Abstract

Hybrid HA/Ge hydrogel particles are embedded in a secondary HA network to improve their structural integrity. The internal microstructure of the particles is imaged through TEM. CSLM is used to identify the location of the Ge molecules in the microgels. Through indentation tests, the Young’s modulus of the individual particles is found to be 22 ± 2.5 kPa. The overall shear modulus of the composite is 75 ± 15 Pa at 1 Hz. The mechanical properties of the substrate are found to be viable for cell adhesion. The particles’ diameter at pH = 8 is twice that at pH = 5. The pH sensitivity is found to be appropriate for smart drug delivery. Based on their mechanical and structural properties, HA–Ge hierarchical materials may be well suited for use as injectable biomaterials for tissue reconstruction.

Keywords: cell adhesion, hierarchical networks, hybrid microgels, smart drug delivery, tissue engineering

1. Introduction

Microgels are small, sub-micrometer polymeric particles. Natural biopolymer microgels are being investigated for numerous biomedical applications.[1,2] Their biocompatibility, along with their large surface-to-volume ratio and their availability in particle sizes ranging from tens of nanometers to several micrometers make them attractive for drug delivery and tissue engineering applications. The three-dimensional internal structure of these microgels has led to their successful application for the storage and transportation of therapeutic macromolecules. The presence of functional groups, such as hydroxy and carboxy groups within the body and on the surface of these microscale structures increases their conjugation properties.[3] Microgels exhibit a fast response to environmental signals and stimuli, unlike bulk gels.[4–7] One of the disadvantages of microgels is their poor mechanical and structural integrity for use as a scaffold in tissue engineering applications.

Hyaluronic acid (HA) has been used for the fabrication of microgels for various biomedical applications.[8–12] A linear polysaccharide formed by units of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and glucuronic acid, HA is found in almost all biological fluids and tissues. The viscoelastic properties of HA-based hydrogels make them useful as injectable biomaterials and tissue fillers. Most importantly, their anti-inflammatory properties make them ideal candidates for wound healing and tissue engineering of organs such as the heart, blood vessels, and vocal folds.[13–16] HA has a simple and homogeneous molecular structure. HA can regulate cell migration and proliferation.[17] The simple chemical composition of HA molecules implies a lack of essential functional groups to interact with other macromolecules and cell surface receptors. Postnatal cells, for example, do not adhere well to HA substrates.[18–21] In HA-based hydrogels some of the available functional groups are already crosslinked, thereby exacerbating the lack of available functional groups. This limitation, however, may be compensated by combining HA with other materials. Polypeptides are strong candidates for biomimetic scaffold design.[22,23] The incorporation of polypeptides in hydrogel networks is important for controlling cellular function.[24]

Gelatin (Ge) is a denatured collagen with many functional groups, such as glycine, proline, glutamic acid, arginine, aspartic acid, leucine, valine, isoleucine, serine, lysine, and threonine. The cell adhesion properties of Ge are regulated by arginine–glycine–aspartic acid (RGD) amino acid sequences, which are recognized by nearly one-half of all known integrins for cell adhesion.[25–27] In three-dimensional cell cultures, the incorporation of natural proteins into the hydrogel network has been shown to support complex cellular functions better than short amino acid sequences.[24] This is why Ge was used instead of RGD.

At temperatures below 35 °C, Ge has a triple-helix structure similar to that of collagen at low temperatures, which may promote physical bonds to create a gel network.[28] The intermolecular structure of the Ge molecule changes at higher temperatures, undergoing a helix-to-coil transition. The responsiveness of Ge-based hydrogels to temperature and pH changes, along with their other properties, makes them excellent candidates for drug delivery, gene delivery, and tissue engineering.[29–36]

In order to achieve substantial mechanical and chemical stability, single strand chains of Ge molecules must crosslink.[37] Crosslinked microgels have been investigated as injectable biomaterials.[38] Doubly crosslinked HA networks have been shown to feature reinforced mechanical properties.[3]

The basic idea of the present study was to combine HA and Ge in order to achieve a biomimetic and functional injectable biomaterial.[39] This possible opportunity has so far been ignored in previous studies, to the knowledge of the authors. Hence, the purpose of the present study was to fabricate HA–Ge-based hybrid microparticles embedded and crosslinked in a secondary HA-based network. A schematic of the constituents and the resulting materials is shown in Figure 1. Thiol-modified HA and thiol-modified Ge polypeptides were assembled in a hierarchical network, crosslinked with poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA). The fabrication procedures and the experimental characterization of the HA/Ge composites are discussed in the following sections.

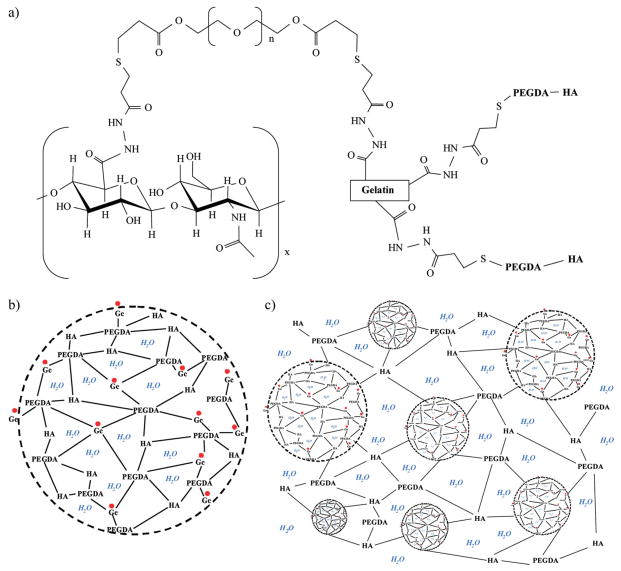

Figure 1.

a) Schematic of thiol-modified HA and Ge crosslinked by PEGDA.[27] b) Microparticle of crosslinked HA and Ge. c) Hierarchical network of HA–Ge microgels with HA network in water.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Thiolated HA (CMHA-S or Glycosil, M̄n ≈ 200 kDa, thiolatation: 40% of carboxy groups), thiolated Ge (Gtn-DTPH or Gelin-S, M̄n ≈ 25 kDa, thiolatation: 40% of carboxy groups), and PEGDA (M̄w ≈ 3400 g mol−1) were purchased from Glycosan Biosystems, Inc. (Salt Lake City, UT). Dioctyl sulfosuccinate sodium salt (Aerosol OT, AOT, 98%), 2,2,4-trimethylpentane (isooctane, anhydrous), heptan-1-ol (1-HP), fluorescamine, monobromobimane (mBBr), acetonitrile, acetone, and isopropyl alcohol were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Atomic force microscope colloidal probes with silicon nitride cantilevers and polystyrene particles attached were purchased from Novascan Technologies Inc. (Ames, IA, USA).

2.2. Microgel Fabrication

A solution of 0.5% thiol-modified HA and thiol-modified Ge was prepared. A mixture of HA and Ge solutions with a volume ratio of HA/Ge = 3 was used as a liquid phase. The solution was injected into an organic phase comprising 0.25 M AOT and 0.05 M 1-HP in isooctane (volume ratio of organic phase/liquid phase of 15). The mixture was stirred at 12 000 rpm for 1 h in order to improve the homogeneity of the emulsion solution. Subsequently, PEGDA (weight of crosslinker/volume of liquid phase = 250 mg mL−1) was added to the solution to induce covalent chemical bonding between the HA and Ge molecules. To disperse the crosslinker and solidify the microgel particles, the tube was vortexed at 12 000 rpm for 3 h at room temperature. The resulting microgels were precipitated in acetone. The particles were agglomerated with a centrifuge at 14 000 rpm for 30 min. The particles were washed several times with acetone and isopropyl alcohol, and then centrifuged to remove any excess surfactants and co-surfactants from the surface.

2.3. Swelling Ratio Measurements

In order to measure the swelling ratio, the particles were freeze-dried and weighed. Distilled water was then added to a vial containing the particles. The excess water was removed by centrifuging. The weight of the wet particles was then measured. The swelling ratio was calculated as the ratio of the weights of wet and dried particles. Two samples were used to measure the swelling ratio. The procedure was repeated three times for each sample.

2.4. Microgel Diameter, Surface Charge, and pH Responsiveness

The particle size, distribution, and zeta potential were measured using a commercially available instrument (Zeta-Plus, Brookhaven, NY). Three microgel samples were dispersed in de-ionized water for surface potential measurements. All the samples were filtered using a syringe filter with a pore size of 3 μm before particle size and zeta potential measurements. For each sample, the zeta potential measurement was repeated ten times and the mean and standard deviation were calculated. The final result reported is the average surface potential for the three samples. The particle size was determined from five consecutive measurements for each sample. The pH-sensitivity was assessed by measuring the effective diameter for different pH values with a constant ionic strength. The diameter change is an indication of the swelling of the particles in response to pH changes. In order to avoid aggregation, especially for low pH values, the particles were dispersed by a sonicator in a water bath (Cole–Parmer Instrument Company, 44 kHz) between measurements.

2.5. Electron Microscopy

A Hitachi S-4700 field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) at an operating voltage of 12 kV, a current of 9 μA, and a working distance of 5 mm was used to characterize the topography of the particles. The particles were first rapidly frozen by immersing the centrifuge tube in a liquid nitrogen container. The frozen particles were then vacuumed using a freeze-dryer, and the dried particles were deposited on an aluminum stub, coated with a very thin layer of gold/palladium (on the order of 10 nm). The gold/palladium layer was sputtered on the surface by a sputter coater for 1 min in preparation for scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of the internal structure of the particles was performed using a Philips CM200 200 kV TEM. An accelerating voltage of 200 kV was used to obtain bright field images. An aliquot of microgel suspension in acetone was placed on a Cu TEM grid with a carbon film. Samples were allowed to dry at room temperature and were subsequently observed by TEM.

2.6. Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy (CSLM)

A Zeiss LSM410 laser-scanning confocal microscope was used to detect Ge in the structure of the particles and to verify the presence of thiol groups on the surface of the microgel.

The purpose of the first experiment was to verify whether Ge was trapped inside the structure. The particles were buffered in a borate solution (pH = 9) for 1 h prior to staining with a fluorescent dye. Fluorescamine was used as the fluorescent dye for protein detection. This dye is very sensitive to primary protein amines. The products of the reaction of this reagent with proteins are highly fluorescent, whereas the reagent and its degradation products are non-fluorescent.

The second experiment was designed to show the crosslinkabilty of the microgels in the secondary network through the thiol groups. A thiol reactive fluorescent dye, mBBr, was used to detect the presence of the free thiol groups that remained on the surface of the particles for further crosslinking. The dye is non-fluorescent until conjugated with thiols. Firstly, 10 mg of mBBr were dissolved in 1 mL of acetonitrile. A 0.1 mL aliquot of the solution was then added to a 1 mL solution of HA–Ge particles in a phosphate buffer solution. The final solution was stirred for 1 h. The solution was centrifuged and washed with water to remove excess reagent before CSLM imaging.

2.7. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Force Measurements

Experiments were performed using a Veeco NanoScope V Atomic Force Microscope. microscope glass slides used as a substrate, were first cleaned and treated with oxygen plasma for better adhesion. In order to avoid dehydration and capillary interferences, all AFM measurements were performed in distilled water and at room temperature. Microgel samples were deposited on a microscope glass slide. A few drops of water were added carefully with the particles attached to the substrate. The deflection sensitivity of the piezo module was established by probing the hard surface of the glass substrates. A thermal tuning method was used to calculate the spring constant of the cantilever beam of the AFM probe. The resulting spring constant value was found to be 0.0972 N m−1. A colloidal probe was used. The diameter of the polystyrene colloidal particle attached to the AFM cantilever was 1 μm. Several hydrogel particles with different sizes were indented. A ramp displacement with a frequency of 1 Hz was applied and the resulting force was processed.[40] The AFM was equipped with a light microscope that could be focused on the surface or the back of the cantilever beam. Microgel particles were viewed and then centered in the field of view before the AFM tip was engaged in contact mode.

2.8. Fabrication of Composite Hydrogel

The HA–Ge particles were filtered using a syringe filter with a pore size of 3 μm to eliminate very large particles. The HA–Ge particles were dissolved in a 0.5% thiolated HA solution. The ratio of the dry particle weight to the volume of thiolated HA solution was 2.5 mg mL−1. The microparticles were dispersed using a sonicator operated at 44 kHz for 10 min. Finally, particles were crosslinked with thiolated HA molecules by adding the PEGDA crosslinker (50 mg mL−1).

2.9. Viscoelastic Characterization of Composite Hydrogel

A Bohlin CVO 120 controlled stress rheometer (Malvern Instruments) was used to measure the elastic shear and loss properties of the gel at room temperature. Parallel plates with a diameter of 40 mm and a gap of 200 μm were used to measure the rheological properties. The distance between the two plates was calibrated before the measurements. The samples were prepared in syringes and were injected to properly fill the gap between the plates. The sample was surrounded by water in order to prevent dehydration. An amplitude sweep was performed to determine the shear stress range over which the deformation was linearly elastic. The accuracy of the stress-controlled rheometer at higher frequencies was limited by the resonance frequency of the device and the sample.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hybrid HA–Ge Microgels

The hydrogel microparticles were fabricated through the copolymerization of HA, Ge, and PEGDA using a standard “water in oil” miniemulsion polymerization technique. The details of the fabrication process are described in the experimental section. The mean swelling ratio of the particles was measured to be 10.5 with a standard deviation of 0.77. The measured swelling ratio may be overestimated because of water entrapment in the densely packed microgels after centrifugation.

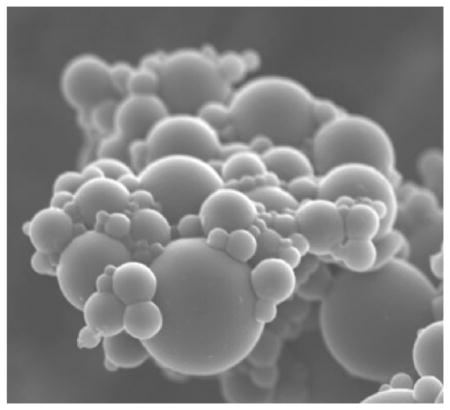

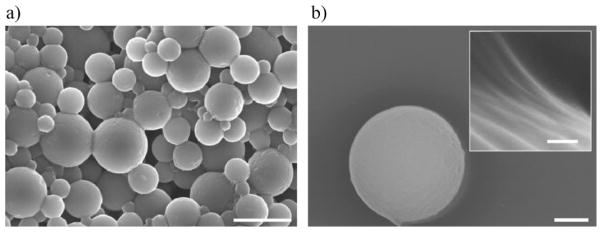

Figure 2 shows an SEM images of the topography of the HA–Ge-based particles. The inverse miniemulsion of the HA and Ge solution in an Aerosol OT (AOT)-based organic phase resulted in stable spherical particles. The PEGDA crosslinker was found to be effective in the polymerization, the solidification of the particles, and the formation of the three-dimensional microgel network.

Figure 2.

SEM of synthesized HA–Ge particles at different magnifications. a) Cluster of particles (scale bar: 5 μm), and b) a single particle (scale bar: 500 nm). The particles are spherical with a smooth surface. The concentrated electron beam from the SEM caused wrinkles on the surface during prolonged imaging. The inset shows the surface of the particle with the micellar structure after electron bombardment which resulted in particle shrinkage. The scale bar in the inset is 100 nm.

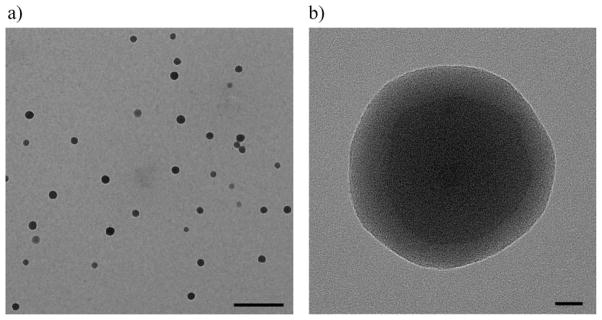

TEM images of the internal structure of the fabricated HA–Ge microparticles are shown in Figure 3. The fabricated microgels exhibit a continuous crosslinked network, as shown in Figure 3b. There are two distinguishable regions of dark and gray for which the electron density is different. The outer section of the particle might be the hairy part of the micelle, with a thickness of 20 nm.

Figure 3.

a) TEM image of filtered particles suspended in acetone and air-dried. The scale bar is 500 nm. The particles were significantly shrunk in the absence of water. b) Magnified TEM picture of a hybrid HA–Ge particle. The original size of the particle in water was around 800 nm. The scale bar is 20 nm.

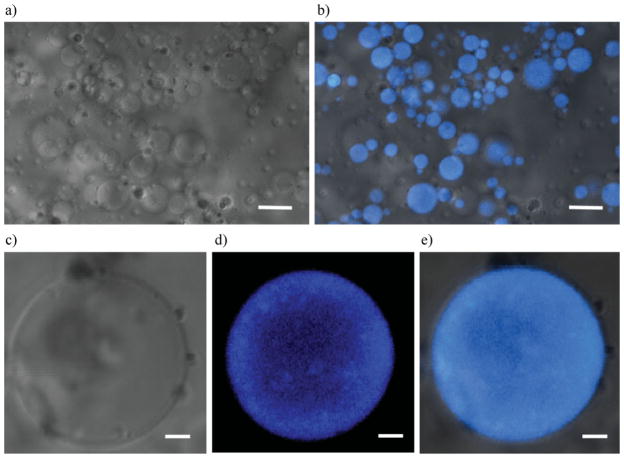

A laser-scanning confocal microscope was used to detect Ge in the particle structure after staining the microgels with fluorescamine. Figure 4 shows the location of Ge molecules inside the microgel. Fluorescence indicates Ge amino groups, while the bright field indicates HA–Ge particles. It is apparent from the CSLM images that Ge is distributed over the surface and throughout the particles. These results support those of a previous study in which Ge molecules were used as a microemulsion stabilizer for drug delivery devices.[41] The same study indicated that Ge molecules acted as a surfactant on the amphiphilic surface of the water droplets. Increasing the amount of Ge caused the molecules to be also found in the water bath of the microparticles.

Figure 4.

CLSM of the HA–Ge particles stained with fluorescamine to illuminate the location of Ge in the intraparticle structure: a) bright field image, and b) fluorescent image of the particles superimposed on the bright field image. c) Bright field and d) fluorescent images of a single particle. e) Superimposed image of fluorescent and bright field pictures (c and d). The scale bar for (a) and (b) is 5 μm, and for (c) (d), and (e) is 1 μm.

Ge molecules were identified throughout the microparticle. These trends indicate that a three-dimensional crosslinked copolymer of HA, Ge, and PEGDA appears to form either a grafted or a random structure. Dense HA–Ge particles with an almost uniform and random distribution of HA and Ge were the designed outcome as they are postulated to promote cell adhesion over long time periods.

The presence of Ge molecules yields characteristics similar to collagen, which is the most important constituent of human tissue.[42] The length and the thickness of semiflexible collagen macromolecules make it difficult to assemble collagen fibers into nanoparticles or small microparticles. Collagen fibers may transmit pathogens and display antigenicty or hypersensitivity.[43] The use of Ge as denatured collagen ensures viability without immunogenicity in tissue engineering.[34] Furthermore, Ge molecules are flexible and can easily be self-assembled to form nanostructures.

The surface electrochemistry of the particles was investigated. The surface potential of the hybrid microgel in deionized water was −4.5 mV, with a standard deviation of 1.6 mV. The distribution of the effective particle diameter, measured by laser light scattering, was found to have a mean value of 1313 nm, with a standard deviation of 145 nm, and a half-width of 872 nm.

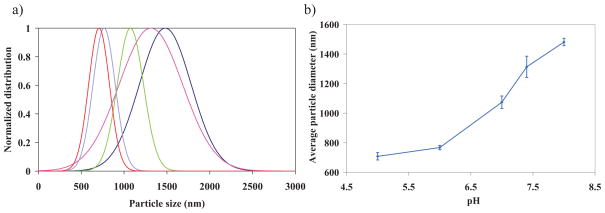

Microgel particles containing ionic co-monomers clearly exhibit pH-responsive behavior. Figure 5 shows the effective diameter of the particles as a function of pH value. While HA has acidic groups, such as carboxy (COOH) groups, Ge molecules are zwitterionic, carrying both acidic (COOH) and basic groups (NH2). These groups are pH-responsive and may alter the osmotic pressure inside the HA–Ge microgels by regulating the mobility of the counter-ions within the particles. By increasing the pH value, COOH groups become more ionized and attract counter-ions that exert a greater osmotic pressure, thereby causing the HA–Ge microgels to swell. The pH-dependent behavior of the hydrogel microparticles is a result of the interactions between moieties and carboxyl groups. A monotonic increase in swelling with pH ranging from 5 to 8 indicates a prominence of acidic groups over amino groups, the latter trying to neutralize the counter-ions needed to balance the excess COO− groups. The molar ratio of Ge molecules is much lower than that of HA molecules. The molar ratio of anionic to cationic residues may be changed by increasing the amount of Ge. This leads to a change in the isoelectric point, and controls the volume phase transition and the shrinkage range of pH values. Microgels are colloidally stable and do not aggregate because of electrostatic and steric interactions. For pH values near the isoelectric point, the particles undergo less repulsive forces, and van der Waals attraction forces may dominate the repulsive forces. In this case, particles are susceptible to aggregation and the colloid is not stable.[44,45] Ultrasound was applied at low pH values to decrease the probability of aggregation and improve the accuracy of the results.[45]

Figure 5.

a) Normalized particle size distribution based on intensity for different pH values with constant ionic strength. From right to left, Dark blue line pH = 8; pink line pH = 7.4; green line pH = 7; blue line pH = 6; red line pH = 5. b) Variation of average particle diameter as a function of pH. The error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean value.

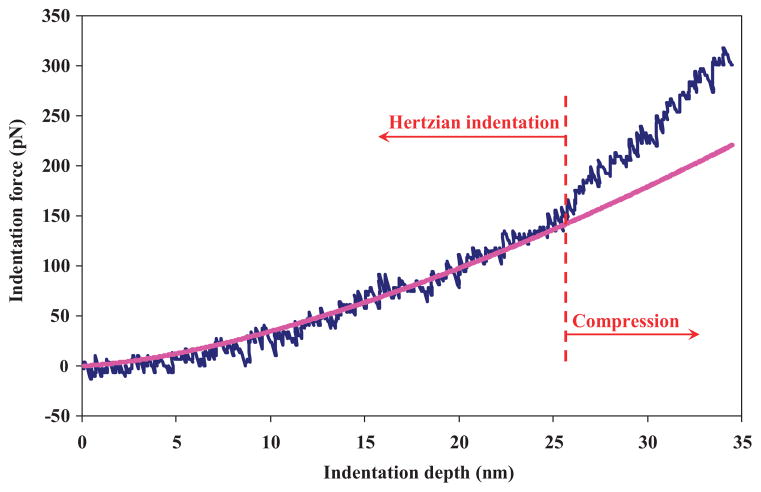

The mechanical properties of the particles were investigated using AFM. Indentation of very soft particles requires the capture of forces in the range of pN.[46,47] Figure 6 shows a plot of the measured force versus indentation depth for a 1 μm sized hydrogel particle. A Hertzian model was used to estimate the elastic modulus of the microgel shell. The regression of data was performed over the first 25 nm of the indentation range, where the assumption of linear elasticity is valid.[48–50] The relationship between the indentation force, F, and the indentation depth, δ, for two spherical solids is:[51]

Figure 6.

Indentation response of a 1 μm sized HA–Ge particle obtained by AFM. The experiments were carried out under water and at room temperature. The Hertzian indentation model regressed over the first 25 nm, where the shell of the particle obeys linear elasticity. The Poisson’s ratio of the sample particle was assumed to be 0.5, the effective contact radius was 1 μm, and the calculated Young’s modulus was 22 kPa. Dark Blue: indentation force (pN); pink line: Hertz force (pN).

| (1) |

where

| (2) |

and E is the elastic modulus, ν is the Poisson’s ratio of the sample particle, R is the effective contact radius, and R1 and R2 are the radii of the two contacting solids, i.e., the AFM tip and the hydrogel particle.

It is challenging to distinguish the exact point of contact in an AFM force curve. However, it is well accepted that in case of negligible adhesion, the contact starts when the AFM cantilever registers a repulsion (positive) force.[52] Based on the AFM force curves, a very small adhesion was observed, and therefore, the contact was assumed to occur at the beginning of the repulsive regime.

The results indicate that the average Young’s modulus of the particle is 22 ± 2.5 kPa. This calculated value is an estimate of the stiffness of the particle shell. For indentation depths δ > 25 nm, the particles are compressed rather than indented, as shown in Figure 6. The slope of the indentation force increases as the indention depth is increased beyond 25 nm. Such an increase in the slope indicates that the overall stiffness of the particles is much greater than the value of 22 kPa calculated for the shell. It is also known that for thin deformable materials, indentation is limited to depths less than 10–20% of thickness of the sample.[52] Beyond this region, the influence of the substrate should be considered in the formulations. Further modeling (e.g., finite element modeling) is required to estimate the Young’s modulus of the microgel for large indentation depths.

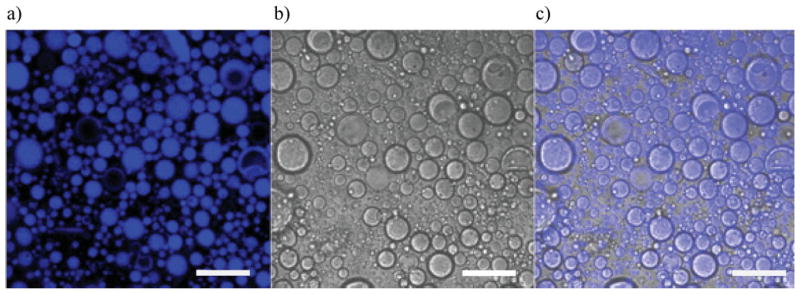

HA–Ge particles were finally crosslinked to an external thiol-modified HA network by crosslinking the free thiol groups on the particle surface to the external thiolated HA network through PEGDA molecules. The fluorescent tag mBBr was used in order to assess the existence of free thiol groups on the surface of particles. Free thiol groups remaining from microgel fabrication on the surface and in the particle are shown in Figure 7. The distribution of free thiol groups in the denser part of the particles is nearly uniform. The hairy region of the particles also includes free thiol groups. This implies that thiol groups of the HA–Ge particles are not fully crosslinked and can still be used for further crosslinking of the hydrogel particles.

Figure 7.

CLSM of the HA–Ge particles stained with mBBr to illuminate the free thiol groups remaining after the fabrication of HA–Ge. a) fluorescent image of the particles, b) bright field image, and c) superimposed image of the bright field and fluorescent pictures. Free thiols are still available on the particles for further crosslinking. The scale bar is 10 μm.

3.2. Composite Hierarchical Hydrogel

The composite hydrogel, shown in Figure 1c, was fabricated and characterized. The HA–Ge particles obtained from the emulsification polymerization process, described earlier, were dispersed in a thiol-modified HA solution. The crosslinker PEGDA was again used to crosslink the thiolated HA molecules and the HA–Ge microparticles. The free thiol groups on the particles crosslinked the particles and the external HA network without the need to modify the particles’ surface.

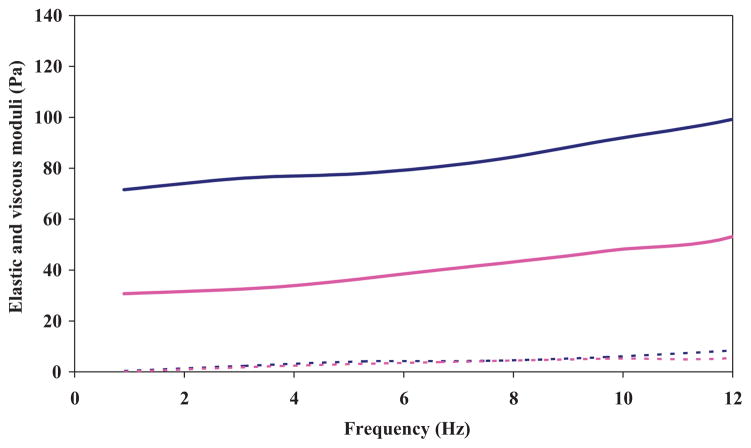

The elastic shear and loss moduli of the composite and bulk gels were obtained using a controlled stress rheometer at room temperature, and are shown in Figure 8. The concentrations of HA and crosslinker in the bulk gel (without particles) and the secondary hydrogel network of the composite (with particles) were deemed equal. The results show that the inclusion of HA–Ge particles into the HA gels leads to an increase in elastic shear modulus, with no significant effect on the loss modulus.

Figure 8.

Shear elastic (G′) and viscous moduli (G″) of bulk HA and HA/Ge composite network. Solid dark blue line: elastic modulus of composite; dashed dark blue line: viscous modulus of composite; solid pink line: elastic modulus of bulk; dashed pink line: bulk viscous modulus.

The mechanical properties of a substrate influence cell growth, adhesion, apoptosis, morphology, and also cytoskeleton formation.[53,54] The Young’s modulus of the substrate should be in the same range as that of human tissue, onto which different kinds of cells are attached, i.e., 1 kPa < E < 100 kPa. Over this range, cell types such as fibroblasts, neurons, myofibroblasts, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells should adhere to the surface and proliferate.

Double network biomaterials, such as HA/Ge composites, are particularly advantageous for tissue engineering applications. They allow injection of the matrix material and retain the cell-specific functionality of the particles. Injectable biomaterials such as bulk gels are required to be very compliant in order to be injectable. Such compliant materials are not suitable for cellular activities. Cells anchored to these structures do not hold a regular shape because of the absence of adequate actin fibers.[53] Previous studies of synthetic materials have shown that anchorage to a substrate with greater rigidity leads to a stronger focal adhesion and a decrease in cell apoptosis.[54] Most importantly, focal adhesion plays a critical rule in mechanotransduction and on the environmental sensing of the cells.[55] Stronger focal adhesion is critical for the tissue engineering of organs such as cartilage and vocal folds. High mechanical stress in the environment should be correctly sensed by the cells in order to lay fibers along the direction of the native organ fibers. The incorporation of rigid microstructures in double network composites promotes cellular activity while keeping the overall stiffness low for better injectability through a syringe.

As a cell adhesion substrate in tissue engineering, the RGD adhesion peptides of HA–Ge particles may facilitate cell adhesion whereas their Young’s modulus of 22 kPa may promote the formation of strong focal adhesion, mechanotransduction, and adequate intracellular cytoskeleton fibers. The low elastic modulus of the overall structure, E ≈ 3G′ < 1 kPa, on the other hand, facilitates injection and delivery of the biomaterial at the point of interest.

Accessibility of the RGD moieties on the surface of the particles in the crosslinked network is possible through proteolytic and non-proteolytic migration mechanisms. Proteolytic migration of cells into the HA matrix occurs through the secretion of hyaluronadaze and other matrix metaloproteases (MMP) by the migrating cells.[56] This mode of migration normally takes place in stiff materials.[56] In the non-proteolytic migration mode, cells migrate through pores in the hydrogel, or they deform the matrix to enter the 3D structure of the hydrogel.[56] In this mode, the elasticity of the hydrogel plays a great role. A recent study has shown that MC3T3-E1 preostoblastic cells are capable of migrating into dense (mesh size of less than 50 nm) but very compliant gels (≈60–100 Pa) through a non-proteolytic (MMP insensitive) mechanism.[57] The low elastic modulus of the external HA network implies the possibility of cell migration through the network to access the HA–Ge particles for cellular adhesion.

The pH-sensitivity of the microgel makes it amenable to drug delivery applications in which a controlled release of growth factors in a precise time-controlled fashion is critical. The present study is ultimately aimed at the repair of tissue damage. Most in vivo tissue engineering processes, including vocal fold tissue repair, involve wound healing.[58] The wound healing process involves a sequence of events triggered by chemical reactions which often change the pH of the wound healing site.[59] The pH-sensitivity of the HA–Ge microgel may be used to alter its swelling ratio, and consequently the drug release rate.

In summary, a Ge and HA structure that is hierarchical and includes hybrid microparticles yields tunable mechanical properties, smart drug release, and cell adhesion properties for tissue engineering applications.

4. Conclusion

Composite particles and networks of HA and Ge were successfully fabricated and characterized. The cell adhesion and signaling properties of the network were greatly improved following the addition of a Ge constituent. Mechanical testing of the composite was performed at two different scales. AFM measurements of the particles’ Young’s modulus yielded a value of 22 kPa, which supports strong focal adhesion in tissue engineering applications. At the macroscopic scale, the elastic and loss moduli of the composite, obtained using a rheometer, were found to be below 100 Pa at low frequency. These results suggest that the composite network combines injectability (a feature of the matrix) with structural integrity of the system and functional microparticles (a cell-specific feature). The pH-responsiveness of the synthesized hydrogel makes it suitable for the smart delivery of growth factors and therapeutics in tissue engineering.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant number DC005788 from the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders, and the Canadian Institute of Health Research grant No. MOP 84495. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Professors Rosaire Mongrain, Hojatollah Vali, Francois Barthelat, David Junker, Subhasis Ghoshal, Maryam Tabrizian, and Dr. Sam Daniel in providing access to their experimental facilities.

References

- 1.Oh JK, Drumright R, Siegwart DJ, Matyjaszewski K. Prog Polym Sci. 2008;33:448. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khademhosseini A, Langer R. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5087. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jha AK, Hule RA, Jiao T, Teller SS, Clifton RJ, Duncan RL, Pochan DJ, Jia X. Macromolecules. 2009;42:537. doi: 10.1021/ma8019442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varga I, Gilányi T, Mészáros R, Filipcsei G, Zrínyi M. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:9071. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharya S, Eckert F, Boyko V, Pich A. Small. 2007;3:650. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu S, Zhang J, Paquet C, Lin Y, Kumacheva E. Adv Funct Mater. 2003;13:468. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim ST, Forbes B, Martin GP, Brown MB. AAPS Pharm Sci Technol. 2001;2:1. doi: 10.1007/BF02830560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JY, Spicer AP. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:581. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yun YH, Goetz DJ, Yellen P, Chen W. Biomaterials. 2004;25:147. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoo HS, Lee EA, Yoon JJ, Park TG. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1925. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan H, Chu CR, Payne KA, Marra KG. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2499. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng Shu X, Liu Y, Palumbo FS, Luo Y, Prestwich GD. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1339. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon SJ, Fang YH, Lim CH, Kim BS, Son HS, Park Y, Sun K. J Biomed Mater Res, Part B: Appl Biomater. 2009;91:163. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amarnath LP, Srinivas A, Ramamurthi A. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1416. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duflo S, Thibeault SL, Li W, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2171. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thibeault SL, Klemuk SA, Chen X, Quinchia Johnson BH. J Voice. 2011;25:249. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turley EA, Noble PW, Bourguignon LYW. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seidlits SK, Drinnan CT, Petersen RR, Shear JB, Suggs LJ, Schmidt CE. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2401. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pavesio A, Renier D, Cassinelli C, Morra M. Med Device Technol. 1997;8:20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khademhosseini A, Suh KY, Yang JM, Eng G, Yeh J, Levenberg S, Langer R. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3583. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zawko SA, Schmidt CE. Lab Chip. 2010;10:379. doi: 10.1039/b917493a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langer R, Tirrell DA. Nature. 2004;428:487. doi: 10.1038/nature02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maskarinec SA, Tirrell DA. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:422. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia X, Kiick KL. Macromol Biosci. 2009;9:140. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200800284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruoslahti E. Ann Rev Cell Develop Biol. 1996;12:697. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eastoe JE. Biochem J. 1955;61:589. doi: 10.1042/bj0610589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shu XZ, Liu Y, Palumbo F, Prestwich GD. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3825. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gil ES, Hudson SM. Prog Polym Sci. 2004;29:1173. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Einerson NJ, Stevens KR, Kao WJ. Biomaterials. 2003;24:509. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ethirajan A, Schoeller K, Musyanovych A, Ziener U, Landfester K. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:2383. doi: 10.1021/bm800377w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Busch S, Schwarz U, Kniep R. Adv Funct Mater. 2003;13:189. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young S, Wong M, Tabata Y, Mikos AG. J Controlled Release. 2005;109:256. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SW, Ogawa T, Tabata Y, Nishimura I. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2004;71:308. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, Smith LA, Hu J, Ma PX. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2252. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kimura Y, Ozeki M, Inamoto T, Tabata Y. Biomaterials. 2003;24:2513. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimura Y, Ozeki M, Inamoto T, Tabata Y. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:603. doi: 10.1089/107632702760240526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuijpers AJ, Engbers GHM, Feijen J, De Smedt SC, Meyvis TKL, Demeester J, Krijgsveld J, Zaat SAJ, Dankert J. Macromolecules. 1999;32:3325. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Z, Ding J. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2008;29:751. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:47. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahmat M, Hubert P. J Phys Chem C. 2010;114:15029. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caldararu H, Timmins GS, Gilbert BC. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 1999;1:5689. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harrington WF, Von Hippel PH. In: Advances in Protein Chemistry. Anfinsen CB Jr, Anson ML, Bailey K, Edsall JT, editors. Vol. 16. Academic Press; New York: 1962. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson TD, Sataloff RT. J Voice. 2004;18:392. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2002.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogawa K, Nakayama A, Kokufuta E. Langmuir. 2003;19:3178. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suslick KS, Price GJ. Ann Rev Mater Sci. 1999;29:295. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banquy X, Suarez F, Argaw A, Rabanel JM, Grutter P, Bouchard JF, Hildgen P, Giasson S. Soft Matter. 2009;5:3984. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hashmi SM, Dufresne ER. Soft Matter. 2009;5:3682. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lekka M, Sainz-Serp D, Kulik AJ, Wandrey C. Langmuir. 2004;20:9968. doi: 10.1021/la048389h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu KK. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2006;39:R189. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt S, Zeiser M, Hellweg T, Duschl C, Fery A, Möhwald H. Adv Funct Mater. 2010;20:3235. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan S, Sherman RL, Ford WT. Langmuir. 2004;20:7015. doi: 10.1021/la049597c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Butt HJ, Cappella B, Kappl M. Surf Sci Rep. 2005;59:1. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yeung T, Georges PC, Flanagan LA, Marg B, Ortiz M, Funaki M, Zahir N, Ming W, Weaver V, Janmey PA. Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton. 2005;60:24. doi: 10.1002/cm.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nemir S, West J. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:2. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Geiger B, Spatz JP, Bershadsky AD. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:21. doi: 10.1038/nrm2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Even-Ram S, Yamada KM. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:524. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ehrbar M, Sala A, Lienemann P, Ranga A, Mosiewicz K, Bittermann A, Rizzi SC, Weber FE, Lutolf MP. Biophys J. 2011;100:284. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.11.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prestwich GD, Shu XZ, Liu Y, Cai S, Walsh JF, Hughes CW, Ahmad S, Kirker KR, Yu B, Orlandi RR, Park AH, Thibeault SL, Duflo S, Smith ME. In: Tissue Engineering; Fisher JP, editor. Vol. 585. Springer; New York: 2007. p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schneider L, Korber A, Grabbe S, Dissemond J. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;298:413. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]