Abstract

Being born small due to poor growth before birth increases the risk of developing metabolic disease, including type 2 diabetes, in later life. Inadequate insulin secretion and decreasing insulin sensitivity contribute to this increased diabetes risk. Impaired placental growth, development and function are major causes of impaired fetal growth and development and therefore of IUGR. Restricted placental growth (PR) and function in non-human animals induces similar changes in insulin secretion and sensitivity as in human IUGR, making these valuable tools to investigate the underlying mechanisms and to test interventions to prevent or ameliorate the risk of disease after IUGR. Epigenetic changes induced by an adverse fetal environment are strongly implicated as causes of later impaired insulin action. These have been well-characterised in the PR rat, where impaired insulin secretion is linked to epigenetic changes at the Pdx-1 promotor and reduced expression of this transcription factor. Present research is particularly focussed on developing intervention strategies to prevent or reverse epigenetic changes, and normalise gene expression and insulin action after PR, in order to translate this to treatments to improve outcomes in human IUGR.

Keywords: IUGR, Placental restriction, Diabetes, Epigenetics, Interventions

1. Introduction

Poor growth before birth is consistently associated with increased risks of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) in humans, and the underlying changes in insulin sensitivity and secretion that lead toT2D following IUGR are becoming better understood. Impaired placental growth, development and function are major causes of impaired fetal growth and development and therefore of IUGR, where the growth of the fetus is restricted relative to its genetic potential. Animal studies have allowed the role of the placenta in later development of disease of progeny to be directly investigated, and here we discuss current knowledge of mechanisms and consequences of placental restriction in the sheep and rat for insulin action after birth. Development of these animal models also allows development and testing of interventions to prevent impaired insulin action after IUGR, and we conclude with a discussion of the current research in this area.

2. IUGR and diabetes in humans

In humans, size at birth, measured as birth weight in the majority of studies, is consistently and inversely related to glucose intolerance and the prevalence of T2D [1–3]. These inverse relationships are usually either linear, or J-shaped, depending on the age and ethnicity of the population being studied, where high birth weight babies of pregnancies affected by gestational diabetes are also at increased risk of T2D in later life. Although earlier studies often did not separate effects of gestational age from intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) as determinants of birth weight, a more recent study has confirmed that low birth weight predicts increased risk of T2D independent of gestational age [4]. The majority of human studies are limited in the extent of fetal growth measures that are collected, and most therefore define IUGR in terms of low birth weight relative to a local reference population, usually corrected for gestational age, rather than by direct measures of slowing growth. IUGR and small for gestational age (SGA) are therefore often used interchangeably in human literature. Nevertheless, a low birth weight (SGA) may reflect genetic determinants of fetal growth in the absence of growth restriction, and a baby may be growth-restricted and within the normal birth weight range.

Not only is low birth weight consistently related to increased risk of T2D, but this accounts for a substantial proportion of lifetime risk. In a population of men aged 80 in Sweden, the prevalence of T2D decreased by 53% for every 1 kg increase in birth weight, whilst a birth weight of less than 3 kg increased the risk of T2D by 18% overall [5]. Meta-analysis of data from 30 studies, of >150,000 individuals in young and old adulthood, reported an odds ratio for T2D of 0.80 (0.72–0.89) for a 1 kg increase in birth weight [3]. Contemporary cohorts of low birth weight babies and children may be at even greater risk of developing later T2D, since low birth weight also increases the risk of developing obesity in an environment of high food availability [6], and obesity impairs insulin sensitivity and significantly increases the risk for developing T2D [7].

3. Human IUGR and determinants of insulin action

The two determinants of insulin action, and thus risk of impaired glucose tolerance and T2D, are insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion. Insulin action, also referred to as insulin disposition, can be calculated by multiplying insulin sensitivity and insulin availability at target tissues [8]. Small size at birth in humans is consistently associated with impaired insulin sensitivity in adolescents and adults, including indirect calculations of insulin sensitivity as well as studies in which insulin sensitivity has been independently and directly measured by hyperinsulinaemic euglycaemic clamp, considered the “gold-standard” method [1]. For example, Jacquet et al. [9] reported approximately 20% lower insulin sensitivity in young adult men who had weight or height at birth below the 3rd centile, compared to controls. Intriguingly, one study in humans has suggested that insulin sensitivity in neonates is positively related to size at birth [10]. Early enhanced insulin action in the IUGR neonate due to increased insulin abundance and/or sensitivity may contribute to catch-up growth, followed by impaired insulin sensitivity which may emerge as early as 1 year of age [11–13].

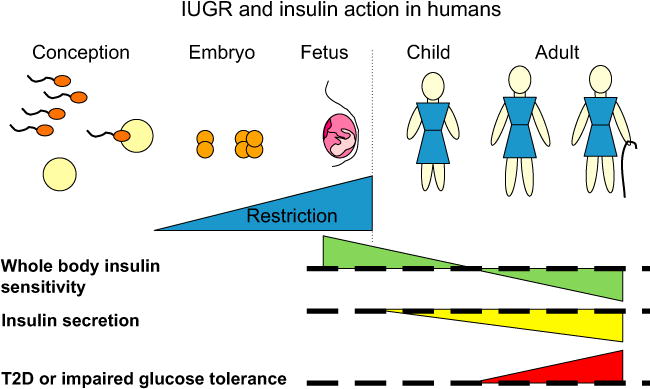

In contrast to the relationships between birth weight and insulin sensitivity, those between birth size and insulin secretion are relatively variable in humans. In the meta-analysis mentioned above, size at birth was negatively related to measures of insulin secretion in 16 of 24 studies, not related in six of 24 studies, and positively related in seven of 24 studies (some studies reported different relationships for population subgroups) [1]. This variability possibly reflects differential changes in factors affecting insulin secretion; changes in demand due to decreasing insulin sensitivity, and changes in insulin secretion capacity. Thus low circulating insulin may reflect low demand for insulin in a highly insulin-sensitive individual, or failure of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion due to β-cell dysfunction. This means that accurate assessment of insulin secretion needs to consider insulin secretion relative to insulin sensitivity, i.e. whether insulin secretion is appropriate for demand [8]. Few studies in humans have calculated this index, due to the need for independent measures of insulin secretion and sensitivity. To date, impaired insulin secretion relative to insulin sensitivity in IUGR or low birth weight populations compared to controls has been demonstrated in young adult men, children at 3 years of age, and children at 9 years of age who had rapid BMI gain [13–15]. This provides evidence that impaired insulin secretion and a poor capacity for insulin secretion to adapt to decreasing insulin sensitivity (impaired plasticity of insulin secretion) contribute to the increased risk of T2D after IUGR in humans (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

IUGR and insulin action in humans. Restriction of growth before birth enhances insulin sensitivity in neonates with reversal to impaired insulin sensitivity by adulthood. Insulin secretion is impaired from early postnatal life, and together these contribute to increased risks of T2D in the adult who was small at birth. Effects of IUGR/SGA are relative to AGA individuals, who are indicated by the thick dashed line. The dotted vertical line indicates birth.

4. Animal studies of restricted placental function

Placental dysfunction is implicated as a major cause of human IUGR and programming of health in later life (reviewed by Ref. [16]). In a recent large prospective population study, a high placental:fetal weight ratio at birth, suggestive of impaired placental function, was associated with increased mortality from cardiovascular disease, consistent with placental involvement in prenatal programming of adult disease in humans [17]. Two key animal models of restricted placental growth have therefore been developed to directly test the role of restricted placental growth and function in later disease. Excitingly, these PR models produce strikingly similar outcomes to human IUGR, particularly in regard to insulin action in later life, despite differences between these species in placental structure (haemomonochorial discoid placenta in human, haemotrichorial discoid placenta in rat and synepitheliochorial cotyledonary placenta in sheep [18,19]), litter size (monotocous in human, monotocous or twin-bearing in sheep, polytocous in rat), and maturity at birth (altricial in rat compared to human or sheep). In particular, this review will focus on use of these models to investigate the effects of restricted placental growth and function on diabetes and impaired insulin action, to investigate the underlying mechanisms for this, and excitingly, their recent use to test interventions to alleviate the risk of diabetes and impaired insulin action after IUGR.

4.1. The placentally restricted sheep

In the sheep, placental restriction can be induced from before conception, by surgical removal of the majority of endometrial caruncles (placental implantation sites) from non-pregnant females, to leave only 3–4 visible caruncles per uterine horn [20,21]. This reduces the number of placental cotyledons from between 60 and 100 to between 20 and 40 (due to caruncles within the tip and cervix of the uterine horn in addition to visible caruncles retained at surgery), and reduces total placental weight in the subsequent pregnancy by 15–72% [20–22]. Compensatory growth occurs in remaining placentomes, particularly increased growth of fetal tissue, which surrounds the maternal part of the placentome earlier in PR pregnancies than in control pregnancies [20–22]. Placental transport efficiencies of glucose and amino acids are also enhanced in the PR pregnancy [23]. Nevertheless, PR reduces placental blood flow, with ~40–50% and 50–70% lower late gestation umbilical and uterine blood flows, respectively [24,25]. Consequently, PR reduces fetal supplies of oxygen and nutrients, with a 25–40% reduction in the partial pressure of oxygen and 50% reduction in plasma glucose in the small PR fetus, and 50–60% reduction in fetal glucose turnover, relative to controls [22,25–27]. Like the IUGR human fetus, the ovine PR fetus has reduced circulating levels and expression of anabolic hormones including IGF-I and -II, and an early and greater surge in circulating cortisol in late gestation [28–31]. Size at birth is reduced by ~25% in the PR sheep, and importantly, this is followed by accelerated neonatal catch-up growth, similar to that seen in human IUGR, which occurs in association with increased insulin action [32–34]. Like the IUGR human, the PR sheep has enhanced fat deposition in early postnatal life, which may contribute to later development of disease [6,34].

We have recently reported that the PR sheep, like the IUGR human, develops impaired insulin secretion relative to demand for insulin [35]. Before birth, basal insulin disposition is normal, whilst glucose-stimulated insulin disposition is enhanced in small fetuses, which have reduced β-cell mass in proportion to their body weight [35,36]. In young suckling lambs, at ~30 d of age, insulin disposition in the basal state, although not when challenged by glucose, is negatively related to birth weight, being highest in low birth weight lambs [34,35]. With ageing, this relationship reverses, and insulin disposition in both basal and challenged states is positively related to birth weight in adult males [35,37]. Surprisingly, β-cell mass is up-regulated in the adult male IUGR sheep with impaired insulin secretion [35]. This is preceded by increased expression of known regulators of β-cell mass in young PR lambs, with insulin and IGF-II expression in particular identified as positively related to β-cell mass at the younger age [35]. Thus in the sheep, as in the human with poor insulin sensitivity [38], β-cell mass is up-regulated in response to long-term increased demand for insulin. Despite this increase in β-cell mass, insulin secretion is impaired in the adult male IUGR sheep due to severe impairment of β-cell function [35]. β-cell function in the young lamb is strongly and positively predicted by expression of CACNA1D, the gene for the α1D calcium-channel subunit, and this is down-regulated in the PR lamb, implicating altered regulation of this gene as a novel mechanism for impaired insulin secretion after IUGR [35].

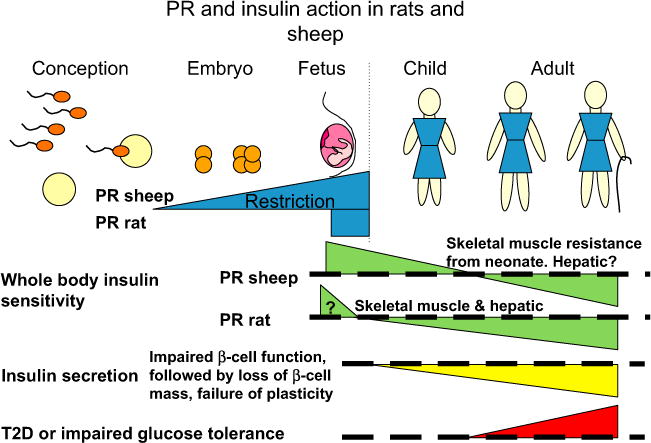

In contrast to insulin secretion, whole-body insulin sensitivity is not impaired in the young PR sheep. The insulin sensitivity of glucose metabolism is normal in late gestation PR fetuses [36]. Whole-body insulin sensitivity of glucose metabolism is enhanced in the young IUGR lamb in conjunction with catch-up growth, whilst the enhanced insulin sensitivity of adipose tissue in these animals may contribute to their increased fat deposition [34]. This net increase in whole-body insulin sensitivity, however, conceals differential changes in insulin sensitivity of individual tissues. Using tracer studies, we have recently shown that although hepatic insulin sensitivity is increased in the IUGR lamb, muscle insulin sensitivity is already reduced (De Blasio et al., unpublished). Consistent with this, down-regulation of genes within the insulin signalling, glucose uptake and glucose metabolism pathways is much more severe and widespread in skeletal muscle than in liver [39].

4.2. The placentally restricted rat

Placental restriction in rodents has also been used extensively in studies of outcomes of IUGR, their mechanistic basis and intervention strategies. In the rat or mouse, uterine blood flow can be surgically restricted by uni- or bi-lateral uterine artery ligation in late gestation (day 17 or 18, term ~day 21), producing severe restriction of nutrient and oxygen delivery to fetuses [40]. In at least some studies, this model of PR causes death of fetuses closest to the ligature site, and in general the degree of growth restriction that is induced is greater for fetuses closest to the ligature site near the base of the uterine horn than for those nearer the cervix [40]. Although in these early studies, Wigglesworth did not find reduced placental weights, in contrast to the PR sheep and many IUGR humans, others have reported ~15% lower placental weights in PR rat pregnancies [40,41]. The PR rat also shares many features of human IUGR, including reduced nutrient supply to the fetus with reduced placental transfer of glucose and amino acids [42], reduced circulating IGF-I [43] and a proportional reduction in pancreas weight and β-cell mass [44]. Unlike the PR sheep, placental blood flows appear to be only temporarily reduced following uterine artery ligation. PR in the rat reduces size at birth and is followed by catch-up growth and increased fat deposition, although effects on postnatal growth patterns vary between studies and with nutrition during lactation [45–47]. Consequently, the PR rat may experience catch-up growth after weaning [45,46] or may remain small [47], in contrast to the IUGR human where catch-up growth occurs during early postnatal life up to 2 years of age, and mostly within the first year of postnatal life [48,49].

Postnatally, the male PR rat develops progressive impairment of glucose homeostasis, in our hands progressing to frank diabetes by young adulthood at 26 weeks of age [45]. The majority of studies have reported impaired glucose tolerance in male PR progeny by adulthood [45–47], although one group reported elevated fasting glucose at 3–4 months of age in PR females, but not males [50]. Consistent with the PR sheep and IUGR human, there is evidence that insulin secretion defects as well as poor insulin sensitivity impair glucose homeostasis in the PR rat. Insulin secretion during a glucose tolerance test is impaired from early postnatal life in the PR rat, before development of fasting hyperglycaemia, and 1st phase insulin secretion loss is the first defect seen [45,47]. Impaired β-cell function must account for the first impairment insulin secretion, seen at 1 week of age, since β-cell mass in PR males first decreases below controls at around 7 weeks of age with progressive worsening to >80% loss of β-cells by 26 weeks of age [45].

This model has allowed us to demonstrate that altered epigenetic state in fetal life contributes to development of diabetes after birth. Epigenetic changes in DNA and associated chromatin, which alter gene expression without changes in DNA sequence, are postulated as central mechanisms by which environmental insults in fetal life might cause permanent changes in gene expression [51]. PR causes DNA hypomethylation and increased acetylation of histone H3 in fetal rat liver and brain [52,53]. DNA hypomethylation in PR fetuses is associated with decreased expression of DNA-methylating enzymes, and with increased circulating S-adenosylhomocysteine, which down-regulates their action [52]. We have now shown in the rat that PR induces progressive epigenetic changes in the promoter of Pdx-1, a transcription factor essential for β-cell development and plasticity of β-cell mass and function after birth [54]. In vitro reversal of epigenetic modifications in neonatal PR rat islets normalises Pdx-1 expression [54]. Mitochondrial dysfunction is also implicated in β-cell failure with ageing in the PR rat [55].

Impaired insulin sensitivity also contributes to development of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in the PR rat. Indirect and direct measures of whole-body insulin sensitivity are reduced in neonates, young and mature adult male PR rats [45,47,56], although young adult females have normal insulin sensitivity, calculated indirectly from fasting glucose and insulin [47]. Decreased whole-body insulin sensitivity appears to reflect changes in both hepatic and skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in the PR rat. Insulin is less able to suppress hepatic glucose production in young adult PR males than in controls, and basal hepatic glucose production is also elevated in these rats [56]. This reduced hepatic insulin sensitivity may be caused by the increased expression and protein levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1 in liver of newborn and weanling PR rats [57]. Evidence for poor skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in PR rats is indirect, with reduced content of insulin receptor protein, elevated PGC-1 protein and mRNA and reduced expression of enzymes important for long-chain fatty acid formation and oxidation, in neonatal hind limb skeletal muscle [58,59].

Thus, the PR rat and PR sheep develop similar defects in insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity as the IUGR human (Fig. 2). We therefore consider that these species provide useful tools in which to develop and test interventions to prevent or ameliorate impaired insulin action after IUGR.

Fig. 2.

PR and insulin action in sheep and rats. PR rats and sheep exhibit similar changes in insulin secretion and sensitivity with ageing as IUGR humans, including decreasing insulin sensitivity and impaired insulin secretion. Effects of PR are relative to control individuals, who are indicated by the thick dashed line. The dotted vertical line indicates birth.

5. Future directions: interventions to restore insulin action after IUGR

Given the evidence that epigenetic changes are pivotal in at least some placental programming of later disease, researchers have begun to test two alternate approaches to prevent this; first, reversing these epigenetic changes in early postnatal life, before they become permanent, and second, preventing or reducing the initial epigenetic changes by manipulating fetal methyl donor supply.

5.1. Neonatal exendin-4

Exendin-4 is a longer-lasting analogue of glucagon-like peptide-1, a gut hormone and member of the incretin family. It improves insulin action through a number of pathways, including increasing β-cell mass and function and decreasing appetite and food intake, hence reducing fat deposition, and is used in adult diabetics to improve glycaemic control [60]. At least some of these actions are via induction of Pdx-1 expression in β-cells [61]. Excitingly, a 6-day neonatal course of exendin-4 (1 nmol kg−1 d−1) prevents the development of diabetes in the PR rat, normalising glucose tolerance after birth, from early life through to mature adulthood [62]. This occurs in conjunction with normalisation of β-cell mass and Pdx-1 expression [62]. We have published our preliminary data showing that this induction of Pdx-1 by neonatal exendin-4 also normalises the epigenetic state of the Pdx-1 promoter, probably allowing postnatal expression to be maintained at control levels [63]. In our recent studies in the twin IUGR lamb, neonatal exendin-4 treatment from 1 to 16 days after birth (1 nmol kg−1 d−1) reduced fat deposition and growth during treatment [64], similar to responses in neonatal PR rats and in diabetic humans [60,62]. Critically, although this neonatal treatment corresponds to a later period of pancreatic development in the sheep than in the rat, exendin-4 increased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by 155% in the twin IUGR lamb [64]. This suggests that this intervention may also be effective in the human baby born after IUGR, as the neonatal human pancreas at a similar stage of development as the neonatal lamb. In both humans and the sheep, most pancreatic development takes place before birth, with β-cells developed by 0.25 gestation, islets in mid-gestation and substantial remodelling to a mature endocrine pancreas by near term, maturation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from mid-pregnancy and increasing secretion in late gestation [36,65–73]. In contrast, the fetal rat pancreas does not develop insulin-containing cells until the second half of gestation, and pancreatic remodelling with peaks in replication and apoptosis occur in the early postnatal period at 1–2 weeks of age [68,74].

5.2. Maternal dietary methyl donor and cofactor supplementation

Given the perturbed epigenetic state of the PR rat, described earlier, we have also performed pilot studies in the sheep to assess the potential for normalising epigenetic state and insulin action by increasing the fetal supply of methyl donors and cofactors. Direct evidence already existed to show that maternal methyl donor and cofactor status could be manipulated by altering maternal nutrition in this species, with long-term effects on progeny phenotype and epigenetic state. In an elegant series of studies, Sinclair et al. decreased maternal levels of methyl donors and Vitamin B12 by severe restriction of maternal sulphur and cobalt intake, which provide the substrates for ruminal production of sulphated amino acids (including methionine) and Vitamin B12, respectively [75]. Maternal Co and S deficiency of donor ewes during oocyte and preimplantation development, followed by embryo transfer to control ewes, programmed impaired insulin sensitivity and elevated blood pressure in adult progeny, particularly males [75]. This also altered the methylation status of ~4% of 1400 known CpG islands in fetal liver in late gestation [75]. Excitingly, when we gave ewes a dietary supplement containing rumen-protected methionine, folate, cobalt and sulphur for the last month of pregnancy (maternal methyl donor supplementation, MMDS), their growth-restricted twin offspring had increased numbers of β-cells at 16 d of age, and were more insulin sensitive than controls or IUGR twin lambs from un-supplemented ewes [76]. This suggests that MMDS during late pregnancy may also improve insulin action postnatally, and we are now evaluating the long-term consequences of maternal methyl donor supplementation in the IUGR sheep.

6. Conclusion

Studies in the placentally restricted sheep and rat have shown that impaired placental growth and function induces similar postnatal phenotypes as follow IUGR in humans, including poor insulin sensitivity and impaired insulin secretion relative to demand. These support a role for the placenta in prenatal programming of metabolic disease. Extensive studies of the underlying mechanisms for impaired insulin action in the PR rat and sheep have provided the basis for designing interventions to prevent diabetes after IUGR, with promising results from initial studies of neonatal exendin-4 and maternal dietary supplementation with methyl donors and cofactors in late pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of our research groups and our collaborators who have contributed to these studies. The authors thank the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and Diabetes Australia Research Trust for their funding of our studies in PR and IUGR sheep (KLG, MJD, JSR, JAO) and the National Institutes of Health, USA, for funding of our studies in the PR rat (RAS). The sponsors were not involved in data collection, analysis and interpretation or writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any potential or actual personal, political, or financial interest in the material, information, or techniques described in this paper.

References

- 1.Newsome CA, Shiell AW, Fall CHD, Phillips DIW, Shier R, Law CM. Is birth weight related to later glucose and insulin metabolism? – a systemic review. Diabet Med. 2003;20:339–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harder T, Rodekamp E, Schellong K, Dudenhausen JW, Plagemann A. Birth weight and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(8):849–57. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whincup PH, Kaye SJ, Owen CG, Huxley R, Cook DG, Anazawa S, et al. Birth weight and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300(24):2886–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaijser M, Edstedt Bonamy A-K, Akre O, Cnattingius S, Granath F, Norman M, et al. Perinatal risk factors for diabetes in later life. Diabetes. 2009;58(3):523–6. doi: 10.2337/db08-0558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson M, Wallander M-A, Krakau I, Wedel H, Svardsudd K. Birth weight and cardiovascular risk factors in a cohort followed until 80 years of age: the study of men born in 1913. J Intern Med. 2004;255(2):236–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ong KKL, Ahmed ML, Emmett PM, Preece MA, Dunger DB. Association between postnatal catch-up growth and obesity in childhood: prospective cohort study. Br Med J. 2000;320:967–71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7240.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belfiore F, Iannello S. Insulin resistance in obesity: metabolic mechanisms and measurement methods. Mol Genet Metab. 1998;65:121–8. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1998.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergman RN, Ader M, Huecking K, Van Citters G. Accurate assessment of β-cell function. The hyperbolic correction. Diabetes. 2002;51(Suppl. 1):S212–20. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaquet D, Gaboriau A, Czernichow P, Levy-Marchal C. Insulin resistance early in adulthood in subjects born with intrauterine growth retardation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1401–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.4.6544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bazaes RA, Salazar TE, Pittaluga E, Pena V, Alegria A, Iniguez G, et al. Glucose and lipid metabolism in small for gestational age infants at 48 hours of age. Pediatrics. 2003;111:804–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soto N, Bazaes RA, Pena V, Salazar TE, Avila A, Iniguez G, et al. Insulin sensitivity and secretion are related to catch-up growth in small-for-gestational-age infants at age 1 year: results from a prospective cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3645–50. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-030031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ong KK, Petry CJ, Emmett PM, Sandhu MS, Kiess W, Hales CN, et al. Insulin sensitivity and secretion in normal children related to size at birth, postnatal growth, and plasma insulin-like growth factor-I levels. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1064–70. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mericq V, Ong KK, Bazaes R, Pena V, Avila A, Salazar T, et al. Longitudinal changes in insulin sensitivity and secretion from birth to age three years in small- and appropriate-for-gestational-age children. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2609–14. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen CB, Storgaard H, Dela F, Holst JJ, Madsbad S, Vaag AA. Early differential defects of insulin secretion and action in 19-year-old Caucasian men who had low birth weight. Diabetes. 2002;51:1271–80. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veening MA, van Weissenbruch MM, Heine RJ, Delemarre-van de Waal HA. β-cell capacity and insulin sensitivity in prepubertal children born small for gestational age. Influence of body size during childhood. Diabetes. 2003;52:1756–60. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myatt L. Placental adaptive responses and fetal programming. J Physiol. 2006;572(1):25–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.104968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Risnes KR, Romundstad PR, Nilsen TIL, Eskild A, Vatten LJ. Placental weight relative to birth weight and long-term cardiovascular mortality: findings from a cohort of 31,307 men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(5):622–31. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steven DH. Anatomy of the placental barrier. In: Steven DH, editor. Comparative placentation: essays in structure and function. London: Academic Press; 1975. pp. 25–57. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enders AC, Carter AM. What can comparative studies of placental structure tell us? – a review. Placenta. 2004;25(Suppl. 1):S3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander GR. Studies on the placenta of the sheep (Ovis aries L.). Effect of surgical reduction in the number of caruncles. J Reprod Fertil. 1964;7:307–22. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0070307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson JS, Kingston EJ, Jones CT, Thorburn GD. Studies on experimental growth retardation in sheep. The effect of removal of endometrial caruncles on fetal size and metabolism. J Dev Physiol. 1979;1:379–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harding JE, Jones CT, Robinson JS. Studies on experimental growth restriction in sheep. The effects of a small placenta in restricting transport to and growth of the fetus. J Dev Physiol. 1985;7:427–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owens JA, Falconer J, Robinson JS. Restriction of placental size in sheep enhances efficiency of placental transfer of antipyrine, 3-O-methyl-D-glucose but not of urea. J Dev Physiol. 1987;9:457–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owens JA, Falconer J, Robinson JS. Effect of restriction of placental growth on umbilical and uterine blood flows. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:R427–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.250.3.R427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owens JA, Falconer J, Robinson JS. Effect of restriction of placental growth on oxygen delivery to and consumption by the pregnant uterus and fetus. J Dev Physiol. 1987;9:137–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owens JA, Falconer J, Robinson JS. Effect of restriction of placental growth on fetal and utero-placental metabolism. J Dev Physiol. 1987;9:225–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens JA, Falconer J, Robinson JS. Glucose metabolism in pregnant sheep when placental growth is restricted. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:R350–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.2.R350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones CT, Boddy K, Robinson JS. Changes in the concentration of adrenocorticotrophin and corticosteroid in the plasma of foetal sheep in the latter half of pregnancy and during labour. J Endocrinol. 1977;72:293–300. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0720293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Owens JA, Kind KL, Carbone F, Robinson JS, Owens PC. Circulating insulin-like growth factors-I and -II and substrates in fetal sheep following restriction of placental growth. J Endocrinol. 1994;140:5–13. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kind KL, Owens JA, Robinson JS, Quinn KJ, Grant PA, Walton PE, et al. Effect of restriction of placental growth on expression of IGFs in fetal sheep: relationship to fetal growth, circulating IGFs and binding proteins. J Endocrinol. 1995;146:23–34. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1460023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips ID, Simonetta G, Owens JA, Robinson JS, Clarke IJ, McMillen C. Placental restriction alters the functional development of the pituitary–adrenal axis in the sheep fetus during late gestation. Pediatr Res. 1996;40:861–6. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199612000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albertsson-Wikland K, Karlberg J. Postnatal growth of children born small for gestational age. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1997;423:193–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb18413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Blasio MJ, Gatford KL, Robinson JS, Owens JA. Placental restriction of fetal growth reduces size at birth and alters postnatal growth, feeding activity and adiposity in the young lamb. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:R875–86. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00430.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Blasio MJ, Gatford KL, McMillen IC, Robinson JS, Owens JA. Placental restriction of fetal growth increases insulin action, growth and adiposity in the young lamb. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1350–8. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gatford KL, Mohammad SNB, Harland ML, De Blasio MJ, Fowden AL, Robinson JS, et al. Impaired β-cell function and inadequate compensatory increases in β-cell mass following intrauterine growth restriction in sheep. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5118–27. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owens JA, Gatford KL, De Blasio MJ, Edwards LJ, McMillen IC, Fowden AL. Restriction of placental growth in sheep impairs insulin secretion but not sensitivity before birth. J Physiol. 2007;584:935–49. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owens JA, Thavaneswaran P, De Blasio MJ, McMillen IC, Robinson JS, Gatford KL. Sex-specific effects of placental restriction on components of the metabolic syndrome in young adult sheep. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:E1879–89. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00706.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonner-Weir S. Islet growth and development in the adult. J Mol Endocrinol. 2000;24(3):297–302. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0240297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Owens JA, Harland ML, De Blasio MJ, Gatford KL, Robinson JS. Restriction of placental and fetal growth reduces expression of insulin signalling and glucose transporter genes in skeletal muscle of young lambs. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83:S134. [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wigglesworth J. Experimental growth retardation in the foetal rat. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1964;88:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruce NW. The effect on fetal development and utero-placental blood flow of ligating a uterine artery in the rat near term. Teratology. 1977;16:327–31. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420160312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nitzan M, Orloff S, Schulman JD. Placental transfer of analogs of glucose and amino acids in experimental intrauterine growth retardation. Pediatr Res. 1979;13:100–3. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vileisis RA, D’Ercole AJ. Tissue and serum concentrations of somatomedin-C/insulin-like growth factor I in fetal rats made growth retarded by uterine artery ligation. Pediatr Res. 1986;20:126–30. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198602000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Prins FA, Van Assche FA. Intrauterine growth retardation and development of endocrine pancreas in the experimental rat. Biol Neonate. 1982;41:16–21. doi: 10.1159/000241511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simmons RA, Templeton LJ, Gertz SJ. Intrauterine growth retardation leads to the development of type 2 diabetes in the rat. Diabetes. 2001;50:2279–86. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.10.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nusken K-D, Dotsch J, Rauh M, Rascher W, Schneider H. Uteroplacental insufficiency after bilateral uterine artery ligation in the rat: impact on postnatal glucose and lipid metabolism and evidence for metabolic programming of the offspring by sham operation. Endocrinology. 2008;149(3):1056–63. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siebel AL, Mibus AL, De Blasio MJ, Westcott KT, Morris MJ, Prior L, et al. Improved lactational nutrition and postnatal growth ameliorates impairment of glucose tolerance by uteroplacental insufficiency in male rat offspring. Endocrinology. 2008;149(6):3067–76. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albertsson-Wikland K, Karlberg J. Natural growth in children born small for gestational age with and without catch-up growth. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1994;399:64–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karlberg JPE, Albertsson-Wikland K, Kwan EYW, Lam BCC, Low LCK. The timing of early postnatal catch-up growth in normal, full-term infants born short for gestational age. Horm Res. 1997;48(Suppl. 1):17–24. doi: 10.1159/000191279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jansson T, Lambert GW. Effect of intrauterine growth restriction on blood pressure, glucose tolerance and sympathetic nervous system activity in the rat at 3–4 months of age. J Hypertens. 1999;17:1239–48. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simmons RA. Developmental origins of beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes: the role of epigenetic mechanisms. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:64R–7R. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e3180457623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.MacLennan NK, James SJ, Melnyk S, Piroozi A, Jernigan S, Hsu JL, et al. Ute-roplacental insufficiency alters DNA methylation, one-carbon metabolism, and histone acetylation in IUGR rats. Physiol Genomics. 2004;18:43–50. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00042.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ke X, Lei Q, James SJ, Kelleher SL, Melnyk S, Jernigan S, et al. Uteroplacental insufficiency affects epigenetic determinants of chromatin structure in brains of neonatal and juvenile IUGR rats. Physiological Genomics. 2006;25(1):16–28. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00093.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park JH, Stoffers D, Nicholls RD, Simmons RA. Development of type 2 diabetes following intrauterine growth retardation in rats is associated with progressive epigenetic silencing of Pdx1. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2316–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI33655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simmons RA, Suponitsky-Kroyter I, Selak MA. Progressive accumulation of mitochondrial DNA mutations and decline in mitochondrial function lead to β-cell failure. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28785–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vuguin P, Raab E, Liu B, Barzilai N, Simmons R. Hepatic insulin resistance precedes the development of diabetes in a model of intrauterine growth retardation. Diabetes. 2004;53:2617–22. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lane RH, MacLennan NK, Hsu JL, Janke SM, Pham TD. Increased hepatic Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ Coactivator-1 gene expression in a rat model of intrauterine growth retardation and subsequent insulin resistance. Endocrinology. 2002;143(7):2486–90. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.7.8898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Germani D, Puglianiello A, Cianfarani S. Uteroplacental insufficiency down regulates insulin receptor and affects expression of key enzymes of long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) metabolism in skeletal muscle at birth. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2008;7(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lane RH, Maclennan NK, Daood MJ, Hsu JL, Janke SM, Pham TD, et al. IUGR alters postnatal rat skeletal muscle peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 gene expression in a fiber specific manner. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:994–1000. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000064583.40495.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nauck MA, Meier JJ. Glucagon-like peptide 1 and its derivatives in the treatment of diabetes. Regul Pept. 2005;128(2):135–48. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Doyle ME, Egan JM. Mechanisms of action of glucagon-like peptide 1 in the pancreas. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113(3):546–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stoffers DA, Desai BM, De Leon DD, Simmons RA. Neonatal exendin-4 prevents the development of diabetes in the intrauterine growth retarded rat. Diabetes. 2003;52:734–40. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pinney SE, Niu H, Li F, Simmons RA. Neonatal exendin-4 administration normalises epigenetic modifications of the proximal promoter of Pdx-1. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(Suppl. 1):S71. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gatford KL, Sulaiman SA, Mohammad SNB, De Blasio MJ, Harland ML, Owens JA. Interventions to prevent diabetes after IUGR – preliminary outcomes in the twin IUGR lamb. Fetal and Neonatal Physiology Workshop, Darwin. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Willes RF, Boda JM, Stokes H. Cytological localization of insulin and insulin concentration in the fetal ovine pancreas. Endocrinology. 1969;84:671–5. doi: 10.1210/endo-84-3-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bassett JM. Glucagon, insulin and glucose homeostasis in the fetal lamb. Ann Rech Vet. 1977;8(4):362–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fowden AL. Effects of arginine and glucose on the release of insulin in the sheep fetus. J Endocrinol. 1980;85:121–9. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0850121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reddy S, Elliot RB. Ontogenic development of peptide hormones in the mammalian fetal pancreas. Experientia. 1988;44:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01960221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Otonkoski T, Andersson S, Knip M, Simell O. Maturation of insulin response to glucose during human fetal and neonatal development. Studies with perfusion of pancreatic islet like cell clusters. Diabetes. 1988;37(3):286–91. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kassem S, Ariel I, Thornton P, Scheimberg I, Glaser B. β-cell proliferation and apoptosis in the developing normal human pancreas and in hyperinsulinism of infancy. Diabetes. 2000;49(8):1325–33. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.8.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Piper K, Brickwood S, Turnpenny LW, Cameron IT, Ball SG, Wilson DI, et al. Beta cell differentiation during early human pancreas development. J Endocrinol. 2004;181(1):11–23. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1810011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Limesand SW, Jensen J, Hutton JC, Hay WW., Jr Diminished β-cell replication contributes to reduced β-cell mass in fetal sheep with intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol. 2005;288(5):R1297–305. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00494.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rozance PJ, Limesand SW, Hay WW. Decreased nutrient-stimulated insulin secretion in chronically hypoglycemic late-gestation fetal sheep is due to an intrinsic islet defect. Am J Physiol. 2006;291(2):E404–11. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00643.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scaglia L, Cahill CJ, Finegood DT, Bonner-Weir S. Apoptosis participates in the remodelling of the endocrine pancreas in the neonatal rat. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1736–41. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.4.5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sinclair KD, Allegrucci C, Singh R, Gardner DS, Sebastian S, Bispham J, et al. DNA methylation, insulin resistance, and blood pressure in offspring determined by maternal periconceptional B vitamin and methionine status. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(49):19351–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707258104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gatford KL, Mohammad SNB, Sulaiman SA, De Blasio MJ, Harland ML, Owens JA. Effects of maternal folate supplementation in late pregnancy on insulin sensitivity and β-cell number in the IUGR lamb. Adelaide, Australia: Australian Diabetes Society Annual Scientific Meeting; 2009. p. 264. [abstract] [Google Scholar]