Abstract

Background

It can be difficult to explain pediatric Phase I oncology trials to families of children with refractory cancer. Parents may misunderstand the information presented to them, and physicians may assume that certain topics are covered in the informed consent document and need not be discussed. Communication models can help to ensure effective discussions.

Methods

Suggestions for improving the informed consent process were first solicited from Phase I study clinicians via questionnaire. Eight parents who had enrolled their child on a Phase I pediatric oncology trial were recruited for an advisory group designed to assess the clinicians’ suggestions and make additional recommendations for improving informed consent for pediatric Phase I trials.

Results

A Phase I Communication Model was designed to incorporate the suggestions of clinicians and families. It focuses on education of parents/families about Phase I trials at specific time points during a child’s illness, but specifically at the point of relapse. We also present an informative Phase I fact sheet that can be distributed to families.

Conclusions

Families who will be offered information about a Phase I clinical trial can first receive a standardized fact sheet explaining the general purpose of these early-phase clinical trials. Parental understanding may be further enhanced when oncologists address key themes, beginning at diagnosis and continuing through important decision points during the child’s illness. This model should be prospectively evaluated.

Keywords: physician communication, pediatric oncology, patient perspectives, ethics

Introduction

Refractory cancers are malignancies that do not respond to treatment, either due to an acquired resistance during treatment or from the beginning of standard therapy.1 Approximately 20%–25% of parents whose children have refractory cancer will continue to pursue treatment options, possibly including a Phase I clinical trial.2–4 By design, pediatric Phase I trials are not intended to assess the efficacy of a new anticancer agent but instead its safety (maximum tolerated dose), toxicity profile, and pharmacokinetics in children.

Because these studies are relatively safe (approximate 0.5% treatment related mortality) and well-tolerated (25% with grade 3 or greater toxicity)5,6, enrollment of pediatric oncology patients on Phase I trials is not unreasonable, provided that informed consent conversations (ICC) are of high quality. In our previous work, physicians estimated that approximately 73% of parents understand the risk of toxicity3, a key to understanding and appreciating the risks of trial participation. However, many parents of children participating in Phase I trials did not fully understand their purpose, and only 32% demonstrated substantial understanding.4The same study suggested that physicians do not adequately provide information about important scientific principles, such as dose finding, dose escalation, drug safety, and scientific design (dose cohorts).4 Furthermore, physicians may bypass important topics during the ICC, assuming that the information is adequately presented in the informed consent document.7 Our findings in the pediatric oncology population is consistent with other research showing that the IC process is often sub-optimal.8–10

Meaningful informed consent (IC) and (for older children, adolescents, and young adults, AYA) meaningful assent, requires that these stakeholders understand the purpose of a Phase I trial. They should also appreciate how the risks and benefits of participation apply directly to their child and how overall quality of life may be affected. Although pediatric Phase I trials have a small chance of a direct benefit of cancer control (6.8% for a single novel agent; 20.1% when combined with known active anticancer drugs)5 and place children at greater risk of toxic effects, almost all families offered enrollment on a Phase I study choose to do so.4 Other potential benefits of participation include disease stabilization, symptom relief, and the psychological benefit of maintaining hope. Parents have also reported not giving up on one’s child as a psychological benefit of participation.11 Furthermore, enrollment on a phase I trial does not appear to affect important end of life characteristics in children with cancer.12

Previous interviews with parents and AYA considering a Phase I trial have yielded some frequent suggestions for improving the informed consent process13, including providing more specific information about the trial, allowing more time for decision-making, and using mixed methods to deliver important information. Previous research with physicians on improvement of the ICC yielded suggestions such as simplification of the consent form (content, language, length), formal training of physicians, improved delivery of the information via multiple methods with patients and parents, and a multi-stage consent process.13 Communication analysis of risks and benefits of Phase I oncology trials has demonstrated that a large, complex volume of information is discussed with families (risks, therapeutic benefit, and quality of life issues) and indicates that a staged consent process may be beneficial.14

Lack of parental understanding about the purpose of Phase I research and its small likelihood of direct benefit to a vulnerable population of children is troubling.4 Parents who do not understand these factors are unable to conscientiously weigh benefits against risks that the quality of their child’s remaining lifespan may be reduced. Pediatric patients’ clinicians, medical team, and clinician-investigators have a fiduciary responsibility to promote the welfare interests of the participant, i.e., the child. One way to reduce the disparity between the expectation of high-quality informed consent and the current reality of poor parental understanding of pediatric Phase I studies is to develop and test quality improvement models. Building on our previous studies of informed consent, here we have incorporated the suggestions of participants, parents, and clinicians to propose such a communication model for quality improvement of the ICC in Phase I trials.

Methods

Parent data presented here are derived from the Parent Advisory Group on Informed Consent (PAGIC), an advisory group of parents who had experienced the informed consent process for a Phase I pediatric cancer trial and who had enrolled their child on the trial. PAGIC parents were recruited from the larger cohort of families considering participation in an open phase I pediatric cancer trial at one of six hospitals with active phase I pediatric trials.4 Research assistants at each study site directly observed the ICC and rated the 57 parents who completed study interviews according to their participation in the ICC and post-ICC study interview. Each individual parent was rated on four criteria: 1) selflessness expressed, 2) articulateness, 3) insight, and 4) engagement. Each variable was scored from 0 to 2.5, for a total possible score of 10. A score of 6 to 10 was required for inclusion. Of the 57 parents considered, 15 were eligible for the advisory group. Parents for the advisory group were invited to participate in PAGIC if: (1) the parent had completed the study interviews and agreed to further contact and (2) the parent’s child had died at least six months before the PAGIC meeting.15 The Institutional Review Board of each site approved this multi-institutional study before parents were contacted.

Two authors (A.L. & E.K.) invited the 15 eligible parents, first by letter and then by telephone. Three parents responded to the letter and agreed to participate. Five responded to the follow-up call and agreed to participate. In total, 8 parents (53%) agreed to participate in PAGIC. They had enrolled their child on a Phase I trial at one of the five children’s hospitals across the United States that were a part of the present study. Six members of the research team, including the primary investigator (PI) (E.K), study-site co-investigators (J.B., R.B.N., & S.R.), a pediatric behavioral scientist and co-investigator (D.D.), and the primary research assistant (A.L.) observed and helped facilitate the advisory group meeting.

The parents and research team met altogether for one and a half days in a central location. The meeting followed an advisory group model similar to one the study team had successfully implemented in the context of Phase III leukemia trials.16 A summary of the study’s interview and survey data was sent to participants before the meeting. The materials used at the meeting were created by two authors (A.L. & E.K.) and approved by the other participants (J.B., D.D., R.B.N., & S.R.), following minor changes. PAGIC was moderated by the primary investigator and was assisted by the other study team members. The primary investigator utilized a moderator guide to help facilitate a discussion based on study data. The discussion focused on the parents’ interpretation of the data and whether they felt that it accurately depicted Phase I informed consent. The conversation began by soliciting parents’ interpretation of the study data and explored their perception of its accuracy; it then turned to topics the parents thought were important while covering topics the researchers had prospectively identified. The meeting was audiotaped, transcribed verbatim, and reviewed for accuracy by the study research assistant.

The content of the transcripts was analyzed by 4 members of the research team (L.J, A.L., E.K, and J.B.) for the purpose of extracting important communication themes identified by the advisory group. Through an iterative process these themes were placed into a communication guide. We reviewed the data derived from our previously reported General Clinician Questionnaire3 and semi-structured adolescent and parent interviews.2,13 for the purpose of verifying that the communication themes identified by PAGIC and placed onto the communication guide were consistent with themes expressed by clinicians and families reflecting on ICC. All authors reached consensus on the communication documents for clinicians and families. The communication guide and Phase I fact sheet were sent to the PAGIC families for content review and approval. The families made minor suggestions which are included in the final model presented here

Results: Development of a Communication Guide and Phase I Cover Sheet

Demographic information on the 8 PAGIC parents compared to the rest of the sample that completed study interviews (n = 49), is presented in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups, and the smaller group of PAGIC parents is representative of the overall sample. While the main purpose of PAGIC was to solicit additional parental feedback on Phase I ICC, the parents frequently focused their discussion on improving communication with the medical team and offered suggestions both internal and external to the actual ICC. Conversations with parents during the post ICC participant interview and PAGIC indicated that the purpose of Phase I studies could be more easily understood when (1) placed into context with the purpose of later Phase studies (Phase II/III) and (2) when the purpose of the research is discussed, at appropriate times, throughout the course of the child’s illness. The advisory group believed it would be helpful if parents were given a simple cover sheet with basic factual information about the purpose of Phase I pediatric oncology trial before the ICC and suggested that a two-staged model of ICC might increase parental understanding.

Table 1.

Demographic Information on PAGIC parents compared to overall group of parents who participated in the larger Phase I informed consent study.

| PAGIC (n=8) | Overall (n=49)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 7 (88%) | 35 (35.2%) | |

| Male | 1 (12%) | 14 (13.8%) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean [SD] | 42.38 [6.21]] | 40.90 [8.18] | |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 8 (100%) | 40 (81.6%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 9 (18.4%) | |

| Index of Social Position | |||

| 1–2 | 3 (37.5%) | 16 (32.7%) | |

| 3 | 4 (50%) | 15 (30.6%) | |

| 4–5 | 1 (12.5%) | 18 (36.7%) | |

| Child’s Cancer Diagnosis | |||

| Brain and CNS | 4 (50%) | 14 (28.6%) | |

| Bone and soft tissue (sarcoma) | 1 (12.5%) | 17 (34.7%) | |

| Neuroblastoma | 1 (12.5%) | 13 (22.8%) | |

| Leukemia | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (4.1%) | |

| Other | 1 (12.5%) | 4 (8.2%) | |

| Religion | |||

| Catholic | 4 (50%) | 10 (20.4%) | |

| Protestant | 4 (50%) | 27 (55.1%) | |

| Non-Christian (Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu, Other) | 0 (0%) | 6 (12.2%) | |

| None | 0 (0%) | 6 (12.2%) | |

Demographic information is unavailable on three parents

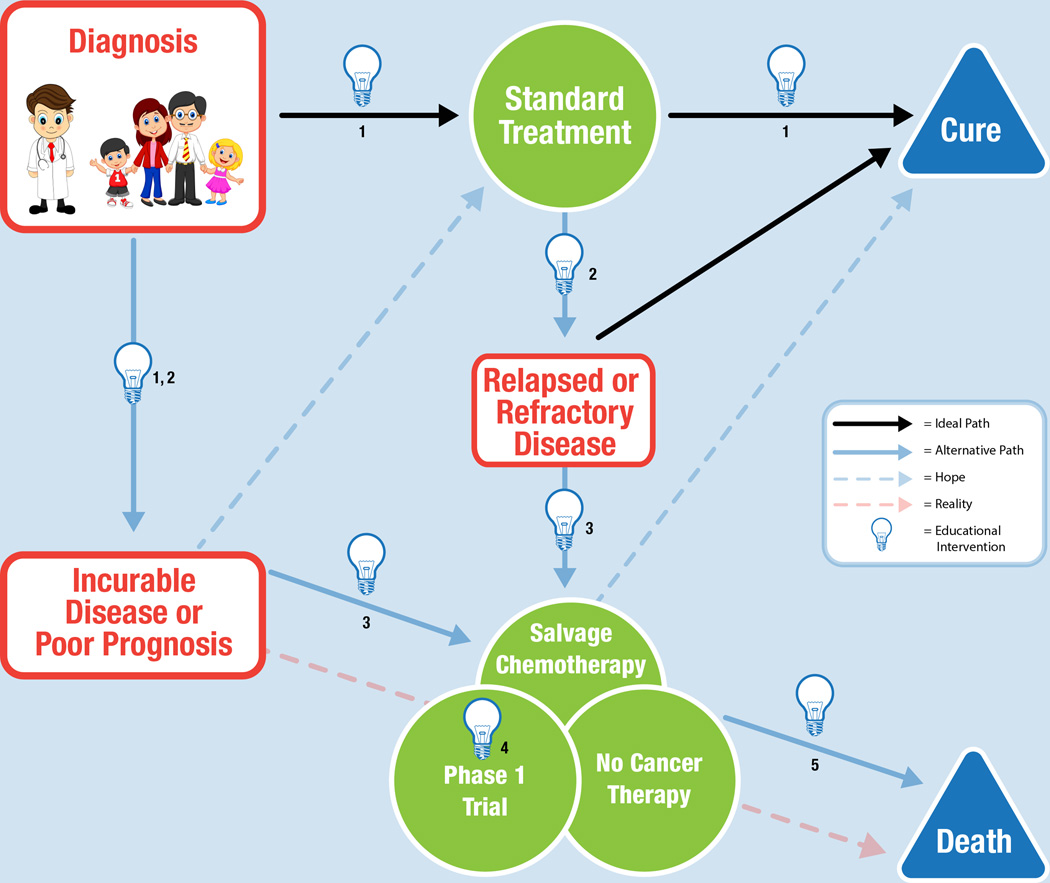

The communication themes identified from the parental transcripts were layered onto the various trajectories that a diagnosis of malignancy might follow (Figure 1). Common disease trajectories identified by the oncologists on the study team included: (1) a cancer diagnosis with a favorable prognosis often followed by cure; (2) a cancer diagnosis with an unfavorable prognosis, often followed by death; and (3) a cancer with an intermediate prognosis or relapse, with unclear outcome. Thematic content from our previous work with clinician, parent, and adolescent stakeholders,2,3,13 was reviewed in greater detail for the purpose of confirming that the communication topics and timing identified in this analysis of the PAGIC transcripts was consistent with statements made by a larger group of clinician and family stakeholders in the context of our earlier Phase I research. The model includes illustrative quotes from the PAGIC study group, with supportive statements from our previous physician questionnaire added for additional clarity.

Figure 1.

Communication model for improving understanding in families whose child has a diagnosis of malignancy.

Discussion

High-quality informed consent is crucial to ethical pediatric Phase I cancer research, yet the current paradigm of single ICC sessions of 45–60 minutes is inadequate to ensure parental understanding, even when physicians explain all of the key scientific concepts (drug safety, dose finding, and dose escalation) and solicit research-related questions from parents (average, 15.6 questions asked).4 Although our focus was on parental understanding at the time of the Phase I ICC, stakeholders identified model behaviors at time points from diagnosis through the end of life due to refractory cancer, including a two-stage Phase I ICC that would foster parental understanding and improve the quality of the Phase I ICC.

Intervention 1: Anticipatory Guidance

Improved clinician communication with families can begin at the time of diagnosis (Figure 1, Intervention 1). At this time, families understandably want conversations that focus on cure. However, most childhood cancer is treated on a clinical trial or a standard-of-care regimen based on a trial, and families want education about clinical trials from the start. They suggested the use of visual as well as written materials for this type of education. Physicians should focus on individual concepts (risks, benefits, goals, objectives, and logistics) and assess parents’ understanding of each concept before moving on to the next, rather than weaving between concepts. As one parent indicated, “…sticking to the concepts and using examples.”

After treatment begins, physicians should offer parents anticipatory guidance before the response to treatment is assessed, providing an opportunity for “what if” conversations about the possibility of relapse or refractory disease. If families are willing to engage the physician, he or she can discuss Phase I/II clinical trials, salvage chemotherapy, and comfort-directed therapy alone. Parents are often anxious before assessments of response to treatment, and these conversations might allow them to explore and face their fears about receiving bad news. The PAGIC represented as subset of parents whose children died from progressive cancer, therefore one limitation of the model is that their retrospective suggestions on communication at Intervention 1 may not be generalizable to families whose oncology course is relatively unremarkable (example, low-risk ALL without significant symptom burden related to therapy). Given the research demonstrating poor parental understanding and sub-optimal communication in the context of Phase III leukemia ICC16, we believe these communication tips are still applicable regardless of a child’s ultimate disease course.

Intervention 2: Conversations at Relapse or Poor Prognosis

When a child’s cancer has relapsed or is refractory, or incurable (Figure 1, Intervention 2), the parents involved in PAGIC, who had lost their child, requested straightforward, honest medical information about the prognosis, even when grim.17,18 Physicians should assess what level of information parents desire and empower them to make informed decisions, including their child when possible. Training programs designed to teach physicians and nurses strategies for initiating and continuing palliative care and end-of-life conversations with families may improve the quality of these conversations.19

Intervention 3: Introduction of Options

If families are to be offered enrollment on a Phase I trial (Figure 1, Intervention 3), clinicians should strive to allow appropriate hope20 even though the likelihood of survival is low, the child may receive other benefits from trial participation, such as improvement of symptoms and quality of life. Altruism is another motivation for study participation, as is hope for direct or indirect benefit to their child. For the parent, the enrollment decision is a “head versus heart” struggle. The head knows that survival is unlikely, but the heart needs to believe there is hope. Allowing families to openly discuss their fears and hopes, and involving supportive services, such as psychology, palliative care, and spiritual care can help in this process. It should be clarified to parents that palliative care is not hospice care. Palliative care is care given by a team of experts to improve the quality of life of patients with a serious illness such as cancer and focuses on symptom management and decision-making as well as related psychological, social, and spiritual problems.21

Families are interested in researching treatments and want to know about all available trials and treatment options and when they will become available. At this time parents often have fears not directly related to the study drug, but study participation. Fears of getting “kicked off” of a trial (for using supplements or other complementary therapies) or of becoming ineligible for a trial were emphasized to a surprising extent in the PAGIC meeting and should be addressed, when applicable. Clinicians can help families process their options by openly answering their questions and discussing the risks and benefits of the various options. Allow enough time for patients and families to discuss their options and let them know that they need not decide “right now.” Clinicians should address parents’ fear that unless they make a rapid decision they risk losing their child’s “spot” in a trial. It may be important to reiterate that not only can they take time to make the decision after the ICC, but if they later feel uncertain they may withdraw from the trial at any time.

At present there are approximately 21 pediatric oncology centers that conduct Phase I clinical trials, some with dedicated Phase I teams.22 If there is a change in the primary oncologist, especially when the family transfers to a different treatment center, clinicians should be mindful that their help is needed to facilitate the transition and should facilitate a warm handoff. In a warm hand off the current clinician verbally communicates with the receiving clinician and personalizes the transition rather than communicating electronically.23 It is important to families that continuity with the primary oncologist is maintained while trust is being established with the new oncologist or center.

Intervention 4: Phase I Informed Consent Conversations

The Phase I ICC (Figure 1, Intervention 4) should be informative and delivered with sensitivity; whenever possible, it should work to build a partnership with the family.23–26 Families have identified model clinician behaviors that are helpful during difficult conversations, including empathy, physical presence (eye contact, engaged body language), repetition of information at multiple time points, and an ongoing invitation to ask questions. Families are also interested in information about the experience of other children enrolled on the trial and wish to receive regular study updates should they enroll. Importantly, families want clinicians to make a recommendation and to help guide their decision. As clinicians have expertise and experience that families do not have, it is not paternalistic to offer direction to those who are struggling with a life-altering decision.13

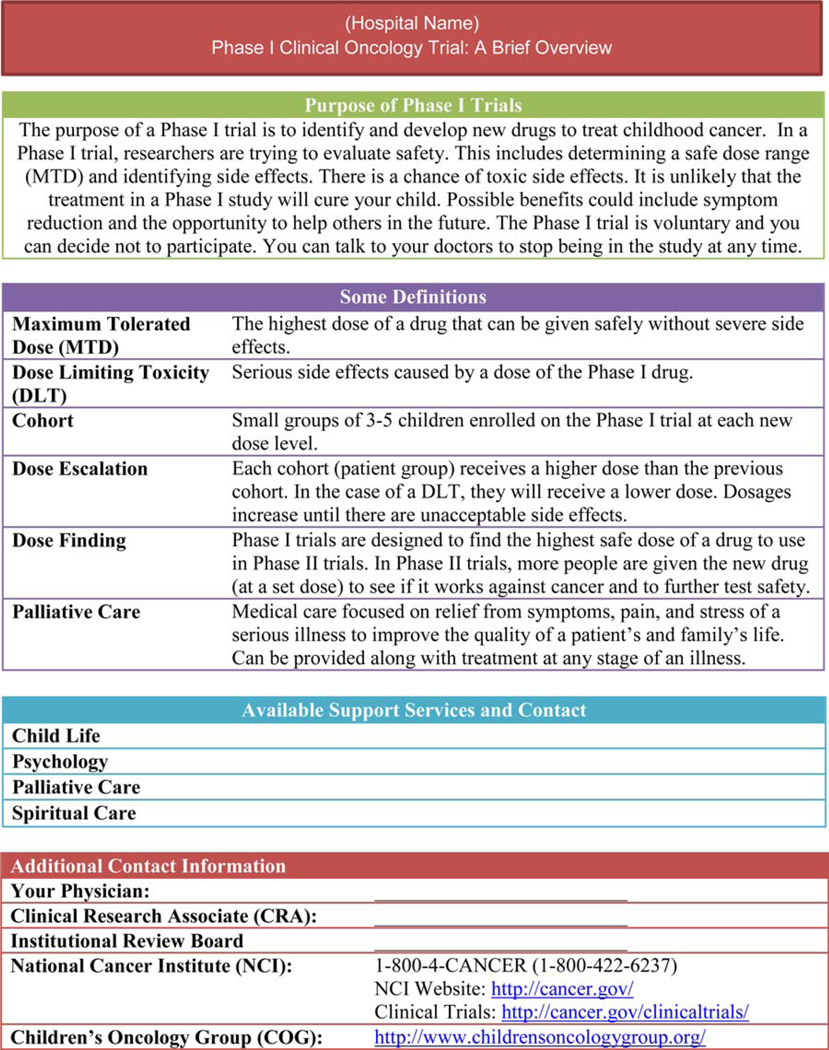

Given the large amount of information that must be discussed in a Phase I ICC, it is important to re-evaluate the manner in which families receive the logistical information about the trial, including risks and benefits. One key to improving the quality of the ICC is to increase parental understanding of the purpose of the study. Our previous research on informed consent for Phase III trials supported the use of a consent process model that is multi-staged, so that it can cover key scientific topics before introducing trial-specific details. We propose that a simple Phase I fact sheet, written in simple lay terms, be provided to all families (in their native language) who will be offered enrollment in a Phase I trial. As one parent suggested, “I think it should be presented at an 8th grade level, because then everyone should be able to understand it.”

The PAGIC group developed a simple explanation to be included on the fact sheet, outlining the basic purpose, risks and benefits, and voluntary nature of a Phase I trial (Figure 2). Although the information may appear in different forms, the fact sheet should cover basic principles such as dose escalation and maximum tolerated dose (Figure 2). Parents at PAGIC developed the following statement to describe Phase I trials to parents: “The purpose of Phase I trials is to determine safe doses of new drugs. It is highly unlikely any of these drugs would cure your child. Potential benefits could include symptom reduction and the opportunity to help others in the future. There is the potential for adverse side effects.” This definition has been expanded upon in the cover sheet to include other basic tenets of the Phase I consent process that the parents defined as critical to understanding. It should also include information about the medical team and contact information for supportive services. Alternative methods (examples: a cartoon, drawings, a short video, an iPad presentation) are encouraged to reach parents and children with different learning styles and educational levels. Culturally sensitive materials should be developed with input from members of the appropriate racial/ethnic groups. Providing supplementary educational materials and protocol summaries in advance of the ICC, is a form of anticipatory guidance that will allow families more time to process the information and think of questions. A two-stage, multi-meeting ICC process uses the basic idea of building on previously digested information; it will allow members of the multidisciplinary team to repeat concepts, check for understanding, and reinforce the purpose of the trial.

Figure 2.

Suggested coversheet for Families Considering Enrollment in a Phase I Clinical Trials.

Intervention 5: Options towards End-of-Life

In presenting information about a Phase I trial, clinicians should discuss the options of salvage chemotherapy or a focus on comfort-directed care with no further cancer-directed therapy (Figure 1, Intervention 5). Conversations should include the impact of these options on the child’s quality of life and establish that family goals may shift from an aggressive cancer-fighting approach to a comfort-directed approach at this point or at any time in the future. Families of children with complex medical conditions and the possibility of impending death have identified broad categories that help to smooth this transition and facilitate coping.27 These categories are: (1) having expectations of the illness and likely progression, (2) continuity of care by the clinical team, (3) altruism, (4) memory making, and (5) having a wide network of support. If not already included, palliative care and end-of-life planning discussions can be integrated into the pathway, with reinforcement that Phase I therapy and palliative care can be offered concurrently. One parent made the statement, “…see how you can empower the parent and see how you can empower the child. Be honest, ok? Find out what their support system is - you know, if you need an advocate - also spiritual help. I mean you really have, you can’t ignore that point-of-view…end-of-life planning and so on.”

Conclusion

The decision to enroll on a Phase I trial is one of the most difficult decisions parents and children face28; families want physicians to recognize the difficulty of this decision and deliver information that is tailored to their needs and their medical situation. Decision-making has shifted from a historically paternalistic approach where decision-making was primarily physician driven to a more autonomous, patient-driven approach. However, complex medical decisions such as enrollment on a clinical trial are best reached via shared decision making, in which the clinician spends time educating families about the trial and helping them weigh the risks and benefits in the context of their own values and preferences. Quality ICC requires a high level of focused engagement by the physician and should be considered more than a straightforward disclosure session with neutral provision of information.

The intent of the PAGIC endeavor was to ask parent stakeholders to provide comments and suggestions for improving the Phase I ICC. Unprompted, the parents consistently advocated that improvements in communication at Phase I were only likely to occur if communication was improved throughout the cancer experience. To most accurately reflect this stakeholder feedback we designed a model that integrated the suggested communication practices into important decision points throughout the entirety of a child’s illness trajectory, culminating with a two-stage conversation at the point where Phase I is offered. The next step in our quality improvement efforts will be to educate clinicians on how to conduct these high-quality conversations and to distribute the Phase I fact sheet to families. Our goal is future research with stakeholders and measuring outcomes against those of a historical control group.

Interventions to improve informed consent are needed, particularly in Phase I pediatric oncology research, in which patients may be exposed to toxic effects of therapy with little chance of direct benefit. We believe that this model is a starting point for improving the quality of conversations that oncologists have with families whose children have advanced cancer and is one which can be easily integrated into practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the eight parents who participated in the Parent Advisory Group on Informed Consent and the parents, patients, and physicians involved in the study. We would also like to thank Sabahat Hizlan in the Cleveland Clinic Department of Bioethics for her assistance on data analyses.

Funding Source: National Institutes of Health grant 1R01CA122217

Abbreviations

- ICC

informed consent conference

- PAGIC

Parent Advisory Group on Informed Consent

- AYA

adolescent and young adult

Appendix

| Time Point |

Suggested Topics | Parent Quotes | Physician Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Disclosure of Diagnosis

|

Just so they feel more comfortable talking about it [diagnosis] and they know how to speak about it… How the same thing can be said in different ways, but it just comes across that much better to the family if it’s phrased in this way. | …develop a more comprehensive process that should include visual as well as written materials and verbal communication and should take more than one session to allow for the parents to quietly read and understand the material provided. |

| Clinical Trial Education (& Likely Enrollment) | There is a lot of concepts going on, we’re talking about dose escalation, toxicity, and I realize that a lot of these that the physicians are melding it and we’re going one to the other and it’s almost like teaching people to talk in paragraphs. | The informed consent documents (Phase 1, 2 or 3) are currently often 30 pages long. There is so much “required language” that points unique to that person are lost in the repetitive language. Consents could be simplified to improve patient understanding. | |

| 2 |

Discussion of Prognosis

|

Just so they feel more comfortable talking about it and they know how to speak about it. We can give them guidelines on how, this is how to, you gave an example on how to simply phrase something. How the same thing can be said in different ways but it just comes across um, that much better to the family if it’s, you know, phrased in this way. | I know that it has to be “standard,” but each family is so different, it would help to have different levels of information, i.e. an extra packet for smart, savvy families, giving them things like the background science. Having different communication means for the young adults – like something they can download onto their iPod and listen to. |

Researching Treatment

|

I knew all about this trial, I knew the details, everything on this trial before I walked into that consent. I had a stack every week of at least 5–10 different trials going on that I plowed through with my doctor and we would go through them and my daughter was involved in it. Does it make you lose your hair? Nope! Don’t want it. I mean she was right there and yes, she had different focuses than I did but my point was is I went into this trial knowing every detail about it before I went into the consent. | Allowing enough time to go over the child's current status, lack of known curative therapies, options for further care, intent of Phase 1 studies, review of study and potential toxicities is important. | |

| Discussing Fears | I think it’s important that the discussion and the people that are involved in this feels comfortable enough to openly include these things because if you are afraid that you’re going to be kicked off the trial because you’re on a medicine, you’re not going to say something. | ||

| Consult Supportive Services (PC, Psychology, etc.) | When I was in, at [hospital] you know, you go through all of these kinds of phases and I finally said, “You know what? I need to speak to a nutritionist.” And they were like, “Oh, thank God you asked,” and I was like, “What do you mean thank God I asked?” They said, “We can’t offer that service unless you ask for it.” I said, “Excuse me?” And then I said the same thing about um, um, psychological services. And they were like, “We do have a doctor but you have to ask for that service.” And I’m like, again, these service should be part of the whole package because parents don’t know to ask. | Adding session that includes other disciplines such as SW, psychology, or RN that does not include MD | |

| 3 | Maintaining Hope | The first word is always hope, past the hope I am hoping that this helps somebody in the future. I am hoping it helps me but we are also hoping that this goes, this helps somebody else and they don’t have to go through the same thing. | I want my patients to have hope for quality life prolongation without letting that influence their decision whether or not they consent to a phase one study. |

| Trial Availability / Time to Weigh Options | P1: It was like whoever had the fastest finger is the one that got on the trial. P2: Exactly, it was a race to the finish line. P1: And theres 3 spots in the whole United States and you are like “I will sign anything you want me to.” |

P1: Sometimes the deadlines for reservations on Phase I studies force the consent process to occur at a faster rate, the potential to extend these reservations could be helpful for the particular patients, although may delay the conduct of the study. P2: Time between relapse and discussing/ensure decision by family to enroll of trial. |

|

| Well I think time is a big player in that too because I know we experienced it’s almost as if you need to make a decision quickly, you know? This relapse, you don’t have time, we don’t have time to look at these alternative way of doing things. You need to make a decision, here’s the trial that we have. We don’t have a lot of time to look outside of the box. | |||

| Continuity of Care: facilitating transitions (to new center or MD) | I felt that level of security with my son’s physician as where we had to trust they were sending us to a place that I could then trust this new person. | ||

| 4 | Trial Overview: Presentation, scientific background, location of clinical trial | It’s all about how it’s presented, I think, I mean in some cases you know, if you hand a parent a piece of paper and tell them to read it, you know, it’s overwhelming but you have someone like you just did, where you know, a simple diagram. I mean you just did a very simple diagram and anybody on any educational level, I think, would be able to understand that and get it. It’s all about who is presenting it and how they’re presenting the information. | Maybe also a 2-step consent, so families can absorb the details of the information they are given |

| “Model” behavior of Phase I clinicians/researchers | I just think that if they asked open ended questions, that is the main thing that they, you know, they tell you what it is and then they had you repeat back and say “Ok, can you tell me your understanding?” To make sure that you understand, but I would prefer that it would come from my oncologist, my doctor. | Spending lots of time, answering questions. LISTENING more and talking less. | |

Quality Informed Consent Conversations

|

I was thinking more and more they talked to me about this, maybe they could have like a pamphlet or an outline. I mean, yeah, take them to a conference and give them a pamphlet or an outline for them to go by because, let’s be realistic, some uh doctors just are you know, rough. They’re smart in the brains but they’re um, when it comes to the emotional part they just don’t know how to do it. | A staged consent process works better – you can then review disease progression in one meeting, perhaps have a broader decision making meeting to discuss quality of life issues, family resources, stressors in context of child’s prognosis and review options for moving forward including concept of Phase I agents. By the time you get to the actual Phase I consent meeting, you will likely have explained concept of Phase I, reviewed options for Phase I and reviewed rationale for choice of particular Phase I (preclinical data, QOL issues, etc). The consent process then concentrates more on schedule of drug administration, toxicities, correlative studies. | |

| Make Recommendations | You have to be sympathetic to these people that they’re going through life altering situations but you have to be bold. They’re relying on you who have lived this every single day of your life, you will understand the consequences. We don’t, we’re freshman in high school, we don’t know any of this stuff. We’re relying in you guys to tell us which direction we need to go to, not necessarily with the decisions but how to handle it. | The most challenging question that I face from parents is: “What would you do if this is your child?” | |

| Altruism | If it’s not going to help my child, if it’s going to save some other child from going through this or some other parent going through this then yes, I would do my child. I mean, it’s not hurting her any worse than what… the end result was going to be the same. It’s not hurting her to try. | No matter how you phrase it, families are going to perceive it as something that will potentially help their child. At least get some quality of life if not cure. To some extent they are also motivated by altruism. | |

| 5 | Changing Goals - Comfort | Your goal is not, our goal is different from your goal. We know darn well the trial is to figure out the doses and what’s the best way to… we all know that but that’s not in our heart what we’re on it for. | I think we need to be clearer with patients about the unlikeliness of benefit while still maintaining hope – hope of cure (though unlikely), hope of improvement of symptoms, hope of benefiting others, hope of peaceful death. |

| End of Life Planning | (Patient) desperately wanted to live and when he knew he was not going to make it, he wanted to help the next kid and that is from his mouth. I mean he – and at the very end of his life we had signed hospice, he wanted to make sure that his brain be donated to study. I mean he just wanted to help the next kid. | Broad discussion of options including palliative care | |

| All Time Points | Building trust & Relationships | Tremendous care and honesty. No matter how good or bad the news he always told me the truth in a way I could understand and process. He was sensitive to our needs and we felt safe under his care. | Spend as much time as the family needs to understand process. Patience, time, clear language delivered in sensitive manner. |

| Fostering Open Communication | So if they, the doctors, are open enough in saying…we need to know because it’s important but you’re not going to, you know, but open communication back and forth is vitally important in this incidence because you know, let’s face it, if we are in this trial we are desperate. We are seeking something out there. | The text of the consent is important, but I believe in the words spoken in a discussion about research at the moment a study is presented to a child/family. Education in staff involved in such an important process is central in good clinical practice. People need to go over info on multiple occasions, and preferably with multiple staff members. Must have good support from interpreters for low English proficiency families. |

|

Shared Decision Making

|

He was 11 when he was diagnosed and you guys are right, they (patients) do progressively age and become wise beyond their years as the disease progresses. So he, you know, he wanted to be engaged and when we got to (hospital) those people there were surprised just how much, and he was 12 at the time, just how much he knew about what was going on. So when it came to the consent part of it, you bet he wanted to be a part of it. | More information and better information to engage the children and adolescent so that they can better understand what it means. | |

| Voluntariness & Goals of Research | 2 page consent about purpose risks and benefits and voluntary nature. |

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None of the authors (Johnson, Leek, Drotar, Noll, Rheingold, Kodish, Baker) have any relevant financial disclosures.

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors (Johnson, Leek, Drotar, Noll, Rheingold, Kodish, Baker) have any relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. [Accessed 10/29/14]; http://www.cancer.gov/dictionary?cdrid=45863.

- 2.Miller VA, Baker JN, Leek AC, Hizlan S, Rheingold SR, Yamokoski AD, et al. Adolescent perspectives on phase I cancer research. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:873–878. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yap TY, Yamokoski AD, Hizlan S, Zyzanski SJ, Angiolillo AL, Rheingold SR, Baker JN, Kodish ED. Informed consent for pediatric phase 1 cancer trials: physicians' perspectives. Cancer. 2010;116(13):3244–3250. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cousino MK, Zyzanski SJ, Yamokoski AD, Hazen RA, Baker JN, Noll RB, Rheingold SR, Geyer JR, Alexander SC, Drotar D, Kodish ED. Communicating and understanding the purpose of pediatric phase I cancer trials. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(35):4367–4372. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee DP, Skolnik JM, Adamson PC. Pediatric phase I trials in oncology: an analysis of study conduct efficacy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(33):8431–8441. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decoster G, Stein G, Holdner E. Responses and toxic deaths in Phase I clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 1990;1:175–181. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a057716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koyfman S, Reddy CA, Hizlan S, Leek AC, Kodish E on behalf of the Phase I Informed Consent Research (POIC) Team. Informed consent conversations and documents: A quantitative comparison. Submitted for review. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynoe N, Sandlund M, Dahlqvist G, et al. Informed consent: study of quality of information given to participants in a clinical trial. BMJ. 1991;303:610–613. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6803.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lesko LM, Dermatis H, Penman D, et al. Patients’, parents’, and oncologists’ perceptions of informed consent for bone marrow transplantation. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1989;17:181–187. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950170303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, et al. Quality of Informed consent in cancer clinical trials. Lancet. 2001;358:1772–1777. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06805-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mauer SH, Hinds PS, Spunt SL, Furman WL, Kane JR, Baker JN. Decision making by parents of children with incurable cancer who opt for enrollment on a phase I trial compared with choosing to do not resuscitate/terminal care option. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(20):3292–3298. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine DR, Johnson LM, Mandrell B, et al. Does Phase I Trial Enrollment Preclude a “Good Death”? Phase I Trial Enrollment and End of Life Care Characteristics in Children with Cancer. Cancer. 2014 Dec 29; doi: 10.1002/cncr.29230. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker JN, Leek AC, Salas HS, Drotar D, Noll R, Rheingold SR, Kodish ED. Suggestions from adolescents, young adults, and parents for improving informed consent in phase 1 pediatric oncology trials. Cancer. 2013;119(23):4154–4161. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hazen RA, Zyzanski S, Baker JN, Drotar D, Kodish E. Communication about the risks and benefits of phase I pediatric oncology trials. Contemp Clinical Trials. 2015;41:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akard TF, Gilmber MJ, Miller K, et al. Factors affecting recruitment and participation of bereaved parents and siblings in grief research. Prog Palliat Care. 2014;22(2):75–79. doi: 10.1179/1743291X13Y.0000000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eder ML, Yamokoski AD, Wittmann PW, Kodish ED. Improving informed consent: suggestions from parents of children with leukemia. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):e849–e859. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):5265–5270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5636–5642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendricks-Ferguson V, Kane J, Pradhan K, Shih CS, Gauvain K, Baker J, Haase JE. Evaluation of physician and nurse dyad training to deliver a palliative and end-of-life communication intervention. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2015 Jan 26; doi: 10.1177/1043454214563410. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller VA, Cousino M, Leek AC, Kodish ED. Hope and persuasion by physicians during informed consent. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(29):3229–3235. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Cancer Institute. [Accessed July 30, 2014];Palliative care in cancer. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Children’s Oncology Group. About Us. [Accessed July 30, 2014]; [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter CL, Goodie JL. Operational and clinical components for integrated-collaborative behavioral healthcare in the patient-centered medical home. Fam Sys Health. 2010;28(4):308–321. doi: 10.1037/a0021761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leventon M Committee on Bioethics. Communicating With Children and Families: From Everyday Interactions to Skill in Conveying Distressing Information. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1441–e1460. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orioles A, Miller VA, Kersun LS, Ingram M, Morrison WE. “To be a phenomenal doctor you have to have the whole package”: physicians’ interpersonal behaviors during difficult conversations in pediatrics. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(8):929–933. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussion, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1203–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan JS, Docherty SL, Barfield R, Brandon DH. Addressing parental bereavement support needs at the end of life for infants with complex chronic conditions. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(5):579–584. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, Powell B, Srivastava DK, Spunt SL, Harper J, Baker JN, West NK, Furman WL. “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made a phase I terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):5979–5985. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]