Abstract

Autologous peripheral stem cell transplantation (AutoHCT) is commonly an inpatient procedure. However, AutoHCT is increasingly being offered on an outpatient basis. To better characterize the safety of outpatient AutoHCT, we compared the outcome of 230 patients who underwent AutoHCT on an inpatient (IP) versus outpatient (OP) basis for myeloma or lymphoma within a single transplant program. All OP transplants occurred in a cancer center day hospital. Hematopoietic recovery occurred earlier in the OP cohort, with median time to neutrophil recovery of 10 vs. 11 days (p<0.001) and median time to platelet recovery of 19 vs. 20 days (p=0.053). 51% of the OP cohort never required admission, with this percentage increasing in later years. Grade 3–4 non-hematologic toxicities occurred in 29% of both cohorts. Non-relapse mortality at one year was 0% in the OP cohort and 1.5% in the IP cohort (p=0.327). Two year progression-free survival was 62% for OP vs. 54% for IP (p=0.155). One and two year overall survival was 97% and 83% for OP vs. 91% and 80% for IP, respectively (p=0.271). We conclude that, with daily outpatient evaluation and aggressive supportive care, outpatient AutoHCT can result in excellent outcomes for myeloma and lymphoma patients.

INTRODUCTION

High-dose therapy with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HDT/AutoHCT) is now well established as an effective therapy for multiple myeloma (MM) and lymphoma (1–6). Historically, due to logistical issues and concerns regarding infection and other possible toxicities, HDT/AutoHCT has been performed in an inpatient setting. However, with improvements in supportive care and careful patient selection, it has become possible to perform HDT/AutoHCT on an outpatient basis (7–10).

With advancements in AutoHCT such as use of broad spectrum antibiotics, peripheral blood derived hematopoietic stem cell products, improved anti-emetics, and approaches to reduce mucosal toxicity, transplantation has become feasible in an outpatient setting (11–13). Outpatient transplants may offer benefit to patients in terms of enhanced comfort, shorter hospital length of stay, decreased exposure to sick contacts, and decreased costs and resource utilization (9, 12, 14).

In 2007, the Medical College of Wisconsin and Froedtert Hospital began an outpatient-based AutoHCT program. To characterize the safety of outpatient AutoHCT, we analyzed all myeloma and lymphoma patients who underwent melphalan or BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan) AutoHCT between 2009 and 2012. We directly compared the outcomes of patients undergoing AutoHCT on an outpatient versus inpatient basis, with special attention on toxicities and complications encountered.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

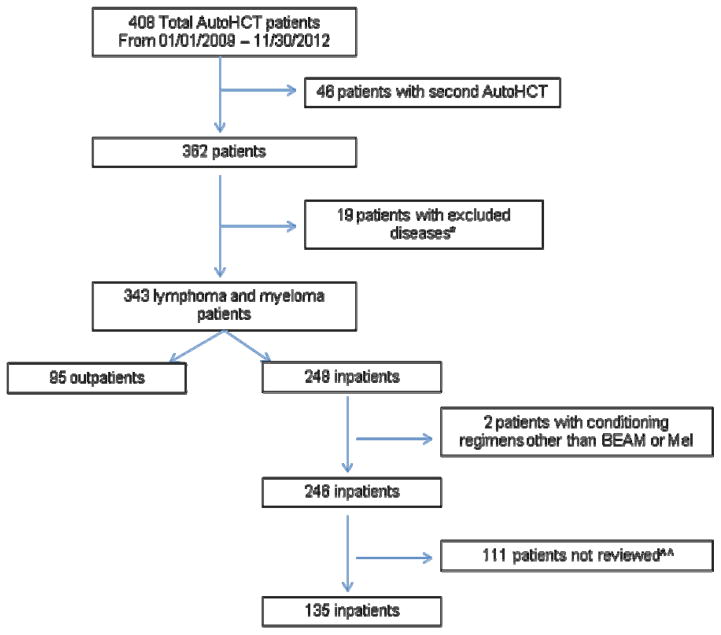

We performed a retrospective cohort study of 230 patients who underwent a first AutoHCT between July 1, 2009 and November 30, 2012 for myeloma or lymphoma using melphalan or BEAM conditioning. Patients with AL amyloidosis were not included in this study since these patients typically had much higher levels of comorbidity and all were managed on an inpatient basis. All patients were treated within the Medical College of Wisconsin & Froedtert Hospital Blood and Marrow Transplant Program. There were 135 inpatients (IP) and 95 outpatients (OP) selected for study. This included all 95 lymphoma and myeloma patients transplanted on an outpatient basis during that timeframe. The 135 patients transplanted on an inpatient basis represented 55% of all lymphoma and myeloma patients transplanted (using BEAM or melphalan, respectively) during the timeframe of interest. After statistical consultation, it was decided that 135 patients would provide sufficient data for comparison to the outpatient cohort. These 135 patients were randomly chosen across the timeframe of interest, keeping the proportion of myeloma and lymphoma patients similar to that in the outpatient cohort. A CONSORT diagram is presented in Figure 1. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Medical College of Wisconsin.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

*Including Amyloidosis, Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Germ cell tumor, Testicular cancer, Sarcoma, Scleroderma, and Light Chain Deposition Disease

^^After statistical consultation, it was decided that 135 patients would provide sufficient data for comparison. These patients were randomly chosen.

Criteria for consideration for the outpatient AutoHCT program were based on expected compliance, proximity to the cancer center for daily visits, 24-hour caregiver support, favorable performance status, and co-morbidity profile. Patients meeting criteria were then given the option to participate in the outpatient program. Patients admitted at any point after beginning outpatient transplantation were analyzed as part of the outpatient cohort, since that was the intended mode of treatment.

Data was abstracted using the EPIC electronic medical record system as well as the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) database. Demographics for each cohort are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient, Disease, & Transplant Characteristics

| Inpatient N=135 (%) |

Outpatient N=95 (%) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Transplant | |||

| Median (range) | 59 (21–76) | 58 (20–76) | 0.418 |

| Sex | 0.683 | ||

| Male | 86 (63.7) | 63 (66.3) | |

| Female | 49 (36.3) | 32 (33.7) | |

| KPS | <0.001 | ||

| </=80 | 36 (26.7) | 6 (6.3) | |

| 90 | 72 (53.3) | 49 (51.6) | |

| 100 | 27 (20.0) | 40 (42.1) | |

| HCT-CI | 0.060 | ||

| 0–2 | 64 (47.4) | 57 (60.0) | |

| 3+ | 71 (52.6) | 38 (40.0) | |

| Malignancy | 0.859 | ||

| Myeloma | 88 (65.2) | 63 (66.3) | |

| Lymphoma/Other* | 47 (34.8) | 32 (33.7) | |

| Disease Status | 0.241 | ||

| Chemo-Resistant | 5 (3.7) | 7 (7.4) | |

| Chemo-Sensitive | 130 (96.3) | 88 (92.6) | |

| #CD34(x106)/kg median (range) | 4.6 (1.9–16.5) | 4.4 (1.9–12.9) | 0.581 |

| Conditioning Regimen | |||

| BEAM | 45 (33.3) | 32 (33.6) | 1.000 |

| Mel 140 | 17 (12.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0.0008 |

| Mel 200 | 71 (52.6) | 57 (60.0) | 0.283 |

| Other** | 2 (1.5) | 5 (5.3) | 0.128 |

| Length of Stay | |||

| Median LOS, days (range) | 19 (13–36) | 0 (0–44) | <0.001 |

| Mean LOS, days (95% CI) | 19.2 (18.6–19.8) | 5.4 (3.9–6.9) | <0.0001 |

POEMS, Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia, Plasma Cell Leukemia

Inpatient: Mel 120, Mel 160

Outpatient: Mel 160, Mel180, Mel Unknown (n=2), Mel 200/Vel

Management of Outpatient Cohort

Patients undergoing AutoHCT in the outpatient program received all of their care in an outpatient day hospital contained within the Froedtert/Medical College of Wisconsin Clinical Cancer Center. The day hospital is an outpatient center established for patients needing intravenous antibiotics, chemotherapy, blood products, other types of infusions, or advanced services that might otherwise require hospitalization. Patients were required to have daily visits with labs (comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count) and supportive care (including line care, fluids, transfusions, etc) from start of conditioning until hematopoietic recovery. Patients were evaluated daily by a BMT physician and/or mid-level provider. During the day, physician coverage was provided by the patient’s primary transplant physician and after hours, by the inpatient BMT team. The day hospital was fully functional on weekends and holidays and run by a full nursing staff, pharmacist, hematology fellow or resident, and BMT physician. If deemed necessary, patients were admitted to the inpatient BMT unit. Though no specific criteria were created for admission, reasons typically included neutropenic fever, persistent diarrhea, inability to maintain adequate oral intake, uncontrolled pain, or hemodynamic instability.

Conditioning Regimens

Myeloma patients received the standard chemotherapy regimen of melphalan (typically 200 mg/m2) or in rarer circumstances, melphalan plus bortezomib. A minority of myeloma patients were treated with reduced doses of melphalan. With the exception of two patients, lymphoma patients received the BEAM conditioning regimen. The two lymphoma patients who received non-BEAM regimens were not included in the study, due to a different toxicity profile of those conditioning regimens. To make the inpatient and outpatient cohorts more comparable, the rare lymphoma patients who received conditioning regimens other than BEAM were not included in this analysis, since such regimens were not offered on an outpatient basis.

Supportive Care

Prior to conditioning, all patients had central catheters placed, either a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) or a tunneled chest wall central line. Outpatient supportive care included daily line care, anti-emetics, intravenous hydration, electrolyte replacement, and transfusion support. Patients received oral fluconazole and acyclovir for anti-fungal and anti-viral prophylaxis, respectively.

Two significant differences between the inpatient and outpatient cohorts were the type of antibiotics and hematopoetic growth factors administered. Once the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) dropped below 500/μL, the inpatient cohort received ciprofloxacin 500 mg PO twice daily while the outpatient cohort received IV ertapenem once daily. Broader spectrum antibiotics were provided for the outpatient cohort due to concerns for delayed onset of treatment if sepsis occurred, whereas the inpatient cohort would have closer monitoring and the ability to begin broad spectrum antibiotics at first signs of infection. With respect to growth factors, the outpatient group received a single dose of pegfilgrastim on day +1, whereas the inpatient group received daily filgrastim starting on day +5, until the ANC exceeded 500/μL for 2 consecutive days.

Study Endpoints

Neutrophil engraftment was defined as an ANC above 500/μL on 3 consecutive days. Platelet engraftment was defined as a platelet count greater than 20,000/μL without being sustained by transfusion. Grade 3 and 4 toxicities were recorded, using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0. For both cohorts, all hospitalizations were reviewed for length of stay and reason for admission. Unplanned admissions were defined as those that were not pre-arranged prior to initiation of the conditioning regimen. Clostridium difficile infections were reviewed and categorized as either first-time infections or re-activations. All deaths were reviewed and cause of death determined. Cases in which cause of death was not due to relapse were classified as non-relapse mortality, regardless of time from transplantation.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square and Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests were used to compare demographics and treatment-related risk factors. Exact Chi-square tests were used for comparisons involving small cell counts. Kaplan-Meier methods and log-rank tests were used to compare overall survival and progression-free survival probabilities, and cumulative incidence functions were used for non-relapse mortality, relapse/progression, ANC, and platelet engraftment to adjust for competing risks. Relapse/progression was the competing risk of non-relapse mortality; death was the competing risk for all other outcomes.

RESULTS

Patient, Disease, and Transplant Characteristics

A total of 230 patients were analyzed, 135 transplanted as inpatient and 95 as outpatient. In the inpatient cohort, 65.2% had myeloma and 34.8% lymphoma. In the outpatient cohort, 66.3% had myeloma and 33.7% had lymphoma. More than 90% of patients in both cohorts had chemo-sensitive disease at the time of transplant. There were no statistical differences in age, sex, primary disease, or disease status at the time of transplant (Table 1). However, in the inpatient cohort 26.7% of patients had a Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) of less than 80, compared to 6% in the outpatient cohort (p value < 0.001). Additionally, there was a trend toward a less favorable Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Comorbidity Index (HCT-CI) in the inpatient cohort with 53% of the patients having HCT-CI ≥ 3 vs. 40% in the outpatient cohort (p=0.06).

Patients in the inpatient cohort were more likely to receive dose reduced melphalan for conditioning (14.1% IP vs 6.4% OP) (Table 1). The majority of these patients received Mel 140 (12.6 % IP vs 1.1% OP; P value = 0.0008). Outpatient and inpatient received a similar CD34 cell dose (4.4 vs. 4.6 × 106/kg, respectively, p=0.581). Among the outpatients that were admitted, mean LOS was 5.4 days (3.9–6.9, 95% CI) versus 19.2 days in the inpatient cohort (18.6–19.8, 95% CI; p value of <0.0001).

Toxicities and Adverse Events

Grade 3 and 4 non-hematologic toxicities for each cohort are detailed in Table 2. Common toxicities included febrile neutropenia, bacteremia, Clostridium difficile infections, mucositis, diarrhea, central venous line complications and engraftment syndrome. No significant differences were evident between the outpatient and inpatient groups for any individual toxicity.

Table 2.

Grade 3–4 Toxicities and Adverse Events

| Inpatient (%) | Outpatient (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Toxicities | 1.000 | ||

| 0 | 96 (71.1) | 67 (70.5) | |

| 1 | 30 (22.2) | 22 (23.2) | |

| 2 | 5 (3.7) | 4 (4.2) | |

| 3 | 4 (3.0) | 2 (2.1) | |

| Diarrhea | 15 (11.1) | 14 (14.7) | 0.415 |

| Afib | 8 (5.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0.085 |

| Mucositis | 8 (5.9) | 6 (6.3) | 0.907 |

| HTN | 2 (1.5) | 3 (3.2) | 0.651 |

| CVL Complications | 0.545 | ||

| DVT | 9 (6.7) | 8 (8.4) | |

| Infection | 5 (3.7) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Revisions | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Febrile Neutropenia | 45 (33.6) | 28 (29.5) | 0.635 |

| Infections | 27 (20.0) | 18 (18.9) | 0.843 |

| C diff | 0.782 | ||

| Yes(any) | 16 (11.6) | 8 (8.4) | |

| New | 14 (10.4) | 7 (7.4) | |

| Reactivated | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Positive Blood Cx | 13 (9.6) | 9 (9.5) | 0.968 |

| Engraftment Syndrome | 31 (23.0) | 19 (20.0) | 0.592 |

| Total Unplanned Admits | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 120 (88.9) | 62 (65.3) | |

| 1 | 11 (8.1) | 24 (25.3) | |

| 2 | 3 (2.2) | 8 (8.4) | |

| 3 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.1) |

In both cohorts, a significant majority of patients experienced no grade 3 or 4 non-hematologic toxicities (71.1% IP vs 70.5% OP). Both groups had a similar percentage of patients who experienced >1 toxicity (Table 2). Overall, central venous catheter complications were low in both cohorts (11.1% IP vs 9.5% OP) and included deep vein thrombosis, infections, and need for line revisions. Only 1 patient in the outpatient cohort (1.1%) developed a central line associated blood stream infection compared to 5 patients in the inpatient cohort (3.7%)(P=NS). Febrile neutropenia and infections were significant toxicities in both cohorts. Febrile neutropenia occurred in 33.6% of inpatients compared to 29.5% of outpatients, with positive blood cultures in 9.6% of inpatients vs 9.5% of outpatients. Infections, including urine, blood and lung infections per chest imaging, were present in 20% of inpatients vs 18.9% of outpatients. The Clostridium difficile infection rate was similar in both groups (11.6% IP vs 8.4% OP) and no difference was seen in new or re-activation of prior infection. The incidence of grade 3–4 engraftment syndrome was similar in both cohorts, occurring in 23% of inpatients and 20% of outpatients. When analyzing the subset of patients with low (0–2) or high (>2) HCT-CI scores, there were no significant differences in the rates of grade III or grade IV complications, CVL complications, infections, or episodes of febrile neutropenia for those transplanted on an inpatient versus outpatient basis (data not shown).

There was a significant difference in the number of unplanned admissions, which were typically due to neutropenic fever, persistent diarrhea, inability to maintain adequate oral intake, uncontrolled pain, or hemodynamic instability. Owing to the fact that their transplant was started on an outpatient basis, the outpatient cohort had a significantly higher number of unplanned admissions (33 out of 95) versus the inpatient cohort (16 out of 135). Overall, 88.1% of inpatient and 65.3% of outpatient had no unplanned admissions (p value of <0.001). The outpatient cohort had 25.3% of patients with 1 unplanned admission, 8.4% with 2 unplanned admissions, and 1.1% with 3 unplanned admissions; compared to 8.1%, 2.2%, and 0.7%, respectively, of the inpatient cohort. Of the 33 patients in the OP cohort with unplanned admissions, 20 (60.6%) were in the pre-engraftment period, and 13 post-engraftment. For the IP cohort there were 16 unplanned admissions, all of which were post-engraftment since they were pursposely kept inpatient until engraftment. There was no statistical difference in rates of unplanned admissions between the two groups after engraftment (11.9% IP vs 13.7% OP, p=0.691). The rate of unplanned admissions decreased significantly over the latter part of the study, with 71.9% of outpatient having no unplanned admissions in 2012.

Transplant Outcomes

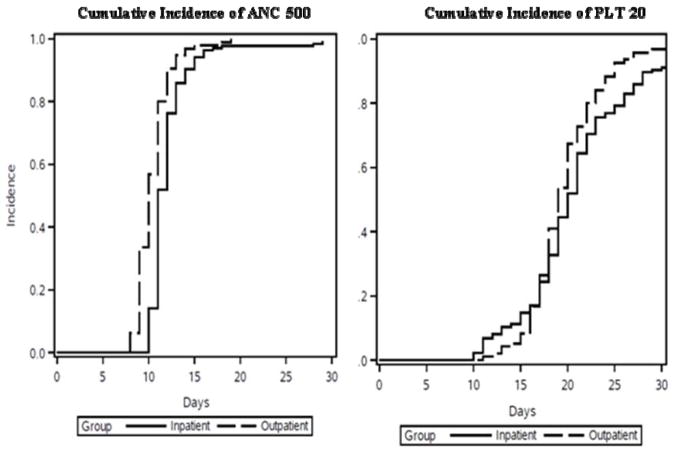

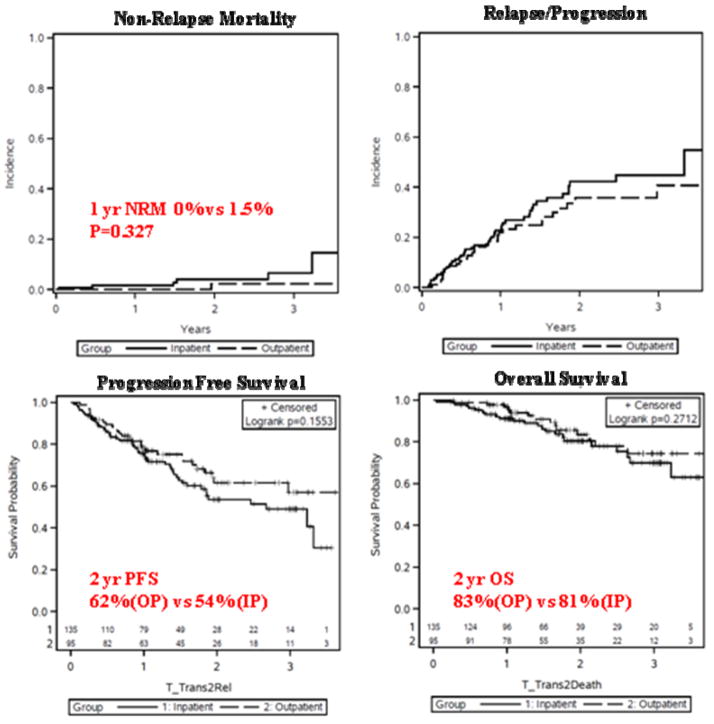

Supplemental Table 1 summarizes outcomes after transplantation for both cohorts. Hematopoietic recovery occurred earlier in the outpatient cohort, with median time to neutrophil recovery of 10 vs. 11 days (p<0.001) and median time to platelet recovery of 19 vs 20 days (p=0.053) (Figure 2). There were no statistically significant differences in non-relapse mortality, relapse or progression of disease, progression free survival, or overall survival between the two cohorts (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Earlier neutrophil engraftment was evident for those transplanted on an outpatient basis, in both low and high HCT-CI subgroups. However, mean days to platelet engraftment was significantly earlier for outpatients in the low HCT-CI group (19.3 OP vs 20.9 IP, p=0.037), but not in the high HCT-CI group (see supplemental Table 1).

Within the low and high HCT-CI groups, NRM, PFS, and OS were not statistically different between those transplanted on an inpatient versus outpatient basis (see Supplemental Table 1).

DISCUSSION

AutoHCT is well established as an important treatment option for patients with multiple myeloma and lymphoma. Historically, high dose therapy, AutoHCT, and the subsequent supportive care while awaiting hematopoietic recovery has been performed in an inpatient setting. However, with careful patient selection, outpatient AutoHCT can result in favorable outcomes for myeloma and lymphoma patients. Since 2009, our transplant program has offered a completely outpatient transplant experience to patients with favorable performance status, co-morbidity profile, expected compliance, and proximity to the cancer center. We sought to carefully study the toxicities, engraftment, non-relapse mortality, progression free survival, and overall survival in patients undergoing outpatient AutoHCT, in comparison to a contemporary group of patients managed on an inpatient basis by the same physician group.

In comparing the patient characteristics of the outpatient and inpatient groups, the outpatient group overall had more favorable KPS, and a trend toward lower HCT-CI scores (Table 1). Although HCT-CI was not formally used as a selection criterion for outpatient versus inpatient transplant, this difference was expected and is attributable to the careful selection of appropriate patients for outpatient AutoHCT. The higher use of reduced dose melphalan conditioning for the IPs reflects the higher prevalence of frailty and comorbidities in the inpatient group. However, there was considerable overlap in the clinical characteristics, including performance score and co-morbidities, of both groups.

Overall, there was no difference in the total number of specific or overall grade 3–4 non-hematologic toxicities between cohorts. This included central line related complications such as infections, thrombosis, and the need for revisions. Notably, there were no cases of non-relapse mortality in the outpatient cohort. This indicates that, with proper patient selection, high-dose melphalan and BEAM AutoHCT can be performed in an outpatient setting with a high degree of safety.

There were some important differences in clinical management of the two cohorts, primarily in the type of prophylactic antibiotic support given during severe neutropenia, and in type of hematopoietic growth factor. Our outpatient cohort received more aggressive prophylactic antibiotic support for neutropenia (ANC <500) with intravenous ertapenem as compared to oral ciprofloxacin in the inpatient cohort. This difference was a deliberate decision, due to the fact that the inpatients can be expeditiously switched to broad-spectrum IV antibiotic support as soon as fever develops. This would not be the case for a patient whose fever develops at home. In looking at antibiotic resistance post-transplant, only one patient in the OP cohort had evidence of emergence of a resistant organism, with admission for pneumonia secondary to a carbapenem-resistant pseudomonas 2 years after transplant. In addition, outpatients received a single dose of pegfilgrastim on day +1, while the inpatients received daily filgrastim starting on day +5. Despite the differences in antibiotic selection, G-CSF administration, and transplant environments, there were no differences in adverse outcomes such as febrile neutropenia, bacteremia, or Clostridium difficile infections between the outpatient and inpatient cohorts. It therefore remains uncertain whether more aggressive prophylactic intravenous antimicrobial therapy is, in fact, necessary for the outpatient group.

Hematopoietic recovery occurred earlier in the outpatient cohort for both neutrophils (10 vs. 11 days; p<0.001) and platelets (19 vs. 20 days; p=0.053). This was despite the fact that similar CD34 cell doses were infused. This may be attributable to the earlier administration of G-CSF in the outpatient cohort (day +1) versus the inpatient cohort (day +5), and/or due to the long-acting formulation (pegfilgrastim) given to the outpatient cohort. A previous study by Ferrara et al suggested that pegfilgrastim and filgrastim are equivalent in terms of safety and efficacy (15). However in that study, pegfilgrastim was given at a single dose on day +5 and filgrastim was started on day +2; median time to engraftment was similar. The earlier hematopoietic recovery in our study in the outpatient group suggests that day +1 administration of pegfilgrastim leads to earlier hematopoietic recovery.

Our study has several strengths. We have a large (n=230) sample size, using AutoHCT patients from a single transplant program, over a similar timeframe. We restricted our analysis to lymphoma and myeloma patients receiving BEAM or melphalan conditioning. We performed a careful and detailed analysis of toxicities encountered in both groups. Some of the prior studies of outpatient AutoHCT suffered from small sample sizes, a wide variety of disease types and conditioning regimens, lacked an inpatient comparison group, or had a limited analysis of toxicities (7, 16–18). In some previous studies, outpatient AutoHCT was not performed in a true outpatient setting, but in clinics set up within the inpatient unit (11, 17). At our institution, all transplant care for outpatient AutoHCT (including HDT, stem cell infusion, supportive care, etc) is performed in a separate outpatient center with a separate team of pharmacists, nurses and physicians. Additionally, patients do not reside in a building on the medical campus, but at their own home or in an unaffiliated hotel or with a family member or friend, within 30 miles of the medical center.

The main weaknesses of this study include its retrospective nature, the non-random nature of treatment assignment, and the fact that information regarding quality of life and cost/charges was not captured on all patients. We were able to perform a limited analysis of charges on 24 patients. We chose patients who had neutrophil engraftment within 3 days of the median and who had a typical transplant course. For patients transplanted on an inpatient basis, this meant they had a length of stay of 18–21 days without readmissions. For those transplanted on an outpatient basis, this meant they were never admitted. Within these parameters, we randomly selected 12 patients who underwent AutoHCT on an inpatient basis (6 BEAM and 6 Mel200), as well as 12 patients who underwent AutoHCT on an outpatient basis (6 BEAM and 6 Mel200). The outpatient BEAM patients had lower charges versus inpatient BEAM (mean $86,033 vs $141,649, p=0.0018). The outpatient Mel200 patients had lower mean charges than inpatient Mel200 patients ($79,988 vs $120,545, respectively), although this difference did not meet statistical significance (p=0.1773). This exploratory analysis suggests that outpatient AutoHCT may lead to a reduction in charges in the range of $40,000-$55,000. One study comparing outpatient AutoHCT to inpatient in multiple myeloma showed a cost savings of $19,522 Canadian dollars for those undergoing outpatient AutoHCT (19). Jagannath et al confirmed cost savings in the outpatient setting, due to lower pharmacy, hospitalization and pathology/laboratory charges (14). In terms of out of pocket costs to the patient, a prior study by Rizzo et al showed no significant difference for outpatient versus inpatient AutoHCT (20). An important area that requires additional study is the impact of transplant setting on quality of life. This is an issue not only for the patient but for family members since outpatient transplant requires a family member or close friend to take responsibility for the patient when he or she is not at the medical center (8, 21).

We conclude that, with careful patient selection and minor modifications to the management of neutropenia, a fully outpatient AutoHCT program can be successful. Our coordinated approach has been associated with minimal non-relapse mortality, excellent hematopoietic recovery, and acceptable toxicity in lymphoma and myeloma patients undergoing BEAM and melphalan AutoHCT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the nursing staff, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, medical residents and hematology/oncology fellows who helped care for these patients on both the inpatient and outpatient transplant units, Jean Esselmann for transplant coordination, and Charles Zhao for database support.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relevant to the content of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, Somers R, Van der Lelie H, Bron D, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995 Dec 7;333(23):1540–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geisler CH. Autologous transplantation and management of younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2012 Jun;25(2):211–20. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmitz N, Pfistner B, Sextro M, Sieber M, Carella AM, Haenel M, et al. Aggressive conventional chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed chemosensitive hodgkin’s disease: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2002 Jun 15;359(9323):2065–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08938-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schouten HC, Qian W, Kvaloy S, Porcellini A, Hagberg H, Johnsen HE, et al. High-dose therapy improves progression-free survival and survival in relapsed follicular non-hodgkin’s lymphoma: Results from the randomized european CUP trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Nov 1;21(21):3918–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Child JA, Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Owen RG, Bell SE, Hawkins K, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem-cell rescue for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 08;348(19):1875–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022340. 2014/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attal M, Harousseau J, Stoppa A, Sotto J, Fuzibet J, Rossi J, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of autologous bone marrow transplantation and chemotherapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 1996 Jul 11;335(2):91–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607113350204. 2014/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leger C, Sabloff M, McDiarmid S, Bence-Bruckler I, Atkins H, Bredeson C, et al. Outpatient autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2006 Oct;85(10):723–9. doi: 10.1007/s00277-006-0149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frey P, Stinson T, Siston A, Knight SJ, Ferdman E, Traynor A, et al. Lack of caregivers limits use of outpatient hematopoietic stem cell transplant program. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002 Dec;30(11):741–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meisenberg BR, Ferran K, Hollenbach K, Brehm T, Jollon J, Piro LD. Reduced charges and costs associated with outpatient autologous stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998 May;21(9):927–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gluck S, des Rochers C, Cano C, Dorreen M, Germond C, Gill K, et al. High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous blood cell transplantation: A safe and effective outpatient approach. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997 Sep;20(6):431–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDiarmid S, Hutton B, Atkins H, Bence-Bruckler I, Bredeson C, Sabri E, et al. Performing allogeneic and autologous hematopoietic SCT in the outpatient setting: Effects on infectious complications and early transplant outcomes. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010 Jul;45(7):1220–6. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulmeister L, Quiett K, Mayer K. Quality of life, quality of care, and patient satisfaction: Perceptions of patients undergoing outpatient autologous stem cell transplantation. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005 Jan 19;32(1):57–67. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.57-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JH, Goulston C, Zangari M, Tricot G, Boyer MW, Hanson KE. Impact of a change in antibacterial prophylaxis on bacteremia and hospitalization rates following outpatient autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Transplant Infectious Disease. 2014 doi: 10.1111/tid.12225. n/a,n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jagannath S, Vesole DH, Zhang M, Desikan KR, Copeland N, Jagannath M, et al. Feasibility and cost-effectiveness of outpatient autotransplants in multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997 Sep;20(6):445–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrara F, Izzo T, Criscuolo C, Riccardi C, Viola A, Delia R, et al. Comparison of fixed dose pegfilgrastim and daily filgrastim after autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma autografted on a outpatient basis. Hematol Oncol. 2011 Sep;29(3):139–43. doi: 10.1002/hon.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrara F, Palmieri S, Viola A, Copia C, Schiavone EM, De Simone M, et al. Outpatient-based peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for patients with multiple myeloma. Hematol J. 2004;5(3):222–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meisenberg BR, Miller WE, McMillan R, Callaghan M, Sloan C, Brehm T, et al. Outpatient high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell rescue for hematologic and nonhematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1997 Jan;15(1):11–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman B, Brauneis D, Seldin DC, Quillen K, Sloan JM, Renteria AS, et al. Hospital admissions following outpatient administration of high-dose melphalan and autologous SCT for AL amyloidosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(10):1345–6. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.132. print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holbro A, Ahmad I, Cohen S, Roy J, Lachance S, Chagnon M, et al. Safety and cost-effectiveness of outpatient autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013 Apr;19(4):547–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rizzo JD, Vogelsang GB, Krumm S, Frink B, Mock V, Bass EB. Outpatient-based bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies: Cost saving or cost shifting? J Clin Oncol. 1999 Sep;17(9):2811–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonald JC, Stetz KM, Compton K. Educational interventions for family caregivers during marrow transplantation. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996 Oct;23(9):1432–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.