Abstract

Background

For low-risk prostate cancer (PCa), active surveillance (AS) may confer comparable oncological outcomes to radical prostatectomy (RP). Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) outcomes are important to consider, yet few studies have examined HRQoL for patients managed with AS. This study compared longitudinal HRQoL in a prospective, racially diverse, and contemporary cohort of patients who underwent RP or AS for low-risk PCa.

Methods

Beginning in 2007, HRQoL data from validated questionnaires (EPIC and SF-36) were collected by the Center for Prostate Disease Research in a multi-center national database. Patients aged ≤75 that were diagnosed with low-risk PCa and elected RP or AS for initial disease management were followed for three years. Mean scores were estimated using generalized estimating equations, adjusting for baseline HRQoL, demographic and clinical patient characteristics.

Results

Of the patients with low-risk PCa, 228 underwent RP and 77 underwent AS. Multivariable analysis revealed that RP patients had significantly worse sexual function, sexual bother, and urinary function at all time points compared to patients on AS. Differences in mental health between groups were below the threshold for clinical significance at one year.

Conclusions

This study found no differences in mental health outcomes but worse urinary and sexual HRQoL for RP patients compared to AS patients for up to three years. These data offer support for management of low risk PCa with AS as a means for postponing the morbidity associated with RP without concomitant mental health declines.

Keywords: Active surveillance, Prostate cancer, Quality of life, Radical prostatectomy, Survivorship

BACKGROUND

Over-treatment of early-stage prostate cancer (PCa) has prompted significant changes in recommendations for treatment.1 Current guidelines suggest delaying therapy with curative intent for patients deemed “very low-” and “low-” risk, as defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.2 This management strategy, referred to as active surveillance (AS), may confer adequate and comparable oncological outcomes to definitive therapy.3 Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) outcomes are therefore important to consider when deciding on an approach to minimize both the physical and psychological burden of the disease and its treatment.4

To help patients weigh the costs and benefits of PCa management strategies, studies that examine the impact of treatment choice on short- and long-term HRQoL are warranted. Patients managed with AS may be spared some of the decline in physical HRQoL compared to patients receiving definitive treatments such as radical prostatectomy (RP), but could concomitantly suffer greater mental health declines due to the anxiety of delaying therapy.5 While prior studies have examined HRQoL outcomes following definitive treatments for PCa,6–8 few have focused on patients managed on AS or compared patients who delay therapy to those selecting definitive therapy.9, 10

This study assessed the impact of PCa management strategy on disease-specific and general HRQoL outcomes over time in a prospective, racially diverse, and contemporary cohort of low-risk PCa patients counseled via multi-disciplinary clinics. Patients who selected RP were compared to those managed with AS over a three-year period.

METHODS

Study Population

All patients were enrolled in the Center for Prostate Disease Research (CPDR) Multi-Center National Database, which contains demographic, clinical, treatment and outcomes data. Informed consent was obtained at the time of transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy for suspicion of PCa, as described previously.11 Prospective collection of HRQoL data was IRB-approved and initiated in 2007. Sites included Madigan Army Medical Center (Tacoma, WA), Naval Medical Center (San Diego, CA), Virginia Mason (Seattle, WA), and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, MD). Site participation in the CPDR database was granted by each institutional IRB, with second-tier IRB approval by the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

Survey Instruments

HRQoL data were captured using two validated questionnaires, the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) and the 36-item RAND Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36) survey.12–14 EPIC measures paired subscales evaluating function and bother for urinary, sexual, bowel, and hormonal domains. Higher scores indicate better HRQoL (range 0–100). SF-36 measures eight subscales that combine into physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores. Surveys were administered immediately prior to or following biopsy (baseline) and at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months.

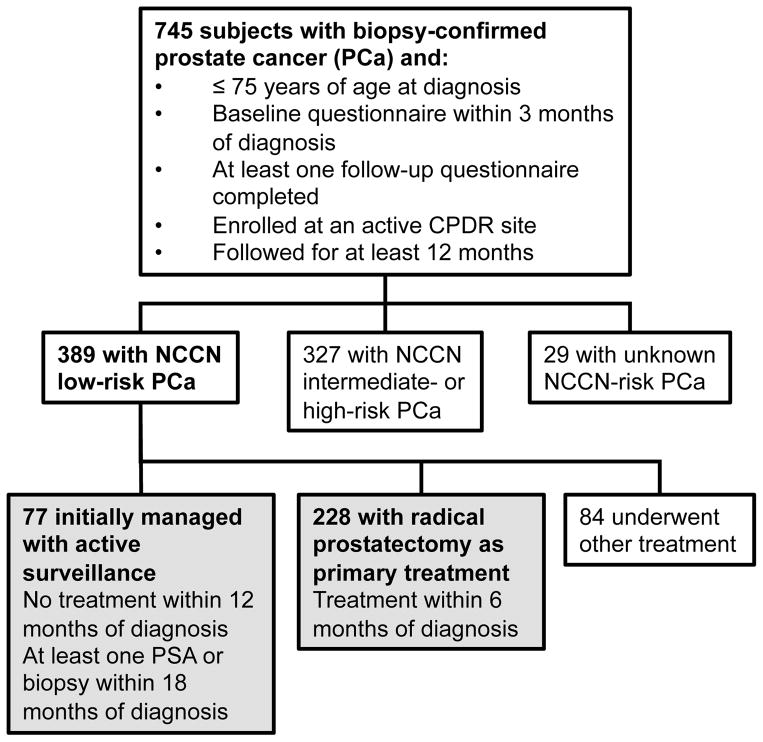

Eligibility criteria included biopsy-confirmed PCa diagnosed at age ≤75 years, completion of baseline and at least one follow-up survey, and patient follow up for a minimum of 12 months (Figure 1). The study sample was restricted to patients diagnosed with “low-risk” PCa, defined as clinical stage T1-T2a, biopsy Gleason score ≤6, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) <10 ng/mL.15 Comorbidity included a count of up to eight conditions: lung disease, heart disease, hypertension, cerebral vascular accident, diabetes, elevated cholesterol, prostatitis, and renal insufficiency.

Figure 1. Inclusion criteria and sample size for study.

Of the 745 prostate cancer patients meeting initial inclusion criteria, 389 (52%) had low-risk disease. Among these, 77 (19.8%) underwent active surveillance, and 228 (58.6%) underwent radical prostatectomy within 6 months of PCa diagnosis. All analyses focused on these two patient cohorts, shown in gray above.

Patients who underwent RP within six months of diagnosis were compared to those managed with AS. Patients on AS received no definitive treatment within one year of diagnosis and had either AS noted as the management strategy in their medical record or at least one PSA or repeat biopsy within 18 months. Treatments received subsequent to meeting these definitions were considered secondary.

Statistical Analysis

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and baseline HRQoL scores were compared between treatment cohorts using Welch’s t-tests for continuous variables, Chi-square tests for categorical variables, and Cochran-Armitage tests for ordinal variables. For the primary study aim comparing differences across treatment groups over time, mean scores were estimated using generalized estimating equations (GEE), with autoregressive working correlation and sandwich variance estimators.16 Time-point was included as a categorical covariate. Other covariates included treatment, time-by-treatment interactions, mean-centered baseline age and HRQoL, race/ethnicity, and number of comorbidities (0, 1, ≥2). Adjusted mean scores per treatment group and time-point were estimated for patients of mean age and baseline HRQoL at the reference level of the other covariates.

The secondary study aim examined absolute change from baseline for each treatment group using GEE models with change from baseline score as the outcome variable. To distinguish clinically meaningful from statistically significant differences, in the absence of an anchor-based evaluation for each subscale score, the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) was calculated as 0.5 baseline score standard deviations for each cohort. Equivalence was demonstrated when the entire 95% confidence interval for the adjusted mean difference or change was within the range of –MCID to +MCID.17 Patients were censored at the date of secondary treatment, if any.

Patients in the RP cohort who had not yet undergone RP before completing their 3- and 6-month surveys were excluded from analyses of those time-points. Two sensitivity analyses were conducted: one including all surveys from patients receiving secondary treatment and one with missing follow-up scores imputed using multiple imputation. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p-values were adjusted for multiple time-points by Bonferroni’s method. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Of the 745 patients meeting initial eligibility criteria, 389 (52%) had low-risk PCa. Among those, 228 (59%) underwent RP and 77 (20%) were managed with AS (Figure 1). The remaining 84 patients selected other primary treatment modalities and were excluded.

Mean age at diagnosis was 58 and 65 years for patients treated with RP and AS, respectively (p<0.0001) (Table 1). On average, 2.8 months elapsed between diagnosis and RP. There were differences in site of enrollment and months of follow-up (p=0.0001). At baseline, the AS cohort reported lower sexual function and bother scores (p=0.002 and p=0.03, respectively) (Table 2). No other statistically significant differences in baseline HRQoL scores were observed.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

| Active Surveillance (N=77) | Radical Prostatectomy (N=228) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean ±SD (range) | 65 ±8.1 (45–75) | 58 ±7.4 (40–74) | <0.0001 |

| PSA at diagnosis, ng/mL | |||

| Mean ±SD (range) | 4.0 ±1.9 (0.3–9.2) | 4.2 ±1.9 (0.2–10) | 0.56 |

| Months to primary treatment | |||

| Mean ±SD (range) | NA | 2.8 ±1.1 (0.5–5.8) | |

| Months to secondary treatment | |||

| N (%) | 11 (14) | 11 (5) | |

| Mean ±SD (range) | 24 ±14 (14–62) | 16 ±8.5 (6.3–30) | 0.11 |

| Months follow-up | |||

| Mean ±SD (range) | 27 ±17 (3.0–60) | 36 ±17 (3.0–60) | 0.0001 |

| Clinical stage, N (%) | |||

| T1a-T1c | 50 (65) | 161 (71) | |

| T2a | 27 (35) | 67 (29) | 0.35 |

| Comorbidities, N (%) | |||

| 0 | 17 (22) | 56 (25) | |

| 1 | 21 (27) | 86 (38) | |

| ≥2 | 39 (51) | 86 (38) | 0.14 |

| TRUS biopsies prior to baseline, N (%) | |||

| 0 | 69 (90) | 212 (93) | |

| ≥1 | 8 (10) | 16 (7) | 0.34 |

| Race/Ethnicity, N (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 61 (79) | 163 (71) | |

| African American | 13 (17) | 45 (20) | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 9 (4) | |

| Asian | 2 (3) | 10 (4) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 1 (0) | 0.27 |

| Site, N (%) | |||

| MAMC | 10 (13) | 23 (10) | |

| NMCSD | 21 (27) | 46 (20) | |

| VM | 22 (29) | 26 (11) | |

| WRNMMC | 24 (31) | 133 (58) | 0.0001 |

MAMC, Madigan Army Medical Center; NMCSD, Naval Medical Center San Diego; VM, Virginia Mason; WRNMMC, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline HRQoL scores

| HRQoL Subscale | Active Surveillance (Mean ±SD) | Radical Prostatectomy (Mean ±SD) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPIC | |||

| Urinary Function | 93 ±10 | 95 ±10 | 0.36 |

| Urinary Bother | 84 ±14 | 85 ±16 | 0.62 |

| Sexual Function | 51 ±26 | 62 ±22 | 0.002 |

| Sexual Bother | 70 ±29 | 79 ±29 | 0.03 |

| Bowel Function | 94 ±8 | 93 ±8 | 0.49 |

| Bowel Bother | 96 ±7 | 94 ±11 | 0.26 |

| Hormonal Function | 91 ±10 | 91 ±11 | 0.91 |

| Hormonal Bother | 95 ±8 | 95 ±9 | 0.88 |

| SF-36 | |||

| PCS | 55 ±5 | 56 ±6 | 0.33 |

| MCS | 55 ±6 | 56 ±6 | 0.35 |

PCS, Physical Component Summary; MCS, Mental Component Summary

Survey completion patterns were examined over time (Supplementary Table 1). At 36 months, the survey completion remained high for the AS and RP cohorts at 72% and 60%, respectively. Patients in both treatment groups completed 5 HRQoL surveys, on average. Eleven patients in each group were censored on the date of secondary treatment, including 5 AS patients who went on to receive RP.

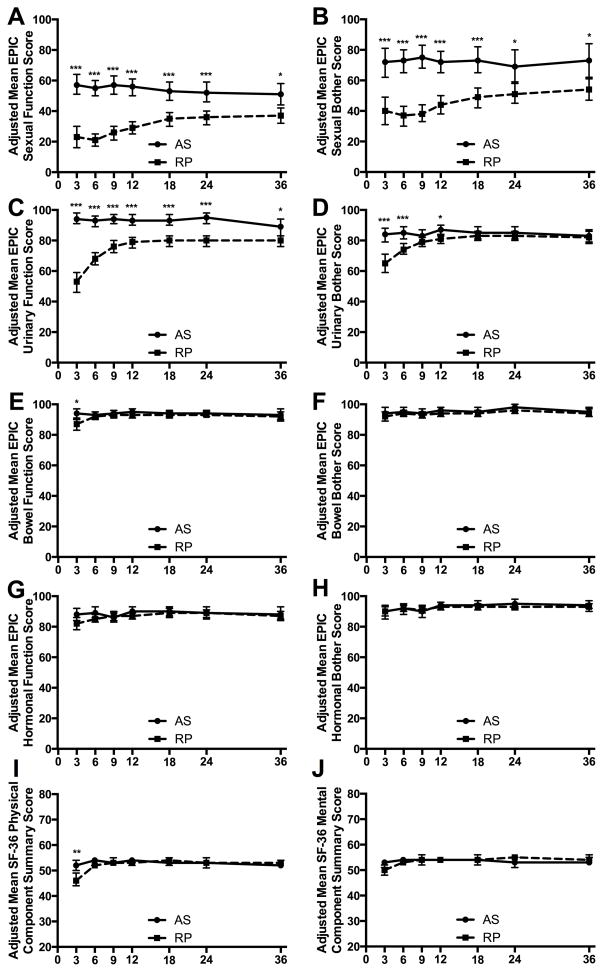

HRQoL associated with Sexual Symptoms

Adjusted mean sexual function and bother scores were lower for RP patients at all follow-up time points (Figures 2A&B). In the RP cohort, sexual function and bother scores improved after 6 months, stabilized by 2 years, but remained significantly lower than those for AS patients at 3 years (p=0.01 and p=0.049, respectively, Table 3).

Figure 2. Adjusted mean EPIC and SF-36 scores for patients managed on active surveillance compared to those treated with radical prostatectomy.

Means from the multivariable model fitted with GEE, adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, and baseline HRQoL scores. Means are for a patient with average age, baseline score, at the reference level of the other covariates (Caucasian, ≥2 comorbidities). Bars represent 95% confidence intervals, and asterisks indicate statistical significance after adjustment for the number of time points (7) using the Bonferroni correction. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. The solid line indicates data from the active surveillance (AS) cohort and the dashed line indicates data from the radical prostatectomy (RP) cohort.

Table 3.

Adjusted mean differencesa in HRQoL scores between radical prostatectomy and active surveillance patients

| 1-Year Difference (RP-AS) | 2-Year Difference (RP-AS) | 3-Year Difference (RP-AS) | MCIDc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| HRQoL Subscale | Mean (95% CI) | p-valueb | Mean (95% CI) | p-valueb | Mean (95% CI) | p-valueb | |

| EPIC | |||||||

| Sexual Function | −27 (−32, −22) | <0.0001 | −17 (−23, −10) | 0.0005 | −14 (−21, −7) | 0.01 | 11 |

| Sexual Bother | −29 (−36, −21) | <0.0001 | −18 (−29, −7) | 0.03 | −19 (−31, −7) | 0.049 | 14 |

| Urinary Function | −14 (−18, −11) | <0.0001 | −15 (−19, −11) | <0.0001 | −9 (−15, −3) | 0.046 | 5 |

| Urinary Bother | −5 (−9, − −2) | 0.04 | −2 (−6, 2) | 1 | −1 (−6, 5) | 1 | 8 |

| Bowel Function | −3 (−5, −1) | 0.06 | −1 (−3, 1) c | 1 | −1 (−5, 4) | 1 | 4 |

| Bowel Bother | −2 (−4, 0) c | 0.74 | −2 (−4, 1) c | 1 | −1 (−5, 3) | 1 | 5 |

| Hormonal Function | −3 (− −6, 1) | 0.96 | −1 (−5, 4) | 1 | −1 (−6, 4) | 1 | 5 |

| Hormonal Bother | −1 (−4, 2) | 1 | −2 (−6, 1) | 1 | −2 (−5, 1) | 1 | 4 |

| SF-36 | |||||||

| PCS | −1 (−2, 1) c | 1 | 0 (−2, 2) c | 1 | 0 (−2, 3) | 1 | 3 |

| MCS | 0 (−1, 1) c | 1 | 2 (0, 4) | 0.60 | 1 (−1, 3) | 1 | 3 |

RP, Radical Prostatectomy; AS, Active Surveillance; CI, Confidence Interval; PCS, Physical Component Summary; MCS, Mental Component Summary; MCID, Minimal Clinically Important Difference

Mean differences estimated from multivariable GEE model and adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, and baseline HRQoL

p-values adjusted for number of time points (7) using Bonferroni

Equivalence was demonstrated when entire 95% CI was within range of - MCID to +MCID.

HRQoL associated with Urinary Symptoms

Compared to those on AS, RP patients reported significantly poorer urinary function at all follow-up time points (Figure 2C). Urinary function scores recovered between 3 and 12 months in the RP cohort but remained lower than in the AS cohort at 3 years (p=0.046, Table 3). Urinary bother scores were significantly lower in the RP cohort at 3, 6, and 12 months (Figure 2D). RP cohort urinary bother scores recovered by 18 months and were equivalent to AS scores at 2 and 3 years (Table 3).

HRQoL associated with Bowel and Hormonal Symptoms

RP patients reported worse bowel function at 3 months than patients on AS. No other statistically significant differences in bowel function or bother were observed between cohorts; bowel function was equivalent at 2-years and bother was equivalent at 1 and 2 years (Figures 2E&F, Table 3). In addition, no statistically significant differences in hormonal function or bother were observed between cohorts at any time point (Figures 2G&H, Table 3).

General HRQoL

RP patients exhibited significantly lower SF-36 PCS scores at 3 months compared to those on AS (Figure 2I). Of the four subscales that constitute the PCS, the RP cohort had significantly lower mean scores in Physical Functioning at 3 months and Role-Physical at 3 and 6 months (Supplementary Figures 2A&B). After 6 months, no significant differences in PCS or individual physical health subscale scores were observed and PCS was equivalent at 1 and 2 years (Table 3).

No significant differences in MCS scores were observed between cohorts at any time point (Figure 2J, Table 3) and MCS was equivalent at 1 year. Of the four subscales that constitute the MCS, the RP cohort displayed significantly lower mean scores in Social Functioning at 3 and 6 months. No other differences in mental health subscale scores were observed (Supplementary Figure 2).

When the analyses were repeated to include patients receiving secondary treatment (Supplementary Table 2) and missing data using imputation (Supplementary Table 3), similar findings were observed. Sexual and urinary function scores remained significantly lower in the RP cohort at 2 and 3 years, and sexual bother scores remained significantly lower at 1 year. Other differences between cohorts did not retain statistical significance, but the magnitude of the adjusted mean differences was comparable for all time points and subscales.

Change in HRQoL from Baseline

Table 4 provides adjusted mean absolute change scores from baseline to 1-, 2-, and 3-years post-diagnosis for each subscale and cohort. In the AS cohort, there were no statistically significant and clinically meaningful declines in HRQoL. The only statistically significant change from baseline in the AS cohort was a decline in the SF-36 PCS score at 3-years (−3, 95% CI -5 to −1), but this decline was not greater than the MCID. In contrast, the RP cohort experienced clinically meaningful and statistically significant declines in sexual function, sexual bother, and urinary function scores that persisted for 3 years.

Table 4.

Adjusted mean absolute changea in HRQoL scores from baseline

| 1-Year Change | 2-Year Change | 3-Year Change | MCID | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Treatment and HRQoL Subscale | Mean (95% CI) | p-valueb | Mean (95% CI) | p-valueb | Mean (95% CI) | p-valueb | |

| Active Surveillance | |||||||

| EPIC | |||||||

| Sexual Function | −2 (−7, 4) c | 1 | −4 (−11, 2) c | 1 | −6 (−14, 2) | 0.89 | 13 |

| Sexual Bother | −3 (−11, 5) c | 1 | −6 (−17, 6) | 1 | −5 (−17, 7) | 1 | 15 |

| Urinary Function | −1 (−4, 3) c | 1 | 1 (−3, 5) | 1 | −5 (−11, 1) | 0.64 | 5 |

| Urinary Bother | 2 (− −3, 6) c | 1 | 1 (−4, 5) c | 1 | −2 (−7, 4) | 1 | 7 |

| Bowel Function | 2 (−1, 4) | 1 | 0 (−2, 3) c | 1 | −1 (−6, 4) | 1 | 4 |

| Bowel Bother | 1 (−2, 3) | 1 | 2 (−1, 4) | 1 | −1 (−4, 3) | 1 | 3 |

| Hormonal Function | −2 (−5, 2) | 1 | −2 (−6, 2) | 1 | −3 (−8, 2) | 1 | 5 |

| Hormonal Bother | −1 (−4, 1) | 1 | 0 (−3, 3) c | 1 | 0 (−3, 2) c | 1 | 4 |

| SF-36 | |||||||

| PCS | −1 (−3, 0) | 0.36 | −2 (−4, 0) | 0.21 | −3 (−5, −1) | 0.04 | 3 |

| MCS | −1 (−3, 0) | 0.46 | −2 (−4, 0) | 0.11 | − −2 (−4, 0) | 0.48 | 3 |

| Radical Prostatectomy | |||||||

| EPIC | |||||||

| Sexual Function | −31 (−36, −26) | <0.0001 | − −24 (−29, −19) | <0.0001 | −23 (−28, −17) | <0.0001 | 11 |

| Sexual Bother | −34 (−41, −27) | <0.0001 | −26 (−33, −19) | <0.0001 | −24 (−32, −17) | <0.0001 | 14 |

| Urinary Function | −15 (−19, −11) | <0.0001 | −14 (−18, −11) | <0.0001 | −15 (−19, −11) | <0.0001 | 5 |

| Urinary Bother | −2 (−6, 1) c | 1 | 0 (−4, 3) c | 1 | −1 (− −5, 3) c | 1 | 8 |

| Bowel Function | −1 (−3, 1) c | 1 | 0 (−2, 2) c | 1 | −1 (−4, 1) | 1 | 4 |

| Bowel Bother | 0 (−3, 2) c | 1 | 1 (−1, 4) c | 1 | 0 (−3, 3) c | 1 | 5 |

| Hormonal Function | −4 (−7, −1) | 0.03 | −2 (−5, 1) c | 1 | −4 (−6, −1) | 0.04 | 6 |

| Hormonal Bother | −2 (−4, 1) c | 1 | −1 (−4, 1) c | 1 | −1 (−4, 1) c | 1 | 5 |

| SF-36 | |||||||

| PCS | −2 (−3, −1) | 0.02 | −2 (−3, 0) | 0.11 | −2 (−4, −1) | 0.01 | 3 |

| MCS | −1 (−2, 0) c | 0.15 | −1 (−2, 1) c | 1 | −1 (−2, 0) c | 0.81 | 3 |

CI, Confidence Interval; PCS, Physical Component Summary; MCS, Mental Component Summary; MCID, Minimal Clinically Important Difference

Absolute change computed as 1-, 2-, or 3-year score minus baseline score. Estimates for patient with average age at reference level of other covariates (Caucasian, ≥2 comorbidities)

p-values adjusted for number of time points (7) using Bonferroni correction.

Equivalence was demonstrated when entire 95% CI was within range of -MCID to +MCID.

DISCUSSION

In the U.S., use of AS for low-risk PCa rose from 9.7% in 2004 to 15.3% in 2007 according to SEER and Medicare data.18 A recent nation-wide survey revealed that surveillance strategies are accepted by clinicians but largely underutilized, as only 22.1% of urologists and radio-oncologists would currently recommend AS for low-risk PCa.19 The relative paucity of prospective data on long-term follow-up of HRQoL outcomes in PCa cohorts makes the decision regarding treatment choice even more difficult for patients. To better understand the consequences of choosing AS, this study assessed HRQoL changes across time in patients with low-risk PCa managed with AS or RP. Notably, AS patients were spared the declines in urinary and sexual function experienced by the RP cohort without suffering concomitant declines in mental HRQoL.

While several studies have examined the effects of different PCa treatment modalities on HRQoL outcomes, few have prospectively compared RP versus AS or watchful waiting (WW).20, 21 A randomized clinical trial of RP and WW patients found that the prevalence of erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence was higher in the RP cohort.21 In another prospective study, patients treated with RP showed worse urinary and erectile function, and urinary continence than those managed with WW after one year.22 A recent Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor (CaPSURE) study compared longitudinal HRQoL among various treatment modalities and a combined AS/WW group and found that surgery had the largest impact on sexual function and bother and urinary function.23 The current study confirms that these conclusions hold when examined in a low-risk cohort of RP versus strictly AS patients.

Our finding that RP and AS patients exhibit comparable mental health outcomes is consistent with prior population-based studies, which showed no significant changes in MCS scores between AS and RP cohorts at 3 years24 or between RP and WW cohorts at five to ten years,25 and a randomized trial, which found no difference in prevalence of anxiety or depressed mood between RP and WW cohorts after 12 years.10 In addition, this study found no significant change from baseline mental health for those managed on AS throughout the three-year study period. This is supported by a previous study in which Finnish men on AS reported less general anxiety 18 months following diagnosis26 and did not display loss of mental HRQoL after one year compared to the general population.27 This is an important finding given concerns that patients who delay treatment may experience short-term or lasting reductions in mental health

The present study is one of the first to report on longitudinal HRQoL in a carefully defined, prospective cohort of AS patients. A rigorous AS definition was implemented to help distinguish AS patients from those choosing WW. Moreover, all patients enrolled in this study attended a CPDR multi-disciplinary clinic, with radiation and medical oncologists, urologic surgeons, and nurse practitioners, to receive balanced and tailored counseling on their treatment options. This setting is an important study strength, as the multi-disciplinary approach is becoming increasingly utilized among medical centers providing treatment for PCa.28

In this cohort, 14% of AS and 5% of RP patients went on to receive secondary treatment after a mean of 24 and 16 months, respectively. Exclusion of these patients does not appear to have biased our results; when the analyses were repeated without censoring, overall study conclusions were unaltered. Future studies should examine HRQoL of patients receiving secondary treatment after initial AS, as they may experience worse post-treatment HRQoL than those who undergo definitive treatment immediately.29

Other study strengths include the racial diversity of the cohort, use of validated HRQoL metrics, and adjustment of follow up data for baseline scores and clinical characteristics. Additionally, MCIDs were presented for each subscale, allowing for a practical interpretation of observed differences in scores. HRQoL score differences can be difficult to interpret, as statistically significant differences are not always clinically meaningful.30 Consideration of MCIDs is therefore paramount for HRQoL results to be interpretable for both clinicians and patients.

Since patients were self-selected and not randomized into treatment groups, it is possible that patients electing AS may have been less anxious than those choosing to undergo immediate curative therapy. However, no significant differences were observed in mental health scores between the RP and AS cohorts at baseline. Randomized controlled trials such as the ProtecT trial31 will be able to test whether the study conclusions hold in the absence of any selection biases, but such studies are considered unfeasible in the US. This prospective cohort design is the most rigorous design possible.

Another limitation of the study was the small sample size of the AS cohort, particularly at the later time points. Declines in sample size were due to administrative censoring, conversion to secondary treatment, and missing data. Despite the sample size and conservative adjustment for multiple comparisons, several statistically significant differences persisted at 3 years follow-up. To assess the effect of missing data, missing HRQoL scores for patients with sufficient follow-up were imputed in a separate sensitivity analysis. This analysis yielded similar results, suggesting that missing data did not meaningfully influence the results. However, missing data could have still introduced bias, and future studies will be needed to confirm our findings.

In this study, it was not possible to address erectile aid use or other lifestyle changes that might impact HRQoL.32 However, the use of such aids is widespread in the US and is unlikely to differ between patients choosing AS versus RP.33 The generalizability of our findings may also be limited given our strict eligibility criteria and unique cohort features. For instance, our results may not apply to all healthcare systems since patients were enrolled at United States medical facilities and the majority of patients were military health care beneficiaries. However, the multi-institutional and contemporary nature of our cohort overcomes several of these limitations when compared to single institution reports and historical WW series. Ultimately, patient preference remains a central consideration in treatment decision-making, and the findings from this study can help inform and direct that choice.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found no differences in mental health outcomes but worse urinary and sexual HRQoL for up to three years in patients undergoing surgery for low-risk prostate cancer compared to those on active surveillance. These data offer support for management of low risk prostate cancer with active surveillance as a means for postponing the morbidity associated with radical prostatectomy without concomitant mental health declines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was funded through the Center for Prostate Disease Research and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sci-ences. Contributions by K.O.-D. were supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR000423).

We would like to thank the patients who participated in this study, the CPDR data managers for their contributions, and Ms. Deborah Sparks for providing IRB support.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Meng MV, Mehta SS, Carroll PR. The changing face of low-risk prostate cancer: trends in clinical presentation and primary management. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2141–2149. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aizer AA, Paly JJ, Zietman AL, et al. Models of care and NCCN guideline adherence in very-low-risk prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:1364–1372. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klotz L, Zhang L, Lam A, Nam R, Mamedov A, Loblaw A. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large, active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:126–131. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright JL, Lin DW, Cowan JE, Carroll PR, Litwin MS, Ca PI. Quality of life in young men after radical prostatectomy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2008;11:67–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilcox CB, Gilbourd D, Louie-Johnsun M. Anxiety and health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients undergoing active surveillance of prostate cancer in an Australian centre. BJU Int. 2014;113:64–68. doi: 10.1111/bju.12557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, et al. 5-year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Urol. 2005;173:1701–1705. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154637.38262.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan KH, et al. Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes JH, Ollendorf DA, Pearson SD, et al. Active surveillance compared with initial treatment for men with low-risk prostate cancer: a decision analysis. JAMA. 2010;304:2373–2380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson E, Steineck G, Holmberg L, et al. Long-term quality-of-life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:891–899. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brassell SA, Dobi A, Petrovics G, Srivastava S, McLeod D. The Center for Prostate Disease Research (CPDR): a multidisciplinary approach to translational research. Urol Oncol. 2009;27:562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56:899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware JEJ. SF-36 Health Survey Update. Spine. 2000;25:3130–3139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305:160–164. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Comprehensive Cancer Network N. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer: V3.2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filson CP, Schroeck FR, Ye Z, Wei JT, Hollenbeck BK, Miller DC. Variation in Use of Active Surveillance among Men Undergoing Expectant Treatment for Early Stage Prostate Cancer. J Urol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SP, Gross CP, Nguyen PL, et al. Perceptions of Active Surveillance and Treatment Recommendations for Low-risk Prostate Cancer: Results from a National Survey of Radiation Oncologists and Urologists. Med Care. 2014;52:579–585. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergman J, Litwin MS. Quality of life in men undergoing active surveillance for localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012:242–249. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:790–796. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siston AK, Knight SJ, Slimack NP, et al. Quality of life after a diagnosis of prostate cancer among men of lower socioeconomic status: results from the Veterans Affairs Cancer of the Prostate Outcomes Study. Urology. 2003;61:172–178. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Punnen S, Cowan JE, Chan JM, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR. Long-term Health-related Quality of Life After Primary Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer: Results from the CaPSURE Registry. Eur Urol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith DP, King MT, Egger S, et al. Quality of life three years after diagnosis of localised prostate cancer: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4817. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV, Vingerhoets AJ, et al. Long-term quality of life among Dutch prostate cancer survivors: results of a population-based study. Cancer. 2006;107:2186–2196. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venderbos LD, van den Bergh RC, Roobol MJ, et al. A longitudinal study on the impact of active surveillance for prostate cancer on anxiety and distress levels. Psychooncology. 2014:20. doi: 10.1002/pon.3657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasarainen H, Lokman U, Ruutu M, Taari K, Rannikko A. Prostate cancer active surveillance and health-related quality of life: results of the Finnish arm of the prospective trial. BJU Int. 2012;109:1614–1619. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aizer AA, Paly JJ, Efstathiou JA. Multidisciplinary care and management selection in prostate cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2013;23:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van den Bergh RC, de Blok W, van Muilekom E, Tillier C, Venderbos LD, van der Poel HG. Impact on quality of life of radical prostatectomy after initial active surveillance: more to lose? Scand J Urol. 2014;48:367–373. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2013.876097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crook JM, Gomez-Iturriaga A, Wallace K, et al. Comparison of health-related quality of life 5 years after SPIRIT: Surgical Prostatectomy Versus Interstitial Radiation Intervention Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:362–368. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.7305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lane JA, Donovan JL, Davis M, et al. Active monitoring, radical prostatectomy, or radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer: study design and diagnostic and baseline results of the ProtecT randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1109–1118. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daubenmier JJ, Weidner G, Marlin R, et al. Lifestyle and health-related quality of life of men with prostate cancer managed with active surveillance. Urology. 2006;67:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Wang X, Liu T, He Q, Wang Y, Zhang X. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors for treatment of erectile dysfunction following bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.