Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of when silencing HOTAIR in ovarian cancer skov3 cells on proliferation, migration, and invasion, and to elucidate the mechanism by which this occurs.

Material/Methods

We detected the mRNA level of HOTAIR (HOX antisense intergenic RNA) and MAPK1 (mitogen-activated protein kinase 1) in ovarian cancer SKOV3, ES-2, OVCAR3, A2780, and COC1 cell lines. We detected the mRNA level of HOTAIR and MAPK1 in ovarian SKOV3 when transected with miR-1, miR-214-3p, or miR-330-5p. We detected the mRNA and protein level of MAPK1 when silencing HOTAIR. We detected the expression of HOTAIR when silencing MAPK1. Then we detected the proliferation, migration, and invasion in ovarian cancer skov3 after silencing HOTAIR or MAPK1.

Results

The expression of HOTAIR and MAPK1 in ovarian SKOV3, ES-2, and OVCAR3 increased compared with A2780 and COC1 cells (P<0.05). The mRNA level of HOTAIR and MAPK1 in ovarian SKOV3 decreased when transected with miR-1, miR-214-3p, or miR-330-5p compared to negative control (p<0.05). The mRNA and protein level of MAPK1 was decreased when silencing HOTAIR and the mRNA level of HOTAIR was decreased when silencing MAPK1 (p<0.05). The proliferation, migration, and invasion was inhibited in ovarian SKOV3 after silencing HOTAIR or MAPK1 (p<0.05).

Conclusions

HOTAIR can promote proliferation, migration, and invasion in ovarian SKOV3 cells as a competing endogenous RNA.

MeSH Keywords: MicroRNAs; Ovarian Neoplasms; RNA, Long Noncoding

Background

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the most lethal gynecologic malignancy in adult women and causes cancer-related deaths in women worldwide [1–4]. EOC is characterized by the frequent development of metastases in the abdominal cavity and pelvis during the early stage of the disease [2,5]. As a result, over 75% of EOC patients have already developed metastases when they are first diagnosed. Despite advances in surgery and chemotherapy, the overall survival of EOC patients remains unsatisfactory. The 5-year survival rate is about 30% [6]. The poor prognosis of patients with EOC has been related to the occurrence of tumor metastasis and recurrence. Thus, it is crucial to understand the molecular mechanisms involved in EOC metastasis and it is important to identify biomarkers of EOC for diagnosis and prediction of clinical outcome.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs, >200 nt in length) were initially thought to represent spurious transcriptional noise. However, some lncRNAs have been shown to regulate gene expression at various levels, including in chromatin modification, transcription, and posttranscriptional processing [7,8]. The lncRNA Xist is a potent tumor suppressor of hematologic malignancies. lincRNA PCAT-1 was overexpressed in high-grade and metastatic tumors and PCAT-1 promoted proliferation of prostate cancer cells [9]. HOTAIR is an lncRNA transcribed from the HOXC locus. It can repress transcription of HOXD in foreskin fibroblasts [10]. HOTAIR is involved in primary breast tumors and breast cancer metastases. Furthermore, HOTAIR expression positively correlates with malignant processes and poor outcome in colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and ovarian cancer [11–15]. However, the underlying molecular mechanism of HOTAIR in ovarian cancer remains under investigation.

Recently, a new regulatory mechanism has been identified – crosstalk between lncRNAs and mRNAs occurs by competing for shared microRNAs (miRNAs) response elements. lncRNAs may function as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) to sponge miRNAs, thereby regulating the derepression of miRNA targets and imposing an additional level of post-transcriptional regulation [16]. The MAPK pathway includes some key signaling components and phosphorylation events that play a role in tumorigenesis. These activated kinases transmit extracellular signals that regulate cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and migration functions. Alteration of the MAPK pathway has been reported in human cancer. This pathway is considered a potential therapeutic target for cancer treatment [17]. However, there is no report about the relation between MAPK and HOTAIR.

In this study, we report that HOTAIR may function as a ceRNA to regulate the expression of MAPK1 through competition for miR-1, miR-214-3p, or miR-330-5p in ovarian SKOV3 cells, providing a new insight in the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Material and Methods

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The patient and control groups had no significant differences in terms of age and parity (p>0.05). The tissue samples were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned (5-μm thickness), deparaffinized in xylene, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, subjected to antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0; Sigma) for 30 min in a steamer, and washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). PBS was used for all subsequent washes and for antiserum dilution. Tissue sections were quenched sequentially in 3% hydrogen peroxide and blocked with PBS containing 10% goat serum (sigma) for 1 h at 37°C. Next, slides were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C, which included Rabbit monoclonal (1:150; ab32081; Abcam). Negative controls included omission of primary antibody and use of irrelevant primary antibodies. After several washes (3×3 min) to remove excess antibody, the slides were incubated with diluted (1:300) anti-rabbit biotinylated antibodies (Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China) for 1 h. All the slides were washed in PBS and were incubated in avidin biotin peroxidase complex (ABC, Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) diluted 1:300 in PBS for 30 min in humidified chambers at 37°C. DAB (Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China) was used as a chromogen and hematoxylin was used as a nuclear counter-stain.

Slides were evaluated independently by 3 pathologists for distribution and intensity of signal as described by De Falco et al. [18]. Intensity was scored from 0 to 3: 0 (absent immunopositivity); 1 (low immunopositivity); 2 (moderate immunopositivity); and 3 (intense immunopositivity). An average of 22 fields was observed for each tissue.

Cell lines and culture conditions

Ovarian cancer cell lines (SKOV3, ES-2, OVCAR3, A2780, and COC1) were purchased from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 or DMEM (GIBCO-BRL) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10% FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) in humidified air at 37°C with 5% CO2. The miRNA mimics were purchased from Genepharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Negative control was transfected non-specific siRNA.

EdU assay

The proliferation of cells was detected by EdU assay as described by Yongmao Yu et al. [19].

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from ovarian cancer cell lines, using an RNA prep pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a PrimeScriptTM RT-PCR Kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology Co., Ltd). HOTAIR or MAPK1 mRNA expression levels were examined by quantitative real-time PCR with the iQ5 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and All-in-One qPCR Mix (GeneCopoeia, Inc.). β-actin values were used for normalization. Primers used for SYBR Green assay were purchased from GeneCopoeia, Inc. (HQP054911, HQP016381). PCR amplifications were started with a 10-min denaturation step at 95°C, followed by 40 amplification cycles (10 s at 95°C, 20 s at 60°C, and 10 s at 72°C). Relative quantification of mRNA was performed using the comparative threshold cycles (CT) method. For detecting miR-1, miR-214-3p, or miR-330-5p, reverse transcription was performed following GeneCopoeia protocol U6 snoRNA validated as the normalizer. The primers were purchased from GeneCopoeia. The value was used to plot the gene expression employing the formula 2−ΔΔCT.

Western blot analysis

Expression of MAPK1 protein was analyzed by Western blotting as previously described [20]. The primary antibodies used included polyclonal goat anti-MAPK1 (1:5000; ab32081; Abcam) and polyclonal rabbit anti-β-actin (1:500; ZA-0239; Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China). The bands were detected via enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China) and quantified by ImageQuant 3.3 software (Molecular Dynamics).

Statistical evaluation

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM. The Mann-Whitney U test was used. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

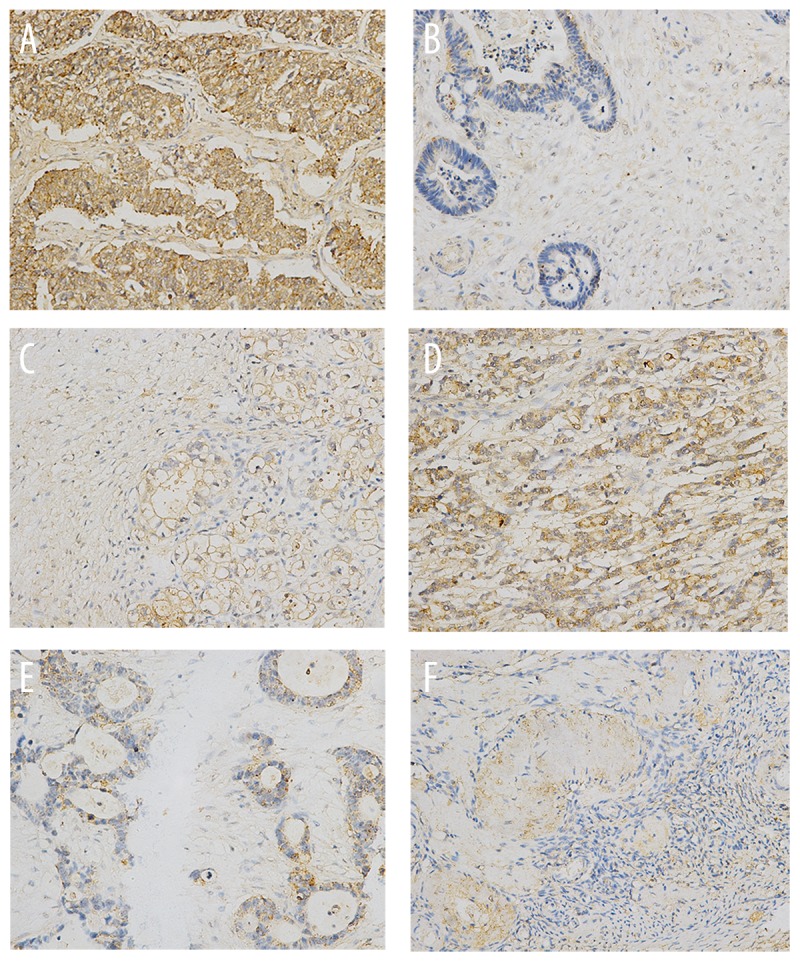

The expression of MAPK1 in ovarian cancer tissues

The expression of MAPK1 was significantly higher in ovarian carcinoma samples than normal ovarian samples (Figure 1 and Figure 2F; P<0.05). MAPK1 was predominantly localized on the plasma membrane, and cytoplasm (Figure 1A–1C).

Figure 1.

The expression of MAPK1 in ovarian cancer tissues. (A). Ovarian serous adenocarcinoma; (B). Endometrioid carcinoma; (C) Clear cell carcinoma; (D). Ovarian adenocarcinoma with metastasis; (E). Mucinous adenocarcinoma; (F). Normal ovarian tissues. ×200 magnification.

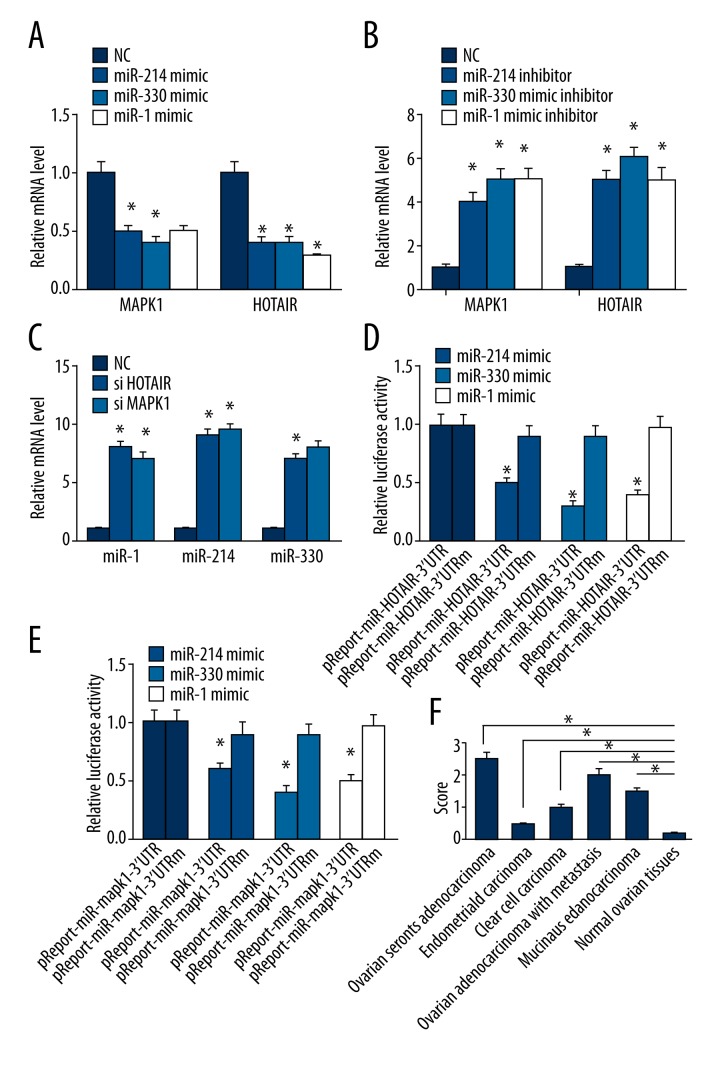

Figure 2.

The expression of mRNA and luciferase. * p<0.05 (versus control group); error bars, SEM.

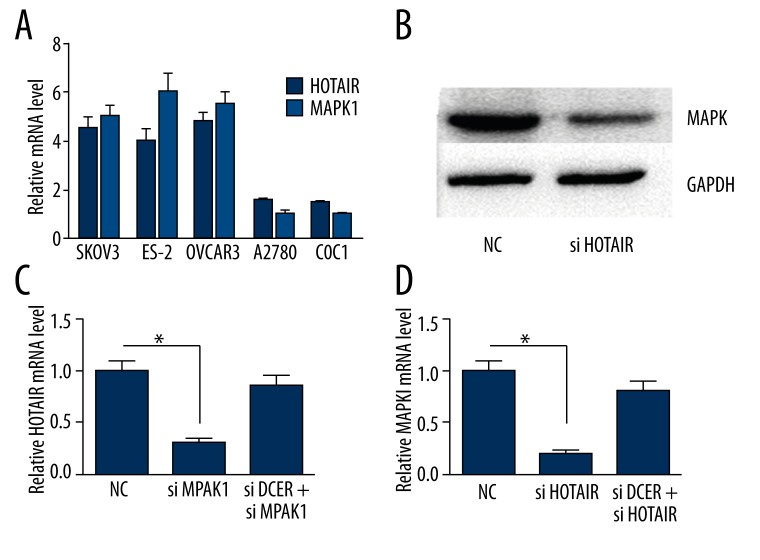

The expression of HOTAIR and MAPK1 in ovarian cancer cells

To investigate the expression of HOTAIR and MAPK1 in ovarian cancer cells, we detected the mRNA expression of HOTAIR and MAPK1 in SKOV3, ES-2, OVCAR3, A2780, and COC1 cells. The mRNA expression of HOTAIR and MAPK1 in ovarian SKOV3, ES-2, and OVCAR3 was increased compared with A2780 and COC1 cells (Figure 3A) (P<0.05).

Figure 3.

Cell proliferation was detected by EdU assay.

The interaction between HOTAIR and MAPK1 in ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells

We chose SKOV3 cells due to their high level expression of HOTAIR and MAPK1. The protein and mRNA level of MAPK1was decreased when silencing HOTAIR. The mRNA level of HOTAIR was decreased when silencing MAPK1 (P<0.05). When silencing dicer, the interaction between HOTAIR and MAPK1 was damaged (Figure 3B–D).

HOTAIR and MAPK1 are targets of miR-1, miR-214-3p, or miR-330-5p

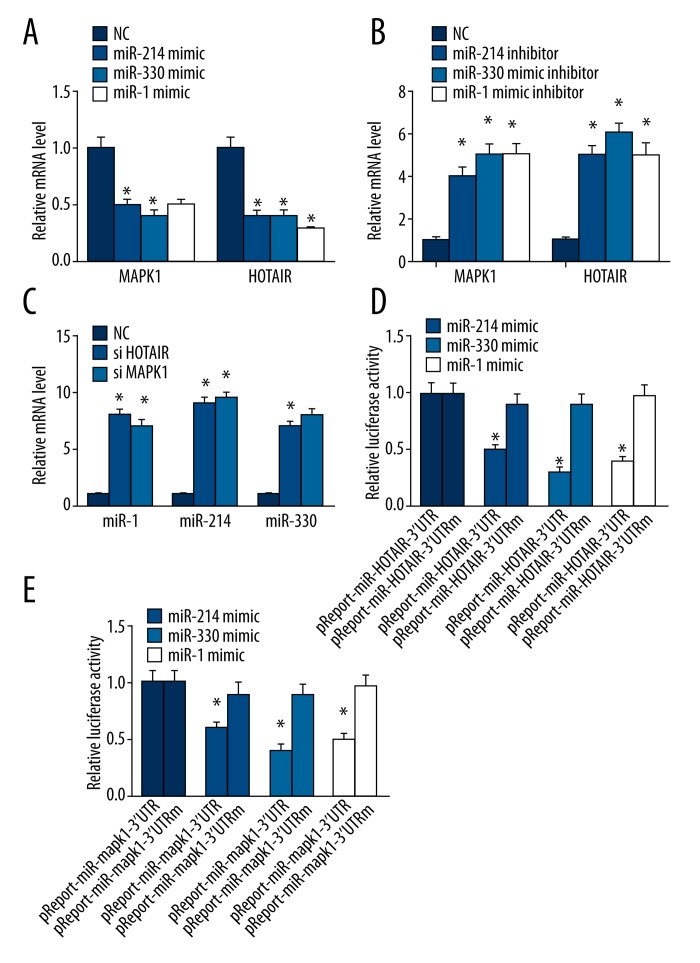

We sought to determine whether HOTAIR and MAPK1 are targets of miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p. MiR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p mimics and inhibitors were transfected into ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells. The expression of HOTAIR and MAPK1 was decreased when transfected with miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p mimics (Figure 4A) (P<0.05). In contrast, the expression of HOTAIR and MAPK1 was increased when transfection with miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p inhibitors (Figure 4B) (P<0.05). Luciferase assays confirmed the existence of specific crosstalk between the HOTAIR and MAPK1 mRNA through competition for miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p binding (Figure 4C, 4D).

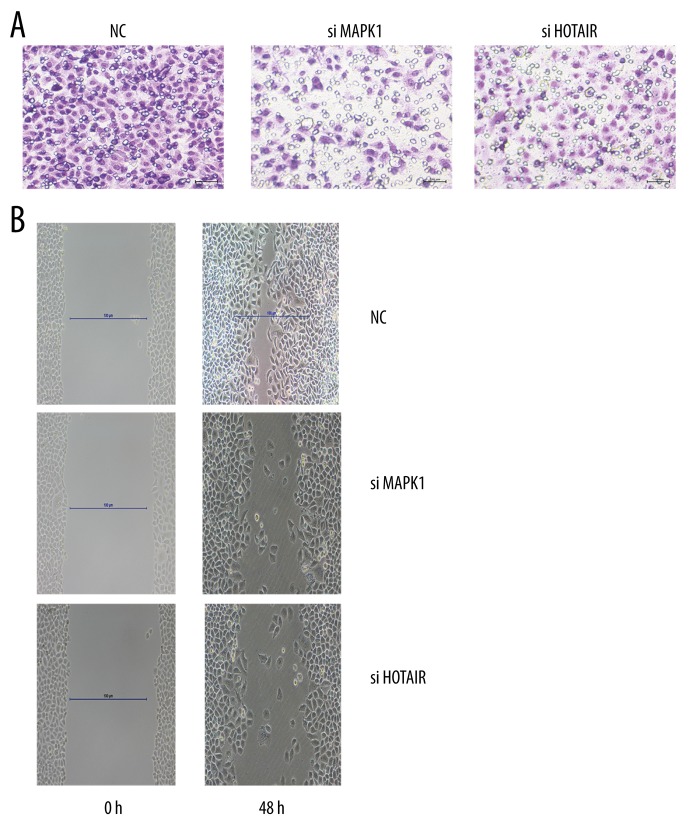

Figure 4.

The migration and invasion was detected. NC represented negative control.

Silencing HOTAIR or MAPK1 increased the expression of miR-1, miR-214-3p, or miR-330-5p

We sought to determine whether HOTAIR and MAPK1 regulate miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p. The expression of miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p was increased when HOTAIR or MAPK1 was silenced (Figure 2C) (P<0.05). The present work provides the first evidence for a positive HOTAIR/ MAPK1 correlation and the crosstalk between miR-1, miR-214-3p, miR-330-5p, HOTAIR, and MAPK1.

Silencing HOTAIR or MAPK1 inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion in SKOV3 cells

We investigated the effects of HOTAIR or MAPK1 on SKOV3 cells. The proliferation, migration, and invasion of SKOV3 was inhibited when HOTAIR and MAPK1 were silenced (Figures 2, 5) (P<0.05).

Figure 5.

The relative expression of mRNA and protein. * p<0.05 (versus control group); error bars, SEM.

Discussion

Long noncoding RNAs are a recently discovered class of non-protein coding RNAs, which are now increasingly been shown to be involved in a wide variety of biological processes as regulatory molecules. Recent reports have suggested that lncRNAs could potentially interact with other classes of non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs), and modulate their regulatory role through interactions [21].

In this study, we found that the expression of HOTAIR and MAPK1 in ovarian SKOV3, ES-2, and OVCAR3 was increased compared to expression in A2780 and COC1 cells. The repression of HOTAIR and MAPK1 were well correlated. Furthermore, we found that HOTAIR interacted with MAPK1 through miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p. The proliferation, migration, and invasion were inhibited in ovarian SKOV3 after silencing HOTAIR or MAPK1.

Emerging evidence suggests that lncRNAs may participate in this regulatory circuitry, and we hypothesized that HOTAIR may also serve as a ceRNA. Bioinformation analysis (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/) indicated that HOTAIR is a putative ceRNA of MAPK1. Firstly, we investigated the expression of MAPK1 and HOTAIR in ovarian cancer SKOV3, ES-2, OVCAR3, A2780, and COC1. We found that the expression of HOTAIR and MAPK1 in ovarian SKOV3, ES-2, and OVCAR3 was increased compared with A2780 and COC1 cells (P<0.05), suggesting that HOTAIR may be related to MAPK1. Silencing HOTAIR downregulated the protein and mRNA level of MAPK1 and silencing MAPK1 down-regulated the expression of HOTAIR, suggesting that HOTAIR may interact with MAPK1. When silencing dicer, the interaction between HOTAIR and MAPK1 was damaged; therefore, we hypothesized that miRNA may be involved in this process.

Bioinformation analysis predicts that miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p are shared by HOTAIR and MAPK1 [22,23]; therefore, we sought to determine whether the interaction of HOTAIR and MAPK1 is regulated by miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p. As expected, miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p mimics can inhibit the expression of HOTAIR and MAPK1. When silencing HOTAIR, the expression of miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p was increased, suggesting that the interaction of HOTAIR and MAPK1 is mediated through miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p.

The MAPK pathway is involved in the malignancy feature of ovarian cancer, including in proliferation, migration, and invasion [24–27]. These activated kinases transmit extracellular signals that regulate cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and migration functions. Alteration of the MAPK pathway has been reported in human cancer [17]. Overexpression of MAPK leads to ovarian cancer chemical resistance [28]. Our study revealed that silencing MAPK can inhibit proliferation, migration, and invasion in ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells, consistent with previous reports [28,29]. HOTAIR is overexpressed in many cancers, such as colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and ovarian cancer [11–15]. Down-regulation of HOTAIR can inhibit the malignant behavior of cancer [30]. In this study, silencing HOTAIR inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion of ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells.

Conclusions

Our study shows that HOTAIR interacting with MAPK1 regulates ovarian cancer skov3 cells proliferation, migration, and invasion through miR-1, miR-214-3p, and miR-330-5p, and can serve as a therapeutic target of ovarian cancer. This provides new insight in ovarian cancer research, pathogenesis, and treatment. In the future, we will study the interaction between HOTAIR and MAPK1 in vivo.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bast RC, Jr, Hennessy B, Mills GB. The biology of ovarian cancer: new opportunities for translation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(6):415–28. doi: 10.1038/nrc2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowtell DD. The genesis and evolution of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(11):803–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc2946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oshakbayev KP, Alibek K, Ponomarev IO, et al. Weight change therapy as a potential treatment for end-stage ovarian carcinoma. Am J Case Rep. 2014;15:203–11. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.890229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho HY, Kim K, Jeon YT, et al. CA19-9 elevation in ovarian mature cystic teratoma: discrimination from ovarian cancer – CA19-9 level in teratoma. Med Sci Monit. 2013;19:230–35. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rustin G, van der Burg M, Griffin C, et al. Early versus delayed treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2011;377(9763):380–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Y, Zhou Y. The role of surgery in the treatment of gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101(8):687–92. doi: 10.1002/jso.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilusz JE, Sunwoo H, Spector DL. Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes Dev. 2009;23(13):1494–504. doi: 10.1101/gad.1800909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eades G, Zhang YS, Li QL, et al. Long non-coding RNAs in stem cells and cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5(2):134–41. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, et al. Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2007;129(7):1311–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464(7291):1071–76. doi: 10.1038/nature08975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kogo R, Shimamura T, Mimori K, et al. Long noncoding RNA HOTAIR regulates polycomb-dependent chromatin modification and is associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancers. Cancer Res. 2011;71(20):6320–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geng YJ, Xie SL, Li Q, et al. Large intervening non-coding RNA HOTAIR is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma progression. J Int Med Res. 2011;39(6):2119–28. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niinuma T, Suzuki H, Nojima M, et al. Upregulation of miR-196a and HOTAIR drive malignant character in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Res. 2012;72(5):1126–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiu JJ, Lin YY, Ye LC, et al. Overexpression of long non-coding RNA HOTAIR predicts poor patient prognosis and promotes tumor metastasis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134(1):121–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.03.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, et al. A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA language. Cell. 2011;146(3):353–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santarpia L, Lippman SM, El-Naggar AK. Targeting the MAPK-RAS-RAF signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(1):103–19. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.645805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Falco M, Fedele V, Cobellis L, et al. Pattern of expression of cyclin D1/CDK4 complex in human placenta during gestation. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;317(2):187–94. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0880-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Y, Arora A, Min W, et al. EdU incorporation is an alternative non-radioactive assay to [(3)H]thymidine uptake for in vitro measurement of mice T-cell proliferations. J Immunol Methods. 2009;350(1–2):29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He HJ, Zhu TN, Xie Y, et al. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate inhibits interleukin-6 signaling through impaired STAT3 activation and association with transcriptional coactivators in hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(42):31369–79. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jalali S, Bhartiya D, Lalwani MK, et al. Systematic transcriptome wide analysis of lncRNA-miRNA interactions. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e53823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li JH, Liu S, Zhou H, et al. starBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D92–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang JH, Li JH, Shao P, et al. starBase: a database for exploring microRNA-mRNA interaction maps from Argonaute CLIP-Seq and Degradome-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D202–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng JC, Klausen C, Leung PC. Hydrogen peroxide mediates EGF-induced down-regulation of E-cadherin expression via p38 MAPK and snail in human ovarian cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(8):1569–80. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiao JW, Wen F. Tanshinone IIA acts via p38 MAPK to induce apoptosis and the down-regulation of ERCC1 and lung-resistance protein in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2011;25(3):781–88. doi: 10.3892/or.2010.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ptak A, Gregoraszczuk EL. Bisphenol A induces leptin receptor expression, creating more binding sites for leptin, and activates the JAK/Stat, MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt signalling pathways in human ovarian cancer cell. Toxicol Lett. 2012;210(3):332–37. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Y, Yang J, Liao W, et al. Cytosolic FoxO1 is essential for the induction of autophagy and tumour suppressor activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(7):665–75. doi: 10.1038/ncb2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang B, Wang X, Cai F, et al. Antitumor properties of salinomycin on cisplatin-resistant human ovarian cancer cells in vitro and in vivo: involvement of p38 MAPK activation. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(4):1371–78. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W, Ren F, Wu Q, et al. MicroRNA-497 suppresses angiogenesis by targeting vascular endothelial growth factor A through the PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways in ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep. 2014;32(5):2127–33. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim HJ, Lee DW, Yim GW, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR is associated with human cervical cancer progression. Int J Oncol. 2014;46(2):521–30. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]