Abstract

Basements can influence indoor air quality by affecting air exchange rates (AERs) and by the presence of emission sources of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and other pollutants. We characterized VOC levels, AERs and interzonal flows between basements and occupied spaces in 74 residences in Detroit, Michigan. Flows were measured using a steady-state multi-tracer system, and 7-day VOC measurements were collected using passive samplers in both living areas and basements. A walkthrough survey/inspection was conducted in each residence. AERs in residences and basements averaged 0.51 and 1.52 h−1, respectively, and had strong and opposite seasonal trends, e.g., AERs were highest in residences during the summer, and highest in basements during the winter. Air flows from basements to occupied spaces also varied seasonally. VOC concentration distributions were right-skewed, e.g., 90th percentile benzene, toluene, naphthalene and limonene concentrations were 4.0, 19.1, 20.3 and 51.0 μg m−3, respectively; maximum concentrations were 54, 888, 1117 and 134 μg m−3. Identified VOC sources in basements included solvents, household cleaners, air fresheners, smoking, and gasoline-powered equipment. The number and type of potential VOC sources found in basements are significant and problematic, and may warrant advisories regarding the storage and use of potentially strong VOCs sources in basements.

Keywords: Basement, Air exchange rate, VOCs, Transport, Gasoline, Interzonal flows

1. Introduction

Exposure to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) has been associated with irritation, adverse systemic effects and toxicity (Wolkoff et al., 2006, Cometto-Muñiz et al., 2004, Pouli et al., 2003), and indoor air quality (IAQ) studies have indicated the importance of exposures in residences due to the high concentrations and the large amount of time spent at home (Sexton et al., 2004, Sax et al., 2004) This study focuses on residential basements, a building zone which is rarely studied, but which can affect IAQ in several ways. First, basements can contain potentially strong VOC emission sources since solvents, paints, cleaners, oils, and fuels and other VOC-containing products are stored and sometimes used in basements (Dodson et al., 2008, Olson and Corsi, 2001, U.S. EPA, 2012a). VOCs in these products can evaporate and migrate into the living space of the residence (Olson and Corsi, 2001, McGrath and McManus, 1996, Dodson et al., 2007). Second, VOCs in contaminated soils and groundwater can enter basements through cracks and openings in basement floors, walls and drains. Vapor intrusion (VI) of perchloroethylene and petroleum hydrocarbons can be a serious and sometimes widespread problem (McAlary et al., 2011). Third, basements form part of the living space, representing a potentially sizable fraction of the interior volume. Even if the basement is not part of the living area, air in the two zones is coupled to a degree, and the basement volume becomes a portion of the building volume. Finally, basement walls often form part a building's envelope and thus participate in the exchange of indoor and outdoor air, and thus affect the air exchange rate (AER), a critical IAQ parameter. While there are regional differences, basements are very common. For example, 45% of homes in the U.S. have basements, and the percentage reaches 93% in the northeast U.S. (U.S. EPA, 1997).

AERs depend on building characteristics, e.g., tightness and number of floors (Howard-Reed et al., 2002, Dodson et al., 2007), the type of heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) system (Guo et al., 2008, Xu et al., 2010, Wallace et al., 2002), occupant behavior, e.g., window or door opening (Howard-Reed et al., 2002, Wallace et al., 2002), and meteorological conditions, e.g., wind speed and indoor/outdoor temperature differences (Howard-Reed et al., 2002, Johnson et al., 2004, Wallace et al., 2002). AERs and interzonal flows can strongly affect pollutant levels (Holford and Freeman, 1996, Dietz et al., 1986). The importance of air flows from the basement to the living area has been noted in both VI and radon studies (Hernandez and Ring, 1982, U.S. EPA, 2003). However, most studies have assumed that the whole building including the basement is a single and well-mixed zone (Nazaroff et al., 1985, Holford and Freeman, 1996), which likely results in under-predictions of AERs (Ryswyk et al., 2014).

Only a few studies have examined IAQ and airflows in basements. In three houses near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, U.S., AERs in basements ranged from 0.03 to 0.36 h−1, and air flows between these compartments ranged from 4 to 221 m3 h−1, depending whether the active soil depressurization (ASD) system was operating (Turk et al., 2009). In 35 residences in the Boston, Massachusetts area, basements contributed 10 to 20% of the indoor concentrations; concentrations of methylene chloride, ethylbenzene, m,p-xylene and oxylene in basements significantly exceeded levels in (upstairs) living areas; and these differences increased in summer compared to winter (Dodson et al., 2008). In the same study, air flows from basements to occupied zones significantly increased in winter (average of 174 m3 h−1) compared to summer (67 m3 h−1) (Dodson et al., 2007). In two test houses in Paulsboro, NJ, basement ventilation rates ranged from 0.17 to 1.08 h−1, and air flow rates from the basement to the first floor ranged from 29 to 184 m3 h−1 (Olson and Corsi, 2001). Two randomly chosen test houses in the U.K. had quite low flow rates (14 and 63 m3 h−1) from the basement to the living area (McGrath and McManus, 1996). Overall, these studies are limited in terms of the number of residences investigated, the representativeness of results, and the ability to determine variability and seasonal effects.

This paper characterizes VOC levels, emission sources, air flows and pollutant migration between basements and living areas in 74 occupied homes in Detroit, Michigan. A wide range of VOCs was measured, and air flows and AERs were determined using a two-zone two-tracer method. We evaluate effects of house characteristics and AERs on VOC levels, quantify the migration between basements and occupied spaces, evaluate spatial and seasonal variability, and identify emission sources. Multizone model simulations identify important parameters that affected concentrations in the home. Methods are discussed that might be used to reduce occupant exposure.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participant recruitment and schedule

We recruited a total of 126 families living in Detroit, Michigan for a community-based participatory research study investigating the effects of air filters on respiratory health (Du et al., 2011). Households entered the study on a rolling basis from August, 2011 to December, 2012. During this period, 20 families moved once, and eight families moved twice prior to their next visit. In most residences, IAQ monitoring was conducted during an initial ‘baseline’ assessment, and subsequently in two to five ‘seasonal’ assessments spaced two or three months apart. On most weeks, 6 to 10 residences were sampled. Of the residences in the larger study, 74 had basements and VOC measurements were obtained in both the living area and the basement. Depending on the residence, these measurements were made during one to five seasonal assessments. The present study reports on 266 weeklong visits. Recruitment and all other procedures were approved by The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

2.2 IAQ assessment

Using a checklist and direct computer entry, our technician completed a walkthrough inspection to collect information on building characteristics related to IAQ, e.g., the type of heating and cooling system, presence of an attached garage and basement, number of windows, degree of wind sheltering, and the presence of emission sources such as air fresheners, household cleaners, and solvents. Dimensions of rooms, the basement, the overall exterior dimensions of the building, and the number of floors were measured and recorded. Most (75%) but not all homes were made accessible to the technician. From a separate property database, additional information was obtained to help confirm floor and basement areas, year of construction, number of floors, etc. Occupants were queried regarding cigarette smoking in the residence and the numbers of adult and child inhabitants.

VOCs, environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) tracers, and perfluorocarbon tracers (PFTs) for AER determinations were measured using passive samplers over week-long sampling periods in each IAQ assessment. In most residences, two or three passive samplers were placed in two locations in the occupied (upstairs) space, and one sampler was placed in the basement. Target VOCs included nearly 100 compounds (Chin et al., 2014). Total VOC concentrations were estimated as the sum of target VOCs. In addition, four compounds were selected for analysis in the present study (benzene, toluene, naphthalene, limonene), based on the potential to be associated with health outcomes as well as the frequency of occurrence in this study. Benzene and toluene are found in consumer products, e.g., correction (or typing) fluid, glue, cleaning product, shoe polish, air freshener and gasoline, and levels sometimes exceed safe limits (Lim et al., 2014). Limonene is a common constituent of cleaning agents and air fresheners (Nazaroff and Weschler, 2004). Naphthalene can reach high concentrations when used as a pest repellent and deodorant, and it is also emitted from cigarettes and vehicles (Chin et al., 2014, Batterman et al., 2012). Two additional VOCs, 2,5-dimethyl furan (DMF) and 3-ethenyl pyridine (3-EP), were measured as qualitative ETS tracers (Charles et al., 2008). VOCs in ambient air were measured using 24-h active samples collected daily at four Detroit sites (Herman Kiefer Health Center, All Saints Church, Sacred Heart Church, and Our Lady Queen of Peace). Weekly averages were calculated that corresponded to the indoor samples at each residence.

All VOC, ETS and PFT samples were analyzed using thermal desorption, cryofocusing and GC-MS; protocols, sampling and analyses methods have been reported elsewhere (Jia et al., 2006, Batterman et al., 2002). Quality assurance (QA) measures taken to ensure reproducibility and data quality included the use of standard operating protocols, field blanks deployed at each residence and fixed site, quarterly calibrations using authentic standards, internal standards, and duplicate samples. Field blanks had negligible contamination. The precision of PFT and VOCs tracer measurements, based on duplicate samplers, was usually well within 20%. For indoor measurements, detection frequencies for benzene, toluene, naphthalene and limonene (the VOCs emphasized in this paper) were 100%, 100%, 99% and 97%, respectively. 88% of indoor VOC samples passed all QA checks. For outdoor VOC measurements, 64 to 78% (depending on site) of samples passed QA checks. These failure rates were higher than usual, primarily due to rain events, high humidity in basements, and the relatively long sampling period (7-day) or sampling volume, factors that increased the amount of water collected in the passive samplers, which interfered with the laboratory desorption and GS-MS analysis.

2.3 AERs and interzonal flows

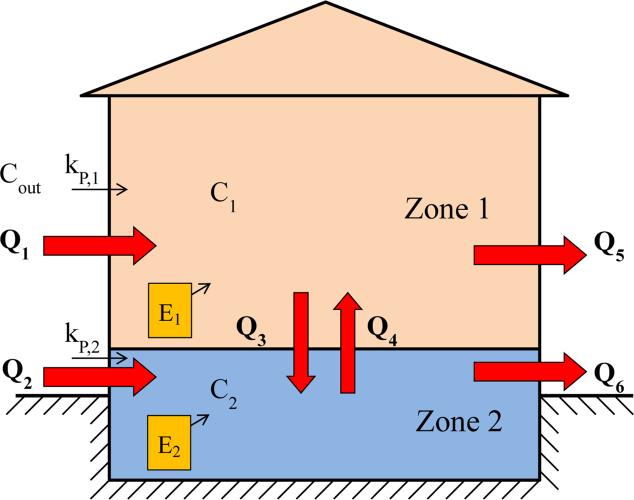

For AER and internal flow determinations, two emitters of hexafluorobenzene (HFB) were placed in the living area of each residence, and one emitter of octafluorotoluene (OFT) was placed in the basement. These passive emitters release the PFT at a constant rate. Each emitter was individually calibrated and checked periodically. Temperature and humidity in each space were continuously monitored to provide corrections, as needed. Artificial mixing in the two zones was not used due to feasibility issues. Referring to Figure 1, air flows Q1 and Q2 for the occupied zone and basement, respectively, and flows between these zones, Q3 and Q4, were determined using the known emission rates and measured concentrations of the two tracers and a well-mixed two zone model (Batterman et al., 2006):

| (1) |

where Q1 and Q2 = volumetric air flow from outdoors into zone 1 and 2, respectively (m3 h−1); Q3 = air flow from zone 1 to 2 (m3 h−1); Q4 = air flow rate from zone 2 to 1 (m3 h−1); CHFB,1 and COFT,1 = concentrations of HFB and OFT measured in zone 1 (mg m−3); CHFB,2 and COFT,2 = concentrations of HFB and OFT measured in zone 2 (mg m−3); and EHFB,1 and EOFT,2 = emission rates of HFB and OFT in zones 1 and 2 (mg h−1), respectively. Eq. (1) assumes that outdoor concentrations are zero, and that the PFTs are inert (removed only by airflows and not by settling, deposition, filtration or reaction). AERi(h−1) in zone i was calculated as Qi/Vi (i=1, 2) where Vi = volume of zone i (m3).

Figure 1.

Configuration of the well mixed two-zone model, and schematic of the two zone IAQ model, showing flows Q1 to Q6 (m3·h−1); concentrations Cout, C1 and C2 (μg·m−3); emission rates E1 and E2 (μg·h−1), and VOCs penetration factors kP,1 and kP,2 (dimensionless).

Interzonal flows, which transport pollutants between zones, were expressed as proportions ranging from 0 to 1:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where αHB = fraction of air coming into the basement arising from the occupied zone; and αHB = fraction of air coming into the occupied zone from the basement. These proportions allow the magnitude of interzonal flows to be compared among buildings of different sizes.

2.4. Two zone IAQ model

A two zone model was set up for each residence. These used two linked mass balance equations to represent the basement (zone 2) and the living area above (zone 1) (Miller and Nazaroff, 2001, Dietz et al., 1986):

| (4) |

| (5) |

where C1 and C2 = concentrations in zones 1 and 2, respectively (μg m−3); t = time (h); Cout = outdoor concentration (μg m−3); kD,1 and kD,2 = pollutant decay rate in zones 1 and 2, respectively (h−1); kP,1 and kP,2= penetration efficiency from outdoor air into zones 1 and 2, respectively (dimensionless); E1 and E2 = emission rates in zones 1 and 2 (mg h−1); Tsa1 and Tsa2 =transfer rate from surface to air in zones 1 and 2 (h−1); CS1 and CS2 = pollutant concentrations on surfaces in zones 1 and 2, respectively (μg m−2); and A1 and A2 = surface area in zones 1 and 2 participating in air-to-surface transfers (m2), respectively. Flows Q and volumes V were defined earlier (Figure 1).

Eqs. (4) and (5) were simplified by assuming steady-state conditions using measured concentrations and flows determined from eq. (1). In addition, for VOCs and short time periods, air-to-surface transfers (Tsa) and decay rates (kD) are small, thus, these terms were set to zero. Finally, VOCs are largely unimpeded on entry to a building, so the penetration efficiency (kP) was set to 1.0. With these assumptions, eqs. (1) and (2) were solved to estimate emission rates E1 and E2:

| (6) |

Eq. (6) highlights that the concentration or mass flux reaching zone 1, for example, results from three contributions: outdoor pollutants that infiltrate (Q1 Cout); emissions in the zone (E1); and the mass flux from zone 2 (Q4 C2). With known or estimated emission rates (E1 and E2) and air flow rates (Q1 through Q6), the contribution of sources in zone i to concentrations in zone j, denoted Ci→j, is:

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

Note that an emission source in one zone affects concentrations in both zones. Also, the allocation accounts for flows that returns the emissions back into the zone.

2.5. Data analysis

House volume was estimated three ways: as the product of the measured footprint area (minus 15% to account for interstitial spaces), the average ceiling height, and the number of floors; as the product of the floor area in the property data base and the estimated ceiling height; and as the sum of room volumes measured in the walkthrough inspection. When two of these three methods agreed within 25%, we took their average. For larger differences, data and calculations were rechecked, and we normally selected volumes calculated using footprint approach, which was viewed as the most reliable method. The basement volume was similarly determined.

We selected only those residences that had valid simultaneous VOC measurements in both the living area and basement, which removed 10 residences. In addition, three cases where the AER estimate was excessively high (≥10 h−1) or very low (≤0.1 h−1) were omitted, which likely resulted from incomplete mixing or other reasons.

Meteorological data were obtained from the Detroit Metropolitan Airport (Weather Underground, Table S1). Potential VOC sources in the study rooms identified in the walk-though inspection were selected for analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Detection frequencies of potential VOCs sources in houses and basements based on the home inspection and walkthrough checklist. In addition, all homes had furnishings and wall coverings that might be VOC sources.

| Potential VOCs sources (N=61) | Detection frequencies (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| House | Basement | |

| Solvents | 13 | 75 |

| Household cleaners | 15 | 70 |

| Air fresheners | 92 | 67 |

| Smoking | 61 | 66 |

| Gas-powered tool | 0 | 31 |

| Glue, adhesives | 25 | 20 |

| Art supplies | 46 | 16 |

| Paint cans | 5 | 15 |

| Motor oil and/or other lubricants | 2 | 10 |

| Gaseline | 0 | 8 |

| Wood finishing supplies | 0 | 8 |

| Nail polish | 18 | 7 |

| Perfume | 11 | 7 |

| Moth crystals | 5 | 7 |

| Mothballs | 7 | 5 |

| Lamp oil | 5 | 5 |

| Paint thinner | 0 | 5 |

| Shoe polish | 5 | 3 |

| Charcoal lighter fluid | 0 | 3 |

| Pesticides, poison baits | 2 | 2 |

| Furniture wax | 0 | 0 |

Differences between concentrations measured simultaneously in basements and living areas were evaluated using paired t-tests, thus accounting for house effects. These and interzonal flow proportion analyses were stratified by season, with summer defined as June, July and August; fall as September, October and November; winter as December, January and February, and spring as March, April and May. Concentration differences between seasons were evaluated using paired t-tests. Differences in medians were evaluated using nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests.

The contribution of emission sources in the basement (and elsewhere) to the concentration in the living space was evaluated using the complete dataset as well as a “censored” dataset, which excluded cases with excessively high or low air flows. We considered the latter more representative and reliable.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Residence characteristics

The final sample included 61 residences with valid measurements. Most (75%) were accessible for the walkthrough survey, 79% were single family houses, and 83% were two stories in height. The number of rooms averaged 7.5 ± 1.2 (± standard deviation; range: 5 - 10), and the occupied area averaged 284 ± 111 m3 (range: 116 - 951 m3). Residences averaged 78 ± 23 (range: 7 - 126) years in age (based on 64% of the sample). Most (87%) used conventional forced air heating systems, and the remainder used steam or hot water radiators. Only 30% of residences had central air conditioning. In most cases, the central heating and air conditioning (if present) system was in the basement. Relatively few (11%) of the residences had an attached garage. Fireplaces with a chimney flue that was vented outdoors were present in 24% of the residences. Most (86%) residences were sheltered by trees, adjacent buildings or other structures that would tend to reduce wind speeds.

The basement volume averaged 154 ± 59 m3 (range: 59 - 457 m3), and the ratio of living zone to basement volumes averaged 1.94 ± 0.70 (median = 1.93). Most basements were partially above grade, and most (93%) had windows. A few residences (4%) had broken or cracked windows, and the windows did not appear to seal tightly in 13% of the basements. Passage doors between basements and living spaces, present in all houses, were not well sealed.

The walkthrough inspection detected many potential VOC sources (Table 1). Air fresheners were found in 92% of the living areas and in 67% of the basements. Household cleaners and solvents, which can contain limonene, benzene, toluene and other aromatics, (Mendell, 2007, Lim et al., 2014) were found in 13 - 15% in the living area, and in 70 - 75% of basements. Gasoline-powered equipment was noted in 31% of basements (0% of living areas); lubricating oils and fuels associated with this equipment contains many volatile components including aliphatic and aromatic VOCs. Evidence of smoking was found in nearly two-thirds of both areas (61 - 66%), and about one-third of occupants reported regular burning of candles (39% of residences, average use of 5.3 ± 5.8 h/week) or incense (33% of residences, 5.1 ± 8.5 h/week). Such activities produce a range of VOCs (Charles et al., 2008, Manoukian et al., 2013). About 20% of the residences had gas stoves or ovens that were used at least twice per week. These and the other potential sources listed in Table 1 can elevate VOC concentrations. Particularly notable is the presence of solvents and gasoline-powered equipment in basements since these items can be strong VOC sources.

3.2. AERs in residences and basement

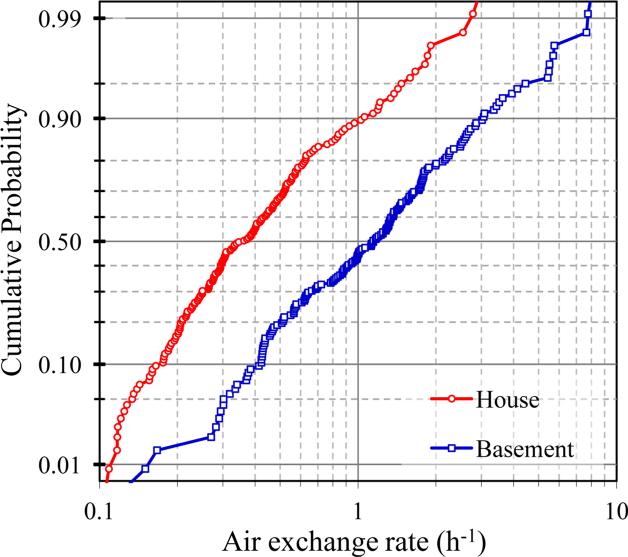

In residences, AERs averaged 0.51 ± 0.48 h−1 (median = 0.35 h−1, n= 170; interquartile range: IQR = 0.23 - 0.56 h−1). AERs were much higher in basements, averaging 1.52 ± 1.42 h−1 (median = 1.15 h−1, n=170; IQR = 0.58 - 1.79 h−1). The AERs consider only outside air entering the zone (flows between zones is ignored). The distribution of AERs in both houses and basements were lognormal, as shown on log-probability plots (Figure 2; p=0.42, p=0.55, Shapiro-Wilk tests). Living zone AERs were significantly and positively correlated with indoor, basement and outdoor temperatures (Spearman r=0.34, 0.22, and 0.31, respectively), and negatively correlated with (total) VOC levels in residence, house volume and wind speed (r=-0.32, -0.25, -0.22). In contrast, basement AERs were negatively correlated with indoor, basement and outdoor temperatures (r=-0.18, -0.18, -0.28). Basement AERs were also negatively correlated with total VOC levels in the living zone and basement (r = -0.33, -0.41), and positively correlated with residence age (r=0.34).

Figure 2.

Log probability plot of air exchange rates in houses and basements (visit-based). N=170 for both houses and basements.

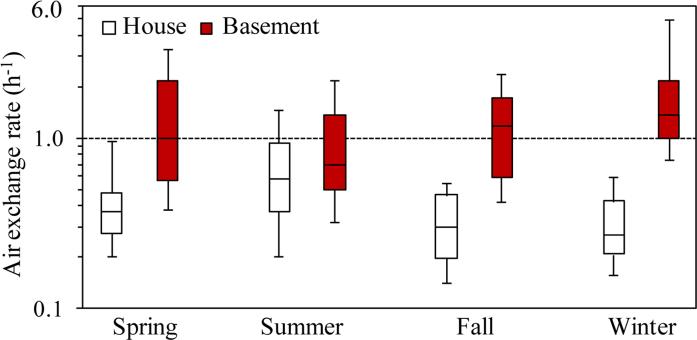

AERs in both the living zone and basement differed by season (p<0.01, Kruskal-Wallis tests; Figure 3; air flows are shown in Table 2). In summer, living zone AERs were highest and basement AERs were lowest, and the median basement/living zone AER ratio was 1.3. In winter, the opposite trend occurred: living zone AERs were at their minimum and basement AERs were at their highest; and the median basement/living zone AER ratio jumped to 4.4. These are large changes.

Figure 3.

Air exchange rates in houses and basements. Boxplots show 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 90th percentiles by seasons.

Table 2.

Air flow rates (m3 h−1) from outdoor into house (Q1) and basement (Q2), and interzonal air flow rates from house to basement (Q3) and from basement to house (Q4), all by season.

| Season | Statistics | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | N | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 |

| Mean | 130 | 237 | 125 | 107 | |

| SD | 95 | 242 | 211 | 158 | |

| Median | 117 | 185 | 46 | 47 | |

| 90th | 185 | 458 | 262 | 184 | |

| Summer | N | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 |

| Mean | 187 | 164 | 95 | 37 | |

| SD | 129 | 157 | 86 | 34 | |

| Median | 155 | 103 | 69 | 30 | |

| 90th | 362 | 368 | 222 | 66 | |

| Fall | N | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Mean | 117 | 204 | 105 | 94 | |

| SD | 158 | 151 | 126 | 79 | |

| Median | 80 | 170 | 65 | 69 | |

| 90th | 173 | 406 | 202 | 201 | |

| Winter | N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Mean | 97 | 326 | 145 | 141 | |

| SD | 96 | 406 | 101 | 110 | |

| Median | 83 | 191 | 124 | 117 | |

| 90th | 123 | 656 | 281 | 222 | |

| All | N | 170 | 170 | 170 | 170 |

| Mean | 134 | 227 | 116 | 92 | |

| SD | 129 | 251 | 139 | 109 | |

| Median | 97 | 156 | 71 | 57 | |

| 90th | 249 | 423 | 243 | 198 | |

| p-value* | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.010 | <0.001 | |

p-value from Kruskal-Wallis test

Air exchange in residential buildings results from wind- and pressure-driven infiltration/exfiltration through cracks and openings in the building envelope (including the ‘stack’ effect induced by temperature gradients), ‘natural’ ventilation through open windows and doors, mechanical ventilation using window and attic fans and window air conditioners, and infiltration due to the need for ‘make-up’ air exhausted by furnaces, hot water heaters, fireplaces, and bathroom and kitchen exhaust fans. In living areas, higher AERs in summer can occur due to window opening and fan use, especially during when temperatures are mild or moderate (Wallace et al., 2002, Yamamoto et al., 2010). Window air conditioner use may also increase AERs. Both factors likely increased summer AERs in Detroit homes, especially since few homes have central air conditioning.

We found considerable seasonal variation of AERs, particularly in basements. Such variation depends on region and climate, among other factors (Wallace et al., 2002, Yamamoto et al., 2010). Generally, higher AERs are expected as indoor/outdoor temperature differences and wind speeds increase; such effects can be enhanced in older residences and residences in poor condition.

AERs in basements were consistently higher than AERs in living zones. The high AERs in basements and their temporal patterns can be explained by several factors. First, as noted earlier, a number of basements had poorly sealing windows. Second, since these windows are rarely, if ever, opened, AERs in basements may respond more consistently to the driving forces of wind and stack effects, which would tend to increase AERs in winter when indoor-outdoor temperature differences and wind speeds are greater (Table S1). Third, most residences had natural gas furnaces and hot water heaters located in the basement; most of these systems use basement air for combustion. The leaky basement envelope and the (increased) need for make-up air during the winter heating season will increase exchange. Finally, in summer, basements are typically cooler than outdoors and upstairs occupied portions. Since minimal if any exchange can take place in the portion of the building envelope below grade in the basement, the stable stratification of air will tend to decrease basement AERs in the summer.

Factors affecting AERs in residences include building size and height, condition, construction, degree of wind sheltering, and climate (Du et al., 2012). In a previous Detroit study that used a larger sample (including 61 of the residences in the present study), AERs were slightly higher, averaging 0.73 ± 0.76 h−1 (n=126). This difference may be due to several factors, e.g., the residences in the larger study were slightly newer (58 versus 78 years), bigger (367 versus 284 m3), and more homes were studied in spring and summer (Du et al., 2012). Some selection bias may be present in that we considered only residences with accessible basements, while the larger study included several apartments and multifamily homes. The AERs in this study are comparable to those reported in other recent studies using the constant injection tracer gas method, e.g., AERs were slightly lower than those measured in more moderate climates (0.87 h−1 for Elizabeth, NJ, 0.88 h−1 for Houston, TX) (Yamamoto et al., 2010), higher than those in newer residences in nearby Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti, MI (0.43 ± 0.37 h−1, n=15) (Batterman et al., 2007) and in Windsor, Ontario, Canada (0.32 h−1 for winter; 0.19 h−1for summer) (Stocco et al., 2008), and also higher than those modeled in a 19 city study of single-family houses (0.43 h−1, n=140) (Persily et al., 2010).

Few studies have reported on AERs in basements. In Paulsboro, NJ, AERs in two basements ranged from 0.17 to 1.08 h−1, depending on the pressure difference (Olson and Corsi, 2001). In the U.K., AERs in basements of two random chosen houses were 1.8 and 4.9 h−1; controlling factors were suggested to be cracks between floor-boards and between floors and walls, visible openings between the zones, and the presence of a ceiling membrane (McGrath and McManus, 1996). In Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, basement AERs in three houses were very low, ranging from 0.03 to 0.20 h−1 (active soil depressurization or ASD off) and 0.04 to 0.36 h−1 (ASD on). ASD operation generally increased basement AERs, especially during the summer and parts of the spring and fall (Turk et al., 2009).

3.3. Air flows

Air flows from outdoors and into the living zone and basement differed by season and showed similar seasonal patterns (Table 2). The interzonal air flows (in both directions) were highest in winter and lowest in summer, e.g., basement to living zone flows averaged 141 ± 110 m3 h−1 in winter and only 37 ± 34 m3 h−1 in summer. The portion of air entering the living zone from the basement (αHB) also varied seasonally, with 58 ± 14% (highest) in winter dropping to 21 ± 18% in summer (lowest, Table 3), likely reflecting increased natural ventilation during the summer and enhanced stack effect in the winter. Outside air flows into the living zone and basement were correlated with residence age (r=0.25, p=0.005 for Q1; r=0.44, p<0.001 for Q2). Of the study residences, 14 older residences (90 ± 11 years old) consistently had high air flows into the basement from outdoors (Q2 = 382 ± 229 m3 h−1) across the seasons compared to the remainder of homes (68± 28 years, Q2 = 174 ± 237 m3 h−1). Living zone AERs were negatively correlated with αHB (r =-0.58, p <0.001), as were basement AERs with αHB (r = -0.45, p <0.001), indicating that these older residences obtained most air through the envelope, and not from the basement.

Table 3.

Proportion of air flow in the basement that arises from the house (αHB), and proportion of air flow in the house that arises from basement (αBH), all by season.

| Proportion | Season | N | Mean | SD | Median | 90th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α HB | Spring | 41 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.57 |

| Summer | 44 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.39 | 0.61 | |

| Fall | 50 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.61 | |

| Winter | 35 | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.38 | 0.64 | |

| All | 170 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.62 | |

| p-value* | 0.090 | |||||

| α BH | Spring | 41 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.71 |

| Summer | 44 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.41 | |

| Fall | 50 | 0.46 | 0.17 | 0.48 | 0.65 | |

| Winter | 35 | 0.58 | 0.14 | 0.59 | 0.76 | |

| All | 170 | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.40 | 0.69 | |

| p-value* | <0.001 |

p-value from Kruskal-Wallis test

The Boston study also reported the highest air flows between basements and occupied zones in winter (174 ± 164 m3 h−1) and the lowest in summer (67 ± 54 m3 h−1), as well as the highest proportion of air flow from basement into residence area (47 ± 26% in winter, 26 ± 34 % in summer) (Dodson et al., 2007). This study was based on only 35 homes, and the large variability was attributed to building age (before 1950/1960). It also studied larger homes (158 - 242 m2) compared to the present study. In the three Pennsylvania houses, air flow from upstairs to the basement ranged from 4 to 71 m3 h−1 (ASD off) and 5 to 221 m3 h−1 (ASD on), and portion of air entering into basement from upstairs averaged 44 ± 23% and 59 ± 21%, respectively (Turk et al., 2009). These houses, which had occupant complaints related to dampness, had mostly unoccupied and unfinished basements with concrete slab floors and central forced air heating and cooling equipment. In the two Paulsboro, NJ houses, basement to first floor flows ranged from 29 to 184 m3 h−1 (assuming basement air goes only to the first floor and that the basement was well-mixed) (Olson and Corsi, 2001). In the two test houses in the UK, basement to first floor flows were 14.1 and 62.8 m3 h−1. In the first floor, air exited the ceiling and did not return (McGrath and McManus, 1996). These two houses are not representative of Detroit residences due to this decoupling, as well as to age and condition differences.

3.4. VOC concentrations

VOC concentrations in the living zones, basements and outdoors are summarized in Table 4. In living areas, median levels of benzene, toluene, naphthalene and limonene were 1.4, 6.3, 0.9 and 13.7 μg m−3, similar to median levels in basements (1.5, 5.9, 1.1 and 9.0 μg m−3). Outdoor concentrations were much lower, e.g., median levels of each VOC fell below 1 μg m−3. Concentration distributions were right-skewed, especially for toluene and naphthalene, which reached levels approaching or exceeding 1000 μg m−3. The single highest indoor naphthalene measurement was 1117 μg m−3 (measured in spring); the average level in this house, based on four visits in different seasons, was also very high (616 μg m−3). These excessive concentrations likely result from the inappropriate use of repellents and deodorants (Batterman et al., 2012). Considering residences with the highest concentrations, e.g., the 90th, 95th percentile and maximum concentrations in Table 4, benzene and toluene levels were highest in basements, probably due to the storage and possible use of solvents, gasoline, and gasoline-powered equipment in this location, while naphthalene and limonene were highest in living areas, also consistent with expected locations of use of cleaners and deodorizers containing these VOCs.

Table 4.

Concentrations of benzene, toluene, naphthalene, and limonene detected in the house, basement and outdoor. Uses visit-based statistics.

| μg m−3 | Benzene |

Toluene |

Naphthalene |

Limonene |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | House | Basement | Outdoor | House | Basement | Outdoor | House | Basement | Outdoor | House | Basement | Outdoor |

| N | 170 | 170 | 166 | 170 | 170 | 166 | 170 | 170 | 166 | 170 | 170 | 166 |

| Mean | 2.21 | 2.98 | 0.87 | 11.81 | 21.75 | 1.96 | 26.30 | 17.19 | 0.16 | 20.16 | 16.60 | 0.27 |

| SD | 2.72 | 5.88 | 0.19 | 33.62 | 77.30 | 0.66 | 118.09 | 65.78 | 0.06 | 21.87 | 21.95 | 0.19 |

| Median | 1.36 | 1.51 | 0.87 | 6.26 | 5.92 | 1.86 | 0.93 | 1.09 | 0.15 | 13.65 | 9.02 | 0.22 |

| 90th | 4.03 | 4.24 | 1.09 | 19.07 | 28.00 | 2.83 | 20.33 | 11.11 | 0.24 | 51.03 | 48.08 | 0.39 |

| 95th | 5.83 | 8.82 | 1.19 | 25.23 | 58.53 | 3.06 | 101.50 | 115.50 | 0.26 | 66.14 | 62.59 | 0.59 |

| Max | 20.97 | 54.02 | 1.41 | 422.14 | 888.72 | 5.44 | 1117.23 | 503.54 | 0.41 | 134.85 | 114.86 | 1.30 |

Concentrations in the living area and basement were highly correlated (Spearman r = 0.72, 0.80, 0.81, and 0.76 for benzene, toluene, naphthalene and limonene, Table S3), reflecting the interzonal air flows. Among pollutants, indoor concentrations of benzene and toluene were highly correlated (r = 0.44 to 0.80), as was naphthalene with benzene and toluene (r = 0.47 to 0.81), suggesting common sources or common factors affecting these pollutants. Indoor and outdoor concentrations had minimal correlation, again showing the dominance of the indoor sources.

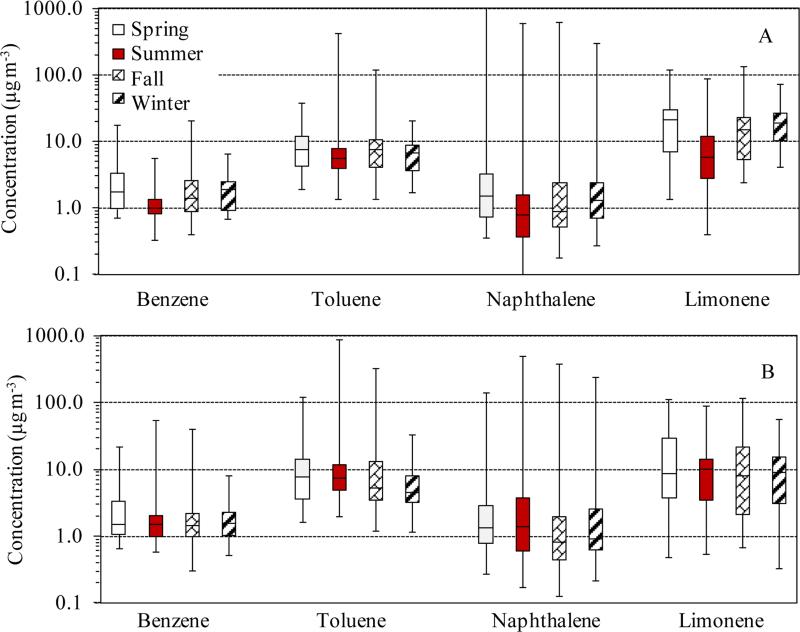

Averaging across seasons, 65% of residences had benzene concentration exceeding 1 μg m−3, , which corresponds to a lifetime leukemia risk of 6×10–6 (U.S. EPA, 2012b) and 24% of residences had naphthalene levels exceeding 3 μg m−3, the chronic inhalation reference concentration (RfC) (MDEQ, 2012). Benzene and limonene levels in residences varied seasonally (p=0.004, p<0.001, Kruskal-Wallis tests) with the lowest levels in summer and the highest in winter or spring (Figure 4). Toluene and naphthalene showed similar trends, although changes were smaller and not statistically significant.

Figure 4.

Concentrations of benzene, toluene, naphthalene, and limonene in houses (A) and basements (B). Boxplots show minimum, maximum, 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles.

Median VOC levels resembled those in the parent study (1.5, 6.0, 1.0 and 16.2 μg m−3 for benzene, toluene, naphthalene and limonene, respectively) (Chin et al., 2014, Batterman et al., 2012). Because the number of visits to each residence was uneven (Table S2), we checked differences between statistics based on residence averages (n=61) and visits (n= 170). Residence- and visit-based median differences were within 15% for four VOCs, suggesting seasonal or sampling (selection) biases are minimal for these VOC levels. Also, previously we showed that benzene, toluene and limonene concentrations in Detroit residences (medians, ranges, etc.) are comparable to those in reported in several other US studies (Logue et al., 2011), though variability at the residence level can be significant. This also applies to naphthalene, although the present study has raised the highest level (556 μg m−3) that has been reported previously for this chemical (Batterman et al., 2012).

Residences contain many VOC emission sources, e.g., benzene and toluene are components of solvents, gasoline, paints, glue/adhesives, cigarette smoke, candle and incense burning (Lim et al., 2014, Manoukian et al., 2013), limonene is in cleaning products, air fresheners, and fragrances (Nazaroff and Weschler, 2004), and naphthalene (or paradichlorobenzene) is the sole ingredient of many “moth balls,” other repellents and deodorants (Batterman et al., 2012). Other than a surprisingly high frequency (33-39%) of candle and incense burning reported in our survey, we did not identify any new VOC sources. However, this study is striking in showing a very high prevalence (75%) of potential sources in basements, and the significance of these sources is supported by basement/indoor concentration ratios that frequently exceeded one. The storage of gasoline-powered equipment in basements is also troubling, since especially older equipment may leak and release fuel and vapors, e.g., benzene. Emission rates from these sources and the resulting concentrations will depend on the source itself, as well as temperature, season, local ventilation, sampling location, averaging time, and meteorology (Johnson et al., 2004, Wallace et al., 2002).

As noted earlier, very few studies have reported VOC levels in basements. Compared to this study, the Boston study reported similar levels of benzene (median = 1.6 μg m−3), higher levels of toluene (14 μg m−3), and lower levels of limonene (3.3 μg m−3) (Dodson et al., 2007). VOC levels in basements have been reported in several VI studies, e.g., a California house located 70 m from a landfill had unremarkable level of 26 VOCs (Hodgson et al., 1992). The lack of studies reporting measurements limits comparisons.

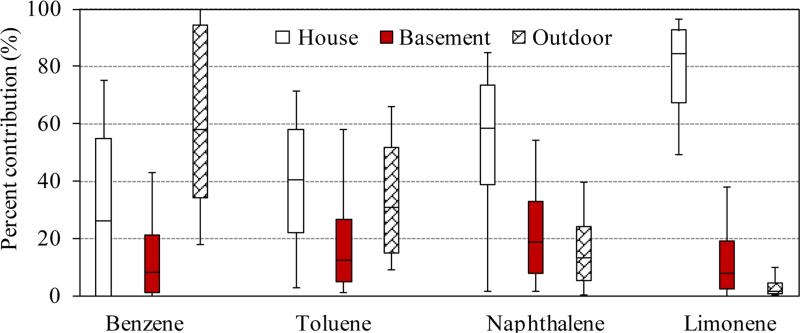

3.5 Apportionment of VOC sources

Contributions to VOC concentrations measured in the living areas were apportioned to sources in the living area itself, the basement, and outdoor sources (Figure 5). Apportionments varied widely across homes, and total contributions summed only approximately to 100%. Considering the median apportionments, three patterns are suggested: naphthalene and limonene originated mostly from sources in the living space (e.g., deodorizers, cleaners, furniture polish); benzene originated from outdoor sources, e.g., vehicle-related emissions; and both home and outdoor sources contributed toluene. Contributions from the basement ranged from 8% (benzene) to 19% (naphthalene). However, in some residences, basements accounted for 40 to 60% of indoor concentrations. Outdoor contributions varied by season, with higher ratios in summer than winter. Many of these results are comparable to those reported in the Boston study (Dodson et al., 2007).

Figure 5.

Apportions (as percent contribution) from houses, basements, and outdoor “zones” to indoor concentrations for four VOCs (benzene, toluene, naphthalene and limonene). Boxplots show 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 90th percentiles.

An important factor limiting the influence of basements is the higher AER in this space, which would dilute VOCs before migrating to the occupie d space. In this study, it should be noted that we could not apportion sources in an attached garage (these could be assigned to either outdoor air, indoor or basement sources), but few of the study homes had attached garages.

3.6 Recommendations regarding basement sources

We view the number and type of potential VOC sources found in basements as significant and problematic. In Detroit, the relatively high AERs in basements were advantageous in diluting VOCs. However, many new residences have very low AERs, and AERs in basements may be particularly low, especially in summer. In older residences, energy conservation measures will also tighten-up basements and reduce AERs, thus increasing VOC levels. Advisories against the storage and use of potentially strong VOC emitting sources (e.g., gasoline and gasoline-powered equipment) in basements appear warranted. Emissions could be reduced if basements or storage areas had exhaust ventilation, or if storage cabinets with exhaust or vapor traps (e.g., using activated carbon) were used, but these options are likely to be expensive and infeasible in many cases. Possibly many or most building occupants do not good indoor storage alternatives, thus the provision -- and use -- of outdoor storage sheds or detached garages for storing and using VOC-emitting materials could represent a viable option to reduce exposures.

We previously noted the importance of VOC sources in at tached garages to residential air quality (Batterman et al., 2007). Storage of solvents, fuels and vehicles in garages presents similar issues as basements. However, new ventilation codes recognize the importance of minimizing air migration from garages to living spaces, and require measures to depressurize the garage or minimize air flow between these zones. Such measures do not exist for basements and may not be practical. Further, basements may form part of the living space, and as demonstrated in this study, there is considerable coupling between basements and living spaces. Thus, elimination of sources in basements is the most appropriate remedy.

3.7 Study limitations

This study has several limitations. Potential sources in residences and basements were determined by visual inspection, and some sources may not have been identified. We obtained only limited information regarding occupant activities that might affect AERs, interzonal flows, and VOC levels, e.g., the opening and positioning of windows and doors, area of openings (e.g., cracks) between the living area and basement, and between the floor and wall. We did not account for attached garages, which were present in 11% of the study homes. (A three-tracer gas method could be used to distinguish flows between the living area, basements and garages.) As noted, attached garages can be important VOC sources (Batterman et al., 2007). Attached garages were not accounted for in the apportionment of VOC sources, although the air exchange and interzonal measurements do account for a garage, if present, e.g., flows from outside air, to the garage, to the basement, and to the living area would be identified as flows from outside air, to the basement, to the living area. The Detroit residences were mostly low-income family homes, and most were smaller and older than the U.S. averages. Results may not apply to homes with different characteristics. The measurements and models assumed steady-state and well-mixed conditions, and short-term effects (e.g., hourly) were not considered. Spaces in residences may not be fully mixed; leading to errors in AER and apportionment estimates; however, the use of week-long measurements may diminish the magnitude of this problem. VOC levels immediately outside residences were not monitored; rather, average outdoor concentrations at several Detroit area sites were used. The use of estimated building volumes may introduce some error. Finally, we did not account for vapor intrusion into the basement, a problem in portions of Detroit, although only small impacts are expected in this study.

4. Conclusions

We investigated AERs, interzonal flows, and concentrations of benzene, toluene, naphthalene, and limonene in 74 homes in Detroit, Michigan. AERs averaged 0.51 ± 0.48 h−1 in living areas, and much higher, 1.52 ± 1.42 h−1, in basements. AERs in living areas increased in summer and fell in winter; the opposite trend with much larger swings occurred for AERs in basements.

In winter, interzonal flows and the proportion of air entering the living area from the basement were large, suggesting little isolation between basement and living areas and the significance of the stack effect. Median levels of the four VOCs were comparable to recent studies, but distributions were highly skewed, several extremely high VOC concentrations were measured, and concentrations in basements sometimes exceeded levels in living areas. The study results, specifically, the basement AERs and interzonal flow rates, can be used to improve characterizations of IAQ, particularly for vapor intrusion applications.

As expected, living areas of most residences contained many potential VOC sources. However, most basements also contained potential sources, including solvents, household cleaners, air fresheners, smoking, and gasoline-powered equipment. The number and type of potential VOC sources found in basements are significant and problematic, and warrant advisories against the storage and use of potentially strong VOC emitting items in basements, such as gasoline containers and gasoline-powered equipment.

Supplementary Material

Practical implications.

Few IAQ studies have examined basements. A sizable volume of air can flow between the basement and living area, and AERs in these two zones can differ considerably. In many residences, the basement contains significant emission sources and contributes a large fraction of VOC concentrations found in the living area. Exposures can be lowered by removing VOC sources from the basement; other exposure management options, such as local ventilation or isolation, are unlikely to be practical.

Acknowledgements

We thank our Detroit participants, our Detroit and Ann Arbor staff including Sonya Grant, Leonard Brakefield, Dennis Fair, Ricardo de Majo, Andrew Ekstrom, and our CAAA Steering Committee members (Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (ACCESS); Community Health & Social Services Center (CHASS); Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation (DHDC); Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice (DWEJ); Friends of Parkside (FOP); Latino Family Services (LFS); Southwest Detroit Environmental Vision; Institute for Population Health; Warren/Conner Development Coalition; City of Detroit Dept of Health and Wellness Promotion, and the University of Michigan Schools of Public Health and Medicine. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. This study was conducted as part of National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIEHS) grant R01-ES014566-01A1/S1, “A Community Based Participatory Research Intervention for Childhood Asthma Using Air Filters and Air Conditioners.” Additional support was provided by grant NIEHS P30ES017885 entitled “Lifestage Exposure and Adult Disease.”

References

- Batterman S, Chin JY, Jia C, Godwin C, Parker E, Robins T, Max P, Lewis T. Sources, concentrations, and risks of naphthalene in indoor and outdoor air. Indoor Air. 2012;22:266–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2011.00760.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterman S, Jia CR, Hatzivasilis G. Migration of volatile organic compounds from attached garages to residences: A major exposure source. Environ Res. 2007;104:224–240. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterman S, Jia CR, Hatzivasilis G, Godwin C. Simultaneous measurement of ventilation using tracer gas techniques and VOC concentrations in homes, garages and vehicles. J Environ Monitor. 2006;8:249–256. doi: 10.1039/b514899e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterman S, Metts T, Kalliokoski P. Diffusive uptake in passive and active adsorbent sampling using thermal desorption tubes. J Environ Monitor. 2002;4:870–878. doi: 10.1039/b204835c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles SM, Jia C, Batterman SA, Godwin C. VOC and particulate emissions from commercial cigarettes: Analysis of 2,5-DMF as an ETS tracer. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:1324–1331. doi: 10.1021/es072062w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin JY, Godwin C, Parker E, Robins T, Lewis T, Harbin P, Batterman S. Levels and sources of volatile organic compounds in homes of children with asthma. Indoor Air. 2014;24:403–415. doi: 10.1111/ina.12086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cometto-Muñiz JE, Cain WS, Abraham MH. Detection of single and mixed VOCs by smell and by sensory irritation. Indoor Air. 2004;14:108–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz RN, Goodrich RW, Cote EA, Wieser RF. Detailed description and performance of a passive perfluorocarbon tracer system for building ventilation and air exchange measurements, Measured air leakage of buildings. ASTM STP. 1986;904:203–264. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson RE, Levy JI, Shine JP, Spengler JD, Bennett DH. Multi-zonal air flow rates in residences in Boston, Massachusetts. Atmos. Environ. 2007;41:3722–3727. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson RE, Levy JI, Spengler JD, Shine JP, Bennett DH. Influence of basements, garages, and common hallways on indoor residential volatile organic compound concentrations. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:1569–1581. [Google Scholar]

- Du L, Batterman S, Godwin C, Chin J-Y, Parker E, Breen M, Brakefield W, Robins T, Lewis T. Air Change Rates and Interzonal Flows in Residences, and the Need for Multi-Zone Models for Exposure and Health Analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2012;9:4639–4661. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9124639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L, Batterman S, Parker EA, Godwin C, Chin J-Y, O'toole A, Robins TG, Brakefield-Caldwell W, Lewis T. Particle Concentrations and Effectiveness of Free-Standing Air Filters in Bedrooms of Children with Asthma in Detroit, Michigan. Build Environ. 2011;46:2303–2313. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Morawska L, He C, Gilbert D. Impact of ventilation scenario on air exchange rates and on indoor particle number concentrations in an air-conditioned classroom. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:757–768. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez TL, Ring JW. Indoor radon source fluxes: Experimental tests of a two-chamber model. Environ Int. 1982;8:45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson AT, Garbesi K, Sextro RG, Daisey JM. Soil-gas contamination and entry of volatile organic compounds into a house near a landfill. J Air Waste Manage. 1992;42:277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Holford DJ, Freeman HD. Effectiveness of a passive subslab ventilation system in reducing radon concentrations in a home. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:2914–2920. [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Reed C, Wallace LA, Ott WR. The effect of opening windows on air change rates in two homes. J Air Waste Manage. 2002;52:147–159. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2002.10470775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C, Batterman S, Chernyak S. Development and comparison of methods using MS scan and selective ion monitoring modes for a wide range of airborne VOCs. J Environ Monitor. 2006;8:1029–1042. doi: 10.1039/b607042f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T, Myers J, Kelly T, Wisbith A, Ollison W. A pilot study using scripted ventilation conditions to identify key factors affecting indoor pollutant concentration and air exchange rate in a residence. J Expo Anal Env Epid. 2004;14:1–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SK, Shin HS, Yoon KS, Kwack SJ, Um YM, Hyeon JH, Kwak HM, Kim JY, Kim TY, Kim YJ. Risk Assessment of Volatile Organic Compounds Benzene, Toluene, Ethylbenzene, and Xylene (BTEX) in Consumer Products. J Toxicol Env Health, Part A. 2014;77:1502–1521. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2014.955905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logue J, Mckone T, Sherman M, Singer B. Hazard assessment of chemical air contaminants measured in residences. Indoor Air. 2011;21:92–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2010.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoukian A, Quivet E, Temime-Roussel B, Nicolas M, Maupetit F, Wortham H. Emission characteristics of air pollutants from incense and candle burning in indoor atmospheres. Environ Sci Pollut R. 2013;20:4659–4670. doi: 10.1007/s11356-012-1394-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcalary TA, Provoost J, Dawson HE. Dealing with Contaminated Sites. Springer; 2011. Vapor intrusion; pp. 409–453. [Google Scholar]

- Mcgrath P, Mcmanus J. Air infiltration from basements and sub-floors to the living space. Building Services Engineering Research and Technology. 1996;17:85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mendell MJ. Indoor residential chemical emissions as risk factors for respiratory and allergic effects in children: a review. Indoor Air. 2007;17:259–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2007.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MDEQ Michigan Air Toxic Program Screening Level List. 2012 http://www.deq.state.mi.us/itslirsl/results.asp?Chemical_Name=&CASNumber=&cm dShowAll=Show%20All%20Chemicals&cmdSubmit=&OrderBy=AQD_Secondary_ITSL&page=1.

- Miller SL, Nazaroff WW. Environmental tobacco smoke particles in multizone indoor environments. Atmos. Environ. 2001;35:2053–2067. [Google Scholar]

- Nazaroff WW, Feustel H, Nero AV, Revzan KL, Grimsrud DT, Essling MA, Toohey RE. Radon transport into a detached one-story house with a basement. Atmos. Environ. 1985;19:31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Nazaroff WW, Weschler CJ. Cleaning products and air fresheners: exposure to primary and secondary air pollutants. Atmos. Environ. 2004;38:2841–2865. [Google Scholar]

- Olson DA, Corsi RL. Characterizing exposure to chemicals from soil vapor intrusion using a two-compartment model. Atmos. Environ. 2001;35:4201–4209. [Google Scholar]

- Persily A, Musser A, Emmerich SJ. Modeled infiltration rate distributions for U.S. housing. Indoor Air. 2010;20:473–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2010.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouli AE, Hatzinikolaou DG, Piperi C, Stavridou A, Psallidopoulos MC, Stavrides JC. The cytotoxic effect of volatile organic compounds of the gas phase of cigarette smoke on lung epithelial cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2003;34:345–355. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryswyk KV, Wallace L, Fugler D, Macneill M, Héroux M-È, Gibson MD, Guernsey JR, Kindzierski W, Wheeler AJ. Estimation of bias with the single zone assumption in measurement of residential air exchange using the perfluorocarbon tracer gas method. Indoor Air. 2014 doi: 10.1111/ina.12171. DOI: 10.1111/ina.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sax SN, Bennett DH, Chillrud SN, Kinney PL, Spengler JD. Differences in source emission rates of volatile organic compounds in inner-city residences of New York City and Los Angeles. J Expo Anal Env Epid. 2004;14:S95–S109. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton K, Adgate JL, Ramachandran G, Pratt GC, Mongin SJ, Stock TH, Morandi MT. Comparison of personal, indoor, and outdoor exposures to hazardous air pollutants in three urban communities. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:423–430. doi: 10.1021/es030319u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocco C, Macneill M, Wang D, Xu X, Guay M, Brook J, Wheeler AJ. Predicting personal exposure of Windsor, Ontario residents to volatile organic compounds using indoor measurements and survey data. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:5905–5912. [Google Scholar]

- Turk B, Hughes J, Center SRRT. Movement and Sources of Basement Ventilation Air and Moisture During ASD Radon Control. 2009 http://www.epa.gov/radon/pdfs/moisturestudy_analysis.pdf.

- U.S. EPA Exposure Factors Handbook (1997 Final Report) 1997 http://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/cfm/recordisplay.cfm?deid=12464.

- EPA US. User's guide for evaluating subsurface vapor intrusion into buildings. 2003 http://www.epa.gov/oswer/riskassessment/airmodel/pdf/2004_0222_3phase_users_guide.pdf.

- U.S. EPA Indoor ambient air monitoring, vapor intrusion sampling, and assessment activities report. 2012a http://www.epa.gov/reg3hwmd/npl/PASFN0305521/reports/RI%20Addendum/Part_3-VI_Report-PII_Figs_etc_deleted.pdf.

- U.S. EPA Integrated Risk Information System Database for Risk Assessment. 2012b http://www.epa.gov/iris/

- Wallace L, Emmerich SJ, Howard-Reed C. Continuous measurements of air change rates in an occupied house for 1 year: the effect of temperature, wind, fans, and windows. J Expo Anal Env Epid. 2002;12:296–306. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkoff P, Wilkins C, Clausen P, Nielsen G. Organic compounds in office environments–sensory irritation, odor, measurements and the role of reactive chemistry. Indoor air. 2006;16:7–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2005.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Raja S, Ferro AR, Jaques PA, Hopke PK, Gressani C, Wetzel LE. Effectiveness of heating, ventilation and air conditioning system with HEPA filter unit on indoor air quality and asthmatic children's health. Build Environ. 2010;45:330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N, Shendell DG, Winer AM, Zhang J. Residential air exchange rates in three major US metropolitan areas: results from the Relationship Among Indoor, Outdoor, and Personal Air Study 1999–2001. Indoor Air. 2010;20:85–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2009.00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.