Abstract

Signal transduction pathways interact at various levels in defining tissue morphology, size and differentiation during development. Understanding of the mechanisms by which these pathways collude has been greatly enhanced by recent insights into how shared components are independently regulated and how the activity of one system is contextualized by others. Traditionally, the components of signalling pathways have been assumed to show pathway fidelity and to act with a high degree of autonomy. However, as illustrated by the Wnt and Hippo pathways, there is increasing evidence that components are often shared between multiple pathways and other components talk to each other through multiple mechanisms.

Introduction

Traditionally, the components of signaling pathways have been assumed to show pathway fidelity and to act with a high degree of autonomy. A classical example is the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase pathway. This signaling system has a core set of molecules that couple production of cAMP to activation of protein kinase A (PKA) and regulation of downstream targets. In some cases this is linear and relatively insulated – such as the adrenaline-induced effects of PKA activation of phosphorylase kinase leading to glycogen mobilization in muscle (reviewed in Ref. 1). More commonly, however, these pathways are convoluted and subject to tiered or nested levels of input from other pathways.

Indeed, nature has placed enormous responsibility on relatively few proteins that, together, form the regulatory skeleton of cellular control. There are only a handful of primary signaling pathways that act as guide-wires in orchestrating appropriate cellular responses to external and internal cues - in stark contrast to the many thousands of proteins and processes they must control. While there is a diverse array of receptor proteins that sense specific ligands, their function is collapsed by the limited numbers of intracellular pathways to which they can couple. Moreover, many pathways contain common components further limiting their apparent potential for specificity. The obvious question, then, is how might the complexity of a cell be coordinated by such a limited vocabulary of commands? A large part of the answer emerges from the multiple ways by which these systems interact, cross-regulate, insulate and collaborate. In this review, we use the canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathway and the Hippo growth pathway to exemplify how better precision, specificity and coordination can be derived from a minimalistic parts list. We focus on these pathways as they provide examples of several emerging principles of signaling including use of common components, discrimination of signals and mechanisms for signaling coordination and integration. These pathways have been the subject of intense investigation by many laboratories over the past decade, and it is thus impossible to adequately review the literature for all of these pathways in the current review. Therefore, we refer the interested reader to a number of relevant reviews for each pathway (e.g. 2–5), and, here, will focus on advances in the past two years, as well as on a few seminal papers that highlight the crosstalk and insulation of these signaling cascades. We also note that much pathway integration occurs at the level of gene regulation through the assembly and disassembly of transcriptional complexes. This topic warrants its own treatise and we regret that it is only referred to superficially here.

The convoluted world of Wnt signaling

The Wnt pathway first emerged from elegant classical genetics in Drosophila as a key determinant for segmental and spatial organization of the body plan. These studies revealed the fundamental architecture of this pathway with double-negative regulation and feedback controls (see below; reviewed in Ref. 6). Geneticists were also the first to realize that the pathway bifurcated, with one collection of components acting on transcriptional regulation through stabilization of the transcriptional activator β-catenin and the other on aspects of planar polarity. Each arm of the pathway shared some components with the other, but certain mutations in these shared components had selective effects on one arm or the other, indicating dual and distinct roles. Moreover, some components of each arm have the rather disturbing property of lending their weight to quite distinct signaling pathways thereby raising issues of selectivity and specificity. Indeed, this trick of nature has led to significant confusion with many researchers assuming that the commonality of a component between two systems translates into that component acting as a functional link. Usually, this is not the case but it raises the question of why nature evolved pathways to employ shared gene products, given the importance of regulatory pathways. Is it simply parsimony or does this structure offer unappreciated benefits? Here, we argue the latter, while admitting the evidence for this position remains sparse.

Confusing Wnt terminology

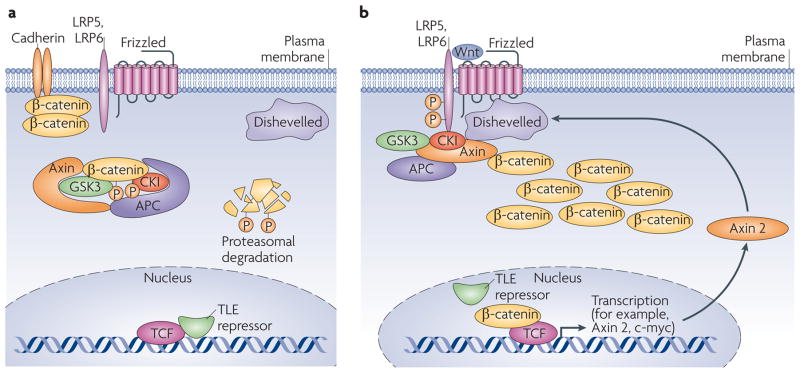

There are distinct branches Wnt signaling, commonly referred to as canonical and non-canonical pathways (Figure 1 and 2). The former largely acts through controlling levels of the non-cadherin-associated pool of β-catenin, the latter refers to other actions of Wnt that are β-catenin independent. Setting aside the literal inappropriateness of the term (‘canonical’ is defined as ‘according to recognized rules or scientific laws’), this separation of functions has been useful in simplifying analysis of Wnt biology. For example, Wnt ligands can be classified into acting canonically or non-canonically by whether they induce secondary axis formation upon injection into Xenopus embryos. Conventional descriptions of canonical Wnt signaling imply that the pathway is relatively linear - although evidence of more complex interactions has been widely appreciated through proteomic analyses 7, 8. Adherent cells contain relatively large amounts of β-catenin with the vast majority of this lining the plasma membrane in association with cadherin family cell adhesion molecules. In the absence of a Wnt signal, a complex of proteins comprising adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), a scaffolding protein termed Axin1 that acts to cluster the components, glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), casein kinase-1 (CK1) and others, acts as a machine to capture ‘surplus’ β-catenin molecules that are not cadherin-bound and to tag these by phosphorylation for ubiquitinylation and destruction via the 26S proteasome (Figure 1A). This ‘destruction complex’ is highly efficient and soluble β-catenin levels are maintained at very low levels, despite continuous synthesis of β-catenin by the cell.

Figure 1. Canonical Wnt signaling pathway.

(a) In the absence of a signal, the destruction complex (APC–Axin–GSK-3–CK1) binds and phosphorylates non-cadherin-associated β-catenin, targeting it for destruction by the proteasome. Within the nucleus, TCF/Lef1 DNA-binding proteins are bound by transcriptional repressors (TLE/Groucho). (b) The binding of Wnt ligand to its Frizzled receptor and LRP5/6 co-receptor induces a change in conformation that results in phosphorylation of the co-receptor, which creates a high-affinity binding site for Axin, causing disruption of the destruction complex. This allows β-catenin to accumulate, associate with the TCF/Lef1 proteins, dislodging the TLE repressors and hence promoting transcriptional activation of a program of genes including those encoding c-Myc and Axin2. The latter protein feeds back to inhibit the pathway by promoting assembly of more destruction complexes.

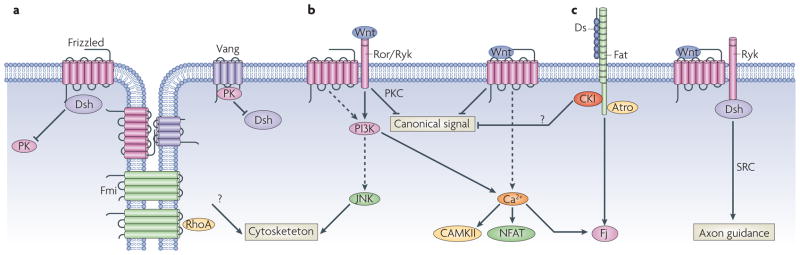

Figure 2. Non-canonical Frizzled/PCP signaling.

A large number of non-canonical Wnt/PCP signaling pathways have been described. Outlined is a vastly simplified schema highlighting some of the key players. (a) Frizzled-PCP pathway is enriched asymmetrically at cell boundaries. In Drosophila wings Frizzled (Fz), Dishevelled (Dvl) and Diego accumulate at the distal edge of each cells, and Van Gogh (Vang) and Prickle (Pk) accumulate on the proximal side of each cells. These complexes may be bridged by Flamingo-Flamingo (Fmi-Fmi) interactions across cells, as well as interactions between Fmi and Vang and Fmi and Fz and Fz and Vang. In addition there are mutually repressive interactions within the cell between distal and proximal complexes. Genetically RhoA has been placed downstream of the Frizzled-PCP complex. (b) Wnt5a functions primarily as a non-canonical Wnt ligand, acting through the tyrosine kinases Ror or Ryk. Activation of JNK, increases in intracellular calcium, leading to activation of NFAT and inhibition of canonical signaling are some of the alterations seen upon Wnt5a stimulation. (c) Non-canonical Wnts also may function through a subset of Frizzled that bias towards PCP signaling, such as Frizzled7. (d) Dachsous binding to Fat pathway regulates PCP, possibly via recruitment of Casein Kinase I (CKIε), which has been shown in different situations to inhibit or stimulate (not shown) PCP signaling. Fat also recruits the transcriptional co-repressor Atrophin, which suppresses transcription of the PCP effector gene four-jointed (Fj). (e) The atypical tyrosine kinase Ryk is another alternate Wnt receptor, which has been shown to function via Src in axon guidance.

Binding of specific Wnt ligands (of which there are 19) to specific Frizzled serpentine receptors and low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) co-receptors (typically LRP5 or LRP6), acts through a protein termed Dishevelled (Dvl) to switch off the destruction complex by stopping phosphorylation of β-catenin (Figure 1B). Newly synthesized, unphosphorylated β-catenin, freed from its otherwise imminent fate of destruction, begins to accumulate and to associate with members of a family of DNA-binding proteins, the TCF/LEF family. Together, these complexes act to induce expression of a cohort of genes including c-myc that influence proliferation and apoptosis (reviewed in Ref. 9).

The canonical pathway acts in a manner akin to a stationary car in which the accelerator is depressed but the handbrake is also engaged, resulting in no net movement, albeit at the expense of energy. Wnt ligands have no effect on the accelerator, but act by relieving the brake. One of the target genes induced in response to Wnt is Axin2 which encodes a protein related to the Axin1 scaffold 10. Axin1 is the least abundant molecule in the destruction complex and sets the limit on the numbers of such complexes in a cell 11, although modulation of APC levels can also affect the capacity of the pathway 12. Induction of the Axin2 gene therefore results in increases in the capacity of a cell to process β-catenin for degradation, turning down the pathway. This feedback loop causes an inherent limit to the duration of Wnt signaling. Mutations associated with various cancers (including the majority of colorectal cancers) inactivate components of the destruction complex (APC, Axin) or remove the sites of phosphorylation on β-catenin, effectively cutting the brake line (reviewed in Ref. 13). Indeed, levels of β-catenin in such tumours are often far higher than observed during natural activation of the pathway, indicating the effectiveness of the restraints imposed on β-catenin.

Redirection rather than inhibition

Treatment of cells with inhibitors of GSK-3 results in activation of the canonical pathway, as does genetic inactivation of this protein kinase - as long as both mammalian GSK-3 genes (α and β) are silenced 14. Genetic inactivation of 3 of the 4 GSK-3 alleles does not result in constitutive Wnt pathway activation. This is because only a small fraction of the available GSK-3 molecules (~5%) is physically associated with the destruction complex. Hence, even with only 25% residual GSK-3 in a cell, this kinase saturates the even lower concentration of the available destruction complex (dictated by Axin levels11). Only the GSK-3 molecules bound to the complex are relevant for Wnt signaling, and this represents one mechanism that leads to signal insulation (see below). Since inhibition of GSK-3 induces canonical signaling and Wnt inactivates the destruction complex, then, ipso facto, Wnt must inactivate GSK-3. This supposition is also consonant with the means by which GSK-3 is regulated by other pathways such as mitogens and growth factors that act through phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase or cAMP. These pathways induce phosphorylation of serine residues, Ser21 and Ser9 on the N-terminal domains of GSK-3α and β, respectively, which reduces activity of the kinase 15.

However, several groups have shown that Wnt disengages the destruction complex not through inactivation of its components, but through a “bait-and-switch”-like mechanism 14. Binding of Wnt to the Frizzled–LRP5/6 receptor complex induces a conformational change in LRP5/6 such that it becomes an attractive substrate for GSK-3 and CK1 16, 17. Phosphorylation of the co-receptor by these kinases creates a high-affinity binding site for Axin and this leads to dissolution of the destruction complex, although the precise mechanism remains unclear 18. Therefore, Wnt increases LRP5/6 phosphorylation by GSK-3 and CK1, which leads to lower β-catenin phosphorylation. Importantly, Wnt signaling does not change the activity state of these two protein kinases, rather it redirects their attention to a distinct substrate(s) (LRP5/6). A dual role in Wnt signaling has also been proposed for APC in Drosophila in which the this tumour suppressor not only promotes β-catenin processing in the absence of a Wnt signal but, in the presence of Wnt, stimulates Axin degradation, hence accelerating the signal 19.

Insulating the wiring

The proteins that comprise the canonical Wnt pathway are remarkable in that several also play important roles in other cellular functions (e.g. β-catenin’s dual role in cell adhesion and signaling, APC’s dual role in protein degradation and microtubule organization, the pleiotropic nature of GSK-3 and CK1, etc.). Teleologically, it makes little sense for such an essential and influential pathway to be comprised of elements that appear to be borrowed from the inventory of other cellular processes. There are important questions raised by this organizational strategy. Firstly, are there are effective mechanisms to insulate the shared components such that the cell can maintain signal discrimination? If so, are there advantages in such organization as compared with having entirely distinct molecules for each pathway? As described for GSK-3 above, only the small fraction of molecules of GSK-3 that are physically associated with the destruction complex are relevant to Wnt signaling. There is a considerable literature associating, for example, polypeptide growth factor-induced inactivation of GSK-3 via N-terminal domain (Ser 21/9) phosphorylation with direct activation of the Wnt pathway - as judged by β-catenin stabilization. Despite this literature, cellular stimuli that lead to inhibition of GSK-3 through N-terminal domain phosphorylation (e.g. mitogens that activate Akt/PKB) do not cause stabilization of β-catenin. Moreover mutants of GSK-3 that cannot be inactivated by N-terminal domain phosphorylation are fully competent in mediating Wnt activation of β-catenin 14, 20, 21. These findings indicate that the small number of GSK-3 molecules bound to Axin are insulated from the bulk of the protein kinase that is not associated with the destruction complex. The isolation mechanisms responsible for this signaling selectivity is not completely understood. However, Axin acts to chaperone both β-catenin and GSK-3, rendering the phosphorylation reaction, in essence, first-order, reducing sensitivity to the specific activity of GSK-3. Hence, even if the Axin-associated GSK-3 is partially inactivated by phosphorylation of its N-terminal domain, the effect on β-catenin phosphorylation will be marginal and it will not accumulate. It is also possible participation in the destruction complex physically shields GSK-3 from the protein kinases that phosphorylate and inactivate the majority of the enzyme not associated with the complex.

There is also genetic evidence in Drosophila that the dual roles of β-catenin in cell adhesion and nuclear signaling are insulated. Certain Armadillo mutants have been isolated that affect only cell adhesion or transcriptional properties (as assessed by tissue integrity and segmental polarity defects) 22. The advantages of this duality of protein functions may relate to higher order coordination, a possibility we will return to below.

Non-canonical Wnt signaling

Despite the evident complexities, the canonical Wnt pathway is still far better understood than the “non-canonical” Wnt pathway (Figure 2). Originally the non-canonical Wnt pathway was synonymous for the planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway - a pathway that regulates tissue morphogenesis and the synchronous polarity of sheets of cells (reviewed in Ref. 23). This was based on the discovery in Drosophila that mutations in Frizzled and Disheveled, as well as the other “core PCP genes” (Van Gogh, Flamingo, Diego and Prickle) disrupt tissue organization in a β-catenin (Armadillo)-independent manner. Given the presence of Frizzled and Disheveled in the PCP pathway, it was long thought that a non-canonical Wnt would activate Frizzled to provide spatial information to the PCP pathway. However, extensive genetic analysis failed to identify any PCP function for the Drosophila Wnt ligands. Loss of all five of the Wnt ligands expressed in the wing 24, and removal of most Wnt ligands in the abdomen failed to disrupt their PCP 25, showing that Wnt ligands do not control PCP in these tissues. Therefore, rather than calling Frizzled-mediated PCP signalling the “non-canonical Wnt pathway”, it is probably more appropriate to refer to it as the Frizzled-PCP pathway.

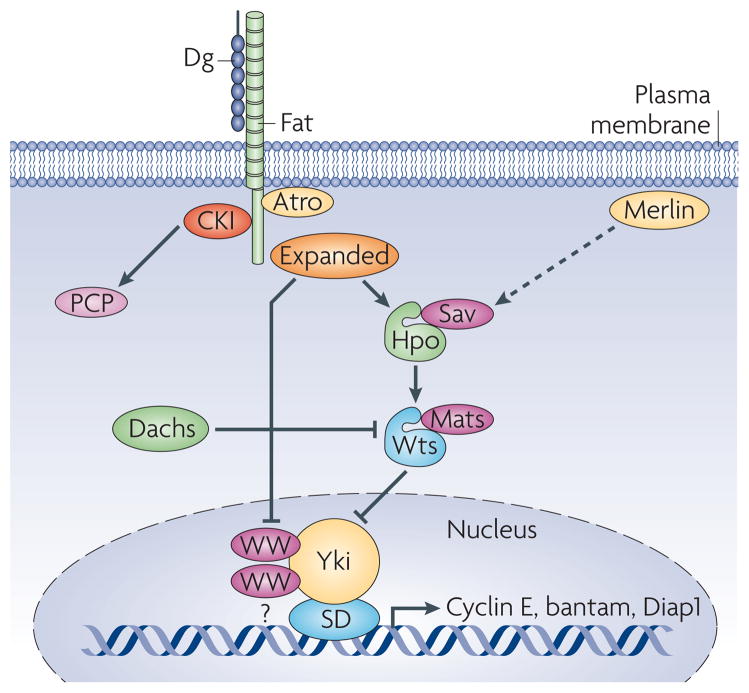

A search for alternative upstream regulators of the Frizzled-PCP pathway in Drosophila identified Fat and Dachsous as an important group of PCP regulators in all tissues (Figures 2 and 3). Fat and Dachsous are large atypical cadherins that control PCP in flies and in mammals 26–29. In flies, Fat and Dachsous also function in growth regulation. While these large cadherins were first proposed to act upstream of the Frizzled core PCP genes 28, more recent studies have suggested that they are in fact in a parallel pathway for PCP control (30 and reviewed in Ref. 31). Current models suggest that Dachsous binds to Fat to inhibit its activity. The cytoplasmic domain of Fat binds a transcriptional co-repressor, Atrophin 32, which regulates PCP target genes, such as four-jointed. Fat activity is controlled by gradients of expression of Dachsous and Four-jointed 33, 34. How Fat activity then regulates tissue organization is still unclear.

Figure 3. The Fat growth and PCP pathway.

The large cadherin Dachsous (Ds) acts as an inhibitory ligand for the large cadherin Fat. Fat functions to regulate planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling by recruiting the transcriptional co-repressor Atrophin (Atro). Atrophin represses the transcription of the PCP gene four-jointed. It is unclear at present the identity of the transcription factor Atro binds to regulate four-jointed transcription. Fat also regulates growth via control of the Hippo kinase (Hpo) pathway. Current models suggest that Fat regulates Hpo activity either through the FERM domain protein Expanded or the small myosin-like protein Dachs. Dachs has been shown to regulate the stability of Wts Wts phosphorylates Yki, leading to its export from the nucleus. In the absence of Fat or the other Hpo components, Yki promotes the transcription of Cyclin E, the micro RNA bantam and the anti-apoptotic gene Diap1. Sav and Mats are adaptor proteins essential for Hpo and Wts activity. Merlin (Mer) is another FERM domain protein that functions in parallel to Expanded in controlling activity of the Hippo pathway.

The Frizzled-PCP and Fat-Dachsous pathways are both conserved in vertebrates, where they function to regulate tissue organization, most notably the polarized movements of convergent extension during development, as well as the orientation of hair cells in the inner ear, and neural tube closure (reviewed in Ref. 35). In a surprising twist, loss of function of a number of Wnt ligands, which are largely “non-canonical Wnt ligands ”, give rise to similar PCP phenotypes in vertebrates. This has led to the proposal that some Wnts may function in a vertebrate non-canonical Wnt PCP pathway. It is still unclear how the non-canonical Wnt PCP pathways relate to the “core PCP” pathway or the Fat-Dachsous PCP cassette.

Wnt ligands have been traditionally subdivided into canonical and non-canonical groups, based on their ability to induce a secondary body axis in Xenopus and to transform C57MG epithelial cells reflecting β-catenin signalling 36, 37. Wnt1, Wnt-3a and Wnt-8 thus have been suggested to act through the canonical pathway (i.e. β-catenin), while Wnt 5a, Wnt-4 and Wnt-11 have been classed as non-canonical Wnt ligands, not affecting β-catenin levels, but causing convergent extension movements during development. A plethora of downstream mediators respond to these non-canonical Wnt ligands (reviewed in Ref. 38), suggesting that there are in fact multiple non-canonical Wnt pathways. One class of downstream mediators have been called the Wnt-Ca2+ pathway, and are associated with activation of phospholipase C (PLC) increased intracellular calcium levels, activation of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-II (CaMKII), protein kinase C (PKC) and the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) transcription factor. Another set of responses involves the small G proteins Rac, Rho and Rap, and is associated with activation of the Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway and alterations in the cytoskeleton. However, the boundaries between these classes are still unclear, and need further clarification. A larger question that is still unanswered is why Wnts are generally accepted to regulate PCP in vertebrates, yet careful genetic analysis in Drosophila has excluded a role for Wnts in PCP. One possibility, of course, is that the use of Wnts in PCP is a vertebrate-specific adaptation. However an alternative possibility is that role of Wnts in PCP in higher organisms may also be indirect, as has been shown in Drosophila, where Wg regulates the expression of PCP regulators such as Dachsous and Four-jointed. In any case, more studies are needed to define the exact role of the “non-canonical” Wnts in PCP.

Crosstalk between various Wnt pathways

A notable characteristic of many forms of non-canonical Wnt signaling appears to be an inhibition of canonical signaling. Early studies showed that overexpressed Wnt5a can block the stabilization of β-catenin induced by Wnt-1 39. Expression of Wnt5a can also activate a nemo-like kinase (NLK) that phosphorylates TCF transcription factors, thus inhibiting canonical Wnt signaling 40, 41. In fact, it appears that simply inhibiting canonical signaling can, in some conditions, lead to PCP effects. For example, overexpression of the canonical Wnt feedback inhibitor, the cytoplasmic EF hand protein Naked, produces strong PCP effects in the fly 42 and convergent extension defects in frogs 43.

Recent work has identified additional pathways mediating cross-talk between the non-canonical Wnt pathway and the canonical one. Lee and coworkers 44, 45 found that stimulation of Wnt5a lead to increased PKC activity. Activated PKC phosphorylates RORα (retinoic acid-related orphan nuclear receptor α). Phosphorylated RORα binds with high affinity to β-catenin at promoters and represses transcription, thus inhibiting β-catenin dependent activity. This obviously opens up many avenues for modifying β-catenin activity, through the many pathways that can activate PKC. In yet another mechanism for cross-talk between canonical and non-canonical Wnts, Sato et al. 46 have recently shown that Wnt5a can also suppress canonical Wnt signaling via competition for Frizzled receptors and also by inducing internalization of Frizzled2. Recently, Wnt5a has been shown to employ both Dishevelled and APC to modulate its effects on focal adhesion dynamics during cell movement 47. APC has long been recognized to play important roles in microtubule organization and dynamics 48. This provides an apt example of how the lines between the canonical and non-canonical elements can be blurred.

There is still a great deal of debate as to how non-canonical Wnt ligands function. For example, Wnt5a has been variously shown to regulate Ca2+, Rac, Src kinases, CaMKII, JNK and β-catenin 44–46, 49–52. Part of the answer to this complexity may lie in the cellular context and the specific Frizzled receptors these cells express. For example, while Wnt5a is needed for convergent extension processes in embryonic development, in a β-catenin-independent manner, co-expression of Frizzled4 and LRP5 can convert the Wnt5a response to stabilizing β-catenin, as can expression of Frizzled5 52, 53.

Non-Frizzled Wnt receptors

While it is clear that some of the diversity of Wnt signaling can be explained by the Frizzled receptor complement present on different cells, excitingly, recent data has suggested that some of the answer may also lie in newly described non-Frizzled receptors for some Wnt ligands, the Ryk and Ror tyrosine kinases (51, reviewed in Refs 38, 45, 54 )

The tyrosine kinases Ror and Ryk have been shown to function as Wnt receptors in a variety of systems. Ror has a CRD domain, similar to that of Frizzled, and Wnt5a binds to the CRD domain of Ror2 with high affinity 52. Overexpressed Ror2 leads to convergent extension defects, suggesting it functions in a PCP pathway like Wnt5a 51, Addition of Wnt5a to purified Ror2 52 can inhibit or activate β-catenin signaling, depending on the co-receptor context. Aside from the presence or absence of Ryk and Ror2, other factors can bias Wnt5a to act through a canonical or non-canonical response. For example, a secreted collagen protein, Cthrc1, can potentiate the Wnt-Ror2-Fz interaction, enhancing PCP signaling of Wnt5a 55. Conversely, there are also non-Wnt ligands for the Frizzled receptors, such as Norrin56, that can activate the canonical pathway. This exciting finding raises the question if there are many other, as yet unidentified, ligands that can impact on the selection of the canonical and non-canonical pathways.

Growth control by Fat PCP regulators

Surprisingly, the large cadherins Fat and Dachsous are not dedicated solely to the control of PCP but have another, apparently independent, existence as important growth regulators. Loss of fat leads to dramatic tissue overgrowth, leading to its original classification as a “Drosophila tumour suppressor gene”. Subsequently, genetic studies indicated that fat regulates growth through a conserved kinase cassette, known as the Hippo kinase pathway (reviewed in Ref. 31).

The Hippo pathway was first discovered and characterized in Drosophila (reviewed in Ref. 57). The core of the Hippo pathway is relatively simple (Figure 4) and well conserved in vertebrates. The Sterile 20-like kinase Hippo (Hpo) forms a complex with the WW-repeat scaffolding protein Salvador (Sav) to phosphorylate and activate the DBF family kinase Warts (Wts). Activated Wts, in association with adaptor protein Mats (‘mob as tumor-suppressor’) phosphorylates and inhibits Yorkie (Yki), a transcriptional coactivator. Yki is a non-DNA binding coactivator, which enhances transcription of genes that promote cell proliferation (such as cyclin E and the microRNA bantam) and prevent apoptosis (the Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis 1 (diap-1)). The phosphorylation of Yki by Wts inhibits Yki nuclear localization, preventing it from acting on its growth-promoting and apoptosis-inhibiting targets. Yorkie functions with the transcription factor Scalloped in the regulation of growth control 58–60.

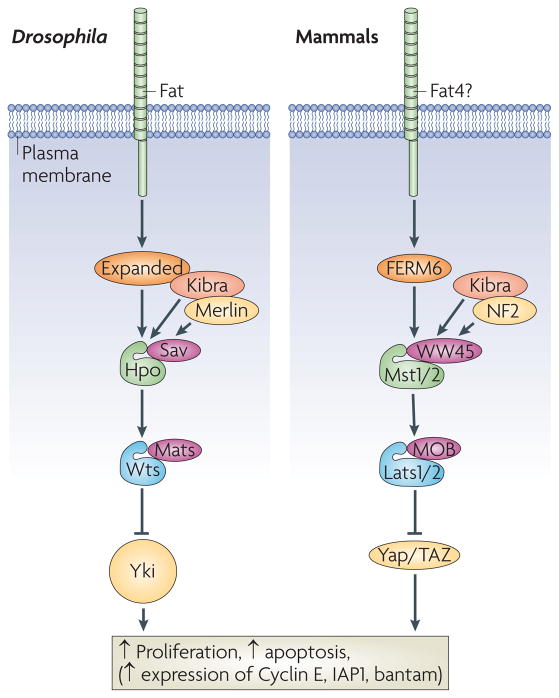

Figure 4. The core Hippo pathway.

The core Hippo pathway was defined in Drosophila as a cassette composed of the Ste20 family kinase Hippo (Hpo), which forms a complex with the WW domain adaptor protein Salvador (Sav). Hpo phosphorylates and activates the NDR family kinase Warts (Wts), which is complexed with the adaptor protein MATS (‘Mob as Tumour Suppressor’). Wts phosphorylates the transcriptional co-activator Yorkie (Yki). Phosphorylated Yki is bound by 14-3-3 proteins and excluded from the nucleus. When in the nucleus, Yki promotes the transcription of growth-promoting and apoptosis-inhibiting genes, such as Cyclin E and Diap1. Upstream of Hpo lies the cadherin Fat, and the FERM domain proteins Expanded (Ex) and Merlin. Kibra is a WW domain protein that promotes Ex-Mer interactions, and enhances Hpo pathway activity. The analogous pathway in mammals is outlined on the right. YAP and TAZ are homologous to Yorkie, Mst1/2 are homologous to Hpo, Lats1/2 are homologous to Wts, Sav is homologous to WW45, NF2 is homologous to Merlin and FRMD6 is homologous to Ex. The vertebrate homolog of Fat is Fat4, but this protein has not yet been shown to function in the vertebrate Hippo pathway.

Genetic studies clearly indicate that Fat regulates the Hippo pathway 31, 61–64, but these and other studies also suggest that there are other, as yet unidentified cell surface receptors 65–67. How the Hippo pathway connects to the Fat and Dachsous cadherins and other cell surface receptors is still unclear and is a point of much current research. Some studies suggest that Fat regulates Hippo activity via the FERM domain protein Expanded, which functions redundantly with another FERM domain protein Merlin/NF2 to control Hippo activity 68. Transcription of fat, dachsous, four-jointed, expanded and merlin are enhanced by loss of Hippo pathway activity, providing negative feedback, and also allowing changes in Hippo activity to be transmitted to adjacent cells. Fat also binds Casein Kinase Iε, which promotes Hpo pathway activity 69, 70. There are multiple interactions between the upstream components. Expanded can bind Hpo, and Merlin can bind Sav71. Interactions between Expanded and Merlin are promoted by Kibra, a cytoplasmic protein with two WW domains and a C2 domain that is essential for maximal Hippo pathway activation 71–73. In addition, Kibra can bind Hpo, promoting its association with membranes, which may contribute to activation of the pathway. Expanded can also regulate Yki in a Hpo independent manner, sequestering Yki at apical junctions 57,74. The small myosin protein Dachs also functions downstream of Fat to modulate Hippo pathway activity, possibly via control of the stability of Wts 62. More work is clearly needed to understand how Fat and other cell surface receptors regulate growth via the Hippo pathway.

Study of Hippo pathway components in vertebrates revealed conservation of the general organization observed in Drosophila, though as is often the case, multiple family members appear in the vertebrate pathway (reviewed in Ref. 57). The vertebrate orthologs of Hippo are Mst1 and Mst2. Like Hippo, Mst1 and Mst2 phosphorylate and activate the Wts orthologs, Lats1 and Lats2. Lats1 and Lats2 phosphorylate the two Yorkie homologues, YAP and TAZ, leading to the cytoplasmic retention of these growth-promoting transcriptional co-activators. YAP and TAZ partner with four TEAD transcription factors (TEAD1-4), as well as Runx, ErbB-4 and p73. Interestingly, loss of Mst1 and Mst2, WW45 and Lats1 and Lats2, as well as amplification of YAP, are involved in a variety of cancers. In addition, the long-studied, but poorly understood phenomena of contact inhibition was demonstrated to require YAP and the Hippo pathway. There are four Fat-like genes in mammals, but it is not yet known if they regulate Hippo activity, or if there are other regulators in higher organisms.

Bountiful crosstalk in the Hippo pathway

As we learn more about the Hippo pathway, the initially simple, linear pathway described from genetic studies begins to unravel into a much more complicated and intertwined picture, revealing many points of cross-talk with multiple signaling pathways (Figure 5). Work in Drosophila has shown that Wg and Dpp regulate expression of Dachsous and Four-jointed 28, 75, suggesting that activity of the Wg and Dpp may impact Hippo signaling. Conversely, expression of Wg and Serrate (a Notch ligand), are regulated by Yki 62. Yki also regulates diverse morphogen signaling by controlling expression of the heparan sulfate proteoglycans Dally and Dally-like 76. Interestingly, the microRNA bantam is not only regulated by the Hippo pathway, but also by Notch, Wg and insulin/TOR signaling77. The complexity of bantam control also highlights differential transcription factor interactions with Yorkie in growth control. While the TEAD family transcription factor Scalloped functions with Yorkie to regulate growth in the wing, recent studies have shown that the TALE family transcription factor Homothorax, together with the Zn finger transcription factor Teashirt, function with Yorkie to regulate growth in the fly eye disc 78.

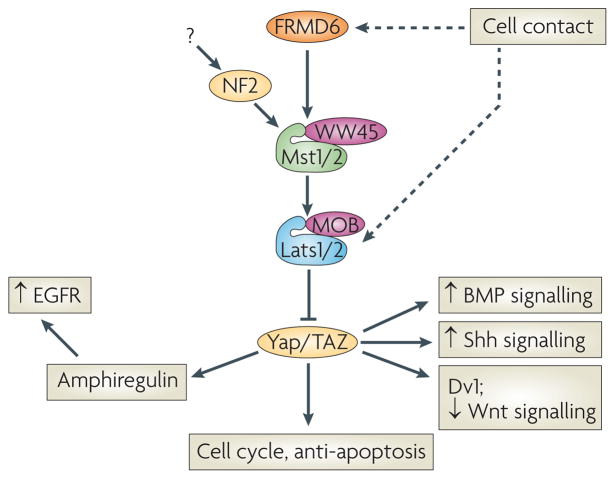

Figure 5. Crosstalk in the Hippo pathway.

Recent studies have uncovered unsuspected cross-talk between the Hippo pathway and other growth regulators. Cell contact is still detected in MEFs lacking both Mts1 and Mts2, indicating an Mst-independent input (possibly a kinase) that can phosphorylate and activate Lats1 and Lats2. Lats1/2 then inhibits YAP/TAZ to control growth. YAP can function as a transcriptional co-activator of SMADs, enhancing BMP signaling. YAP also can stimulate Gli transcription, enhancing Shh signaling. AKT can inhibit Mst1 kinase, providing another avenue for growth promotion and anti-apoptotic activity of PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. TAZ can bind Dishevelled (Dvl), inhibiting β-catenin signaling in the cytoplasm. When TAZ translocates to the nucleus, it frees Dvl to activate β-catenin, enhancing Wnt signaling. Nuclear YAP also regulates the expression of Amphiregulin, an EGFR ligand. Therefore loss of Mst or Lats in one cell can drive proliferation in that cell, while simultaneously activating the proliferation of nearby cells via the EGFR pathway.

Although the transcriptional co-activator YAP was thought to be committed to the Hippo pathway, a number of exciting studies have uncovered roles for YAP in regulating the signaling strength of a number of other well-characterized signaling pathways. A recent study revealed that YAP can act as a transcriptional activator in the bone morphogenic protein (BMP) pathway with Smad1, and is needed for BMP suppression of neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells 79. Therefore when Hippo pathway activity is high, YAP is phosphorylated and excluded from the nucleus, reducing activity of the BMP pathway. This provides integration of Hippo and BMP signaling at the transcriptional level. This integration is conserved, as in Drosophila, Yorkie is needed for maximal signaling by the BMP ortholog Decapentaplegic (Dpp)79. Recent studies have revealed that YAP also provides an integration point in Hedgehog signaling 80, acting as a transcriptional co-activator for Gli transcription factors.

There is also integration between Hippo signaling and Wnt signaling. The Yorkie homolog TAZ binds to Dishevelled in the cytoplasm 81. This interaction inhibits Dishevelled function, leading to reduced β-catenin signalling upon Wnt stimulation. Conversely, loss of TAZ enhances β-catenin signaling. This cross-talk is conserved in Drosophila, as loss of Yorkie in flies also enhanced Wingless (Wg) target expression in vivo 81. Similarly, some of the pro-growth, anti-apoptotic functions of the PI3K/Akt/PKB pathway were recently found to be due to phosphorylation of Mst1, providing another point of integration between known growth factor pathways and Hippo activity 82.

Until recently, the pro-growth and anti-apoptotic functions of YAP were thought to be purely cell-autonomous, acting on cell cycle regulators and inhibitors of apoptosis. However, this has changed, as a recent study identified the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligand Amphiregulin as a transcriptional target of the Hippo pathway in mammals 83, and showed that activation of YAP leads to proliferation of neighboring cells in an EGRF dependent manner. This study also demonstrated that Yorkie shows genetic interactions with the EGFR in flies, suggesting that alterations in Hippo pathway activity will have non-autonomous effects in both normal development and in cancers.

Finally, there are hints that there are as yet unidentified complexities even at the core of the Hippo pathway. A recent study 84 examined mice lacking both Mst1 and Mst2. As expected, targeted loss of Mst1 and Mst2 in the liver resulted in massive overgrowth and eventual hepatocellular carcinoma. Surprisingly, however, they found that even in the absence of MST1 and MST2, contact inhibition of MEFs occurs normally. In these MEFs, phosphorylation of Lats1 and Lat2 and Yap occur normally; therefore, there must be Lats1 and Lats2 activators other than Mst1 and Mts2 in MEFs. Similarly, when they examined the liver of Mst1 and Mst2 double mutants, YAP phosphorylation occurred, but in the absence of Lats1 and Lats2 activation. The identity of the Lats activator and Yap kinase are currently unknown.

The benefits of double duty

Even if cells are capable of effectively segregating signals that appear to pass through common elements, why take the risk? One can only speculate, but part of the answer may stem from the fact that the number of signaling pathways discovered to date is remarkably limited, given biological complexity. While there is tremendous diversity at the level of ligands and receptors, once the receptor-tyrosine kinase or G-protein coupled receptor has been engaged, there are a much smaller number of options available for transmission of signals within the cell. Moreover, despite the practical scientific need to probe cellular responses to individual signals, this scenario is hardly physiological. Cells are exposed to a veritable cacophony of signals that is constantly changing. In this reality, it is not so much that signals turn on or off, rather how they interact and integrate within the context of any given cell. Perhaps this is a clue to the preponderance of shared components in signaling? Yet given the established roles of Fat and Dachsous in regulating the Hippo pathway, and separately controlling PCP, one has to wonder if this separation is only apparent. It seems wasteful to position Fat as a key mediator of tissue growth and tissue patterning, and not to take advantage of that position to integrate those signals.

Evidence for the advantages to shared molecules is subtle, but it may be argued that it is obscured by the insulation systems discussed above – systems that are essential to avoid the chaos that would occur if there was indiscriminate information cross-contamination. Despite this, there are examples that hint at the existence of hidden underpinnings of signal transduction. The most obvious theoretical advantage of common components is cross-talk and coordination. There are many well-documented biochemical linkages between signaling pathways such as the transcriptional product of one signal being a negative regulatory protein of another (for example, the mitogens-activated protein kinase phosphatases that are induced at the transcriptional level by stresses that act through JNK and p38 MAPK which act to dephosphorylate and inactive the Erks 85). The Wnt pathway offers similar linkages such as the role of Tankyrase-mediated polyADP ribosylation in stabilizing Axin, thereby providing a new input for regulators of Tankyrase on Wnt pathway sensitivity 86. These links serve as direct and rapid coordinators that tune the activity of signals at an intensive and detailed level. The importance of these mechanisms have been particularly recognized through systems biology efforts to model short-term (minutes) pathway responses to specific triggers, such as tumour necrosis factor-α 87. There are also advantages in terms of multipurposing. The destruction complex, for example, processes not only β-catenin for degradation but also cMyc 88.This mechanism of Myc degradation is, seemingly, not regulated by Wnt but given that c-myc is an important transcriptional target of β-catenin, the common machinery at the least provides opportunity for coordination.

Less obvious inter-pathway influences occur on longer timescales (hours rather than seconds or minutes). This evidence was derived initially from developmental biology studies of model organisms that noted reciprocity of phenotypes in processes governing fundamental embryonic patterning processes such as segmental polarity where, for example, mutants in the Hedgehog pathway caused effects on Wg-regulated processes, and vice versa. These influences likely reflect programming events that attempt to compensate for reduced activities in certain pathways through sporadic loss of cells and form the basis of biological robustness. While a loss-of-function mutation that permeates all cells will usually defeat such compensatory systems, development succeeds in the face of frequent accidents as a consequence of intrinsic recalibration of cellular sensitivities to pathways. Using the canonical Wnt pathway as an example, the absolute levels of β-catenin appear less important than fold differences 89 although this may be tissue dependent as revealed by an allelic series of APC mutations 90, 91. This phenomenon has advantages in organismal adaptation and allows resetting of global cellular responses to a signal. The mechanisms by which this is achieved are being uncovered. The simple Axin2 negative feedback loop is one example but is selective for the canonical Wnt pathway. More complex loops where a regulator controls both positive and negative elements of a system can lead to changes in multiple parameters including signal amplitude, duration and sensitivity 92. Such wider impacts may be mediated by regulators like GSK-3, which has roles in not only the Wnt and growth factor and insulin signaling pathways but also regulates the Hedgehog and Notch pathways. Complete inactivation of GSK-3 leads to activation and dysregulation of β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog and other pathways, the result being an effective block to differentiation (but not cellular viability) as visualized in embryonic stem cells and neuronal precursors 14, 93. However, inactivation of 75% of this promiscuous regulator results in minimal, if any, developmental effects. Such a “non-outcome” must reflect significant correction of signaling receptivity in the background. While such changes in GSK-3 are unlikely to be physiologically relevant, the common protein may act as a tether, helping to align and adjust pathway activities.

Concluding remarks

The fact that key regulatory pathways often share components complicates their analysis and understanding of functions. Use of small molecule inhibitors or RNAi will break down the natural barriers and mechanisms of insulation resulting in these tools having an impact on multiple systems. Development of therapeutic strategies should take the linkages into consideration in estimating therapeutic windows. While a small molecule might show exquisite selectivity for its target protein, that specificity is lost if its target has a natural promiscuity that is normally held in check through sequestration, etc. Targeting selective insulating systems may provide new opportunities such that only a specific role of a target might be affected, leaving its other functions intact. Finally, the core adaptability of signaling molecules may provide natural buffering against undesired effects, if the differential sensitivities of pathways are taken into account.

Glossary Terms

- Cadherin

Family of transmembrane proteins that form homotypic, Ca2+-dependent interactions between cells, promoting adhesion

- Serpentine receptor

Type of receptor protein that traverses the membrane seven times and are typically coupled to G-proteins (also known as G-protein coupled receptors)

- Planar cell polarity

Mechanism of cellular organization distinct from apical/basal polarity which is important in providing a higher order of arrangements in flat sheets of epithelial cells

- Convergent extension

Non-mitotic developmental process involving elongation in one axis of a band (or bands) of cells, usually resulting in the coverage of a structure

- Neural tube

Precursor structure of the vertebrate nervous system that develops into the brain and spinal cord

- CRD domain

Cysteine-rich region located on the extracellular portion of serpentine receptors that is essential for binding ligands

- WW repeat

Protein motif that binds certain polyproline peptides and/or phosphorylated peptides (usually phospho-serine or phosphothreonine)

- Contact inhibition

Growth suppressive effect that occurs when epithelial cells are in physical contact

- ADP ribosylation

Post-translational modification involving the transfer of an ADP ribose moiety from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide to arginine, glutamic or aspartic acid side-chains

References

- 1.Cohen P. The role of protein phosphorylation in neural and hormonal control of cellular activity. Nature. 1982;296:613–20. doi: 10.1038/296613a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Amerongen R, Nusse R. Towards an integrated view of Wnt signaling in development. Development. 2009;136:3205–14. doi: 10.1242/dev.033910. This reference and the one following (3) provide excellent and up to date reviews of Wnt signaling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao B, Lei QY, Guan KL. The Hippo-YAP pathway: new connections between regulation of organ size and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:638–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.10.001. This reference and the one following (5) provide excellent and up to date reviews of Hippo signaling. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng Q, Hong W. The emerging role of the hippo pathway in cell contact inhibition, organ size control, and cancer development in mammals. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:188–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klingensmith J, Nusse R. Signaling by wingless in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1994;166:396–414. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Major MB, et al. Wilms tumor suppressor WTX negatively regulates WNT/beta-catenin signaling. Science. 2007;316:1043–6. doi: 10.1126/science/1141515. This paper and the one following (8) provide excellent examples of the power of proteomic approaches for unbiased assessment of pathway topology and interactions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller BW, et al. Application of an integrated physical and functional screening approach to identify inhibitors of the Wnt pathway. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:315. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosimann C, Hausmann G, Basler K. Beta-catenin hits chromatin: regulation of Wnt target gene activation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:276–86. doi: 10.1038/nrm2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jho EH, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin/Tcf signaling induces the transcription of Axin2, a negative regulator of the signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1172–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1172-1183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee E, Salic A, Kruger R, Heinrich R, Kirschner MW. The roles of APC and Axin derived from experimental and theoretical analysis of the Wnt pathway. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benchabane H, Hughes EG, Takacs CM, Baird JR, Ahmed Y. Adenomatous polyposis coli is present near the minimal level required for accurate graded responses to the Wingless morphogen. Development. 2008;135:963–71. doi: 10.1242/dev.013805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polakis P. The many ways of Wnt in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doble BW, Patel S, Wood GA, Kockeritz LK, Woodgett JR. Functional redundancy of GSK-3alpha and GSK-3beta in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling shown by using an allelic series of embryonic stem cell lines. Dev Cell. 2007;12:957–71. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.001. This paper describes the insensitivity to loss of GSK-3 alleles in embryonic stem cells and reveals a requirement for GSK-3 in differentiation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen P, Frame S. The renaissance of GSK3. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:769–76. doi: 10.1038/35096075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson G, et al. Casein kinase 1 gamma couples Wnt receptor activation to cytoplasmic signal transduction. Nature. 2005;438:867–72. doi: 10.1038/nature04170. This paper and the two following (17, 18) describe the positive role of two protein kinases in Wnt signaling that had previously been ascribed negative functions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeng X, et al. A dual-kinase mechanism for Wnt co-receptor phosphorylation and activation. Nature. 2005;438:873–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng X, et al. Initiation of Wnt signaling: control of Wnt coreceptor Lrp6 phosphorylation/activation via frizzled, dishevelled and axin functions. Development. 2008;135:367–75. doi: 10.1242/dev.013540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takacs CM, et al. Dual positive and negative regulation of wingless signaling by adenomatous polyposis coli. Science. 2008;319:333–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1151232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McManus EJ, et al. Role that phosphorylation of GSK3 plays in insulin and Wnt signalling defined by knockin analysis. Embo J. 2005;24:1571–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng SS, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling does not activate the wnt cascade. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35308–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078261. This study provides compelling evidence debunking the linkage between PI3K signals and Wnt responses, demonstrating signal authenticity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orsulic S, Peifer M. An in vivo structure-function study of armadillo, the beta-catenin homologue, reveals both separate and overlapping regions of the protein required for cell adhesion and for wingless signaling. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:1283–300. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.5.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simons M, Mlodzik M. Planar cell polarity signaling: from fly development to human disease. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:517–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen WS, et al. Asymmetric homotypic interactions of the atypical cadherin flamingo mediate intercellular polarity signaling. Cell. 2008;133:1093–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence PA, Casal J, Struhl G. Towards a model of the organisation of planar polarity and pattern in the Drosophila abdomen. Development. 2002;129:2749–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casal J, Struhl G, Lawrence PA. Developmental compartments and planar polarity in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1189–98. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00974-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rawls AS, Guinto JB, Wolff T. The cadherins fat and dachsous regulate dorsal/ventral signaling in the Drosophila eye. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1021–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00893-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang CH, Axelrod JD, Simon MA. Regulation of Frizzled by fat-like cadherins during planar polarity signaling in the Drosophila compound eye. Cell. 2002;108:675–88. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saburi S, et al. Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1010–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.179. This study provides evidence for conservation of roles between Drosophila Fat and mammalian Fat4 in PCP pathways. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casal J, Lawrence PA, Struhl G. Two separate molecular systems, Dachsous/Fat and Starry night/Frizzled, act independently to confer planar cell polarity. Development. 2006;133:4561–72. doi: 10.1242/dev.02641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sopko R, McNeill H. The skinny on Fat: an enormous cadherin that regulates cell adhesion, tissue growth, and planar cell polarity. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:717–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fanto M, et al. The tumor-suppressor and cell adhesion molecule Fat controls planar polarity via physical interactions with Atrophin, a transcriptional co-repressor. Development. 2003;130:763–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matakatsu H, Blair SS. Interactions between Fat and Dachsous and the regulation of planar cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Development. 2004;131:3785–94. doi: 10.1242/dev.01254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon MA. Planar cell polarity in the Drosophila eye is directed by graded Four-jointed and Dachsous expression. Development. 2004;131:6175–84. doi: 10.1242/dev.01550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin C, Ciruna B, Solnica-Krezel L. Convergence and extension movements during vertebrate gastrulation. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2009;89:163–92. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(09)89007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du SJ, Purcell SM, Christian JL, McGrew LL, Moon RT. Identification of distinct classes and functional domains of Wnts through expression of wild-type and chimeric proteins in Xenopus embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2625–34. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2625. This analysis provides an effective classification schema and structure/function analalysis of the Wnt family of ligands. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong GT, Gavin BJ, McMahon AP. Differential transformation of mammary epithelial cells by Wnt genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6278–86. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angers S, Moon RT. Proximal events in Wnt signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:468–77. doi: 10.1038/nrm2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torres MA, et al. Activities of the Wnt-1 class of secreted signaling factors are antagonized by the Wnt-5A class and by a dominant negative cadherin in early Xenopus development. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1123–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.5.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishitani T, et al. The TAK1-NLK-MAPK-related pathway antagonizes signalling between beta-catenin and transcription factor TCF. Nature. 1999;399:798–802. doi: 10.1038/21674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meneghini MD, et al. MAP kinase and Wnt pathways converge to downregulate an HMG-domain repressor in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1999;399:793–7. doi: 10.1038/21666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rousset R, et al. Naked cuticle targets dishevelled to antagonize Wnt signal transduction. Genes Dev. 2001;15:658–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.869201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan D, et al. Cell autonomous regulation of multiple Dishevelled-dependent pathways by mammalian Nkd. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3802–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071041898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee JM, et al. RORalpha attenuates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling by PKCalpha-dependent phosphorylation in colon cancer. Mol Cell. 2010;37:183–95. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minami Y, Oishi I, Endo M, Nishita M. Ror-family receptor tyrosine kinases in noncanonical Wnt signaling: their implications in developmental morphogenesis and human diseases. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:1–15. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato A, Yamamoto H, Sakane H, Koyama H, Kikuchi A. Wnt5a regulates distinct signalling pathways by binding to Frizzled2. Embo J. 2010;29:41–54. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsumoto S, Fumoto K, Okamoto T, Kaibuchi K, Kikuchi A. Binding of APC and dishevelled mediates Wnt5a-regulated focal adhesion dynamics in migrating cells. Embo J. 2010;29:1192–1204. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rusan NM, Peifer M. Original CIN: reviewing roles for APC in chromosome instability. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:719–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Connell MP, et al. The orphan tyrosine kinase receptor, ROR2, mediates Wnt5A signaling in metastatic melanoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:34–44. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roman-Gomez J, et al. WNT5A, a putative tumour suppressor of lymphoid malignancies, is inactivated by aberrant methylation in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2736–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oishi I, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase Ror2 is involved in non-canonical Wnt5a/JNK signalling pathway. Genes Cells. 2003;8:645–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mikels AJ, Nusse R. Purified Wnt5a protein activates or inhibits beta-catenin-TCF signaling depending on receptor context. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He X, et al. A member of the Frizzled protein family mediating axis induction by Wnt-5A. Science. 1997;275:1652–4. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Green JL, Kuntz SG, Sternberg PW. Ror receptor tyrosine kinases: orphans no more. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:536–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamamoto S, et al. Cthrc1 selectively activates the planar cell polarity pathway of Wnt signaling by stabilizing the Wnt-receptor complex. Dev Cell. 2008;15:23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clevers H. Wnt signaling: Ig-norrin the dogma. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R436–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Badouel C, et al. The FERM-domain protein Expanded regulates Hippo pathway activity via direct interactions with the transcriptional activator Yorkie. Dev Cell. 2009;16:411–20. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goulev Y, et al. SCALLOPED interacts with YORKIE, the nuclear effector of the hippo tumor-suppressor pathway in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2008;18:435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu S, Liu Y, Zheng Y, Dong J, Pan D. The TEAD/TEF family protein Scalloped mediates transcriptional output of the Hippo growth-regulatory pathway. Dev Cell. 2008;14:388–98. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang L, et al. The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Dev Cell. 2008;14:377–87. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bennett FC, Harvey KF. Fat cadherin modulates organ size in Drosophila via the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2101–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cho E, et al. Delineation of a Fat tumor suppressor pathway. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1142–50. doi: 10.1038/ng1887. This paper as well as the next two (63, 64) positions and characterises key molecules associated with Fat signalling into a pathway. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silva E, Tsatskis Y, Gardano L, Tapon N, McNeill H. The tumor-suppressor gene fat controls tissue growth upstream of expanded in the hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2081–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Willecke M, et al. The fat cadherin acts through the hippo tumor-suppressor pathway to regulate tissue size. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2090–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu J, Poulton J, Huang YC, Deng WM. The hippo pathway promotes Notch signaling in regulation of cell differentiation, proliferation, and oocyte polarity. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meignin C, Alvarez-Garcia I, Davis I, Palacios IM. The salvador-warts-hippo pathway is required for epithelial proliferation and axis specification in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1871–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Polesello C, Tapon N. Salvador-warts-hippo signaling promotes Drosophila posterior follicle cell maturation downstream of notch. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1864–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hamaratoglu F, et al. The tumour-suppressor genes NF2/Merlin and Expanded act through Hippo signalling to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:27–36. doi: 10.1038/ncb1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sopko R, et al. Phosphorylation of the tumor suppressor fat is regulated by its ligand Dachsous and the kinase discs overgrown. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1112–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feng Y, Irvine KD. Processing and phosphorylation of the Fat receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811540106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu J, et al. Kibra functions as a tumor suppressor protein that regulates hippo signaling in conjunction with Merlin and expanded. Dev Cell. 2010;18:288–99. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baumgartner R, Poernbacher I, Buser N, Hafen E, Stocker H. The WW domain protein Kibra acts upstream of hippo in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2010;18:309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Genevet A, Wehr MC, Brain R, Thompson BJ, Tapon N. Kibra is a regulator of the salvador/warts/hippo signaling network. Dev Cell. 2010;18:300–8. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oh H, Reddy BV, Irvine KD. Phosphorylation-independent repression of Yorkie in Fat-Hippo signaling. Dev Biol. 2009;335:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rogulja D, Rauskolb C, Irvine KD. Morphogen control of wing growth through the Fat signaling pathway. Dev Cell. 2008;15:309–21. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baena-Lopez LA, Rodriguez I, Baonza A. The tumor suppressor genes dachsous and fat modulate different signalling pathways by regulating dally and dally-like. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9645–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803747105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Herranz H, Milan M. Signalling molecules, growth regulators and cell cycle control in Drosophila. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3335–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.21.6996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peng HW, Slattery M, Mann RS. Transcription factor choice in the Hippo signaling pathway: homothorax and yorkie regulation of the microRNA bantam in the progenitor domain of the Drosophila eye imaginal disc. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2307–19. doi: 10.1101/gad.1820009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alarcon C, et al. Nuclear CDKs drive Smad transcriptional activation and turnover in BMP and TGF-beta pathways. Cell. 2009;139:757–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fernandez LA, et al. YAP1 is amplified and up-regulated in hedgehog-associated medulloblastomas and mediates Sonic hedgehog-driven neural precursor proliferation. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2729–41. doi: 10.1101/gad.1824509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Varelas X, et al. The Hippo Pathway Regulates Wnt/β-Catenin Signalling. Dev Cell. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.007. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yuan Z, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt inhibits MST1-mediated pro-apoptotic signaling through phosphorylation of threonine 120. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3815–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 83.Zhang J, et al. YAP-dependent induction of amphiregulin identifies a non-cell-autonomous component of the Hippo pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1444–50. doi: 10.1038/ncb1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhou D, et al. Mst1 and Mst2 maintain hepatocyte quiescence and suppress hepatocellular carcinoma development through inactivation of the Yap1 oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:425–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Owens DM, Keyse SM. Differential regulation of MAP kinase signalling by dual-specificity protein phosphatases. Oncogene. 2007;26:3203–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huang SM, et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature. 2009;461:614–20. doi: 10.1038/nature08356. This paper reveals a novel level of regulation of Wnt signaling via Tankyrase-mediated destabilization of Axin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Albeck JG, et al. Quantitative analysis of pathways controlling extrinsic apoptosis in single cells. Mol Cell. 2008;30:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arnold HK, et al. The Axin1 scaffold protein promotes formation of a degradation complex for c-Myc. Embo J. 2009;28:500–12. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goentoro L, Kirschner MW. Evidence that fold-change, and not absolute level, of beta-catenin dictates Wnt signaling. Mol Cell. 2009;36:872–84. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Buchert M, et al. Genetic dissection of differential signaling threshold requirements for the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in vivo. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yokota Y, et al. The adenomatous polyposis coli protein is an essential regulator of radial glial polarity and construction of the cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2009;61:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Goentoro L, Shoval O, Kirschner MW, Alon U. The incoherent feedforward loop can provide fold-change detection in gene regulation. Mol Cell. 2009;36:894–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim WY, et al. GSK-3 is a master regulator of neural progenitor homeostasis. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1390–7. doi: 10.1038/nn.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]