supine (Fig. 1), the hindlimb was stabilized using a transosseous 16-gauge needle through the proximal tibia and the foot was secured onto a plate. The axis of the footplate was attached to a stepper motor (model T8904, NMB Technologies, Chatsworth, CA), a potentiometer (to measure angular position), and a torque sensor (model QWFK-8M, Sensotec, Columbus, OH). To collect the data we used a custom program, which was developed from commercial software (Labview version 4.1, National Instruments, Austin, TX) and we used it to synchronize contractile activation, onset of ankle rotation, and torque data collection. Signals (torque and position) were obtained at a rate of 1000 Hz and amplified (model DV-05, Sensotec, Columbus, OH) before being sampled by the computer via 12-bit analog to digital board (LabPC-1200, National Instruments, Austin, TX). The torque sensor was calibrated in situ by using weights and a known moment arm, which allowed us to determine its linearity up to a maximum of 140 N mm. By moving the stepper motor under unloaded conditions we determined that its sensitivity at 900°/s was 1.4 N mm/ms. To induce the lengthening contraction of the dorsiflexors, the peroneal nerve was dissected free through a small incision and clamped with a subminiature electrode (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA), which was used to stimulate the muscles with a supra-maximal tetanic contraction. An isolation unit (model PSIU6, Grass Instruments, Warwick, RI) was used between the stimulator and electrode to minimize artifact. Prior to the lengthening contraction (1 min), we performed a tetanic stimulation to assess the possibility for achieving full contractile activation and also performed an unstimulated (passive) torque test. The maximal active torque was obtained by subtracting the passive torque from the total torque at each data collection point (1 ms).

Fig. 1.

Muscle Injury Model: the tibia of the hindlimb was stabilized and the foot secured to a plate driven by a stepper motor. The peroneal nerve was used to stimulate the TA anterior (a dorsiflexor) at a selected time while the plate forced the foot into plantar flexion at a selected velocity.

To quantify the extent of injury we determined the maximal tetanic strength after the single lengthening contraction. All contractile data were obtained within minutes after the single lengthening contraction. The distal tendon of the tibialis anterior (TA) was released and its proximal portion was secured in a custom-made metal clamp and attached to a load cell (model FT03, Grass instruments, RI) using a suture tie (4.0 coated Vicryl). The load cell was mounted to a micromanipulator (Kite Manipulator, World Precision Instruments Inc, Sarasota, FL) so that the TA could be adjusted to resting length and aligned. The tibia was stabilized with a 16-gauge needle and the peroneal nerve was used to stimulate the TA. The TA was protected from cooling by a heat lamp and from dehydration by mineral oil. The signals from the load cell (calibrated before each test) were fed via a DC amplifier (model P122, Grass Instruments, Warwick, RI) to an A/D board to be collected and stored by acquisition software (PolyVIEW version 2.1, Grass Instruments, Warwick, RI). In a series of preliminary experiments, we attached the TA to the load cell and applied single twitches (rectangular pulse of 1 ms) at different muscle lengths in order to determine the optimal length (resting length, L0). At this length we gradually increased the stimulation intensity and frequency to establish a force-frequency relationship. A maximally fused tetanic contraction was obtained at 75 Hz (300 ms train duration with 1 ms pulses at a constant current of 5 mA). We used 150% of the maximum stimulation intensity to activate the TA in our experiments in order to induce maximal contractile activation (P0). Maximal tetanic tension was measured after 5 min of continuous stimulation at 1 Hz and expressed as percentage of P0, providing an index of fatigue. Muscle resting length, measured using calipers, was defined as the distance between the tibial tuberosity and the myotendinous junction. All instrumentation was turned on at least 30 min prior to testing to be calibrated and to minimize thermal drift of the transducers.

We assessed whether our injury model was consistent with physiological conditions. Therefore, we determined the sarcomere length at different joint angles and verified these measurements with the torque–angle curve, since we could not measure muscle length directly. In separate animals, we determined the sarcomere length of the muscle fibers in the TA at 0° and 90° of plantar flexion. This was performed to verify where the TA was operating on the length–tension curve. We secured the hindlimb of non-injured animals (n = 8) with the ankle at neutral (0° of plantarflexion) using an L-bracket or at 90° of plantarflexion using a plate before the animals were fixed by perfusion. Subsequently, the limb was disarticulated, skinned, and placed in fixative for another 48 h. The TA muscle was dissected free and placed in 30% nitric acid solution for 48 h to macerate the connective tissue. The muscle was then rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and placed in 50% glycerol/PBS solution for microdissection. A total of 50 single fibers were randomly selected and teased out, mounted on glass coverslips in 50% glycerol/PBS, and photographed with phase-contrast optics at 40×. Images of the fibers were analyzed with NIH Image software (version 1.61: National Institutes of Health) using Fourier transforms of the images to determine periodicity, which corresponded to the sarcomere lengths of the fibers. The sarcomere length with the TA in a neutral ankle position (0°) averaged 2.07±0.11 μm and at 90° of plantar flexion it was 2.56±0.03 μm. We also measured the moment arm (distance from the lateral malleolus to the extensor retinaculum) of the TA at neutral position (0°) and it averaged 4.23±0.88 mm. Since the supramaximal stimulation affected two dorsiflexors the TA and the extensor digitorum longus (EDL), we performed the following measurements. We ascertained the maximal torque and its associated angle for both the TA and the EDL independently, by using synergist ablation and determined the individual contributions of the EDL and the TA during ankle motion. By severing the EDL, we determined a torque–angle relationship of the TA and found that it had a maximal isometric tetanic torque of 23 N mm at 23° of plantar flexion. By severing the TA, we determined that the EDL had a maximal isometric tetanic torque of 10 N mm at 68° of plantar flexion. The maximal tetanic torque–angle relationship combined with the sarcomere length measurements indicated that in our model using an arc of motion from neutral to 90° of plantar flexion the lengthening contraction of the TA occurred on the plateau and the top of the descending limb of the length-tension curve.

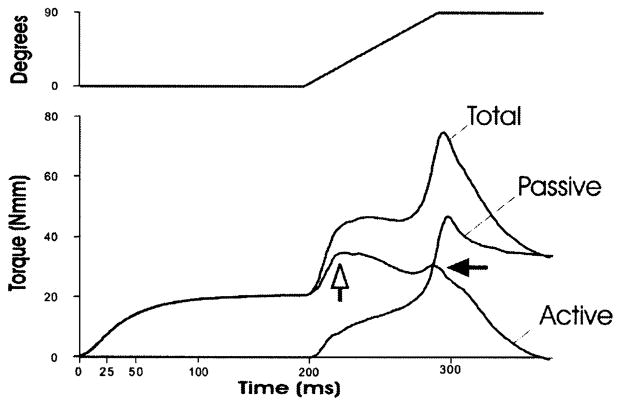

Since the torque that we measured in real time represents the contributions of both active and passive torque we subtracted the passive torque (torque develop during the plantar flexion of the ankle with the TA not activated) from the total torque in order to obtain active torque. A representative experiment (a 90° arc of motion at 900°/s) is shown in Fig. 2. The passive torque increased sharply in the first 10–20 ms, then rose linearly throughout the range only to increase exponentially in the last 25 ms, which corresponded to the force of the stretched dorsiflexors and ankle ligaments in the last 20° of plantar flexion. Active torque rose sharply and reached a point where it plateaued and then slowly decreased, suggesting that mechanical damage may have occurred, similar to a yield point in biomechanical experiments (open arrow, Fig. 2). A slower angular velocity of 300°/s over a 90° arc revealed a similar pattern. At both angular velocities we observed a second, smaller peak (closed arrow, Fig. 2) only when we used a 90° arc and not a 45° arc. This second peak may represent the contractile activation of the agonistic EDL, since it occurred near the end of the arc of motion.

Fig. 2.

Real time torque measurements during the lengthening contraction. The torque shown is the average at each data point (1 ms intervals) from five different animals. The muscle injury was created with an isometric contraction of 200 ms prior to a lengthening contraction at 900°/s over a 90° arc. An initial rise in total torque is followed by a plateau phase only to rise sharply near the end of the motion. Passive torque was obtained by moving the ankle through the 90° arc without stimulation. The maximal active torque was obtained by subtracting the passive torque from the total torque at each data collection point (1 ms). After a sharp rise in active torque (contributed nearly exclusively by the TA), a yield point is observed (open arrow) and a smaller second peak could represent the contribution of the EDL (closed arrow) during the lengthening contraction of the dorsiflexors.

The rats were randomly placed into one of nine experimental groups or sham-injured group (n = 5 for each group, an additional group of non-injured TA was used as a reference). In a first series of experiments, the TA was activated 200 ms prior to the onset of plantar flexion and continued throughout the lengthening contraction. In order to determine whether arc of motion and/or angular velocity had an effect in this injury model, the lengthening contraction was performed at: an angular velocity of 300°/s with an arc of 45° or 90° and an angular velocity of 900°/s with an arc of 45° or 90°. In a subsequent series of experiments, we activated the TA for a different duration prior to the onset of plantar flexion (pre-activation) and its contractile activation continued throughout the lengthening of the muscle at an angular velocity of 900°/s from 0° to 90° of plantar flexion. We tested pre-activation durations of 0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 ms. Control TAs were from operated legs, however each TA was sham-stimulated and a was passively moved through the arc of motion without nerve stimulation (sham-injured).

Contractile data from each experiment were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA, Sigma-Stat, San Rafael, CA). When a significant F-ratio was found, a Tukey post hoc analysis was performed to determine where significant differences had occurred. To rule out an interaction effect, a two-way ANOVA was also performed using on set of activation and angular velocity as the grouping variables. In addition, a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was calculated to determine if there was a significant correlation between dependent and independent variables. Significance was set at p<0.05 and all results are reported as means±SD.

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes our findings with two different angular velocities and arcs of motion. Compared to controls each of the different lengthening contraction conditions (all with a 200 ms isometric pre-activation) led to a 30–60% drop in twitch and tetanic tension. A variable such as fatigue was not affected but resting length increased significantly (from 26.12±1.03mm in sham-injured TA to 27.58±0.89 mm) only when we used a 45° arc and not with a 90° arc.

Table 1.

Summary of functional characteristics of injured tibialis anterior muscles as compared to controls (sham-injured)

| Angular velocity | 0 | 900°/s | 300°/s | 900°/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing of contractile activation | Sham-injured | 200 ms prior | 200 ms prior | 200 ms prior |

| Arc | 0 | 90° | 90° | 45° |

| Twitch tension (t) (N) | 2.45±0.80 | 1.17±0.30a | 0.95±0.31a | 0.96±0.29a |

| Tetanic tension (T) (N) | 8.24±1.88 | 4.36±1.16a | 5.05±0.86a | 5.84±1.07a |

| Fatigue index | 16±14.11 | 27±9.53 | 24±11.6 | 14±5.98 |

| Resting length (mm) | 26.12±1.03 | 24.40±0.96 | 25.83±1.93 | 27.58±0.89a |

Results are given as mean±SD. Fatigue index: maximal tetanic tension after 5 min stimulation at 1-Hz and is reported as % of maximal tetanic tension (P0) before injury.

Indicates statistically significance from sham-injured (p<0.05) and n = 5.

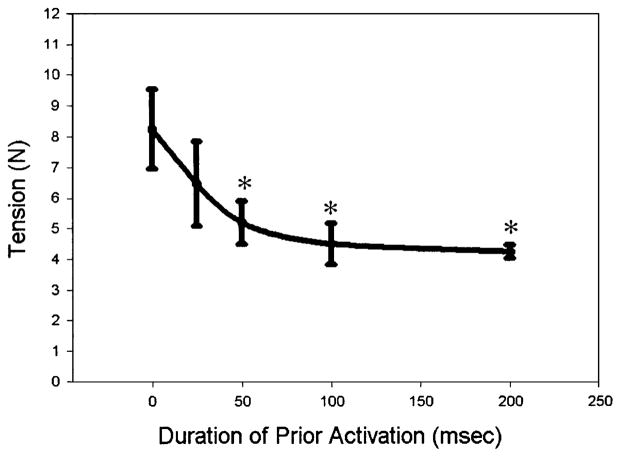

To determine the contributions of pre-activation time, we altered the duration of contractile activation prior to the onset of motion and evaluated its effect on injury (post-lengthening contraction maximal tetanic tension, Fig. 3). A single lengthening contraction without pre-activation did not lead to a subsequent injury (8.21±1.88 N, n = 5) compared to sham-injured controls (8.24±1.34 N, n = 5) and no difference was detected with a pre-activation of 25 ms (6.50±1.37 N, n = 5). Pre-activation of 50, 100, or 200 ms resulted in a significant loss of force (P<0.001) to 5.20±0.70, 4.49±0.67, and 4.23±0.22 N, respectively (Fig. 3). A plot of post-lengthening force versus pre-activation time approached an asymptote (Fig. 3), suggesting that stimulating the muscle longer than 100 ms prior to a lengthening contraction will not cause much additional injury.

Fig. 3.

Maximal tetanic isometric tension after a single lengthening contraction with different pre-activation times. A significant loss of force occurred only when the TA was activated 50 ms or longer prior to (and throughout) the lengthening contraction (mean ±SD, n = 5 per group, *p<0.05).

We also evaluated the torque at the onset of the lengthening contraction with different pre-activation durations (T1, torque 1 ms into the lengthening contraction, Table 2). Without the pre-activation, T1 was 3.25±2.42 Nmm (n = 5) and gradually increased with the duration of pre-activation until it reached a significant difference when pre-activation lasted at least 50 ms (T1=17.8±0.73 Nmm). We found a strong correlation (r = 0.84) between T1 and the duration of pre-activation, which indicated that by manipulating the duration of pre-activation we could control the tensile forces at the onset of the lengthening contraction.

Table 2.

Torque (T) measurements during a single lengthening contraction with different pre-activation time

| Timing of contractile activation (pre-activation, ms) | Torque (T1, Nmm) at start of motion. | Peak T (Nmm) at the end of motion |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3.25±2.42 | 55.03±5.13 |

| 25 | 7.13±8.83 | 54.60±1.61 |

| 50 | 17.80±0.34a | 59.25±7.95 |

| 100 | 22.46±0.46a | 66.21±4.25a |

| 200 | 22.87±2.61a | 77.58±6.63a |

Results are given as mean±SD.

Indicates statistically significance from sham-injured (p<0.05) and n=5

Combined, the data indicate that the mechanical conditions at the onset of the lengthening contraction determine the degree of subsequent force loss and can be manipulated by pre-activation. This was indicated by a strong negative correlation (r = –0.95) between duration of pre-activation (Table 2) and post-lengthening contraction force loss (Fig. 3). Total peak torque (also Table 2), which predominantly represents the peak passive torque near the end of the arc, also varied with the different durations of pre-activation, but was only moderately correlated with the post-contraction force deficit and not significant (r = –0.55, p = 0.09). These experiments indicate an isometric contraction lasting at least 50 ms prior to a single lengthening contraction is required for loss of contractile function. In an effort to estimate stiffness we analyzed the change in active torque over the change in angular motion. Using linear regression analysis on data from the initial 20 ms we could not establish any significant changes with varying pre-activation times.

4. Discussion

The data show that varying the timing of contractile activation before a single lengthening contraction (pre-activation) determined the amount of injury, measured by the loss in post-lengthening contraction force. The TA muscle was injured after a single lengthening contraction only when the muscle was fully isometrically activated at least 50 ms prior to the onset of lengthening and when the muscle length was operating in the plateau and beginning of the descending limb of the length–tension curve. Angular velocity during the lengthening contraction did not affect the degree of functional muscle injury. The data indicate that the duration of an isometric contraction (pre-activation) prior to a lengthening contraction created the necessary mechanical conditions for muscle injury, especially when the muscle and its muscle fibers were at a length where they develop a significant amount of force.

We measured torque and angular motion rather than force and strain, which have been assessed either in situ (Ashton-Miller et al., 1992; Lieber et al., 1994; Best et al., 1999; Brooks et al., 1995) or in isolated preparations (Warren et al., 1993). Despite the advantage of obtaining very accurate mechanical data, clinicians may find it difficult to directly apply these findings to scenarios of acute muscle injury and rehabilitation strategies. Therefore while the torque and angular motion may limit the interpretation of our study, the angular velocities that we used are based on physiologically relevant observations (Shealy et al., 1992; Ingen Schenau et al., 1985; de Leon et al., 1994). In addition, we compared our (angular) variables with the linear variables reported by others (Ashton-Miller et al., 1992; Lieber et al., 1994; Best et al., 1999; Warren et al., 1993; Brooks et al., 1995; Hunter and Faulkner, 1997; Lieber and Friden, 1993; Talbot and Morgan, 1998). Considering that the moment arm of the TA at 0° was 4.23±0.88 mm, which is an oversimplification (Lieber, 1993), an angular velocity of 900°/s represented a linear velocity of 65 mm/s (v = rω). Considering that the TA resting length (Lo) was 26.12±1.03 mm, the linear velocity in our conditions (at 900°/s) equals 2.5 Lo/s. Using our sarcomere length measurements, a 90° angular displacement represents a strain approximating 24% ([2.56–2.07 μm]/2.07 μm×100). The physiological relevance of choosing a 90° arc of motion is obtained from kinesiological data, which showed that the TA of the rat is active during an arc of at least 120° of dorsiflexion during running( de Leon et al., 1994). These calculations facilitate the comparison between our model and other models in the literature.

In our experiments, we activated all the antecrural muscles, which may confound the interpretation of our results, since it is possible that our model had a higher degree of compliance and that some of the strain was dissipated by the connective tissue associated with the EDL and the TA (Huijingand Baan, 2001). Despite our efforts to use physiological relevant variables by establishing the sarcomere length, research suggests that there is a large range in functional sarcomere lengths (Burkholder and Lieber, 2001) and to make matter even more complex sarcomeres can have different optimal lengths for twitch tension and tetanic tension (Zuurbier et al., 1995).

Nearly all models of lengthening contraction-induced muscle injury, using either repetitive contractions (Lieber and Friden, 1993; Talbot and Morgan, 1998; Warren et al., 1993), a single lengthening contraction (Brooks et al., 1995; Hunter and Faulkner, 1997) either in situ (Brooks et al., 1995; Hunter and Faulkner, 1997) or isolated preparations (Warren et al., 1993) use pre-activation to some extent. Pre-activation does not seem to be a pre-requisite to induce muscle injury after repetitive lengthening contractions (Lieber and Friden, 1993; Warren et al., 2002) our data however indicate that when using a single lengthening contraction pre-activation is a key contributor to muscle injury. Our data are in line with results from others, in which loss of force is a function of strain (Lieber and Friden, 1993; Brooks et al., 1995; Talbot and Morgan, 1998) and initial muscle length (Hunter and Faulkner, 1997) but not dependent on the velocity of contraction (Hunter and Faulkner, 1997; Willems and Stauber, 2002). Besides the clinical relevance, a single contraction-based injury also eliminates refractory effects either from mechanical (Herzog and Leonard, 2002) or metabolic origin (Fitts, 1994). Our data indicate that when muscle undergoes a single lengthening contraction on the plateau or at the beginning of the descending limb of the length–tension curve (where high forces are generated) it is at risk to be injured.

One possible mechanism that can explain the association between high forces at the onset of a lengthening contraction and loss of contractile function is that the isometric pre-activation leads to increased stiffness in the muscle. Stiffness in the muscle is a result of both dynamic changes caused by the extent of actin/myosin interactions (mechanical activation) (Ford et al., 1981; Ettema and Huijing, 1994; Benz et al., 1998) and static changes in the series-elastic elements (Bagni et al., 2002; Minajeva et al., 2002). Despite the difficulty to measure muscle stiffness directly during a contraction (Benz et al., 1998) it is reasonable to assume that by manipulating contractile activation, we manipulated stiffness indirectly. The requirement for a pre-activation of >50 ms can be explained by the principle of an electromechanical delay.

Previous studies have determined that mechanical activation in a fast muscle such as the rat TA takes about 30–35 ms (Rosenblueth and Rubio, 1959) and that this activation represents a series of events such as membrane depolarization, excitation/contraction coupling, and actin/myosin interaction. The causal relation between a pre-activation duration of at least 50 ms and muscle injury is quite plausible considering the electromechanical delay within the muscle fiber and the latency caused by the compliance of the perimuscular connective tissue within the muscle. To make this interpretation clinically relevant and we can apply these observations in the example of a whiplash-like injury, in which neck muscles are activated 65–75 ms after the onset of cervical motion (Siegmund et al., 2003). Thus methods that can manipulate the onset of contractile activation allowing less then 50 ms pre-activation time prior to an anticipated active lengthening may affect the degree of muscle injury. Some practical applications of these findings may include the design of passive restraint safety devices (e.g. automobile seat belts). In another example, rehabilitation strategies that involve plyometric exercises may minimize contraction-induced injury by allowing sufficient time for relaxation between repetitions.

Acknowledgments

The research as made possible through a grant from the NIH (K01-HD01165) and a grant from the National Football League Charities to PGDD and the muscle-biology training program (T-32 AR07592-06) RL. We would like to thank Dr. David Pumplin for his help with the sarcomere length measurements.

References

- Ashton-Miller JA, He Y, Kadhiresan VA, McCubbrey DA, Faulkner JA. An apparatus to measure in vivo biomechanical behavior of dorsi- and plantarflexors of mouse ankle. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1992;72:1205–1211. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.3.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagni MA, Cecchi G, Colombini B, Colomo F. A noncross-bridge stiffness in activated frog muscle fibers. Biophysical Journal. 2002;82:3118–3127. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75653-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benz RJ, Friden J, Lieber RL. Simultaneous stiffness and force measurements reveal subtle injury to rabbit soleus muscles. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1998;179:147–158. doi: 10.1023/a:1006824324509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best TM. Soft-tissue injuries and muscle tears. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 1997;16:419–434. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best TM, McElhaney JH, Garrett WE, Jr, Myers BS. Axial strain measurements in skeletal muscle at various strain rates. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 1995;117:262–265. doi: 10.1115/1.2794179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best TM, Fiebig R, Corr DT, Brickson S, Ji L. Free radical activity, antioxidant enzyme, and glutathione changes with muscle stretch injury in rabbits. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1999;87:74–82. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault JR, Siegmund GP, Wheeler JB. Cervical muscle response during whiplash: evidence of a lengthening muscle contraction. Clinical Biomechanics. 2000;15:426–435. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(99)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SV, Zerba E, Faulkner JA. Injury to muscle fibres after single stretches of passive and maximally stimulated muscles in mice. Journal of Physiology. 1995;488:459–469. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder TJ, Lieber RL. Sarcomere length operating range of vertebrate muscles during movement. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2001;204:1529–1536. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.9.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettema GJ, Huijing PA. Skeletal muscle stiffness in static and dynamic contractions. Journal of Biomechanics. 1994;27:1361–1368. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitts RH. Cellular mechanisms of muscle fatigue. Physiological Reviews. 1994;74:49–94. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford LE, Huxley AF, Simmons RM. The relation between stiffness and filament overlap in stimulated frog muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1981;311:219–249. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett WE., Jr Muscle strain injuries. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1996;24:S2–S8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog W, Leonard TR. Force enhancement following stretching of skeletal muscle: a new mechanism. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2002;205:1275–1283. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.9.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijing PA, Baan GC. Myofascial force transmission causes interaction between adjacent muscles and connective tissue: effects of blunt dissection and compartmental fasciotomy on length force characteristics of rat extensor digitorum longus muscle. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry. 2001;109:97–109. doi: 10.1076/apab.109.2.97.4269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter KD, Faulkner JA. Pliometric contraction-induced injury of mouse skeletal muscle: effect of initial length. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1997;82:278–283. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.1.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingen Schenau GJ, Bobbert MF, Huijing PA, Woittiez RD. The instantaneous torque-angular velocity relation in plantar flexion during jumping. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1985;17:422–426. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198508000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettler A, Hartwig E, Schultheiss M, Claes L, Wilke HJ. Mechanically simulated muscle forces strongly stabilize intact and injured upper cervical spine specimens. Journal of Biomechanics. 2002;35:339–346. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon R, Hodgson JA, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Extensor- and flexor-like modulation within motor pools of the rat hindlimb during treadmill locomotion and swimming. Brain Research. 1994;654:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber RL. Skeletal muscle architecture: implications for muscle function and surgical tendon transfer. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1993;6:105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber RL, Friden J. Muscle damage is not a function of muscle force but active muscle strain. Jounal of Applied Physiology. 1993;74:520–526. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.2.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber RL, Schmitz MC, Mishra DK, Friden J. Contractile and cellular remodeling in rabbit skeletal muscle after cyclic eccentric contractions. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1994;77:1926–1934. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.4.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minajeva A, Neagoe C, Kulke M, Linke WA. Titin-based contribution to shortening velocity of rabbit skeletal myofibrils. Journal of Physiology. 2002;540:177–188. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblueth A, Rubio R. The time course of the isometric and istonic twitches of striated muscles. Archives Internationales de Physiologie et de Biochimie. 1959;67:718–731. doi: 10.3109/13813455909067184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shealy MJ, Callister R, Dudley GA, Fleck SJ, Dudley GA., Investigator Human torque velocity adaptations to sprint, endurance, or combined modes of training. American Journal Sports Medicine. 1992;20:581–586. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund GP, Sanderson DJ, Myers BS, Inglis JT. Rapid neck muscle adaptation alters the head kinematics of aware and unaware subjects undergoing multiple whiplash-like perturbations. Journal of Biomechanics. 2003;36:473–482. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00458-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot JA, Morgan DL. The effects of stretch parameters on eccentric exercise-induced damage to toad skeletal muscle. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1998;19:237–245. doi: 10.1023/a:1005325032106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tencer AF, Kaufman R, Ryan K, Grossman DC, Henley BM, Mann F, Mock C, Rivara F, Wang S, Augenstein J, Hoyt D, Eastman B. Crash injury research and engineering network (CIREN) femur fractures in relatively low speed frontal crashes: the possible role of muscle forces. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2002;34:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(00)00097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren GL, Hayes DA, Lowe DA, Armstrong RB. Mechanical factors in the initiation of eccentric contraction-induced injury in rat soleus muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1993;464:457–475. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren GL, Ingalls CP, Armstrong RB. Temperature dependency of force loss and Ca(2+) homeostasis in mouse EDL muscle after eccentric contractions. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative and Comparitive Physiology. 2002;282:R1122–R1132. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00671.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems ME, Stauber WT. Force deficits by stretches of activated muscles with constant or increasing velocity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2002;34:667–672. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200204000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuurbier CJ, Heslinga JW, Lee-de Groot MB, van der aarse WJ. Mean sarcomere length-force relationship of rat muscle fibre bundles. Journal of Biomechanics. 1995;28:83–87. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]