Abstract

Nearly one-third of South African men report enacting intimate partner violence (IPV). Beyond direct health consequences for women, IPV is also linked to varied risk behaviours among men who enact it, including alcohol abuse, risky sex, and poor health care uptake. Little is known about how to reduce IPV perpetration among men. We conducted retrospective, in-depth interviews with men (n=53) who participated in a rural South African program that targeted masculinities, HIV risk, and IPV. We conducted computer-assisted thematic qualitative coding alongside a simple rubric to understand how the program may lead to changes in IPV perpetration. Many men described new patterns of reduced alcohol intake and improved partner communication, allowing them to respond in ways that did not lead to the escalation of violence. Sexual decision-making changed via reduced sexual entitlement and increased mutuality about whether to have sex. Men articulated the intertwined nature of each of these topics, suggesting a syndemic lens may be useful for understanding IPV. These data suggest that alcohol and sexual relationship skills may be useful levers for future IPV programming, and that IPV may be a tractable issue as men learn new skills for enacting masculinities in their household and in intimate relationships.

Keywords: men, masculinity, South Africa, sexual violence, relationships

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a leading cause of morbidity, particularly among women of reproductive age. Recent research suggests that 30% of women globally experience physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner (WHO 2013; Devries et al. 2013). Large studies among South African men found that 27.5 – 31.8% report enacting violence towards partners (Dunkle et al. 2006), and 27.6% of men have ever raped (Jewkes et al. 2011), rates that are consistent with population-based findings from recent multi-country studies in other regions (Barker et al. 2011; Fulu et al. 2013).

Experiencing IPV leads to direct health consequences for women, including physical trauma and pain, declines in reproductive and mental health, and increased odds of HIV acquisition (Jewkes et al. 2010; Decker et al. 2009; Campbell 2002). Yet, beyond its impact on women survivors, IPV also has close ties to concomitant health outcomes among men who commit violence. Men who enact violence against women engage in higher levels of sexual risk behaviours, including inconsistent condom use (Townsend et al. 2011; Raj et al. 2006), transactional sex (Townsend et al. 2011; Dunkle et al. 2006), and casual partnerships (Dunkle et al. 2006). Young men who commit acts of violence against women are more likely to be HIV-positive than non-violent counterparts (Jewkes et al. 2011).

Masculinities and IPV

Public health research focused on violence has increasingly drawn upon concepts from the social sciences, which view masculinity as a social construct that can change over time (Barker 2010; Dworkin, Treves-Kagan, and Lippman 2013; Pulerwitz and Barker 2008). Within an emerging evidence base on the links between masculinity and health, an important distinction is made between hegemonic masculinity - which refers to the most dominant form of masculinity in a given era in a given time - and marginalised and subordinated masculinities (the working class, men of color, the poor) (Connell 1995). While few men might attain the dominant form of masculinity, all men (hegemonic, marginalised and subordinated men) shape their configurations of practice in relation to these norms. Masculinities may be particularly contested in South Africa, where social turbulence and economic transitions frame masculinities within a rapidly-evolving society (Walker 2005; Dworkin et al. 2012).

Within the IPV literature, researchers find strong and consistent links between adherence to hegemonic norms of masculinity and harmful health outcomes. Global research suggests that men who strictly adhere to dominant norms of masculinity (e.g. toughness, virility, power) are more likely to perpetrate IPV (Santana et al. 2006). Elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, strict masculine norms have been suggested as a key social driver of IPV (Hatcher et al. 2013). There is also now a growing understanding that in South Africa, adherence to hegemonic masculinity lead to harmful health behaviours, including alcohol use, risky sex, and IPV (Jewkes and Morrell 2010).

Men who embrace hegemonic forms of masculinity often report harmful alcohol use (Peralta, Tuttle, and Steele 2010; Morojele et al. 2006). South African men who are violent to intimate partners or report rape are more likely to drink heavily, engage in transactional sex, and have large numbers of partners (Dunkle et al. 2006). South African men who abuse alcohol are more likely to report IPV (Gass et al. 2011; Abrahams et al. 2004). Harmful use of alcohol has been strongly associated with the perpetration of IPV in low- and middle-income settings across the globe (Gil-Gonzalez et al. 2006), although considerable debate remains about the causal relationship between alcohol and IPV (Gelles and Cavanaugh 1993).

Norms around risk-taking, virility, and resilience have been associated with risky sex in the form of multiple partnerships, lower condom use, and transactional sex (Nyanzi, Nyanzi-Wakholi, and Kalina 2009; Santana et al. 2006; Townsend et al. 2011). In Botswana and Swaziland, men who adhered to hegemonic norms of masculinity and reported less gender equitable norms were twice as likely to report engaging in forced sex (Shannon et al. 2012). In South Africa, men endorsing traditional male roles were more likely to be dominant in sexual decision-making (Kaufman et al. 2008).

The literature also suggests that men who adhere to hegemonic norms are less likely to report positive mental health and general well-being. In some studies, masculinity has been associated with an avoidance of healthcare – in particular HIV-related care (Skovdal et al. 2011; Lynch, Brouard, and Visser 2010) – as men struggle to be viewed as strong, resilient, and in control. It has become clear that transforming constraining aspects of masculinity has implications for the health and well-being of both women and men (Dworkin et al. 2013; Mankowski and Maton 2010).

Preventing IPV among men

To date, most interventions to reduce IPV perpetration among men exist in high-income countries and are placed within the criminal justice system (Day et al. 2009; Hamilton, Koehler, and Losel 2012). These rehabilitative approaches often target men who have already been convicted of IPV, rely on cognitive, psycho-educational approaches to limit “re-offending”, and seem to have a limited effect on future violence perpetration (Babcock, Green, and Robie 2004; Feder and Wilson 2005). Few programmes addressing IPV are rooted in theories of masculinity, and fewer still examine the effect of hegemonic male norms on IPV perpetration and healthy sexual practices and relationships.

Despite findings that programmes which are “gender transformative”—that seek to change gender roles and create more respectful and egalitarian relationships (Dworkin, Treves-Kagan, and Lippman 2013)—can have a positive impact on gender equality in relationships, little research has examined the extent to which programs may be effective for reducing IPV. One notable exception is Kalichman et al.'s study showing that a brief behavioural intervention reduced men's self-reported use of physical violence towards a partner (Kalichman et al. 2009). A second seminal contribution is Jewkes et al.'s 2008 evaluation of Stepping Stones, a gender transformative curriculum that reduced men's reports of perpetrating IPV and engaging in problem drinking (Jewkes et al. 2008). As illustrated in a review of the literature, most remaining studies that examine how men change in terms of IPV behaviour are based in resource-rich settings (Eckhardt et al. 2006). Moreover, while there are promising results from quantitative findings on gender transformative programmes, the field knows very little about how men change within such programmes.

Methods

To fill the gap in understanding IPV prevention among men, we conducted qualitative research in rural South Africa to explore how a gender transformative programme may have impacted IPV-related health outcomes. We recruited participants from a programme targeting masculinities, HIV risk, and IPV among men of reproductive age. The aim of this research was to understand the mechanisms through which a gender-transformative intervention might improve health behaviours related to IPV.

The Programme

`One Man Can' (OMC), implemented by Sonke Gender Justice Network (Sonke), is a gender-transformative, masculinities and rights-based programme. It attempts to reframe harmful definitions of masculinities in order to attain reduced rates of violence, decreased levels of unsafe sex, and work towards more just and equitable gender relations. OMC workshops are facilitated by men and are held in groups of 15–20 men. OMC was implemented by Sonke in all nine provinces throughout South Africa and has been scaled up to North Sudan, Swaziland, Lesotho, Mozambique, Zambia, and Malawi.

OMC defines masculinity not as a fixed trait but as situational and in-flux. Workshop materials focus on the costs of masculinity, or the negative effects of endorsing dominant norms of masculinity (Courtenay 2000; Messner 1997). OMC aims to work with men to examine the links between gender, power, and health (alcohol use, violence, HIV/AIDS). The OMC curriculum defines and critically evaluates masculinities and how these are practiced in relationships with women, other men, and the broader community. It uses a rights-based approach (focused on concepts of power, equality, and non-discrimination), to reducing violence against women and both women's and men's HIV risks. OMC activities highlight the costs of masculinity, or the negative effects of endorsing dominant norms of masculinity (Courtenay 2000; Messner 1997), and examine the links between masculine norms and negative health outcomes such as alcohol use, health care access, HIV prevention, and intimate partner violence. The programme presses beyond a classic one-shot public health model of small group workshops by pairing workshops with Community Action Team (CATs) to work towards gender equality and health in communities.

Data Collection

We conducted qualitative in-depth interviews with men (n=53) who participated OMC in two rural settings. Qualitative research was deemed appropriate for this research as it aims to unpack an underexplored area of the literature in an exploratory way, allowing the “voices” of participants to help guide new insights and theory development (Lofland and Lofland 1995).

Men were recruited from Eastern Cape (N=26; Mhlontlo Municipality), and Limpopo Province (N=27; Thohoyandau). Inclusion criteria for the current study were: being male, age 18 years or older, having completed OMC workshops no more than six months before the date of recruitment, and residing in communities where Sonke implements OMC. All participants in our sample are Black, South African men, given that this was the target population of OMC at the time and is disproportionately affected by HIV (Dworkin, Hatcher et al. 2013).

Participants were recruited through community partner organisations. Men were interviewed once following programme participation, and interviews took place from February to September 2010. To minimise social desirability bias, we hired three Researchers (the third author, NN, in Eastern Cape, and another in Thohouyandou) who were familiar with the communities of interest but who were external to Sonke.

Semi-structured interviews guides were developed by the authorship team in an iterative fashion. A series of piloting, electronic input, and team meetings (a total of 28 hours) with the authorship team and researchers helped to refine interview topics and ensure that the approach would elicit rich responses from participants. Interview guides focused on topics related to masculinities, gender relations and rights, sexuality, violence, gender and HIV risk, alcohol, fatherhood, and relationships. Researchers were experienced in researching sensitive topics such as gender, masculinities, HIV, and sexuality, and were trained for 3 days in qualitative methods and ethical research practices by the first and last authors. Interviews were carried out in local South African languages (Venda or Xhosa), were transcribed into the local language, and then into English by the researcher.

Ongoing quality control and mentorship was carried out during data collection and included monthly phone calls, transcription reviews and discussion. Participants were offered R100 (about US $12) as reimbursement for time and transportation associated with participation. Interviews lasted between 1 and 2 hours. Research was conducted on the basis of written, informed consent and anonymity was protected in all research outputs. This research protocol was approved by the ethics boards at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and University of California San Francisco, USA.

Qualitative data analysis

The sample size reflects the “30 to 60” metrics for sample size in qualitative interview studies (Morse 2000). While not a universal rule, Morse suggests that samples of this size are often able to achieve adequate saturation and redundancy across relevant characteristics. In order to track the saturation of key themes, researchers wrote structured reflection notes following every interview, which indicated that overlaps began to occur after the mid-point (n=41) in data collection.

For coding and analysis, we drew upon thematic analysis of qualitative data (Lofland and Lofland 1995; Strauss and Corbin 1990). To begin the coding process, two researchers (first and last authors) extracted excerpts of the transcribed interviews that related to shifts in gender ideologies, masculinities, and rights. To establish a codebook, five interviews were randomly selected and independently evaluated using a thematic, structured coding process employed during the initial phase of coding often deployed in qualitative research methods (Lofland and Lofland 1995; Strauss and Corbin 1990). Thematic, structured codes were then coded during a second round to produce secondary, “fine” codes. After a second round of coding, coders held a series of discussions to ensure full refinement of primary and secondary categories (Berg 2004). Once the full range of categories was established, the remaining interviews were double coded independently by the first and last authors. Discrepancies in codes were resolved through discussion and decision trails were kept in order to achieve consistency and accuracy throughout the coding process. Lastly, we wrote analytical memos to capture main themes and to lift multiple sub-codes to a broader thematic analysis (Lofland and Lofland 1995). To facilitate the analysis, the codebook was applied to the data using qualitative analytical software (QSR Nvivo 9).

Quotes presented here are reflective of the cohort or, where noted, contrast the views of other participants. Quotes are presented alongside socio-demographic information, including location (Eastern Cape [EC] or Limpopo [LIM]), age in years, and number of OMC sessions attended. Pseudonyms have been given to protect confidentiality and anonymity of participants.

Descriptive Quantitative Data

Two types of quantitative data complemented the qualitative findings. First, a small set of socio-demographic information were collected from participants. These included age, marital status, education, employment, and number of children. Information around OMC participation included how many OMC sessions the participant attended and whether they were an active CAT member. Second, self-reported outcomes were coded using a dichotomous rubric (0=no self-reported change, 1=has changed beliefs or practice after participation in OMC). This quantification of the qualitative data is used to illustrate the proportion of the cohort that reported changes.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of the 53 men purposively recruited to participate in this research, 55% were unemployed (Table 1). About half were married (51%) and the majority had at least one child (74%). Despite efforts to recruit an equal number of younger and older participants, only 26% of this sample were between 17 and 29 years old. Most participants were between the ages of 31 and 55 years. Participants in this analysis attended an average of 2.7 sessions of OMC workshops, with many (45%) attending 3 or more sessions.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics

| Sample Characteristic N= 53 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | ||

|

|

|||

| Setting | |||

| Eastern Cape | 26 | 49% | |

| Limpopo | 27 | 51% | |

| Employment status | |||

| Unemployed | 29 | 55% | |

| Casual Labor | 7 | 13% | |

| Employed | 15 | 28% | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 22 | 42% | |

| Married | 27 | 51% | |

| Widowed/Divorced | 4 | 8% | |

| Children | |||

| No children | 14 | 26% | |

| 1–2 children | 17 | 32% | |

| 3+ children | 22 | 42% | |

| Age | |||

| 17–29 years | 14 | 26% | |

| 30–55 years | 28 | 53% | |

| 55+ years | 10 | 19% | |

| Sessions attended | |||

| 1–2 sessions | 28 | 53% | |

| 3+ sessions | 25 | 47% | |

Qualitative findings

We sought to understand the impact of a gender-transformative program on IPV-related health outcomes. First, men described new patterns of reduced alcohol intake, often closely linked to shifting ideals of manhood. This finding leads to the second theme of improved partner communication, in which men took on new roles in relationships and households. Communication changes included shifts towards more gender equality in decision-making and more respectful handling of volatile emotional states in ways that did not lead to the escalation of violence. In the third theme, men described sexual decision-making changes in terms of shifting views around sexual entitlement and mutuality on choosing when and whether to have sex. Finally, we examine several excerpts in which men articulate the deeply rooted nature of each of these topics, showing how alcohol and sexual relationship skills are embedded within constructs of manhood and use of violence.

Reduced alcohol use

As shown in Table 2, alcohol reduction emerged as a common interview theme. A majority of younger participants (n=8, 57%) and mid-aged participants (n=15, 68%) reported a reduction in the intake of alcohol after participating in OMC.

Table 2.

Changes reported, by participant age

| Younger (age < 30 years) n= 14 | Mid-aged (age 30–50 years) n= 22 | Older (age 51+ years) n= 17 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | percentage | number | percentage | number | percentage | |

|

|

||||||

| Reduced Alcohol | ||||||

| 8 | 57% | 15 | 68% | 2 | 12% | |

| Improved Partner Communication | ||||||

| 5 | 36% | 9 | 31% | 3 | 18% | |

| Equity in Sexual Decision-making | ||||||

| 1 | 7% | 10 | 45% | 3 | 18% | |

Some men linked alcohol reductions to more equitable decision-making in sexual relationships. For example, one young participant described his choice to return home after a night of drinking with a group of young men, rather than going out to visit various girlfriends:

I have got encouragement from many people as a result of my joining OMC. It has made me a better man because now if I feel I have had enough to drink I go home, as opposed to the earlier habits of going to see girlfriends. That was risky because I was putting myself of unprotected sex and HIV. I have also reduced on the amount of alcohol that I consume [in each sitting]. (Thabo, EC, Age 19, 3 sessions)

In this quotation, and several others, reduced alcohol intake was closely linked to shifting ideals of manhood. In this example, the young man felt his alcohol reduction put him less “at risk” sexually, whereas another, older, participant described how he transitioned from putting himself in danger towards being responsible:

Yes, they [OMC staff] have truly helped me to move from the danger of drinking to being someone responsible. I used to drink everyday and go home drunk and shouting to my children. I really have changed, I have completely stopped drinking. I do not see a reason why I should again find myself in such danger. (Sizwe, LIM, Age 62, 1 session)

For other men, a reduction in alcohol meant that men began caring more for their girlfriends and children – a change that reduced relationship conflict and was satisfying to both men and women:

I was a person that used to like fun and drinking alcohol. I was always out there with the boys drinking. I didn't have time for my girlfriend and my daughter. She would come with my daughter to the tavern and beg me to at least give them attention. Sometimes she would go to my place and find me absent and she would sleep and wait for me. On my arrival, I would get into arguments with her. However after that workshop, I got to understand the importance of care and it has helped me. I am also enjoying it as well. (Siphume, EC, Age 23, 1 session)

Again, the participant's view of himself as a man shifted from “fun” and being “out with the boys” towards being more attentive and caring in his family relationships.

Improved partner communication

Some participants in both younger (n=5, 36%) and mid-aged (n=9, 31%) groups described how OMC improved their communication with partners and heightened levels of respect in handling heated emotions during verbal conflicts. One man described that after attending OMC, he made an increased effort to calm down before speaking with his girlfriend about an upsetting issue:

It changed my own relationship. If my girlfriend is angry with me and even if she is the one that is wrong, I calm down and talk to her without fighting. I respect her and I know that I should not beat her up. She even told me that things have changed in the way I act in our relationship and she is happy about it. (Lesedi, EC, Age 34, 2 sessions)

The intentional decision to view communication as linked to “respect” underscores the ways in which respect is an important route through which men conceive of themselves as men (Dworkin et al. 2012; Messner 1997). These strategies seemed to reduce conflict in his relationship, a factor that he perceived as pleasing to his girlfriend.

Other participants described how a sense of having the “final word” in decision-making previously led to conflict in relationships.

For some, if their partner or wife would tell him of the wrong doings in his life, he would feel like his manhood is being questioned or doubted. The partner may be trying to help at the time but the man would feel as if the wife wants to become the head of the home and make him a laughing stock among other men in the community. Some may end up abusing the women as they would be feeling threatened and take it out on their wives or partners in a physical way. (Dembeza, EC, Age 63, 4 sessions)

In this quotation, the participant seems to show how questioning by a female partner can be construed as a threat to masculinity – undermining a man's status in the community and his household. This threat was noted as sometimes leading to backlash in the form of physical violence.

After participating in OMC, several participants described how they tried out new ways of expressing their manhood in intimate relationships:

In one of my frequent drunken states, I would go and look for my girlfriend and when I wanted her to come along with me there would be no compromise. My word was the final word and I would not take any input from her. Attending the OMC workshops, I got to understand the wrongs of my past behaviour and I started understanding that men should also listen to the woman's inputs. (Khuzani, EC, Age 33, 9 sessions)

In this case, the intersection of alcohol, partner communication, and new ideas around masculinity seemed to modify decision-making dynamics, shifting these from being male-dominated to involve more joint decision-making.

Lastly, several participants noted new forms of loving communication based on an understanding through OMC that men can also express care and affection:

I believed in the old way of doing things that a man should not show his emotions or love openly but OMC changed me because now I can show my girlfriend how much I love her. I tell her that I love and she enjoys the attention and being told that she is loved. (Mandla, EC, Age 41, 10 sessions)

Several participants expressed changes in their relationship with both partners and children, as OMC taught them new ways of communicating openly and emotionally with both children and partners.

More equitable sexual decision-making

Nearly half of participants in the mid-aged group (n=10, 45%), but few in the younger group (n=1, 7%) or older group (n=3, 18%), described increased equity in terms of decision-making around sex and sexuality. An older participant explained that his manhood was not determined by sexual power held over women:

It was one of my fascinations to hear men defining power that people have within the communities, that included sexual power carried by men over women. When I looked at the topic deeply, I then had to search inside me and compare what I do to women as well to influence their decision due to my power…In my culture, an ideal man is the protector and provider of the family. But things have changed now. Even women can protect and provide the family. So there is no longer something like and ideal man. A man is just a man like a human being who can do anything work that can be done in the house, even cooking and laundry. I now know that my manhood or masculinity is not determined by the power I have over women. (Makondelela, LIM, Age 42, 2 sessions)

A younger participant challenged the views of his peer group who perceived that they were entitled to sexual access from female partners. He explained that friends blame a woman for infidelity if she chooses not to have sex, or force sex upon a partner:

I have heard a person say “I beat her up because she did not want to sleep with me. She is my girlfriend and if she does not want to sleep with me it means she has been sleeping with someone”. It is funny because other people see nothing wrong with such statements. I do not agree with that because your partner must also be willing to have it. It is not good to force people to have sex. (Zakhele, EC, Age 27, 1 session)

Several participants described transitioning from multiple partnerships to one committed relationship. For example, one young man explained that his decision to be faithful to one girlfriend coincided with a joint decision to use condoms:

OMC changed me in the relationships that I have with women because I had many girlfriends but after talking to Prince [the OMC Facilitator], I decided to keep one girlfriend. With my girlfriend, we use condoms if we are going to have sex and she agrees as well. (Xolani, EC, Age 28, 1 session)

Reduced violence

Many of the narratives of men who reduced violent behaviour also included multiple, overlapping changes in other health behaviours. For example, after participating in OMC, one young man described significant changes related to reduced intake of marijuana and a new, non-violent identity:

Since the training I received from OMC, I stopped smoking and since I stopped smoking I reduced on violence. I don't know what smoking was doing to me but it made me very violent. I was always involved in fights and I think that is the reason why they invited me to be part of OMC. Since then I have drastically changed. I do not like fighting at all and, as I mentioned earlier, I am now a peacemaker at school. (Dyesha, EC, Age 17, 3 sessions)

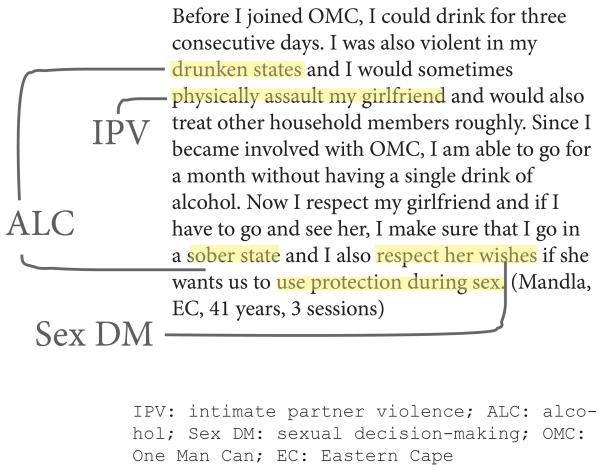

One older man explained that prior to OMC, high levels of alcohol use led to both violence towards his sexual partner and with his family members. After participation in OMC, he often chose to abstain from alcohol. He explains how this personal change led to an improved level of respect and better communication around condom use. As shown in Figure 1, the coding of this excerpt illustrates the inter-connected issues of alcohol, IPV, and sexual decision-making.

Figure 1.

Text coding, Example 1.

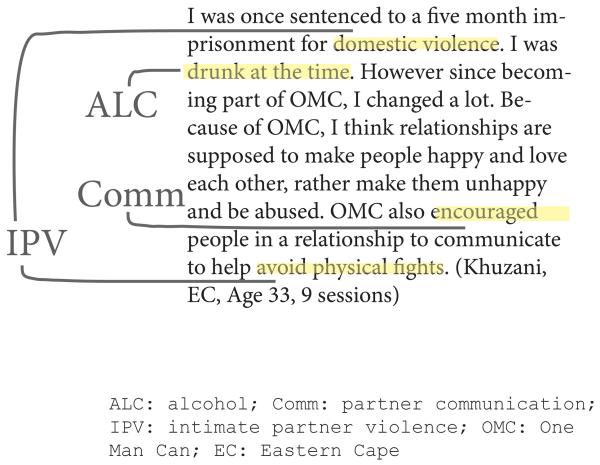

In the second text coding (Figure 2), a participant explains how his alcohol use was associated with a previous stint in prison, but that OMC helped him learn to re-envision his relationship. He expressed satisfaction in using enhanced communication skills to create a caring relationship without the use of physical violence.

Figure 2.

Text coding, Example 2.

Several participants described changes in responding to IPV within the community. An older participant expressed a new desire to take public action around sexual violence as a way to show abusers that men are taking a stand:

When there are cases of woman or children raped, we must not see only women with placards or complaining in public. Men must be seen in numbers to show the abusers that it is not only women's problem but it is our problem as well as men, when our daughter, sisters and wives are abused. (Vhulenda, LIM 03, Age 39, 8 sessions)

Discussion

The current study examined how a gender-transformative programme influenced the lives of 53 men with regards to IPV and related behaviours. Our results reveal that many participants perceived that OMC spurred important shifts in communication and decision-making, which impacted both sexual health and violence-related behaviours. By reducing alcohol consumption, many participants concomitantly improved relationships with their partners and family members, as they became more respectful and better at communicating. Men described that OMC shifted narrow definitions of masculinity (such as decision-making authority, violence, sexual risk-taking) in the direction of joint decision-making and increased respect for partners.

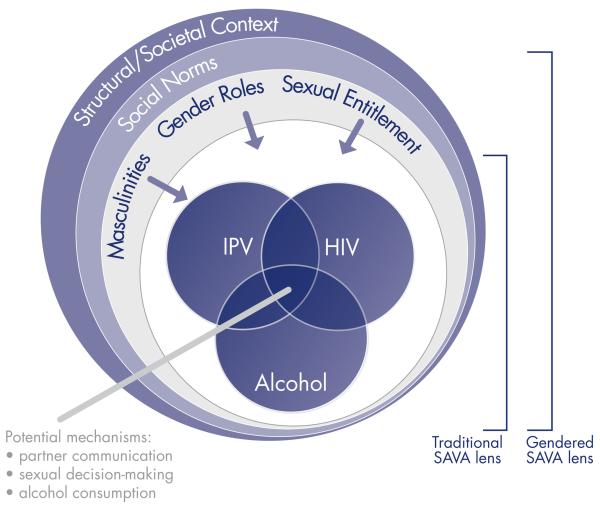

In our study, shifts in one area of a man's life seemed to merge with improvements in other areas. For example, in several interviews, men spoke about alcohol and improved relationships in the same narrative, or redefining masculinity and reducing the number of partners, perhaps suggesting that these changes are synergistic. A clustering of health problems, related to alcohol and substance use, violence, and HIV has been identified as the SAVA syndemic (Singer 2006). SAVA is an acronym originally from medical anthropology used to describe the intersection of the multiple health problems of substance abuse, violence, and AIDS (Singer 1994). By calling SAVA a syndemic, scholars highlight the concurrent, intertwined, and mutually reinforcing nature of multiple health problems that were previously considered discrete or unrelated (Singer and Clair 2003). Originally embraced by scholars working with poor urban women in the USA (Meyer, Springer, and Altice 2011; Gonzalez-Guarda et al. 2011), scholars of low- and middle-income settings have begun draw upon SAVA as a useful tool for understanding these syndemics among women (Russell, Eaton, and Petersen-Williams 2013; Ulibarri et al. 2011). This is the first work, to our knowledge, that has considered the application of SAVA to heterosexual men in a low-income setting. Lessons from our research suggest that OMC has potential to be effective partly because of its ability to engage in multiple, clustered problems in men's lives.

Underpinning many excerpts across our sample was the discussion of how SAVA-related issues were embedded in norms and ideals around manhood. Thus, our data suggest the SAVA syndemic among rural, South African men, may be underpinned by constructs of masculinity (Figure 3). Our findings suggest that masculine norms should be an important focus of future syndemic research. This echoes calls by other scholars, who have noted that IPV prevention should address gendered dynamics such as sexual entitlement, legitimacy of punishment and the use of violence to assert power over women (Jewkes et al. 2011).

Figure 3.

Gendered SAVA syndemic (adapted from Singer, 1996).

Participation in OMC within our sample was limited to an average of 2.7 sessions per person. This represents a shorter intervention than many interventions with men focused on IPV, which often last between 20 and 35 sessions (Scott and Wolfe 2000; Jewkes et al. 2008). However, in South Africa, Kalichman et al. found that a brief 5-session intervention combining HIV and gender-based violence reduced self-reported perpetration of physical IPV (Kalichman et al. 2009). Regardless, it would be optimal to establish a baseline “dosage” of the OMC intervention required to see changes, and in a future quantitative study we plan to explore whether a consistent number of sessions of OMC significantly impact violence-related behaviours. Within contexts of entrenched social norms and broader inequalities, it may be challenging for brief peer education programs like OMC to disrupt IPV-related behaviours. Indeed, the community and societal context are essential to the success of this type of group-based intervention (Campbell 2004), and should be engaged in future programming.

Reduced alcohol intake may be one crucial aspect of sexual health and violence-related behaviours. Our findings around alcohol are consistent with extant literature (Kalichman et al. 2009). However, very few interventions have been tested that merge gender equity or masculinities-based content with reducing alcohol intake to improve sexual risk outcomes, and as such, this is clearly a fertile arena for future research.

Our finding that improved communication and shifts towards more joint decision-making seemed to strengthen participant relationships is consistent with previous literature. For men, the development of new skills and respectful repertoires around communication and decision-making is often an important pre-requisite for IPV-related behaviour change (Scott and Wolfe 2000). Our research suggests that the capacity to communicate respectfully in ways that allow each partner to identify and share feelings and concerns in an open and safe way may prevent IPV, a finding that is consistent with qualitative results from Stepping Stones (Jewkes, Wood, and Duvvury 2010). When men feel unable to retain power in other areas of the relationship, they may use violence as a method for regaining control – particularly in a societal context where the use of violence is seen as a legitimate form of airing grievances (Wood, Lambert, and Jewkes 2008). Others have noted that as rapid economic and social changes threaten the fabric of society, there is a decrease in trust and quality of communication (Hunter 2010). Thus, it is important to note that men alone cannot be responsible for improving communication skills. Reduction in the use of IPV is most likely to occur in the context of both members of the couple acquiring better skills for conflict resolution (Pepler 2012), and when societal norms around the legitimacy of violence as a tool for communication are addressed (Reed et al. 2011).

Our participants expressed that once they critically assessed their previous role of adhering to authoritarian decision-making, they saw that their partners had important insights and skills to offer the relationship. Instead of being threatened by program content in OMC, men viewed their shifts to more gender equality as a positive resource and trait, which increased relationship satisfaction. This is important, since it is not only the attitudes towards women that influence IPV but how a male responds when gender role expectations or authority are challenged (Dworkin et al. 2012). Certainly, one factor found to be related to male perpetration of IPV is the extent to which a relationship adheres to traditional gender roles, in which decision-making is viewed as the primary responsibility of the male partner (Stith et al. 2004). Given these advancements in understanding violence, it is crucial that gender transformative programs shift men towards gender equitable attitudes for the reduction of violence and reduced risk behaviours (Pulerwitz and Barker 2008).

Limitations

This research should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, although our researchers were trained to ensure confidentiality and slowly “peel back” layers of meaning for participants, it is possible that men's narratives were shaped by social desirability bias. This may be especially true following a programme during which men were sensitised to reconfiguring norms of masculinity. Although interviews were conducted by male, Black, South African researchers who grew up in the same rural areas as participants, it is possible that age, class, or other power differentials may have limited the openness of discussions. Second, as an exploratory, qualitative study, our findings cannot conclude whether attitudinal or behavioural changes definitively occurred. One challenge of applying quantitative descriptor data to qualitative interviews is that – unlike structured questionnaires – men may not report on changes for various reasons (they made no change; they were never asked; they were unclear about the change made). It will be beneficial for future studies to integrate both qualitative and quantitative evaluation tools (Dworkin, Treves-Kagan, and Lippman 2013). Third, as with most qualitative research, the data is not representative and men who participated in OMC may be different from counterparts choosing not to participate. Another limitation to representativeness is that our sample was comprised of Black men from marginalised rural and peri-urban areas. Thus, lessons from this research may need to be tempered given that other South African settings may have a distinct racial or class composition. Lastly, because we did not corroborate findings based on female partner's perspectives, it is not possible to conclude whether the changes described were substantive in relationships or sustained over time. In the future, a dyadic, relational analysis may be promising for understanding complex relational shifts, as opposed to single-sex analysis (Dworkin et al. 2011).

Metrics for “change” are challenging in any qualitative analysis. Given that these interviews were carried out among men after OMC participation and we do not have baseline assessments, we were careful in our assessment of “changes” in masculinities. In our analysis, we attributed changes in gendered norms, practices, and masculinities only when men stated that these had changed because of their involvement in OMC. Despite methodological challenges, our qualitative findings could contribute to theorising the mechanisms of change within OMC, now seen as a key component of evaluating complex public health interventions (Bonell et al. 2012).

Conclusions

These findings have several practical implications for future work with heterosexual men in low- and middle-income settings. First, future programs may be able to target IPV-related behaviours among men, shown in our setting to include reduced alcohol use, improved partner communication, and share decision-making power. Second, our findings suggest that men can be interested and engaged in participating in programs that address meaningful issues in their lives. Lastly, the insight of syndemics may be useful not only for understanding multiple health challenges, but for crafting responsive solutions. Integrating the concept of gender into SAVA literature may be useful, since masculinity is deeply intertwined with men's use of alcohol, violence, and their risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV. We posit that future programmes may require a gendered SAVA lens if they are to be effective in shifting men's health outcomes and addressing IPV among men.

References

- Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Hoffman M, Laubsher R. Sexual violence against intimate partners in Cape Town: prevalence and risk factors reported by men. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(5):330–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Green CE, Robie C. Does batterers' treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;23(8):1023–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker G. Reconceiving the second sex: Men, masculinity and reproduction. Global Public Health. 2010;5(6):679–681. [Google Scholar]

- Barker G, Contreras JM, Heilman B, Singh AK, Verma RK, Nascimento M. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Vol. 5. Pearson Boston: 2011. Evolving Men: Initial Results from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES. Washington,D.C.: International Centerfor Research on Women (ICRW) and Instituto Promundo. Berg, Bruce Lawrence. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bonell C, Fletcher A, Morton M, Lorenc T, Moore L. Realist randomised controlled trials: a new approach to evaluating complex public health interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Catherine Creating environments that support peer education: experiences from HIV/AIDS-prevention in South Africa. Health education. 2004;104(4):197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Masculinity and Globalisation. Men and Masculinities. 1995;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(10):1385–401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day Andrew, Chung Donna, O‚ÄôLeary Patrick, Carson Ed. Programs for men who perpetrate domestic violence: an examination of the issues underlying the effectiveness of intervention programs. Journal of family violence. 2009;24(3):203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, Seage GR, 3rd, Hemenway D, Raj A, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Silverman JG. Intimate partner violence functions as both a risk marker and risk factor for women's HIV infection: findings from Indian husband-wife dyads. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(5):593–600. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a255d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Mak JY, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, Lim S, Bacchus LJ, Engell RE, Rosenfeld L, Pallitto C, Vos T, Abrahams N, Watts CH. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340(6140):1527–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1240937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Khuzwayo N, Koss MP, Duvvury N. Perpetration of partner violence and HIV risk behaviour among young men in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. Aids. 2006;20(16):2107–2114. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247582.00826.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Treves-Kagan S, Lippman SA. Gender-Transformative Interventions to Reduce HIV Risks and Violence with Heterosexually-Active Men: A Review of the Global Evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2845–63. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Colvin C, Hatcher A, Peacock D. Men's Perceptions of Women's Rights and Changing Gender Relations in South Africa Lessons for Working With Men and Boys in HIV and Antiviolence Programs. Gender & Society. 2012;26(1):97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Dunbar MS, Krishnan S, Hatcher AM, Sawires S. Uncovering Tensions and Capitalizing on Synergies in HIV/AIDS and Antiviolence Programs. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(6):995. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.191106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin Shari L, Hatcher Abigail M, Colvin Chris, Peacock Dean. Impact of a gender-transformative HIV and antiviolence program on gender ideologies and masculinities in two rural, South African communities. Men and Masculinities. 2013;16(2):181–202. doi: 10.1177/1097184X12469878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI, Murphy C, Black D, Suhr L. Intervention programs for perpetrators of intimate partner violence: conclusions from a clinical research perspective. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(4):369–81. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder Lynette, Wilson David B. A meta-analytic review of court-mandated batterer intervention programs: Can courts affect abusers' behavior? Journal of experimental Criminology. 2005;1(2):239–262. [Google Scholar]

- Fulu Emma, Warner X, Miedema S, Jewkes R, Roselli T, Lang J. Findings from the UN Multi-country study on men and violene in Asia and the Pacific. UNDP, UNFPA, UN Women, UNV; Bangkok: 2013. Why do some men use violence against women and how can we prevent it? [Google Scholar]

- Gass JD, Stein DJ, Williams DR, Seedat S. Gender differences in risk for intimate partner violence among South African adults. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(14):2764–89. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelles Richard J, Cavanaugh Mary M. Alcohol and other drugs are not the cause of violence. Current controversies on family violence. 1993:182–196. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Gonzalez Diana, Vives-Cases Carmen, Alvarez-Dardet Carlos, Latour-Perez Jaime. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: do we have enough information to act? The European Journal of Public Health. 2006;16(3):278–284. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda Rosa Maria, Vasquez Elias P, Urrutia Maria T, Villarruel Antonia M, Peragallo Nilda. Hispanic women,Äôs experiences with substance abuse, intimate partner violence, and risk for HIV. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2011;22(1):46–54. doi: 10.1177/1043659610387079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton Leah, Koehler Johann A, Losel Friedrich A. Domestic violence perpetrator programs in Europe, part I: a survey of current practice. International journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0306624X12469506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher AM, Romito P, Odero M, Bukusi EA, Onono M, Turan JM. Social context and drivers of intimate partner violence in rural Kenya: implications for the health of pregnant women. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(4):404–19. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.760205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter Mark. Love in the time of AIDS: inequality, gender, and rights in South Africa. Indiana University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Morrell R. Gender and sexuality: emerging perspectives from the heterosexual epidemic in South Africa and implications for HIV risk and prevention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13(6) doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Dunkle K, Puren A, Duvvury N. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y, Morrell R, Dunkle K. Gender inequitable masculinity and sexual entitlement in rape perpetration South Africa: findings of a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e29590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y, Morrell R, Dunkle K. The relationship between intimate partner violence, rape and HIV amongst South African men: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Wood K, Duvvury N. `I woke up after I joined Stepping Stones': meanings of an HIV behavioural intervention in rural South African young people's lives. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(6):1074–84. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Clayford M, Arnolds W, Mxoli M, Smith G, Cherry C, Shefer T, Crawford M, Kalichman MO. Integrated gender-based violence and HIV Risk reduction intervention for South African men: results of a quasi-experimental field trial. Prev Sci. 2009;10(3):260–9. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0129-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MR, Shefer T, Crawford M, Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC. Gender attitudes, sexual power, HIV risk: a model for understanding HIV risk behavior of South African men. AIDS Care. 2008;20(4):434–41. doi: 10.1080/09540120701867057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofland J, Lofland L. Analyzing social settings: a guide to qualitative observation and analysis. 3rd edition Wadsworth; Belmont, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch I, Brouard P, Visser M. Constructions of masculinity among a group of South African men living with HIV/AIDS: reflections on resistance and change. Cult Health Sex. 2010;12(1):15–27. doi: 10.1080/13691050903082461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankowski ES, Maton KI. A community psychology of men and masculinity: historical and conceptual review. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;45(1–2):73–86. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9288-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner MA. Politics of masculinities: Men in movements. Vol. 3. Sage Publications, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Jaimie P, Springer Sandra A, Altice Frederick L. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: a literature review of the syndemic. Journal of Women's Health. 2011;20(7):991–1006. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morojele NK, Kachieng'a MA, Mokoko E, Nkoko MA, Parry CD, Nkowane AM, Moshia KM, Saxena S. Alcohol use and sexual behaviour among risky drinkers and bar and shebeen patrons in Gauteng province, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(1):217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse Janice M. Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10(1):3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nyanzi S, Nyanzi-Wakholi B, Kalina B. Male Promiscuity The Negotiation of Masculinities by Motorbike Taxi-Riders in Masaka, Uganda. Men and Masculinities. 2009;12(1):73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pepler D. The development of dating violence: what doesn't develop, what does develop, how does it develop, and what can we do about it? Prev Sci. 2012;13(4):402–9. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0308-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta Robert L, Tuttle Lori A, Steele Jennifer L. At the intersection of interpersonal violence, masculinity, and alcohol use: The experiences of heterosexual male perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Violence against women. 2010;16(4):387–409. doi: 10.1177/1077801210363539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Barker Gary. Measuring attitudes towards gender norms among young men in Brazil: Development and psychometric evaluation of the GEM scale. Men and Masculinities. 2008;10:322–338. [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Santana MC, La Marche A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Silverman JG. Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1873–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed E, Silverman JG, Raj A, Decker MR, Miller E. Male perpetration of teen dating violence: associations with neighborhood violence involvement, gender attitudes, and perceived peer and neighborhood norms. J Urban Health. 2011;88(2):226–39. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9545-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell Beth S, Eaton Lisa A, Petersen-Williams Petal. Intersecting epidemics among pregnant women: alcohol use, interpersonal violence, and HIV infection in South Africa. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2013;10(1):103–110. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0145-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana MC, Raj A, Decker MR, La Marche A, Silverman JG. Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. J Urban Health. 2006;83(4):575–85. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott Katreena L, Wolfe David A. Change among batterers examining men's success stories. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15(8):827–842. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Leiter K, Phaladze N, Hlanze Z, Tsai AC, Heisler M, Iacopino V, Weiser SD. Gender inequity norms are associated with increased male-perpetrated rape and sexual risks for HIV infection in Botswana and Swaziland. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e28739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. AIDS and the health crisis of the U.S. urban poor; the perspective of critical medical anthropology. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(7):931–48. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer Merill, Clair Scott. Syndemics and Public Health: Reconceptualizing Disease in Bio-Social Context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2003;17(4):423–441. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer Merrill. A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS, part 2: Further conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology. 2006;34(1):39. [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal Morten, Campbell Catherine, Madanhire Claudius, Mupambireyi Zivai, Nyamukapa Constance, Gregson Simon. Masculinity as a barrier to men.Äôs use of HIV services in Zimbabwe. Globalization and health. 2011;7(13):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Smith DB, Penn CE, Ward DB, Tritt D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;10(1):65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Vol. 15. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend L, Jewkes R, Mathews C, Johnston LG, Flisher AJ, Zembe Y, Chopra M. HIV risk behaviours and their relationship to intimate partner violence (IPV) among men who have multiple female sexual partners in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):132–41. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulibarri MD, Strathdee SA, Ulloa EC, Lozada R, Fraga MA, Magis-Rodriguez C, De La Torre A, Amaro H, O'Campo P, Patterson TL. Injection drug use as a mediator between client-perpetrated abuse and HIV status among female sex workers in two Mexico-US border cities. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):179–85. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9595-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker L. Men behaving differently: South African men since 1994. Cult Health Sex. 2005;7(3):225–38. doi: 10.1080/13691050410001713215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wood Kate, Lambert Helen, Jewkes Rachel. Injuries are beyond love: Physical violence in young South Africans' sexual relationships. Medical anthropology. 2008;27(1):43–69. doi: 10.1080/01459740701831427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]