Abstract

Sibutramine is an anorectic that has been banned since 2010 due to cardiovascular safety issues. However, counterfeit drugs or slimming products that include sibutramine are still available in the market. It has been reported that illegal sibutramine-contained pharmaceutical products induce cardiovascular crisis. However, the mechanism underlying sibutramine-induced cardiovascular adverse effect has not been fully evaluated yet. In this study, we performed cardiovascular safety pharmacology studies of sibutramine systemically using by hERG channel inhibition, action potential duration, and telemetry assays. Sibutramine inhibited hERG channel current of HEK293 cells with an IC50 of 3.92 μM in patch clamp assay and increased the heart rate and blood pressure (76 Δbpm in heart rate and 51 ΔmmHg in blood pressure) in beagle dogs at a dose of 30 mg/kg (per oral), while it shortened action potential duration (at 10 μM and 30 μM, resulted in 15% and 29% decreases in APD50, and 9% and 17% decreases in APD90, respectively) in the Purkinje fibers of rabbits and had no effects on the QTc interval in beagle dogs. These results suggest that sibutramine has a considerable adverse effect on the cardiovascular system and may contribute to accurate drug safety regulation.

Keywords: Anorectic, Sibutramine, QT prolongation, Beagle dogs

INTRODUCTION

Sibutramine, an anti-obesity drug, is a centrally acting serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor structurally related to amphetamines (Heal et al., 1998). Sibutramine has been reported to increase cardiovascular disease potential (James et al., 2010) and has been withdrawn from the market in the United States, the European Union, and the Republic of Korea in 2010. Despite the official ban of sibutramine, illicit products containing sibutramine are available in many countries, possibly resulting in significant toxicities and even mortality (Muller et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2011; Heo and Kang, 2013). The Sibutramine Cardiovascular and Diabetes Outcome Study (SCOUT) showed that long-term treatment (for 5 years) with sibutramine (10–15 mg/day) exposed subjects with pre-existing cardiovascular disease to a significantly increased risk for nonfatal myocardial infarction and nonfatal stroke, but not cardiovascular death or all-cause mortality (James et al., 2010). However, QT prolongation, a prolonged interval from the beginning of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave of an electrocardiogram (ECG), an arrhythmia-associated effect induced by sibutramine is not well elucidated yet. In this study, we evaluated the cardiovascular safety of sibutramine with in vitro and in vivo models, which included human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) assessment using whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology techniques, action potential duration (APD) assessment using Purkinje fibers, and a telemetry study in freely moving animals (beagle dogs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and reagents

All animal procedures were approved by the committee on laboratory animal use (06141MFDS471) and performed in Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited facilities conforming to the guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals provided by the Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room at 22 ± 2°C with a 12 h light/dark cycle (light on 0800 to 2000) and were given a solid diet and tap water ad libitum. All reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise specified.

hERG assay

HEK-293 cells (CRL-1573, ATCC) were transfected with hERG cDNA (GenBank U04270, donated from the Department of Physiology, Seoul National University, Republic of Korea) with GFP cDNA in pcDNA3.1/Zeo plasmids using lipofectamine. hERG currents were recorded using a whole-cell patch clamp. Recording was performed with the Axopatch 200B amplifier and Digidata 1322A converter (Axon Instruments, USA). Recording electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass with filament (GC150 TF-7.5; Clark Electromedical Instruments, UK) on a micropuller (Narishige, Japan). The internal solution contained 130 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgATP, and 10 mM HEPES adjusted to pH 7.2. The extracellular solution was a normal tyrode solution adjusted to pH 7.4 that contained 143 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 5.0 mM HEPES, 0.33 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 16.6 mM glucose, and 1.8 mM CaCl2. The voltage step protocol (see Supplementary Fig. 1) was as follows: holding at −80 mV (resting potential), followed by an increase from −60 mV to +40 mV via 10-mV increments (step pulse, 0.1 Hz), and a step-down to −60 mV. To assess the inhibitory effect of sibutramine (sibutramine·HCl, 99.72%; LKT Laboratories, Shenzhen, China) on the hERG channel current, we measured the tail current by a single pulse protocol (−80 mV potential holding step through a 2-s +20 mV depolarization step and a 3-s −60 mV repolarization step) from visually identified GFP-positive cells (about 60% of transfection efficiency) under a fluorescence microscope (Axovision, Carl zeiss, Germany). Data from samples (n=3) were collected and analyzed with the Notocord rogram (NOTOCORD Inc., France).

APD assay

New Zealand white rabbits (male, 1.7–2.0 kg, Laboratory animal resources division, National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation) were sacrificed and Purkinje fibers of the left ventricle were placed in the normal tyrode solution and equilibrated for 2 h (O2 saturation at 37°C) at 1 Hz, 2 ms (1.5 times the threshold stimulation value). A microelectrode (20 MΩ, 3 M KCl filling) was inserted and the membrane potential was adjusted to −80 mV. Stimulus (1.3–2V, 2 ms, 1 Hz) was supplied at 37 ± 1°C through flow. After equilibration for 1 h, action potential changes induced by sibutramine treatment (20 min) were measured and analyzed with the Notocord program. Action potential duration upon 50% repolarization (APD50), action potential duration upon 90% repolarization (APD90), resting membrane potential (RMP), total amplitude (TA), and Vmax were measured 30 times immediately before treatment with a higher concentration of sibutramine, as described previously (Seop Kim et al., 2006).

Telemetry

Canis familiaris (beagle dogs, n=4, male, ∼9.0 kg, Laboratory animal resources division, National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation) underwent surgery and implantation of a transmitter (TL11M2-70-CT type, Data Science International, USA) as described previously (Kim et al., 2005). The telemetry study followed a crossover design in which four male beagle dogs were given a single oral dose of either the vehicle or one of four dose levels of sibutramine: 1, 3, 10, or 30 mg/kg. A washout period of at least 72 h was maintained between each dose and for all animals. The effects of sibutramine administration on blood pressure, heart rate, and QT interval were measured for 10 min at 1-h intervals over a 24-h period with the DataQuest software package (Data Sciences International, MN, USA) in conscious beagle dogs.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat 3.1 software (Systat Software, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test or repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test were used for multigroup comparisons.

RESULTS

hERG assay

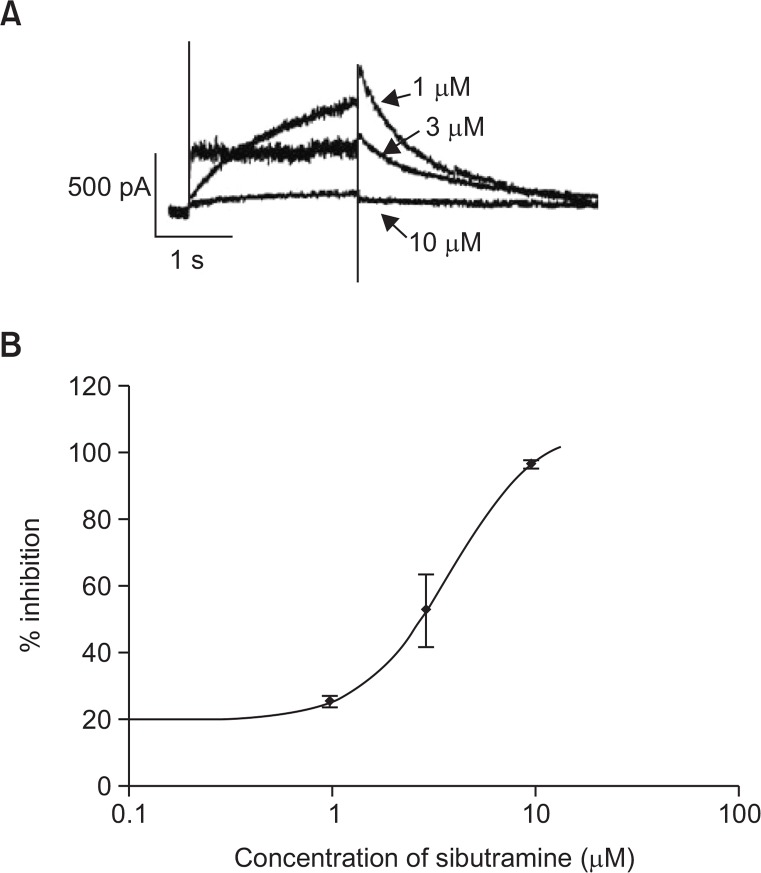

The hERG encodes the pore-forming protein KCNH2, which is thought to represent the α-subunits of the human potassium channels responsible for IKr. The most common mechanism of QT prolongation is the blockage of this ion channel. The concentration-dependent inhibition of IKr in hERG-transfected HEK293 cells by sibutramine is shown in Fig. 1. The hERG current was inhibited by 25.26 ±1.71%, 52.62 ± 10.92%, and 96.51 ± 1.38% at 1 μM, 3 μM, and 10 μM, respectively, with an IC50 of 3.92 μM (Hillslope: 1.9768).

Fig. 1.

Effect of sibutramine on hERG currents expressed in HEK 293 cells. HEK 293 cells were transfected transiently with hERG plasmid. (A) Shows representative current traces recorded in sibutramine-treated cell. (B) Shows the dose-response relationships for the hERG tail current block. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (n=3).

APD assay

In addition to the hERG assay, we performed the APD assay, which can elucidate cellular mechanisms affecting repolarization. In the left ventricular Purkinje fibers of rabbit, sibutramine decreased APD50 and APD90 at 10 μM and 30 μM without influencing the total amplitude, resting membrane potential, and Vmax (Table 1).

Table 1.

Concentration-dependent effects of sibutramine on APD recorded from rabbit Purkinje fibers

| Sibutramine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Concentration | APD50 (msec) | APD90 (msec) | RMP (mV) | Vmax (V/s) | TA (mV) |

| Control | 241.41 ± 8.65 | 311.41 ± 7.19 | −81.79 ± 2.16 | 363.55 ± 18.99 | 114.55 ± 2.50 |

| 1 μM | 233.77 ± 7.23 | 304.61 ± 6.04 | −81.39 ± 1.84 | 370.36 ± 19.66 | 115.37 ± 2.12 |

| 10 μM | 206.00 ± 3.01* | 283.61 ± 3.24* | −82.15 ± 1.89 | 367.82 ± 19.08 | 115.69 ± 0.99 |

| 30 μM | 172.20 ± 5.39** | 258.98 ± 2.34** | −78.65 ± 1.52 | 337.75 ± 22.80 | 111.92 ± 3.16 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SE (

p<0.05,

p<0.01, ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s test, n=3). RMP, resting membrane potential; Vmax, maximal upstroke velocity of phase 0; TA, total amplitude.

Telemetry

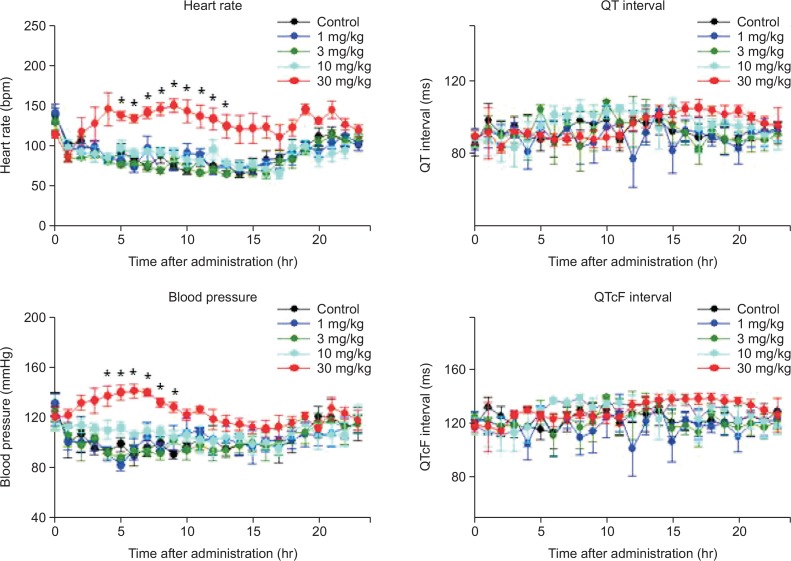

Telemetry assay was performed in freely moving animals (conscious dogs) to determine whether ventricular repolarization or associated arrhythmias occurred due to integrated effects on the full complement of ion channels and cell types. Table 2 shows the baseline cardiovascular parameters in each dog. Following oral administration of sibutramine-filled gelatin capsules to conscious dogs followed by 24-h observation, there were no significant or biologically relevant changes in lead II ECG variables (RR, PR, QRS, QT, QTcF [corrected QT interval using Fridericia’s formula; QT/RR0.33]). In contrast, the heart rate and mean blood pressure were significantly higher after administration of sibutramine (30 mg/kg) in comparison with that in the control group. In particular, the maximal effects of sibutramine on heart rate (76 Δbpm) and blood pressure (51 ΔmmHg) were observed at 9 h and 6 h after administration, respectively (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Cardiovascular parameters in each dog

| Dog 1 | Dog 2 | Dog 3 | Dog 4 | Mean ± S.E. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR-Interval (ms) | 86.24 | 88.67 | 87.49 | 90.53 | 88.23 ± 0.91 |

| QRS-Interval (ms) | 32.57 | 30.35 | 32.93 | 29.66 | 31.38 ± 0.81 |

| QT-Interval (ms) | 100.05 | 86.88 | 67.69 | 101.92 | 89.14 ± 7.89 |

| RR-Interval (ms) | 401.41 | 444.19 | 425.61 | 424.66 | 423.97 ± 8.76 |

| QTcB | 157.91 | 130.36 | 103.76 | 156.40 | 137.11 ± 12.79 |

| QTcF | 135.22 | 113.56 | 89.73 | 135.21 | 118.43 ± 10.84 |

| Core Temperature (°C) | 37.62 | 37.39 | 35.55 | 36.76 | 36.83 ± 0.46 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 91.55 | 83.14 | 80.39 | 92.69 | 86.94 ± 3.05 |

| Mean Pressure (mmHg) | 99.41 | 88.68 | 91.38 | 108.70 | 97.04 ± 4.50 |

Baseline values of ECG interval, hemodynamic parameters and core body temperature of normal freely moving beagles dogs by remote radiotelemetry (QTcB: Bazett’s correction; QT/(RR/1000)0.5, QTcF: Fridericia’s correction; QT/ (RR/1000)0.33).

Fig. 2.

Effect of sibutramine on cardiovascular parameters in beagle dogs. The telemetry monitoring was performed following oral administration of sibutramine (1, 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg) in conscious beagle dogs. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (*p<0.05 vs. control, repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test, n=4).

DISCUSSION

Sibutramine was reported to induce mania, panic attacks, and psychosis (Perrio et al., 2007). Furthermore, sibutramine was withdrawn from the U.S market and also from the EU and the Republic of Korea due to the risk of serious cardiovascular events. Recent studies reported that sibutramine present in counterfeit drugs and dietary supplements contributes to a safety issue; however, the association of QT prolongation with sibutramine is not clearly understood yet. We evaluated the possible mechanism underlying sibutramine-induced cardiovascular adverse effect. We demonstrated that sibutramine inhibited hERG potassium channels in an in vitro test system, while the APD assay in Purkinje fibers of rabbit showed that sibutramine induced a decrease in APD50 and APD90. These results are consistent with previous report that showed APD shortening induced by sibutramine in guinea pig papillary muscle (Kim et al., 2008). It is not surprised because a cardiac action potential is composed of different phases that are produced by the currents of Na+, Ca2+, and K+. We presumed that sibutramine has a weak QT prolongation and APD shortening effect due to mixed ion channel effects. In addition, the in vivo telemetry experiments revealed that an acute sibutramine administration may not have effects on QT prolongation. However, sibutramine, at 30 mg/kg, increased the heart rate and mean blood pressure in beagle dogs. Sibutramine is known to have a peripheral sympathomimetic effect, consequently this may affect hemodynamic parameters. In fact, a shortened APD may contribute to the changes of heart rate and blood pressure in beagle dogs, because APD and the refractory period decrease is essential for increase in the heart rate. Additional in vivo models that are designed to study possible risk factors (e.g. chronic administration and electrolyte imbalance) could be considered that might better reveal the basis of QT prolongation. In summary, our results suggest that sibutramine is associated with cardiovascular risks reported previously (Scheen, 2010), even though we could not establish a causal relationship between QT prolongation and sibutramine. Furthermore, these results may contribute to the regulatory response to sibutramine safety issues.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by 06141MFDS471 of Ministry of Food and Drug Safety of Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Heal DJ, Aspley S, Prow MR, Jackson HC, Martin KF, Cheetham SC. Sibutramine: a novel anti-obesity drug. A review of the pharmacological evidence to differentiate it from d-amphetamine and d-fenfluramine. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:S18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo SH, Kang MH. A case of dilated cardiomyopathy with massive left ventricular thrombus after use of a sibutramine-containing slimming product. Korean Circ J. 2013;43:632–635. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2013.43.9.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James WP, Caterson ID, Coutinho W, Finer N, Van Gaal LF, Maggioni AP, Torp-Pedersen C, Sharma AM, Shepherd GM, Rode RA, Renz CL, Investigators S. Effect of sibutramine on cardiovascular outcomes in overweight and obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:905–917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Seo JW, Hwang JY, Han SS. Effects of combined treatment with sildenafil and itraconazole on the cardiovascular system in telemetered conscious dogs. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2005;28:177–186. doi: 10.1081/DCT-52525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KS, Park SJ, Lee HA, Kim DK, Kim EJ. Electrophysiological safety of sibutramine HCl. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2008;27:553–558. doi: 10.1177/0960327108095991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Weinmann W, Hermanns-Clausen M. Chinese slimming capsules containing sibutramine sold over the Internet: a case series. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:218–222. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrio MJ, Wilton LV, Shakir SA. The safety profiles of orlistat and sibutramine: results of prescription-event monitoring studies in England. Obesity. 2007;15:2712–2722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheen AJ. Cardiovascular risk-benefit profile of sibutramine. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs. 2010;10:321–334. doi: 10.2165/11584800-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seop Kim D, Kim KS, Hwan Choi K, Na H, Kim JI, Shin WH, Kim EJ. Electrophysiological safety of novel fluoroquinolone antibiotic agents gemifloxacin and balofloxacin. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2006;29:303–312. doi: 10.1080/01480540600652996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MH, Chen SP, Ng SW, Chan AY, Mak TW. Case series on a diversity of illicit weight-reducing agents: from the well known to the unexpected. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:250–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.